C

Cab A unit of dry measure of capacity or volume, mentioned only in 2 Kings 6:25 (Heb. qab). This unit was a little less than half an omer and equivalent to about two liters. See also Weights and Measures.

Cabbon See Kabbon.

Cabin The KJV translation in Jer. 37:16 of the Hebrew word khanut, referring to a compartment within a dungeon (NIV: “vaulted cell”; NRSV: “cells”).

Cabul See Kabul.

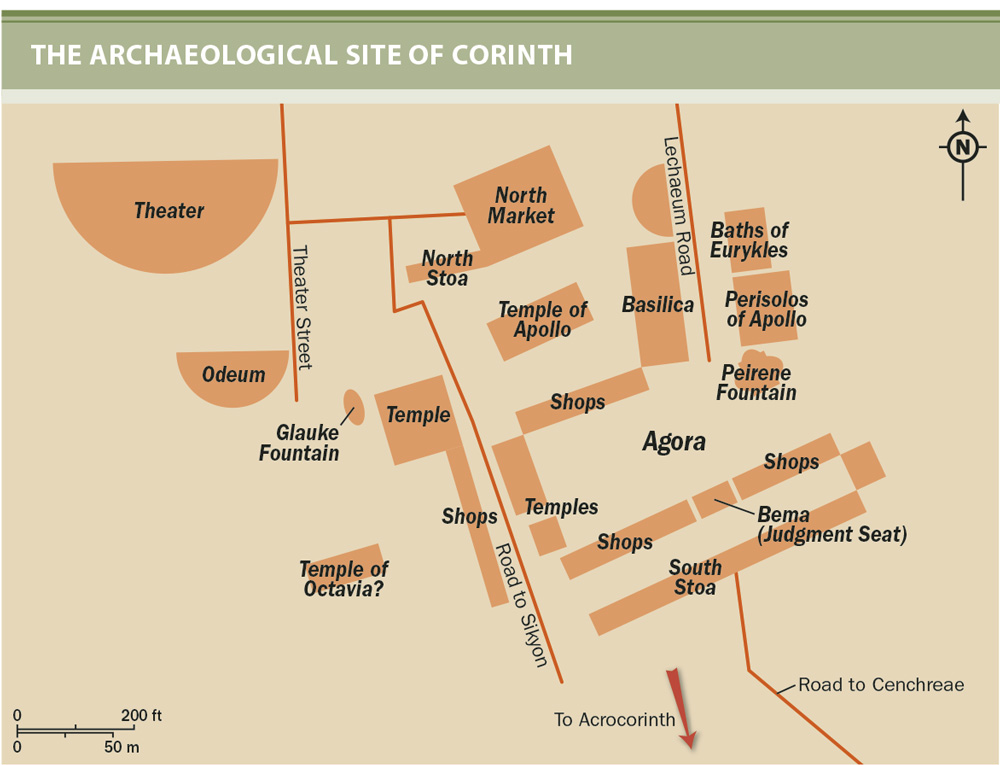

Caesar The family name of the Roman emperors following Julius Caesar (100–44 BC). Emperors after Nero retained the title “Caesar,” although they no longer belonged to the family line. The NT alludes to four Caesars: Augustus, also called “Octavian” (r. 31 BC–AD 14), called for the census (Luke 2:1) that brought Mary and Joseph to Bethlehem prior to Jesus’ birth. Tiberius (r. AD 14–37) is named in Luke 3:1 and was the Caesar ruling when Jesus was questioned about paying taxes to Caesar (Matt. 22:17–21; Luke 20:22–25). The famine predicted by Agabus occurred during the tenure of Claudius (r. AD 41–54) (Acts 11:28), the emperor who prompted Aquila and Priscilla’s relocation to Corinth (Acts 18:2) when he expelled the Jewish population from Rome (AD 49). Nero (r. AD 54–68) was the Caesar to whom Paul appealed (Acts 25:10) and from whose household Paul sent greetings to the Philippians (Phil. 4:22).

Caesarea Built by Herod the Great between 22 and 10/9 BC and named in honor of Caesar Augustus, Caesarea was a major international seaport located on the Mediterranean coast about fifty-five miles northwest of Jerusalem. Also known as Caesarea Maritima or Caesarea Palestinae, it was built on the site of an earlier Phoenician trading station and town known as Strato’s Tower. The ancient historian Josephus describes Herod’s ambitious building program for the city (J.W. 1.408–15; Ant. 15.331–41), which included palaces, an amphitheater, a theater, a temple dedicated to Caesar, a marketplace, and a great harbor complex called “Sebastos.” The immense harbor complex reflected Herod’s great plans for the city, particularly in regard to its maritime role, and Caesarea did achieve international prominence.

After Herod’s death in 4 BC, his eldest son, Archelaus, succeeded him as king. Augustus removed Archelaus from power in AD 6, and his kingdom, including Caesarea, was absorbed into the Roman Empire. The city was then made the seat of Roman government in the province of Judea. Pontius Pilate governed Judea from Caesarea when he presided over Jesus’ trial.

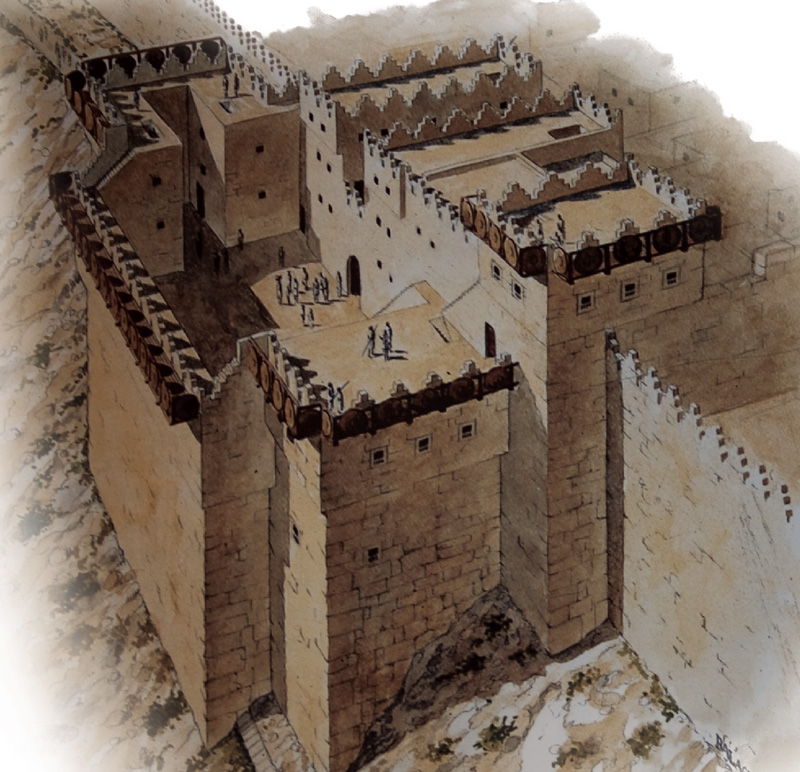

Caesarea of Herod the Great (first century AD)

Caesarea figures prominently in the establishment of Christianity, according to the book of Acts. Philip, a deacon in the Jerusalem church, appears to have brought Christianity to the city (8:4–40). At the beginning of Paul’s ministry, threats from the Jews in Damascus forced Paul to flee to Caesarea and from there to Tarsus (9:30). Caesarea is where the centurion Cornelius and his household became the first Gentile converts, and where Peter received God’s revelation regarding the acceptance of Gentiles into the kingdom of God (10:1–48).

Caesarea appears to have been an urban center for the early Christian movement. Paul came to the city at the end of his second and third missionary journeys (Acts 18:22; 21:8). On his way to Jerusalem, Paul stayed with Philip, who lived in Caesarea along with his four prophesying daughters (8:40; 21:8–9). It was in Caesarea that Paul made his decision to go to Jerusalem, despite Agabus’s prophecy that the Jews would deliver him over to the Gentiles and the urging of Paul’s companions and the local people for him not to go (21:10–13). Following Paul’s arrest in Jerusalem, he was sent to Caesarea to appear before the governor Felix and remained imprisoned there for two years. When Felix was succeeded by Festus, Paul appealed to Caesar and was sent to Rome (25:11).

Caesarea Philippi A city located about twenty-five miles north of the Sea of Galilee at the southwest base of Mount Hermon (present-day Jebel esh-Sheikh). Caesarea Philippi was located where the modern city Banias sits, on the northwestern tip of the Golan Heights, about three miles south of Lebanon.

Archaeologists are certain where Caesarea Philippi stood because the location of the cave that gave the town both its ancient and modern names (“Paneus,” in honor of the Greek nature deity Pan) has been known since antiquity. There is no known archaeological evidence for settlement of the town prior to the Hellenistic era. Caesarea Philippi was originally the site of a sanctuary dedicated to the worship of Pan. Prior to Herod the Great’s reign, the area was sparsely populated.

Sacred pagan sanctuary area at Caesarea Philippi

In 20 BC the Roman emperor Octavian (r. 31 BC–AD 14) gave the area around Caesarea Philippi to Herod the Great, who made the town his capital. Herod’s son Philip took control after his father’s death, rebuilding the city as Caesarea in honor of Octavian’s son Tiberius Caesar (in approximately 1 or 2 BC). During Philip’s reign it was commonly called “Caesarea Philippi” (4 BC–AD 34) to avoid confusion, since other cities in the Roman Empire at that time were also called “Caesarea” (such as Caesarea Maritima).

Another of Herod the Great’s sons, Agrippa I, ruled Caesarea Philippi for three years (AD 41–44), after which time it reverted to Roman rule until AD 53, when Agrippa II (the son of Agrippa I) was given control of the city (ruling for forty years, until AD 93). Agrippa II built a fortress there and renamed the city “Neronias” (after the emperor Nero), but this name did not become popular and quickly fell into disuse after Nero’s reign ended.

The Roman emperor Titus stopped in Caesarea Philippi to rest his army after subduing the Jewish insurrection of AD 66–70. While there, Titus killed many captured Jews in public gladiatorial spectacles. The name of the town reverted back to the older name “Caesarea Paneas” in the second and third centuries AD and then simply to “Paneas” from the fourth century AD onward.

The towns Baal Gad (Josh. 11:17; 12:7; 13:5) and Baal Hermon (Judg. 3:3; 1 Chron. 5:23) were located in the region of what would become Caesarea Philippi. During Jesus’ ministry, the town was populated mostly by Gentiles. The two explicit mentions of Caesarea Philippi in the Bible occur in parallel accounts in the Gospels: it was in the region of Caesarea Philippi that Peter made the memorable confession that Jesus is Israel’s Messiah (Matt. 16:13–30; Mark 8:27–30; see also Luke 9:18–22).

Caesarea Philippi experienced significant expansion and numerous large-scale building projects throughout the reigns of Herod’s descendants, but it dwindled dramatically in size in the following centuries, eventually becoming a small village. During medieval times, the city was refortified as a Crusader outpost.

Caesar’s Household Members of the Roman imperial palace staff who carried out the various logistical duties necessary to facilitate the emperor’s rule over the empire. Such persons often were wealthy and influential beneficiaries of imperial favor, but large numbers of slaves were among their number as well. Inscriptions exist naming members of “Caesar’s household,” including many of the same names that appear in Rom. 16. Paul closes his letter to the Philippians with greetings from himself and “Caesar’s household,” thus indicating Rome as the probable origin of that letter (Phil. 4:22).

Caiaphas High priest from AD 18 to 36/37. He is best known for presiding over the Jewish trial of Jesus. The Bible mentions him explicitly in Matt. 26:3, 57; Luke 3:2; John 11:49; 18:13, 24, 28; Acts 4:6. Gratus, a Roman prefect of Judea, appointed Caiaphas to the office, and Vitellius, a Roman legate of Syria, removed him from it. According to John 11:49–52, he prophesied about Jesus’ death. He appears several times in the writings of Josephus, though conspicuously rarely considering the length of his tenure.

Cain The first son of Adam and Eve, initially assigned Adam’s task of working the land. His story is told in Gen. 4: After God favors his younger brother Abel’s offering over his own, he becomes jealous, angry, and downcast (vv. 1–5). God offers him the hope of righteousness and caution against sin, but Cain murders his brother (vv. 7–8). Similar to his parents’ reaction when confronted by God, Cain lies and pleads ignorance when God confronts him about Abel’s death (v. 9), then receives a change in vocational assignment and is banished from God’s presence (v. 14). He becomes a wanderer, and his lineage is prone to arrogance and deceit. The NT use of his name is related to selfishness and wickedness (Heb. 11:4; 1 John 3:12; Jude 11).

Cainan Greek kainam for the Hebrew qenan, the name for two different persons in Jesus’ genealogy according to Luke. (1) A great-grandson of Adam, a son of Enosh, and the father of Mahalalel (Luke 3:37 [NIV, NET: “Kenan”]; cf. Gen. 5:9–14; 1 Chron. 1:1–2). (2) A great-grandson of Noah, a son of Arphaxad, and the father of Shelah (Luke 3:36; cf. Gen. 10:24; 11:12–13 LXX). Since this Cainan does not appear in the MT genealogies, Luke apparently used the LXX for this section of his genealogy for Jesus. It must be remembered that omission of names was an acceptable practice in ancient genealogies for various purposes (e.g., the mnemonic device of Matt. 1:17) so that “son of” can mean “descendant of,” and “father of” can mean “ancestor of.” See also Kenan.

Cake Various kinds of bread and cakes suitable for offerings appear in Lev. 2. A kind of crisp cake, “cracknel” (KJV), is mentioned in 1 Kings 14:3. Thin cakes were offered in idolatrous worship to the Queen of Heaven (Jer. 7:18; 44:19).

Calah An Assyrian city built by Nimrod after establishing his kingdom (Gen. 10:11–12). The city is known as one of the four most important Assyrian cities, though it is specifically mentioned only in this one place in the Bible. The city, in modern times known as Nimrud, was situated on the Tigris River, about twenty miles south of Nineveh. Calah only became significant in Assyria during the reign of Ashurnasirpal II (c. 884–859 BC), who made it his capital. His palace included some of the most important reliefs and discoveries ever uncovered concerning Assyria’s history.

Calamus A word in the OT (Heb. qaneh) that sometimes designates a specific scented reed, and sometimes the commercial product made out of that reed. Probably imported from India, calamus was used for its aroma and as a tonic and stimulant (Isa. 43:24; Jer. 6:20; Ezek. 27:19). The aromatic product was an element of various perfumes (Song 4:14) and was used as incense for tabernacle worship (cf. Exod. 30:23). Also known as sweet flag (Acorus calamus), it has some carcinogenic properties and hallucinogenic effects at high doses and in modern times has been banned as a food additive in the United States.

Calcol See Kalkol.

Caldron A cooking vessel, named in 1 Sam. 2:14 as one of the vessels from which Eli’s sons took boiling meat. The Hebrew word here, qallakhat, is rendered elsewhere as “kettle” or “pot” by some modern versions (Mic. 3:3). The KJV renders the Hebrew sir, also a cooking vessel, as “caldron” (Ezek. 11:3, 7, 11).

Caleb (1) One of the twelve spies sent into the promised land by Moses (Num. 13:1–14:45). He represented the tribe of Judah. When the spies returned, they reported that the land was beautiful and fertile, flowing with “milk and honey.” However, they also described the inhabitants as fearsome and dangerous. The majority of the spies gave a counsel of despair, saying, “We can’t attack those people; they are stronger than we are” (Num. 13:31). Caleb, supported by Joshua of Ephraim, gave a minority report, advising that they attack the land. The advice of the ten spies convinced the people who lacked faith in God’s ability to give them victory. In response to their complaints, God determined that the generation of Israelites who came out of Egypt would die in the wilderness. Thus, they spent forty years wandering before they were permitted to enter the land. The faithful spies, Caleb and Joshua, were exceptions, the only ones in their generation allowed to actually enter the promised land.

Caleb was forty when he served as a spy and eighty-five at the time the land began to be distributed to the tribes. Caleb came forward and asked that Joshua give him the land around Hebron. To actually possess the city, he successfully drove out the dreaded Anakites, who particularly put terror in the hearts of the Israelites (Josh. 14:6–15; 15:13–15).

(2) A descendant of Judah through Perez and Hezron (1 Chron. 2:9, 18–20).

Caleb Ephrathah A place mentioned only in 1 Chron. 2:24 as the location where Hezron, the father of Caleb, died. Some have suggested that Caleb Ephrathah may have been the place where Caleb and his wife Ephrath (1 Chron. 2:19) lived, possibly Bethlehem (see Mic. 5:2). Others, however, preferring the LXX reading, see Eprathah as a woman: “After the death of Hezron, Caleb went in to Ephrathah” (cf. ESV, NET).

Calendar Because calendars are culturally constructed systems, there are several important differences between the modern calendar and the calendars used in biblical times. When dealing with ancient Jewish and early Christian sources, we can reconstruct complete calendar systems. However, the Bible itself, written over many centuries, employs several calendar systems and systems of dating. No single normative calendar system emerges from biblical materials. Nevertheless, many aspects of life in biblical Israel depended on the use of calendars, which regulated religious festivals, agricultural activity, various aspects of the legal system, and the recording of historical events.

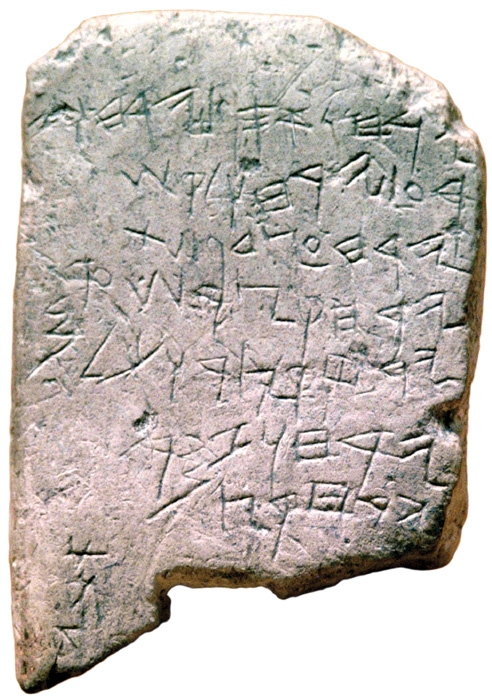

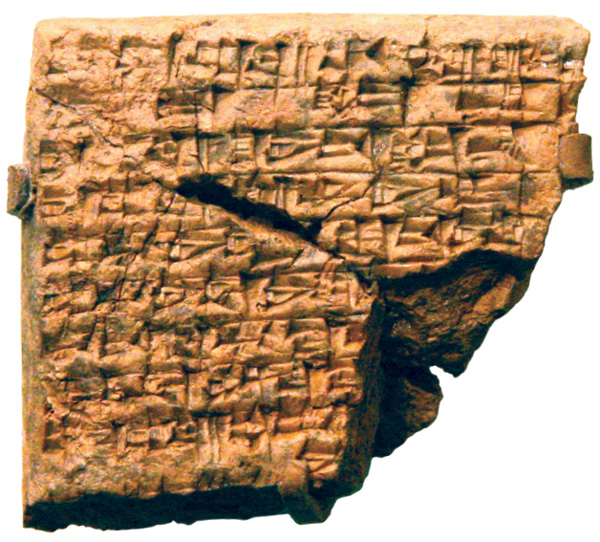

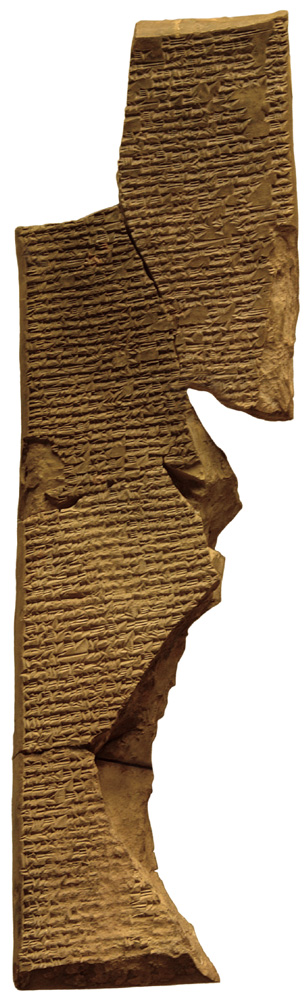

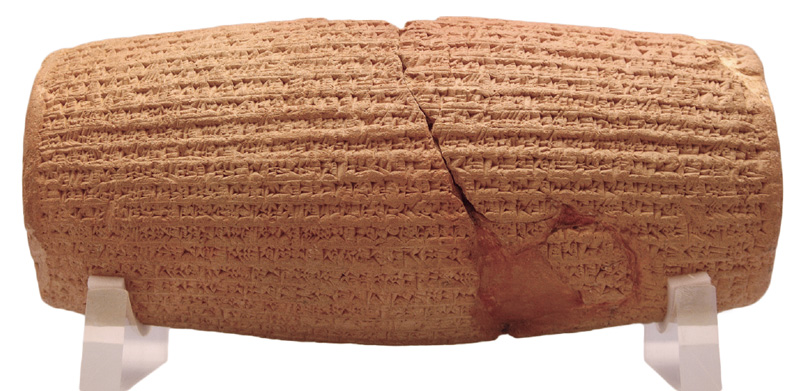

The Gezer Calendar

MEASUREMENT OF TIME IN ANTIQUITY

There were several methods of reckoning time in antiquity. Some units of time corresponded to the observation of celestial phenomena (see Gen. 1:14), such as the rising and setting of the sun (defining the day), the waxing and waning of the moon (the lunar month), the ascension of the sun in the sky at noon (the solar year). Other measurements of time were defined by the agricultural cycle, including planting and the beginning and end of the harvest (see Exod. 23:16; Ruth 1:22). An agricultural scheme serves as the basis of the Gezer Calendar, an important archaeological object of the tenth century BC unearthed about thirty miles northwest of Jerusalem. The Gezer Calendar divides the year into eight periods of one or two months, each of which corresponds to the planting, tending, and harvest of various crops. Still other units of time, such as the seven-day week and the lunisolar year (see below), were derived by counting or calculation and did not correspond to any observable celestial or terrestrial phenomena.

The division of days into hours and minutes is possible in modern times because of mechanical and electronic timepieces. Without these devices, divisions of time shorter than the day would have been approximations at best. Biblical texts refer to dawn, morning, noon, evening, night, and midnight. In NT times, the twelve daylight hours were numbered (Matt. 27:45; John 11:9). There was also a system of dividing the night into “watches,” attested in both the NT and the OT.

THE MONTH AND THE YEAR IN THE BIBLE

The Hebrew words for “month” are related to the words for “moon” and “new” (i.e., the “new moon”), which suggests that the ancient Israelite month was a lunar month corresponding to the waxing and waning of the moon over a period of twenty-nine or thirty days. The Bible refers to numbered days in each month, as high as the twenty-seventh day.

There are several systems of naming the months in the Bible. Four “Canaanite” month names appear in the OT: Aviv (the first month), Ziv (the second), Ethanim (the seventh), and Bul (the eighth). Because of the infrequent use of these names, some scholars have questioned whether this system was in widespread use in ancient Israel. The names probably are derived from agricultural terms.

In many cases the months are simply numbered. In this system, the first month began in the spring season. According to biblical narrative, this way of reckoning the beginning of the year was commanded to Moses at the time of the exodus (Exod. 12:1). However, the Bible applies this scheme to events much earlier, as in the story of the flood of Noah, which began in the second month (Gen. 7:11), and scholars have associated the numerical system of months with late biblical sources, around the time of the exile. The system may have come into use around that time and replaced an older system.

In some late biblical texts Babylonian month names are adopted, including Nisan (the first month), Sivan (the third), Elul (the sixth), Chislev (the ninth), Tebet (the tenth), Shebat (the eleventh), and Adar (the twelfth). Following biblical usage, the Babylonian month names were adopted in the ancient Jewish calendar, which is still in use today.

Based on references to the “twelfth month,” the Israelite year apparently consisted of twelve lunar months. Accordingly, the lunar year consisted of approximately 354 days, which means that it would not have corresponded to the solar year of approximately 365¼ days. The beginning of the year would have drifted between eleven and twelve days each year. Presumably, this would have been an unacceptable situation, given the fact that many of the biblical festivals were both assigned to lunar dates and were correlated to agricultural events. The problem probably was solved through the intercalation of “leap months,” as was the practice in maintaining the later Jewish calendar. The result is a lunisolar calendar, in which the year is composed of twelve lunar months and is corrected relative to the solar year by the periodic addition of a second Adar (Adar II) seven times in every nineteen-year period. The Bible does not mention this procedure or identify who was responsible for maintaining the calendar in ancient Israel.

BIBLICAL DATES

Modern systems of absolute dating, in which all years are numbered relative to a single historical reference point—for example, the birth of Jesus (Anno Domini), the journey of Muhammad in AD 622 (Anno Hegira 1) from Mecca to Medina in Islamic culture, and the creation of the world (Anno Mundi) in Jewish tradition—were unparalleled in biblical times. Instead, events were usually dated relative to the reigns of kings, Israelite or otherwise. For example, the accession of Abijah is dated to the eighteenth year of Jeroboam’s reign (1 Kings 15:1), and the proclamation of Cyrus is dated to his first regnal year (Ezra 1:1). In other cases, events were dated relative to important historical events. The beginning of Amos’s career as prophet is dated to “two years before the earthquake” (Amos 1:1), and Exod. 12:41 dates the departure from Egypt to the 430th year of the captivity. In other instances, the fixed points on which relative dates are based cannot be determined. The beginning of Ezekiel’s career as a prophet is dated to the otherwise unspecified “thirtieth year” (Ezek. 1:1). The verse may simply refer to Ezekiel’s age.

The same practices of dating events are followed in the NT. The birth of John the Baptist is dated to “the time of Herod king of Judea” (Luke 1:5). The census of Caesar Augustus is identified as “the first census that took place while Quirinius was governor of Syria” (Luke 2:2). As in the OT, such formulas presuppose that the reader has a basic awareness of the succession and reigns of kings and emperors—an advantage lost to modern interpreters, who continue to debate the absolute dating of these events. Perhaps analogously to Ezek. 1:1, the beginning of Jesus’ ministry is dated to his thirtieth year of age (Luke 3:23). Other events and persons reported in the NT can be correlated to extrabiblical historical records to establish absolute dates for biblical events (e.g., the death of Herod Agrippa I in AD 44 [Acts 12:23]). These are distinct from instances in which biblical authors are making a conscious effort to provide dates intelligible to their readers. In contrast to OT historical narrative, for the most part, the NT shows little interest in dating events in its narrative, even according to ancient conventions of relative dating.

Calf Although the calf was not a principal animal used in the sacrificial system, there were significant occasions when a male calf or a heifer was slaughtered. These included the ordination offerings (Lev. 9:2–8) and the ritual for dealing with an unsolved murder (Deut. 21:3–8). A heifer was among the animals that Abram cut in pieces when God made the covenant (Gen. 15:9–18; cf. Jer. 34:18–19). As David brought the ark of the covenant to Jerusalem, a bull and a fattened calf were sacrificed (2 Sam. 6:13). Finally, when the prodigal son returned, the father slaughtered a fattened calf (Luke 15:23). Almost half of the thirty-six occurrences of “calf” refer to an idol.

Calf, Golden See Golden Calf.

Caligula See Rome, Roman Empire.

Calkers, Calking See Caulkers, Caulking.

Call, Calling A call or calling is God’s summons to live one’s life in accordance with his purposes. At creation God instructed Adam to fill the earth and subdue it, and to have dominion over it. God created Eve to be Adam’s lifelong companion and to help him fulfill this task (Gen. 1:28). Thus, in the broader (universal) sense, the notion of calling includes the ordinances that God established at creation: work (Gen. 2:15), marriage (2:18, 24), building a family (1:28), and Sabbath rest (2:2–3).

When Adam and Eve disobeyed God, they became alienated from God (Gen. 3:6–19). Their fall brought the same plight of alienation from God upon all humanity. However, it did not abolish the human duty to carry out God’s original creation ordinances. Since God showers his blessings on everyone alike (common grace), all human beings possess gifts and are given opportunities to “fill” the earth and “subdue” it. Thus, everyone participates in the universal call (Acts 17:25–26). This has come to be called the “cultural mandate.”

However, God’s original intention was to have communion with human beings. This could not be realized unless he made provision for human beings to be reconciled with him. Against this backdrop, God initiated his plan to redeem people from their plight of spiritual alienation.

The general call. The promise of God to bring deliverance through a future descendant of Eve established the provision for individuals (e.g., Adam, Abel, Seth, Noah) to be “called” back into a relationship of favor with him (Gen. 3:15). The first occasion when this call is made explicit is in God’s call to Abram to leave his country and go to a land that God would show him (11:32–12:1). God promised that Abram would become the father of a nation (12:2–3). In response to God’s call and his promise, Abram believed God, and it was credited to him as righteousness (15:6). Abram’s call was implicitly twofold. First, it was a general call to acknowledge this God as the true God and yield to his lordship. Second, it entailed a specific call to leave his country and journey toward a new country.

Several generations later, God appointed Moses to lead these descendants of Abraham out of Egypt, where they had lived for four hundred years. God’s act of delivering them from slavery in Egypt also symbolized redemption from sin’s bondage (Exod. 20:2). God had called the people by means of a covenant to be his own special people, to serve him as a kingdom of priests and a holy nation (19:5–6). This was a call to set their lives apart for God by living according to his commands. This general call was more than a verbal summons; it was also the means God used to bring his people into existence (Hos. 11:1).

The NT indicates there is a general call to all people to believe in Christ (Matt. 11:28; Acts 17:30) that becomes effective in the ones that God has already chosen (Matt. 22:14; Acts 13:48; Eph. 1:4–5). The latter, which theologians identify as the “effectual call,” is what Paul refers to when he says, “Those God foreknew he also predestined to be conformed to the image of his Son. . . . And those he predestined, he also called; those he called, he also justified; those he justified, he also glorified” (Rom. 8:29–30). Thus, this is also a sovereign call.

Particular callings. God has endowed each individual Christian with a particular gift set and calls each one to use those gifts in a variety of ways in service to him (1 Pet. 4:10). These callings include one’s occupation, place of residence, status as married or single, involvement in public life, and service in the local church. In the OT, God gifted Bezalel and “filled him with the Spirit of God, with wisdom, with understanding, with knowledge and with all kinds of skills” (Exod. 35:31–32) to beautify the tabernacle. In the parable of the talents, Jesus teaches that God has made each of us stewards of whatever he has entrusted to us; we are to become skilled in the use of our gifts and to seek opportunities to use them in service to him (Matt. 25:14–30). Desire is an important factor in discerning one’s particular callings (Ps. 37:4). One’s particular calling is progressive, unfolding through the different seasons of one’s life (Eph. 2:10; 1 Cor. 7:20, 24). No particular calling is more “sacred” than another in God’s eyes.

Calneh, Calno See Kalneh, Kalno.

Calvary The name given to the site of Jesus’ crucifixion. In the Greek NT the site is called “Golgotha,” from the Aramaic term meaning “skull,” which is translated in the Gospels as the “place of the skull.” The Latin Vulgate then translates this phrase as Calvariae locum (Matt. 27:33; Mark 15:22; Luke 23:33; John 19:17–18), from which the English term “Calvary” derives. Golgotha could have been given its name because an outcropping of rock gave the place the appearance of a skull, but it seems more likely that Golgotha was a place habitually used for executions. It is clear then how Golgotha warranted its morbid name. The Bible specifies that Golgotha was outside Jerusalem, but not far from the city boundaries of Jesus’ day (John 19:20; Heb. 13:12). Today, Calvary lies within Jerusalem’s Old City, as Herod Agrippa I (r. AD 40–44) changed the boundaries of the city walls. The land eventually held a pagan temple, the Capitolium, which was torn down by the Christian emperor Constantine starting in AD 325 and replaced with a building complex meant to honor the holy site. After the crucifixion, Jesus was laid in a tomb in a nearby garden at the request of Joseph of Arimathea (Matt. 27:59–60; John 19:41). Very early Christian tradition claims to have identified this site, which today is inside the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. All the constructions and renovations of the site have changed Golgotha greatly since the first century, so that it bears little resemblance to a garden or an execution ground. The word “Calvary” has become a shorthand for the death of Jesus in Christian worship, so that sinners are called to come “to Calvary” and receive forgiveness. See also Golgotha.

Calves, Golden See Golden Calf.

Calves of the Lips This phrase appears in the KJV at Hos. 14:2. Since calves were offered as sacrifices to God in the OT sacrificial system, the idea is that those who offer the “calves” of their lips are speaking a sacrifice of praise to God. The NIV and NRSV follow an alternate reading from the LXX, “fruit of our lips,” while the NET maintains the sense of the Hebrew text by rendering it as “we may offer the praise of our lips as sacrificial bulls.” See also Heb. 13:15.

Camel A large four-footed mammal that has been used by humans as a pack animal and for transportation since at least the second millennium BC. The camel found its greatest use in caravans, groups of traders that crossed deserts with goods in order to sell them in foreign markets.

There are two kinds of camel, the dromedary (one-humped) camel that was native to the region of Israel, and the Bactrian (two-humped) camel that is indigenous to central and eastern Asia. Called the “ships of the desert,” they are ideally suited to life in a hot and arid environment. Camels can close off their nostrils and will do so in a sandstorm. Their long eyelashes are able to protect their eyes from the sun and sand particles.

Perhaps camels’ most valuable adaptation is their biological ability to conserve the use of water. In addition to many other water-saving traits, their skin and coats of hair are optimized to reduce the need for sweating, the water content of their waste is well below other animals, and they can retain the amount of plasma in their blood for a remarkable length of time when deprived of water. Camels’ humps do not hold water, as is commonly misunderstood, but are made up of a fatty tissue that constitutes the major energy reserve of the animal.

Camels first appear in the Bible in Genesis in the patriarchal narratives, where they are a part of the pastoral assets (12:16). They are also featured prominently in the story of finding Rebekah to be Isaac’s wife (24:10–36). Joseph was taken to Egypt by a caravan, which carried balm and myrrh in addition to human cargo (37:25). In the dietary regulations of Mosaic law, the camel is unclean and cannot be eaten (Lev. 11:4; Deut. 14:7). Camels continue to appear as beasts of burden and as livestock throughout the Bible in a number of contexts.

Camel’s Hair The thick coat of hair from a camel shed every spring, often used for weaving into a rough cloth. The camel was considered unclean to eat (Lev. 11:4; Deut. 14:7), but apparently not to wear. John the Baptist and earlier prophets wore camel’s hair (2 Kings 1:8; Zech. 13:4; Matt. 3:4; Mark 1:6). The clothing also distinguishes the Baptist from the Essenes, who wore only linen (Josephus, J.W. 2.123).

Camp, Encampment Temporary homes for seminomadic peoples as well as military personnel. A number of Hebrew words are translated in the English Bible as “camp” or “encampment.”

For example, a tirah was a camp protected by a stone barrier or wall (Gen. 25:16; Num. 31:10; Ezek. 25:4), a ma’gal was a ring of wagons or a circular camp (1 Sam. 17:20; 26:5, 7), and a nawah was perhaps a nomadic pasturage camp (Ps. 68:12 NIV).

Remains of the Roman encampment at Masada

The most frequent word for “camp,” makhaneh, occurs over two hundred times in the OT and is derived from the verbal root khanah, meaning “to set up a camp or encampment.” Isaac and Jacob camped during their journeys (Gen. 26:17; 31:25). After leaving Laban and meeting the angel of God, Jacob declared the place of the theophany to be “the camp of God” and named it “Mahanaim,” meaning “double camp” (32:1–2). In Gen. 32:21 Jacob’s camp is probably a traveling entourage composed of a number of tents.

In many cases makhaneh refers to a military camp. After the exodus and during the wilderness journeys, the Israelites resided in this type of settlement (Exod. 14:2, 9; Num. 33; Deut. 2:14–15). Moses led the Israelites out of the camp to meet with God at Sinai (Exod. 19:16–17).

Each tribe had its own camp (Num. 2). Because of the presence of God in its midst, Israel’s camp was to be holy. Leviticus and Deuteronomy contain laws regulating camp life (Lev. 14:3, 8; Deut. 23:10–11). Any unclean person or thing was to be put outside the encampment (Num. 5:1–4; Deut. 23:14). The angel of the Lord encamped around them (Ps. 34:7). The Israelite army encamped at numerous places during the conquest of Canaan (Josh. 4:19) and the monarchical period (1 Sam. 29:1).

The NT uses the Greek term parembolē to refer to the Israelite camp where animals sacrificed as sin offerings were “burned outside the camp” (Heb. 13:11–13). Since Jesus suffered outside the gate as a sacrifice for us, believers are called to join him outside the camp, “bearing the disgrace he bore.” Revelation 20:9 speaks of “the camp of God’s people.”

Camphire The KJV rendering of the Hebrew word koper in Song 1:14; 4:13. Most modern versions translate it as “henna,” a shrub known in Palestine and Egypt.

Cana A village of uncertain location near Nazareth, though Khirbet Qana is a possible candidate. Cana is mentioned only in John’s Gospel. Though undistinguished (its name is always qualified as “Cana in Galilee”), it is given prominence as the place where Jesus performed his first and second signs (John 2:1, 11; 4:46). Nathanael, its only known citizen (John 21:2), raises its status further by becoming the first to confess Jesus as the Son of God and King of Israel (John 1:49).

Canaan Son of Ham, grandson of Noah, and the father of the families that would become known as the Canaanites (Gen. 10:6, 15–19). Oddly, in the account of Ham’s great sin against Noah (seeing his father’s nakedness), Noah cursed his grandson Canaan rather than his son Ham (Gen. 9:18–27). The explanations of such cursing vary, but the passage ultimately establishes the context by which the Bible explains the relationship of the Canaanites to the Israelites in the centuries that followed. The most plausible reasons for why Canaan was cursed rather than Ham center on the irrevocability of God’s blessing of Ham in Gen. 9:1 or that Canaan played some undescribed role in the sinful act. The curse also included a promise of animosity between Canaan and the sons of Japheth (9:27). This element of the curse probably found fulfillment with the entrance of the Philistines (Sea Peoples) into the land at about the same time Israel was entering it under Joshua’s leadership.

Canaan, Land of A region generally identified with the landmass between ancient Syria and Egypt, including parts of the Sinai Peninsula, Palestine from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean, and southern Phoenicia (modern Lebanon). Although there is some discussion about the origin of the name “Canaan” and its meaning, the name apparently arises from the primary inhabitants of the region prior to Joshua’s incursion into the land, since it is primarily used in connection with the phrase “the land of,” indicating that the descendants of Canaan possess it. Because the identity of the land of Canaan was linked as much to its inhabitants as it was to any sort of fixed borders, the boundaries are identified in various ways throughout the biblical text. Such descriptions vary from a rather limited area of influence (as suggested by Num. 13:29) to a larger land spanning an area from the Euphrates to the Nile (Gen. 15:18; Exod. 23:23). Because of its strategic position as a buffer between Egypt and Mesopotamia and between Arabia and the sea, it served as a primary trading outpost and the location of numerous important historical events both prior to and after Israel’s appearance in the land.

In the Bible, the geographical reference “the land of Canaan” finds primary expression, not surprisingly, in Genesis through Judges. The promise to Abraham that his descendants would inherit the land of the Canaanites (Gen. 15:18–21) is the theological focal point of the uses of the term “Canaan” throughout these biblical books. Once that inheritance was achieved and Israel became a viable state, the term’s use seems to serve the double purpose of being both a geographical marker and a reminder of the nature of its former predominant inhabitants. The prophets drew upon the term to remind Israel of the land’s former status, both in its positive (Isa. 19:18) and negative (Isa. 23:11; Zeph. 2:5) connotations. The term is transliterated twice in the NT in the recounting of OT history (Acts 7:11; 13:19). One further connection between Canaan and the perspectives communicated concerning it in the OT is the apparent association of the land with corrupt trade practices. That is, while some believe that the word “Canaan” always meant “merchant” or some similar word, its use in Scripture suggests that the tradesmen of Canaan were of such disrepute in the recollection of ancient Israel that the term became a synonym for “unjust trader” (Job 41:6; Ezek. 16:29; 17:4; Zeph. 1:11; Zech. 14:21).

HISTORY

The proximity of Canaan to Egypt meant that from its earliest periods it found itself beholden to the pharaohs of Egypt. The Egyptian Execration texts from the Old Kingdom era tell of Egypt’s influence over Canaan in the early second millennium. After the expulsion of the Hyksos from Egypt, the pharaohs of the New Kingdom asserted their control over the land. Most famous among these records is Thutmose III’s account of his defeat of Megiddo through the implementation of both cunning and skill. This same pharaoh would establish a system of dividing Canaan and its inhabitants for taxation and administration that would be so successful that Solomon would reimplement the same system during his reign (1 Kings 4:7–19). Even in the weaker days of Egypt following the New Kingdom, pharaohs such as Necho and Shishak and their successors the Ptolemies would often seek to revisit the days of glory in campaigns into Canaan.

In addition to Egypt, other outside forces found their way into Canaan and exerted influence on its development. The earliest settlers seem to have come from Mesopotamia, and Semitic influence is witnessed as early as 3000 BC. In the period between Egypt’s control of Canaan during the Old Kingdom and its later reassertion after expelling the Hyksos, Canaan witnessed a massive influx of Amorites from the north and also incursions by the Hittites and the Hurrians. As Egypt’s power waned toward the end of the New Kingdom, the Philistines came in from the sea and the Israelites from across the Jordan. All these societies were absorbed into the Canaanite culture or were themselves modified by the Canaanites. Israelite success in removing mention of the Canaanites as an identifiable entity would not be firmly established until late in the eighth century under Hezekiah.

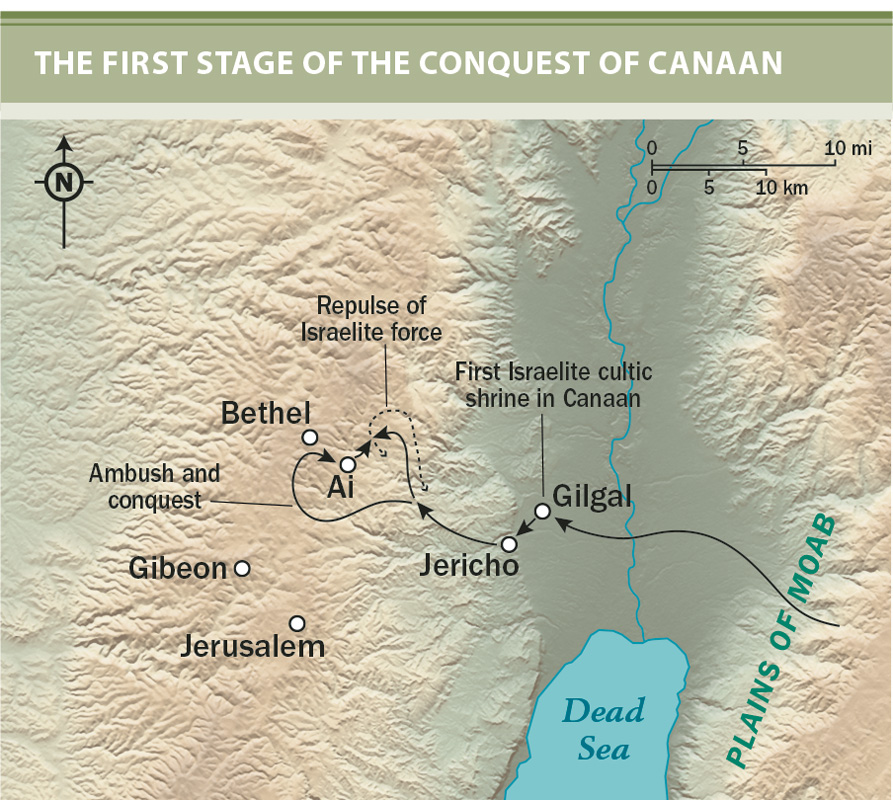

The story of Israel’s predominance in the area of Canaan begins, of course, with the infiltration into the land under Joshua and persists until the fall of the temple in AD 70 at the hands of the Romans. During that period, Canaan endured as a place of importance as a staging ground for controlling both Mesopotamia and Egypt and therefore witnessed campaigns by most of the great leaders of Assyria, Babylon, Persia, Greece, and Rome. Of course, with each campaign came alterations in both the political and the cultural landscape of the land and reinforcement of the view that the area was the center of the world. Indeed, it is in Canaan, in the Jezreel Valley, that Scripture turns its focus for the final battle between God and the forces of Satan at Armageddon.

GEOGRAPHY AND CLIMATE

Geography. Though small in scope, the region of Canaan encompassed a surprisingly wide variety of environments. Within its topography one could find perilous deserts, snow-capped mountains, thick forests, lush plains, coastal beaches, rugged hills, deep valleys, and separate water sources full of both life and minerals. The Shephelah, or coastal plain, lacks any natural harbor areas that would have led to the early exploitation of the Mediterranean in the south that is so well known in the northern areas of Phoenicia. It does, however, provide wide-open, fertile areas fed by the rain runoff from the central hill country, which allowed it to be a useful source of farming and civilization from a very early period.

The central hill country is essentially a ridge that runs parallel to the coast and undulates in elevation from the mountainous north to the rugged but less elevated regions of the south. This ridge served as a natural barrier against travel from west to east, so it is not surprising that important military towns such as Hazor cropped up in places where valleys in this ridge allowed travelers to move from the coast to the inland regions as necessary to reach Mesopotamia from Egypt. One such valley of significance through the history of the land of Canaan is the Esdraelon or Jezreel Valley. It provides a wide swath of land that moves from Akko in the west ( just north of the Carmel Range) to the Sea of Galilee in the east, with access points in the north and south. Within this valley were settlements such as Megiddo and Hazor in earlier times, and Nazareth and Tiberias in later times.

Along the eastern edge of the central hill country is the Jordan Rift Valley. The elevation drops dramatically from cities in the hill country, such as Jerusalem at about 2,500 feet above sea level, to cities in the valley, such as Jericho at about 1,000 feet below sea level, within the span of about fifteen miles. The valley itself is part of a much larger rift that starts in southeast Turkey and continues all the way to Mozambique in Africa. Waters from snowy Mount Hermon and a couple of natural springs feed into the Sea of Galilee and then flow into the Jordan River, which snakes its way down into the Dead Sea. The lands around the Jordan River were once very fertile in the north and probably included abundant forests and wildlife. Toward the south of the Jordan River, one approaches the wilderness surrounding the Dead Sea, a region well known for its mineral contents.

The southernmost section of Canaan, known as the Negev, is an unforgiving region with mountains, deserts, and interspersed oases throughout. It opens up into the Arabian Desert to the east and the Sinai Peninsula to the southwest. Its primary cities of importance in biblical times were Beersheba and Raphia. As the gateway from Egypt to Canaan, the Negev played a significant role in biblical history.

Climate. The climate of Canaan played a significant role in its religion and history. It is generally recognized that climate change played a rather momentous role in population movements by nomads, in destabilization of powerful governments, and in the capability, or lack thereof, of nations to participate in the trade that was at the heart of Canaan’s growth, spread of influence, and success. Within Canaan itself, because the natural water sources were on the wrong side of the central hill country, most of its water came from rainfall. It is not surprising, therefore, that many of the discussions that take place in both Canaanite and Israelite religious expressions concerning the power of their gods found utterance in terms of a god’s ability to grant rain (see 1 Kings 17–18). The rainy season began in October and typically continued through April. The other months of the year witnessed little or no rainfall. Although in a temperate zone within which one might expect high temperatures, the coastal plains were kept relatively cool by winds coming in off the sea. The coastal mountain areas, such as Carmel, were the most likely to receive rainfall, so when they were without it, all the land suffered (Amos 1:2).

CULTURE AND POLITICS

The history of Canaan begins with an archaeological record that travels back into the first signs of human settlement anywhere in the world. Such early attestation exists within the confines of Palestine itself at Jericho and Megiddo, both sites of natural springs that would have attracted settlers. The pre-Israelite civilizations of Canaan are well attested during the Bronze Age (c. 3300–1200 BC). Their culture as represented in the art and architecture of the land demonstrates a developed people who were metropolitan in taste and gifted in style. Furthermore, because of the placement of the land between Egypt and Mesopotamia and the numerous incursions by outside forces throughout its history, Canaan reveals a people with a high tolerance for change and a willingness to absorb other viewpoints into their perspectives and practice. Archaeological finds reveal a mixture of Egyptian, Sumerian, Amorite, Hittite, and Akkadian influences in their literature, material wealth, and religion.

Though unified in terms of a worldview and religious expression, the people of Canaan were politically committed to independent expressions of their power and influence. The greater cities seem to have served as hubs around which smaller communities and cities organized and remained separate from each other. The Amarna letters of the fourteenth century BC reveal leaders who did not trust each other and who sought the Egyptian pharaoh’s favor as they vied for position and strength. As one would expect, different city-states held more sway in different eras. Ebla flourished in the period of 2500–2000 BC and then again around 1800 BC. Likewise, Byblos flourished in the period of 2500–1300 BC. It is in the Middle Bronze Age (2200–1550 BC) that cities more directly involved with the biblical narrative started to flourish. For instance, Jerusalem, Jericho, Hazor, and Megiddo reached their height of power and influence around 1700–1500 BC, and each of these is mentioned in various texts of the time that give us some insight into Canaan’s role in the greater political history. It is Ugarit/Ras Shamra, which flourished in 1400–1200 BC, however, that has granted us the greatest amount of textual knowledge and information about the religion and literature of Canaan.

RELIGION

The excavations of Ras Shamra (beginning in 1929), and the accompanying discovery of its archive of clay tablets, granted modern scholars a perspective into Canaanite religion that had been hinted at in the biblical text but previously had remained somewhat of a mystery. The tablets themselves date between 1400 and 1200 BC. They reveal a highly developed religion with identifiable, well-defined deities. These deities represent religious practice and thought in the region that go back to at least 2000 BC, and the Mesopotamian religions they are dependent on go back well beyond that.

Canaanite deities. The primary gods identified in the text include El, Baal, Asherah (at Ugarit, Athirat), Anath (at Ugarit, Anat), and Ashtoreth (at Ugarit, Astarte). El was the supreme Canaanite deity, though in popular use the people of Canaan seem to have been more interested in Baal.

The relationship between the Canaanite use of the name “El” for their supreme god and Israel’s use of the same in reference to its own God (Gen. 33:20; Job 8:3; Pss. 18:31, 33, 48; 68:21) is something that biblical authors used at various points in their writings (Ps. 81:9–10; Nah. 1:2), never in the sense of associating the two as one and the same, but solely for the purpose of distinguishing their God, Yahweh, from any associations with the descriptions and nature of the Canaanite El (Exod. 34:14). Practically speaking, the coincidence probably resulted from the fact that the Hebrew word ’el had a dual intent in its common usage, similar to the way a modern English speaker will sometimes use “god” as either a common or a proper noun.

Like “El,” the term “Baal” had a dual function in its use. Because the word means “master” or “lord,” the people of Canaan could apply “Baal” to either the singular deity of the greater pantheon or to individual gods of a more local variety. Local manifestations included Baal-Peor, Baal-Hermon, Baal-Zebul, and Baal-Meon. The OT acknowledges the multiplicity of Baals in some places (Judg. 2:11; 3:7; 1 Sam. 7:4) but also seems to allude to a singular ultimate Baal (1 Kings 18; 2 Kings 21:3), called “Baal-Shamen” or “Baal-Hadad” elsewhere. The fact that Baal was recognized in the Ugaritic texts as the god of the thunderbolt adds an interesting insight to the struggle on Mount Carmel, in which one would suppose that had he been real, the one thing he should have been able to do was bring fire down from the sky; but he could not (1 Kings 18). Recognition that the term “Baal” could refer to a number of gods or to one ultimate god may also help one understand the syncretism that took place in Israel between Yahweh and Baal addressed by the prophet Hosea (Hos. 2:16). To the common person who recognized the multiplicity of the term “Baal” and yet also heard of his supremacy, the assignment of the name to Yahweh and the resulting combining that would occur would seem a natural progression, though still sinful in the eyes of God.

The synthesis of Baal and Yahweh is demonstrated in Scripture as being a temptation from national Israel’s earliest encounters with Baalism. The events at Peor (Num. 25) demonstrate a propensity toward this type of activity, but the confusion between Yahweh and Baal became strongest once Israel entered into the land. Gideon had a second name, “Jerub-Baal” (Judg. 6:32), and the people themselves worshiped Baal-Berith (“Baal of the covenant”) as an indication that they believed their covenant to be with Baal, not Yahweh. Saul, Jonathan, and David all had sons named for Baal: Esh-Baal, Merib-Baal, and Beeliada respectively. Jeroboam I made the connection even more explicit in his setting of shrines at Dan and Bethel with the golden calves that were common icons for Baal in the era, but that he apparently viewed as being appropriate representations of Yahweh. By the time of the prophets, such confusion evidently was entrenched into the very heart of both Israel and Judah; however, Yahweh was able to utilize the false assessments of his character to clarify his true character and ultimately bring Israel back to him.

Asherah was the wife of El in Ugaritic mythology, but apparently because of Baal’s accessibility and ubiquitous nature, she was ultimately given to Baal as a consort among Canaanites in the south. Apparently, her worship was also linked to trees, and the mentioning of “Asherah poles” (Exod. 34:13; Deut. 7:5; Judg. 6:25) in Scripture suggests that such a linkage had been stylized into representative trees at sacred locations. Asherah had prophets (1 Kings 18:19) and specific instruments of worship in Israel (2 Kings 23:4) and became so ensconced in practice and thought that her form often was replicated in the form of items known as Asherim. The previously mentioned synthesis between Baal and Yahweh seems also to have found expression regarding Asherah within Israel. At Kuntillet Ajrud a famous graffito reads “Yahweh of Samaria and his Asherah.” This example of the people granting a consort to Yahweh is yet another instance where the biblical revelation is so distinct among surrounding cultures because of the absence of such imagery regarding God.

Anath was understood as both Baal’s sister and his lover in Canaanite mythology. Given her apparent replacement in the thought of the southern Canaanite tribes by Asherah, it is not surprising that the only place we find Anath mentioned is in appellations, such as “Beth Anath” (lit., “the house of Anath” [Josh. 19:38; Judg. 1:33]). She also seems to have played a role in the tone of Baal worship in that she functioned as a goddess of both warfare and sexuality. Her portrayal in Ugaritic texts and in inscriptions from Egypt suggests a lasciviousness that has become the defining characteristic of Canaanite worship and also seems to be at the center of the methodology implemented by Hosea to reach Israel, which had become ensnarled in a similar outlook regarding Yahweh (Hos. 1–3).

The descriptions of Ashtoreth at Ugarit portray her in much the same light as Anath. Some cultures such as Egypt and later Syria seem to have even melded them together into one being. Whether this combining was a part of the Israelite conceptions is difficult to determine, although such a combination may explain why only Ashtoreth is mentioned in the biblical text as an individual deity and not Anath. In any case, Ashtoreth apparently was a primary figure in the corruption of worship during the reign of Solomon (1 Kings 11:5, 33; 2 Kings 23:13).

Summary. By the time the Israelites entered the land, they found a religion that was already well established and accustomed to absorbing various viewpoints into its expression and practice. Additionally, they found a religion that catered to the more base and animalistic tendencies to which all humanity is drawn since the fall. The commonality of such practices among almost all ancient cultures serves as a potent reminder of the distinctiveness and power of the biblical worldview. The narratives, poems, and prophetic oracles of the OT demonstrate a knowledge of these beliefs and an acknowledgment of their place in the lives of everyday Israelites, but they never demonstrate a submission to them in their portrayal of the true God and his expectations of his people.

Canal An inland waterway. The NIV uses the word to describe tributaries of the Nile (see Exod. 7:19; 8:5; Isa. 19:6) as well as various constructed waterways in Babylonia and Persia (Ezra 8:15, 21, 31; Dan. 8:2, 3).

Cananaean A rendering of Kananaios, which is a Greek transliteration of the Aramaic word for zealot, used as an epithet for the disciple Simon to differentiate him from Simon Peter (Matt. 10:4; Mark 3:18; cf. Luke 6:15; Acts 1:13 [NIV: “the Zealot”]). It is not known whether Simon belonged to the Zealots, the Jewish sect that opposed Roman rule in Palestine, or was zealously devoted to Jewish law (see Acts 21:20).

Candace See Kandake.

Candle, Candlestick The KJV renderings of Hebrew words (ner; menorah) translated “lamp” and “lampstand” in most modern versions. The terms can refer to a candle, lamp, torch, or other such device that provides light, or to the source to hold such light. The Greek word lychnos, usually translated “lamp,” sometimes is used figuratively as Christian conscience (cf. Matt. 5:14–15).

Cane See Calamus.

Canker This term appears in the KJV translation of 2 Tim. 2:17; James 5:3, involving two different Greek words. A canker is any source of corruption or debasement. In 2 Tim. 2:17 the word is gangraina, referring to a disease involving inflammation and spreading ulcers. Modern translations read “gangrene,” the local death of body tissues due to loss of blood supply. In James 5:3 the word is katioō, which refers to the corrosion of metal, in this case silver and gold. Modern translations read “corroded” or “rusted.”

Cankerworm The KJV translation in Joel 1:4; 2:25; Nah. 3:15–16 of the Hebrew word yeleq, which refers to a species of wingless, creeping locust. In Ps. 105:34; Jer. 51:14, 27 the KJV renders the word as “caterpillar.” See also Locust.

Canneh See Kanneh.

Canon See Bible Formation and Canon.

Canticles See Song of Songs, Book of.

Cap See Bonnet.

Caperberry Grown in rock clefts and on walls in Palestine, the caperberry was a common prickly shrub. Its large, white flowers with brightly colored stamens produced small, edible berries. Their repute as excitants of sexual desire is ancient and widespread. The word appears only in Eccles. 12:5 (NASB, NET), where it is used to allude to declining sexual potency that comes with advancing age. Some English versions, picking up on the allusion, simply refer to “desire” waning rather than to the berry itself (NIV, NRSV).

Capernaum A fishing town located on the northwest shore of the Sea of Galilee (Matt. 4:13). Capernaum is referred to in Luke 4:31 as a polis (“city” or “town”), so it must have been larger than a typical “village.” The town was on an important trade route and was a center for commerce in Galilee. In Capernaum, Jesus called Levi (Matthew) from his “tax booth,” probably a customs station for goods in transit (Mark 2:13–17; Matt. 9:9–13; Luke 5:27–32). There may also have been a military garrison in Capernaum, since the town’s synagogue was built by a certain centurion whose servant Jesus healed (Matt. 8:8–13; Luke 7:1–10).

Capernaum served as Jesus’ base of operations during his Galilean ministry. In Mark’s Gospel, Jesus’ teaching and healing ministry begins there (Mark 1:21–34), and this is where he returned “home” after itinerant ministry around Galilee (Matt. 9:1; Mark 2:1; 9:33). Although Peter and Andrew were originally from Bethsaida (John 1:44), they lived in Capernaum, and their fishing business was located there. It was here that Jesus healed Peter’s mother-in-law (Mark 1:29–31) and a paralyzed man whose friends lowered him through a hole in the roof (2:1–12). Jesus later pronounced judgment against the town, together with Chorazin and Bethsaida, because of the people’s unbelief despite the miracles they had seen (Matt. 11:23–24; Luke 10:15). Archaeologists have discovered a first-century home under a fifth-century church in Capernaum. Christian inscriptions in the home indicate that it was venerated by Christians, suggesting to many scholars that this was Peter’s residence.

Artist’s rendition of the house of Peter at Capernaum

Caphtor A place referred to in Deut. 2:23; Amos 9:7 as the original home of the Philistines. Jeremiah refers to the Philistines as “the remnant from the coasts of Caphtor” (Jer. 47:4). The location of Caphtor is uncertain but is widely accepted to be Crete. See also Caphtorites.

Caphtorites According to Gen. 10:13–14; 1 Chron. 1:11–12 (NRSV: “Caphtorim”), a group of people descended from Noah’s son Ham through Mizraim (“Egypt”). Elsewhere they are identified with the Philistines, who inhabited an area north of Egypt on the southern coast of Canaan (Jer. 47:4; Amos 9:7). According to Deut. 2:23, the Caphtorites migrated and dispossessed the land of the Avvites, which reached to the coast of Canaan as far west as Gaza. See also Caphtor.

Capital Punishment The government-sanctioned killing of a perpetrator of a serious offense. The biblical portrayal of capital punishment involves the concept as a God-ordained institution related to the value of humanity and the necessary recompense for the corruption or murder of that ideal (Gen. 9:6).

Methods of capital punishment. The methods of capital punishment listed in the Scriptures are several. The most common method was stoning (Lev. 24:16; Num. 15:32–36; Deut. 13:1–10; 17:2–5), and this required that the primary witnesses for the prosecution be the first to take up stones against the accused. The burning of a person was rare, but it was commanded for certain sexual crimes (Lev. 20:14). In the story of Judah and Tamar, before learning the true nature of her pregnancy, Judah ordered his daughter-in-law to be burned to death outside the city (Gen. 38:24). On occasion, the method of punishment involved being run through by a weapon: Phinehas impaled an Israelite and his Midianite lover with a spear in order to soothe the wrath of God and stop a plague (Num. 25:7–8); Canaanites under the kherem (divine command of total destruction) were to be put to the sword (Deut. 13:15), and God commanded that anyone who touched Mount Sinai be shot through with arrows (Exod. 19:13). Beheading seems to have been practiced for crimes against royalty, though there are no mandates concerning it (2 Sam. 16:9; 2 Kings 6:31–32). Other forms of capital punishment included impalement or placement upon a wooden stake (Ezra 6:11; Esther 2:23). Although some understand this to be a form of hanging, archaeological evidence and understandings of the cultures of the time suggest that impalement is more likely. Finally, the Romans took the punishment of crucifixion that they had learned from Carthage and applied it with vigor to those guilty of insurrection (Luke 23:13–33).

Offenses leading to capital punishment. With respect to Israel, the list of offenses deemed worthy of capital punishment primarily focused upon human interrelations, though a few crimes listed did involve the breaking of covenant stipulations involving one’s direct relationship with God. From this latter group, crimes such as witchcraft and divination (Exod. 22:18; Lev. 20:27; Deut. 18:20), profaning the Sabbath (Exod. 31:14–17), idolatry (Lev. 20:1–5), and blasphemy (Lev. 24:14–16; Matt. 26:65–66) were included. In these laws one sees the expression of God’s wrath and jealousy for his position in the lives of those who claim to be his. Mandates demanding death in response to some sort of corruption of the human ideal included acts such as costing another person his or her life, sexual aberrations, and familial relationships. Anyone who committed murder (Exod. 21:12), put another’s life at risk by giving false testimony in a trial (Deut. 19:16–21), or enslaved a person wrongfully (Exod. 21:16) could be considered to have cost someone’s life. Sexual aberrations regarded as worthy of death included sexual acts of bestiality, incest, and homosexuality (Exod. 22:19; Lev. 20:11–17), rape (Deut. 22:23–27), adultery (Lev. 20:10–12), and sexual relations outside of marriage (Lev. 21:9; Deut. 22:20–24). The final group of familial relationships primarily applies to the crass rebellion of children against their parents (Deut. 21:18–21).

At times, the righteous faced capital punishment for their beliefs. For example, at the hands of government faithful saints of God were sawn in two (Heb. 11:37 [a Jewish tradition may indicate that the prophet Isaiah died in such a manner]), stoned (Acts 7:58–59), and beheaded (Mark 6:27; Acts 12:2). At other times, attempts were made to inflict such punishment, but God intervened. In these examples, the punishments that God prevented include consumption by lions (Dan. 6), burning in a fiery furnace (Dan. 3), being thrown over a cliff (Luke 4:29–30), and stoning (Acts 14:19).

Capital punishment today. Several opinions persist regarding the appropriateness of continuing the practice of capital punishment in the modern era. For some, passages expressing a command concerning such types of punishment are either descriptive of what was going on or fall under the principle of a culture that no longer exists, so their laws are no longer relevant. Indeed, few today would enforce capital punishment for the same crimes that Israel punished with death. For these individuals, the question then becomes whether Scripture, which required capital punishment at the time it was written, permits capital punishment today. Those who are consistent will admit that if there is no mandate to require it, it must also be admitted that there is no mandate preventing its use as well.

On the other side are those who argue that while one cannot directly apply the laws of the OT to today’s situation, the principle expressed, particularly as it pertains to value of humanity, demands the continuation of capital punishment at least in response to heinous crimes that cost an individual his or her life, either literally as with murder, or more figuratively (but just as real) as with rape. For these people, it is significant that the requirements of capital punishment for murder precede the giving of the law (Gen. 9:6). Since the status of humanity in the eyes of God has not altered, neither has his prescribed method of dealing with those crimes been lifted; here the principle requires the practice (Rom. 13:4).

The answers are not easy, but they are important. The biblical text itself regularly balances the expected payment for sins worthy of the death penalty with expressions of grace (Gen. 4:15; Josh. 6:22–23). Furthermore, one must account for the perfect knowledge of God and his execution of his fully justified wrath in contrast to the imperfect knowledge of humanity and the inequalities that sometimes find expression in modern court settings. Finding the balance between holding a biblical worldview that appropriately seeks justice and one regulated by grace is difficult enough in terms of interpersonal relationships; when it is moved to the greater scope of society as a whole, the questions are even more significant and even more difficult to answer. See also Crimes and Punishments.

Capitals See Chapiter.

Cappadocia In ancient times, a sparsely populated region primarily comprised of a large, high-altitude plateau in what is present-day central-eastern Turkey. The geographical region of Cappadocia was bordered in the north by the region of Pontus, in the east by the headwaters of the Euphrates River and portions of the Taurus Mountains, which also served as the region’s southern boundary, and in the west by the regions of Pisidia and southwestern Galatia. Cappadocia marks the easternmost boundary of the broader region known today as Asia Minor, and thus it serves as a geographical point of transition between Europe and Asia. The Gospels are set in a time when Cappadocia was a Roman province, which it became in AD 17 under the emperor Tiberius (42 BC–AD 37). During this period, the region had few centers of urban life, and the majority of the population lived in small, widely scattered villages. Residents of Cappadocia are present in Jerusalem at Pentecost (Acts 2:9), and Christians in various regions of the Roman Empire, including Cappadocia, are greeted in the salutations at the beginning of 1 Peter (1:1).

Capstone In the NIV “capstone” appears twice (Zech. 4:7, 10). Zechariah 4:7 uses the phrase ha’eben haro’shah, meaning “uppermost stone.” In Zech. 4:10, the NIV interprets ha’eben as another reference to the capstone, although most other translations understand this as the weight suspended from a plumb line. See also Cornerstone.

Captain (1) A leader appointed over a division of soldiers; a commander over the king’s bodyguard; the officer in charge of the Jewish guards for the temple (Acts 4:1). (2) A sea captain (KJV: “shipmaster”). In Jonah 1:6, a non-Israelite captain asks Jonah to call on God to save their imperiled ship. In John’s vision in Revelation (18:17), sea captains are among those who will witness and lament the destruction of Babylon, the source of their wealth.

Captain of the Temple A Jewish priestly officer whose duties included maintaining the purity of the Jerusalem temple. Such officers were agents of the Jewish high priest authorized to engage in basic police and disciplinary functions. In the Gospels, officers of the temple guard were part of the conspiracy to kill Jesus (see Luke 22:4, 52). In Acts, a captain of the temple is mentioned twice in connection with attempts to suppress the popular preaching of the apostles in Jerusalem, usually near the temple (see Acts 4:1; 5:24).

Captivity A term used to refer to Judah’s exile to Babylon in 587–539 BC. See also Exile.

Caravan Prior to the rise of Roman roads, travel in the ancient Near East was extremely dangerous. For protection, large groups of people and animals traveled together in caravans, especially for trade purposes. Most OT examples are of Arabian caravans of camels carrying spices and other valuables (e.g., Judg. 6:5; 1 Kings 10:1–2; Isa. 21:13; 60:6). Abram travels from Ur to Canaan in a large caravan (Gen. 12). In Gen. 37:25 an Ishmaelite caravan buys Joseph into slavery.

Caraway The seeds of the caraway (Heb. qetsakh; NRSV: “dill”) plant (Nigella sativa, not Carum carvi) were used as a condiment on bread and were known to ease intestinal gas. As Isa. 28:25–27 describes, light beating freed the seeds without crushing them.

Carbuncle In several OT lists of gems, older English versions translate some Hebrew gemological terms as “carbuncle.” In Exod. 28:17; 39:10 the word refers to one of the stones set in the priestly “breastpiece for making decisions” (28:15). In Isa. 54:12, translating a different Hebrew term, the restored city of Zion has “gates of carbuncles” (KJV, RSV; NIV: “gates of sparkling jewels”; cf. Rev. 21:21), as does the gem-laden “garden of God” in Ezek. 28:13. The identification in modern terms of gemstones mentioned in the Bible is often difficult. Ancient versional evidence suggests that the biblical carbuncle was a red stone, possibly a garnet.

Carcas See Karkas.

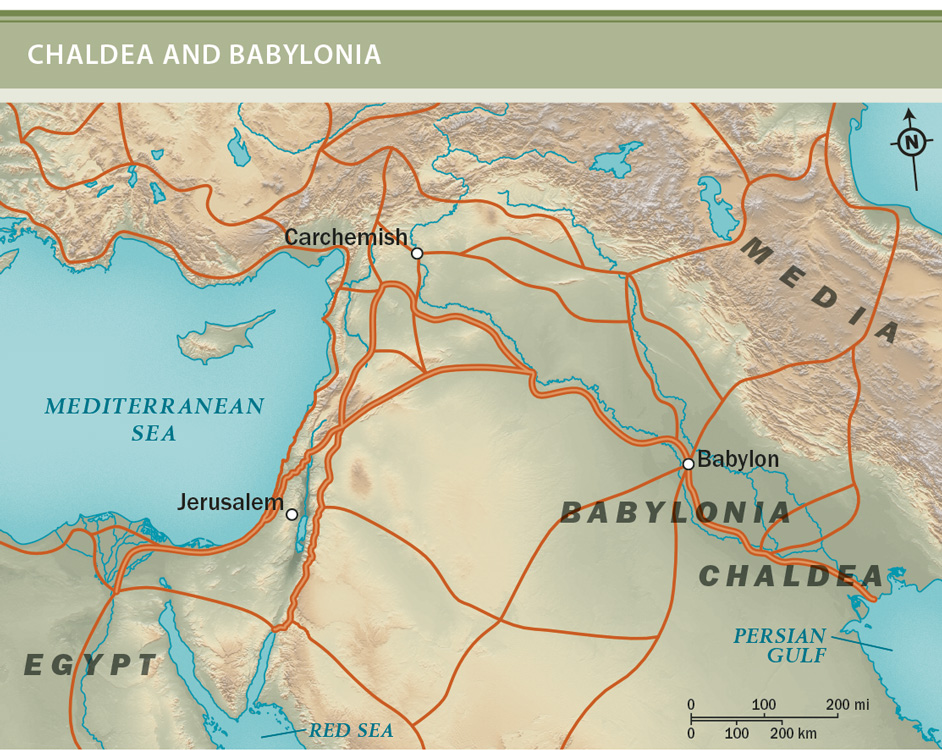

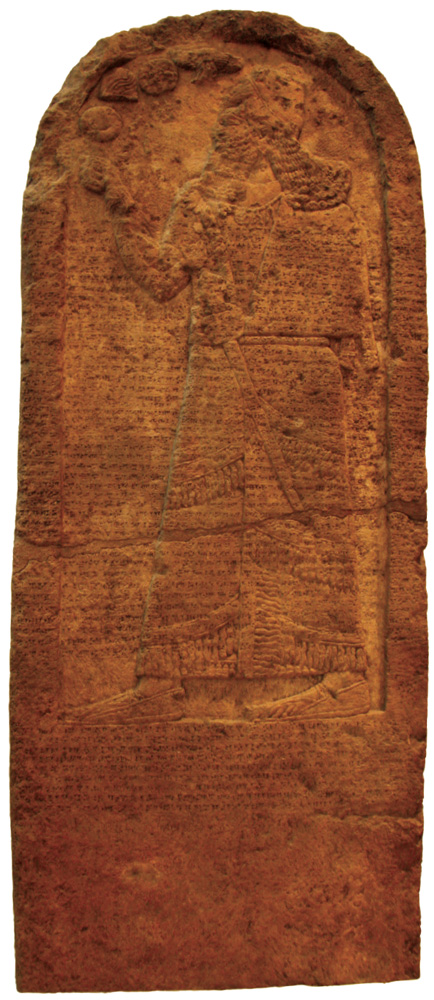

Carchemish An ancient city predating biblical times. It was situated on the very northern portion of the Euphrates River, on its bend southward. The name means “fortress of Chemosh,” the god of Moab.

Most relevant to the OT, Carchemish was for a time under Hurrian influence until it came under Hittite control by the thirteenth century BC. Then, in the wake of the sweeping invasions of the Sea Peoples, the Hittite kingdom was destroyed, leaving Carchemish to perpetuate Hittite culture. The kingdom of Carchemish developed into an independent military entity of its own and was able to resist Assyrian expansion until its defeat by Sargon II in 717 BC.

There are three biblical references to Carchemish: 2 Chron. 35:20; Isa. 10:9; Jer. 46:2. In Isa. 10, in the midst of Isaiah’s oracles of judgment against Israel, God declares that Assyria is “the club of my wrath” (v. 5), whom he will send to punish his faithless people. Assyria, however, has other plans, “to put an end to many nations” (v. 7). Assyria boasts of its might and compares its defeat of Kalno (in Syria) to the fall of Carchemish (v. 9), likely referring to its defeat at the hands of Sargon II.

The other two texts refer to a very important event in Israel’s history. According to Jer. 46:2, it was in the fourth year of Jehoiakim (605 BC). Assyrian dominance of Mesopotamia was about to come to an end at the hands of the Babylonians under Nebuchadnezzar. The Egyptian pharaoh Necho II, wishing to maintain a buffer state between his land and this rising superpower, brought his armies to Carchemish in an effort to save the Assyrians.

According to 2 Chron. 35:20–36:1, King Josiah of Judah met Necho along the way and engaged him in battle. Necho was reluctant, as he had no quarrel with Judah, but Josiah was persistent, apparently thinking that an alliance between Judah and Babylon would be to his advantage. Josiah was shot by archers in battle and died in Jerusalem. Apparently, by the time Necho reached Carchemish, the remnant Assyrian army was defeated, and Nebuchadnezzar proceeded to defeat Necho. As a result, the city of Carchemish never fully recovered. But more important, this battle was decisive in swinging the balance of power away from Egypt and Assyria and toward Babylon, at whose hands Judah would, within a decade, start to be taken into exile. Jeremiah recounts Egypt’s defeat in Jer. 49:2–12.

Careah See Kareah.

Career Decisions Scripture lays down certain principles for making major life decisions. The key principle that should guide one’s decision is the desire to faithfully use one’s God-given endowments (see Matt. 25:14–30). Thus, one should be motivated by love for God and a desire to glorify him in one’s work (1 Cor. 10:31). In his providence, God has endowed every person with a unique combination of ability, life experience, and temperament. Not every career demands the same degree of creativity, but every job assumes an element of creative ability.

We discover this by first asking, “What types of needs in the community am I drawn to?” To narrow it down a bit more, we ask, “Do I like working with ideas, with things, with people, or with data?” Desire is the initial spark that usually leads one to pursue a particular career path.

Since one’s gifting is essential to determining what career would be a good fit, we should also ask, “What am I good at?” For example, it takes a combination of leadership gifts and people skills to work efficiently in a management position.

Finally, since certain opportunities fit one’s personality more than others, one should determine what work environment values are most important (e.g., intellectual stimulation, adventure, creativity). A career assessment often is useful in discerning which career is a good fit.

Carites Mercenaries in the service of the house of David. The priest Jehoiada called on them to rid the land of Athaliah (2 Kings 11:4, 19). At one time they were thought to be foreign mercenaries (the Carians who served the Egyptians in the seventh and early sixth centuries BC), but this view is not widely held today. Although the name also occurs in the Hebrew text of 2 Sam. 20:23, most follow the Qere, which reads “Kerethites.”

Carkas See Karkas.

Carmel Not to be confused with the coastal mountain in northern Israel, Carmel was a city in Judah, near Hebron, and was associated with several stories in the Bible. In 1 Sam. 15:12 Saul visits Carmel and erects a monument. Carmel was the home of Nabal, the first husband of David’s wife Abigail (1 Sam. 25:2), and of Hezro, a member of his entourage (2 Sam. 23:35; 1 Chron. 11:37).

Carmel, Mount The wooded mountain promontory on the Mediterranean, near modern Haifa. The name means “the garden.” It forms a northern barrier to the coastal plain of Sharon. Mount Carmel provided the perfect stage for its most significant event, the confrontation between Elijah and the prophets of Baal (1 Kings 18), the god of storms and therefore agricultural produce. The mountain’s high elevation meant that it was lush until a drought. When the prophets threatened that Carmel would wither, conditions were extreme (Isa. 33:9; Amos 1:2; Nah.1:4).

Mount Carmel

Carmelite An inhabitant of the city of Carmel in the hill country of Judah (Josh. 15:55). Most notable among those who hail from Carmel is David’s wife Abigail (1 Sam. 27:3; 1 Chron. 3:1). The KJV uses the term “Carmelitess” to describe Abigail.

Carmi See Karmi.

Carmites See Karmites.

Carnal The KJV translation of certain Greek constructions referring to “flesh.” Most contemporary English versions prefer “of the flesh,” “earthly,” “worldly,” and even “sinful.” Occasionally “carnal” simply refers to physical or material things (e.g., Rom. 15:27; 1 Cor. 9:11) or to certain aspects of the OT that have been fulfilled in Christ (Heb. 7:16; 9:10). The notion occurs most frequently in the writings of Paul, who makes special use of “carnal” to contrast it with “spiritual.” In Rom. 8:1–11 Paul presents the carnal or worldly person as “Spirit-less” and therefore “Christ-less.” By definition, a Christian is spiritual and cannot be carnal (“live according to the sinful nature” [8:4]). That is, those who have Christ necessarily have the Holy Spirit, and therefore they do not follow the pattern of the world, but rather walk by the Spirit and produce spiritual fruit (Gal. 5:16–26).

In other contexts the same apostle can describe Christians as “carnal” (KJV) or “worldly” (NIV). “Brothers, I could not address you as spiritual but as worldly—mere infants in Christ. . . . For since there is jealousy and quarreling among you, are you not worldly?” (1 Cor. 3:1–3). Here Paul rebukes the Corinthian Christians for their immaturity. The Spirit has sanctified them (6:11), but in their sinful pride and divisiveness they appear to belong to the world, the evil age of sin and death. They must “grow up” so that their conduct befits the Spirit, who now dwells in them.

Although Paul’s two uses of “carnal” seem opposed to each other, he is simply calling his Corinthian readers to live consistently with the truths that he expounded in Romans. Christians are fundamentally not carnal, but spiritual. They should therefore act like it in a life marked by faith, hope, and especially love (1 Cor. 13). These are the true signs that someone has the Holy Spirit, even though the Christian may lapse into attitudes and behaviors inconsistent with this new identity in Christ.

Carnelian A precious red stone. It is one of the jewels in the high priest’s breastpiece (Exod. 28:17; 39:10), as well as in the “covering” (similar to the high priest’s breastpiece) for the king of Tyre, who is portrayed as a priest serving in the temple garden of Eden (Ezek. 28:13 NRSV). In the book of Revelation, God, who sits on the throne, has the appearance of carnelian (4:2–3), and carnelian is one of the precious stones in the walls of the new Jerusalem (21:20).

Carpenter The traditional translation of the Greek term tektōn, which refers to someone skilled in working with stone, iron, copper, or wood. Both Jesus (Mark 6:3) and Joseph his father (Matt. 13:55) were “carpenters” (i.e., craftsmen).

Carpus An acquaintance in Troas to whom Paul had entrusted his cloak, books, and parchments. While imprisoned in Rome, Paul asks Timothy to retrieve them from Carpus (2 Tim. 4:13).

Carriage Solomon appears in a carriage as he arrives for his wedding in Song 3:7, 9. This carriage may be a palanquin (KJV), an enclosed transportation platform without wheels, on poles, carried by porters. The two synonymous underlying Hebrew words may also be translated sedan chair or ornamental litter.

Carrion Vulture See Vulture.

Carshena See Karshena.

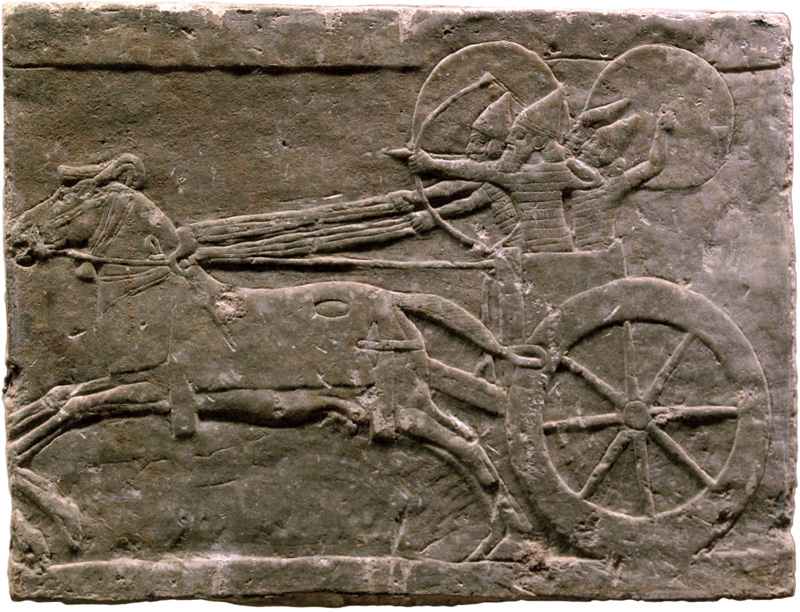

Cart In biblical times, a wheeled vehicle, usually drawn by animals such as oxen and cows and used in agricultural contexts (Num. 7:3; 1 Sam. 6:7; Isa. 28:27; Amos 2:13). The Hebrew word ’agalah can be translated as “cart” or “wagon.” Carts were used to transport objects, but the hilly terrain of Palestine was not conducive to their use (cf. 2 Sam. 6:3–6; 1 Chron. 13:7–9). Thus, they were used primarily in the plains of Palestine (1 Sam. 6:7–8, 10, 11–14). The cart or wagon likely was of Assyrian origin.

Casement Type of wall fortification used during the late Iron Age, popular during the ninth and tenth centuries BC. It is made of a double wall forming a series of rooms that could be filled in quickly with rubble to reinforce them if an attack was looming. In times of peace these rooms were often incorporated into houses built against the walls.

Casiphia See Kasiphia.

Casluhites See Kasluhites.

Cassia A cinnamon-like spice mentioned three times in the OT (Exod. 30:24; Ps. 45:8; Ezek. 27:19 [cf. Gk. kinnamōmon in Sir. 24:25]; Heb. qiddah, qetsi’ah). In the Exodus passage it is prescribed as a component for the sacred anointing oil. In Ps. 45 the king’s robes are described as being fragrant with cassia and other spices. Ezekiel speaks of it being an item valuable for trading. The spice is derived from the inner bark of a tree that is native to India and modern-day Sri Lanka. See also Cinnamon.

Castaway Someone who is shipwrecked and stranded on land for an extended period of time. In his trial before Porcius Festus, Paul appeals to be tried by the imperial courts in Rome (Acts 25:11–12). Acts 27:6–28:11 tells the story of part of Paul’s journey to await this trial. A grain transport ship carrying Paul, a centurion, and additional Roman soldiers, as well as numerous other prisoners, is caught in a severe storm, in fulfillment of Paul’s prophetic warning. The ship eventually runs aground on a sandbar on the island of Malta, where it is smashed to pieces by the pounding surf, forcing the passengers to swim to shore using pieces of the wreckage. There they stay as castaways for three months, sustained through the generosity of the island’s chief official, Publius. Paul heals many of the sick in Malta during this time. In 2 Cor. 11:25 Paul mentions having experienced three shipwrecks during his ministry.

“Castaway” is also an older translation for the Greek word adokimos, which the NIV variously renders as “depraved” (Rom. 1:28), “disqualified” (1 Cor. 9:27), “rejected” (2 Tim. 3:8), “unfit” (Titus 1:16), and “worthless” (Heb. 6:8). It is also used of those who “fail the test” of Jesus Christ living in them (2 Cor. 13:5–7). In each instance the word describes those who live contrary to the gospel.