The Whiff of Scandal

They struck like storms, the scandals that both shocked and titillated Gilded Age New York when the periodic eruptions burst into view, raising pulses in the drawing rooms from Fifth Avenue to Newport. They ranged from marital splits to murders, some bannered to the world at large, others kept secret in the precincts of Society.

Divorce and Mrs. Astor

During the Gilded Age, divorce was shocking—until it wasn’t. At first, Gilded Age divorces were “discussed in a low breath with immense disapproval.” Elizabeth Lehr, heir to the Drexel banking fortune, remarked that her mother believed divorce to be “an unbearable disgrace” and refused to allow the word to be uttered in her presence. Immediately after the Civil War, the guest lists that included divorcées were puzzles at best, land mines at worst, for two ex-partners in the same room augured ill for any social occasion. It took James Van Alen “literally hours,” he complained, to devise a seating plan “that would give no one an embarrassing neighbor” at a dinner in his Newport cottage. Renowned for his fine table, Van Alen confided to a companion, “This dinner has almost driven me mad. I thought I should never be able to seat my guests properly without putting some former wife by her ex-husband.”

By the late 1880s, however, “such reticences vanished,” according to the Knickerbocker doyenne May Van Rensselaer. She sketched the newer social scene: “Today divorced persons greet their severed halves with no more embarrassment than . . . acquaintances who had once taken a stormy voyage on the same ship.” Divorce, she hinted, had become so commonplace that marital longevity was outdated. To prove the point, she quoted a dowager who boasted that she was “probably the only woman in Newport who for thirty years has had the same cook—and the same husband.”

Mrs. Astor, ever the regal exemplar of the best practices of Society, had long adhered to older traditions, and persons embroiled in “the divorce courts” were immediately banished from the guest list for her annual ball. Now, however, Mrs. Astor’s daughter Charlotte (Mrs. James Coleman Drayton) “figured in a divorce case” of her own when “incriminating” letters to her lover, Mr. Hallett Alsop Borrowe, the vice president of Equitable Life, were published in the press. Society held its collective breath as invitations to a reception at the Astor home were sent after the divorce had been finalized. Elizabeth Lehr spoke for everyone when she affirmed that whether or not Mrs. Astor chose to “apply her rigid code to her own daughter,” Society “would follow her faithfully” because “the Queen could do no wrong.” As guests entered the salon, Mrs. Lehr recalled, “They sighed with relief.” Mrs. Charlotte Augusta Drayton was “standing by her mother, calmly helping her to receive her guests.”

In this, as other instances, Mrs. Astor’s gracious, placid demeanor deflected firestorms of scandal as effectively as a modern-day superheroine’s armor. In admiration, Elizabeth Lehr, who was frequently Mrs. Astor’s guest, observed that “no one ever knew what thoughts passed behind the calm repose of her face.” “She had so cultivated the art of never looking at the things she did not want to see,” Mrs. Lehr continued, “never listening to words she did not want to hear, that it had become second nature for her.”

It might also be said that Caroline Astor was the reigning Queen of Denial. New York had long buzzed with “gossip concerning the latest doings of William Astor.” Mrs. Lehr and others heard the “rumours,” the stories that “circulated of wild parties on board his yacht,” Nourmahal (translation: “Light of the Palace”), that “grew more and more exaggerated as they flew from mouth to mouth.” However, “their curiosity was never satisfied.” “Upon inquiries about her husband, Mrs. Astor would placidly reply, ‘Oh, he is having a delightful cruise. The sea air is so good for him. It is a great pity I am such a bad sailor, for I should so much enjoy accompanying him. As it is, I have never even set foot on the yacht; dreadful confession for a wife, is it not?’” Her smile, said Mrs. Lehr, held “nothing but pleasant amusement over her inability to share her husband’s interests.” Mrs. Astor held her ground. She always “spoke of him in terms of the greatest affection and admiration—‘Dear William is so good to me. . . . I have been so fortunate in my marriage.’” “There was something disarming in her quiet loyalty,” concluded Elizabeth Lehr, a woman ever aware that her own marriage was a façade.

Inexcusable

Nothing quiet was ever associated with James Gordon Bennett Jr., the ultrawealthy heir of the New York Herald, the paper that flourished under the leadership of his father. From his teens, “young Jim” was notoriously ill mannered and daring, and in New York, he was best known for collecting showgirls, hurling insults, throwing punches, and imbibing great quantities of alcohol. His escapades were legendary, from riding naked atop a coach to tugging at the tablecloths in a restaurant, sending the silver, crockery, and linens crashing to the floor. Called Gordon Bennett in his adult years, he fervently committed to the ongoing success of the Herald, but his major claim to fame was, and remains, his leadership in sport. He promoted ballooning, automobile racing, tennis, and polo. As a yachtsman, he owned and raced a series of sailing craft, and he served as commodore of the New York Yacht Club and raced for the America’s Cup.

Scandal finally caught up with Gordon Bennett in 1877, when he called at the Fifth Avenue home of Dr. William May for the celebratory New Year’s custom of calling on friends and family. By now in his midthirties, the eligible bachelor was thought to be seriously courting May’s daughter, Caroline. The entire day was set aside for these calls, and each household offered snacks and beverages, many flowing from a silver punch bowl. A good many of these libations were “spiked,” and by the time Bennett reached the May home to call on Miss Caroline and her family, he had “acquired his limit.” Before the assembled company, Bennett approached the fireplace, unbuttoned his trousers, and relieved himself. (Rumor amplified the offence from the fireplace to the piano.) The courtship was abruptly terminated, and Bennett began wearing chain mail under his shirts lest an outraged member of the May family shoot him in defense of the family honor. When he finally faced off in a duel with Caroline May’s brother in Slaughters Gap, Delaware, on January 7, both shots missed, the May family honor was “satisfied,” and the disgraced Gordon Bennett fled to Europe for an extended period. In later life, he sailed his steam yachts in the Mediterranean, studiously avoiding American shores.

Gordon Bennett’s years as a sportsman, however, promised further scandal, this time in Newport. A polo match found the Herald publisher on the same team as William Douglas, who, for whatever reason, “did not pass the ball to Bennett when it was coveted by the newspaper man.” According to May Van Rensselaer, “Bennett, furious, put spurs to his pony, charged down upon Douglas and struck him across the head with his mallet. Douglas pitched off his horse, senseless, and never recovered his full health.” Mrs. Van Rensselaer concluded that “the matter was hushed up, as so many scandals were in that day.”

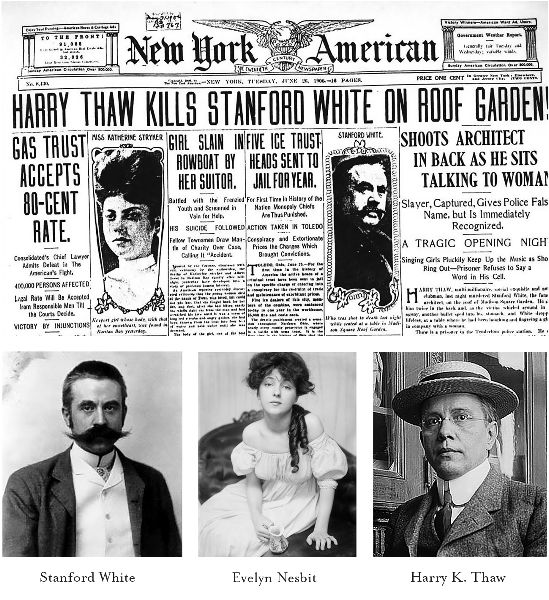

Deadly Triangle: Nesbit, White, Thaw

By far, the most publicized, juiciest scandal of the Gilded Age was the murder of the celebrity architect Stanford White in a love triangle that ensnared the multimillionaire Harry K. Thaw and his wife, the famous young actress and model Evelyn Nesbit.

As a talented “vassal” of the Four Hundred and a partner in the leading American architectural firm of McKim, Mead, and White, Stanford White (1853–1906) had been the force behind such grand projects as the Triumphal Arch at Washington Square Park, the second Madison Square Garden, and the palatial Newport “cottage,” christened “Rosecliff,” of the heiress Theresa Fair Oelrichs. White’s marriage in 1884 to the socially prominent Bessie Springs Smith and the birth of his son, Lawrence Grant White, three years later suggested that the prolific architect had settled into a family life of privilege and professional esteem as he produced winning designs for some of the Gilded Age’s most noted residences and civic buildings.

To White’s ultimate detriment, this was not the case. A flamboyant man-about-town who sported a flaming red mustache and a flaring opera cape, White reveled in the New York nightlife of champagne and oh-so-very-young alluring women. Unlike the stage-door Johnny who might treat his chorine to dinner at a lobster palace or the Society gentleman hosting a cherie aboard his moored yacht, Stanford White kept a lavishly furnished private apartment on West Twenty-Fourth Street. One room, paneled entirely in mirrors (ceiling too), was furnished with a green velvet sofa and, dangling from the ceiling, a red velvet swing. In this room, White entertained—and was entertained by—the desirable young ladies who posed in “varying degrees of undress.” And it was here that the forty-seven-year-old architect had lured the underage siren Evelyn Nesbit.

A famous model and a New York stage actress by sixteen, Florence Evelyn Nesbit (1884–1967) had begun life inauspiciously as the daughter of a western Pennsylvania attorney and a homemaker who encouraged their little girl to sing and dance, though Mr. Nesbit’s death, when Evelyn was eleven, left the family nearly destitute. Evelyn’s mother moved the family to Philadelphia in search of better opportunities, and her budding and beautiful daughter began to work as an artist’s model while in her early teens. Evelyn’s image was soon widely used by commercial advertisers, and she became one of the first of the nation’s “cover girls,” gracing the pages of Cosmopolitan, the Delineator, and Ladies’ Home Journal, among others. Her face and figure were most famously captured by the magazine illustrator Charles Dana Gibson, whose pen and brush portrayed her as the quintessential “Gibson Girl.” Sultry and winsome, Evelyn Nesbit combined girl-next-door innocence and ripe sensuality.

In addition to White, Nesbit had caught the eye of the handsome young actor John Barrymore, but another rival was soon smitten to the point of obsession. By 1900, weary of untold hours as a mannequin, she had turned to the stage as a chorus girl costumed as a “Spanish maiden,” then in the popular play Floradora and then, in 1902, featured on Broadway in the role of Vashti, a gypsy girl in The Wild Rose. The nightly sight of her gliding beyond the footlights dangerously inflamed the passion of a rich man with a troubled history of mental breakdowns, paranoia, and addiction to alcohol and other drugs.

Harry K. Thaw (1871–1947), heir to a Pittsburgh coal and railroad fortune, had been in and out of mental institutions from his youth but was nonetheless pampered from boyhood by doting parents who indulged their only son’s every whim while downplaying his symptoms of mental disturbance. By the age of thirty, he was notorious for the sex, alcohol, and drugs that fueled his mentally turbulent waking hours. With Evelyn Nesbit, Thaw acquired a deadly new habit. He attended forty performances of The Wild Rose before arranging a meeting. Thaw wined and dined Evelyn, lavished gifts on her, and in 1904 persuaded her to join him on a European sojourn chaperoned by her mother.

The itinerary was frenetic and peculiar. Instead of the usual tourist destinations, Thaw arranged a stay at a Gothic castle in Austria, by which point Evelyn’s travel-fatigued mother had returned to New York. Evelyn later told friends that Harry whipped and sexually assaulted her, keeping her trapped for weeks in the prison-like castle. Evelyn had also confessed to Thaw her prior relationship with Stanford White, though cloaking her admission in terms of assault. According to Evelyn, White had gained the confidence of her mother to enjoy her company and then, one evening, brought Evelyn to his private apartment, where he gave her champagne and raped her while she was unconscious. (That, at least, was Evelyn’s courtroom testimony in the trial to come.) From that moment on, Harry Thaw’s fury was to know no bounds.

Thaw’s repeated proposals of marriage had been refused thus far, but Evelyn found herself at a crossroads. As she knew from her penniless mother’s struggle, money mattered. She was now over twenty years old, a perilous age for a Gilded Age starlet harboring hopes of matrimony. Though it was known that Stanford White was her good friend and patron, her reputation would be ruined if she were publicly exposed as White’s mistress. Harry Thaw’s abject apologies for mistreating her during their European trip seemed sincere, and he promised to be on his best behavior (like a “Benedictine monk”) once they were married.

On April 4, 1905, Evelyn became Mrs. Harry Kendall Thaw, and the couple took up residence at “Lyndhurst,” the grand Thaw estate in Pittsburgh. At the insistence of Harry’s mother, Evelyn renounced the stage. Her life at Lyndhurst, however, became another prison, for the spirited social life that Evelyn anticipated never materialized in the wealthy but puritanical ambience of the Thaw household ruled by Harry’s mother.

Thaw, meanwhile, nursed his paranoid jealousy toward the suave, prominent architect he loathed as a rival. On the evening of June 25, 1906, while Thaw and his wife were in New York attending a performance at the rooftop garden theater of Madison Square Garden, Thaw fatally shot White in the head. The architect died instantly on the rooftop of the very building he had designed. A witness saw Evelyn hurry to her husband, embrace him, and say, “I didn’t think you would do it this way,” while Thaw said he was “glad.”

Charged with first-degree murder, Harry Thaw was jailed in New York’s Tombs, where his meals were catered by Delmonico’s restaurant. For the upcoming “trial of the century,” his mother spent tens of thousands of dollars on attorneys and on doctors who testified that Harry was temporarily driven mad by the revelation that his wife had been victimized sexually. It was understandable, they argued, that he should be bent on avenging the wrong. Thaw’s mother insisted on a defense based on temporary insanity to spare her son the stigma of being cast as a madman. The press relished the spectacle. Through Mrs. Thaw’s lawyers, Evelyn was paid to play the melodramatic role of the wronged maiden in her testimony. A first jury deadlocked. Thaw was retried and in February 1908 was found not guilty by reason of insanity and sentenced to lifelong incarceration at the Matteawan State Hospital for the Criminally Insane at Fishkill, New York, where his deluxe accommodations befitted his wealth.

The Thaws were divorced in 1915, the same year that Harry—having managed a prior aborted escape—was declared sane and officially released from confinement. Evelyn Nesbit, for her part, pursued a long, if modest, career on stage and film but would be largely remembered for a starring role in the fatal ménage that cost one of the Gilded Age’s most famous architects his life.