Muckrakers

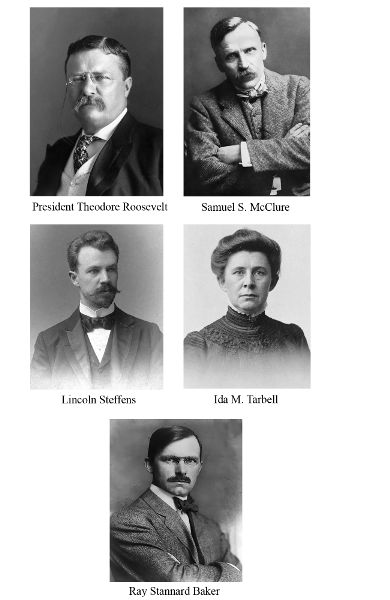

“War” in the oil business, “Shame” in the cities, “Anarchy” in the mining camps in the West. These and other hot-button issues allied the journalists known for the “literature of exposure.” They relished the job title—investigative reporter—for its dignity and serious purpose but were blindsided by the attack that came in March 1906 and forever branded them. Their hub was New York City, but the attack came from the nation’s capital; and the assailant was a New Yorker from an old Knickerbocker family who happened to be president of the United States.

“The Man with the Muck-Rake” was the title of the featured speech at the 1906 white-tie dinner of the journalists’ Gridiron Club in Washington, DC. The speaker was President Theodore Roosevelt, and his title referred to a centuries-old allegory, The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678), a book widely circulating in the Gilded Age. Like legions of American churchgoers, the president knew the story from boyhood Sunday school—how a young man named Pilgrim seeks spiritual salvation on a journey stalled by various detours and temptations. Pilgrim meets, for instance, a roadside downcast figure who fails to see heavenly brightness because he relentlessly rakes the muck of the material world. Roosevelt remembered the episode and seized his moment. A hunter, he knew how to sight a target. He fired, and the audience of editors and reporters endured a forty-five-minute double-barreled attack on investigative journalists, whom the president denounced as modern-day versions of the man who “fixes his eyes . . . only on that which is vile and debasing.” In tones that reportedly “sizzled” with “moral disdain,” Roosevelt blasted the writers whose sole focus on society’s “filth” made them “one of the most potent forces for evil.” His ammunition was Bunyan’s “Man with a Muck-Rake,” his target the US journalists whose relentless exposés of graft and corruption threatened, he feared, to stir an outraged public to the point of rebellion. Altogether, he charged, they were Bunyan’s modern-day “Man with the Muck-Rake.”

Roosevelt’s moniker stuck, and the investigative journalists became “muckrakers.” Recalled Lincoln Steffens, “I did not intend to be a muckraker; I did not know that I was one till President Roosevelt . . . pinned it on us.” Perhaps, after all, the president had missed the mark, for he gave this cohort of journalists and certain fiction writers new distinction. He was especially incensed by the publication of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle (1906), the best-selling novel that exposed Chicago’s major meat processers for marketing meat that was unfit for human consumption. Sinclair’s readers were also alerted to the brutal working conditions in the packing plants, to the exploitation of the immigrant workers toiling for meager wages, to their substandard housing and the fragility of their new American lives. Roosevelt was especially chilled by the novel’s promotion of socialism as a remedy for these ills.

In fact, the president was a muckraker of sorts, rooting out corruption of the municipal New York Tammany Hall machine in the 1890s when he was the city’s police commissioner and the scourge of the saloons that were centers of graft. He wrote privately in a letter of 1903 about “the dull, purblind folly of very rich men, their greed and arrogance,” and he noted the “corruption in business and politics.” Roosevelt feared, however, that the muckraking journalists sewed public distrust and put governance itself at risk. His culprits were the popular magazines that contained “a little truth” but seduced the public with “lurid” and “sensationalist . . . outpourings.”

One of Roosevelt’s major targets was McClure’s. In this, he hit the bull’s eye. The Gilded Age coincided with the Golden Age of American magazines, and several published muckraking exposés, including Collier’s, Cosmopolitan, Hampton’s, Independent, Success, and American. The headquarters of the muckraking movement, however, was indisputably located on the third floor at 743 Broadway, the editorial headquarters of McClure’s Magazine, named for the Irish-born, physically diminutive Samuel Sydney (S. S.) McClure (1857–1949).

McClure was an entrepreneur, not a reformer. Business success in a capitalist system was his goal, not muckraking. A wretchedly poor immigrant from Ireland, he spent an impoverished boyhood and youth on an Indiana farm with his mother, stepfather, and three brothers. Restless and precocious, the indomitable young man worked his way through Knox College in Galesburg, Illinois, and made his way to Boston, where he successfully headed a new bicycle magazine, the Wheelman. New York City beckoned, and in 1884, McClure partnered with a former college friend, John Sanborn Phillips whose temperate personality counterbalanced the mercurial McClure. Their first venture was a syndicate that bought stories and articles from promising and well-known authors and sold them to newspapers at modest prices for simultaneous publication, often in Sunday supplements. After eight years operating the syndicate, McClure and Phillips launched their magazine, McClure’s. The first issue appeared in June 1893. The timing was terrible. A major depression hit the nation that year (and continued for the next six years), forcing McClure to rely on loans to keep the magazine afloat before it turned a handsome profit from wide circulation and heavy advertising.

Depression aside, the moment was ripe. Print publication was in its heyday for fiction and nonfiction. Bulk paper was cheap enough, the US rail and postal systems keyed for distribution, new photo-engraving processes affordable, and ambitious writers abundant. McClure knew how to find them at home and abroad. He plucked Ray Stannard Baker from the Chicago Record and Lincoln Steffens from the New York Evening Post. He climbed flights of stairs to a Paris garret to recruit Ida Tarbell, whose sketch he had bought for the syndicate and remembered for its flair. This crop of writers meshed with others at work on fiction—Stephen Crane, Jack London, Willa Cather, and others. Face to face, McClure won them over and signed them up. (Ida Tarbell recalled McClure’s “vibrant, eager, indomitable personality that electrified even the experienced and the cynical.”)

They came to McClure’s headquarters in New York like filings to a magnet, then scattered to far-flung locales to work. Steffens ventured by rail to Minneapolis, St. Louis, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Chicago, and other major cities, and his articles in McClure’s exposed the venality and corruption that betrayed the citizenry of urban America. Baker went west to Colorado’s mining camps and found “the worst conditions of industrial anarchy then existing anywhere in America.” His report “The Reign of Lawlessness: Anarchy and Despotism in Colorado” appeared in McClure’s in 1904. Tarbell, meanwhile, spent untold hours in western Pennsylvania and Ohio courthouses researching documents to prove the corruption that gave Rockefeller’s Standard Oil a monopoly. Her series ran in McClure’s for eighteen months, 1902–3 and cost McClure $50,000 in salary support for nearly a decade of her meticulous research ($1.4 million today). The money was well spent, for Tarbell fulfilled her promise to give readers a “straightforward narrative, as picturesque and dramatic as [she] could make it.”

The successful, profitable McClure’s was the Irish-born founder’s golden opportunity. For the US public, it was a pipeline to the social, political, and economic woes that afflicted the nation in the Gilded Age and begged for remedy. The Four Hundred knew little or nothing of the goings-on at McClure’s. New York, they presumed, was theirs alone as they reveled in opulence along Fifth Avenue and in Newport and theirs alone on Wall Street. The muckrakers, all the while, were diagnosing the nation’s pathologies in terms backed up with hard facts. They held a mirror to the public and showed a nation blighted by child labor, lethal workplaces, substandard housing and wages, and businesses swollen into monopolies. Baker spoke for them all when he said, “It seems profoundly important that the public know”—and know “exactly.” The muckrakers readied the ground for a cadre of Progressives who advanced new policies and legislation at statehouses and in Washington, DC, from the 1910s. Reprinted in book form, Lincoln Steffens’s articles on urban corruption became The Shame of the Cities, and Ida M. Tarbell’s series on the petroleum giant became The History of the Standard Oil Company. Together with Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, they are considered American classics.