Money Talks

Gospels of Wealth

Sacred and secular, Gilded Age voices chorused hymns to wealth and its beneficence. James McCosh, president of Princeton University during the Gilded Age (1868–88), opined in his book The Method of Divine Government that “God has bestowed upon us certain powers and gifts,” among them “the powers which wealth puts into operation.” (As one Protestant publication of the period proclaimed, “God has need of rich Christians, and He makes them.”)

The former Episcopalian Christian minister William Graham Sumner (1840–1910) became in 1872 a professor of political economy at Yale College and America’s most forceful advocate of the idea that human society advances through struggles and rivalries that result in the “survival of the fittest,” or the philosophy of “social Darwinism.” (Interference in this biological law of nature, he cautioned, might produce “the survival of the unfittest.”) Public morality, he was convinced, was best served by what became known as the Protestant work ethic, and he praised as the “forgotten man” whom he identified as the sober-minded citizen who took responsibility for family discipline, personal finance, and workplace reliability. He argued for free trade and condemned the philanthropies that he felt promoted idleness and dampened ambition. In his terms, however, “fitness” referred to a moral fitness for which all were eligible, while “survival” meant economic success. Sumner’s courses at Yale were so popular that students dubbed them “Sumnerology.” Of his numerous books, What Social Classes Owe to Each Other, published relatively early in his career, is often cited as his major contribution to conservative thought.

The coupling of wealth and its ecclesiastical equivalent seemed utterly natural to persons of financial success, such as Clarence Day Sr., a churchgoer whose workdays passed at the stock tickertape in his office. His son Clarence Jr. noted that his father attended Episcopal church services in the 1880s. “He liked St. Bartholomew’s,” he recalled. “The church itself was comfortable, and the congregation were all the right sort. There was Edward J. Stuyvesant, who was president of three different coalmines, and Admiral Prentice who had commanded the Fleet, and old Mr. Johns of the Times; and bank directors and doctors and judges—solid men of affairs. The place was like a good club. And the sermon was like a strong editorial in a conservative newspaper.”

Elizabeth Lehr, an observant Roman Catholic, cast her gimlet eye on certain clerics favored by the Four Hundred, both in the city and Newport, the seasonal locales of her adult life. “Going to church,” she observed, “was a social function,” for “everyone was religious,” and “the more successful in business you were during the week, the more devoutly you attended church on Sunday.” Mrs. Lehr noted that “everyone lionized the popular preachers; they were invited to the smartest houses in New York.”

The Episcopal bishop Henry C. Potter of the Diocese of New York was one of them. He was “stately and magnificent, a man of the world, a lover of rich food and rich houses,” Lehr observed. Bishop Potter “had actually two forms of saying grace before meals,” she noted, the first employed at the homes of wealthy hostesses and “delivered in a rich and fruity voice, ‘Bountiful Lord’ rolling the words round his tongue.” In the homes of “lowlier parishioners where the fare was of uncertain quality, he would begin meekly, in a minor key. ‘Dear Lord, we give thanks for even the least of these Thy mercies.” Mrs. Lehr was equally attentive to the aesthetic “Dr. ——,” the rector of “a fashionable New York church” who was “greatly in demand at Newport as a fashionable addition to dinner parties where the women described him as ‘magnetic.’” Observed Lehr, “Handsome and faultlessly dressed, he loved to carry about with him a string of amber beads which he fingered incessantly to display the lily-whiteness of his long slender hands.”

Gilded Age etiquette guides included advice for conduct in church, presuming that members of Society worshiped from the closed pews that were reserved for families, often over generations and secured by annual donations. (“Not very different from an opera box,” quipped one member of Society.) Neither synagogue nor mosque warranted a syllable. Some of the rules of conduct apply today; others are distinctly of the past. First, the gentleman must remove his hat upon entrance. If accompanied by a lady, he proceeds down the aisle with her to the pew, whose door he opens and makes way for her to precede him. He enters the pew, closes its door, and is seated. (“By no means enter an unoccupied pew uninvited.”) Above all, “one should preserve the utmost silence and decorum in church,” and “there should be no haste in passing up or down the aisle.” Further, “there should be no whispering, laughing, or staring.” Prayer books and hymnals ought to be provided for all but may be shared by worshipers.

For those who attend a church service “of a different belief” from one’s own, etiquette guides advised conforming to all “observances,” including kneeling and rising with the congregation. One caveat was explicit: “No matter how grotesquely some of the forms and observances may strike you, let no smile or contemptuous remark indicate the fact while in church.” Upon the conclusion of the service, one must not crowd the aisle but recess to the vestibule “quietly and in order” without “loud talking or boisterous laughter.” Gentlemen were strictly warned not to congregate “in knots in the vestibule or upon the steps of the church and compel ladies to run the gauntlet of their eyes and tongues.”

For many in Society, spiritual well-being was a matter more of practice than doctrine. “When Father went to church and sat in his pew,” Clarence Jr. recalled, “he felt he was doing enough. Any further work ought to be done by the clergy.” As young Clarence noted, Father contributed to the prestigious Charity Organization Society, as did the members of his clubs. The climate of opinion, however, shifted on behalf of the poor who were barely getting by on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. “All my friends do a great deal for the poor,” insisted Mrs. Astor, a touch defensively, adding, “their daughters are brought up from infancy to look upon their charity work as an important part of their lives.”

Captains of industry and Wall Street moguls, for their part, largely met the steely eyed reformers and dewy do-gooders with silence—or waved them off with a staccato flourish, such as, “I owe the public noting” or “The public be damned” (these gratis J. P. Morgan and William H. Vanderbilt). In late life, Cornelius Vanderbilt and John D. Rockefeller bequeathed fortunes for the founding of universities named for them.

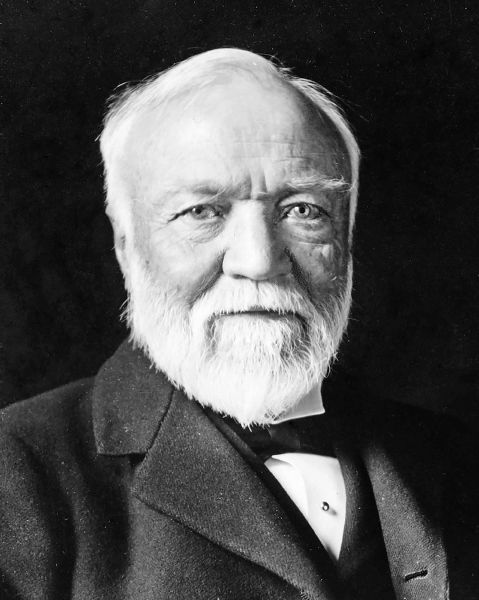

Meanwhile, a few Gilded Age defenders of great wealth came forward to advance the cause—and the faith as they came to understand it. Chief among them was Andrew Carnegie (1835–1919), the Scots-born industrialist and philanthropist who immigrated with his family to western Pennsylvania in 1848. A mentor loaned the precocious teenage “Andy” the money for an opportune investment in a railroad venture, and the favorable return showed Carnegie the value of finance. Profitable investments continued in rail and related industries, notably bridges and sleeping cars. By 1892, with a number of ambitious associates, Carnegie launched the steel company that bore his name: the Carnegie Steel Company. With a mansion on New York City’s Fifth Avenue (and a castle in Scotland), the ultrarich Carnegie married Louise Whitfield, the daughter of a wealthy New York merchant, and fathered a daughter, Margaret, but fretted about his vast fortune. (After the sale of his Carnegie Steel to J. P. Morgan in 1901, he was for some years the richest man in America.) Ultimately he dispensed large sums to build Carnegie Libraries throughout the United States, built Carnegie Hall, founded the Carnegie Museum and Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie-Mellon University) in Pittsburgh, and endowed numerous foundations that bear his name, including the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and the Carnegie Institution for Science. (Carnegie Medals are also awarded for acts of personal courage.) Carnegie nonetheless wrestled with the problem of what to do with all that money as it increased exponentially. His 1889 essay “Wealth” was reprinted as The Gospel of Wealth, casting his words in an aura of sanctity. The Gilded Age tycoons’ sons and daughters—and grandchildren—surely shuddered at Carnegie’s words, alarmed at his prescription for the dispersal of wealth, for he urged philanthropy instead of family inheritance.

Wall Street

New York native Henry James sailed home in 1903 after twenty years abroad to find the city shocking. New steel bridges and towering skyscrapers were mind-boggling, and he confessed, “I gave myself up . . . to the thrill of Wall Street, . . . the whole wide edge of the whirlpool.” A vortex of gains and losses, “The Street” swirled with shares of stocks that spiked to reap fortunes or plummeted to threaten bankruptcy. Gilded Age brokers and capitalists clustered at The Street, all minds monopolized by one strategic goal, money and power. As Broadway signified the theater and Fifth Avenue the mansions of the rich, lower Manhattan’s Wall Street was—and is—synonymous with the stock market.

Wall Street’s links with finance nearly hid its revered role in the founding of the nation. Schoolchildren of the mid-1800s pored over their McGuffey Readers textbooks to learn that George Washington, the father of the country, was sworn into office on the site in April 1789, taking the oath on a balcony of Federal Hall. As Gilded Age adults, those grown-up children knew Wall Street as the shrine of “the land of the almighty dollar,” according to the title of a memoir of 1892. (It is fitting that the “architect” of the US financial system, Alexander Hamilton, the first secretary of the Treasury, is interred near Wall Street in the cemetery of nearby Trinity Church.)

Perhaps a Gilded Age clerk or a mogul on his way to the exchange gave a passing thought to a founding mythic Mr. Wall as his occupational ancestor. In fact, the street was named for a wall, a wooden palisade, when the island of Manhattan was New Amsterdam in the 1600s. At the time, Wall Street featured a buttonwood tree under which speculators and traders gathered for transactions through the 1700s. The rudiments of the New York Stock Exchange were formalized in a “Buttonwood Agreement” of 1792 by which manipulative auctions were banned and commission rates established.

No Gilded Age businessman or trader, however, pondered the origin of The Street as he toiled on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange or gathered in offices around the glass-domed ticker-tape machines that “ticked” to telegraph the rise and fall of stocks. A flowing paper band printed abbreviated company names, together with the price and volume of each stock that was bought or sold.

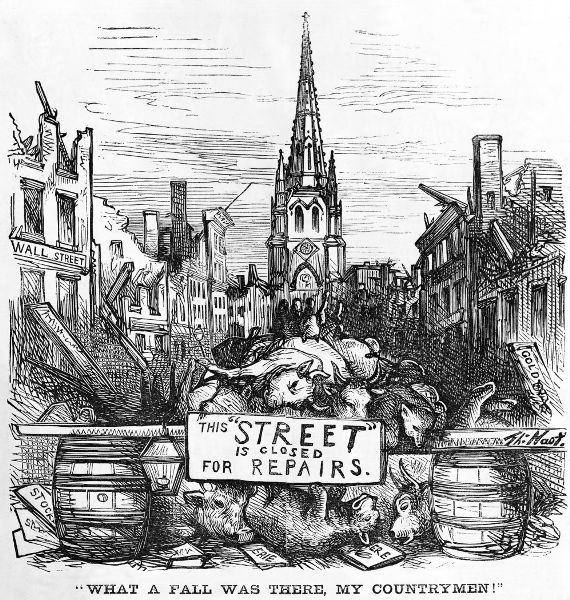

The ticker signaled gains or losses depending on the investor’s reliance on a “bull” or “bear” market, the two opposing symbols that pointed to expanding (bull) or contracting (bear) stock values. Fortunes could be reaped either way, though the origin of the two symbolic beasts remains murky. The Elizabethan sport of bull- or bear-baiting might have been the beginning, though some people believe that the aggressive bull lifting its horned head befits the idea of a market on the rise, while the bear’s muscular downward thrust of its clawed forepaw best indicates a downward trend. The political cartoonist Thomas Nast widely publicized these visual symbols in a cartoon in Harper’s Weekly following a market crash of 1869. Nast portrayed dead bulls and bears (wily fox too) heaped in front of a Wall Street sign reading, “This ‘STREET’ is closed for REPAIRS”—all against the background of the Trinity Church spire. A board game, perhaps a Gilded Age precursor to Monopoly, was retailed by 1883 and affirms The Street as the one and only habitat: Bulls and Bears: The Great Wall Street Game.

For a few people, great fortunes arose from the carnage of market collapse and other opportunities. Three Wall Street tycoons dubbed “Robber Barons” for unscrupulous maneuvers that inflated stock value and looted companies include Daniel Drew (b. 1797), a finagling short-seller in railroads, together with James (“Jubilee Jim”) Fisk (b. 1835), who parlayed accounting skills into a fortune as a trader and speculator. Jay Gould (b. 1836) completed the trio of speculators, but the name most closely allied with Wall Street finance in the era was John Pierpont (J. P.) Morgan (b. 1837), whose power helped stabilize the US financial system in the panic of 1907. Both celebrated and reviled for their financial connivance, these and other men represent financial victories that swirled from Wall Street.

Patience was seldom a strong suit, lamented the successful financier Henry Clews. “If young men had only the patience to watch the speculative signs of the times,” he insisted, “they would make more money . . . than by following up the slippery ‘tips’ of the professional ‘pointers’ of the Stock Exchange all the year round.” The author of Fifty Years in Wall Street (1908), Clews lamented that “few gain sufficient experience in Wall Street to command success until that period of life in which they have one foot in the grave.”

For much of the public, The Street remained a seductive mystery. The novelist Theodore Dreiser spoke for many when he quit searching for the logic behind the ups and downs. It was “useless,” he wrote, “to try to figure out exactly why stocks rose and fell.” “Anything can make or break a market,” he added, “from the failure of a bank to the rumor that your second cousin’s grandmother has a cold.” (George Sala suspected a businessman’s failure was rooted in high living, not market fluctuations: “When a business man comes to financial grief in New York, . . . it is generally held against him that he lived in ‘a brown stone house with a marble façade, kept fast trotting horses, and gave champagne suppers.’”)

Narratives of the era, not surprisingly, offer mixed views that are undershot with apprehension and awe, with at least one impression of the exalted Street emphatically iconoclastic. “Most of the business buildings were old,” recalled the disappointed Clarence Day Jr., whose railroader father took him to his office (38 Wall Street) on a spring Saturday morning of 1886. Seeing The Street for the first time, the ten-year-old boy was stunned by the drabness of the nation’s financial capital. “Many” of the buildings were “dirty, with steep, well-worn wooden stairways, and dark, busy basements.” The senior Mr. Day, oblivious of his young namesake’s views, prepared to take command at the office he ran like a tight ship, his clerks on duty six and a half days weekly, the drear of Wall Street the furthest thing from his mind. His office ticker tape was a compass to guide business direction, and young Clarence noted its presence; but his judgment on the ambient scene was clear: “the southern corner of Wall Street” was “one of the dingiest.”

One symbol of The Street took hold and persists into the twenty-first century: the stock market as a gambling casino. “The head-quarters of the fiercest gold-gambling the financial world had ever seen,” fairly gasped George Sala, who visited the US in 1879–80. Another New York visitor in these years declared, “Here fortunes are made and fortunes lost by that system of gigantic gambling which has come to be known as ‘dealing in stocks.’” Blanche Oelrichs, whose family was snugly ensconced in the Astor Four Hundred, fretted that “the Tempo in Wall Street began to resemble that of a roulette wheel.” Publishing under the pen name of Michael Strange, Oelrichs remarked that to play the wheel, “you had to be ‘on’ to a hundred and one gadgets concealed under the table, before you made your bet!” She felt a “Vanity Fair atmosphere of incessant money troubles moving lavalike beneath a spurious surface of contagious gaiety”—and beneath it all, the “poisonous uncertainty of how the bills were to be paid.” In these years, she heard of Wall Street failures as a “fact.”

Edith Wharton tallied Wall Street winnings and losses in her tales that painted stark portraits of sad men who lacked financial wizardry or the blessings of Lady Luck. A self-confessed “child of the well-to-do,” Wharton proclaimed her ignorance of “feverish money-making in Wall Street” during her youth, though her febrile pen exposed Society’s secrets by Wharton’s early forties. Her best seller of 1905, The House of Mirth, profiles the ghostly figure of the “slightly stooping” and “tired” Mr. Hudson Bart, whose New York business days are spent “down town” but who cannot meet the incessant financial demands of his socially prominent wife and daughter. Joining them for an occasional summer Sunday at Newport or Southampton, “he would sit for hours staring at the sea-line from a quiet corner of the verandah, while the clatter of his wife’s existence went on unheeded.” Writes Wharton, “It seemed to tire him to rest,” and she prepares her reader for the scene in which Mr. Bart, at death’s door, comes home at midday to announce financial catastrophe in two words: “I’m ruined.”

Financial collapse well served newspaper gossip columns and fiction’s story lines, as did the true-life accounts of the Caesars of The Street. The daughters of Wall Street kingpins, however, sensed the toll taken on fathers who ran the ongoing race for the gold. Blanche Oelrichs recounted that her father succeeded on the “Exchange,” although much “strain and exhaustion” dogged his business days. Elizabeth Lehr, for her part, described her father, Joseph William Drexel (partner at Drexel, Morgan & Co.), as “a big, bearded man with fine dark eyes” who was “perpetually tired,” often falling asleep at the dinner table, “more exhausted than a field labourer.” (Fed up contending with his partner, J. P. Morgan, Drexel withdrew from finance to become a philanthropist and arts patron.)

The bulls and bears of The Street may seem far afield of the mansions of Fifth Avenue, but Edith Wharton reminds us they were welded together in the Gilded Age, that Mrs. Astor and her Four Hundred were partnered in a dance of getting and spending at both ends of Manhattan. A gentleman character in Wharton’s The Custom of the Country channels Wharton’s own dark judgment that “society” consists of “a muddle of misapplied ornament over a thin steel shell of utility.” The “steel shell,” he continues, “was built up in Wall Street, the social trimmings were hastily added in Fifth Avenue; and the union between them was . . . monstrous.”

The union was monstrous, perhaps, to those whose stock certificates were suddenly worthless. And it was monstrous to those who waited in vain for the postal envelope of invitation bearing the return address of “Mrs. Astor.” It was monstrous, what is more, to those whose families reached back to—and ruled—the quieter New Amsterdam era before the onset of the crass “Invaders,” as did Wharton’s gentleman character. As did the family of Edith Newbold Jones Wharton, who claimed that very ancestry and whose memoir, A Backward Glance, chronicles her presence at a Society ball in a New York winter season, at lawn tennis in Newport in the summertime, and on the deck of a yacht sailing the Mediterranean Sea. In short, as critical as she was, Mrs. Wharton enjoyed the fruits of Wall Street amid the society of the Four Hundred.

Top-Drawer Schools

For Girls

“Pity the girl who is subjected to the endless routine which is supposed to fit her for a position in American Society, or to qualify her for the British peerage.” The Gilded Age memoirist Frederick Martin continued his lament: “Her education commences from the day of her birth” with schooling that includes “daily lessons in riding, driving, all kinds of physical culture, and from morning until evening she learns afresh something physically or mentally.” Martin had a point. Nannies and governesses were pressed into service to shape little girls in pinafores into ladies of the future, and a schoolroom with a tutor could be a space set aside in a Fifth Avenue mansion. (Daisy Hurst Harriman recalled school days in the home of J. P. Morgan.)

Not every Gilded Age socialite was to the manor born. Evalyn Walsh McLean, transplanted from Colorado to the East, recalled her family’s decision that “by some school magic,” she was to “become a lady,” which meant boarding schools in Paris and in New England, followed by a French governess who became her finishing school. The young heiress was thus readied for material splendor, European tours, Newport, Palm Beach, and eventual possession of the famous Hope diamond.

A Society girl submitting or surrendering to her family’s wishes was privileged to attend a boarding school in one of the following, each name appropriately gendered:

- 1.Miss Hall’s, in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, was founded in 1898 by Mira Hinsdale Hall, a graduate of Smith College.

- 2. Miss Porter’s was established in 1843 in Farmington, Connecticut, by Sarah Porter, who encouraged horseback riding and tennis but insisted on a curriculum weighted in classical and modern languages, mathematics, and the sciences.

- 3. Rosemary Hall was founded in 1890 by Mary Atwater Choate at Rosemary Farm in Wallingford, Connecticut. Classical languages, history, art, and French were prominent in the curriculum, and students were attired in uniforms.

- 4. The Ethel Walker School, founded in 1911 in Lakewood, New Jersey, was intended to prepare girls for higher education and was deliberately set in opposition to the finishing schools that emphasized social decorum.

For Boys

As cosmopolitan young gentlemen of the future, the boys of the Four Hundred were expected to be proficient in German and French, to travel abroad, and to converse easily with visiting eminent Europeans at the US dining tables of Society. Their New York families employed German or French governesses to see to sons’ (and daughters’) language skills. Eventual entrance to Harvard, Yale, or Princeton intermingled in school decisions, but three preparatory schools were the approved channel to the approved college. All were situated in locales far from the temptations of the cities, and all are affiliated with the Episcopal Church, whose congregants comprised a majority of the members of Society:

- 1. St. Paul’s School, dating to 1856 and affiliated with the Episcopal Church, celebrated the bucolic but austere setting of wild, wooded New Hampshire. Its innovations in athletics in the later 1800s included ice hockey and squash. The New Yorker Clarence Day Jr., attended St. Paul’s before attending Yale.

- 2. St. Mark’s School, founded in 1865, is located in Southborough, Massachusetts, and was from the first an Episcopal preparatory school. Its Tudor architecture echoes the English medieval period.

- 3. Groton School was founded in 1884 by the Reverend Endicott Peabody, whose first and last names signified family prominence dating to the founding of the Pilgrims in 1619. Located in Groton, Massachusetts, the school enjoyed the support of prominent figures of the Gilded Age, including J. P. Morgan. A regimen of cold showers was thought to instill rigor in the boys of Groton.

Dollar Princesses

From the shores of the Pacific, from the banks of the Monongahela, and from the great plains of the West . . . came millionaires with their wives and children destined to change the old order into something entirely new. . . . New blood was infused into feeble stock, and as a result Venus Victrix, dowered with loveliness and dollars, set forth to conquer England.

—Frederick Townsend Martin, Things I Remember

“Great marriages . . . were being arranged all around me!” marveled one young New York socialite, as impecunious British and European aristocrats seized opportunities to refill the family coffers with the fortunes of newly rich Americans. The necessary ingredients: one American daughter of vastly wealthy parents and one titled British or European male of marriageable age. For rich Americans, royalty was minted with the nuptials; for the European peerage, vast American fortunes were the price of admission. Remarked a connoisseur of the scene, “The heiress makes no secret of her admiration for a title; she knows that her money will work wonders, and often some neglected stately home has looked in pride again under her benign influence.”

The transactions often commenced with the arrival in London of the rich American girl with her mother, who made it known that the family had money and promptly displayed a willingness to spend lavishly for soirées and musicales at which members of the aristocracy were introduced. The Titled American, a quarterly publication, listed the names of eligible titled bachelors, the acreage of their estates, their income, their family seats, and their military affiliation in such distinguished regiments as the Coldstream Guards. Arrangements proceeded swiftly. From the 1870s to the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, some 350 American heiresses became brides of British aristocrats.

Figure 63. An American lady’s musicale and her daughter to be “royalized” by marriage to an eligible aristocrat in the audience

At times, the mercantile essence of the matches prompted uneasiness and, on one occasion, an outright public diatribe when Joseph Pulitzer’s World featured a blistering editorial in May 1881: “There is the sordid aristocracy of the ambitious matchmakers, who are ready to sell their daughters for barren titles to worthless foreign paupers, and to sacrifice a young girl’s self-respect and happiness to the gratification of owning a lordly son-in-law.”

The sacrifice and gratification continued unabated. April 1893, for instance, saw the betrothal of the sixteen-year-old American Cornelia Martin, daughter of Bradley Martin and Cornelia Sherman Martin, whose fortune of nearly $6 million ($1.5 billion today) was a surprise inheritance from her father, Isaac Sherman, a retired merchant who had not been considered a man of wealth during his lifetime. The selection of the bridegroom, the Englishman William George Robert, fourth Earl of Craven and Viscount of Uffington, proclaimed a Gilded Age linkage of the New World to the centuries-old aristocracy of England. The extravagantly wealthy Bradley Martins considered their daughter’s wedding gifts to be, literally speaking, “fit for a princess.” The Martins, for their part, conferred today’s equivalent of $11 million on the family of the groom. After the wedding, it was reported that the bridegroom was heavily tattooed and appeared at the church with his trousers rolled above his boots.

The Bradley Martins sought to royalize themselves with their daughter’s wedding, a point they emphasized in a society ball they threw soon after at the Waldorf Hotel. The guests were asked to adorn themselves in costumes of the nobility—extending to the era of knights and castles, of kings and queens—to which their newfound riches entitled them. The New York Times, along with the Herald and others, devoted thousands of words to the events, and readers evidently relished the accounts:

The much-heralded fancy dress ball given by Mr. and Mrs. Bradley Martin took place at the Hotel Waldorf last night. . . . Standing upon a velvet and rug covered dais at one side of the smaller ballroom of the Waldorf Hotel last night, against a background of rare tapestries and under a canopy of velvet, Mrs. Martin received the salutations of more than 600 men and women, one and all members of the society worlds of New York and other large American cities, and all in their gorgeous robes and garbs personating those Kings and Queens, nobles, knights, and courtiers whose names and personalities take up pages of history, and who, during the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries pervaded the different countries of Europe. . . . As the society of the metropolis has grown larger, and wealth, luxury, and the knowledge of the art of living have increased, these successive costume balls have in every instance surpassed in elegance of dress and in lavishness and perfection of appointment their predecessors. . . .

Mr. and Mrs. Bradley Martin were the first to arrive. Their carriage stopped at the entrance at 10:15. When the carriage door was opened Mr. Martin stepped lightly to the sidewalk and aided Mrs. Martin to descend. At half-past 10 a group of carriages arrived together, and before 11 o’clock the stream of guests had become continuous.

What brilliance there was within for the knights and noblemen and the jeweled ladies, who passed through, and there was only an occasional glimpse for the group outside of a brilliantly lighted hall, with a broad stairway at the end. . . .

The grand ballroom was quite a scene of splendor. The eye scarcely knew where to look or what to study, it was such a bewildering maze of gorgeous dames and gentlemen on the floor, such a flood of light from the ceiling, paneled in terra cotta and gold, and such an entrancing picture of garlands that hung everywhere in rich festoons. The first impression on entering the room was that some fairy god-mother, in a dream, had revived the glories of the past for one’s special enjoyment, and that one was mingling with the dignitaries of ancient regimes, so perfect was the illusion.

—New York Times, February 10, 1897

Not all of these marriages proved to be cause for celebration. One socialite, Consuelo Alva Vanderbilt, the daughter of the New York multimillionaire railroad baron William K. Vanderbilt and the Alabama southern belle Alva Erskine Smith, became the Duchess of Marlborough upon her marriage in 1895 to Charles Spencer-Churchill, His Grace the ninth Duke of Marlborough. The young bride was forced into the marriage by her socially ambitious and conniving mother (who intercepted letters sent to her from the apparently unworthy Winthrop Rutherfurd, a wealthy New Yorker directly descended from Peter Stuyvesant and the man Consuelo loved), and she reportedly “wept all night at the conclusion of the settlements between the Duke and her father,” an arrangement amounting to upward of the equivalent of $68 million in railroad stock. She wept once again behind her veil at the altar, for the Duke was as indifferent to his bride as she to him. Consuelo later wrote of herself as a “pawn” in her “mother’s game,” while the duke called her “a link in the chain.” Among her numerous jewels was a “heavy tiara,” which “invariably produced a violent headache.”

A headache was a small price to pay for many “daughters of Liberty” who “spend their money lavishly” and “believe in the value of advertisement,” according to Frederick Townsend Martin (uncle of the newly minted Countess). “They like to see society paragraphs about their jewels and their gowns; and they love to know that all the world . . . may read about their vast improvements of their husband’s estates.” Martin continued, “To them, it represents business, not snobbishness, and they regard a position in the peerage much as other people look upon an investment.”

Martin’s memoir is laced with such marital investors. Jeanie Chamberlain of New York became Lady Naylor-Leyland, and the “tall, green-eyed” Minnie Stevens married the grandson of the first Marquis of Anglesey in a ceremony attended by the Prince of Wales, whose gift was a Louis XIV clock. Mary Goelet (b. 1878), heiress of a New York real estate fortune with a dowry of some $20 million, became the Duchess of Roxburghe upon marriage to Henry Innes-Ker, eighth Duke of Roxburghe, in 1903. The couple settled at Floors Castle, which the Duchess furnished with rare seventeenth-century tapestries. A “remarkable” devotion to all things British prompted Frederick Martin to marvel at American women’s ability to “adapt themselves to the conditions of a new life in a new country.” Some, he felt, “forget their nationality,” such as Lady Arthur Butler (née Ellen Stager), who “has never revisited America since her marriage.” Others, Martin conceded, wisely hide their “home-sickness.”

Newspaper Wars

“Go West, young man,” advised Horace Greeley, the legendary editor of the New York Tribune. With the Civil War over, fortune favored men who boldly ventured, said Greeley, to “grow up with the country.” Two ambitious newspapermen had other ideas. They headed East. One was a successful newspaper publisher on the West Coast, the other in a riverfront city in the Midwest, but both had their sights set on New York. To William Randolph Hearst (1863–1951) and to Joseph Pulitzer (1847–1911), success meant success in Gotham. The two became fierce rivals in the business of newspaper publishing. Their fights were known as circulation wars, and both papers—Hearst’s Journal and Pulitzer’s World—were expressions of their publishers’ imagination, fierce drive, and keen business instincts. Each had his finger on the pulse of the public.

The arena Hearst and Pulitzer entered had a rich history from colonial days, and by the years following the Civil War, a thicket of newspapers deterred all but the most aggressive newcomers. In addition to Greeley’s Tribune, New Yorkers of the Gilded Age had the Evening Press, the American, the Sun, the Morning Advertiser, the Sunday Mercury, the New York Times, and others. “The vigor and brightness” of these and other American papers impressed a British visitor, James (Viscount) Bryce, who marveled that “nothing escapes them; everything is set in the sharpest, clearest light.” He declared US newspapers to be “influential in three ways—as narrators, as advocates, and as weathercocks.” As Bryce saw, the newspapers’ influence on public opinion was incalculable. Politics, culture, world events, scandals, the comings and goings of the social world’s elites—all were reported and, in turn, shaped public attitudes toward personal and civic life. What is more, the papers’ advertisements fostered the new consumer culture. The ads for home furnishings, for the latest fashionable clothing, for wine and spirits, carriages and motor cars helped to define the modern standard of living. Bryce cautioned, however, that to be competitive, a modern newspaper could only succeed with “the support of hundreds of thousands,” for it must serve “the bulk of the people.”

Until the 1890s, the principal New York paper was the Herald, the paper founded by James Gordon Bennett Sr. (1795–1872) and sustained by his raffish, socialite sportsman son, Gordon Bennett. The founding father set the principles of the Herald, to “give all the news freshly, fully, and faithfully from all parts of the world” and “to make the Herald a cosmopolitan journal par excellence.”

The young Bennett, groomed to succeed his father from boyhood, upheld key policies of the Herald in the first years of the Gilded Age. “My father has made the Herald a great paper,” he proclaimed, adding, “I mean to make it greater . . . no matter what cost.” The young press lord grasped the potential that eluded his father: that journalism could create the story. Reporters need not be passive bystanders waiting to spring into action when news broke. No single story need expire at day’s end, for a gripping serial that spanned days, weeks, or months boosted sales, subscriptions, and the lifeblood of newspapers: advertising.

Gordon Bennett capitalized on this idea with a groundbreaking saga of the search for the missing Dr. David Livingstone, the British explorer who disappeared in the heart of Africa. Bennett tapped the Welsh American journalist Henry Morton Stanley to seek Livingstone and financed the venture in pounds sterling. Herald readers followed Stanley’s dispatches from the opening of the Suez Canal in November 1869 to Cairo, to Constantinople (today’s Istanbul), to Odessa, the Caucasus, Persia (now Iran), from Bombay (Mumbai) and onward toward Africa. To the Herald’s advantage, not a credible word had surfaced about the missing Livingstone. Finally, on November 10, 1871, near Lake Tanganyika (now Tanzania), Stanley was face-to-face with “the venerable European traveler” and uttered the classic line, “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” (Livingstone lifted his cap, smiled “cordially,” and answered, “Yes.”) A lengthy letter from Livingstone to Gordon Bennett (dateline: East Africa) was printed in the Herald to quell all doubts about authenticity. The lesson for the modern newspaper was clear: over a sustained period of time, a paper could sell itself to a public that was held in suspense and willing to shell out coins to a street-corner “newsie” or bills for a subscription.

The Herald declined when Gordon Bennett, facing new competition from Pulitzer’s World, cut the paper’s price (from three to two cents), spent lavishly, and raised the price of advertising. Bennett was a wealthy man, but his paper lost circulation and found itself outstripped by Pulitzer and by Hearst’s Journal in the mid-1890s. His Herald was overpowered by the two insurgents from the West. In the pattern familiar in Gilded Age New York, new money eclipsed old.

Joseph Pulitzer seemed an unlikely candidate for press lord of New York. An educated Jewish immigrant from a bankrupt Hungarian merchant family, he arrived in the US in 1854, knocked about in low-wage jobs, and settled in the vibrant city of St. Louis, where he penned an account of a fraudulent job search and sold the story to a German-language newspaper. Prominent men noticed the gifted young man, helped him get work as a clerk for a railroad, and gave him space to study the law. Pulitzer passed the Missouri bar in 1868 but found middling success as an attorney and eagerly became a reporter on the Westliche Post, the German newspaper that had published his account of job fraud. He became an American citizen, married, fathered the first of seven children, saved his money, and invested $3,000 in the Post. He sold his share at a profit and in 1879 bought two papers that merged into one: the Saint Louis Post-Dispatch (to this day the city’s leading paper). Though Pulitzer was extremely sensitive to ambient noise, suffered from wretchedly poor eyesight, and spoke English with vocal inflections of his native Hungary, he was attuned to the feelings of the American working class and crafted the Post-Dispatch as the voice of the people. Abuses in city government and tax evasion by the rich were the paper’s stock-in-trade and guaranteed Pulitzer’s success.

By 1881, Pulitzer was ready for New York. He purchased the World from the financier Jay Gould and launched his World on Sunday, May 13, with an editorial titled “Our Aristocracy”: “The new World believes that . . . an aristocracy ought to have no place in the republic—that the word ought to be expunged from the American vocabulary.” The “true aristocracy,” observed a fellow newspaperman, “was the man who by honest, earnest toil supports his family in respectability, who works with a stout heart and a strong arm.” The populist note that served so well in St. Louis was ripe for New York, and the success of the World was tangible by 1890, when visitors could observe the city from the top of the World Building (sometimes called the Pulitzer Building), a 309-foot structure capped with a glittering dome, the tallest building in New York and soon to be known by the sobriquet “skyscraper.”

The World initially prospered at the expense of its rivals. By 1890, its daily circulation numbered 185,672, while weaker rivals, including the Herald, the Tribune, the Sun, and the Times, tallied circulations of 90,000, 80,000, 50,000, and 40,000, respectively. The World successfully touted its reliable facts couched in gripping prose, a mantra that the reporter Theodore Dreiser heard in the city room on his first day of work at the paper. “I looked about the great room of the New York World as I waited patiently and delightedly,” he recalled, “and saw pasted on the walls printed cards which read: Accuracy, Accuracy, Accuracy! Who? What? Where? When? How? The Facts—The Color—The Facts!”

Then came William Randolph Hearst. The son of a fabulously successful mining magnate, real estate tycoon, and cattle rancher, young Hearst reportedly disappointed his father, George Hearst, by opting for a career in newspapering. A graduate of St. Paul’s School and Harvard, the young man showed talent in his chosen vocation by making a success of the San Francisco Examiner in the Pacific coastal city that was flush with rival newspapers, among them the Morning Call and Alta California. Like Pulitzer, Hearst considered himself a populist and filled the Examiner’s pages with exposés of financial and municipal corruption. With much of his family fortune at his disposal (one-half of the largesse following his father’s death, thanks to his indulgent mother), Hearst tapped family money for his New York Journal, willing to take losses for the time being. It soon became apparent to Joseph Pulitzer that Hearst’s Journal was gunning for his World.

From 1895 and beyond, the two press lords were locked in combat. The World stayed true to populism in its support, for instance, for William Jennings Bryan’s campaign for president in 1896, while the Journal held to the political center. Both newspapers, however, succumbed to “yellow journalism,” the nickname for colorful news unencumbered by facts. With encouragement from the paper’s publisher and editors, the reporters could fan the flames of an event and enlarge it by a factor of ten, of a hundred. A small fire could be a conflagration, a light tap on the wrist a full-blown assault. The flamboyant reporting often crossed the line into fiction that lacked the barest basis in carefully researched and verified fact. The term “yellow journalism” possibly derived from the yellow ink favored by some newspapers but also referred to “The Yellow Kid,” drawn by Richard F. Outcault in a comic strip called Hogan’s Alley. The “Kid” first appeared in the World but later migrated to the Journal. Yellow journalism in these years meant outsized headlines, trumped-up stories, exaggerated accounts of events, flashy kaleidoscopic layouts, untraceable pseudosources. Today’s tabloid newspapers are sometimes traced to the yellow journalism of those days. (The novelist and Atlantic Monthly editor William Dean Howells penned a portrait of a cynical, slick yellow journalist, Bartley Hubbard, in The Rise of Silas Lapham [1885].) The two papers declared a cease-fire in 1998, both having lost vast sums covering the Spanish-American War.

Resentment at meager earnings led the city’s newsboys, or “newsies,” to strike against Pulitzer and Hearst in the summer of 1899. For two weeks, the boys held firm. They held rallies, encouraged the public to boycott the papers, blocked others from hawking the papers on the streets, and destroyed bundles of freshly published editions. The circulation of the World and the Journal suffered badly, and the press lords bowed under pressure and raised the boys’ income.

Hearst and Pulitzer remain forefront names in today’s media, Hearst for its Hearst Media Group for broadcasting and publishing, Pulitzer for prizes in excellence in journalism. The newsboys’ strike of 1899 became the basis of a 1992 musical film, Newsies, followed by a Broadway production of the same title that ran from 2012 to 2014.