Wayne Robins, New Musical Express,

23 February 1974

NOTE: Wayne’s piece, originally published in Creem, has been reworked in order to edit out substantial quotes from Steely Dan lyrics.

I’m sitting drinking Campari in the Angry Squire on Seventh Avenue on a dull, sultry Sunday night in Greenwich Village, watching the sippers and swallowers drift through a brew or two, then buzz out somewhere else.

A swarthy New York street cowboy saunters in, locking his Honda bike to the hitching post outside. He orders a Whitbread Ale (on tap), takes a poke, then moves to the juke. A song about a guy with ‘murder in his eyes’: it’s ‘Only a Fool Would Say That’, the B-side of the Steely Dan hit ‘Reelin’ in the Years’.

I nodded to the guy in the cowboy hat, but he didn’t see me. That was cool. But when another obscure Steely Dan B-side, ‘Fire In The Hole’ (the flip of ‘Dirty Work’), came on under his quarter, I decided to walk over and ask him what his motives were.

But before ‘Reelin’ In The Years’ went through its remarkable Elliott Randall guitar solo, the urban cowboy was out of the door. To me it kind of indicates where the Steely Dan cult is at: found often in unlikely places, following no discernible pattern except walking slow, drinking alone and moving swiftly through the night. It’s strange that a band with such an unfashionably enigmatic lyric sense, rich in a bittersweet vision of people and places both familiar and remote, would turn out to be a Top 40 hit act rather than a ‘critic’s band’. Especially considering they took their name from a dildo in William Burroughs’ Naked Lunch.

‘We always felt we would be a hit with the critics, if not with the public,’ muses Walter Becker, who with Donald Fagen makes up the songwriting nucleus of the Dan. ‘But rock’n’roll reviewers adapt to the times and, if the times happen to be unsophisticated, that’s what happens.’

Whether or not you agree with Becker, it’s true that the Dan are indeed sophisticated for these times. Musically, they combine deceptively simple Latin-Caribbean rock’n’roll riffs with melodies that can buy a thrill. But Steely Dan go much deeper than that, especially if you’re one of the six hundred or so people on the planet who each year attended funky and fragmented Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, in the late ’60s, where Fagen, Becker, and myself got certain parts of their schoolin’.

I recognised Fagen and Becker as fellow Bardians when I saw Steely Dan perform in 1972 as the guest of Robert Christgau. I had been introduced to the Dean of American Rock Critics at a lavish CBS Records party for West, Bruce & Laing at Rockefeller Center’s Rainbow Room. Christgau was at the time the rock critic for the massive Long Island, NY, newspaper Newsday, which had been my hometown paper growing up. He invited me to come along to Westbury Music Fair the following week, where Steely Dan, still the original aggregation with David Palmer as the putative lead singer, was the opening act. For Cheech & Chong.

I had seen Becker and Fagen around campus, most likely in the coffee shop, but never spoke to them beyond a brotherly ‘What’s up?’

The kids who went to Bard were generally of the same breed that went to any of the schools with which it’s been associated; hotbeds of social permissiveness and intellectual stimulation like Goddard, Antioch, Franconia and Reed.

Fagen and Becker began playing together at Bard. ‘Whenever there was a social function that demanded a cheap rhythm section, we were there,’ says Becker, who looks the bespectacled silent type – with or without his bass – but is really verbal and articulate. ‘Actually, there were two branches – the New York branch, and the Boston branch.’

Out of the Boston branch came Jeff ‘Skunk’ Baxter, erstwhile guitar and steel player, who was once a member of Bosstown sound pacesetters Ultimate Spinach.

‘I joined the band [Spinach] after their first guitar player got too psychedelic,’ says Skunk.

‘You mean 13th Floor Elevators psychedelic or dangerous psychedelic?’

‘No, this was different. This was real drugs. Lots of drugs.’

Skunk doesn’t want to talk anymore about Ultimate Spinach. He’s far too modest about their place in the rock pantheon.

During the interview, which took place at a rehearsal studio on Yucca Street in Hollywood, a few blocks off Sunset and Vine, we kept coming back to Bard. References to the school run through much of Steely Dan’s two albums. ‘Reelin’ In The Years’ is probably the best song ever written about the pseudo-poetic, preppie/hippie self-consciousness that dominated Bard and other joints of its kind in the late ’60s.

On the second album, Countdown To Ecstasy, there’s even a tune called ‘My Old School’. It is possible that in part it chronicles one of the annual Bard busts, in which the Dutchess County Police, under Sheriff Quinlan and an assistant DA named G. Gordon Liddy, would deputise every townie bowling at the 9-G Lanes and carry off ten to twenty per cent of the student body.

There were plenty of fitting human subjects for songs at Bard, people who left themselves permanently imprinted in the Bard collective unconscious. Dudes like Marcus Aurelius Greenberg, an R&B oldies fanatic, greaser and part-time (most of the time) junkie, who was once roused out of a serious smack’n’Seconal OD at 3.30 a.m. to write a twenty-page paper on Nabokov that was due the next morning. (He got an A minus.)

Of course, Steely Dan aren’t the first ones to write specifically about Bard in their music. When we were there, old Bardians swore that the busted pump down the road near Adolph’s bar (legendary Bard hangout) didn’t work ‘’cause the vandals took the handles’, and that Dylan wrote that song (‘Subterranean Homesick Blues’) on the walls of the graffiti-famed Potter dorm shit-stalls. I take this to be myth.

After Bard, Steelies Fagen and Becker made their way back to New York. They did an album on Spark Records under the name The Original Soundtrack. The album itself was a soundtrack, for the famed Zalman King movie You’ve Got to Walk It Like You Talk It (or You’ll Lose That Beat). It featured a really killer Fagen and Becker song called ‘Dog Eat Dog’, one of those early attempts at pop tunes that was just too odd for Top 40 radio.

After the soundtrack (the movie lasted in release about fifteen minutes), Fagen, Becker and Denny Dias formed a rehearsal band that played in Denny’s basement in Hicksville, Long Island. The drummer happened to be Jay & the Americans’ road drummer, and all of them soon found themselves on the road with … Jay & the Americans.

‘Mostly it was playing sleazy little night clubs in Queens and the Bronx,’ recalls Walter Becker. ‘It was a very compact operation … it also paid the rent.’

After a year or so, the circuit began to get tedious. Fagen and Becker – and Denny and Skunk – were sort of hanging around when an old friend, Gary Katz, became a staff producer at ABC-Dunhill in Los Angeles. Katz got Fagen and Becker jobs as staff writers at Dunhill, and that’s where the modern Steely Dan saga takes off.

‘They gave us somebody else’s office with a terrible piano in it,’ said Walter, ‘and we started banging out the hits. It didn’t take us too long to find out that it wasn’t going to work, because the “hits” we were coming up with were really too weird or too cheesy for anyone to record.’

‘A staff writer is supposed to be a researcher of radio as well as a creative person,’ adds Donald. ‘It’s essentially imitating whatever you hear on the radio and putting it out eight or ten months later.’

The first Steely Dan album, Can’t Buy A Thrill, was recorded in June 1972, after six fruitless months on the song squad. Both the Dan’s hit singles (‘Do It Again’ and ‘Reelin’ In The Years’) are here, as well as a few songs that could’ve been hits if the band were greedy. LA songs like ‘Midnite Cruiser’ and ‘Turn That Heartbeat Over Again’. New York nostalgia moves like ‘Brooklyn (Owes the Charmer Under Me)’ and the brilliantly pop-ish ‘Dirty Work’, which Birtha are trying to break out with.

A few personal changes have ensued. Vocalist David Palmer, who sang on neither of the band’s hits, is gone. To add spice to the vocals and the visual situation (the band don’t exactly look like they just jumped out of Modern Romance magazine), two foxy lady vocalists have been added. Their names are either Porky and Bucky, or Chip and Dale, or Gloria Granola and Jenny Soule.

The second album, Countdown to Ecstasy, was my most played album throughout the past summer, and remains a steady favourite. The sound is deep and well-strung with patterns constantly shifting under the melodies and rhythm.

The scenarios are elliptical. There are women in cages in ‘Razor Boy’, which always reminds me of David Bowie’s haircut. In ‘The Boston Rag’ there’s a character named ‘Lonnie the kingpin’. Another Bard reference, this one widely shared: Lonnie was the sandwich man who would visit the dorms late at night, just as the munchies were making us ravenous, selling delicious ham and cheese sandwiches, potato chips and cola beverages that quenched our weed-parched throats.

‘Show Biz Kids’ is the band at their weirdest, and possibly most accessible. It’s a strange follow-up to two gold singles, considering it’s a hypnotic, enigmatic musical piece based around the world’s oldest Las Vegas joke. The girls sing ‘Go to lost wages, lost wages’, a 1950s American lounge comic’s reliable pun for Las Vegas. There’s a line about fans wearing Steely Dan T-shirts, which I took as an inside joke, because Steely Dan didn’t have T-shirts yet, as far as I knew. There may be yet another Bard reference, to a character named ‘El Supremo’, perhaps a bandito stoner in a dormitory mural, though I’d never seen it.

A more likely single might turn out to be ‘Pearl Of The Quarter’, with its lazy Louisiana steel guitar, soft as a ‘Cajun smile’ and cynical as ‘she loves the million-dollar words I say’. Fine drumming, as always, from Jim Hodder, who appears in this article for the first time.

The real Steely Dan heartbeat is ‘King of the World’. It moves from nostalgia for childhood, with imagery ranging from ham radio to Saturday afternoon westerns. Says Walter Becker: ‘Typical devastation. Like, what do you do at the end of the world? The sense of doom is overwhelming. We wrote it after watching Ray Milland in Panic in Year Zero!’

Cha-cha-cha!

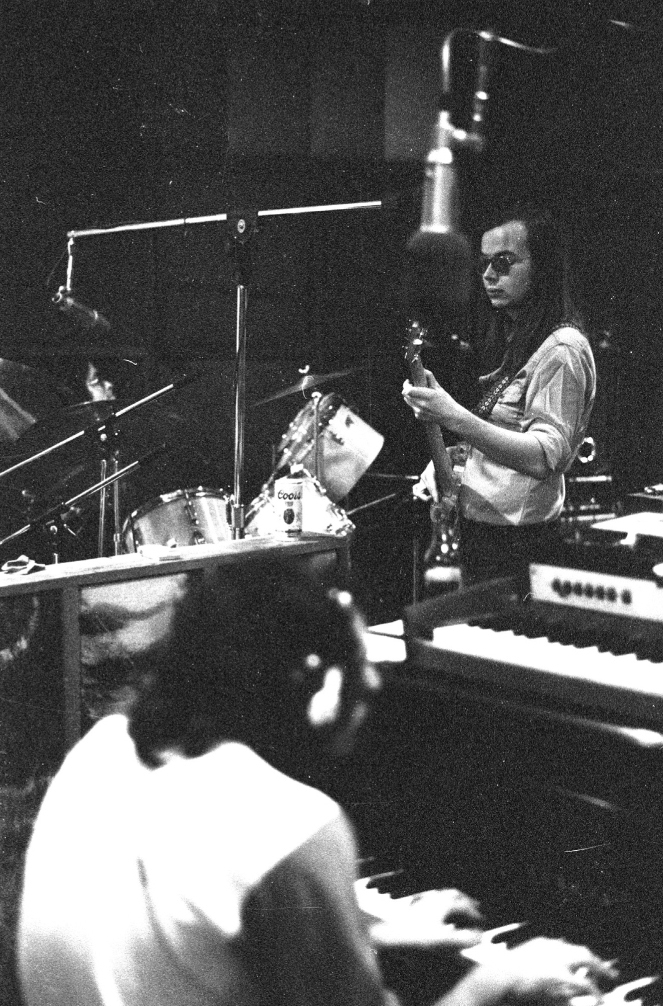

Donald Fagen at the piano and Walter Becker on bass during a session for Katy Lied.

Michael Ochs Archives/Stringer/Getty Images