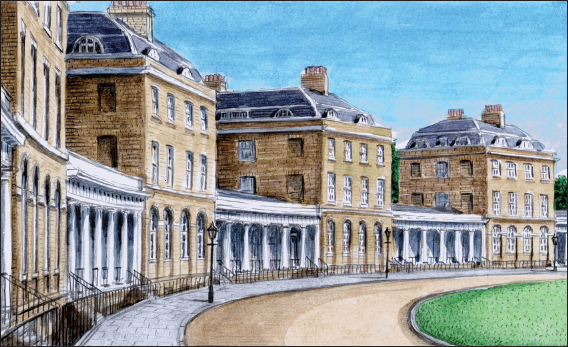

FIG 3.1: Eaton Square, London, was a speculative development by Thomas Cubitt.

The wide variety in the form and style of architect-designed houses was less noticeable in the mass market of speculative-built terraces and semis. The finished home would nearly always be rented out and with the limited funds of most builders they could not afford to have property sitting vacant. Therefore they tended not to take any risks with the design. It had to be fashionable but not controversial, so exotic and historic forms were limited to decorative details, while the main body of the terrace was laid out to a familiar plan.

However, from the 1820s onwards, more ambitious schemes were common in fashionable resorts and cities, where a long row, square or crescent could be planned as a complete piece. Some were arranged with an outline which mimicked a large country house in what are termed palace-fronted terraces. New detached and semi-detached villas, compact urban versions of the small country houses which had been popular in the late 18th century, were also built. These had distinctive stepped back, single-storey wings or porches to the sides and shallow hipped roofs above. These large-scale projects could make a builder a fortune, like Thomas Cubitt who erected much of Belgravia in London. However, it could bring others to near ruin like Michael Searles who designed the Paragon in Blackheath.

FIG 3.2: Examples of terraces from Bristol (above left), Liverpool (above right) and a crescent from Shrewsbury (opposite) all dating from the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The ironwork balconies are very distinctive of the period. The horizontal bands running along the window cills were popular in some areas, while other façades were notably plain.

FIG 3.3: As you walk along a terrace like this, it appears all of one build. However, when you step back and look closely, you can see by the steps in the cornice and parapet along the top that, as with most developments at the time, it was built in sections at different times and/or by different builders.

FIG 3.4: As with most terraces of this date, the above example has the front doors raised up a short flight of steps, with the main entertaining rooms marked by the tallest windows on the first floor or piano nobile (as the hallway made the ground floor rooms narrower). It was common for the entrance to be on the same side of each house as to the left in this terrace. However, placing them together in pairs, as seen to the right in this view, was popular in certain areas and became standard on most terraces and semis in the Victorian period.

FIG 3.5: Some large-scale terraces which were planned as one complete project were designed to appear like a large country house. These palace-fronted terraces, as they are known, could have the central and end sections brought slightly forward as in this early 19th-century example (above) where they are highlighted with window guards and pilasters, or could have a large pediment fitted in the middle as in the terrace from the late 18th century (left). Note that the chimneys hidden behind the parapet are rectangular and plain.

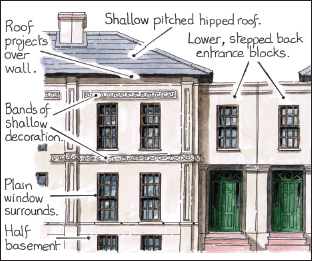

The terrace with its efficient use of land was still far and away the most popular form of urban housing. A Regency terrace of any pretensions had a half basement with a flight of steps leading up to the front door; on earlier Georgian types they were usually level with the ground. They also tended to be taller as ceilings became higher and builders more ambitious, with some monster rows five or six storeys high. The façade was still controlled by Classical rules and orders so window openings were of calculated proportions and the horizontal division of the façade reflected that of ancient temples. With the fashion for the Neo Classical, it was usually a sharp-edged box with little raised surface decoration. However, attitudes were relaxing and builders were happy to mix up sources of architectural details and periods or copy some of the more playful elements designed by contemporary architects. Large relieving arches recessed in the brickwork, bow windows, and sections stepped back around the front door are often found. Later in the period, mouldings around windows, full-height pilasters (flat columns fixed to the wall) close to the corners, and decorative bands carved out of stone or formed in stucco begin to appear as a precursor to the more decorative and eclectic styles of the Early Victorian period.

FIG 3.6: A Regency-style villa, with a distinctive shallow-pitched hipped roof covered in slate. It has deep overhanging eaves, a stuccoed exterior (originally in a stone colour) and round arched windows on the ground floor implying an arcade (row of arches). The thin border around the edge of the upper sash windows are margin lights which were popular in this period.

FIG 3.7: THE PARAGON, BLACKHEATH, LONDON: This imposing crescent was built by Michael Searle from 1794–1807 as a series of paired houses in stone-coloured stock bricks linked by low colonnades covered in stucco and featuring Coade stone decorative parts. As with most houses already featured, these were luxury homes which, in this case, the builder would customise to suit the occupant. Unlike late Victorian houses, they were designed close up to the street so one could see out and also be seen by those promenading outside.

FIG 3.9: A Regency semi, with labels of its distinctive features. This was a relatively new form of house and had distinctive low and stepped back entrances to the sides.

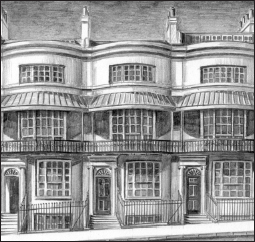

FIG 3.10: Bow or elliptical fronted houses or windows were a fashionable feature of Regency houses, especially at seaside resorts where they permitted residents a better view of passers-by and the coastal landscape, as in these examples from Brighton. Some were just tall bays added onto an otherwise plain façade, others had the whole front bowed.

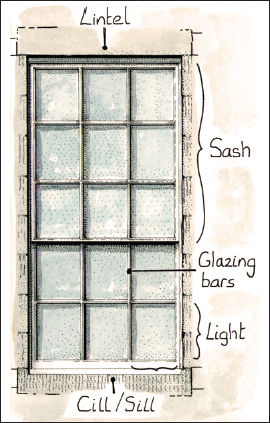

Builders did not have a free reign in the design of terraces, semis and detached houses; their form was increasingly shaped by regulations and taxation. A number of building acts had been introduced in the capital since the Great Fire of London and had gradually been adopted in other towns and cities. Legislation introduced in 1774 was designed to not only make houses more fire-proof but also to raise the standard of construction across the country as a whole. In order to stop flames spreading along the fronts of houses, the ban on timber decorative parts on the façade was reinforced and sash window frames had to be recessed behind the brick reveal. Inadvertently, this made them appear more elegant and refined, especially as the size of the panes of glass increased and glazing bars became thinner by the early 1800s. There were also restrictions on how far a bay window could project onto a street, and distinctive shallow bow windows became popular in the Regency period.

FIG 3.11: The 1774 Building Act set the frame of sash windows behind the outer wall, in part creating the elegant types as here which became distinctive of the Regency period.

At the same time, builders had to cope with increased taxation introduced to raise funds in the wake of the American War of Independence and during the Napoleonic Wars. A brick tax was introduced at a rate of 2s 6d per 1,000 bricks, rising to five shillings in 1803. This encouraged the use of slightly larger bricks in some areas and the introduction of rat trap bond brickwork, with bricks stacked up on their thinner sides. The number of windows a house could have before being taxed was also reduced so that more houses came within the scope of the window tax. The blocking up of openings to escape the tax was common practice although many bricked-up windows found today are ones that were original features and were altered to free up wall space inside while maintaining symmetry outside or were bricked up due to later changes to the layout of rooms.

Despite the efforts of architects and regulators, building standards were notoriously lax during this period. This was partly due to high costs and poor supplies of materials, especially during the early 1800s. Also, though, leases of under one hundred years and low returns on rent did not encourage the erection of houses designed to last centuries. It was also hard to tell that corners had been cut as it was acceptable in this period for the exterior of the building to be covered with a cladding or render imitating a finer material; a deceit which riled later Victorian Gothic architects. Many Regency houses that have survived through to the present day are due to the combined support of being built in a long row rather than because of their individual quality; and collapses are not unknown. There is good reason why the term ‘jerry building’, from a nautical phrase meaning ‘temporary rigging’, was first coined in this period.

FIG 3.12: Ashlar, fine jointed masonry (left), was desirable. If it wasn’t affordable, then stucco, incised with lines and moulded to create carved details (centre), was a popular alternative. In some cases, both were used (right) or stucco was applied just to the lower storey of a brick house.

Stone was the building material of choice yet, despite industrial progress and improved transport, it was an expensive product and still limited to the local area for all but the finest houses. Limestone and sandstone were cut into squared off blocks and laid with the finest of joints to create as near a smooth finish as possible (ashlar), with the ground floor of some having the joints opened up into deep chamfered grooves (rustication). In areas where stone was not a cost-effective option or on projects which did not justify the expense, the Regency acceptance of imitation came to the fore.

Stucco had been a term which referred to all plasterwork inside and out but, by the early 1800s, had become more specifically the rendering used to cover the exterior of brick houses in order to make them appear to be constructed of stone. The surface was built up in a number of layers and then had fine grooves scoured into the wet surface to mimic the joints in masonry. The finished work was painted in the colour of fashionable stone, generally beiges and greys, although other colours were sometimes recommended; while the joints could be highlighted with grey shadow. The bright white and cream with which most have been repainted are a later 19th-century fashion. The colour which was chosen was also applied across the whole terrace. The aim of trying to make the buildings appear as one large noble house is lost today, with individual properties painted in an assortment of different colours.

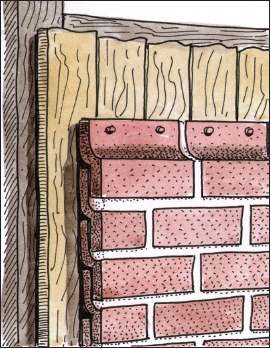

Although brick exposed on the façade had fallen from fashion in London and many other cities in the second half of the 18th century, there were still areas where covering it in stucco did not catch on. With developments in brick production, a larger range of colours was now available and bricks of the same hue as stone were often used with fine joints and mortar which could also be painted to match. In some towns, though, red brick was still acceptable except it usually had the distinctive addition of vitrified grey headers inserted to make a chequered pattern across the front of the house. In Kent and Sussex, timber frames were covered with hanging tiles which were formed so that they created a smooth vertical surface which imitated brickwork. These mathematical tiles became popular in other areas, mainly in the south, during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The effect can be very convincing from the front but if the corners are exposed, then there is some form of vertical strip to cover up the joint.

FIG 3.13: Chequered patterns formed from two different coloured brick, usually with grey vitrified headers (the small ends of bricks) within a good quality, regular-sized local brick are distinctive of the Regency period. This finish can still be found in towns where stucco was only partially adopted or never caught on. These decorative finishes were only applied to the front, with cheaper bricks used down the sides and rear.

FIG 3.14: Iron balconies, as in these highly decorative types pictured here, and smaller window guards are the most visible use of new mass-produced metals in Regency houses.

The production of iron on an industrial scale now meant it was available to the house builder for structural work rather than just for decorative purposes. It is most visually present in balconies which are distinctive of the period: ironwork frames with delicate cast railings, brackets and posts, with Chinese pagoda-style roofs on top. However, iron could also be found within some buildings as beams across the house, with the ends cantilevered out to support staircases or balconies. Metal could also be used to make windows, glass roofs and conservatories, with thin rods inserted in wooden glazing bars to allow them to become thinner still.

FIG 3.15: Mathematical tiles could be applied to old or new houses by pinning them to timbers and then mortaring in the gaps so they appeared like brick. They could be glazed in a number of different colours.

FIG 3.16: With timber being banned and carved stone expensive, an artificial stone manufactured by Eleanor Coade became popular in the late 18th and early 19th centuries for decorative mouldings and figures on the exterior of houses. It was a form of ceramic which has proven to be extremely durable and the ‘Coade’ stamp in the pieces they made at their Lambeth works is usually still clearly identifiable today as in this example from 1805 (when the company was known as Coade & Sealy).

FIG 3.17: Below the first and second rate houses as defined by the 1774 Building Act (based upon their floor area and cost) were third and fourth rate terraces as in these fine examples from Bristol, Liverpool and Cheltenham.

Another distinctive characteristic of Regency housing was shallow pitched slate roofs (see Figs 3.6 and 3.9). Welsh slate which could be broken into thin sheets was now widely available and, being lighter with a smooth surface, could be set at a much lower pitch. It was either hidden behind a parapet on terraces which now appeared to be flat-roofed from the street, as distinct from earlier Georgian houses where the roof was still visible, or was hipped and extended over the top of the walls, with noticeable deep eaves. Zinc sheets became available from the 1830s and were used for flatter-roofed areas in preference to the more expensive lead.

FIG 3.18: The Regency version of a garage was the mews, a row of usually two storey buildings along the rear of large terraces and houses in which the owner could keep carriages and horses, with feed storage and staff accommodation on the upper floor. Most of these today have been converted into garages or flats, many self-contained, and are distinctive in their form and position. It was also common for small courts of working-class houses to be squeezed into the rear of town houses as, up until the 19th century, the rich were used to living in close proximity to the poor. These can still be found at the rear of some large urban properties.