Military Personnel:

Col. James A. Conn, governor general, d. 3 CR

Capt. Ada P. Beaumont, lt. governor, d. year of founding

Maj. Peter T. Gallin, personnel

M/Sgt. Ilya V. Burdette, Corps of Engineers

Cpl. Antonia M. Cole

Spec. Martin H. Andresson

Spec. Emilie Kontrin

Spec. Danton X. Norris

M/Sgt. Danielle L. Emberton, tactical op.

Spec. Lewiston W. Rogers

Spec. Hamil N. Masu

Spec. Grigori R. Tamilin

M/Sgt. Pavlos D. M. Bilas, maintenance

Spec. Dorothy T. Kyle

Spec. Egan I. Innis

Spec. Lucas M. White

Spec, Eron 678-4578 Miles

Spec. Upton R. Patrick

Spec. Gene T. Troyes

Spec. Tyler W. Hammett

Spec. Kelley N. Matsuo

Spec. Belle M. Rider

Spec. Vela K. James

Spec. Matthew R. Mayes

Spec. Adrian C. Potts

Spec. Vasily C. Orlov

Spec. Rinata W. Quarry

Spec. Kito A. M. Kabir

Spec. Sita Chandrus

M/Sgt. Dinah L. Sigury, communications

Spec. Yung Kim

Spec. Lee P. de Witt

M/Sgt. Thomas W. Oliver, quartermaster

Cpl. Nina N. Ferry

Pfc. Hayes Brandon

Lt. Romy T. Jones, special forces

Sgt. Jan Vandermeer

Spec. Kathryn S. Flanahan

Spec. Charles M. Ogden

M/Sgt. Zell T. Parham, security

Cpl. Quintan R. Witten

Capt. Jessica N. Sedgewick, confessor-advocate

Capt. Bethan M. Dean, surgeon

Capt. Robert T. Hamil, surgeon

Lt. Regan T. Chiles, computer services

Civilian Personnel:

Secretarial personnel: 12

Medical/surgical: 1

Medical/paramedic: 7

Mechanical maintenance: 20

Distribution and warehousing: 20

Robert H. Davies d. CR 3

Security: 12

Computer service: 4

Computer maintenance: 2

Librarian: 1

Agricultural specialists: 10

Harold B. Hill

Geologists: 5

Meteorologist: 1

Biologists: 6

Marco X. Gutierrez

Eva K. Jenks

Jane E. Flanahan-Gutierrez b. 2 CR

Education: 5

Cartographer: 1

Management supervisors: 4

Biocycle engineers: 4

Construction personnel: 50

Food preparation specialists: 6

Industrial specialists: 15

Mining engineers: 2

Energy systems supervisors: 8

ADDITIONAL NONCITIZEN PERSONNEL:

“A” class: 2890

Jin 458-9998

Pia 86-687

Jin Younger b. year of founding

Mark b. 3 CR

Zed b. 4 CR

Tam b. 5 CR

Pia Younger b. 6 CR

Green b. 9 CR

“B” class: 12389

“M” class: 4566

Ben b. 2 CR

Alf b. 3 CR

Nine b. 4 CR

“P” class: 20788

“V” class: 1278

i

Year 22, day 192 CR

It was a long walk, a lonely walk, among the strange hills the calibans raised—but her brothers were there, and Pia Younger kept going, out of breath by now, her adolescent limbs aching with the running. She always ran on this stretch of the trail, where the mounds and ridges were oldest and overgrown with brush. She never admitted it to her brothers, but it disturbed her to cross this territory. Here. With them.

Ahead were the limestone heights where the old quarry was; the elders had built the town with limestone, but they took no more stone there nowadays except what they could bribe her brothers to bring down. Afraid, that was it; elders were afraid to cross the territory of the calibans. Youngers had this place, the deep pit where they had done blasting in the old days, and they owned the pile of loose stone that they loaded up and brought back when they wanted to trade. A lot of the youngers in the azi town came here, her brothers more than most, but the elders never would; and the main-Camp elders, they huddled in their domes and defended themselves with electric lights and electric wires.

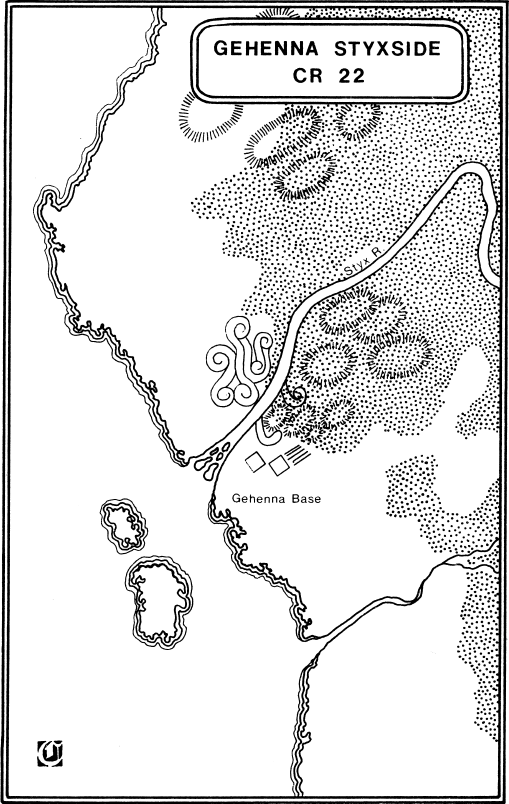

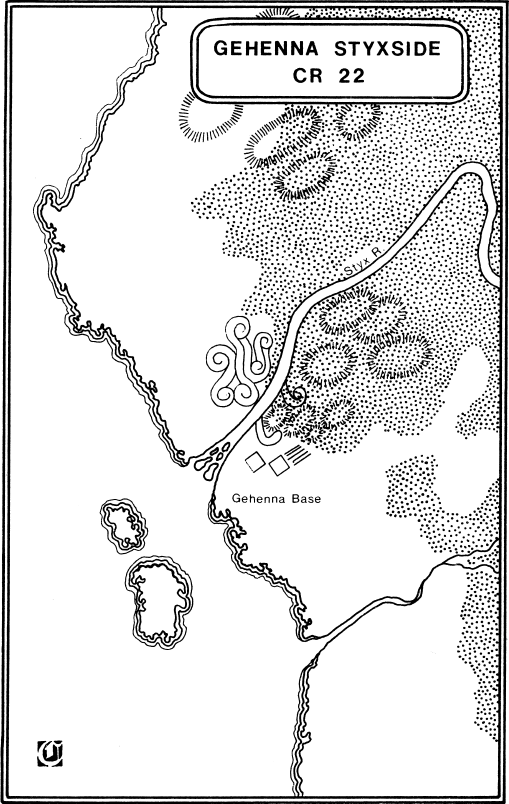

She caught a stitch in her side and slowed to a limp when she reached the old trail, which had been a road once upon a time, a rain-washed road paved with limestone chips and overgrown with small brush and weeds and fallen away so that in some places it was wide enough for one walker only. She looked back when she made the turn—it was that kind of view that the eye had to go to, that sprawling perspective out over all the world, the lazy S of the Styx and the mounds of the calibans like wrinkled cloth strewn on both sides of it, some under the carpet of trees and some new and naked; and caliban domes that mimicked the domes of the main Camp.

Calibans had never made domes, her father said, until they saw the domes of main Camp; but they made them now, and larger and grander, raising great bald hills on this side and that of the Styx. Beyond them were the solid hills, the natural hills; and then the fields all checkered green and brown; and the rusting knot of giant machines—and the tower, and the big shining tower that caught the sun and fed power to the little cluster of domes before the graveyard and the sea. All of that, in one blunt sweep of the eye, the whole world: and this height owned it all. That was why her brothers came here, to look down on all of it; but she was sixteen—not yet, her brothers said to her. Not yet for you.

What her parents said to her coming here—but they did everything the Council said; and saying no was part of it.

She began to run again, uphill, pushing past the brush, careless now because there was nothing but snakes to worry about up here in the day; and calibans ate snakes, and noise frightened both, so she made all the noise she could.

A whistle caught her ear, above her on the rim; she looked up, at a head that appeared over the rim of the cliffs, head and shoulders, black hair blowing on the wind. Her brother Zed. “I’ve got to come up,” she called.

“Come on up, then,” he called back. One had to be Permitted to come up to the heights; and she dusted her hands on her coveralls and came up the last few turns . . . stopped on that bald crest of stone slabs and scant brush and sat down panting for breath on the lefthand slab of the two that served them for a gate, there by a bitterberry. All her elder brothers were up here. And Jane Flanahan-Gutierrez. Her eyes caught that with shock and jealousy. Jane Flanahan-Gutierrez from the main Camp, of the dark skin and the curling black hair . . . there with all the boys; and she knew at once what they had been doing up here—it was in her brothers’ eyes, like summer evening heat. They looked older, suddenly, like strangers. Jane looked that way too, disheveled clothes, her coveralls unzipped to here, staring at her as if she had been dirt. Her four older brothers, Jin and Mark and Zed and Tam; and the boys from down the row in town, Ben and Alf and Nine. They fronted her like a wall, her brothers the dark part of it and the Ben/Alf/Nine set all red and blond. And Jane Flanahan-Gutierrez.

“You let her up here,” Ben said to Zed. “Why let her up here?”

“I know what you’re doing,” Pia said. Her face felt red. She was still gasping for breath after the climb; she caught a mouthful of air. Jane Flanahan-Gutierrez sat down on another rock, her hands on either side of her, flaunting sex and satiation. “You think,” Pia gasped, “you think it’s anything? Jin, our father sent me. To find you all. Green’s run off again. They want you back to help.”

Her brothers settled, one by one, all but her brother Jin, who was eldest, who stood there with his face clouded and his hands caught in his belt. Green: that was the sixth of them. Youngest brother.

“That boy’s gone,” Ben said, with the disgust everyone used about Green; but: “Quiet,” Jin Younger said, in that tone that meant business, that could frighten elders into listening to whatever Jin wanted to say. “How long?”

“Maybe since morning,” Pia said hoarsely. “They thought he was off with some boys. He ran off from them. They didn’t send anyone back to tell. Pia’s looking in the Camp; but Jin’s out in the hills. Hunting this way. He asked us, Jin; our father asked us. He’s really scared.”

“It’s going to get dark.”

“Our father’s out there, all the same. And he doesn’t know anything. He could fall in a burrow, he could. But I don’t think he’ll quit.”

“For Green.”

“Jin—” She talked only to Jin, because he made up the minds of the rest. “He asked.”

“We’d better go,” Jin said then; so that was it: the others ducked their heads and nodded.

“What do we do with that brother of yours,” Ben asked, assuming they were going too, “if we find him?”

“Hey,” Jane said, “hey, I have to get back to the Camp. You said you’d walk me back to the Camp.”

“I’ll walk you back,” Pia said with a narrow look. “That trail down’s really bad. A careless body might slip.”

“You’d better watch who you talk to,” Jane said.

“Azi. That what you reckon, maincamper? Think I’m scared? You watch yourself.”

“Shut up,” Jin said.

“One of you,” said Jane, “has to get me back. I can’t wait around while you track that brother of yours down—I know; I know all about him.”

“We’ll be back. Just wait.”

“He’s gone, don’t you think that? When they go, they go.”

Pia gathered herself up again without a word, started off down the road without a backward look, not inside; and before she had gotten to the first downslope there was a skittering of pebbles and a following in her wake: the whole troop of her brothers was gathered about her, and the down-the-row boys too.

“Wait!” Jane shouted after the lot of them. “Don’t you go off and leave me up here.” And that was satisfaction. They would get her down—later. When they had seen to Green again. A stream of words followed them, words they swore by in the main Camp in the longest string Pia had ever heard. Pia marched down the winding track without looking back, hands in her pockets.

“That Green,” Ben muttered. “Going to do what he likes, that’s what. Going to get to what he wants sooner or later.”

“Quiet,” Jin Younger said, and Ben kept it to himself after that, all the long way down.

It was better going back. In company. Pia began to pant with exhaustion—her tall brothers had long legs and they were fresh on the track, but she kept going, with the stitch back in her side, not wanting to admit her tiredness. Green—as for Green, Ben might be right. She had five brothers and the last was wild; was thirteen, and wandered in the hills.

And those who did that—they went on wandering; or whatever they did, who gave up humankind.

It was the third time . . . that Green had gone.

“This time,” Pia said out of her thoughts, between gasps for air, “this time I think we have to get him, us. Because I don’t think our father can find him fast enough.”

“This time—” Jin Younger said, walking beside her, themselves out of hearing of the others if he kept his voice low, “this time I think it’s like Ben said.”

He admitted that to her. Not to the others. And it was probably true.

But they kept going all the same, down into the woods the calibans had grown, among the mounds and the brush in the late afternoon. “Where’s Jin hunting?” Jin Younger asked.

Pia pointed, the direction of the Camp. “From Camp looking toward the river. That’s what he thought—the river.”

“Probably right,” Jin Younger said. “Probably right for sure.” He squatted down, cleared ground with the edge of his hand, took a stick and scratched signs as the others gathered. “I think Mark and I had better find our father: that’s furthest. And Zed and Tam, you go the middle way; Ben, you and Alf go with them and split off where you have to go up to cover the ground; and Nine, you and Pia go direct by the river way. Pia’s got most chance of talking to Green: I want her there where he’s most likely to go. We draw a circle around him and sweep up our father too, before some caliban gets him.”

That was Jin Younger: that was her brother, whose mind worked like that, cool and quick. Pia got up from looking at the pattern and grabbed Nine’s hand—Nine was eighteen, like Zed; and red and gold and freckled all over. They all moved light and quick, and in spite of the prospect in front of them, Pia went with a kind of relief that she was doing something, that she was not her mother, searching the town because she had to do something, even a hopeless thing, lame as Pia elder was, worn out from Green, aching tired from Green—

Lose him this time, Pia thought, in her heart of hearts. Let him go this time to be done with it; and no more of that look her parents had, no more of doing everything for Green.

But if they lost him, they had to have tried. It was like that, because he was born under their roof, stranger that he was.

They took the winding course through the brush-grown mounds, she and Nine, hand in hand, hurried past the gaping darknesses under stones that were caliban doorways—sometimes saucer-big eyes watched them, or tongues flicked, from caliban mouths mostly hid in shadow and in brush.

And the way began to be bare and slithery with mud, and tracked with clawed pads of caliban feet, which was a climbway calibans used from the Styx or a brook that fed it. Ariels scurried from their track, whipping their tails in busy haste; and flitters dived in manic profusion from the trees—some into ariel mouths. Pia brushed the flitters off, a frantic slapping at the back of her neck, protecting her collar, and they jogged along singlefile now, slid the last bit down to the flat, well-trampled riverside, where calibans had flattened tracks in the reeds of the bogs, and clouds of insects swarmed and darted.

Desolation. No human track disturbed the mud flats.

“We just wait,” Pia said. “He can’t have gotten past us unless he went all the way around the heights on the east.” She squatted down by the edge of the water and dipped up a double handful, poured it over her head and neck, and Nine did the same.

“Why don’t we take a rest?” Nine suggested, and pointed off toward the reeds.

“I think we ought to walk on down the way toward the rocks.”

“Waste of time.”

“Then you go back.”

“I think we could do something better.”

She looked suddenly and narrowly at him. He had that look they had had up there, with Jane. “I think you better forget that.”

He made a grab at her; she slapped his hand and he jerked it back.

“Go after that Jane,” she said, “why don’t you?”

“What wrong with you? Afraid?”

“You go find Jane.”

“I like you.”

“You’ve got no sense.” He scared her; her heart was pounding. “Jane and all of you, that’s all nice, isn’t it? But I say no, and you’d better believe no.”

He was bigger than she, by about a third. But there were other things to think of, and one was living next to each other in town; and one was that she always got even. People knew that of Pia Younger; it was important to have people believe that, and she saw to it.

And finally he made a great show of sulking and dusting his hands off. “I’m going back,” he said. “I don’t stay out here for nothing.”

“Sure, you go back,” she said.

“You’re cold,” he said. “I’ll tell how you are.”

“You tell whatever you like; and when you do, I’ll tell plenty too. You make me sound bad, you make my brothers sound the same. We figure like that. You’re three and we’re six. You make up your mind.”

“You’re five now,” he said, and stalked off.

Afterward she found her hands sweating, not sure whether it was because of the sun or her temper or the thought that she could have had Nine, who was not bad for a first; but he was ugly inside, if not out. And lacking that reason, she thought of her mother, and how she had been young before Green started growing up. She thought about babies and the grief her mother had had of them, and that dried the sweat all at once.

So they might be five now. Green might be gone. And that might cure them of all their troubles at once, if only they could prove they had searched; if they could get Green out of Jin and Pia’s minds.

They went out to get their mother and father back for their own: that was why they went. That was why she had known that her brother Jin would come.

And if Nine had run back to his brothers, Pia still meant to stay where her brother said, to watch the bank. The rocks offered the most likely vantage, where the cliffs tumbled down to the Styx, where calibans sunned themselves and where anyone headed upriver had to go.

She had no fear of her brother Green. It was the others of his sort she had no desire to meet; and she wanted somewhere to watch unseen.

ii

The sun was halfway down the sky, and Jin elder moved with a sense of desperation, his breath short and shallow, his senses alive with dread on all sides. The wooded mounds surrounded him, offered dark accesses out of which calibans could come. Young ones challenged him, man-sized, athwart his path, and he scrambled aside on the hill and kept going.

He might call aloud, but Green would never answer to his name, hardly spoke at all, and so he did not waste the breath. It was a question of overtaking his son, of finding him in this maze when he had no wish to be found. It was impossible, and he knew that. But Green was his, and whatever Green was, however strange, he tried, as his wife tried, in the town, already knowing her son was gone—searching among the thousands of houses, asking faces that would go blank to the question—“Have you seen our son? Have your children heard from him? Is there anyone who knows?”—They would shut the doors on her as they would on the night or on a storm, not to have the trouble inside with them, whose houses were secure. Pia had no hope; and he had none, except in his rebel children, his other sons and his daughter, who might possibly know where to look, who ran wild out here—but not as wild as Green.

He slowed finally, out of breath, walked dizzily among the mounds. Now the sun was behind them, making pockets of dark. A body moved, slithered amid the thick brush, among the trees which had grown here, this side of the river. The sight was surreal. He recalled bare meadow, and gentle grass, and the first beginnings of a mound; and caliban skulls piled behind main dome. But all that was changed; and a forest grew, all scrub and saplings. Fairy flitters came down on his shoulder, clung to his clothing, making him think of bats; he beat them off and recalled that they were lives—which touched a faint, far chord in him, of guilt and of dread. The world was full of life, more life than they could hold back with guns or fences; it came into the town at night; it seduced the children and year by year crept closer.

A heavy body thrust itself from a hole—a caliban flicked its tongue at him; an ariel scurried over its immobile back and fled into the dark inside. He started aside, ran, slowed again with a pain in his side . . . sat down at last, against the side of a mound, by one of the rounded hills, the domes the calibans made.

And leapt up again, spying a white movement among the saplings on the ridge. “Green,” he called.

It was not Green. A strange boy was staring down at him, squatting naked atop the ridge—thin, starved limbs and tangled hair, improbable sight in the woods. It was the image of his fears.

“Come down,” he asked the boy. “Come down—” Ever so softly. Never startle them; never force—It was all his hope, that boy.

And the boy sprang up and ran, down the angle of the hill among the brush; Jin ran too—and saw the boy dive into the dark of a caliban access, vanishing like nightmare, confirming all that he had dreaded to know, how they lived, what they were, the town’s lost children.

“Green,” he called, thinking that there might be others, that his son might hear, or someone hear, and tell Green that he was called. But no answer came; and what the mound had taken in, it kept. He moved closer, climbed the slope with all his nerves taut-strung. He went as far as the hole and put his head inside. There was the smell of earth and damp; and far away, down some narrow tunnel, he heard something move. “Green,” he shouted. The earth swallowed up his voice.

He crouched there a moment, arms flung across his knees, despair thicker about him than before. His children had all gone amiss, every one; and Green, the different one, was stranger than all the strange children he had sired. Green’s eyes were distant and his mind was unknowable, as if all the unpleasantness of the world had seeped into Pia while she carried him, and infected his soul. Green was misnamed. He was that other face of spring, the mistbound nights when calibans prowled and broke the fences; he was secret things and dark. He had lost himself, over and over again; had shocked himself on the fences, sunk himself in bogs—had lost himself into the hills, and played with ariels and stones, forgetting other children.

Jin wept. That was his answer now that he was like born-men and on his own. He mourned without confidence that there would be comfort—no tapes, now; nothing to relieve the pain. He had to face Pia, alone; and that he was not ready to do. He pictured himself coming home with daylight left, giving up, when Pia would not. When he failed her, she would come out into the hills herself: she was like that, even frail as she grew in these years. Pia, to lose a son, after all the pain—

He got up, abandoning hope of this place, kept walking, brushing the weeds aside in the trough between the mounds, going deeper and deeper into the heart of the place. All the way to the river—that was how far he must go, however afraid he was, all along this most direct track from the village to the river, as close as he could hew to it.

Brush stirred above him on a ridge: he looked up, expecting calibans, hoping for his son—

And found two, Jin and Mark, standing on the wooded ridge above him, mirrors of each other, leaning on either side of a smallish tree.

“Father,” Jin Younger said—all smug, as if he were amused. And hostile: there was that edge always in his voice. Jin 458 faced his son in confused pain, never knowing why his children took this pose with him. “A little far afield for you, isn’t it, father?”

“Green is lost. Did your sister find you?”

“She found us. We’re all out looking.”

Jin elder let the breath go out of him, felt his knees weak, the burden of the loss at least spread wider than before. “What chance that we can find him out here?”

“What chance that he wants to be found?” Mark asked, second-born, his brother’s shadow. “That’s the real matter, isn’t it?”

“Pia—” He gestured vaguely back toward the camp. “I told her I could go faster, look further—that you’d help; but she’ll try to come—and she can’t. She can’t do that anymore.”

“Tell me,” Jin Younger said, “would you have come for any of us? Or is it just Green?”

“When you were four and five—I did, for you.”

Jin Younger straightened back as if he had not expected that. He scowled. “Sister’s gone on down by the river,” he said. “If we don’t take Green between us, there’s no catching him.”

“Where’s Zed and Tam?”

“Oh, off hereabouts. We’ll find them on the way.”

“But Pia’s on the river alone?”

“No. She’s got help. Anyhow, Green won’t hurt her. Whatever else, not her.” Jin Younger slid down the slope, Mark behind him, and they caught their balance and stopped at the bottom in front of him. “Or didn’t that occur to you when you sent her into the hills by herself?”

“She said she knew where you were.”

His sons looked at him in that way his sons had, of making him feel slow and small. They were born-men, after all, and quick about things, and full of tempers. “Come on,” Jin Younger said; and they went, himself and these sons of his. They shamed him, infected him with tempers that left him nothing—his sons who ran off to the wild, who took no share of the work in the fields, but cut stone when the mood took them, and dealt with born-men for it in trade, their own discovery. Well enough—it was not calibans that drew them; but laziness. He tried to guide them, but they had never heard a tape, his sons, his daughter . . . who ran after her elder brothers.

Who left her youngest brother to himself; while Green—started down a path all his own.

Jin thought that he might have done better by all of them. In the end he felt guilt—that he could not tell them what he knew, and how: that once there had been ships, that ships still might come, and there was a purpose for the world and patterns they were supposed to follow.

It was the first time, this walk with his eldest sons, that they had ever walked in step at all—young men and a man twice their age, the first time he had ever come with them on their terms. He felt himself the child.

iii

The way was strange along the bank, the reeds long since left behind, where the river undercut the limestone banks and made grottoes and caves. The calibans had taken great slabs of stone and heaved them up in walls—no caprice of the river had done such things. It was a shadowed place and a hazardous place, and Pia refused to go into it. She perched herself on a rock above the water, arms about her knees, in the shadows of the trees that arched out from rootholds in the crevices of the stone. Moss grew here, in the pools; fish swam, black shapes in the ripples, and a serpent moved, a ripple through the shallow backwaters of the river. Ariels and flitters left tracks on the delicate sand, washed up on the downstream side of the stones, and at several points were the grooves calibans made in their coming up from the river, deep muddy slides.

She looked up and up, where the cliffs shadowed them, scrub trees clinging even to that purchase. There were caves up there. Possibly ariels found them accessible, but no human could climb that face. Bats might nest there. There might possibly be bats, though they came infrequently to the river.

And very much she wished for her brothers . . . the more when something splashed and moved.

She turned; caught her breath at the sight of the coveralled figure which had come up behind her among the rocks.

“Green,” she said softly, ever so quietly. Her youngest brother looked back at her, out of breath, with that strange, sober stare he used habitually. “Green, our father’s looking for you.”

A dip of the head, one of Green’s staring nods, his eyes hardly leaving her. He knew, Green meant; she knew how to read him.

“You know,” she said, “how upset they’ll be.”

A second nod. There was no hint of distress on Green’s face. No feeling at all. She remembered why she hated this brother, this feelingless nothing of a brother who had changed everything when he came.

“You don’t care.”

Green blinked, solemn as one of his leathery pets.

“Where do you think you’re going?” she asked. “Doing what? You want to starve?”

A shake of the head.

“Speak to me. Once, speak to me.”

Green sank down on his haunches on the bank and gathered up a stone, laid it flat on another one. He no longer listened.

“That’s nice,” she said. For one desperate moment she thought of warning him off, telling him the others were coming, so that he would run off, would escape, so that they would never again have to worry about him. But the words stuck in her throat, an ultimate dishonesty—not for themselves, but because it would be hard to look at her father and claim Green had run away.

She sidled closer while her brother made patterns with the stones . . . sidled closer, snatched suddenly at his arm and spoiled his pattern. He came up flailing and splashing into the margin of the water, twisted in her grip, and of a sudden her foot skidded on wet moss, spilling them both.

He twisted loose. “Green,” she yelled after him, as he went skittering this way and that among the higher rocks.

But he was gone, and she was sitting in the water, soaked and shaken to think that finally he had gotten away. She was jolted by the fall—embarrassed and no small bit angry that he had outdone her, her little brother.

But gone. They were free of him. Finally free.

She gathered herself up then and laved off her hands and muddy coveralls, settled herself finally to dry off and wait.

And when her brothers brought her father with them down the banks of the river, she rose up off her rock to meet them in the twilight.

“He pushed me,” she said as dourly as she could. “He hit me and he got away.”

She was not sure what to expect—focused only on her father’s eyes.

“Did he hurt you?” Jin elder asked, and his question warmed her heart with a warmth she had hardly felt since she was small. There was concern there; care for her. He took her into his arms and hugged her as he had done when she was small, and in that moment she looked beyond him, at her brothers; and at Nine and his kin, with a warning and a triumph in her smile.

She was someone again, with Green gone. She looked at Jin Younger, and Mark and Zed and Tam, and they knew what she had done. They had to know, that she had not struggled half hard enough; and why. So she was one of them: co-conspirator. Murderer, perhaps.

“You tried,” Jin elder said. But she had no twinge of conscience, looking up into his face, because, at least in intent, she had done that much.

“Go back with father,” Jin Younger said. “We’ll search further.”

“No,” Jin elder said. “Don’t. I don’t want that.”

Because he was afraid of this place, Pia thought; he took care for them now and not for Green. He had given up, and that was sweet to hear; that was what they had wanted to hear.

“I’ll look,” Jin Younger insisted, and turned away, up the bank, up among the rocks, never asking which way Green might have gone. It was the wrong way; and Mark went off that way too, toward the cliffs where Jin was leading. So she understood.

“We’d better get home,” Zed said. “It’s getting dark. He’s off into the wild places. And there’s no help in all of us wandering around out here.”

“Yes,” Jin elder said finally, in that quiet way he had, that resigned things he could no longer mend. For once Pia felt a shame not for him, for the simple answers her father gave, but on their account; on her own. Yes. Like that. After walking through territory that was a terror to him. Yes. Let’s go home. Let’s tell mother how it is.

Her brothers were in no wise bound after Green. They had no interest in Green. They had left themselves a main-camper up on the cliffs and night was falling; it was time to go get Jane Flanahan-Gutierrez down before she went silly with panic. Games were done. The night was coming. Fast.

And as for her brother, as for Green, spending the night out in the cool damp, slithering underearth where he chose to be—

She shivered in the circle of Jin elder’s arm, turning back to the way along the shore. Nine and his brothers had already begun to walk back, having nothing to do with her father, and less with their own; besides, Nine had reason to avoid her now. So Jin elder was their possession, theirs, finally, the way he had been before Green existed.

iv

The sun sank, casting twilight among the stones, and Jane Flanahan-Gutierrez walked briskly down the trail among the mounds. Her knees shook just slightly as she went, making the downhill course uncertain. Fear was a knot in her stomach; and she cursed the azi-born, the beautiful, the so-beautiful and so hollow. Stay away from them, her mother said—stay away. And her father—said nothing, which was his habit. Or he delivered lectures on ships and birth-labs and plans gone amiss, and why she ought to think about her future, which she had no desire at all to hear.

Beautiful and hollow. No hearts in them. Nothing like them in the main Camp, no men so beautiful as Jin and his brothers, who were made to fill up the world with their kind. She wanted them; lowered herself to go off in the hills with them, like their own wild breed; and then their half-minded brother took to the hills as crazy as everyone expected of him, and they left her—just walked off and left her, up in the wild and the oncoming dark, as if she were nothing, as if it was nothing that Jane Flanahan-Gutierrez came out of the camp and wanted them.

Anger stiffened her knees; anger kept her going down the road into the brushy wild below the cliffs. She walked among the mounds, guided herself by the little sun that filtered through the trees atop the mounds.

And suddenly—a moving in the brush—there was a boy. Her heart lurched, clenched tight, settled out of its panic. She stopped, facing the boy in the halflight, among the brush. His coveralls were ragged, his hair too long. But he was human at least. Weirds, they called them, like Green, who lived wild among the mounds. But he was only a boy, not even in his teens—and a better guide, she suddenly hoped, than Jin and the lot of his friends had proved.

“I belong in the camp,” she said, taking the kind of stance she used when she expected something of the azi who served. “I want to go through the maze. You understand? You take me through.”

The figure beckoned, never speaking a word. It began to move off through the brush as vague as ever it had been.

“Wait a minute,” she said; and panic was in her mind—wondering how she was going to explain all this when she got home. She was going to be late. The fugitive showed no interest in helping her and they would be turning out search parties when it got dark. It was already beyond easy explaining—I was lost, mother, father; I was fishing; I got back in the mounds—“Wait!”

Brush moved behind her. She looked about, saw a half dozen others, who held out hands toward her, silent. “Oh, no,” she told them. “No, you don’t . . .” Her heart was crashing against her ribs. “I’m going on my own, thank you. I’ve just changed my mind.” She saw the eyes of some, the curious intensity, like the eyes of ariels. Crazy, every one. She edged back. “I have to get home. My friends are looking for me right now.”

They came closer, a soft stirring among their ranks, some of them in coveralls and some in only the remnant of clothing, or in blankets and sheeting. And strange, and silent and without sanity.

She remembered the other one, the one behind her—turned suddenly and gave a muffled outcry, face to face with the boy, close enough to touch—“You keep your hands to yourself,” she said, trying to keep the fear from her voice, because that was her chiefest hope—that there were still the town ways instilled in them, still the habit of obeying voices that had no doubt when they gave commands. “Be definite,” her mother had taught her, special op and used to moving people, “and know what you’re going to do if they refuse,”; but her father—“Know what you’re poking your finger at,” he said, whenever she was stung. She stared at the boy, a wild frozen moment before she realized the others were closing from behind.

She whirled, one desperate effort to shock them all and find an opening; but they snatched at her, at her clothing—wrong timing, she thought in utter selfdisgust, and only half thought that she might die. She hit one of them and laid him out the way her mother had taught her, but that was only one of them: the others caught her hair and held her arms. And some of them had clubs, showing her what might happen if she yelled.

Go along with it, she thought; none of the Weirds had ever killed. They were strange, but they had never yet kept their minds at anything: they would lose interest and then she might get away.

They tugged her arms, drew her with them . . . and this she let happen, noticing everything, every landmark. Jin and his brothers would find her; or she might get away; or if she could not, then her father would come looking, with her mother and the specials who knew the hills and the mounds. The camp would come with guns; and then they would be sorry. The important thing now was not to startle them into violence.

The way they walked twisted and turned in the maze, among wooded ridges and through thickets, until she had only the sunset to rely on for direction. Now she began to feel lost and desperate, but something—be it common sense or despair itself—still kept her from sudden moves with them.

They came to a hill, one of the caliban domes. A boy crouched there, dark of hair, who beckoned her inside, into the dark, gaping entry.

“Oh, no, I won’t. They’ll miss me, you understand. They’ll come—” Hunting, she had almost said, and swallowed the very thought of shooting calibans. They were the Lost, these boys, this strange band. A shiver ran over her skin.

“Come.” The boy stretched out a hand, fingers spread upward, closed his fist with a slow intimation of power, so real it seemed to narrow all the space in the region, to draw in all that was. A second time he beckoned. Hands closed about her arms, propelled her forward . . . in a kind of paralysis—they brought her to him, this beautiful young man.

“Green,” she murmured, knowing him. It was her brother’s look on him, but changed. Mad. Crazed.

And others came, older than he, male and female.

“They’re looking for you,” she said. “You’d better go.”

But then one of the young men came down from atop the hillside, came close to her, that same far distance in his expression. She might have been a stone. She was not really afraid of him for that reason—until he put his hand on her breast.

“They won’t like that,” she said, “the people in the camp.” And then she wished she had not said that at all; her wish was to get out of here alive, and threatening them was not the way to assure that. The youth fingered her clothing, and began at the closing of it. She stood quite, quite still, not minded to lose her life to these creatures.

He was beautiful beneath the dirt. Most were, who came of azi lines. They were gentle in their moves—all of them curiously gentle, stroking her hair, touching her now without violence, so that it began to wander somewhere between nightmare and dream.

v

“She’s not here,” Jin Younger said, looking about the rocks and scrub of the summit—looked at his brother as if Mark could comprehend any more than he what kind of craziness had taken Jane Gutierrez off the heights. “She’s just not here.”

“She’s got to have tried it on her own,” Mark said, no less than what Jin had in his own mind. Jin pushed past his brother at the narrow passage up among the rocks and started down the trail at a run.

“We’ve got to get the rest of us,” Mark called after him. “We’ve got to get some help fast.”

“You go,” Jin called back, and kept going. His brother yelled other things after him, and he ignored them.

The sun was throwing the last orange light into the clouds, glinting like fire off the solar array down in the camp, like miniature suns; and around that brightness was the dark. She had come to them, this main Camp woman, her own choice, come to him in particular, because he had that about him, that he could impress any woman he liked—he and his brothers. She came into the wild country, against all the rules and regulations: that was her choice too; and he was not one to turn away such favors. It had been good, up on the ridge. Good all day, because Flanahan-Gutierrez was like them, wild.

But he should have reckoned, he chided himself, that a maincamper who would have had the nerve to come up here with them would not cower atop the hill waiting; with more nerve than sense, she would not stay put.

And Flanahan-Gutierrez was more than born-man, she had a father on Council; and a mother in the guards. That was more than trouble.

“Jane,” he called, plunging off the trail and into the most direct course through the mounds. It was twilight this low among the hills, deep dusk, so that he pushed his way blindly among the brush, for the moment losing his way, finding the trail again. “Jane!”

But he could see her with her anger and her born-man ways, just walking on, hearing his voice and ignoring it—determined to find her own way home. If she had started immediately after they had left the hill, she might almost have made it through the mounds by now, might be coming out among the hills just this side of town.

That was his earnest hope.

But the further he went, in the dark now, with sometimes the slither and hiss of calibans attending him—the more he feared, not for his safety, but for what an ignorant born-man might do out here at night. One could get by the calibans; but there were pits, and holes, and there were the Weirds like Green, who lurked and hid, who had habits calibans did not. Flitters troubled him, gliding from the trees. He brushed them aside and jogged where he could, out of breath now. “Jane!” he called. “Jane.”

No answer.

He was gasping and sweating by the time he reached the top of the last ridge, with the town and Camp in front of him all lit up in floods. He stood there leaning over, his hands on his knees, getting his breath, and as soon as the pain subsided he started moving again.

For a very little he would have given up his searching then, having no liking for going into the main Camp—for going to Gutierrez—Pardon, sir, has your daughter gotten home? I left her on the cliffs and when I got back she was gone . . . .

He had never seen Gutierrez angry; he had no wish to face him or Flanahan; but he reckoned that he might have no choice.

And then, when he had only crossed the fringes of the town, running along the road under the floodlights—“Hey,” a maincamper shouted at him: “You—did you come up from the azi town?”

He skidded to a stop, recognized Masu in the dark, one of the guards. “Yes, sir.” A lie, and half a lie: he had cut across the edge of it and so come up from the town.

“Woman’s missing. Out of bio. Flanahan-Gutierrez.—They’re supposed to be looking down in town. Are they? She went out this morning and she hasn’t gotten back. Are they searching out that way?”

“I don’t know,” he said, and the sweat he had run up turned cold. “They don’t know where she is?”

“Get the word down that way, will you? Go back and pass it.”

“I’ll get searchers up,” he said, breathless, spun about and ran, with what haste he could muster.

They would find out, he kept thinking in an agony of fear. The main Camp found everything out, whatever they tried to hide. They would know, and he and his brothers would be to blame. And what the main Camp might do then, he had no idea, because no human being had ever lost another. He only knew he had no wish to face her people on his own.

vi

The sun came up again, the second sun since Jane was gone; and Gutierrez sat down on the hillside, wiped his face and unstopped his canteen for a sip to ease his throat. They had gridded off, searchers in all the sections between the Camp and the cliffs and the Camp and the river. His wife reached him, sank down and took her own canteen, and there was a terrible, bruised look to her eyes.

The military was out there, in force, by pairs; and azi who knew the territory searched—among them the young azi who had come to him and Kate to admit the truth. A frightened boy. Kate had threatened to shoot him. But that boy had been out all the night and roused all the young folk he could find . . . had gone out again, on no knowing what reserves. It was not just the boy. It was Jane. It was the world. It had given her to them. But Jane thought in Gehenna-time; thought of the day, the hour. Had never seen a city. Had no interest in her studies—just the world, the moment, the things she wanted . . . now. Everything was now.

What good’s procedure? she would say. She wanted to understand what a shell was, what the creature did, not what was like it elsewhere. What good’s knowing all those things? It’s this world we have to live in. I was born here, wasn’t I? Cyteen sounds too full of rules for me.

The day went, and the night, and a new day dawned with a peculiar coldness to the light—an ebbing out of hope. His wife said nothing, slumped against him and he against her.

“Some run away,” he offered finally. “In the azi town—some of them go into the hills. Maybe Jane took it into her head—”

“No,” she said. Absolute and beyond argument. “Not Jane.”

“Then she’s gotten lost. It’s easy in the mounds. But she knows—the things to eat; the way to survive—I taught her; she knows.”

“She could have taken a fall,” his wife said. “Could have hurt herself—Might be too wet to start a fire.”

“All the same she could live,” Gutierrez said. “If she had two legs broken, she could still find enough within reach that she could get moisture and food. That’s the best guess; that she’s broken something, that she’s tucked up waiting for us—She’s got good sense, our Jane. She was born here, isn’t that what she’d say?”

They did it to bolster their own courage, shed hopes on each other and kept going.

vii

Jane screamed, came awake in the dark and stifled the outcry in sudden terror—the smell of earth about her, the prospect of hands which might touch . . . . But silence, no breathing nearby, no intimation of human presence.

She lay still a moment, listening, her eyes useless in this deep and dark place where they had brought her. She ached. And time was unimportant. The sun seemed an age ago, a long, long nightmare/dream of naked bodies and couplings in a dark so complete it was beyond the hope of sight. She was helpless here, robbed of every faculty and somewhere in that time, of wit as well.

She lay there gathering it again, lay there waking up to the fact that, having done what they had done, the Weirds were gone, and she was alone in this place. She imagined the beating of her heart, so loud it filled up the silence. It was terror, when she thought that she had long since passed the point of fear. She was discovering something more of horror—being lost and left. Isolation had never dawned on her in the maelstrom just past.

Think, her father would say; think of all the characteristics of the thing you deal with.

Tunnels, then, and tunnels might collapse: how strong the roof?

Tunnels had at least one access; tunnels might have more, tunnels meant air; and wind; and she felt a breeze on naked skin.

Tunnels were made by calibans, who burrowed deep; and going the wrong way might go down into the depths.

She drew a deep breath—moved suddenly, and as suddenly claws lit on her flesh and a sinewy shape whipped over her. She yelled, a shriek that rang into the earth and died, and flailed out at the touch—

It skittered away . . . an ariel; a silly ariel, like old Ruffles. That was all. It headed out the way Ruffles would head out if startled indoors . . . and it knew the way. It went toward the breeze.

She sucked in wind again, got to hands and knees and scrambled after—up and up a moist earth slope, blind, keeping low for fear of hitting her head if she attempted to stand. And a dim light grew ahead, a brighter and brighter light.

She broke out into the daylight blind and wiping at her eyes . . . saw movement then, and looked aside. She scrambled to her feet, seeing a human shape—seeing the aziborn young man crouched there, the first who had touched her. Alone.

“Where are the rest of them?” she asked. “Hiding up there?” There was brush enough, in this bowl between the mounds, up on the ridges, all about.

And then a sweep of her eye toward the left—up and up toward a caliban shape that rested on the hill, four meters tall and more—brown and monstrous, huger than any caliban she had imagined. It regarded her with that lofty, one-sided stare of a caliban, but the pupil was round, not slit. The feet clutched the curved surface and a fallen branch snapped beneath its forward-leaning weight as the head turned toward her. She stared—fixed, disbelieving when it moved first one leg and then the other, serpentining forward.

Then the danger came home to her, and she yelled and scrambled, backward, but brush came between her and it, and trees, as she climbed higher on the further slope.

No one stopped her. She looked back—at the caliban which threaded its way among the trees; again at the aziborn, who sat there placid in the path of that monster. Very slowly the young man got to his feet and walked toward the huge brown caliban—stopped again, looking back at her, his hand on its shoulder.

She began to run, up and over the mound—scrambling among the brush and the rocks. A gray caliban was there, down the slope and another—near her, that jolted her heart. It lashed about in the brush, caliban-like: it skittered down the slope and along the ridge, headed toward the river past the rocks—it must be going to the river . . . .

In a flash she realized where she likely was, near rocks that thrust through the mounds: rocks and the river below the cliffs.

She stopped running when she had spent her breath, slumped down amongst the trees and took stock of herself, her remnant of clothing, that she put to rights with trembling hands. She sat there in the brush with tears and exhaustion tugging at her, and she fought the tears off with swipes of a muddy hand.

“Hey,” someone said; and she started, whirled to her knees and half to her feet, like something wild.

From the Camp: they were two of the men from the Camp, Ogden and Masu. She stood up, shaking in the knees, and the blood drained from her face, sudden shame as she stood there with her clothes in rags and her pride in question. “There,” she yelled, and pointed back over the ridge, “there—they caught me and dragged me off—they’re there . . . .”

“Who?” Masu asked. “Who did? Where?”

“Over the ridge,” she kept crying, not wanting to explain, not wanting anything but to see it wiped out, the memory and the smiling, silent lot of them.

“Take care of her,” Masu said to Ogden. “Take care of her. I’ll round up the others. We’ll see.”

“There’s calibans,” she said, looking from one to the other of them. Ogden took her arm. Her coveralls were torn almost beyond staying on; she reached to cover herself and gasped for breath in shock. “There’s calibans—a kind no one ever saw—” But Ogden was pulling her away.

She looked back when Ogden had hastened her off with him. Fire streaked across the sky, and she stared at the burning star.

“That’s a flare,” Ogden said. “That’s Masu saying we found you.”

“There are people,” she said, “people living in the mounds.”

“Hush,” Ogden said, and squeezed her hand.

“It’s so. They live there. The Weirds. With the calibans.”

Ogden looked at her—old as her father, a rough man, and big. “I’m going to get you out of here,” he said. “Can you run?”

She caught her breath and nodded, shaking in all her limbs. Ogden seized her hand and took her with him.

But they met others, coming their way . . . and one was her father and the other her mother. She might have run to meet them: she had the strength left. But she did not. She stopped still, and they came and hugged her, her mother and then her father, and shed tears. She was dry of them.

“I’m going back after Masu,” Ogden said. “It may be trouble back there.”

“They should get them,” Jane said, quite, quite coldly. She had gotten her dignity back, had found it again, used it like a cloak between her and her parents, despite her nakedness.

“Jane,” her father said—there were tears in his eyes, but her own were still dry. “What happened?”

“They caught me and dragged me in there. I don’t want to talk about it.”

Her father hugged her, and her mother did. “Come home,” her mother said, and she walked with them, no longer afraid, no longer feeling anything but a cold distance between herself and what had happened.

It was a far way, to the Camp; and her father talked about medics. “No,” she said to that. “No. I’m going home.”

“Did they—?” That her mother found the question hard struck her as strange, and ominous. Her face burned.

“Oh, yes. A lot of times.”

viii

“There has to be law,” Gallin said, in Council, in the dome—looked down at all the heads of departments. “There has to be law. We rout them out of there and we have to do something with them. It was a mistake to sit back and let it go on. We can’t be having this . . . this desertion of the young. We set up fences; we organize a hunt and clear the mounds.”

“They’re our own kind,” the confessor-advocate objected, rising from her chair, grayhaired and on the end of her rejuv. “We can’t take guns in there.”

“We should,” Gutierrez said, also on his feet, “mobilize the town, dig foundations that go far down; we ought to make the barriers we meant to make at the beginning. We can shoot them—we can level the mounds—and it happens all over again. Time after time. It never works. There’s more going out there than we understand. Maybe another species—we don’t know. We don’t know their habits, their interrelations, we don’t know what drives them. We shoot them and we dig them out and it never works.”

“We mobilize the azi,” Gallin said. “We give them arms and train them—make a force out of them.”

“For the love of God, what for?” the advocate cried. “To march on calibans? Or to shoot their own relatives?”

“There has to be order,” Gallin said. He had gained weight over the years. His chins wobbled in his rage. He looked up at them. “There has to be some order in their lives. The tape machines are gone, so what do we give them? I’ve talked to Education. We have to have some direction. We make regiments and sections; we mount guard; we protect this camp.”

“From what?” Gutierrez asked. And added, because he knew Gallin, because he saw the insecure anger: “Sir.”

“Order,” Gallin said, pounding the table for emphasis. “Order in the world. No more dealing with runaways. No more tolerance.”

Gutierrez sank down again, and the confessor-advocate sat down. There was a murmuring from the others, an undertone of fear.

The calibans had come closer and closer over the years and they had found no occasion to say no.

But he had qualms when he saw the azi marshalled out for drill, when he saw them given instruction to kill. He walked back on that day with a lump in his gut.

Kate and Jane met him, daughter like mother—so, so alike they stood there, arms about each other, with satisfaction in what they saw. A change had come about in Jane. She had never had that hard-eyed look before she went out into the mounds. She had grown up and away, to Kate’s side of the world. No more curiosity; no more inquiring into the world’s small secrets: he foresaw silence until that threat out there was swept away, until Jane saw the world as safe again.

While azi marched in rows.

ix

Pia Younger set the bucket down inside the door, in the two room house that was theirs, a house hung with clothes and oddments from the rafters—drying onions, dried peppers, plastic pots balanced on the beams, and her own bed in this corner, her parents’ bed in the other room. And rolled pallets that belonged to her brothers, who prepared for another kind of leaving.

Her mother sat outside—a woman of silences. She went out again and stopped to take her mother’s hand, where she sat sharpening a hoe—stroke, stroke of a whetstone across the edge. Her father—he was off with the boys. Her mother paid little attention . . . had paid little at all to the world in recent days. She only worked.

“I’m going out,” Pia Younger said. “I’m going to see how it goes.” And quietly, in a hushed voice, bending close and taking her mother’s hands: “Listen, they’ll never catch Green. They’ll go up the river, all the lost ones do. Don’t worry about them shooting him. They can’t.”

She felt guilty in the promise, having no faith in it, having no love for her brother. And it all failed with her mother anyway, who went on with her sharpening, stone against steel, which reminded her of knives. Pia drew back from Pia elder and as quietly drew away. She lifted her eyes to the borders of the town, where another kind of camp was in the making.

Her father was out there following born-man orders; her brothers pretended to. And very quietly, Pia elder never noticing, Pia Younger walked down the street the opposite way, then cut through at the corner and doubled back again.

She watched the weapons-practice from the slope of the caliban-raised hill near the town, crouched there, as she daily watched these drills. The fields went unattended; the youngest deserted the work. And she knew what her brothers said among themselves, that they would only pretend, and carry the weapons, but when it got to attacking the calibans and runaways, they would run away themselves. Her father did not know this, of course. Her father carried arms the way he did other things the officers asked of him. And that was always the difference.

Herself, she sat thinking on the matter, how drear things would be if her brothers should go, if all their friends should follow them.

Sixteen years was almost grown. She sat making up her mind, thinking that she would go already if not for the danger of the guns and the weapons, that they might mistake her for one of the Weirds out there. Her parents would not understand her leaving. But they understood nothing that was different from themselves; and she had known long ago that she was different. All the children were.

Most of the day she watched; and that night her brothers did not come home. Her father came; neighbors came. They waited dinner. The blanket rolls waited against the wall. And her parents sat in silence, ate finally, asked no questions even of each other, their eyes downcast in that silence in which her parents suffered all their pain.

Officers came in the night, rapped on the door and asked questions—wrote down the names of her missing brothers while Pia hovered behind her parents, wrapped in her blanket and shivering not from cold, but from understanding.

x

“We have to move,” Jones said—atop the hill, where they had set up the observation post; and Kate Flanahan nodded, looking outward over the mounds. She shifted her fingers on the woven strap of the gun she carried on her shoulder. “We’ve got the location of the runaways: we’re getting radio from Masu and his lot, with the site under observation. We get this settled. Fast. We’ve turned back two hundred deserters at the wire—it’s falling apart. We get the human element out of this thing, get those runaways routed out of there before we have every aziborn in town headed over the hill. They’re deserting in troops—got no sympathy for this operation; and there never was any need of drafting that many. This unit: Emberton’s up the way—we’ll get it stopped. No more runaways then; and then we can get the older workers to start building that barrier. Any questions before we move?”

There were none. Flanahan had none; had hate—had that, for her daughter’s suffering, for the hush that had fallen on Jane, the loss of innocence. For her daughter who sat inside or fell to the studies which she had always hated, because it filled her mind.

“Move out,” Jones said, and they moved, filed out quietly through the hills, amid the brush and the trees of the mounds. Some of Bilas’ crew brought the demolitions. Vandermeer had a projectile gun, and gas cannisters to flood the mound and make it unpleasant for the refugees. And a few shots after that—

The orders were not to kill. But Flanahan reckoned that accidents might happen; there might be excuse. She was looking for one.

They walked, moving cautiously, making as little disturbance as possible . . . but the way they knew, had it down precisely—the spot where Emberton’s unit had set up shop, watching the accesses, watching the runaways come and go.

They came on a sentry: that was Ogden, one of their own—and gathered him up into their small band: eight of them, in all, counting borrowings from Maintenance—and Emberton was arriving with her escort a little earlier, to take personal command up on the ridge. From now on it was careful stealth: and they broke as few branches as possible, disturbed the brush only where they had to. Flitters troubled them, brushed aside when they would light and cling. A fevered sweat ran on Flanahan’s arms and body—a chance, finally, to do something. To take arms against the confusion that had marked all their efforts in Gehenna. A few shots fired, a little healthy fear on the part of the aziborn: that would settle it.

And then they might build again.

Flanahan was breathing hard when they topped the ridge: the gun was no small weight and she was years out of training. So were they all—Jones with his waist twice its former girth; Emberton gray with rejuv. She saw the tactical op chief in conference with Masu and Tamilin and Rogers as they came up, into that area where Masu and Kontrin and Ogden had sat out observing the situation throughout.

The runaways were still there. Kate Flanahan crept up with the others, near the edge. The word passed among their crouching ranks. Vandermeer armed the projectile gun with the gas cannisters, aimed at the access of the mound they faced. And right in front of them a pair of the fugitives sat naked, sunning their bony, muddy limbs.

Of the calibans, no sight; and that was just as well: less confusion. Jones put the safety off his rifle, and Flanahan did the same, the sweat colder and heavier on her with the passing moments. Those ragged creatures down there, those fugitives from all that was human, they had hurt Jane . . . had humiliated her; had cared nothing for what they did, for their pleasure; and Jane would never be the same. She wanted those two. Had one all picked out.

“Move,” the order came from Jones; and they did as they had arranged, pasted a few shots near the visible fugitive, came down the slope. Flanahan whipped off a shot, saw the taller of the two go down like he was axed.

And then the ground pitched underfoot, went soft, slid: there were outcries. One was hers. Trees were toppling about them. Of a sudden she was waistdeep in earth and still sliding down as the whole slope dissolved.

She let go the rifle, used her hands to fight the cascading earth; but it went over her, pinning her arms, filling her mouth and nose and eyes; and that and the pressure were all, pain and the crack of joints.

xi

So they failed. Jane Flanahan-Gutierrez understood that when her father came to her to break the news . . . but she had understood that already, when the radio had been long silent, and the rumor went through the Camp. She took it quietly, having abandoned the thought that her life would proceed as she wanted. Little surprised her.

Her father settled into silence. His calibans went unhunted, after all; but Kate was gone, and calibans had killed her. He smiled very little, and a slump settled into his shoulders in the passing months.

He offered to have the doctors rid her of it, the swelling presence of the child in her belly; but no, Jane said, no. She did not want that. She paid no attention to the stares and the talk among the youths who had been her friends. There was herself and her father; there was that . . . and the baby was at least some of Kate Flanahan; some of her father, too; and of whatever one of the lostlings had sired it.

When it came she called her daughter Elly—Eleanor Kathryn Flanahan, after her mother: and her father took it into his arms and found some comfort in it.

Jane did not. Jin’s daughter, it might be; or one of his brothers’. Or something that had happened beneath the hill. She fed it, cared for it, saw a darkhaired girl toddling for her father’s hands, or going after him with smaller paces, or squatting to play with Ruffles—at this she shuddered, but said nothing—Elly followed her grandfather everywhere, and he showed her flitters and snails and the patterning of leaves.

That was well enough. It was all Jane asked of life, to keep a little peace in it.

The fields went smaller. The azi who had fled did some independent farming, over by the cliffs, so the rumor ran. Gallin died, a cough that started in the winter and went to pneumonia; that winter carried off Bilas too. They went no longer outside the Camp—the calibans came here, too . . . made mounds on the shore, between them and the fishing; and only that roused them to fight the intruders back.

But the calibans came back. They always did.

Jane sat in the summer sun the year her father died, and saw Elly half grown—a darkhaired young woman of wiry strength who ran with azi youths. She cared not even to call her back.

That was the way, at the end of it all, she felt about the child.

xii

Year 49, day 206 CR

There were more and more graves—of which the born-man Ada Beaumont had been the first. Jin elder knew them all: Beaumont and Davies, Conn and Chiles, Dean who had birthed his son; Bilas and White and Innis; Gallin and Burdette, Gutierrez and all the others. Names that he had known; and faces. One of his own sibs lay here, killed in an accident . . . a few other azi, the earliest lost, but generally it was not a place for azi. Azi were buried down by the town, where his Pia lay, worn out with children; but he came here sometimes, to cut the weeds, with a crew of the elders who had known Cyteen.

So this time he brought the young, a troop of them, his daughter Pia’s children and three of his son Jin’s; and some of Tam’s, and children who played with them, a rowdy lot. They trod across the graves and played bat-the-stone among the weeds.

“Listen,” Jin said, and was stern with them until they stopped their games and at least looked his way. “I brought you here to show you why you have to do your work. There was a ship that brought us. It put us here to take care of the world. To take care of the born-men and to do what they said. They built this place, all the camp.”

“Calibans made it,” said his granddaughter Pia-called-Red and the children giggled.

“We made it, the azi did. Every last building. The big tower too. We built that. And they showed us how, these born-men. This one was Beaumont: she was one of the best. And Conn—everyone called him the colonel; and he was stronger than Gallin was . . . Stop that!” he said, because the youngest Jin had thrown a stone, that glanced off a headstone. “You have to understand. You behave badly. You have to have respect for others. You have to understand what this is. These were the born-men. They lived in the domes.”

“Calibans live there now,” another said.

“We have to keep this place,” Jin said, “all the same. They gave us orders.”

“They’re dead.”

“The orders are there.”

“Why should we listen to dead people?”

“They were born-men; they planned all this.”

“So are we,” said his eldest grandson. “We were born.”

It went like that. The children ran off along the shore, and gathered shells, and played chase among the stones. Ariels waddled unconcerned along the beach, and Jin 458 shook his head and walked away. He limped a little, arthritis setting in, that the cold nights made worse.

He worked in the fields, but the fields had shrunk a great deal, and it was all they could do to raise grain enough. They traded bits and pieces of the camp to their own children in the hills—for fish and grain and vegetables, year by year.

He walked back to the camp, abandoning the children, avoiding the place where the machines that had killed Beaumont rusted away.

Some azi still held their posts in the domes, and the tower still caught the sun, a steel spire rising amid the brush and weeds. Flitters glided, a nuisance for walkers. Ariels had the run of all the empty domes in maincamp, and trees grew tall among the ridges which had advanced across the land, creating forests and grassy hills where plains and fields had been. Most of the born-men had gone to the high hills to build on stone, or their children had. In maincamp only the graves had human occupants.

He was old, and the children went their own way, more and more of them. His son Mark was dead, drowned, they said, and he had not seen the rest of his sons in the better part of a year. Only his daughter Pia came and went from them, and brought him gifts, and left her children to his care . . . because, she said, you’re good at it.

He doubted that, or he might have taught them something. The shouts of children pursued him as he went; they played their games. That was all. When they grew up they would go to the hills and go and come as they pleased. Himself, he kept trying with them, with life, with the world. This was not the world born-men had planned. But he did the best he knew.