“The Black Hats” at Gettysburg, July 1, 1863

THE 19TH INDIANA MARCHED TO PENNSYLVANIA IN 1863 AS A VETERAN regiment in the famous Iron Brigade. Along with the 2nd, 6th, and 7th Wisconsin, and later the 24th Michigan, the Hoosiers saw action at Gainesville, Second Bull Run, South Mountain, Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville. None of the fighting, the veterans said later, prepared them for what they called the “four long hours” of July 1, 1863, at Gettysburg, where the Iron Brigade was all but wrecked.

The brigade ran into the infantry fighting at midmorning on a hot day and enjoyed early success in the open fields northwest of Gettysburg, knocking back two Confederate brigades. “It’s those damned Black Hats!” the Confederates called on seeing the western men and their famous headgear. By afternoon, however, the Confederates were advancing in heavy lines to seize the town. The Iron Brigade was strung out in defensive position above Willoughby Run on McPherson’s Ridge. The 19th Indiana was on the left with the 24th Michigan, 7th Wisconsin, and 2nd Wisconsin, extending the line to the north. The 6th Wisconsin was detached and posted elsewhere. The Union line was outnumbered and overlapped.

By midafternoon, the outnumbered Hoosiers were fighting for their lives, bending back under a heavy flank fire, and disappearing “like dew before the morning sun.” The 19th Indiana carried two flags—a blue regimental flag presented by the ladies of Indianapolis and a national color flag requisitioned when a complementary national flag from 1861 was retired. Sergeant Burlington Cunningham, already once wounded, was carrying the national banner when hit a second time. Nearby, Color Corporal Abe Buckles also went down. Lieutenant Colonel William Dudley grabbed the national flag and was shot in the right shin—a wound that would cost him his leg. In the noise and smoke, Sergeant Major Asa Blanchard came up to take the flag, saying: “Colonel, you shouldn’t have done this. That was my duty. I shall never forgive myself for letting you touch that flag.” Eight Indiana color bearers were now down and half the regiment killed or wounded.

Under heavy fire from two advancing Confederate brigades, the Indiana flag—now in the hands of another man—fell yet again. Before Blanchard could reach it, however, Color Corporal David Phipps, who was carrying the Indiana regimental, scooped up the fallen national and was waving it with one hand. Then Phipps was wounded and fell on both flags. “The flag is down!” someone shouted and Captain William W. Macy yelled to a nearby private to “Go and get it!”

“Go to hell, I won’t do it,” said the soldier.

Macy, Lieutenant Crockett East, and Color Corporal Burr Clifford rolled Phipps off the flags. Aware the bright silk was attracting bullets, East furled the banner and got it into its case and was trying to wrap the tassels when he was shot and killed. Macy and Clifford finally got the two flags in the cases only to be confronted by an angry Blanchard, who demanded the flags. “No, there’s been enough men shot down with it,” said Macy, but Blanchard appealed to Colonel Samuel J. Williams and the colonel told Macy to turn over the flags. In a swirl of bullets, Blanchard stubbornly unfurled the national colors and tied the case around his waist, calling in a loud voice, “Rally boys!” He was waving it when a bullet severed an artery in his thigh and he fell in a gush of blood, dying almost immediately. Clifford then picked up the national color and made a run for the town and safety.

The Iron Brigade line was soon swept away and the surviving Black Hats made their way through Gettysburg to the Federal rally point on Cemetery Hill. Their stout fighting delayed the Confederates long enough to allow Union forces to secure the defensive positions that would win the battle over the next two days. But the holding action came at terrible cost. The Iron Brigade marched to Gettysburg with 1,883 men and by dusk only 671 rallied around the flags. In the 19th Indiana, of the 288 carried into the fight, only 78 were still in ranks—a loss of almost 73 percent.

Hardee hat worn by Sergeant Jason Lewis of Company A, 46th Massachusetts Volunteers. In place of the regulation insignia, it has a silvered company letter over the regimental number. Lewis, who mustered on October 15, 1862, served mostly on the North Carolina coast until he was mustered out in July 1863. This hat shows signs of heavy use. JAN GORDON COLLECTION

This state-issue forage cap was worn by John H. Blanding of Company D of the 30th Wisconsin Volunteers. Blanding enrolled on August 21, 1862, and worked his way through the ranks to sergeant. He was discharged for disability on February 7, 1863. In addition to the company letter and regiment numbers, this cap features a rare state “panel” badge (often referred to by collectors as a “veteran” badge). MICHAEL CUNNINGHAM COLLECTION

Infantry uniform coat worn by Edgar S. Yergason of the 22nd Connecticut Volunteers. Made by Charles G. Day & Co. of Hartford, Connecticut, as part of their U.S. contract for 14,000 coats dated August 29, 1862. It varies from the regulation garment by lacking the light blue welt along the cuff opening. DON TROIANI COLLECTION

Corporal’s dress coat worn by Frank Fitz of the 44th Massachusetts Volunteers. The 44th Regiment was a “white glove” regiment with all of their uniforms being special order, not the usual government contract goods. The material of the coats was finer and the sleeves stylishly cut wide in the elbow like that of an officer. The linings were also of a higher-grade material with even the skirts fully lined, unlike those of the issue item. DON TROIANI COLLECTION

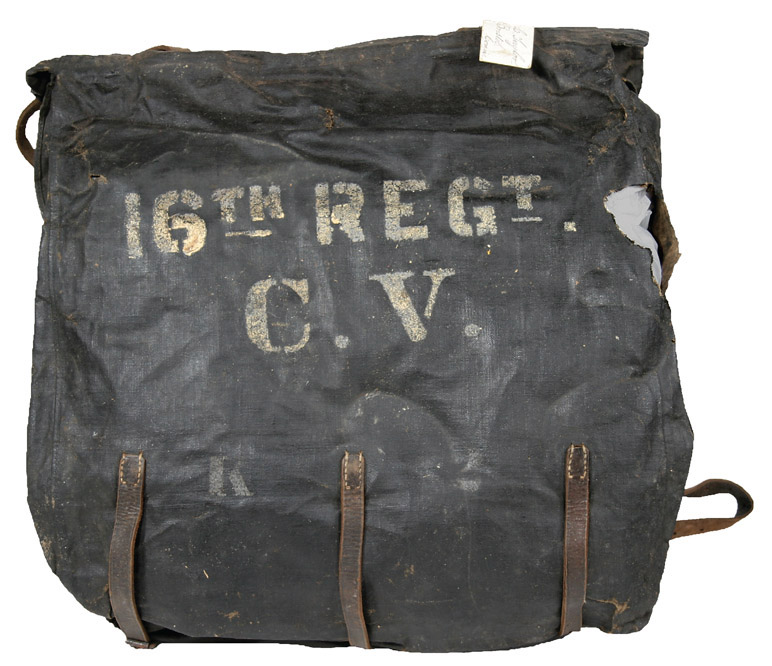

Soft painted knapsack worn by a soldier of the 16th Connecticut Volunteers. Many units painted their designations on the back of the knapsacks, particularly in the first half of the war. DON TROIANI COLLECTION

A pair of U.S. Army enlisted man’s gray woolen knit socks given to the Danish government in 1857 as a gift. TOJHUSMUSEET MUSEUM, DENMARK, MICHAEL CUNNINGHAM PHOTO

A classic pair of U.S. Army–issue shoes commonly known as brogans. Made by scores of contractors, the brogans come in a number of variations. NELSONIAN INSTITUTE

A pair of imported French chasseur trousers of what was called at the time dark sky-blue kersey. These were originally issued with the French chasseur uniforms to the 18th Massachusetts and 62nd and 83rd Pennsylvania Regiments. The remaining stocks were issued out to the 155th Pennsylvania late in the war when that regiment was converted to a Zouave uniform. Some went to assorted units such as military bands. DON TROIANI COLLECTION

Two spools of U.S. Army–issue thread found in the knapsack of a soldier of the 16th Connecticut Regiment. DON TROIANI COLLECTION