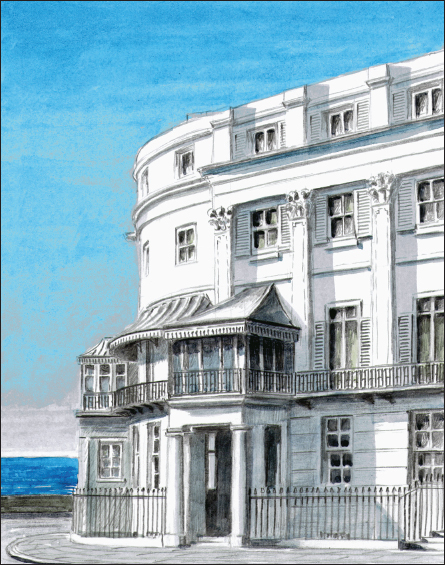

FIG 1.1: White stuccoed terraces from Brighton, the most notable of Regency resorts.

For my generation, it is hard to write a book about the Regency period without conjuring up images of Hugh Laurie’s portrayal of the Prince Regent in T.V.’s Blackadder III. His self-centred, dim-witted and unpopular character which made such a mockery of late Georgian life was based upon some elements of truth. The actor was probably relieved to learn, however, that an accurate representation of the Prince Regent’s size was not required for the role since the Prince of Wales weighed nearly 18 stone by the time he was thirty years old and developed a 50-inch waist during his reign as king.

Unfortunately, over-eating was the least of his problems. As the eldest son of George III, the young prince, influenced by radical friends, quickly gained a reputation for being extravagant with money, leading a disreputable life of excessive drinking and gambling and for having a string of mistresses, one of whom he even secretly married. By 1795 he had amassed a personal debt of around £50 million in today’s money and, as part of a deal to pay it off, Parliament and his father, the king, forced him to marry his cousin, Princess Caroline of Brunswick.

Their relationship was a disaster and after only one year together, they lived separately, both having affairs. In 1814 Caroline left England and not until her husband became king six years later, did she return in order to assert her rights as Queen Consort. On the day of the coronation, though, she fell mysteriously ill and died shortly afterwards.

Despite their unhappy union, they did manage to have a child, Princess Charlotte, who unlike her father became a popular figure and carried the hopes of a nation disillusioned with the prince. There was much anticipation when she married Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld and was expecting a child.

However, tragedy struck at the birth when both mother and child died. This plunged the country into weeks of mourning and deprived the Prince of Wales of a legitimate heir. The press made much of this fact, encouraging his unmarried brothers to do their duty, an idea seized upon by Prince Edward, the Duke of Kent and Strathearn. He promptly removed his mistress and married the sister of Prince Leopold who produced a daughter, the future Queen Victoria.

FIG 1.2: The Prince Regent, later George IV, was a driving force behind new architectural styles, initiating the redevelopment of large parts of central London. He was also credited with changing the face of fashion. He began to wear his hair loose, after a government tax was put on wig powder; promoted the wearing of dark colours and loose trousers (as they best disguised his weight); and embraced the fashion for high collars and neck cloths as they hid his double chin!

The Prince of Wales’ relationship with his father was equally strained. Despite the country’s growing affection for George III, his bouts of madness were of grave concern. The first notable occurrence in 1788 resulted in Parliament introducing a Regency Bill, only for the king to recover before it could be passed. (This crisis was the subject of the play and film The Madness of King George). In 1810, when his condition deteriorated once again upon the death of his youngest daughter, Parliament had no choice but to reintroduce the bill and the Prince of Wales became Prince Regent on 5th February 1811. After nine years of the Regency, the king finally passed away and the prince was crowned George IV, reigning for a further ten years until his death in 1830.

Contemporary obituaries made much of his poor character, inappropriate expenditure and lack of popularity. His humorous and intelligent nature was let down by drinking and laziness. There was one area, however, in which many commentators thought he had merit and that was as a gentleman of taste and a connoisseur of the arts. He not only established fashions in clothing and personal appearance but also promoted numerous building projects in an architectural style that has since become distinctive of the Regency period.

Although the Prince Regent’s governance of the country during his father’s final illness lasted less than ten years, the term ‘Regency’ has been more generally applied to the first three decades of the 19th century. This is mainly because there were key changes in society and fashions which marked out this late Georgian period from its early and mid phases. In architecture, though, the term ‘Regency’ encompasses an even larger timescale. The style and form of building championed by the Prince have their origins in the 1780s, and the distinctive form of terrace developed during this period was still being erected in the 1840s. Therefore, although this book will concentrate on houses built from around 1800 through to the 1830s, there will be examples of those Regency styles introduced in the decades before and some which were a late flowering.

Despite the impression of the Regency period being one of frivolity, elegance and leisure, the country actually spent most of this time at war, or recovering from its aftermath. Defeat in the American War of Independence in 1783 had a devastating effect on George III and resulted in the raising of taxes to pay for the expense of running a campaign so far from home. Of greater influence, however, were periods of warfare which began only a decade later with France. The first phase is referred to as the French Revolutionary Wars (1793–1802), with the resumption of the conflict being known as the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815). Britain’s dominance of the seas led to victory at the Battle of the Nile, hampering Napoleon’s occupation of Egypt, and at Trafalgar in 1805 which ended his chances of invading England from across the Channel. Napoleon therefore turned his attention to victory in Europe which he had largely achieved by 1808. He then set about closing ports to British trade causing bankruptcies, riots and industrial unrest here, although France suffered similarly and the policy was dropped by 1812. Napoleon’s eventual defeat at Waterloo in 1815 resulted in territorial gains and increased trade which helped boost Britain’s wealth and the expansion of its fledgling empire.

Pitt the Younger, the wartime prime minister until his death in 1806, had not only provided stability during this period but had also introduced measures to ensure posts were filled by officials appointed on merit and not favour, thus helping to establish a professional civil service and permanent government. The ruling classes also had to deal with the underlying threat of revolution from below throughout this period. Although they did not make any dramatic concessions, the Reform Act of 1832 gave the burgeoning middle classes a chance to vote which defused some of the pressure. The gentry became aware of the poor image which they projected to the nation and began to cast themselves publicly in a more dignified and patriotic light. Gone were frivolous French fashions and powdered wigs, now it was grey and black formal dress and military uniform. Despite poor living conditions, lack of employment for the huge influx of returning soldiers in 1815 and the threat to jobs from new machines, the labouring classes never quite united in sufficient numbers to force revolution and so they generally supported the war effort.

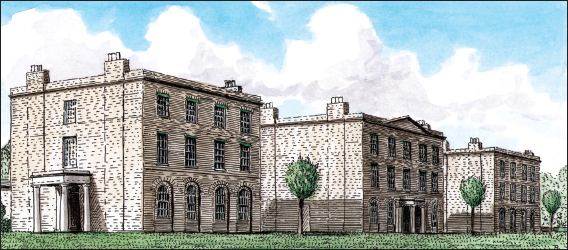

FIG 1.3: WEEDON, NORTHANTS: These three brick buildings, later known as the Pavilion, were built for the governor and two principal officers at the same time as the neighbouring ordnance depot. Shortly afterwards, however, they were earmarked for use as a residence for King George III should Napoleon invade since Weedon was virtually the furthest point inland from any coast. Although these houses have since been demolished, much of the depot still stands.

FIG 1.4: PARK CRESCENT, LONDON: During this period, some of the most iconic buildings were erected and large parts of central London rebuilt. The most notable scheme was the forming of Regent Street and Park by John Nash for the Prince Regent, including the crescent in this view. Further out, rows of fashionable new terraces were built as urban residences for the wealthy and, increasingly, for the growing number of professionals who now included permanent and wage-earning civil servants.

From the middle of the 18th century the population of Britain began to rise. The reasons for this significant, long-term increase are still debated but by the time of the first census in 1801, the total number of people in England had risen to over 8 million (16 million for Great Britain and Ireland), growing to around 14 million (26 million for Great Britain and Ireland) by the time Victoria came to the throne in 1837. London was the largest city by far, with a population of one million at the turn of the century, nearly doubling by 1840. Although in 1801, the nearest to it in numbers had barely 100,000, major cities like Manchester, Liverpool, Birmingham, Leeds, Glasgow and Bristol had boomed by the end of the period with populations from between 120,000 to 250,000.

Upper class landowners benefited most. Those who were forward thinking developed their country estates into more efficient farmland, extracted its mineral wealth and established industries upon them, while developing their urban estates and making a fortune from property. They married within their class as much as possible and sent their sons into politics, the Church or the army. They did not split their estates upon their death and so maintained a firm grip on their assets. Life was not always a ball, though. Gambling and drinking were well-known vices and many went bankrupt as a result, while they were often a target of crime and disorder, with locks and shutters a reminder of the measures they had to take to protect their property. Despite the high profile of this class in historic records and contemporary literature, they only represented a tiny proportion of the population. Those with incomes of over £1,000 a year only numbered in the low thousands at the turn of the century.

Below them professionals ranging from doctors, lawyers, bankers, civil servants, clergymen and farmers down to managers, shopkeepers, tradesmen and soldiers, together with others who grew rich on trade and industry, were a rapidly growing group. Initially, they were still subservient to their social superiors but became a more confident middle class by the end of the period. Most of the housing which survives from this time was built for this diverse and fluid class, yet their total number probably only represented around 10%–15% of the population.

The vast majority comprised the labouring classes who had no vote, unreliable incomes and homes which ranged from adequate to inhumane hovels. At the beginning of the 19th century, around four out of five people worked on the land but 50 years later it was only half, as the rapid exodus from the countryside created urban slums made worse by the migrants bringing their livestock with them. A growing number worked in domestic service, (around 750,000 by the 1830s), with the wealthiest families having an army of servants which could number in the hundreds, whilst a lesser gentleman might have just four or five.

Much of the new housing erected in this period was the direct result of developments in transport and industry. Turnpike trusts had gradually improved the road network such that coach travel became faster and more reliable, with inns, hotels and stables erected to service this trade. Most well-to-do families had one or more of a wide range of different carriages and coaches. Therefore, mews, coach houses and stables were an important consideration when building or choosing a house. Canals and river navigations enabled large quantities of goods to be moved from far inland to the ports which, in turn, rapidly developed. Many settlements grew up around wharfs and boatyards, while those who grew rich on trade, merchant shipping and the running of the ports moved into elegant housing away from their place of work.

FIG 1.5: CLIFTON, BRISTOL: This major sea port grew rich on colonial trade, and successful merchants and ship owners moved into fashionable new terraces built on the hills at Clifton overlooking the docks. These sometimes huge rows and crescents still survive today, with most of their period fixtures and fittings intact, and represent one of the finest collections of Regency housing in the country.

What we now term as the Industrial Revolution was a gradual development, with its seeds sown in Tudor England and its full flowering in the Victorian period. Although it was rapidly altering the face of many areas of the country in the early 19th century, there were parts where it barely touched. Most factories and mills were small scale, with much of the process of production still carried out at home. The impetus for change did not come from the landed gentry, although some were quick to jump on board, but from entrepreneurs. These were often Quakers, Methodists or yeomen who had become successful by embracing new technology and forcing their own ethics of hard work and discipline on their workforce. They built themselves fine houses while those within the company who had risen to become supervisors or skilled technicians could earn in a week what some labourers and maids were paid in a year. In whatever trade you were during this period, however, your income could vary according to the seasons, wars, the availability of supplies and the whims of your employer.

FIG 1.6: EDENSOR, DERBYS: New villages were often created during the Regency period when parkland was laid out around a country house and the old settlement removed so as not to spoil the view as was done here at Edensor on the Chatsworth estate. Joseph Paxton (later designer of the Crystal Palace) and John Robertson designed the new village from the late 1830s, with the myriad of styles based upon those of J.C. Loudon whose Encyclopedia of Cottage, Farm, Villa Architecture, 1834 was highly influential at the time.

The way people spent the money they earned began to change from the late 18th century. For the majority of the population, holidays, as we know them today, did not exist. People did not travel outside their local area but instead relied upon visiting fairs, wakes, and other seasonal events for their entertainment. Wealthier families, though, had far greater choice. They could enjoy trips to the theatre, to the assembly rooms, visit spas and have holidays at the seaside. The taking of medicinal waters was an opportunity to cleanse the body and be entertained. A visit by a member of the royal family to an unassuming spring often initiated a wave of new housing, hostelries, theatres, and shops, thus resulting in the creation of a new spa town. It was also believed by some doctors that bathing in and even drinking sea water was good for one’s health and a number of resorts for the wealthy began to develop. It is in the Regency spa towns of places like Cheltenham and Leamington and seaside resorts most notably Brighton, therefore, where some of the finest housing from the period can be found.

Many of the buildings in our cities and town centres today began to appear or develop on a large scale during the early 19th century as the growing middle classes and more mobile gentry were encouraged to spend money on fashion and entertainment. New shops began to line the high street, with larger panes of glass through which to view the products, as for example in London where Oxford Street began to attract leading manufacturers to establish stores in which to display their goods. Banks, shopping arcades, theatres, halls and assembly rooms were built or rebuilt; offices, factories and mills were erected; and new municipal structures like town halls, prisons, court rooms and workhouses became dominant features within the urban landscape. As public institutions became permanent fixtures and employment focused on new areas so the demand grew for new housing. Hotels and luxurious apartments were built at seaside resorts and spa towns, whilst spacious villas and tall terraces for the well-to-do were erected in the new industrial cities and ports, and formal squares and elegant streets developed in the capital to cope with its rapid expansion.

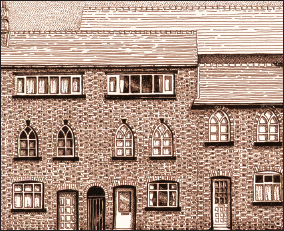

FIG 1.7: LEEK, STAFFS: This row of houses was built in the 1820s, with Gothick pointed windows with ‘Y’-shaped glazing bars and grey and red chequered brickwork which is distinctive of the Regency period. At this date, much of the production process of cloth was carried out by workers in their own homes and these houses had characteristic long attic windows to illuminate the weaver’s work; large mills where all the production took place were to develop later.

FIG 1.8: CHELTENHAM, GLOS: Possibly the finest collection of Regency housing can be found in this famous spa town which saw rapid development after a visit by King George III in 1788. Over the following fifty years, rows of magnificent terraces and villas were erected by speculative builders around the various pump houses in which wealthy patrons took the waters, while more modest terraces for those who serviced this leisure town still survive on its outer edge.

FIG 1.9: SCARBOROUGH, YORKS: This famous holiday destination developed in the early 18th century as an exclusive spa and became the first seaside resort, with elegant houses like The Crescent pictured here built in 1833.

With such a diverse range of new buildings and sources of inspiration coming from ever more distant countries and times, combined with the availability of a wealth of new materials, the architecture of Regency Britain had a refreshing variety missing from the earlier more formal Georgian period. This sometimes extraordinary, eclectic mix of styles was best seen on the country houses, urban mansions and holiday retreats for the rich. These large houses, designed by leading architects, represent the key character of Regency style.

FIG 1.10: GREY STREET, NEWCASTLE UPON TYNE: This most celebrated of British streets, with its imposing Regency buildings subtly curving down towards the river, was developed from the 1820s by Robert Grainger. It was named after Prime Minister Earl Grey who oversaw the passing of the 1832 Reform Act and whose monument stands at the top of the street.