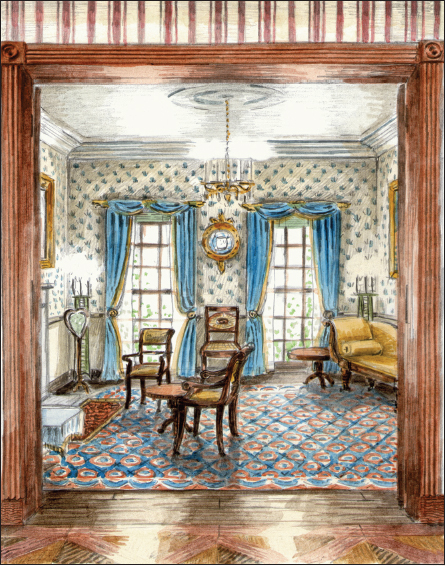

FIG 5.1: A Regency drawing room in which the large sash windows let the outside in.

Within the Regency house, the theme of informality and variety in style which may have only influenced the decorative detail of the façade could be given full rein by ambitious and affluent residents. The number of rooms started to increase and they became more specialised rather than being used for a range of purposes. This meant that furniture like the dining table could now be left in a permanent position rather than being moved back against the wall at the end of meals, although it was not until the Victorian period that this practice became standard. More informal arrangements of furniture, with intimate groupings of chairs and small tables around the drawing room became distinctive of fashionable homes in this period. Principal rooms were opened up to celebrate the newly-found appreciation of nature with bay and French windows allowing in more light. Folding doors between rooms were left open all day and mirrors carefully positioned to reflect the foliage growing outside into the interior.

It was also acceptable to have a different style or mood to suit individual rooms. The interiors did not have to be inspired by one source just because the exterior was in that style. Therefore, you could find a light and refined Neo Classical drawing room next to a sombre Gothick library. This picture was further confused towards the end of the period when eclectic arrangements of furniture and furnishings became fashionable within the same room.

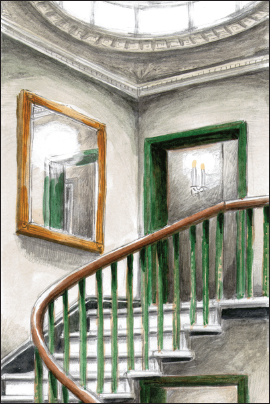

FIG 5.2: Regency staircases were distinguished by thin metal balusters, curving treads floating up walls and skylights adding dramatic illumination in the middle of the house.

These fundamental changes to the interior quickly spread through the fashionable cities and resorts within the tight social groupings of the wealthy but were generally slower to be adopted by those less fortunate or who were living in more remote areas of the country. In the Regency period, however, an awareness of new fashions and an understanding of how to apply them came within the reach of more than just professionals and the very rich. New publications, periodicals and shops now gave the growing middle classes access to this information. Colour coordination and harmonious tones were explained and the concept of interior design put down on paper for the first time. There was also an increase in demand for home-produced goods and materials, partly because of patriotic fervour during the Napoleonic Wars but also as a result of the blockades which limited imports. It became easier for those less well off to emulate these fashionable rooms, as an acceptance of mock materials, growing skills of decorators in graining and marbling, and an increased range of products imitating luxury finishes brought the expensive look within their budget.

The style of the principal rooms could be determined by the use of architectural details, like primitive Greek columns in Neo Classical interiors or pointed arches in Gothick ones. Wallpaper patterns, stencilled designs and a variety of wall hangings could further reflect the historic, exotic or classical theme of a space. Certain finishes or materials could also imply the style, for example, wooden wall panelling in Gothic or Tudor interiors or exposed masonry in medieval-style castles. The work of the Adams brothers from the 1760s and 1770s was still influential during the Regency period. Delicate and shallow Greek revival mouldings, recesses flanked by columns, arched niches along walls and semi-circular ends of rooms (apse) could still be found in the finest interiors. Wooden, plaster and papier mâché mouldings and decoration were more restrained and refined though, compared with earlier Georgian and later Victorian examples.

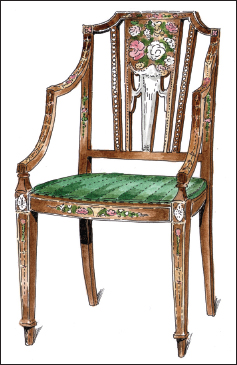

FIG 5.3: Amongst the better-off there was a growing appreciation of interior design and access to fashionable fittings and furnishings. The cabinet maker Thomas Sheraton (his distinctive delicate geometric and painted chair is illustrated here) and amateur designer and connoisseur Thomas Hope both published works which were highly influential. Rudolph Ackermann produced the periodical The Repository of the Arts which promoted a number of new styles, including Gothic, and introduced new ideas on interior design. The work of leading painter and decorator John Crace and his sons Frederick and Henry in the royal properties was also influential in the decorating of Regency interiors.

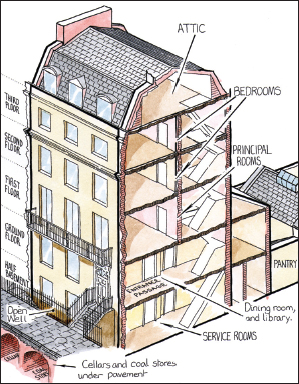

Where the structure of the house was not limited by a narrow plot, it became fashionable for the principal reception rooms to be moved back to the ground floor from the first, where they had been located for most of the 18th century. In more compact villas and terraces, though, the widest rooms were still on the upper floor as the narrow hallway took space away from those on the ground; the exception being the dining room which was often now sited on the latter, while the drawing room above could be opened up into a large space for entertaining. A distinctive feature of Regency interiors was the control of light, not just from large windows and mirrors bringing the outside in but from the use of skylights above stairwells. With more rooms extending over a plot, the middle became more remote from sunlight and so these skylights were especially beneficial.

FIG 5.4: A cutaway view of a large Regency terrace. The ground floor rooms could include a dining room, library and a morning room, while the drawing room was usually still on the wider first floor.

The drawing room had become the principal room in a large house, its name having been shortened from the earlier ‘withdrawing’ room. It was the space where ladies could entertain themselves after a meal and the hosts could display their elegant taste in decoration and furnishings. It was generally regarded as a feminine room and had a light tone although bright, strong colours which were fashionable during the Regency could be used for furnishings and carpets. Its airy feel was emphasised by large, full-height sashes or, by the end of the period, with French windows. These allowed the greenery of trees and garden or sea views to flood in, although at this date these landscapes were usually at the front of the building, with the rear often being a dirty, paved utilitarian place only visited by servants. Ceilings, walls and fireplaces were less ornate than 18th-century drawing rooms, with mouldings flatter and less fussy. Dado rails were still used where chairs were rested up against the wall, while more fashionable interiors could have groupings of furniture in the centre of the room and full-height lengths of printed paper on the wall.

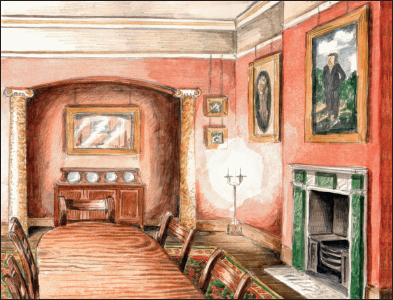

In most houses during the Regency, the dining room was more often than not on the ground floor. With the gentlemen remaining here after the meal to discuss issues of the day, it became very much a male domain. It had strong-coloured walls, often painted red as it was deemed the colour best suited as a background to the gilt-framed pictures of hunting scenes and family portraits which often hung here. The table was beginning to become a fixed piece in the centre rather than being moved to the side after a meal although the dado rail, like in the drawing room, was still used to protect walls from the furniture. The other essential piece in the room was a sideboard, sometimes recessed into an alcove flanked by columns in the finest interiors. It would have been an expensive item, used for serving the meals, although many held a chamber pot for gentlemen to relieve themselves after the ladies had retired to the drawing room.

FIG 5.5: A modestsized drawing room with upholstered sofas and side tables.

FIG 5.6: A large Regency dining room with round ended table and chairs fixed in the middle and an alcove featuring a sideboard at one end. Pompeii red (shown here), darker reds, lighter lilacs and peaches were popular colours.

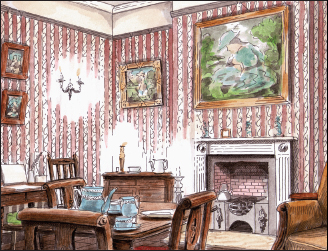

Every self-respecting gentleman would have expected a library or study and if the house was not sufficiently large for one, then space would have been made in the drawing room to house his books, artefacts and art worthy of display. Wooden panelling could be found in Gothic-themed libraries and strong colours to set off the paintings and bookcases (usually with glass-fronted doors) which covered the walls. A desk, chairs and a lectern on which to display a notable manuscript would have also been found.

As these principal rooms became more rigid in their role, so the tasks and entertainment which had formerly taken place within them gained their own specific name, for example, the music room, which was used for small private concerts and instrument practice. The parlour had long been a space for families to hold private discussions (from the French verb parler meaning ‘to speak’) but it was becoming less common during this period. The drawing room had taken over some of its role as the house became more focused on entertaining; and the morning/breakfast room was replacing it as a family space for taking light meals and answering correspondence. Parlours could still be found in smaller housing and rural properties, where it complemented a kitchen cum living room and was much treasured by the lower middle classes as a room reserved for special occasions.

FIG 5.7: A morning room with a lighter and simpler feel than others on the ground and first floors. A small table and chairs were used by the family for breakfast and light meals, whilst a desk on the back wall was used for writing letters.

Out of sight in the basement or the rear of a house, the kitchen, scullery and other service rooms were not intended to be seen by the family or guests and, hence, had little attention paid to them with regard to style and decoration. The kitchen was the hub of the operation, with a central preparation table, a range or open fire (both in the largest houses) and a painted pine dresser; while the adjoining scullery was used for washing crockery, utensils and clothing if there was not a separate laundry. As country gentlemen had begun to take an interest in agriculture, the one service room that was sometimes lavishly fitted out, though, was the dairy.

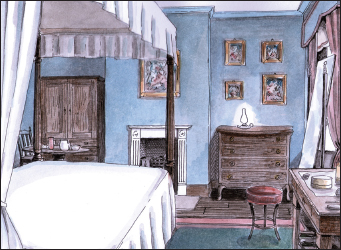

In most houses there would have been a hierarchy of decoration. Whilst the entrance and principal rooms on the ground floor and first floor would have the finest moulded details on the walls and ceilings, the standard of fittings tended to drop as one ascended to the bedrooms. Doors would have flat panels, door furniture be less ornate, cornices could be plain, and walls were often covered with cheaper papers or paint. Bedrooms were simply decorated in light tones, with blue a favourite colour for the walls, whilst white bed linen now became fashionable. Four posters were still common, although half testers with fabric draped over a canopy at one end were growing in popularity. As bathrooms were very rare during this period, washing and dressing took place in the bedroom or an adjoining space. Servants would bring up hot water for the wash basins and the occasional bath, and clean away the chamber pot kept under the bed. During this period, water closets were becoming more common in large houses but they were nearly always sited on the ground floor as water pressure was too weak at this date to allow them to be positioned upstairs.

FIG 5.8: A Regency bedroom, with fashionable white linen and light blue walls.

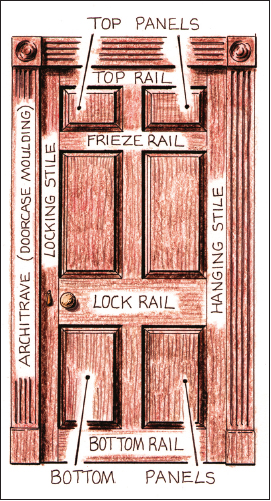

Interior doors were panelled, with six fielded panels being common, whilst those in upper rooms out of the sight of guests might be simpler in form. Polished mahogany or oak doors were desirable but most would have been made from pine which was either stained or grained to look like a hardwood or painted, often with a flat off-white or stone colour. Now it was being mass-produced, brass was becoming popular for interior door furniture which consisted of oval or round knobs, finger-plates and surface mounted locks. Later in the period, these locks were replaced by mortise types in the finest houses.

FIG 5.9: A Regency six-panelled interior door, with a distinctive reeded doorcase moulding with bull’s eyes in the corners.

FIG 5.10: Examples of Regency door knobs (handles were rare in this period).

Walls were usually plastered; with wooden panelling only appearing below the dado rail in some halls and dining rooms or as a more prominent feature in Gothic-themed rooms. The finished surface could be painted with a coloured distemper. Reds seem to have been very popular, with greens in drawing rooms and light blues in bedrooms; other colours like lilac, maroon and stone colours were also used. A strong Wedgwood blue and bright yellows which are distinctive of the period were probably a bit too daring for most tastes and only appeared in the most fashionable interiors. Walls by this period were treated more as a background for fine furniture and artwork rather than as a bold architectural statement in their own right.

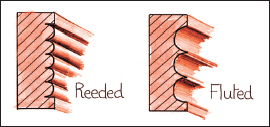

Mouldings were shallow and less busy than in 18th-century interiors and coloured the same as the surrounding wall or picked out in an off-white or stone colour with a touch of gilt. They were made from plaster, wood or papier mâché and could be formed in situ in the finest examples or, more often now, were mass produced for builders and decorators to apply to the walls and ceilings. Reeding was a very distinctive form used throughout the house with round bull’s eyes in the right-angled corners of fittings like door cases. Other architectural features like columns and fireplaces could be made from scagliola, a mix of a coloured plaster with marble chippings, which could be polished to create an authentic finish.

FIG 5.11: Reeded or fluted mouldings were widely used on fireplaces, furniture and plaster work.

FIG 5.12: Example of wallpapers (left pair) and fabrics (right pair) from this period. Although stripes are closely linked with the Regency period, they may not have been as widely used as florals, damasks and small repeating motifs. Colours tend to be brighter and more vivid than in the 18th century, especially after C.R. Cockerell revealed that the Ancient Greek buildings had been painted in strong colours. They also became generally lighter in the 1830s. Pompeii red was a popular colour (see Fig 5.6) discovered in the ruins of the buried Roman city, yet recent work has shown that it was in fact a yellow which had discoloured during the eruption!

Fabrics had long been used as a wall covering and were still hung in grand houses. However, improved domestic production was making wallpaper increasingly popular. These papers tended to copy designs of fabrics, with stripes being particularly distinctive of the period. Other designs included trellis, florals, small repeating motifs and Chinese patterns. Some imitated other materials like marble or fine masonry, while moires and flocks which looked like fabric were also popular. Towards the end of the period, colours generally become lighter and designs which contained small painted images within them like landscapes or battles also became common. Papers at this date were hung or pinned to the wall or a frame rather than glued directly to it and were often varnished. Stencilling also became popular in this period to imitate patterned wall covering.

The ground floor in some of the finest houses could be made from stone flags or marble, especially in the entrance hall, with quarry tiles and brick paviors in service areas. In most other cases, it was formed from softwood floorboards, hand cut, some with individual tongues inserted between them and a coloured or polished finish so they appeared like a finer wood. Sometimes, they were limewashed so they gained a grey tone as they faded. Parquet flooring became popular again. At first it was used just around the border but, by the 1830s, increasingly, it covered the whole floor of the finest rooms. As with other aspects of Regency interiors, imitation was rife. Scagliola was used to make marble-effect borders, boards were stencilled to appear like another material, and plaster and paint applied to create fake stone floorings.

In the finest rooms, the ceiling could be formed into a shallow bow or could have a deep concave cornice (coffered ceiling), with shallow moulding or painted Neo Classical or geometric designs. A painted sky across the ceiling which made it look like there was no roof was also fashionable in some large houses, mainly during the 1820s. In most houses, though, the ceiling was relatively plain, painted a flat off-white, with decoration limited to the cornice.

FIG 5.13: Decorative plasterwork from a Regency house featuring Classical motifs.

FIG 5.14: Examples of plain and patterned iron balusters, with distinctive spiral hardwood handrails.

Staircases in the Regency era were revolutionised by the use of iron. Although fine wooden balusters and treads were fitted in many houses, plain cast-iron sticks supporting a mahogany handrail ending in a spiral at the bottom is distinctive of the period. They were often fitted in conjunction with cantilevered steps which seem to float up the wall; the finest houses having elliptical spaces with glass lanterns above to create dramatic lighting effects. More decorative cast-iron balusters with Greek Revival designs like an anthemion or acanthus leaves were also popular.

The most notable feature within a room and around which it was centred was the fireplace. Coal grates were now standard in urban areas and as these required a smaller space for the coal to burn, they tend to have smaller openings than older wood burning fires. Iron grates with an adjustable width and flattopped blocks to one or both sides (hob grates) were popular, featuring decorative castings on the face to complement the style of the room. Although Count Rumford had made a list of suggested improvements to the design of the fireplace to improve draw and efficiency, his improvements were only gradually implemented. Register grates with an adjustable flap above the fire were only slowly adopted and did not become a standard fitting until the mid 19th century.

The surround could be made from marble in the finest examples or cast iron, timber, scagliola, Coade stone or plaster which was painted or polished to appear like stone. A common design was based upon Palladian types used in the 18th century but stripped of elaborate decoration like figurines. They had a plain panel in the centre and simple pilasters or vertical panels up the sides often in a coloured marble (see Fig 5.16), as plain white surrounds fell from favour. In lesser rooms simple reeded surrounds were popular. In the 1820s and 30s simple Gothic designs with a shallow pointed arched opening became fashionable. The mantel above the fire tends to still be shallow since it was not usually covered with ornaments at this date although old surrounds may have had a deeper one fitted later. A set of tools and fire screens could also be found in rooms; the latter sometimes being distinctive oval shapes supported on a metal stand to protect just the face from the heat.

FIG 5.16: A fireplace surround, comprising white and coloured marble and simple decoration.

The striking simplicity and austerity of many Regency interiors compared to those immediately before and after was also reflected in much of the furniture produced in the period. As with the style of house, there was an increasing range to choose from: Gothic was popular from the 1820s, with Elizabethan by the 1830s, as well as foreign designs like Louis XIV or Chinese influenced pieces. New forms of furniture were also developed during this time. As female dress became lighter and less cumbersome, so day beds and chaise longues became popular for languid relaxation. The sofa table at a height convenient for these was introduced, together with the familiar Windsor chair from the furniture town of High Wycombe. The range of materials increased, with oak and mahogany still desirable. New imports like satinwood and rosewood added variety or were often used to create inlaid patterns while cheaper woods could be painted, domestic marbles were polished up for tops, cane woven for seats, and brass used for knobs and fittings.

FIG 5.17: Round, convex mirrors with distinctive frames, as shown here, were very popular in Regency interiors.

Underlying these new developments were certain characteristic features which help distinguish a Regency style of furniture made popular by Thomas Sheraton and George Smith. Chairs tend to be more geometric than previous examples, with thinner more refined elements and simple, restrained decoration. The sweeping curved sabre leg and animal claw foot were commonly used. Tables with a single or double pedestal rather than legs around the outer edge were popular, usually with circular, octagonal, oval or roundended tops. Chests were made with distinctive bow fronts; glass-fronted cabinets had pleated silk gathered up like small fixed curtains across the inside of the door; thin strips of brass were used to edge or define inlay work; and the lion’s head handle became popular.

FIG 5.18: Examples of Regency furniture: a chaise longue (top left), sofa table (top right), dining chair (bottom left), sideboard with pleated fabric in the glass doors (bottom centre) and a bergère (bottom right) which is a relaxed upholstered chair with caning under the arms.

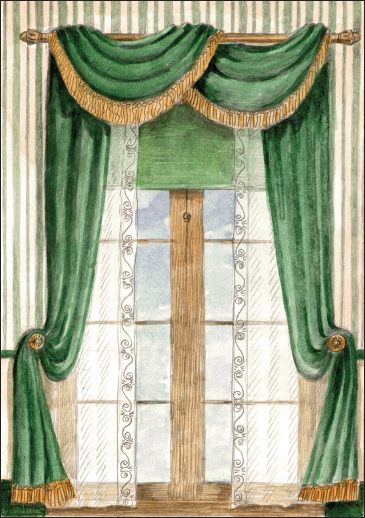

Behind the internal shutters which were commonly built into the sides of sash windows was an increasingly dense battery of fabric designed not only to create privacy within but also to protect precious furniture and coverings from the sun. Roller or slatted wood blinds fitted closest to the window became popular during this period. Some of the former were covered with landscapes to make an attractive scene when drawn down, while the latter were often coloured green. Next in would be a sub curtain of usually white muslin before the main set which could be edged with a border (black was fashionable in the middle of the period) or tassels of gold or silver colour. These curtains could be hung on a brass or wooden rod and drawn in the modern manner or were permanently fixed with the lower part hung on hooks or cloak pins to the side when opened. In principal rooms the rod was sometimes covered by a valance or dressed with draped fabric, with only the decorated finials visible at each end. Occasionally this material could be extended across the ceiling to create tent rooms. In less important rooms the curtains were simpler and lighter in design.

FIG 5.19: Example of a curtain arrangement in a principal room, with muslin sub curtains and a green roller blind behind the main set draped over cloak pins.

With the idea of coordinating colours becoming fashionable in the period, the fabrics used for upholstery and curtains could match or complement each other. The mass production of cheaper, washable cotton which was lighter than many previously popular fabrics was widely used, with glazed or unglazed chintzes becoming a common feature especially in bedrooms. Traditional luxury coverings like silk and leather were still desirable, the latter mainly for dining and library chairs. The range of colours for printed fabrics increased; with deep purple, blue, yellow, red and green being fashionable, either as a plain material or set on a lighter background within a design. Patterns included ones with Greek motifs and architectural features, florals, trellis, damasks and, by the 1820s, stripes which are so distinctive of the period. It was common for the expensive upholstery and woods used on chairs to have loose covers draped over them for protection from sunlight and everyday use, with these only being removed when guests were expected.

A large carpet piece leaving a border of a foot or so around the edge of principal rooms was the most common arrangement although fully fitted versions became popular for a while during this period. The problems with cleaning, however, made it a short-lived fashion. The carpet could also colour coordinate with the curtains and upholstery or earlier in the period have a pattern which matched that of the ceiling. Although oriental carpets were still desirable, domestic production increased such that Axminster (knotted pile) and Kidderminster and Wilton (woven pile) became popular.

As with furniture, it was common for the carpets to be covered to protect them from wear and tear. Despite spending a small fortune on these luxury carpets, most houses had the parts where people walked or ate covered by green or brown druggets, (rugs made of a coarse woollen fabric), and the area in front of the fire fitted with a newly-introduced hearth rug, with these only being removed when guests were expected. In less important rooms, along with druggets, cheaper materials like rush matting and floor cloths were used; this latter solution was a canvas sheet which was covered in layers of size and paint and then decorated with a pattern usually in imitation of a luxury floor covering.

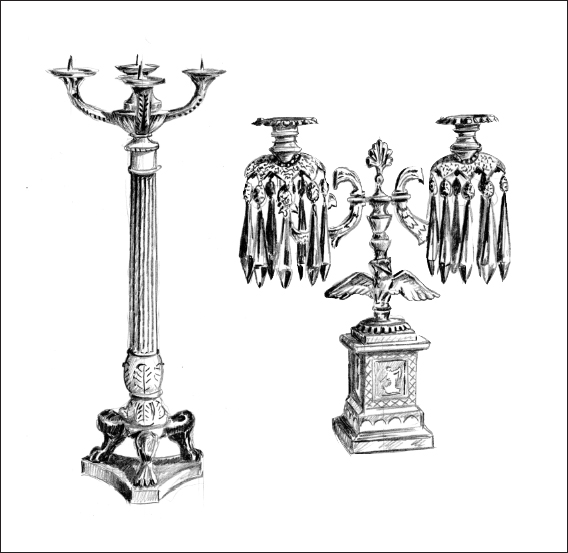

Lighting began to improve in this period although the candle, which had been the main source during the previous century, was still widely used. Oil lamps began to be found in some households, becoming widely popular by the 1820s as their design improved. They had to have the reservoir holding the oil above the wick so that gravity could feed the flame. Despite many solutions to improve the feed, they could look cumbersome and had a reputation for being unreliable. It was not until the 1860s, when thinner paraffin was introduced, that the familiar lamp with the reservoir under the flame was devised.

Gas lighting was the new wonder of the age as at first streets and factories became lit by this much brighter light source. However, it also was very dirty and unreliable. Poor installation resulted in a number of explosions so that although it was installed in the homes of the rich, mainly in London, it did not become universally popular until Victorian improvements and its much publicised installation in the new Houses of Parliament.

FIG 5.20: Examples of a Regency torchiere and a candelabra.