1

Introduction

1

2

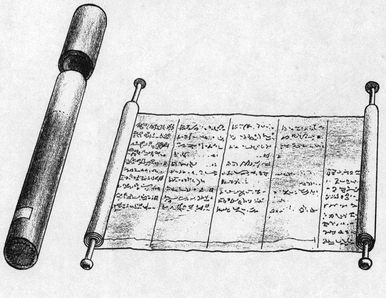

Paradoxically, the history of bookbinding begins many hundreds of years after the appearance of the first book, one of the earliest examples of which is an Egyptian papyrus roll composed of eighteen columns of hieratic writing, dating from the twenty-fifth century B.C. and stored in a tube “binding” (1). The roll form (from the Latin volumen, “roll of writing”) continued well into the Christian era, when parchment gradually replaced papyrus as a writing material. The arrangement of the writing in parallel columns separated by vertical lines held the potential for the development of an entirely new form. Eventually the idea of cutting the roll into a number of flat panels, each holding three or four columns, inspired a binding that was more convenient to use and that would prove to be more durable.

The first bound book was made up of single sheets hinged along one edge by means of lacing or sewing. In the Latin codex or manuscript book, the columnar arrangement was continued, with typical examples from Roman times having three or four columns to the page. Down to the present day, two- and three-column pages have been in common use, particularly in reference books and textbooks in which short lines contribute to easier reading. Partly for the sake of legibility, modern trade books are predominantly single column and consequently of a smaller trim size than books of earlier times.

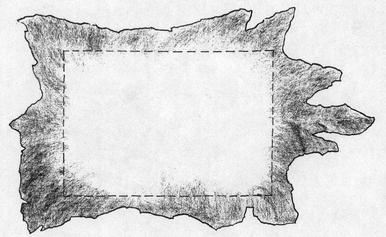

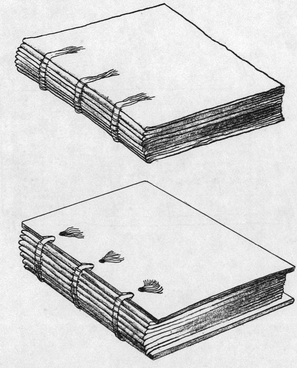

Early bindings exhibit all the basic construction elements that characterize modern bindings. They were made up of folded sheets collected into gatherings, or signatures, and sewn onto cords running across their backs. The pages of these books were large, probably much influenced by the size of the animal skins from which the parchment was made (2). Subsequently, wooden boards were placed on either side of the sewn signatures—but not attached to them—in positions corresponding to the front and back covers, to protect the book’s pages. At some later time it was discovered that the cords to which the signatures were sewn could as easily be laced directly into the edges of the boards to form a more compact and durable unit (3). The fundamental evolution of bookbinding was completed when the whole volume was covered with a sheet of leather to conceal the cords and sewing, to reinforce the hinges, and to provide protection and permanence (4).

The development of bookbinding is both simple and complex. In the past eighteen hundred years the basic construction of the book has not changed, as an examination of a contemporary binding will show. It is still a series of signatures sewn one to the other at the folds and secured between two boards whose outer surfaces are covered. Just as the perfection of any technique cannot proceed in isolation from other factors, bookbinding has been influenced by many events having nothing directly to do with books or even literature.

The early monastic orders were the guardians of nearly all knowledge in the Middle Ages, with respect to both writing and scholarship. Thus it is not surprising that the same persons to whom these skills were entrusted also assumed the role of bookbinders. Their craftsmanship reflected a thoroughness of education available to only a privileged minority. Hence the beginnings of bookbinding are associated with the church, with ecclesiastical history and literature, and with manuscript reference books.

3

4

The large size of early manuscript writing (5) was governed by the writing tool itself and demanded a generous page size, while the considerable thickness of the handmade paper was mostly what contributed to the bulk of the bound book. Letter by letter, each word, line, and page was patiently handwritten and usually enhanced with flourished initials illuminated in brilliant colors. The bindings were of leather, their large boards inviting decoration. There are countless examples with richly tooled designs combined with settings of gems, rare stones, and heavy gold leaf (6). As a further embellishment, engraved gold clasps or latches were attached to the boards to hold them closed. Working with good materials and virtually unlimited time, the monastery binders produced work of uncompromising quality and durability. These ceremonial reference books were quite literally—then as now—original works of art, intended for the use of only a select few people. Quite apart from their content and visual beauty, perhaps their greatest value lay in the impossibility of replacing them, for many of these limited editions would have been copied from equally unique volumes borrowed with difficulty from another library at a great distance. Needing to be carefully guarded, in the monastery library these rare books were hitched by chains to the shelves or reading tables.

5

6

Bookbinding was also affected by the art of papermaking, which was introduced to Europe from China in the tenth century. Sheets of this new handmade material approximated the weight of parchment, but they could be folded, pierced, and sewn with greater ease. As the knowledge of papermaking spread, it was found that the large sheets of this new material need not always be used as a single fold, or folio size (7). Paper was pliable enough to withstand being folded several times without damage. Two folds produced the 9 x 12-inch quarto page, and three made a 6 x 9-inch octavo comprising eight leaves, or sixteen pages—a size corresponding closely to the average trim size of a modern book. This readily available material, coupled with an awakened interest in more books on a broadening range of subjects, set the stage for a new phase in the development of bookbinding—the advent of the block book, in which both the text and the illustrations for each page were cut in relief on blocks of wood, one block for each page. Scores of identical impressions could be printed from the blocks, and the blocks could be safely stored and reprinted as required. Although infinitely faster than making duplicate copies one at a time with a reed pen, the task of cutting thousands of individual letters in wood was still enormously tedious.

A development amounting to a revolution came in the fifteenth century with the perfection by Johann Gutenberg of printing from movable type. By this process of composing words from individual type letters, an entire page could be set and hundreds of impressions printed in a relatively short time. Moreover, once the edition of a page had been printed, the type could be sorted, or distributed, and used again to set another page.

7

8

Yet this astonishing invention did not immediately bring about a reduction in the trim size of books, for the early movable type letters were almost exact copies of the handwritten characters of the manuscript and block books. Printing from movable type did, however, dramatically multiply the numbers of books in circulation as well as increase the demand for bookbinders, and it transformed bookbinding from a strictly cottage trade to one of mass production. In the course of time bookbinding moved away from the monasteries into the printers’ shops, and ultimately to quite separate binding establishments.

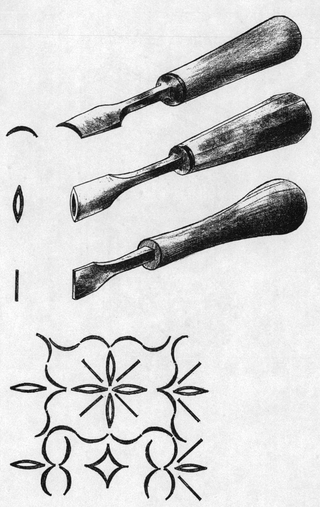

Leather persisted as the covering material, while the recently imported art of blind and gold tooling long practiced in the East gave bookbinding a fresh impetus. The cords on which the signatures were sewn, and which were covered with leather, made pleasing raised bands and set off panels on the backbone of the book. This was to become an important design feature, as the panels were filled with hand-tooled decoration built up with impressions from various small tools (8).

European royal families and others of the aristocracy inadvertently sponsored the further development of distinctive binding styles through their patronage of many skilled binders. Coats of arms, crests, and heraldic devices were made the central motifs of bindings that they commissioned for their private libraries. Curiously, these binding styles are known not by the names of the binders but by those who ordered the work. The Grolier bindings, for example, were named for Jean Grolier, Vicomte d’Aguisy, treasurer of France in 1545.

The Industrial Revolution also left its mark on the bookbinding trade. In the early 1900s, concurrent with the machine invasion of every conceivable manufacturing field, binding methods suffered severe and often degrading innovations. Where formerly the tooling of leather had been strictly a hand operation, whole panels of tooling were now machine stamped in a single, swift motion. While this might have been meant to put fine binding within the reach of everyone of modest means, the new stampings lacked the taste and artistry of handwork. Rather than evolving a new decorative style stemming from the machine’s possibilities or limitations, this new technique aimed at low cost gave only the superficial impression of handwork while failing to achieve its quality. This revision of standards for the sake of economics was also reflected in the use of cheaper paper, machine-woven cloth, and shortcut binding methods. When cloth tape replaced cords in the sewing operation, an attempt was made to retain the elegant look of hand binding by attaching false bands to the backbone, in imitation of the true, full leather binding (9).

The hollow back signaled another new departure—the invention of the case binding, in which the cover boards and backbone were glued flat to a sheet of cloth or paper quite independent of the sewn signatures. All titling and decoration was stamped on the flat case, the finished case and signatures then being united and glued to one another by means of a strip of cloth mull and the endsheets (10).

9

10

By the late 1800s the book had become a permanent democratic property. Machine methods were firmly entrenched and were producing books in almost unlimited quantities at popular prices. It was now that a group of designers and printers, under the leadership of William Morris in England, and an impressive list of craftsmen, typified by T. J. Cobden-Sanderson, were engaged in a revival of sound practices through work done in the many private presses. Concerned with traditional quality bookmaking, these presses used well-designed typefaces, hand typesetting, handmade paper, hand presses, and good binding methods to produce fine books.

This movement seemed to point out that whereas all bookbinding had once been of remarkably high quality, fine binding had now become a specialized craft, isolated from the book manufacturing industry as a whole and with a very small market consisting of collectors, special libraries, and a limited number of people who appreciated not only a book’s content but also the workmanship of its printing and binding.

This book is intended as a manual of instruction in the traditional methods of hand binding and as a reference for students and professionals in publishing and its allied trades.

For further study of bookbinding in general and traditional leather binding in particular, there are numerous excellent books to consult, among them Douglas Cockerell, Bookbinding and the Care of Books, London, 1953; Bernard C. Middleton, The Restoration of Leather Bindings, Chicago, 1972; and Jeff Clements, Bookbinding, London, 1963.

Aldren A. Watson

North Hartland, Vermont