The Social Set

To See and Be Seen

Members of the Gilded Age elite took flight with opulent displays of wealth—and exclusiveness. They dined in Delmonico’s private rooms, sailed on private yachts such as J. P. Morgan’s Corsair, traveled in private rail cars, and danced in ballrooms of private homes or on the dance floors of leading hotels whose ballrooms they reserved for the occasion. A few public locales nonetheless afforded glimpses of Society to those who waited . . . and watched.

Peacock Alley

The promenade at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel drew guests and visitors alike, lured by walls clad in amber marble that glowed in the soft light of etched glass chandeliers. They strolled past stout Corinthian columns and noted the smartly uniformed bellboys who stood like sentinels until summoned to duty. The 980-foot-long corridor was known as “Peacock Alley.” From 1897, when the hotel opened, it quickly became the place to be—and to be seen. Celebrity sightings were frequent. A socialite might pass by or perhaps a titled personage from abroad or a famous stage actress such as Lillian Russell. Mark Twain strolled by in his signature white suit.

Peacock Alley was the result of necessity and serendipity. A late-1880s construction boom in New York gave rise to two hotels in the German Renaissance style, their names synonymous with wealth. William Waldorf Astor financed the Waldorf Hotel that opened in 1893 at the corner of Fifth Avenue and Thirty-Third Street. Four years later, his cousin John Jacob Astor IV countered with the adjacent, equally palatial Hotel Astoria on the southwest corner of Fifth Avenue and Thirty-Fourth Street. Both offered guests the most modern rooms and suites with electricity and private bathrooms, plus room-service dining. When the two hotels were combined as the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in 1897, the connecting corridor from the carriage entrance near the main lobby to the foyer and main restaurant became known as Peacock Alley. The “peacocks” were plenty, remarked one close observer of the social scene, Albert Stevens Crockett, whose Peacocks on Parade provides a bird’s-eye view on the goings-on in the thoroughfare where “ultra-fashionable” names such as “Vanderbilt” or “Astor” might be overheard. With thirteen hundred opulent rooms, the vast and ornate new Waldorf-Astoria was New York’s newest chapter in spatial elegance.

Sadly for the hotel manager, George Boldt, the open expanse of Peacock Alley also attracted gawkers. “Women would sit for hours on the chairs and sofas that lined it, simply staring at those who strolled by, noting frocks and hats and wraps and making comments.” Alas for Mr. Boldt, “to keep the acres of accommodation exclusive proved impossible.” What is more, Peacock Alley became a fashion runway. The flooring was laid with classic mosaic tile, but the red-carpet effect was a siren song. “Any woman who had a new gown of which she was proud found it hard to resist treating herself to the thrill of walking through Peacock Alley.” After all, she could walk where Astors walked, perhaps Mrs. Astor herself.

The Palm Court

A prize locale of the Waldorf Hotel, the Palm Garden (soon dubbed the Palm Court) directly faced the visitor who entered the main entrance by carriage or, more recently, the motor car. The hotel’s open doors “yielded an uninterrupted view of the fashionable who soon became its exclusive patrons.” So wrote on-the-scene scribe Crockett. Arriving as hotel guests, he noted, gentlemen registered, while the ladies made their way to the Palm Court, perhaps for tea after wearying hours of travel. “To stand by the hotel desk with a crowd of men staring was unthinkable.” Late-afternoon tea became a de rigueur ritual at the Palm Court, which for a time rivaled Delmonico’s as “the most-sought dining place in the United States.” But tea time and mealtime soon collided. Observed Crockett, “It was not long before people who came for tea began to throng the doorway before waiters had cleared the luncheon tables.” Quite simply, “everybody wanted to get into it.”

One notable attraction at the Palm Court, peculiar as it sounds today, was a troupe of Tyrolean dancers—three women and three men—who wore Alpine costumes, yodeled, and danced. Said Crockett, “To most Americans, yodelers were novelties, and those Swiss warblers proved a drawing card.” The Palm Court soon became a “lodestone” from the Alps and temporarily “raided” Delmonico’s clientele.

The Palm Court was also the setting for the legendary Bradley Martin Ball in February 1897. The Four Hundred were in attendance, the names from old and newer New York: Astor, Van Cortlandt, Van Alen, Livingston, et al. A two-hour cotillion was followed by “supper” served at one a.m. in the café and in the Palm Court, which was decorated with “huge vases of American Beauty roses.” Mrs. Astor attended the ball, and perhaps she dined after midnight in the Waldorf-Astoria Palm Court.

Theater and Opera

In Gilded Age Society, an evening at the theater or the opera satisfied not merely a yearning for music or the dramatic arts. Much more was at stake than a desire to hear the famed “golden voice” of Sarah Bernhardt starring in Adrienne Lecouvreur at Booth’s Theater or the diva Adelina Patti in Rigoletto at the Metropolitan Opera. The choice was not between the soliloquy or the aria but which evening might advance or sustain one’s social position. “There is no more popular or agreeable way of entertaining people,” wrote Emily Post, than to “dine and go to the play.”

The theater district grew along Broadway and Sixth Avenue between Union and Madison Squares in the vicinity of Ladies’ Mile. Playhouses and retail palaces mixed to the benefit of both. Before the Civil War, touring stock companies played in theaters nearer to the Bowery, offering romantic melodramas and period plays. Famous actors often owned or managed those theaters (as did Elsie De Wolfe before she became a prominent interior designer for the Four Hundred). The postwar theaters, such as the Bijou, the Abbey, and the Casino (noted for its roof garden and Moorish features) rented their spaces for lengthy runs, with Shakespeare in high demand. In 1885, the Lyceum Theater was the first playhouse to be lighted by electricity (installed personally by Edison), and the electrification of Broadway street lighting transformed the area into the “Great White Way.”

Traveling troupes presented new plays weekly in outlying cities, but hosts in Gotham faced the choice between a long-running hit or an untried new play that might prove “dull.” It was understood that the hosts would buy the tickets, provide dinner at their home or a restaurant, and arrange the transportation.

Hosting a theater party was especially attractive to the family whose daughter had recently made her début and was preparing to “take her place beside her mother as hostess.” She might now give a late-afternoon tea under the auspices of her parents or oversee a theater party with a “charming . . . little dinner” at the family home, followed by the play and a return to the home, where “a supper is served, and the carriages of the guests await them at their hostess’ door.” One etiquette guide suggested hiring a horse-drawn “omnibus” for the group, a “glorified vehicle, low-slung, easy-rolling, resplendent with paint, shellac, and plush.” Ladies were to wear dinner dresses, gentlemen dinner coats (“often called a Tuxedo”).

It was important to secure the best seats, though “New Yorkers of the highest fashion almost never occupy a box at the theater,” as Emily Post remarked in Etiquette. Seating in the theater followed the customary gentlemanly stewardship of the lady. He holds the tickets, gives them to the usher, escorts the lady down the aisle, lets her precede him to their seats. (“In passing across people who are seated, always face the stage and press as close to the backs of the seats as you can.”) Also, “a lady never sits in the aisle seat if she is with a gentleman.” A young woman unaccompanied required a “chaperon,” lest she risk “sharp criticism from alien tongues,” according to The Well-Bred Girl in Society.

The Lyceum was the favored theater of the Four Hundred, who flocked to drawing-room dramas such as Young Mrs. Winthrop (1882) and One of Our Girls (1885) in their formal evening attire. Certain common irritants, however, were on record. Women’s chapeaux blocked the views of patrons seated behind les femmes’ extravaganzas of ribbons, feathers, and flowers. And the custom of conspicuously “handling boxes of confections between members of a theater party” was maddening. So were “theater pests” who were wont to leave their seats after every act and return when the curtain had once again risen, annoying all who were obliged to rise and let them pass. Consideration for others, in addition, meant no whispering, talking, or rattling programs. Persons attending a performance should “express their appreciation and satisfaction by proper applause,” stated American Etiquette. Those who might leave the hall while the performance is in progress are “offensive.” “Common politeness to the performers, a courteous regard for the rights of the audience, the common instincts of civility, all demand that this offense shall be avoided.”

Early departures and late arrivals, however, were de rigueur at the opera, unlike those music lovers who arrived on time, took their seats in the first-floor rows, and applauded a new soprano or tenor through waves of curtain calls.

Society attended the opera for social reasons of its own. In the opening scene of Edith Wharton’s best-selling novel The Age of Innocence, set in the 1870s, a wealthy young bachelor with Old New York bloodlines, arrives at the Academy of Music downtown on Fourteenth Street after the performance of Faust has begun because it was “not the thing” to arrive early. Within moments of entering his family’s private box, he leans his chair against the back wall and scans the occupants of another box across the hall to spot (and appraise) his fiancée before turning his attention to the opera. Wharton remarks that the “shabby red and gold boxes of the sociable old Academy”—which boasted the US premieres of Aida (1873) and Carmen (1878)—were cherished by Knickerbocker New York for superb acoustics and for “keeping out the ‘new people’ whom New York was beginning to dread and yet be drawn to.” The scarce boxes at the Academy were said to be as hotly sought as seats on the New York Stock Exchange.

The “new people,” wrote Wharton, would not be denied their own luxurious theater experience. Not to be stymied by New York’s Old Guard, William H. Vanderbilt rallied his newly rich compatriots, including his sons William Kissam and Cornelius H., together with William Rockefeller, J. P. Morgan, Jay Gould, William C. Whitney, and George Baker, as well as older patricians such as William Rhinelander and Ogden Goelet, to establish “a new Opera House which should compete in costliness and splendour with those of the great European capitals.” The Metropolitan Opera House began to rise at Broadway and Thirty-Ninth Street with seating for over thirty-six hundred people upon completion and featuring the “Golden Horse-shoe” of seventy luxurious boxes for the wealthy. Mrs. Astor claimed Parterre Box Number 7. From the inaugural performance of Faust on October 22, 1883, the new opera house was an immediate success, dooming the Academy. The net worth of those who attended the premiere was estimated at $540 million ($14.1 billion today). Or, as one newspaper put it, “the Goulds and Vanderbilts and people of that ilk perfumed the air with the odor of crisp greenbacks.”

In New York Society on Parade, Ralph Pulitzer, like Edith Wharton before him, captured the social drama unfolding in the private boxes of the new Metropolitan Opera House. The orchestra seats and galleries fill as the orchestra tuned, he wrote, but Society filtered into its grand-tier boxes only when the performance had been under way for upward of an hour. “When the party reaches the top of the stairs a liveried usher shows them to the door of their box, which he unlocks and opens for them. On this door is the name of their host.” Then a “maid hastens to help the ladies off with their opera cloaks and fur overshoes,” while the men “dispose of their own hats and coats in odd corners of the room.” Only then does “the hostess, pulling aside the curtain, . . . sweep down to the front of the box and indicate to the other ladies which of the front seats they are to adorn.” Society does not arrive quietly: “There is a stir and rustle behind the velvet curtain at the back of one of the notable grand-tier boxes. The curtain rattles aside, down to the front of the box sweeps a radiance of satin, a scintillation of diamonds, a lustre of pearls, a glow of rubies. . . . Society has reached the opera.”

Five to seven persons occupy the box, three or four men behind, two or three ladies at the front. Among themselves, host and guests raise “a battery” of opera glasses to their eyes to see who’s who around the Golden Horse-shoe. Pulitzer remarked that if bored by the music, “Society has opportunities for scrutinizing its clothes, its jewels,” and its own cohort from the recent dinners and balls of the current season. Gossip and intrigue stir, and box-to-box visiting between acts raises the pulse. “The box parties go because the opera is fashionable; the opera is fashionable because the box parties go.”

The primary purpose of the private box at the opera, Pulitzer concluded, is to man the front line in a class war. Exhibiting its exclusivity, Society “shows itself in the midst of those whom it is rejecting,” the vulgar “horde” in the seats below (or ready to devour the morning-after newspaper accounts of those among the Four Hundred who were seen at the previous evening’s performance). Pulitzer’s account of “New York Society on parade” is a self-conscious spectacle intended “to tantalize the vulgar into poignant envy” and impress on them their own exclusion.

The opera itself, noted Pulitzer, is nearly incidental. The singers, he wrote, were valued solely by price, for Society “prefers song which is so expensive that it must be the best. They prefer to trust the impresario’s purse rather than their own ears as the criterion of art.” Pulitzer, however, raised his opera glass to his eyes to see in the orchestra seats below a few familiar “fellow-members of Society.” Easily able to afford boxes of their own or accept invitations to others’ boxes, they “prefer to sit . . . in the rows,” for these men and women come “from sheer desire for music, to let the world in which they work and worry drift from their sight, and for a little while live in that land of visions to which the thrill and thralldom of the music alone can lift them.”

Stage-Door Johnny

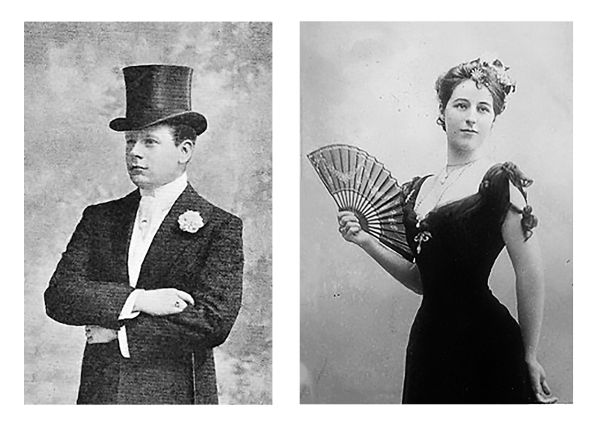

The 1905 divorce of Mr. and Mrs. Edwin Main Post of New York City was hardly newsworthy. More momentous events of the year included the launch of President Theodore Roosevelt’s first full term in office and the record-breaking flight of Wilbur Wright’s Wright Flyer III, which exceeded thirty minutes in the air. Even the end of the thirteen-year marriage of a rather prominent New York couple failed to qualify for “Page One” of the New York Herald or Tribune. Only later would Mrs. Post, the divorcée, become famous as the author of Etiquette, a go-to bible for unimpeachable cradle-to-grave manners. But if her fame lay ahead, Mrs. Post’s split was nonetheless instructive for the light it shone on the demimonde of Gilded Age New York, for Emily Price Post had initiated divorce proceedings upon learning of her husband’s chronic affairs with chorus girls and young actresses. His infidelities marked him as a “stage-door Johnny.”

Such a man hovered at the theater stage door to attract the attention of a young actress or chorine as she exited after the show. He cut a fine figure in a silk high hat with a yellow chrysanthemum boutonniere, a walking stick in one hand and a bouquet in another. “He met his chorus girl as she stepped over the threshold, presented his bouquet, and whisked her away in a hansom cab.” Perhaps he greeted his “lady of the chorus” with a diamond brooch or tucked a necklace of the gems in her bouquet as a sweet surprise. Low-paid dancers and bit-part actresses were easy pickings, barely scraping by in run-down boarding houses, subsisting on meager diets. The novelist and journalist Theodore Dreiser spotlighted such a young woman in his 1900 novel Sister Carrie, as the chorus girl Carrie Meeber struggles on the lower rungs of the show-business ladder, where a manager “judged women as another would horseflesh.” (A famous twentieth-century Thoroughbred race horse was named Stage Door Johnny.) As her star rises, a young male escort takes her to dinner at Delmonico’s, while “gentlemen with fortunes” send “mash” notes professing their adulation and longing for her company. Flocks of such single “girls” clustered in New York from the late 1800s, some from immigrants’ families, some lured to the city from America’s farms and hamlets.

The man’s wee-hours after-theater entertainment would cost him, at minimum, a champagne supper for two at a lobster palace or steakhouse or a restaurant featuring duck à l’orange. In Peacocks on Parade, Albert Stevens Crockett describes how the pair might go for a “spin” through Central Park in order to time her entrance at dinner: “She waited until the after-theater supper crowd had gathered, and then, on the arm of her gallant, paraded across the dance floor. The orchestra leader, if he played his part well, was watching for her, and she was greeted by the strains of the hit song from her show. She pretended to be a bit flustered by the attention. . . . But she made her way, with the majesty she had been taught, to her table, gathered in her train, . . . and sat down with her completely happy escort for a ‘bottle and a bird.’ . . . It was enough that she had the spotlight.” George Sala, the British journalist visiting New York in 1879–80, noted the extravagant “champagne suppers” given to “blonde belles of the ‘Black Crook’ burlesque.” Perhaps such an ingénue harbored hope that her rich admirer might lead her to the altar. If not marriage, the next best thing for a young woman with dimming prospects in show business could be life as a rich man’s cherie.

Gilded Age mistresses were, if not a commonplace, a persistent perquisite of elite male entitlement. Discretion was advised. Rumors flew about the escapades on Mrs. Astor’s husband’s yacht, Nourmahal (translation: “Light of the Palace”), but Mrs. Astor fairly boasted that mal de mer, seasickness, kept her from ever once setting foot on the vessel. Failure to respect this unspoken boundary might lead to embarrassing circumstances. The widower James Van Alen brought one fetching young woman ashore for a weekend at Newport, instantly rousing the “concerted hostility” of “all the Queens” who took her measure and immediately voiced their objections. The “NOT acceptable” lass was dispatched within hours, and Mr. Van Alen saved face by claiming “the sea air did not agree with her.” No harm done.

A very different outcome awaited the oilman Edward (“Ned”) Stokes, whose place in history was secured by the fatal bullets he fired into “Jubilee Jim” Fisk, the rich and notorious Wall Street speculator in January 6, 1872. Married to the wealthy Maria Southack a decade earlier, Stokes owned a steam yacht on which he gave “many parties,” some “stag,” others that included “ladies of easy virtue.” Crockett warned that it was not a business disagreement but Stokes’s failure to keep his mistress (and reputed “Broadway gold-digger”), Josie Mansfield, his chère amie, in “discreet seclusion,” inadvertently setting the stage for a flirtation between “handsome, dare-devil” Jim Fisk, himself a flagrant stage-door Johnny. In a jealous, murderous rage, Stokes “trailed” Fisk to the Grand Central Hotel and “pulled his gun,” mortally wounding Jubilee Jim. (After being convicted of manslaughter and serving time in Sing Sing, Stokes later found redemption of a sort as the hotelier of the prestigious Hoffman House.)

When the temperance movement and new liquor laws in the 1910s slowed the flowing champagne of the lobster palaces to a trickle and fatally pinched the profits, the era of the stage-door Johnny was nearing its finale. In its heyday and for that moment in time, however, the chorus girl was a star, and stage-door Johnny was more than happy to be her impresario.

Central Park

Mrs. Astor’s dinner guests, sipping their course of Consommé Marie Stuart, might have barely glanced up to notice her richly framed landscapes that lined the ballroom walls. Her guests collected such art themselves, paintings that typically featured “a lake or river,” “a wild woodland or teeming garden,” “a bosky nook,” a “smiling valley,” or a “boundless vista”—exact words that Henry James used to describe the parkland that lined Fifth Avenue mansions, including Mrs. Astor’s own French Renaissance home. The Four Hundred guests would have known that “boundless vista” well. In a manner of speaking, they lived inside the animated landscape that was Central Park.

Few of the Gilded Age Four Hundred were mindful of the fierce politics that underlay the development of Central Park. For them, the 843 acres of woods and meadows in the middle of Manhattan provided the setting for lifelong pleasures. Edith Wharton, in her novel The Age of Innocence, allowed her fictional young gentleman to persuade his fiancée “to escape for a walk in the park.” The heiress Elizabeth Drexel and her sisters “were allowed to drive to Central Park with their governess,” and Daisy Hurst (later Harriman) was one of “the decorous little girls who walked with their aunt, or governess, in Central Park” in the 1880s. In winter, Daisy and her sister ice-skated on the frozen park pond, where a boy was memorable for doing “figure eights.” As ladies, both women thrilled to sleighing in the park. Miss Drexel recalled the “keen frost” that “coloured the women’s cheeks” and “brightened their eyes” as they “sat back wrapped in their luxurious fur rugs watching the occupants of the other sleighs.” Mrs. Vanderbilt, she remembered, “would flash by in a blaze of red, . . . dark red liveries, red carriage work, . . . carved gold bells on the horses.”

Springtime brought another pleasure. Daisy Harriman recalled the “thrilling and colorful event,” the “annual meet of the New York Coaching Club” held on the first Saturday in May. “About fifteen drags usually assembled at the Brunswick Hotel in Twenty-sixth Street,” she remembered, “and drove up to and around Central Park, and back in time for dinner at the hotel. The prettiest women in town, in crisp summer gowns and leghorn hats, with bouquets of cornflowers, daisies or buttercups, flowers to match the racing colors of the host, sat atop the coaches. The men wore the Coaching Club uniforms, green coats with gray top hats, and boutonnieres. Even the horses were dressed, with flower rosettes behind their ears.” With the men wearing the club’s “livery of black coats, check suits, and buckskin gloves,” the ladies in their “voluminous trailing skirts,” one could well observe, as Joseph Pulitzer’s 1881 World editorial put it bluntly, “There is the aristocracy of Central Park.”

By the 1890s, however, a “walk in Central Park” was also promoted as a site of health and recreation by such excursion guides as Sight See-ers in the Metropolis. The out-of-town excursionists, like the hoi polloi who lived and worked elsewhere in the city, were fully entitled to enjoy Central Park, which was promoted by city fathers as the healthful “lungs of the city.”

Central Park had first opened to the public in the winter of 1858, even as park construction continued. The park, like most public works projects, had been the subject of decades of political infighting over issues of location, construction, and cost. Prior to the Civil War, Old New York family names, among them the propark advocate William Backhouse Astor Sr., Mrs. Astor’s future father-in-law, had advocated the virtues of a park equal to London’s Hyde Park or Paris’s Bois de Boulogne. The parallels were self-evident for socially ambitious New Yorkers, and the promise of rising real estate values in the designated parkland proved irresistible. New York’s brokers, bankers, merchants, and lawyers gathered in support, one of their petitions promising that Central Park “would constitute one of the largest . . . parks in the world; and one which alone would be worthy of the future greatness of the city.” A city commission issued its Central Park report in fall 1855, authorizing construction plans.

The blueprint for a large public park traces back to Andrew Jackson Downing (1815–1852), the American dean of “landscape gardening,” the term he used in 1841 in his influential Treatise. His mandate: “Plant spacious parks in your cities, and loose their gates as wide as the morning, to the whole people.” A younger associate of Downing, Calvert Vaux (1824–1895), an Englishman, absorbed his mentor’s ideas on horticulture and rural values as he gained extensive architectural experience in the US. For a design competition for Central Park, Vaux partnered with Frederick Law Olmsted (1822–1903), a journalist who had traveled throughout the US South and far West, reflecting in his writings on the various topographical features and their impact on human life.

Heir to the poetic tradition of Romanticism, Olmsted believed that a landscape could be morally uplifting, that its inherent message of grace and repose with a hint of mystery could buoy the spirit and elevate the individual. The park would thus be the antidote to the toxic noise, congestion, crime, vice, and frantic pace of the city. (The same aesthetic ideal governed the landscape tradition in art, from the eighteenth-century painter Thomas Gainsborough through such contemporary English painters as John Constable and J. M. W. Turner. The paintings distilled the values of the landscape, and the landscape, in turn, exhibited the physical features that were prominent in the paintings.)

In 1858, Olmsted and Vaux won the competition with a “Greensward Plan,” featuring acres of turf and growing grasses to be punctuated with numerous pathways, thirty-six distinct bridges of granite or cast iron, a Ramble, a castle, a Mall with corridors of elms, a “Bethesda Terrace” and “Bethesda Fountain,” a lake, bridal paths, a meadow where sheep grazed, and a lily pond where children sketched and small boys sailed model yachts. The area extended from Fifty-Ninth to 106th Streets, and the cost for the necessary parcels of land alone ran to $5 million ($133 million today).

The land intended for the park was by no means vacant at the outset. The park’s first engineer, Egbert Viele, recalled the park land as “the refuge of about five thousand squatters, dwelling in rude huts of their own construction, and living off the refuse of the city.” Principally of “foreign birth,” this population had “very little knowledge of the English language,” he wrote, and “very little respect for the law.” He compared them to ancient Gauls: “They wanted land to live on, and they took it.”

The press rallied in 1856 to condemn the dwellings and businesses in the park land—and the occupants too. A New York Times dispatch of March described Irish families in the area dwelling in “rickety . . . little one storie shanties . . . inhabited by four or five persons, not including the pig and the goats.” The Journal of Commerce censured those who were “in the habit of cutting small limbs from the few remaining trees” for use in drying hops to brew beer. The Evening Post cautioned that the park was currently a “scene of plunder and depredations,” the “headquarters of scoundrels of every description,” and the site of “gambling dens, the lowest type of drinking houses, and houses of every species of rascality.” On the western side of the park land, in addition, were the “nuisance” industries such as leather dressing and bone boiling that produced foul odors. Seldom mentioned was the sizable population of African Americans who also made their homes in the vicinity, some of them property owners. Nor did the press comment on the trades in which a high percentage of the “pre-parkites” (as one commentator termed them) were employed—as tailors, carpenters, masons, gardeners, domestics, laborers. The eviction of this entire population was authorized by a commission report of 1855. The city inspector ordered “the removal of piggeries and other nuisances now existing on the Central Park grounds.” In later decades, the practice would be known by the term “slum clearance.”

Work on park construction began in earnest in 1858, and for two decades, Central Park was a construction site before it became a park. During the years of a depression, jobless workers flocked for employment clearing foliage and the “rubbish” of demolished structures as the park land took on the appearance of a military campaign. Park dwellers had cut trees for firewood, but more than 150,000 shrubs and saplings needed removal, many thorny or overrun with poison ivy. The Times described gangs of workers “removing the bushes that grow rank and worthless in the vicinity of the odoriferous swamps.” Bogs were drained, lest “pestilential . . . rank vegetation and miasmatic odors taint every breath of air.” There were blasting teams, road-building crews, masons, blacksmiths, carpenters, stone carvers and stone breakers (these last earning nine cents per cubic yard). Olmsted assigned the men he judged “best fitted for hard work” to the task of sledgehammering rocks. Huge boulders were blasted from the ground, and crews of derrick workers loaded them onto two-horse trucks with cranes. There were wagon teams and wheelbarrow gangs and workers who manned carts. The work went on. In 1859–60, with construction at its peak, the city was the largest New York employer, with an average of four thousand workers on the payroll. The lawyer and diarist George Templeton Strong concluded that “Celts, caravans of dirt carts, derricks and steam engines are the elements out of which our future Pleasance is rapidly developing.”

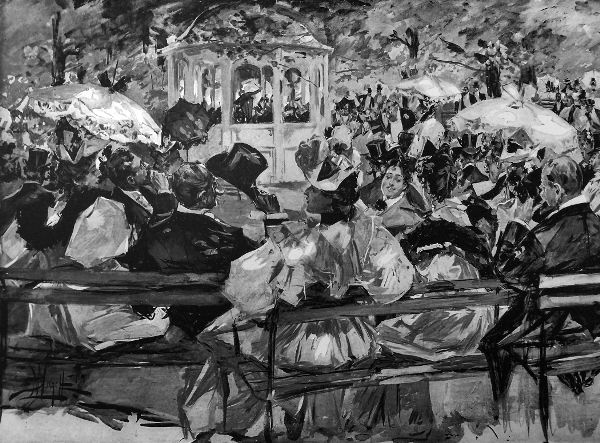

Construction was completed by the early 1870s, and the park immediately beckoned hundreds of New Yorkers. Henry James viewed the challenge as “a crushing mission . . . laid upon . . . this limited territory” but one “which has risen to the occasion.” He was, he pronounced, “thrilled at every turn.” On Sundays, the park was a pleasure ground for working-class New Yorkers who could muster the five-cent fare to ride the El, the elevated commuter train that took them to the park on their sole weekly day of leisure. Sunday-afternoon concerts that began in 1884 drew large numbers, and one young woman pronounced Central Park to be “quite as good as going to Coney Island,” for the carousel and goat rides were favorites. By the turn of the century, the “common man and the common woman” and “common child” were everywhere on the park paths in early summer, according to Henry James, who enjoyed seeing small boys sailing model boats on the pond and “little girls . . . frisking about on the greenswards” in “exquisite attire” with “beribboned hair.” A self-confessed “brooding analyst,” James was cheered by the sight and heartened by its promise for the country’s future. The 1890s saw “new women” bicyclists on the pathways.

For the Four Hundred, Central Park was their playground, an equestrian right and privilege. Wintertime sleighing was a must, the family coachmen at the reins. On midwinter afternoons, Elizabeth Drexel recalled, “the air was full of the tinkle of sleigh bells,” and “the snow churned up by the beat of the hooves fell in a glittering spray as the sleighs passed and repassed each other in Central Park.” She remembered that sleigh harnesses were “so gaily decorated that they began to look like the trappings of mediaeval chivalry.”

For the equestrian, “Nothing is more conducive to pleasure of a rational character than the ride on horseback upon every pleasant day,” extolled Manners, Culture and Dress, but the etiquette of riding and driving was “exact and important.” Yet the schooling of the rider must take place out of sight—certainly not on the bridle paths of Central Park! “A novice makes an exhibition of himself, and brings ridicule to his friends.” For those who did have the benefit of a groom, Manners offered detailed instructions. “In riding with the ladies, it is your duty to see them in their saddles before you mount.” The lady was to stand “on the near side of the horse,” with “her skirt gathered up in her left hand, her right hand on the pommel, her face towards the horse’s head.” The gentleman was cautioned that to assist her into the saddle, he must not boost the lady with such “vaulting ambition” that “she loses her balance and falls to the other side.” Daisy Hurst road sidesaddle according to the fashion for women and recalled that when riding, one’s back must be ramrod straight. One socialite, Mrs. August Belmont, alternated between using two saddles, one for the right and one for the left of the horse, “to prevent any distortion of the figure caused by always riding on one side.”

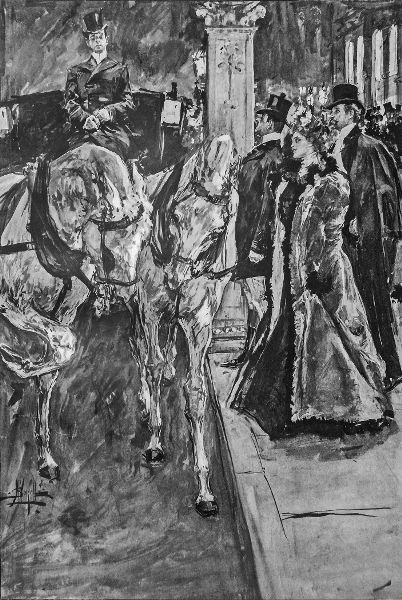

Figure 42. Carriages on Central Park pathways

Despite the pleasance of Central Park, at times it was beset by “tramps” and “other unpleasant people,” including young ruffians, and the Four Hundred were not immune to their mischief. In March 1900, the New York Times reported that “all manner of charges have been made . . . against small boys who gather during the hours when the bridle paths are most frequently used.” “The boys gather on the bridges overlooking the bridle paths and throw stones at the riders,” the report explained, “or make such a clatter with their roller skates that spirited horses are frightened and sometimes run away.” In one case, Miss Lucy Otterson, “a daily rider on the bridle paths,” was “thrown and injured when her frightened horse ran away.” No police were on hand. “Some friends of Miss Otterson saw her predicament and drove her home in their carriage.” The whereabouts of her horse were not made known in the newspaper.

Club Life

According to the chronicler Francis Gerry Fairfield’s The Clubs of New York (1873), to the New York gentleman, his private club might be considered his “home.” In any of the numerous clubs that dotted lower Manhattan and later relocated, according to fashion, to the Upper East Side, one could expect to find a “large handsome morning-room with sofas and chairs,” dressing and bathrooms, a library with “rare and interesting books,” the leading newspapers, and a “writing-room” with little tables, notepaper, and envelopes. Serving breakfast and dinner, certain clubs’ dining rooms were prized for their wine cellars and “elegant epicureanism” (especially the Union League Club). Ralph Pulitzer, a club-life insider, noted that the younger men of Wall Street or the city’s law offices—that is, the bachelors—relied on their clubs for a game of squash after work, followed by a bath and formal dress for dinner. The “advantage,” said Pulitzer, is that “wedlock” has not forced these young men to dress at home. It allows them, once in evening attire, to “sit at ease” with the “ardent mellowness of successive cocktails.” Should gentlemen dine at the club, postprandial sojourns to its “well-ventilated smoking-room” guaranteed “after-dinner stories and cigars of the finest brands.” The clubmen, Henry James observed, enjoyed “lounging, gossiping, smoking, newspaper-reading, bridge-playing,” and “cocktail-imbibing.”

Like other men of substance, numerous gentlemen of the Four Hundred were in three or four of the New York clubs, including at least one that was known to be exclusive. “A man to be eligible for membership in such a club,” advised Emily Post, “must not only be completely a gentleman, but he must have friends among the members who like him enough to be willing to propose him and second him and write letters for him; and furthermore he must be disliked by no one—at least not sufficiently for any member to object seriously to his company.”

With a touch of the tribal, clubs signaled family pedigrees, political bonds, or pursuits of leisure. The august Union Club, a bastion of Old New York, predated the Civil War and boasted a membership gleaming with “names of Knickerbocker fame,” the Dutch “Vans” including Van Cortlandt, Vandervoort, and Van Rensselaer. The New York Yacht Club welcomed Mrs. Astor’s yachtsman husband, William Backhouse Astor, while aficionados of racing, notably August Belmont, formed the American Jockey Club. Gentlemen of a literary bent gathered at the Century Club, as Edith Wharton noted, with its circle of “the fellows who wrote,” the “musicians and the painters.”

Clubs also measured status and power—and could roil with rivalry inside and out. In the Union Club, “old magnates of New York Society” locked horns with “the new Napoleons of wealth by trade.” Their conflict “agitated the club” and “occasionally threatened to render it asunder.” (Convinced that standards for membership were falling, a breakaway group formed the Knickerbocker Club in 1871.) The Manhattan Club, founded over dinners at Delmonico’s in 1865, mounted a frontal assault on the political power of the Union and Union League Clubs, its charter members a who’s who of the Gilded Age stock market and railroad wars: Cornelius and William K. Vanderbilt, Daniel Drew, and Jay Gould. According to The Clubs of New York, the Manhattan Club was the “spider” that “spins its gossamer webs of policy, and manages the details of campaigns” while keeping itself “silent within the mahogany doors of its splendid Fifth Avenue den.”

Though suspicions arose that the clubs were centers of “extravagance and temptation,” social norms were strictly upheld. Gambling was forbidden. (“As long as men are within the walls of their club they must conduct themselves as gentlemen.”)

Frank Crowninshield’s Manners for the Metropolis set the tone. One was to avoid “long or prolix discussions,” he advised a new member or guest, lest you be labeled “vulgar.” Instead, Crowninshield urged the “simple and conventional” conversation at a club that consists of the following:

- “Hello!”

- “Deuced cold!”

- “Have a drink?”

- “Who has a cigar?”

- “How about one rubber?”

The “safest and most refined remark in constant use,” he insisted, is “Waiter, take the orders,” syllables that can be dispensed with if one simply rings the bell.

Nevertheless, throughout the Gilded Age, many ladies feared that all-male clubs were dens of iniquity calculated to “lead their sons and husbands astray.” Warned Social Etiquette of New York, “Club life among gentlemen tends more and more to postpone marriage.” Eligible bachelors, it was feared, were too well satisfied with club life to lead a bride down the aisle. (Meanwhile, the “nervous wives and mothers” remained willfully oblivious of the escapades on the offshore anchored yachts, such as William Astor’s Nourmahal, or the frolics in the midtown lobster palaces awash in champagne in the wee hours.)

Excluded by the strictures of sex and gender, the ladies of the Four Hundred eventually formed their own association. Championed by Daisy Harriman and her friends, the Colony Club was established in 1904, its residential clubhouse on Madison Avenue between East Thirtieth and Thirty-First Streets designed by Stanford White and completed in 1908.

Newport

“The Nation’s Social Capital” or “Catastrophe”—the bouquets and brickbats flew during the Gilded Age as the onetime sleepy Rhode Island village known as Aquidneck Island became, as of the 1880s, the annual summer headquarters of the Four Hundred. Blue bloods of the South and New England had long gravitated to Newport for the summer season. Soon it was to be the playground of the richest of New York’s rich.

The newcomers might be flush from a recent windfall in metals, mining, or manufacturing. Fashionably attired, the wives could be seen shopping along Bellevue Avenue, where “branches of leading London, Paris, and New York firms were established every summer,” purveying “rare goods” for “personal wear, the decorations of houses, horses, and humans.” The short summer season was deeded to Society for luncheons, dinners, balls, open-air driving, private beach bathing, yachting, strolling, and games. Throughout July and August, a swirl of social competitions featured the latest in fashion, jewels, horseflesh, retinues of servants, cuisine by legendary French chefs, and trophy guests from the royal houses of Europe and England.

The grandest competition, it was understood, was architectural. No longer would a shingled or clapboard dwelling whose rustic charm attracted generations of summer residents longing for the simple pleasures of sun and sea suffice. The vacation “cottage” now denoted grand seafront mansions designed by celebrity architects such as Richard Morris Hunt and Charles McKim—with names such as “Marble House,” “Belcourt,” “Ochre Court,” “The Elms,” and “The Breakers”—and the owners were “cottagers.”

Mrs. Astor, not surprisingly, was pivotal to the success of the new Newport colony. She staked her inimitable claim once her closest adviser, Ward McAllister, spoke persuasively of the rewarding summertime weeks in a sheltered Rhode Island conclave with her social set. In 1881, Mrs. Astor purchased “the old Barada place on Bellevue Avenue” and chose Richard Morris Hunt and the firm of McKim, Mead, and White to undertake the extensive renovations for her summer palace, “Beechwood.” She quickly entered into the spirit. “Mrs. Astor entertained in a royal manner,” recalled Maud Howe Elliott (b. 1854) whose Boston family had summered in Newport for generations. She added, “The newspapers of the day blazoned the fact that ‘Mrs. Astor served her dinner on her gold service and wore her string of pearls—the finest outside that in the Louvre.’” In her memoir, This Was My Newport, Elliott (a Pulitzer Prize winner and daughter of Julia Ward Howe, who wrote “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”) decried the annual “New York invasion,” the “invading tribes” who overran the onetime “dainty isle.” “Whole families of social prominence took us by storm,” she exclaimed. And “still they come!” Her dismay was echoed by the novelist and Boston native Henry James, who cherished the Newport of his boyhood. During a visit in the 1904 summer season, he waxed nostalgic about the long-gone “Arcadian summer-haunted valleys, with the sea just over some stony shoulder.” He missed the “sandy coves” of a pristine old Newport that was “so beautiful, so solitary and so ‘sympathetic.’”

Figure 46. Entrance to “Ochre Court,” summer residence of Mrs. Ogden Goelet

No more. The “whirligig of time” had landed James in a transformed summer resort. “It now bristles with the villas and palaces” that are “monuments of pecuniary power,” he wrote. The mansion cottages were “grotesque,” and he called them by the common term for useless, costly things that burden their owners: “white elephants.” Pachyderms aside, the “social revolution” that James saw was a fact. The invasion that Maud Elliott lamented had succeeded. Newport was conquered.

For the Gilded Age Four Hundred, the Newport season was mandatory. Ward McAllister suggested that Newport was “the place . . . to take social root in.” Elizabeth Lehr was frank: “So much prestige was attached to spending July and August at the most exclusive resort in America that to have neglected to do so would have exposed a definite gap in one’s social armour.” The armor reflected an impeccable pedigree, irreproachable comportment, and wealth. The “gap” was to be avoided at all costs. Each rival hostess, the queen of her palace, jealously guarded her guest lists, the armament of social power. Mrs. Lehr recalled that the six or seven summer weeks were “crowded with balls, dinners, parties of every description, each striving to eclipse the other in magnificence.” In “the spirit of rivalry . . . colossal sums were spent.”

Figure 47. “The Breakers,” summer residence of Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt

If elegance was the watchword, novelty was the stimulant. Elizabeth Lehr hinted at the tedium: “Another season, the same background of dinners and balls, the same splendours. The same set, the same faces.” Added May Van Rensselaer, “The restlessness of the summer colony is well known. All amusements pall after a couple of seasons.” In a kind of entertainment arms race, at “Rosecliffe,” one summer, two hundred dinner guests of Mrs. Hermann Oelrichs were treated to a performance by the Russian Ballet, imported from the city for the occasion. At William K. Vanderbilt’s cottage, “Marble House,” the Visiting Duke of Marlborough (spouse of the former Consuelo Vanderbilt, now the Duchess of Marlborough) found the indoor fountain surrounded by three hundred live hummingbirds. One especially memorable ball prompted McAllister to record the “brilliant effect” of “two grottos of immense blocks of ice” with a “jet of light thrown through each of them, causing the ice to resemble the prisms of an illuminated cavern, and fairly to dazzle one with their coloring.” As the ice blocks melted, McAllister continued, the effect was a “charming glacier-like confusion, giving you winter in the lap of summer.” “All Newport,” McAllister concluded, “was present to give brilliancy to the scene.”

Nevertheless, some social events recalled past times on old Aquidneck Isle, such as setting out by rowboat for lunch on Gooseberry Island or a primitive feast at the exclusive Clambake Club, “where elegant women . . . took off their long kid gloves to eat the clams cooked in the same stones the Indians had used.” The rustic past was accented at “Bayside,” where McAllister “animated” the scene for his trademark afternoon champagne picnics. Quaffing champagne, squinting at the far pasture, guests glimpsed a flock of grazing sheep and a small herd of cows, all stage props returned to the farmer the following day. “It would never do,” he explained, “to have a gathering of the brightest and cleverest people in the country at my place with the pastures empty.”

The “little parties” at Newport, McAllister advised, were “stepping-stones to our best New York society.” But those “stepping-stones” were slippery, and arrivistes could lose their footing. The trick was to be invited as a guest. This trick, advised Mrs. Lehr’s husband, Harry, was to “try to get invited for a week or two on someone’s yacht to see whether you are a success or not.” If not, “you can always . . . go back to New York without anyone witnessing your defeat.” If found to be acceptable, the newcomer was on probation, advised to “walk warily for the first season or two at Newport,” for “the battle isn’t won yet.” Harry Lehr was explicit: “Avoid Newport like the plague until you are certain that you will be accepted there. If you don’t, it will be your Waterloo.” His three “golden maxims” for a lady literally in waiting at Newport were: (1) “Be modest”; (2) “Never try to take any other woman’s man; (3) “Never try to out-dress or out-jewel the other women.”

For false aspirants to that inner circle, however, warnings were posted: Newcomers Need Not Apply. Wrote Elizabeth Lehr with an ironic tang, “Newport was . . . the playground of the great ones of the earth from which all intruders were ruthlessly excluded by a set of cast-iron rules.” “Dire indeed was the fate,” she explained, “of those . . . unwise enough to take a villa for the whole season, for in so small a community there was no escape for them. Every week their humiliation was brought home to them . . . as one after another of the all-powerful queens of Newport chose to ignore their existence.”

The pain of exclusion was excruciating. “Splendid balls and dinners every night,” Mrs. Lehr explained, “but not for them. . . . They could only sit in the palatial villa they had so rashly acquired and accept their defeat with what grace they could.” She detailed the exclusions—from the ladies’ drawing rooms, from the men’s private clubs. The newcomers might enter their Thoroughbreds in the annual Horse Show and win first prize, but the real prize eluded them. Or they may be observed skillfully playing tennis but never invited for a match. Few newcomers withstood more than a month of such “ostracism,” Lehr noted. They were seen in Newport—but found themselves invisible.

Harry Lehr, all acknowledged, was the “King” of Newport (a droll moniker from an evening in costume) who oiled the wheels of Society during the summer season. Maud Elliott pictured him “wearing the cap and bells as court jester,” while May Van Rensselaer called him “brilliant and eccentric.” Lehr, for his part, saw himself as the successor to the social maestro Ward McAllister (“I begin where Ward McAllister left off”).

A native of Baltimore, Henry (“Harry”) Symes Lehr (1869–1929) had started off modestly as one of seven children of a tobacco importer. In adulthood, working as a champagne commission salesman in New York, he was acquainted with affluent gentlemen eager to stock their cellars. His tailoring was impeccable, as were his manners and speech. He made a point of acquaintance with Society’s ladies, who found him charming and invited him to their parties. Known for his conversational flair, Lehr was befriended by the social queens of New York: Mrs. Stuyvesant Fish, Mrs. Oliver Belmont, Mrs. Hermann Oelrichs. Mrs. Astor hosted him herself, warming to Lehr’s incredibly bold gesture early in their acquaintance. Plucking red roses from a vase one evening, he held the bouquet against Caroline Astor’s “resplendent white gown,” declaring, “You need color.” (The dominant reds of the gown in Mrs. Astor’s full-length portrait of 1890 indicate that she heeded his advice. Annually Mrs. Astor reserved a seat for Lehr in her box at the Metropolitan Opera.)

These were the leaders of Society to whom, in 1899, Harry introduced an acquaintance, Elizabeth Drexel Dahlgren, the young, recently widowed heiress of the banking house founded by her grandfather Joseph Martin Drexel. Her late husband, John Dahlgren, had succumbed to a chronic pulmonary illness after just two years of marriage, and Elizabeth was sunk in mourning. Lehr’s attention had brightened her life, and one day at luncheon at Sherry’s in New York, he presented her to his friends. Recalled Elizabeth, “They were all charming to me,” “but I could not quite rid myself of the impression that they were taking stock of me.” Indeed they were. Leaving the restaurant, Elizabeth overheard Mrs. Oelrichs say, “I think she is delightful, Harry. We four are going to take her up. We will make her the fashion. You need have no fear.” Assured of her success, Harry promptly proposed, and the couple were wed in June 1901.

Elegant appearance to the contrary, Lehr was a penniless poseur who targeted the rich widow to secure his financial future and lifelong anchorage in Society. The truth surfaced on their wedding night when Harry admitted, wrote Elizabeth in her memoir, “King” Lehr and the Gilded Age, published many years after his death, “There is no romance, and never can be any between us. . . . Do not come near me except when we are in public.” The “brutal truth,” he said outright, was that he found Elizabeth to be “actually repulsive.” Lehr banked on the likelihood that the bride, a devout Roman Catholic, would not divorce him, especially since the shock might prove fatal to her beloved, frail, and fervently Catholic mother. He was right. Before their wedding, Elizabeth had promised to fund him amply, which she did until his death, twenty-eight years after their marriage.

“Pride came to my rescue,” Elizabeth wrote. “I would accept my destiny with what grace I could.” They were immediately “swept into the . . . set to which Harry Lehr belonged.” They were invited everywhere and reciprocated with parties of their own. Friends marveled at Harry’s display of loving care for his wife, calling her “precious” and fetching her wrap lest she be chilled (“Don’t catch cold, darling”). Elizabeth noted that “kind” and “motherly” Mrs. Astor smiled her approval (“So nice to see young people so much in love. . . . I am so glad to see dear Harry with such a charming wife”).

The charade continued at Newport, where everyone relied on Harry Lehr to enliven the social scene, to stage clever practical jokes (including cross-dressing), to assuage hurt feelings, and to smooth ruffled feathers among the rival queens who, on occasion, scheduled important parties on the same date and fought one another in a winner-take-all battle for guests who had been proffered two conflicting invitations. Lehr was known as “Cupid’s messenger,” smoothing quarrels and sometimes matchmaking to ensure himself a steady stream of invitations. The men of Newport Society never liked Lehr, but they welcomed his shepherding of their wives. In their absence during the business week, Harry Lehr kept the women amused.

The Harry Lehr era was at times notorious for its follies. If Newport became bored, Harry Lehr was on hand to freshen the scene with a keynote of “originality,” including a dinner party honoring a “Prince del Drago,” who turned out to be—surprise!—a monkey in evening dress. A fine time was had by all, though the hosts were chided in the press for disrespecting European royalty. Or consider the “Dogs’ Dinner” at which over one hundred Society dogs of all sizes feasted on stewed liver, shredded dog biscuit, and fricasseed bones on the Lehrs’ verandah. (“Elisha Dyer’s dachshund so overtaxed its capacities that it fell unconscious by its plate and had to be carried home.”) On a tip, an enterprising newsman leashed a dog, posed as a guest, and reported that the canines of Newport dined on pâté de foie gras. Once again Harry Lehr was reprimanded, this time from pulpits nationwide, denouncing him for wasting precious food and money that could have served the poor.

Surely another Society event would have been rich fodder for the press. The Servants Ball, hosted by Mr. and Mrs. Elisha Dyer, required that Society costume itself in “the correct apparel of ladies’ maids, valets, cooks, chauffeurs and footmen.” Harry Lehr came as a butler, Elizabeth as a ladies’ maid. However, “When the evening of the party arrived, no one had the courage to face their servants dressed in what appeared to be clothes purloined from their own wardrobes.” Thus the maids and manservants of Newport were given an evening off “so they should not witness their master’s and mistress’s departure for the ball.”

Came September, and Society departed for the city and the new social season, at which point in time, according to May Van Rensselaer, “the resort exports Triumph, Hope Deferred, and Mortification.” Free of the “cottagers,” the year-round tradesmen and artisans whom Harry Lehr called “Our Footstools” reclaimed their space, moving at will along Bellevue Avenue and Ocean Drive. For them, Newport was home, and neither Mrs. Astor nor the other cottagers need know that “Beechwood” and other summer palaces sometimes housed winter occupants who were later termed “squatters.”

The rare weeks when “the trees burst into their autumn flame” were the most cherished by “the descendants of the early settlers,” among them Maud Elliott, who savored these golden “Indian summer” of earliest autumn when Newport briefly became its old self. “The air is like champagne,” she wrote, “the sea burns ever more deeply blue,” and “society becomes more intimate.” In these weeks, tea is served by “ancestors’ fireplaces in an atmosphere graced with candlelight, old silver and old lace.”

Slumming It: Entertainment on the Lower East Side

The most exotic space in all Manhattan awaited Society on the occasional evening when the social calendar did not beckon the Four Hundred to a ball, a party, the opera, or the theater. In the spirit of adventure, some ladies and gentlemen prepared to venture to the infamous Bowery or to the Lower East Side. Novelty was in the air, and spirits ran high. The zoo in Central Park occasionally afforded daytime amusement, but the nighttime scenes at the lower end of Manhattan promised vivid glimpses of humanity at its most exotically alien. Friends who had already ventured recommended such an evening, and they promised greater entertainment than stereopticon photographs of the same scenes viewed in a parlor. They told of swarthy immigrant men hawking goods from pushcarts (bananas, shoes, suspenders), women in babushkas and shawls, and ragged, bare-footed street urchins running amuck. They reported a strange mix of odors and perhaps recommended that the ladies carry a perfumed handkerchief to dab if needed. Foreigners swarmed there, they said, and a stroll through the notorious Hester Street promised to be a lively and memorable two-hour diversion.

In preparation, the ladies must forgo jewelry and the gentlemen leave their silk top hats and walking sticks at home. Dressing down went against the grain of the Four Hundred, but understatement was the order of the evening. For their own protection, the Four Hundred were in camouflage when they entered the carriage for the ride far downtown. The ladies’ anxieties were soothed by the promise that a uniformed policeman would escort the party and provide protection. It was standard practice for a uniformed officer to accompany such parties and provide guided tours. (The Irish brogue of the policeman added to the flavor.)

Henry James had explored this nether region. He recalled aromas of peanuts and orange peel in the Bowery as “quite harmoniously Irish.” He observed alien facial features, the “Galician cheek,” the “Moldavian eye”—and in the Lower East Side, the innumerable Jews! (“There is no swarming like that of Israel when once Israel has got a start, and the scene here bristled . . . with the signs and sounds, inimitable, unmistakable, of a Jewry that had burst all bounds.”) James noticed that from the doorstep to the curbstone, the gutter, the pavement, every occupant used the street for “overflow.” He concluded that the “New York Ghetto,” meaning the Lower East Side, resembled “some vast sallow aquarium.” Looking to the future, he also referred optimistically to “The New Jerusalem.” The ladies and gentlemen of Society are not on record chatting about such a new epoch. Safely at home, proud of their daring, they doffed their slum wear, ordered their valets and personal maids to see to the cleansing and disposal of the garments of the evening, and resumed life as they knew it best.