Chapter Four

Land of 10,000 Lakes and

10,000 Prisoners: Minnesota's

Correctional System

Learning Objectives

- Identify some of the causes and consequences of mass incarceration

- Describe the demographics of Minnesota's prison population

- Describe the structure of corrections in Minnesota (state and county)

- Describe the statistics as they relate to offenders under supervision

- Explain the different levels of correctional facilities in Minnesota

- Identify the use of probation in Minnesota

- Describe how Minnesota responds to pregnant inmates

- Articulate some of the issues associated with an aging prison population

- List the job duties of a probation officer and correction officer

- Identify intermediate sanctions used in Minnesota

- Define pardons and the role of the Pardon Board

- Explain what is PREA

Incarceration is one of the main forms of punishment to which lawbreakers in our society may be subjected. Punishment is an undesirable or unpleasant outcome, typically justified under the rubrics of deterrence, incapacitation, retribution, or rehabilitation. On deterrence, first articulated by Cesare Beccaria in 1764, we imprison people to prevent them from committing future crimes. Beyond

specific deterrence

for the offender, time behind bars also offers the possibility of

general deterrence

for the wider public, wherein the prisoner serves as a cautionary tale of expected consequences (see Stafford & Warr, 1993). Penal confinement also physically separates offenders from the community, thus removing or reducing their ability to carry out future crimes

(Zimring & Hawkins, 1995). Of course, prison also serves a retributive function, as a way of “getting even” with the offender; an idea often associated with the Biblical tenet of

lex talionis

or “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth.” Owing to the five “pains of imprisonment” (Sykes, 1958), including the deprivation of liberty, deprivation of goods and services, deprivation of heterosexual relationships, deprivation of autonomy, and deprivation of security, incarceration ensures offenders also receive their “just deserts” for wrongdoing (von Hirsch, 1976). Finally, prison time can also help reform and rehabilitate the offender so they will not commit the crime again.

Minnesota has been in the business of corrections since 1853, when the first adult territorial prison was established in Stillwater after Congress in 1850 allocated $20,000 to complete the six-cell, two-dungeon facility (Dunn, 1960). Prior to this time, criminals were held at two of the state's military posts, Camp Ripley and Fort Snelling. In the early days, the prison had problems with escapees, counties failing to pay for their prisoners to stay at the facility, contract prison labor disputes, fires, wardens with little training in penology, bed bugs, and poor air quality, among other issues. In 1905, Congress approved construction of new buildings close to the site in an effort to transform Stillwater into the “best penal structure in the country” (Dunn, 1960, p.151). Minnesota Correctional Facility–Stillwater in nearby Bayport, replaced the original prison in 1914. By the turn of the twentieth century Minnesota was well on its way to becoming a modern penal state.

Today, Minnesota has a wide range of adult and juvenile, male and female facilities and programs. The Department of Corrections (DOC) was legislatively created in 1959 to “Reduce recidivism by promoting offender change through proven strategies during safe and secure incarceration and effective community supervision.” They work to achieve this mission through many policies, programs, and initiatives; however, the state is not the only one in the business of corrections. There are county-level jails and programs, as well as non-profit organizations that all work with offenders in a variety of capacities. This is because of the state's wide use of intermediate sanctions, which as defined by Minnesota Statutes §609.135 subd b include:

incarceration in a local jail or workhouse, home detention, electronic monitoring, intensive probation, sentencing to service, reporting to a day reporting center, chemical dependency or mental health treatment or counseling, restitution, fines, day-fines, community work service, work service in a restorative justice program, work in lieu of or to work off fines and, with the victim's consent, work in lieu of or to work off restitution.

This chapter provides an overview of corrections in Minnesota, with particular attention paid to how state, county, and community correction services are administered.

Prison Statistics

The United States incarcerates more people than any country in the world, both per capita and in terms of total people behind bars—approximately one in every 100 adults (Travis, Western, & Redburn, 2014). America's state and federal prison population has increased more than sixfold in 40 years from 200,000 inmates in the mid-1970s to approximately 1.5 million today, and if we include local jails, the total is closer to 2.3 million (Sentencing Project, 2015).

The

causes

of mass incarceration are legion: “zero tolerance” policing, the war on drugs, mandatory and longer sentencing, the trying of juveniles as adults, the prison-industrial complex, and the “New Jim Crow” (for a discussion, see Alexander, 2012). The

consequences

are serious (Stuntz, 2011): prisons are overcrowded, understaffed, and dangerous places; prison gangs have institutionalized (Skarbek, 2014); and ex-offenders struggle to access education, employment, and training or to find housing, transportation, and basic healthcare upon release.

Nationwide, including offenders supervised in the community, 6,899,000 people were under correctional control in 2013 (Glaze & Kaeble, 2014). This represents a decrease of .06% from 2012, which is in part attributable to a decline in the probation and jail populations. The federal prison population declined for the first time since 1980, but the state prison rate increased. Furthermore, since 2010, the female population grew by 3.4%, which is attributed to a growth in the total jail population (Glaze & Kaeble, 2014).

In 2013, 189 per 100,000 Minnesotans were incarcerated, which is the second lowest incarceration rate, behind Maine, in the country (National Institute of Corrections, 2015). The U.S. national average is 395 per 100,000 people, and the state with the highest incarceration rate is Louisiana with 847 per 100,000. While this may be encouraging to Minnesota, globally, a rate of 189 per 100,000 is still very high. For example, if we looked at Minnesota as a country it would be ranked the 12th highest out of 57 countries in Europe, 10th highest of 31 countries in Asia, 3rd highest out of 12 in the Middle East, and 10th highest out of 53 in Africa (International Center of Prison Studies, 2015).

The prison population in Minnesota on July 1, 2014, was 9,929 adult inmates, of which 456 inmates have a sentence of life

with

the possibility of parole and another 110

without

the possibility of parole (Minnesota Department of Corrections, 2014). These sentences are given for the crime of murder in the first degree as defined by Minnesota Statutes §609.185. Minnesota is currently a

non-death penalty state, but did have the death penalty a century ago (for a discussion, see

Chapter Eight

). In addition to the above, another 299 offenders were juveniles certified as adults in the criminal justice system. Minnesota Statutes §260B.125 allows for certification “when a child is alleged to have committed, after becoming 14 years of age, an offense that would be a felony if committed by an adult, the juvenile court may enter an order certifying the proceeding for action under the laws and court procedures controlling adult criminal violations.” Refer to

Chapter Six

for a more complete discussion of juvenile certification.

Offenders committed to the Commissioner of Corrections (sent to prison versus local jail) committed the crimes that are displayed in

Figure 4.1

. Since 2004, an average of 17.2% have been incarcerated for criminal sexual conduct, 13.9% for homicide, and 10.7% for assault. In addition, on average, 19.7% are incarcerated for drugs and another 7.2% for burglary (Minnesota Department of Corrections, 2015). In looking at felony-level crime, in 2013 there were 15,318 offenders sentenced. Thirty-two percent of these sentences were for person crimes, approximately 30% for property, and the remaining for other crimes, which include crimes like felony-level DWIs and non-person sex offenses (Minnesota Sentencing Guidelines Commission, 2014).

Figure 4.1. Number of Minnesota DOC Inmates by Offense Type on July 1, 2014

The length of time an inmate spends in prison is a very important variable as we look towards programming, costs, over-crowding, rehabilitation, and so on. A discussion of sentencing practices in Minnesota and the Minnesota Sentencing Guidelines is found in

Chapter Nine

. In should be noted that in 2013, almost three-quarters (72%) of felony offenders did receive a sentence per the guidelines, the remaining received mixed (1%), aggravated (4%), or mitigated departures (23%) (Minnesota Sentencing Guideline Commission, 2014). At the federal level, in March 2015, 53% of inmates were serving sentences 10 years or longer and the rest are fewer than 10 years as shown in

Figure 4.2

. In Minnesota, the average length of time an offender served in 2009 was 2.3 years. This number represents an increase of nearly 38% since 1990; however it is less than the national average of 2.9 years (PEW Charitable Trust, 2012).

Figure 4.2. Length of Sentences for Federal Inmates in March 2015

Jail Statistics

In 2012, the average daily jail population was 6,531 (Minnesota Department of Corrections, 2014). Hennepin County, home to the most populous city in the state, Minneapolis, also has the largest and busiest jail facility, which is operated by the Sheriff's Department. The facility includes two separate buildings, which together hold 839 beds. Each year the Hennepin County Sheriff's

Office books 40,000 offenders into their jail, generally for pretrial or awaiting hearings (Hennepin County Sheriff Office, 2015). In addition, Hennepin County has an Adult Corrections Facility to provide short-term (less than a year) custody and programming for 477 adult offenders (Hennepin County, 2015c). In 2012, it was selected by the National Institute of Corrections and Urban Institute as one of the six learning jail sites in the country to pilot Phase II of the Transition from Jail to Community (TJC) initiative (Urban Institute, 2012). This comprehensive model is designed to improve reintegration into the community from the jail, increase public safety, and reduce recidivism. Results from Phase I show promise. Phase II results are not yet available.

The second largest jail facility is Ramsey County Jail, which has 500 beds (Ramsey County, 2015) and like Hennepin County, they also have an Adult Corrections Facility.

Figure 4.3. Rates of Correctional Population in Minnesota and Nationally

Demographics of Minnesota's Prison Population

Gender

Consistent with national trends, men significantly outnumber women in Minnesota prisons. Since 2004, men have consistently comprised between

93%–94% of the total prison population (Minnesota Department of Corrections, 2014c). Minnesota Department of Corrections Policy 202.045 (2014) provides guidelines for “evaluation, placement, and treatment of offenders who claim to be undergoing transgender treatment, or are identified as transgender or gender-variant, and to assure offender safety and access to appropriate medical/mental health care.”

Education

Per Minnesota Department of Corrections Policy 204.040 (2010):

The minimum educational standard for all DOC offenders is a verified high school or GED diploma. The educational goal for all DOC offenders is preparation for and/or completion of post-secondary training or education. Adult facilities will provide eligible incarcerated offenders with comprehensive educational programming including literacy, General Education Development (GED) and high school diploma, Special Education, transition to post-secondary, post-secondary, enrichment, and other programs designed to prepare offenders for successful reentry into society.

In short, if DOC inmates do not have a high school diploma or GED they are required to go to school. If they refuse, they are not eligible for other work assignments.

In looking at education levels, the percentage of prison inmates with at least a high school diploma/GED equivalent has doubled since 2004. In breaking down the percentages even more, in 2013, for example, 16.8% have a college degree or higher, 26.7% have a GED, 25.6% have a high school diploma, 25% have completed grades 9–11, and the rest have completed 0–8th grade, other, or unknown (Minnesota Department of Corrections, 2014c). In looking at state data as a whole, 92.1% of people ages 25 or older have a high school/GED equivalent, of which 32.6% have earned a bachelor's degree or higher (U.S. Census Bureau, 2015). In 2012, the DOC released a report that highlighted the following additional education statistics:

- 2,450 offenders are enrolled in education programs on any given day.

- 632 offenders earned a GED or high school diploma in fiscal year 2011.

- Education classes had over 9,000 offender enrollees during fiscal year 2011.

- 644 career/technical certificates and diplomas were completed in fiscal year 2011.

- The Minnesota Department of Corrections ranks second among the 52 state Adult Basic Education consortia in number of student instructional hours. (Minnesota Department of Corrections, 2012a)

Table 4.1. Minnesota Prison Population by Gender and Education from 2004–2014

Race

The issue of race and incarceration is an important topic in Minnesota and elsewhere. Since 2004 the percentage of those incarcerated has not been proportional to the racial make-up of the population as a whole. As can be observed in

Table 4.2

, whites are underrepresented in Minnesota prisons and jails, while Hispanics, blacks, and Native Americans are overrepresented (Sakala, 2014). According to the U.S. Census Bureau, for example, only 5% of the population in Minnesota is black, but one out of every three inmates is black. In looking at federal statistics, in March 2015, 38% of the inmates were black, 59% were white, 2% were Native American, and 2% were Asian. Furthermore, 34.2% of inmates were Hispanic (Federal Bureau of Prisons, 2015a).

Table 4.2. 2010 Minnesota Incarceration Rates by Race/Ethnicity

In 2014, the American Civil Liberties Union issued a report highlighting disparities in sentencing to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Some of the highlights of their report include: (1) Sentencing imposed on black males is 20% longer than those of whites for similar offenses in federal prison; (2) The odds for black and Latino offenders being sentenced to incarceration and for longer periods of times compared to whites is greater in some jurisdictions; (3) blacks disproportionately are sentenced to life without the possibility of parole (and it is even more pronounced for juveniles) and the death penalty.

In 2009, Minnesota legislators passed the Disproportionate Minority Contact Act (Minnesota Statutes §260B.002), which states:

It is the policy of the state of Minnesota to identify and eliminate barriers to racial, ethnic, and gender fairness within the criminal justice, juvenile justice, corrections, and judicial systems, in support of the fundamental principle of fair and equitable treatment under law.

Minnesota also has some of the “deepest economic disparities in the nation based on race and while the reasons are complicated, involvement in the criminal justice system is one important factor driving such disparities” (Minnesota Department of Human Rights, 2013). In Minnesota, the disparity between whites and blacks with criminal records is four times higher than the national average. This is perhaps one of the reasons why in 2014, Minnesota became the first state to enact a “Ban the Box” law prohibiting criminal history checkmark boxes on employment applications (Minnesota Department of Human Rights, 2013). Ban the Box laws aim to reduce the stigma attached to having a criminal record.

The Ban the Box requirement has been in effect for public employers in Minnesota since 2009 and is designed to provide job candidates with an arrest or conviction with more opportunities to be evaluated on their skills and experience

when applying for positions with private employers. The law does not require an employer to hire any candidate with a criminal background, and employers may still conduct background checks. Ban the Box simply requires an employer to wait until later in the hiring process—at the interview stage or when a conditional job offer has been extended—before asking the applicant about their criminal record or conducting a criminal background check (Minnesota Department of Human Rights, 2013).

Age

Inmates in prison are getting older in both state and federal prisons, and elderly inmates represents one of the fastest growing populations in prisons. Sixteen percent of state and federal inmates are age 50 and older, with Minnesota having one of the smallest percentages (American Civil Liberty [ACLU], 2012). Mandatory minimums and longer sentences mean some prison facilities operate like nursing homes for some inmates. Elderly inmates impact how prisons do business, most notably on costs (see section later in chapter labeled Costs of Corrections

), but also on programming, movement policies, structural design, and other related issues. In addition, according to the ACLU (2012), housing elderly inmates requires more staffing (and training) because of various reasons, including more assistance with day-to-day activities and protection from mental and physical abuse from younger inmates.

Table 4.3. Age of Inmates in Minnesota State Prisons

Religion in Prison

Prisoners, like everyone else, have a right to believe in whatever religion they chose. Furthermore, a prison cannot coerce or force an inmate to participate in a religious practice or belief (

Lee v. Weisman

, 1992). There are two key pieces of legislation that provide for religious freedom in prisons and these include the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Person's Act of 2000 (for state inmates) and the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 (for federal inmates). Refinement of what exact practices are permissible has occurred through legislation since these acts were passed. For example, in

Holt v. Hobbs

(2015), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that it was wrong to force a Muslim inmate to shave his beard. In Minnesota, state law mandates that

[f]acilities provide all offenders with reasonable opportunities to pursue individual religious beliefs and practices, within facility budgetary and security constraints. When considered necessary for the security and good order of the institution, the warden my limit attendance at or discontinue a religious activity. Attendance at or participation in religious activities may not be restricted on the basis of race, color, nationality, sex, sexual orientation, or creed. Offenders are not required to attend religious services. (Minnesota Statutes §241.05)

Community items are stored by the facility, but offenders can designate personal religious items. Offenders also are allowed to purchase religious items, but all religious items must be approved and adhere to rules of the facility. For example, there is a designated time and place to use religious artifacts. Each correctional facility has a space designated for holding religious services and “a trained and qualified facility chaplain to oversee the reasonable delivery of religious services to all faith traditions.” If an offender has a religious diet, moreover, it is adhered to as long as the facility has the budget and security restraints. Donated food is not allowed (Minnesota Department of Corrections, 2015c). Some facilities have also created policies as they relate to religious head coverings. The Federal Bureau of Prisons, under Policy 5360.09, also permits the wearing of head coverings (yarmulke, kufi, headband, crown, turban, etc.) and even identifies what colors each of the various types of head coverings can include (U.S. Department of Justice, 2004).

Minnesota facilities have several faith-based programs. InnerChange Freedom Initiative is one such example that has been a part of Minnesota's prison programming since 2002. This program helps offenders “prepare for re-entry through educational, values based programming that connects spiritual development with educational, vocational, and life skills programming” (Duwe & Johnson, 2013, p.4). Some of these programs include religion-specific elements,

like Christian religious services and Bible study and prayers, as well as other types of programming, including substance abuse education, cognitive skill development, mentoring, and seminars. Research has shown this is effective at reducing recidivism and is cost-effective; it saved the Minnesota Department of Corrections $3 million over a six-year period (Duwe & Johnson, 2013).

Pregnant Inmates

Since 2004, approximately 6–7% of the total prison population in Minnesota has been women (Minnesota Department of Correction, 2015). Female inmates have different needs than male inmates, most notably as it relates to pregnancy and childbirth. Approximately 6–10% of females nationwide enter prison pregnant (Gerrity, 2013). Minnesota was the twentieth state to pass an anti-shackling law in regards to pregnant women and became the first state to pass legislation mandating that correctional facilities offer all pregnant women and women who have given birth in the past six weeks doula services. The legislation went into effect July 1, 2014, for state facilities and all other correctional facilities must be in compliance by July 1, 2015 (Office of the Revisor of Statutes, 2014). The law forbids the use of restraints (with strict exceptions) on women who are known to be pregnant or have given birth during transportation, labor, delivery, and three days postpartum.

In addition to banning the use of restraints and requiring doula services to be offered, the legislation mandates that all women be given pregnancy tests as well as testing for sexually transmitted diseases upon arrival to a correctional facility; additionally, educational materials regarding pregnancy, birth, breastfeeding, and parenting must be provided to all pregnant women and those who have given birth in the previous six weeks (Office of the Revisor of Statutes, 2014). Both of these allow women to not only become aware of a pregnancy, but also provide them with all the necessary information regarding what to expect.

The legislation also states requirements in regards to mental healthcare and treatment if it is needed; these provisions are in effect for all pregnant women and women who have given birth in the past six months. It allows for these women to receive mental health assessments and any treatments that may be necessary including medications and therapy (Office of the Revisor of Statutes, 2014).

Minnesota's Department of Corrections

The Minnesota Department of Corrections is one of the main components of the criminal justice system in this state. It provides a vast range of services

in an effort to improve community safety, rehabilitate offenders, and ensure justice is served.

Structure

The governor appoints a commissioner of corrections to lead the Department of Corrections. The commissioner has a broad range of responsibilities, including the operation of adult and juvenile correctional facilities in the state, oversight of probation and parole, service on the Minnesota Sentencing Guidelines Commission, and administration of the Community Corrections Act. Upon entering office, the commissioner

shall take and subscribe an oath and give a bond to the state of Minnesota, to be approved by the governor and filed with the secretary of state, in the sum of $25,000, conditioned for the faithful performance of the commissioner's duties. (Minnesota Statutes §241.01)

Two deputy commissioners, one tasked with facilities and another tasked with community corrections, support the commissioner. In addition, there is an assistant commissioner who oversees operation support and another who assists the deputy commissioner of facilities. A chief executive officer (warden) leads each facility, while seven different division leaders direct community corrections.

The Department of Corrections also utilizes the services of four legislatively mandated advisory groups (Roy, 2013), which include:

-

Advisory Task Force on Women and Juvenile Female Offenders in Corrections

. This task force is mandated by Minnesota Statutes §241.71 to “promote and advocate gender and culturally responsive services for women and girls in the criminal and juvenile justice systems.” They do so by “(1) suggesting model programs to receive funding, (2) reviewing and making recommendations on matters affecting female offenders, (3) identifying problem areas, and (4) assisting the Commissioner in seeking improved programming for female offenders” (Minnesota Department of Corrections, 2015).

-

Interstate Adult Offender Advisory Council.

This council is mandated by Minnesota Statutes §243.1606 to oversee the administration and operation of the interstate movement between compacting states for adult offenders. More information about interstate commissions for adult offenders can be located at http://www.interstatecompact.org

.

-

Interstate Compact for Juveniles, Advisory Council

. This council is mandated by Minnesota Statutes §260.515 to oversee the administration

and operations of the interstate movement between compacting states for juvenile offenders.

-

Health Care Peer Review Committee

. This committee is mandated by Minnesota Statutes §241.021 “To review and evaluate the quality of on-site and off-site offender care and treatment, including deaths of offenders, in order to evaluate and improve the quality of care and reduce morbidity and mortality too.”

Minnesota Correctional Facilities (MCF)

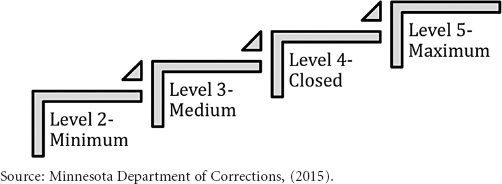

Minnesota Statutes §241.021 defines licensing and supervision of facilities. As illustrated in

Figure 4.4

, Minnesota's correctional system has four levels of adult custody classification, ranging from two (minimum) to five (maximum). MCF–Oak Park Heights is the one and only maximum-security facility in the state, designed specifically to house people who pose extreme risks to the public. They are held in the Administrative Control Unit, which includes nearly 24-hour lockdown and complete isolation. Some prisons have solitary cells, but there is no indefinite solitary confinement in Minnesota. Likewise, Minnesota prisons track inmates who are members or associates of prison gangs (also known as Security Threat Groups or STGs), but do not segregate inmates from the general population due to their gang or STG status.

One of the minimum-security boot camp facilities is at MCF–Moose Lake, legislatively created in 1992 to provide early release to non-violent offenders who qualify. In addition, MCF–Willow River offers the Challenged Incarcerated Program (CIP) for adult males, an early release program option to those within 60 months of confinement release. The goals of the program are “(1) to punish and hold the offender accountable, (2) to protect the safety of the public, (3) to treat offenders who are chemically dependent, and (4) to prepare the offender for successful reintegration into society” (Minnesota Statutes §244.171).

Each Minnesota Correctional Facility (MCF) meets the standards established by the American Correctional Association (Minnesota Department of Corrections, 2014) and many incorporate MINNCOR Industries sites, which provide employment and training for offenders and manufacturing goods and services to all government agencies, private non-profits, K–12 schools, universities, cities, and counties.

Figure 4.4. Custody Levels in Minnesota (Minnesota DOC, 2015)

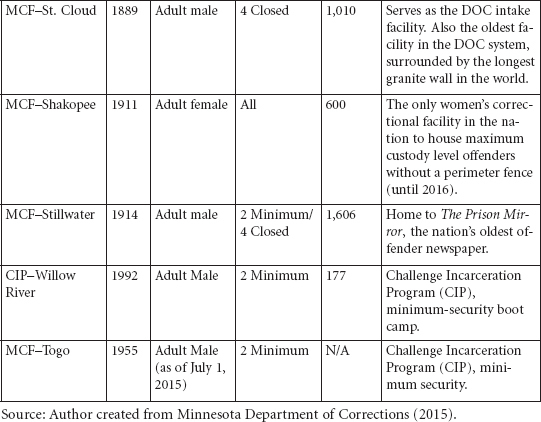

Table 4.4. Minnesota Correctional Facilities at a Glance

Women and Juvenile Correctional Facilities

In 1867, the House of Refuge first opened in Saint Paul to house young offenders. Technically the state's second prison after the Minnesota Territorial Prison in Stillwater, the House of Refuge was renamed to the Minnesota State Reform School in 1879, and it moved to Red Wing, Minnesota, in 1889. Later, in 1895, it was renamed the Minnesota State Training School and is now known as MCF–Red Wing. MCF–Red Wing is the only state-operated juvenile facility in Minnesota providing treatment, education, and transition services for males (Minnesota Department of Corrections, 2015). MCF–Red Wing's mission is to “Restore the offender, victim, and community; Promote public safety, offender accountability, and pro-social competency; Provide a premier continuum of services for juvenile offenders within a therapeutic environment.” Up until July 1, 2015, MCF–Togo offered a 21-day Wilderness Endeavors treatment option for girls and boys, a three-month residential treatment program for boys, and a chemical dependency program for boys, however, this was discontinued. Counties have separate facilities for housing juveniles awaiting court

dispositions/placement. For example, the Hennepin County Juvenile Detention Facility is a secure, 24-hour facility that holds 87 male and female juveniles for an average of seven days and provides programming that includes school (Hennepin County, 2015a). For more on juvenile corrections in Minnesota, see

Chapter Six

.

The state legislature created a reform school for girls in 1907. Thirteen years later, the state opened its first reformatory for women (Minnesota Department of Corrections, 2015). There is now one all-female prison in Minnesota, housing offenders of all levels. MCF–Shakopee is notable because it is the only facility in the United States to house maximum-security level prisoners without a fence. This, however, changes in 2016 when a fence will be added (Minnesota Department of Corrections, 2015).

Federal Prisons in Minnesota

Minnesota is home to two Federal Correctional Institutions (FCI), one Federal Prison Camp (FPC), and one Federal Medical Center (FMC). FCI–Sandstone is a minimum-level, dormitory-style facility for 1,350 male inmates. FCI–Waseca is a minimum-security facility for 1,000 female inmates. Programming in this facility provides an array of options, including GED preparatory courses, apprenticeship programs in landscape and HVAC, Silent No More for Change (for victims of domestic abuse), Prisoners Assisting with Support Dogs (PAWS), Chairs Ministry, and classes in a variety of subjects from yoga to history (Maranell, 2013). There is also FPC–Duluth which is a minimum-security federal prison camp for 800 inmates. In 2013, the prison made news headlines because two white-collar criminals escaped from the prison, only to be arrested less than a week later (Durkin, 2013). Lastly, Rochester is home to one of only six federal medical referral centers within the Federal Bureau of Prisons. FMC–Rochester houses 845 inmates (Federal Bureau of Prisons, 2015b). Any male inmate, regardless of classification, can be sent here for long-term medical or mental healthcare. On February 5, 2015, this facility made news headlines because it was releasing Minnesota's first offender to fight with Al-Shabaab in Somalia. Abdifatah Yusuf Isse was charged in 2007 with providing material support for terrorism abroad (Lyden, 2015). He ended up becoming a star witness and provided important insight to how Minnesota men were being radicalized for violent extremism (Yuen, 2015). For further discussion of federal corrections in Minnesota, see

Chapter Eight

.

Table 4.5. Federal Inmates' Rights and Responsibilities

Private Prisons

From 1996–2010, Minnesota housed inmates at Prairie Correctional Facility, a private medium-security 1,700-bed capacity facility owned and operated by Correction Corporation of America (CCA). CCA began in the early 1980s as a public–private partnership to provide correction services to states and has grown into the largest private-prison operator in the United States. CCA is a publicly traded company that employs 14,000 people in 21 states and lobbies to keep their prisons full (CCA, 2015). Focused on shareholder value, CCA controversially highlights how its prisons comprise a “unique investment opportunity” thanks to limited competition, “high recidivism” among prisoners, and the potential for “accelerated growth in inmate populations following the recession” (Taub, 2010).

Prairie Correctional Facility was located in Appleton, a small city in west-central Minnesota, on the South Dakota border. The prison was not equipped to hold offenders 60 years or older, offenders who had special medical or mental health needs, or those classified higher than medium custody (Duwe & Clark, 2013). At its height in 2008, Prairie Facility held 13% of the state's total prison population (Duwe & Clark, 2013). However, shortly after this, with the downturn in the economy, renovations to two state-run facilities, and slow growth in the Minnesota prison population (partially due to leveling out of the methamphetamine problem and multiple felony-level DWI convictions) the need to send inmates to this facility dwindled and other states did not send their inmates there, forcing the prison to shut down (Duwe & Clark, 2013; Steil, 2010). Prairie Correctional Facility closed its doors on February 2, 2010, and now sits vacant. The

closure had a huge economic impact on the small city, as tax revenues from the prison alone made up 60% of Appleton's budget (Steil, 2010).

Duwe and Clark (2013) examined the effectiveness of private prisons in reducing recidivism using a sample from Prairie Correctional Facility. Duwe and Clark (2013) compared 1,766 Minnesota prisoners from Prairie Correctional Facility to 7,769 prisoners released from other state-run facilities in Minnesota, controlling for a variety of variables. The focus was recidivism, defined as (1) re-arrest, (2) reconviction, (3) re-incarceration for a new sentence, or (4) revocation for a technical violation. Results showed that inmates housed in a private facility did not lead to improved recidivism rates. In fact, because this facility housed healthy and well-behaved inmates, the authors concluded, “private prisons produce slightly worse recidivism outcomes ... for the same amount of money” (Duwe & Clark, 2013, p.391).

Visitors in Prison

The Department of Corrections recognizes the importance of visitors as a way to help reduce recidivism, among other benefits, and therefore allows visitors to enter their facilities (Minnesota Department of Corrections, 2015). Any visitor 18 years of age or older must complete a visitor application and get approval prior to visiting the facility. There are two types of visits: (1)

contact

, which means the offender meets with the visitor in the visiting room; and (2)

no contact

, which means the offender and visitor are separated by glass and speak via phone/video. As in most states, there are no conjugal visits in Minnesota prisons. There also are strict rules surrounding a visit, controlling things like dress, contraband, seating arrangements, touching, child-care, photography, and other important considerations to maintain safety. In addition to family and friends who may visit, inmates can also receive visits from professionals such as lawyers, probation officers, and religious personnel.

One non-profit organization in Minnesota, Amicus, has a One-to-One Program that has been in existence for nearly half a century (Amicus, 2015). It is designed to give offenders an opportunity to develop positive relationships with people who live in the community who are matched to them by gender and characteristics that may be important to them, like religion or age. A volunteer agrees to meet with the offender for at least one year to hopefully develop skills, trust, and a feeling that someone cares. To date, over 8,000 inmates from four state facilities have been paired with a volunteer.

Employment in Prison and Jails

The Minnesota Department of Corrections is a major employer in the state. To become a correctional officer in a state prison, an applicant must apply for a six-week trainee program. To qualify, he/she must:

- be 18 (unless they work in juvenile facility, then it is 21 years of age),

- have a high school diploma or GED,

- have a valid driver's license,

- be eligible to possess a firearm, and

- pass a criminal history background check.

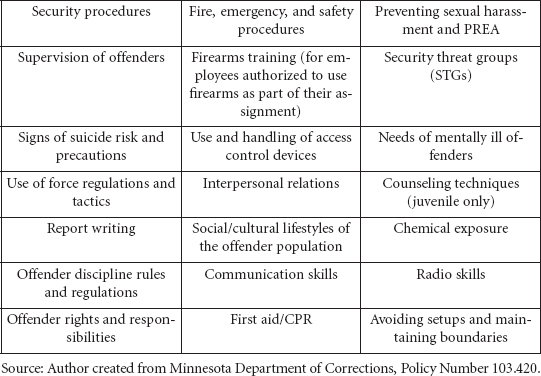

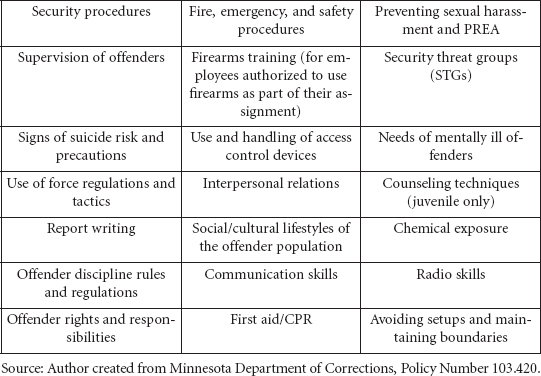

Throughout the training, the new recruit learns about a variety of topics, as listed in

Table 4.6

.

Table 4.6. Minimum Topics of Training New Correction Officers Receive during Their First Year

While in the trainee academy, the applicant is paid around $15 per hour. After completion of the program, the applicant becomes a correctional officer 1 for one year at a pay of around $16–$19 per hour and then is eligible for promotion to correction officer 2, with a pay range of around $18–$26 per hour (Minnesota Department of Corrections, 2015). The growth trajectory after

this is one of a supervisory or investigative capacity, including positions as a correction officer 3, caseworker, corrections captain, and corrections lieutenant (Minnesota Department of Corrections, 2015). The captain (also known as the watch commander) is a senior-level management position and in the absence of the warden, the captain may serve as the officer in charge of the institution. The Commission of Corrections appoints the warden. In addition to the correction officers and their supervisors, the DOC employs individuals with a variety of other skill sets, which includes such professions as teachers, nurses, accountants, counselors, and therapists.

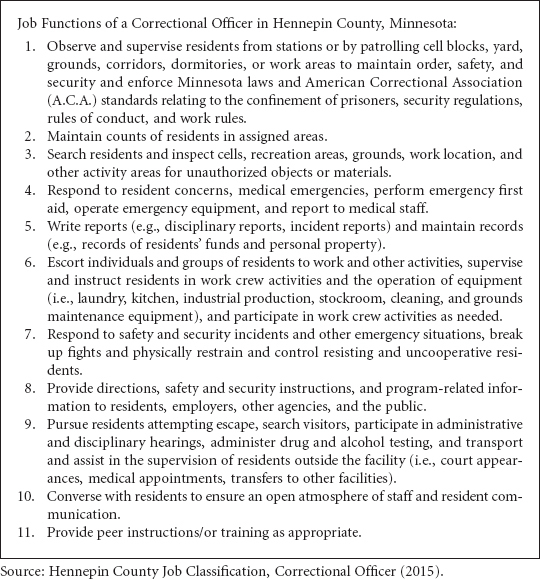

Figure 4.5. Work Duties of a Corrections Officer

In looking at county-level employment in the jails, qualification requirements may vary. For example, to be a correctional officer in the largest county in Minnesota, Hennepin, an applicant must have two years of college/vocational training, military experience, or two years of experience in criminal justice. The salary is approximately $18–$29 per hour (Hennepin County, 2015b). The duties of a correctional officer are found in

Figure 4.5

. A senior correctional officer requires a bachelor's degree or three years of experience. The salary range for this position is approximately $19–$31 per hour (Hennepin County, 2015b).

Community Corrections

Community corrections involve the supervision of offenders in the community. The most common types include probation and parole.

Probation and Parole

Probation and parole are both alternatives to incarceration. As defined by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (2015), probation is “a court-ordered period of correctional supervision in the community, generally as an alternative to incarceration. In some cases, probation can be a combined sentence of incarceration followed by a period of community supervision.” Parole is defined as “a period of conditional supervised release in the community following a prison term. It includes parolees released through discretionary or mandatory supervised release from prison, those released through other types of post-custody conditional supervision, and those sentenced to a term of supervised release.” In Minnesota, the term “parole” is synonymous with supervised release.

Nationally, one in 51 people, or 4.75 million offenders, were under some form of community supervision in 2013, which includes probation, parole, or other post-prison supervision (Herbeerman & Bonczar, 2015). Probationers made up a vast majority of these at 82% or 3.9 million offenders. As previously noted, the rate of individuals on probation in Minnesota significantly exceeds the national average. Minnesota's probation population is sixth highest in the country at 2,446 per 100,000 people. The national average is 1,479 per 100,000, with the lowest rate in New Hampshire (379 per 100,000) and highest rate in Georgia (6,829 per 100,000) (National Institute of Corrections, 2015). Women make up approximately 25% of the probation population (Glaze & Kaeble, 2014).

State agents and county probation officers supervise probationers. This is dependent on the county. Some counties are part of the Community Corrections

Act. The Community Corrections Act (CCA) was enacted in 1973 to provide more community corrections service by the reallocation of corrections resources. This came about because of (1) lack of effective public protection, (2) high cost of state institutionalization, (3) duplication of services and their delivery and, (4) inappropriate correctional supervision (Minnesota Department of Corrections, 1973). Any county with a population greater than 30,000 can be part of the CCA. A little less than half (37) of all the counties in Minnesota participate (Minnesota Department of Corrections, 2014). Twenty-eight counties utilize state probation officers, and the remaining 27 utilize both county and state probation agents (generally divided by level of offense, with state taking the more serious adult offenders and the county taking the juveniles and the adult non-felons).

As for parolees, Minnesota has 144 per 100,000, in comparison with a national average of 267. Maine ranks the lowest at 2 per 100,000 and Pennsylvania the highest at 1,029 per 100,000 (National Institute of Corrections, 2015). There is no federal parole for inmates who have committed a crime after 1987 because of the Sentencing Reform Act. However, there are offenders who were sentenced prior to this date who are still eligible.

The Minnesota Department of Corrections supervises 18,456 of the approximately 122,000 offenders statewide. In the 1980s, Minnesota instituted a series of reforms to the state's correctional system, including

Determinant Sentencing

, which abolished the parole board and time off for good behavior. As a result of Determinate Sentencing, most offenders now serve two thirds of their prison sentence behind bars and the remaining third on supervised release. However, some crimes, like felony-level DWI, impose a mandatory five-year conditional release if the offender is sentenced to prison for first-degree DWI, instead of just one third of the sentence. If a violation occurs, the offender can go back to prison to serve out the remaining one third of the original sentence (Cleary & Pirius, 2008, p.8). In turn, the Minnesota Department of Corrections supervises two types of offenders:

- Felony offenders who have served the mandatory two-thirds of their prison sentence who have been released from prison; and

- Probationers who were not committed to the custody of the Commissioner of Corrections but reside in counties that do not find it practical to operate a local supervision program.

The crimes which the offender committed to bring them to a state agent are drug related in slightly over one fifth of cases, followed closely behind by DWI and property, with person crimes not too far behind, as provided in

Figure 4.6

.

Figure 4.6. Types of Crimes Because of Which Offenders Were Supervised by Minnesota Department of Corrections Agents in 2013

The Department of Corrections also manages three community offender programs.

-

Sentencing to Service (STS).

This program, developed in 1986, is available only to non-violent offenders who work for free on community improvement projects that could benefit a city, county, township, school district, state, and/or non-profit organization, to include such things as picking up litter, cleaning storm drains, trail development, and river cleanup. It is estimated that the value of the projects STS crews work on is equal to around $5.5 million per year (Minnesota Department of Corrections, 2011). It should also be noted that some counties operate their own STS for both adult and juvenile offenders, which in some cases allows them to work off court fines and fees.

-

Institution/Community Work Crew (ICWC) Program

. This program developed in 1995 to pay offenders a small wage ($1.50/hour) to be used to pay restitution, family support, and a fund for victims while they work in an organized supervised crew on such things as construction, land restoration, and forestry work (Minnesota Department of Corrections, 2013b).

-

Work Release

. This program was legislatively created in 1967. It provides close supervision while offenders work full time. Because they are earning a salary they must pay for housing costs, as well as restitution, fines, and other fees (Minnesota Department of Corrections,

2014b). It should also be noted that at the jail level, Minnesota's facilities were listed as the second highest (behind North Dakota) for having a work release or prelease function (Stephan & Walsh, 2011).

When an offender is on probation he/she must obey certain conditions. Violation of any of the conditions could mean a warrant for his/her arrest and subsequent probation revocation. Conditions of probation generally include such things as reporting to a probation officer on a regular basis, not committing any type of crime in any jurisdiction, not possessing a firearm, not using any illegal drugs, and random drug testing. All felony offenders are barred from voting and leaving the state of Minnesota without prior permission. Those on supervised release or on probation are expected to submit to warrantless searches, without probable cause. Discretionary conditions are specific to the offender and can include a range of requirements like completing chemical dependency assessment and treatment, obtaining and maintaining employment, completing domestic violence programing, attending therapy, or attending anger management or parenting classes. They may be required to pay restitution, or child support, stay away from certain individuals or locations, or have no contact with the victims or co-defendants. Probation officers are also allowed to impose intermediate sanctions without going to a court hearing if there are probation violations. For example, a probation officer can require his/her probationer to participate in a Sentence to Serve (STS) Program up to a certain period of time. Whether the violation occurred in a CCA county also dictates the amount of power a probation officer has in regard to imposing various types of intermediate sanctions.

Intensive Supervised Release (ISR)

Minnesota's Intensive Supervision Program was established by the legislature in 1990 (Minnesota Statutes §244.12–244.15). The program requires that certain high-risk offenders be identified while in prison, and that those offenders be placed on intensive supervised release (ISR) upon release from prison. Offenders remain on ISR until they successfully complete the program or until they reach expiration of their sentence. ISR elements include house arrest, electronic monitoring (which may include GPS monitoring, which costs an additional $8–$13 per day, per offender), curfews, random drug/alcohol testing, unannounced residential and work visits by the supervising agent, a mandatory 40 hours per week of work/education, payment of supervision fees, and restitution to victims. Offenders are also required to comply with any special conditions of their release, which may include attending sex offender treatment,

Alcoholics Anonymous, and/or anger management classes. ISR consists of six phases, but only level-three predatory offenders are required to complete phases five and six (see Minnesota Department of Corrections, 2012b).

Employment as a Probation Officer

To work as a probation officer (also referred to as corrections agent) for the state of Minnesota, an applicant must meet the following criteria: bachelor's degree in a criminal justice related field and the completion of either (1) a 400-hour internship, (2) two years of experience as a correctional officer/supervisor of Sentence to Serve crew leader, or (3) 6 months of professional level experience as a case manager. It is important to note that in Minnesota, a probation officer is not a licensed peace officer. In other states probation officers are certified by the state's Peace Officer Standards and Training Board. Among other things, this means probation officers in Minnesota are not armed. The salary range is $19 to $27 per hour (Department of Corrections, 2014). The requirements to work in a county as a probation officer are county-specific. The largest county in Minnesota, Hennepin, requires probation agents to have a master's degree in a criminal justice related field with an internship or a bachelor's degree with one year of paid/volunteer approved related experience. The salary range is $18 to $31 per hour for a probation officer, with senior and career probation officers making more (Hennepin County, 2015b).

The job duties of a state probation officer as outlined by the Department of Corrections (2014) include things like providing investigative services to the court, having releasing authority and supervisory and/or referral services to offenders, facilitating law abiding behavior, completing assessments of offenders to determine appropriate levels of supervision, preparing case plans, monitoring offenders in compliance with probation, completing progress reports and detention orders, and testifying in court as needed. If a defendant pleads guilty or is found guilty at trial, for example, a probation officer may be assigned to conduct an investigation before sentencing (known as a pre-sentence investigation or PSI). The probation officer gathers information about the possible sentence for the crime and additional information about the defendant. They may also gather information about the impact of the crime from the victim. The probation officer then gives a report to the judge with recommendations about sentencing.

The job duties of a county probation officer are essentially the same as outlined in

Figure 4.7

.

Figure 4.7. Job Duties of a Probation Officer

Other Issues in Corrections

Cost of Corrections

Like elsewhere, the cost of corrections in Minnesota is not cheap. Minnesota Statutes §241.018 requires annual reporting of the average department-wide cost per diem of incarcerating inmates in state, county, and regional facilities. In 2013, the general fund budget for the Minnesota Department of Corrections was $481,470,000 (Minnesota Department of Corrections, 2013). In 2010, Minnesota spent an average of $41,364 per inmate. Compared to nationally, this is almost $10,000 more per inmate, with the average cost being $31,286 and more than in the neighboring states of Wisconsin at $37,944, Iowa at $32,925, and North Dakota at $39,271 (Vera Institute, 2012). Minnesota has the 14th highest cost per inmate in the U.S., with Kentucky the lowest at $14,603 and New York the highest at $60,076 (National Institute of Corrections, 2015). These costs not only include the direct cost of the prisons, but also expenditures like administrative costs, employee benefits and taxes, pension contributions, retiree healthcare contributions, capital costs, judgment claims, hospital services, underfunded pensions, and education and training (Vera Institute, 2012).

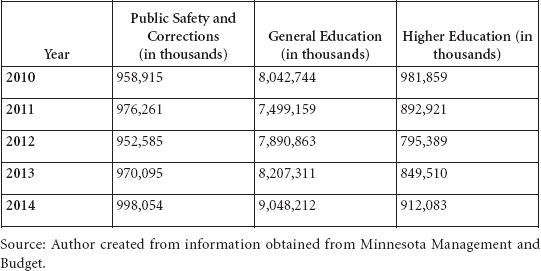

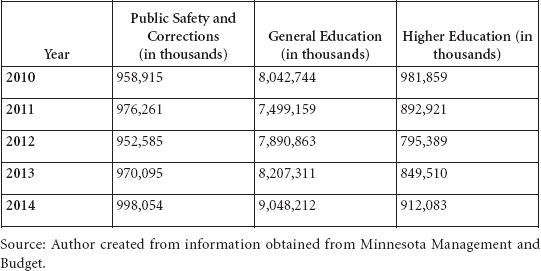

In reviewing the state's comprehensive financial report from 2010–2014 as a whole, the spending on public safety and corrections is slightly increasing, however, when compared to expenditures in general education, the increase is modest. Minnesota spends significantly more money on general education than on corrections and public safety, however, when looking at higher education in particular, the expenditures are slightly greater for public safety and corrections.

Table 4.7. Expenditures in Minnesota from 2010–2014 (in U.S. dollars)

One factor that must be recognized when looking at the costs of prison is healthcare costs. The Pew Chartable Trust (2014) highlights that the three main reasons for growing health expenses are: “(1) aging inmate population, (2) prevalence of infectious and chronic diseases, mental illness, and substance abuse among inmates, many of whom enter prison with these problems, and (3) challenges inherent in delivering health care in prisons, such as distance from hospitals and other providers.” Prisoners have a constitutionally guaranteed right to healthcare, therefore, they must be treated. This fact was very publically highlighted when an escaped prisoner, Clarence Moore, who had been on the run for 39 years, turned himself in to the local authorities in April 2015 because he needed healthcare (Johnson, 2015). The ACLU (2012) estimates that releasing elderly prisoners could save an average of $66,294 per inmate. Furthermore, it estimates the cost to incarcerate inmates 50 or more years old, who are relatively low-risk and who total fewer than 250,000 inmates in the U.S., equals $16 billion dollars. Some Minnesota inmates have medical costs that have exceeded $1 million (McEnroe, 2012).

Support Programs in Prisons and Jails

Minnesota prisons have been offering a multitude of programs to try and reduce recidivism, as well as help offenders with education, employment, and substance abuse issues. In 2013, Duwe provided a summary report of evaluations done on various prison programs within Minnesota's Department of Corrections. Results showed programs offered improved public safety, helped with post-release employment, and/or reduced costs to taxpayers. These programs include: (1) EMPLOY, (2) work-release, (3) educational degrees, (4) Minnesota Comprehensive Offender Re-entry Plan, (5) Interchange Freedom Initiative, (6) Minnesota Circles of Support and Accountability, (7) Challenge Incarcerated Program, (8) chemical dependency treatment, (9) sex offender treatment programs, and (10) Affordable Homes Program. After reviewing all of these evaluations, Duwe highlights common threads to include: programs that provided for pro-social support had a positive effect on reducing recidivism; programs that helped with criminal thinking patterns reduced recidivism; programs that targeted chemical abuse reduced recidivism; employment programs yielded higher employment; and that continuum of care from prison to the community was important (Duwe, 2013). The programs highlighted are a sampling of some of the programs available in the DOC, but the list is not exhaustive. Thinking for a Change, which is a cognitive skills building class, Read to Me, which allows inmates to record themselves reading a book that can then be given to their children, and Minnesota Prison

Writing Workshop, which provides all kinds of opportunities for writing in various styles and publishes a literary journal, are other examples.

Support Programs in the Community

There are many non-profit organizations in Minnesota that work directly with offenders while in prison, during their re-entry period, and/or after care to try and help reduce the likelihood of recidivism. Employment is a major factor in helping offenders not recidivate and as such, there are community organizations and groups that work towards this end. For example, the Second Chance Coalition is a partnership of organizations that “advocate for fair and responsible laws, policies, and practices that allow those who have committed crimes to redeem themselves, fully support themselves and their families, and contribute to their communities to their full potential” (Second Chance Coalition, 2015). Some of the recent initiatives they are working on include trying to restore voting privileges, reduce the severity of drug offenses, reduce prison gerrymandering, and rename the crime of “terroristic threats.”

Another organization that helps offenders secure employment is Goodwill Easter Seals of Minnesota. Their reentry services start while offenders are incarcerated and continue after release to include such things as advocacy, community resources, employer relationships and education, an employment readiness program, individual case management, mental health/cognitive skills training, mentoring, and a motivational job coach (Easter Seals MN, 2015). Through intensive case management, support with job skills training, support in employment, housing, transportation, and pro-social activities, SOAR's Community Offender Re-entry Program (CORP) helps offenders transition back into the community. In 2012, SOAR worked with 592 offenders in the community on employment and job skills training and provided reentry services to 85 offenders to include services related to sobriety, family relationships, financial responsibility, and pro-social relationships. SOAR participants had a 16% recidivism rate (SOAR Career Solutions, 2012). Amicus is another organization that has a program, Amicus Reconnect, which helps anyone with a criminal record to try and work through the challenges that comes with having a criminal past (Amicus, 2015). They also administer Sisters Helping Sisters to support women prior to and after release to build confidence, have a positive outlook, and live a healthy lifestyle. As with programs inside the prison, the above is sampling of the many organizations and programs that work with offenders in the community.

Professional Organizations

There are several professional organizations that directly assist those individuals who work in a corrections capacity. Some of these organizations and their related function include the following:

-

Minnesota Community Corrections Association

's purpose is to promote “professionalism and collaboration among individuals and agencies working within community corrections.”

-

Minnesota Association of County Probationers

' purpose is to “support the preservation and expansion of professional probation and adjunctive services to the courts of Minnesota ...”

-

Minnesota Restorative Services Coalition

's purpose is to “promote restorative philosophy and quality restorative services for individuals, communities, and organizations.”

-

Minnesota Association of Community Corrections Act Counties

has several main functions including (1) providing a forum to exchange information and resources among the 32 Act Counties, (2) developing policy recommendations, and (3) coordinating and facilitating interaction with the Department of Corrections.

- The Minnesota Association of Pretrial Services

' purpose is to “create a more safe and just criminal justice system by providing quality training to our members, promoting information to improve pretrial programs and promoting the importance of pretrial services in Minnesota.”

Pardons/Commutation/Pardon Extraordinary/Expungement

In Minnesota, pardons/commutation/pardon extraordinary can be granted under Minnesota Statutes §638.01 for any criminal offense. A board, consisting of the governor, the chief justice of the Supreme Court, and the attorney general meet two times a year to review applications. A

pardon

is defined as an “act of forgiveness that exempts the convicted person from the punishment imposed by the law.” A

commutation

is the “substitution of a lesser or different type of punishment for that imposed in the original sentence.” A

pardon extraordinary

is a statutory release. When one is granted, the consequences of criminal convictions are removed. The applicant is “no longer required to report the conviction, except in specific limited circumstances.” A convicted offender can apply after it has been ten years since the sentence expired for a violent offense and five years for any other crimes. The board cannot grant

these for federal crimes, crimes committed in other states, or crimes committed in foreign countries (Minnesota Department of Corrections, 2015b). As illustrated in

Table 4.8

, pardons or commutations are extremely rare occurrences and pardon/pardon extraordinary are granted on average in less than a third of the cases that applied. An

expungement

is when an offender requests his/her record to be sealed. The records are not destroyed and law enforcement agencies and other public officials can still access them in special cases. Expungements are made possible through Minnesota Statutes §609A.02 in specified situations such as for drug possession offenses or offenses committed while a juvenile, but tried as an adult. It is should also be noted there is an Innocence Project in Minnesota. They “represent people who were wrongfully convicted for crimes they did not commit, educate attorneys and criminal justice professionals on best practices, and work to reform the procedures that produce such unjust results” (Innocence Project, 2015). At a nationwide level, their efforts have helped over 325 people, serving an average of 13.5 years in prison for a crime they didn't commit, become free (Innocence Project, 2015). See

Chapter One

for an example of a case from Minnesota.

Table 4.8. Minnesota Board of Pardons Activities from 2009–2013

Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA)

In 2003, the Prison Rape Elimination Act took effect in order to eliminate sexual abuse in confinement. As part of this act, a National Standards document was developed to prevent, detect, and respond to prison rape, taking

effect in 2012. There are two separate standards: one for adult facilities and another for juvenile facilities (Department of Justice, 2012a; Department of Justice, 2012b). The National PREA Resource Center (2015) provides correctional personnel assistance with the implementation by outlining 12 essential components of these standards that the facilities must address. These include: (1) prevention planning, (2) responsive planning, (3) training and education, (4) screening for risk of sexual victimization and abusiveness, (5) reporting, (6) official response following an inmate/detainee/resident report, (7) investigations, (8) discipline, (9) medical and mental care, (10) data collection and review, (11) audits and state compliance, and (12) other issues including LGBTI and gender-nonconforming inmates and culture change.

The Minnesota Department of Corrections PREA Policy is 202.057 and it states:

All employees, contractors, and volunteers are expected to have a clear understanding that the Department strictly prohibits any type of sexual relationship with an individual under the Department's supervision, and considers such a relationship a breach of the employee code of conduct. These relationships will not be tolerated. Mandatory staff training and offender education is provided to convey the expectation. (Minnesota Department of Corrections, 2015c)

The Minnesota DOC has a zero tolerance policy on sexual misconduct. It provides inmates with an offender brochure outlining their rights and responsibilities. Each facility has a compliance manager and there is a coordinator that oversees the DOC to make sure it is in compliance with PREA. Jails also must be in compliance with PREA, and like the state facilities, are audited to make sure they meet PREA standards.

Conclusion

While a review of the entire corrections system in Minnesota cannot be accomplished in one chapter, this chapter provided a survey of some of the statistics, structure, programs, employment, history, and legislation that is part of the landscape of corrections. Corrections is multifaceted and an important part of what makes up the criminal justice system. The ultimate goal, of course, is to have less need for corrections, because that would be an indication there is less crime.

Key Terms

Advisory Groups in Corrections

Amicus

Ban the Box

Commissioner of Corrections

Community Corrections Act

Commutation

Correction Officer

Determinate Sentencing

Disproportionate Minority Contact Act

Doula Services

Expungement

Innocence Project

Intermediate Sanctions

Jail

Pardon

Parole/Supervised Release

PREA

Prison

Prison Costs

Private Prisons

Programming in Prisons

Programming in the Community

Re-entry Programs

Religion in Prison

Second Chance Coalition

Sentencing to Serve

Transition from Jail to Community (TJC) Initiative

Work Crew

Work Release

Discussion Questions

- What are the benefits of supervised release over incarceration?

- What do you think the benefits/drawbacks are of private prisons?

- What services do you think are critical for offenders to have available to them as they re-enter society to help reduce recidivism? Why?

- Do you think states and the federal government should release older (age 65 and up) offenders into the community? If yes, at what age and for what type of offenses?

- Are pardons a good thing for the government to offer? Why/why not?

- Do you think expungement of records is a good practice? In what cases should they be used? Should it be automatic or an application process?

- Do you think prisoners should earn money while working in prison? What are some arguments for and arguments against? How much should they be allowed to earn?

- What do you think about infants in prison? Should mothers who give birth while in prison be allowed to keep their newborn in the facility? If yes, for how long?

- What do you think about allowing religious head coverings and other religious items in prison and jail facilities? Do you think more should be done to help inmates to practice their religious beliefs?

- Do you support Ban the Box? Why or why not?

Selected Webpages

References

Alexander, M. (2012).

The new Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness

. New York: The New Press.

Beccaria, C. ([1764] 1963).

On crimes and punishments

. Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill.

Duwe, G., & Clark, V. (2103). The effects of private prison confinement on offender recidivism: Evidence from Minnesota.

Criminal Justice Review

, 38(3), 375–394.

Glaze, L., & Kaeble, D. (2014). Correctional populations in the United States, 2013. U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau Statistics. NCJ 248479.

Holt v. Hobbs. 574 US ____ (2015).

Lee v. Weisman, (1992). 505 U.S. 577, 578, 112 S. Ct. 2649, 2655, 120 L. Ed. 2d 467, 480.

Minnesota Association of Community Corrections Act Counties. (2015). Retrieved from

http://www.maccac.org

Skarbek, D. (2014).

The social order of the underworld: How prison gangs govern the American penal system

. New York: Oxford University Press.

Stafford, M. C. & Warr, M. (1993). A reconceptualization of general and specific deterrence.

Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency

, 30, 123–135.

Stephan, J., & Walsh, G. (2011). Census of jail facilities, 2006. Bureau of Justice Statistics. NCJ 230188.

Stuntz, W. (2011).

The collapse of American criminal justice

. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sykes, G. (1958).

The society of captives: A study of a maximum security prison

. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Travis, J., Western, B., & Redburn, S. (2014).

The growth of incarceration in the United States: Exploring causes and consequences.

Washington D.C.: National Research Council.

von Hirsch, A. (1976).

Doing justice: The choice of punishments

. New York: Hill and Wang.

Zimring, F. E., & Hawking, G. (1995).

Incapacitation: Penal confinement and the restraint of crime

. Oxford: Oxford University Press.