N

Naam A son of Caleb the son of Jephunneh, he belonged to the tribe of Judah and was listed in Judah’s genealogy (1 Chron. 4:15).

Naamah (1) The daughter of Lamech and Zillah and the sister of Tubal-Cain, the bronze and ironworker mentioned in Cain’s genealogy (Gen. 4:22). (2) The mother of King Rehoboam of Judah and therefore one of Solomon’s many wives. The texts list her as an Ammonite (1 Kings 14:21, 31; 2 Chron. 12:13). (3) A town located in the lowlands of Judah near Lachish, it was in the allotment of the tribe of Judah (Josh. 15:41).

Naaman (1) A grandson of Benjamin and the founder of the Naamites (Num. 26:40; 1 Chron. 8:4; see Gen. 46:21). (2) A Syrian military commander healed of leprosy after reluctantly following Elisha’s command to dip himself seven times in the Jordan River (2 Kings 5). Jesus referred to Naaman as a model of faith (Luke 4:27). (3) A descendant of the Benjamite Ehud, he was a family head (1 Chron. 8:6–7).

Relief of a Syrian warrior (Hadatu, Syria, ninth century BC). Naaman was a Syrian military commander (2 Kings 5).

Naamathite The tribal affiliation of Zophar, one of Job’s three friends (Job 2:11; 11:1; 20:1; 42:9), best identified with the Sabean tribe of the same name in southern Arabia.

Naamites A clan descended from Naaman from the tribe of Benjamin, present at the time of the second wilderness census (Num. 26:40).

Naarah (1) One of the two wives of Asshur, the father of Tekoa; she bore him four sons (1 Chron. 4:5–6). (2) A city near Jericho, on the border of Ephraim (Josh. 16:7 [KJV: “Naarath”]), probably the same city as Naaran (1 Chron. 7:28). It is usually identified with Tel el-Jisr.

Naarai One of David’s elite warriors, a son of Ezbal (1 Chron. 11:37). He is known as Paarai in 2 Sam. 23:35.

Naaran, Naarath See Naarah.

Naashon See Nahshon.

Nabajoth See Nebaioth.

Nabal A wealthy landowner in Carmel, Nabal, gruff and hard, was married to the beautiful and intelligent Abigail. Nabal treated David contemptuously, even though David had protected Nabal’s shepherds and possessions. Abigail interceded to keep David from avenging the insult. When Nabal heard, he apparently died of shock, so David took the virtuous Abigail as his wife (1 Sam. 25:2–42).

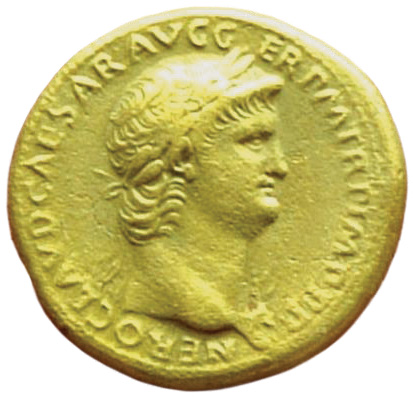

Nabateans A Semitic people group inhabiting territory south of the Dead Sea, bordering Judea. The terrain and climate forced them to become experts in water control in agriculture. The probable first mention of this group is from 312 BC in conjunction with Antigonus, who oppressed the Nabatean capital, Petra. The book of 2 Maccabees chronicles the kings of the Nabateans (Arabians) and references Aretas I (2 Macc. 5:8). In 40 BC Herod the Great, whose mother was Nabatean, escaped to Petra because the Parthians attacked Jerusalem. Later, Herod Antipas married the daughter of Aretas IV but subsequently divorced her to marry Herodias. It is this Aretas IV whom Paul references when he describes his escape over the wall in a basket in Damascus (2 Cor. 11:32).

Coin of Aretas IV, king of the Nabateans (c. 9 BC–AD 40)

Nabonidus The last king of Babylon (r. 555–539 BC), Nabonidus was a devoted worshiper of the moon god Sin, which angered the priests of Marduk, chief god of Babylon. He spent ten years in Teima, leaving his son Belshazzar as acting regent in Babylon. Nabonidus is not mentioned in the Bible.

Nabopolassar Nabopolassar was a Chaldean who established the Neo-Babylonian Empire, which lasted until Babylon’s fall in 539 BC. He began his revolt against Assyria in 626 BC. When the Medes attacked the Assyrian city Assur in 615 BC, Nabopolassar assisted at the end. A coalition continued over several years, defeating Assyria’s capitals as it retreated west. Assyria turned to Egypt’s Pharaoh Necho for help. Necho took Gaza, battled Josiah at Megiddo (2 Kings 23:29–30), and advanced to Carchemish. Nabopolassar’s son, Nebuchadnezzar, defeated Egypt in 605 BC, the same year Nabopolassar died.

Naboth A Jezreelite of Samaria, he owned a vineyard near the palace of King Ahab in Jezreel. Since Ahab desired to have this vineyard, he asked Naboth to sell or trade it. Naboth refused, in keeping with the law of inheritance (Lev. 25:23). The sullen Ahab reported this to his wife, Jezebel, who succeeded in having Naboth killed by the slander of false witnesses. After Naboth’s death, Ahab took possession of the vineyard. The prophet Elijah predicted the judgment of Ahab and Jezebel for this action, the fulfillment of which came as Ahab’s blood was licked by dogs in Jezreel, as Ahab’s descendant Joram was left for dead in this same vineyard (2 Kings 9:22–26), and as Jezebel met a violent end so that the dogs licked her blood (2 Kings 9:33–37).

Nachon See Nakon.

Nachor See Nahor.

Nacon See Nakon.

Nadab (1) The firstborn son of Aaron (Exod. 6:23). He served in the priesthood with his father and his brother Abihu (Exod. 24:1). Leviticus 10 notes that Nadab and Abihu offered forbidden fire with the incense. God subsequently destroyed them with fire. Since Nadab and Abihu had no sons, Eleazar and Ithamar, the other two sons of Aaron, served in their stead (1 Chron. 24:1–2). (2) The son of Jeroboam, he became king of Israel upon his father’s death in the second year of King Asa of Judah (1 Kings 14:20; 15:25). Nadab did evil, as did his father, in his two-year reign. Baasha of the tribe of Issachar assassinated him and reigned in his stead (1 Kings 15:25–28). (3) A son of Shammai and the father of Seled and Appaim (1 Chron. 2:28–30), from the tribe of Judah. (4) A son of Jeiel, his brother Ner was the grandfather of King Saul (1 Chron. 8:29–33).

Naggai An otherwise unknown postexilic ancestor of Jesus mentioned only in Luke 3:25 (KJV: “Nagge”) as the son of Maath and the father of Esli.

Nag Hammadi A town in Egypt near the location of a 1945 archaeological discovery in which numerous gnostic Christian texts were found, including works such as the Gospel of Thomas, the Apocryphon of James, the Gospel of Truth, the Gospel of Philip, the Dialogue of the Savior, the Apocalypse of Peter, and many others. Nag Hammadi is located over three hundred miles south of Cairo along the Nile River. A group of Egyptian peasants found thirteen papyrus manuscripts at the base of a cliff, and they contained a total of over fifty different works. Nearly all of these writings are gnostic Christian in nature, though a few, such as Plato’s Republic, are not. The manuscripts, dated to the fourth century AD, are written in Coptic (an Egyptian language, written using an adapted Greek alphabet) and are in codex (book) form. They are currently housed in the Coptic Museum in Cairo.

GNOSTICISM

Commonly referred to as the Nag Hammadi Library, this group of texts has shed a great deal of light on the early Christian gnostic movements that were present during the second through fourth centuries AD and beyond. While some early church fathers provided commentary and criticism of gnosticism in their own works, the Nag Hammadi discovery has provided the opportunity to see firsthand the writings and thought of this movement, which was branded heretical by many of the earliest Christian leaders.

The term “gnosticism” derives from the Greek word for “knowledge” (gnōsis). Gnostics, then, were those who placed an emphasis on knowledge, often of a secret or hidden nature. Saving knowledge, according to gnostic belief systems, comes by revelation from a transcendent realm. This revelation typically is available through a revealer who comes to show people the true knowledge of God and self, the two of which are often intertwined, since gnostics consider the true self to be of divine origin. Salvation of the self includes returning to the divine world from which it came. Therefore, in Christian versions of gnosticism Jesus is portrayed as the revealer of this hidden knowledge needed for salvation, the returning of the self to its divine origin. The gnostic movement was not confined to Christianity, as gnostics quite often adapted their myths to make them compatible with other religions with which they came into contact.

THE GOSPEL OF THOMAS

Among the writings found at Nag Hammadi, the Gospel of Thomas is the best known. It contains a collection of 114 sayings attributed to Jesus. Unlike the NT Gospels, the Gospel of Thomas contains no narrative material; Jesus performs no miracles or healings, none of his travels are described, and there is no passion or resurrection story. Instead, it contains only a list of Jesus’ sayings, with the occasional reply or question from his disciples. This has led some to conclude that the Gospel of Thomas is similar in genre to the hypothetical Q document, which may have been a source for the Gospel of Matthew and the Gospel of Luke. However, even Q allegedly includes some narrative material (e.g., Matt. 4:1–11 // Luke 4:1–13; Matt. 8:5–13 // Luke 7:1–10).

Many of the sayings in the Gospel of Thomas have parallels in the NT Gospels, including the following:

Jesus said, “Often you have desired to hear these sayings that I am speaking to you, and you have no one else from whom to hear them. There will be days when you will seek me and you will not find me.” (Gos. Thom. 38; cf. John 7:32–36)

Jesus said, “Whoever blasphemes against the Father will be forgiven, and whoever blasphemes against the Son will be forgiven, but whoever blasphemes against the Holy Spirit will not be forgiven, either on earth or in heaven.” (Gos. Thom. 44; cf. Matt. 12:31–32; Mark 3:28–30; Luke 12:10)

Jesus said, “Show me the stone which the builders have rejected. That one is the cornerstone.” (Gos. Thom. 66; cf. Mark 12:10–11)

Because of these similarities, the question has arisen concerning the relationship between the Gospel of Thomas and the NT Gospels. Some have suggested that, in fact, the Gospel of Thomas is the earliest of all the Gospels. This claim has been rejected by the overwhelming majority of scholars, who have instead concluded that the Gospel of Thomas reflects a later development of the sayings of Jesus that have been largely shaped out of a desire to reflect gnostic ideas. The strong gnostic theology prevalent in the Gospel of Thomas is on display in, for example, sayings 83 and 84:

Jesus said, “Images are visible to people, but the light within them is hidden in the image of the Father’s light. He will be disclosed, but his image is hidden by his light.”

Jesus said, “When you see your likeness, you are happy. But when you see your images that came into being before you and that neither die nor become visible, how much you will have to bear!” (Gos. Thom. 83–84)

APOCRYPHAL GOSPELS AND APOCALYPSES

Other apocryphal Gospels are among the works found at Nag Hammadi. The Gospel of Truth is not of the Gospel genre per se, but rather its title reflects the text’s claim to be telling the “good news” of the salvific work of Jesus, albeit from the perspective of early gnosticism. The Gospel of Philip is concerned primarily with the issue of sacraments within a gnostic understanding of human existence after physical death. In the Gospel of Mary there is a dialogue between the risen Jesus and his disciples, which is followed by Mary Magdalene receiving a special revelation from the Savior.

In addition to Gospels, the Nag Hammadi texts include several apocalypses, including the Apocalypse of Paul, the First Apocalypse of James and the Second Apocalypse of James, the Apocalypse of Adam, and the Apocalypse of Peter. These generally purport to give an account of a revelation seen by a well-known figure, especially an apostle (e.g., Peter, James, Paul). None of these works are considered to be accounts of the actual apostles; rather, they were written pseudonymously.

Nahalal A Levitical city, one of four given to the Levites from the tribal allotment of Zebulun (Josh. 21:35). Nahalal also appears in Josh. 19:15, where it is listed as a city located within Zebulun’s allotted boundaries, and in Judg. 1:30, which states that Zebulun failed to remove the Canaanite occupants of the city. Possible site locations include Tell el-Beida, which sits on the Esdraelon Plain, and Tell en-Nahl, which is on the Acco Plain. Tell en-Nahl is generally the preferred location, although it is outside of Zebulun’s traditional boundaries.

Nahaliel One of Israel’s stopping places across the Jordan prior to entering the promised land (Num. 21:19). Its name means “stream of El [God]” or “palm grove of El.” It has been identified with Wadi Wala, which flows into the Arnon River from the north, or with Wadi Zarqa Ma’in, which flows into the Dead Sea.

Naham The brother of Hodiah’s wife, in the tribe of Judah (1 Chron. 4:19).

Nahamani A leader of the Jews who returned to Judah with Zerubabbel after the exile (Neh. 7:7).

Naharai One of David’s thirty mighty warriors, he is described as a Beerothite and the armor-bearer of Joab (2 Sam. 23:37; 1 Chron. 11:39), the commander of David’s army.

Nahash (1) The Ammonite king who attacked the Israelite city of Jabesh Gilead early in Saul’s reign and was subsequently defeated by the new Israelite king (1 Sam. 11). Nahash (lit., “snake”) advanced against Jabesh Gilead and demanded to humiliate Israel by gouging out the right eye of everyone in the city as a condition to end the siege. A copy of 1 Samuel from Qumran includes additional material also found in Josephus’s Antiquities. These versions also state that Nahash had already gouged out the right eye of all the Israelites in the region except for the seven thousand men in Jabesh Gilead. Fortunately for them, as all versions attest, Saul responded by raising an army and defeating Nahash and the Ammonites. The Nahash who is in league with David in later texts (2 Sam. 10:2; 17:27) may well be the same king. (2) The father of Abigal and Zeruiah (2 Sam. 17:25), (half-?)sisters to David (1 Chron. 2:13–16). Apparently, he died, and his widow married David’s father, Jesse.

Nahath (1) A descendant of Esau through Reuel (Gen. 36:13; 1 Chron. 1:37). One of the clans of the Edomites derives its name from this Nahath (Gen. 36:17). (2) A Levite in the genealogy in 1 Chron. 6:26. He may be the same person as Toah (1 Chron. 6:34) and Tohu (1 Sam. 1:1). (3) A Levite overseer in the time of Hezekiah (2 Chron. 31:13).

Nahbi A spy from the tribe of Naphtali, one of twelve sent by Moses to reconnoiter the promised land (Num. 13:14).

Nahor (1) A descendant of Shem, he was the son of Serug, father of Terah, and grandfather of Abraham (Gen. 11:22–25). (2) The son of Terah and the brother of Abraham and Haran (Gen. 11:26). Nahor married Milkah, the daughter of his deceased brother, Haran (Gen. 11:28–32). When Abraham headed west for the land of Canaan (Gen. 12:1, 4), Nahor remained in the city of Harran. Through his wife, Milkah, Nahor fathered eight sons, and he fathered another four through his concubine, Reumah (Gen. 22:20–24). Bethuel, one of Nahor’s sons through Milkah, fathered Rebekah, who became the wife of Isaac, Abraham’s son (Gen. 24:15, 67). Relations between Nahor’s eastern branch of the family and Abraham’s western branch apparently ceased when Laban, Nahor’s grandson, had a falling out with Jacob, Abraham’s grandson, in which Laban called on the Lord (Abraham’s God) and on Nahor’s god to judge between the two parties (Gen. 31:53). (3) “The town of Nahor” is a town in northwest Mesopotamia, where Abraham’s servant encounters Rebekah at the well (Gen. 24:10). “Nahor” may be the name of the town, or the text is simply referring to the town where Nahor once lived (so GNT, NLT).

Nahshon The son of Amminadab, the father of Salmon, and an ancestor of David and Jesus (Ruth 4:20; 1 Chron. 2:10–11; Matt. 1:4; Luke 3:32). He was a tribal leader for Judah in the exodus (Num. 2:3; 7:12–17; 10:14), a brother-in-law to Aaron (Exod. 6:23 [KJV: “Naashon”]), and an assistant in the census conducted by Moses and Aaron (Num. 1:7).

Nahum, Book of The seventh of the Minor Prophets, Nahum is striking for its powerful poetry and its hard-hitting message. The prophet glories in God’s coming judgment on Assyria. After all, Assyria’s downfall will bring relief for Judah. Nahum’s focus on divine judgment on Assyria has raised the question of its continuing relevance for modern readers (see “New Testament Connections” below).

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Nahum, like many prophetic books, opens with a superscription that includes an authorship attribution: “The book of the vision of Nahum the Elkoshite” (1:1b). Unfortunately, Nahum is unknown elsewhere in the Bible. Indeed, his hometown of Elkosh is not located with certainty and has been associated with sites in Mesopotamia near Nineveh, northern Israel, and Judah. The name “Nahum” in Hebrew means “compassion.” Although his words carry little compassion on the surface, his excitement about Assyria’s future defeat stems from the compassion that he feels for his own people.

Although little can be said about Nahum the person, more is known about the period in which he received his vision. The prophecy foresees the downfall of Assyria, in particular the city of Nineveh. Since Nineveh fell in 612 BC, the vision must be dated before that time. On the other side, 3:8–10 looks back on the fall of the Egyptian city of Thebes, which fell to the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal in 664 BC. Thus, the book comes from the time between 664 and 612 BC. If 1:12 is read as indicating that Assyria has not yet visibly weakened, then the book should be dated before 630 BC.

ANCIENT NEAR EASTERN HISTORICAL CONTEXT

The book speaks to events in the seventh century BC. Since at least the mid-eighth century BC, Assyria had been the dominant power in the Near East. Under the effective military leadership of Tiglath-pileser III (r. 744–727 BC), Shalmaneser V (r. 726–722), and Sargon II (r. 721–705 BC), the Assyrians incorporated Syria and the northern kingdom of Israel into their empire and subjected Judah to tribute payments. This policy continued under Sennacherib (r. 704–681 BC), Esarhaddon (r. 680–669 BC), and Ashurbanipal (r. 668–627). However, Ashurbanipal, though starting in a powerful position, found the empire beginning to weaken toward the end of his reign. It was likely during Ashurbanipal’s reign that Nahum wrote concerning Nineveh’s fall.

The fulfillment of this expectation came in the form of a resurgent Babylon under the leadership of Nabopolassar, a Chaldean chief who assumed the kingship of Babylon. He began his insurgency in 626 BC, but it was not until 612 BC that he, with the strong support of the Medes, took the city of Nineveh. A small contingent of Assyrians survived and tried to regroup in Harran, but they were completely defeated in 609 BC at Carchemish, despite help from Pharaoh Necho of Egypt.

An Assyrian relief depicting the siege of Lachish. Nahum predicts judgment against Assyria for its destruction of Israel.

LITERARY CONSIDERATIONS

The superscription uses three terms that help describe the genre: “book,” “vision,” and “oracle.” That the prophecy is a “book” points to the literary rather than oral origins of the work. While many prophetic books begin as sermons, Nahum has all the earmarks of a literary composition. That the prophecy is a “vision” not only underlines the future orientation of its message but also highlights the use of the event-vision form that talks about future events as if they are happening in the present (e.g., 2:3–10). The word translated “oracle” also points to the book’s future orientation. Since it occurs elsewhere as well as here in contexts that envision God’s actions as a warrior against foreign nations, the word may more precisely point to the book’s character as a “war oracle” or “oracle against a foreign nation.”

OUTLINE

I. Superscription (1:1)

II. Hymn to God the Divine Warrior (1:2–8)

III. The Divine Warrior Judges and Saves His People (1:9–2:2)

IV. The Vision of the Fall of Nineveh (2:3–10)

V. The Lion Taunt (2:11–13)

VI. Woe-Oracle against Nineveh (3:1–3)

VII. The Sorceress-Harlot Taunt (3:4–7)

VIII. Historical Taunt against Nineveh (3:8–10)

IX. Further Insults against Nineveh (3:11–15c)

X. Locust Taunt (3:15d–17)

XI. Concluding Dirge (3:18–19)

THEOLOGICAL MESSAGE

Nahum prophetically anticipates the fall of Nineveh. Historically, the city was defeated by a coalition of Babylonians and Medes. Nahum, however, understands that the real cause of Nineveh’s demise and Judah’s relief is none other than God. The book begins with a hymn that praises God as warrior who “takes vengeance on his foes” (1:2–8). The remainder of the book specifies that the warrior is coming against Nineveh.

NEW TESTAMENT CONNECTIONS

Nahum is never directly cited in the NT. Indeed, at first it may be hard to see the relevance of a book that is concerned with the fall of an ancient city. However, the NT also describes God as a warrior who fights against the forces of evil. Jesus Christ takes the battle against the “powers and authorities,” spiritual enemies. He wins this battle by dying on the cross (for an example of a text that uses military language in reference to the death of Christ, see Col. 2:13–15). Furthermore, the apocalyptic texts of the NT (see Rev. 19:11–21) anticipate the return of Christ as a warrior who will bring all evil to an end. The book of Nahum is a witness to God’s warfare against evil, which continues to the final victory at the end of the ages.

Nail Several different Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek biblical words are translated into English as “nail.” First, there are the common fasteners that attach one item to another (Jer. 10:4), often made of iron to join pieces of wood (1 Chron. 22:3; Isa. 41:7), or even made of gold to overlay sheets of gold (2 Chron. 3:9). The writer of Ecclesiastes speaks metaphorically of wise sayings as “firmly embedded nails” (Eccles. 12:11). Roman soldiers fastened Jesus to the cross with nails (John 20:25). Second, there are pegs either driven into walls from which people hung items (Isa. 22:25; Ezek. 15:3) or used to anchor tents (Isa. 33:20). The tent pegs for the tabernacle were made of bronze (Exod. 27:19), and Jael used a tent peg to kill Sisera (Judg. 4:21–22). Isaiah speaks metaphorically of Eliakim as one whom God will drive “like a peg into a firm place” (Isa. 22:23). Finally, there are the nails of fingers (Dan. 4:33). Deuteronomy prescribes the trimming of nails as part of the purification process for Israelite men to marry captive women (Deut. 21:12).

Nain Just north of Mount Moreh lies Nain; to the southwest was Shunem. When Jesus brought a widow’s son back to life, the crowd declared that a prophet had arisen (Luke 7:11–17), remembering Elisha’s restoration of the Shunammite woman’s son (2 Kings 4).

Naioth A site in or near Ramah in the central hill country of Benjamin. The prophet Samuel lived in Ramah, approximately six miles north of Jerusalem. Samuel and David fled from Saul to “Naioth at Ramah,” perhaps a section of the town or a house of instruction in Ramah, or even a shepherds’ camp nearby where Samuel supervised a prophetic community (1 Sam. 19:18–20:1).

Naked Refers to genitals and buttocks (Nah. 3:5) and, since Adam’s sin, is synonymous with shame. The image of God, originally created good, was damaged by sin and death.

Nakon Located between Baalah of Judah (Kiriath Jearim) and Jerusalem, the “threshing floor of Nakon” is mentioned in the account of David’s transport of the ark of the covenant to Jerusalem (2 Sam. 6:6). Here Uzzah reached out his hand to steady the ark and was struck dead by God for his irreverence. “Nakon” may be a place name or the name of the owner of the threshing floor. It is identified as the threshing floor of Kidon in the parallel account in Chronicles (1 Chron. 13:9).

Names of God The names of God given in the Bible are an important means of revelation about his character and works. The names come from three sources: God himself, those who encounter him in the biblical record, and the biblical writers. This article is concerned mainly with the names that occur in the OT, though the NT will be referenced when helpful.

In the Bible the meaning of names is often significant and points to the character of the person so named. As might be expected, this is especially true for God. The names that he gives to himself always are a form of revelation; the names that humans give to God often are a form of testimony.

YAHWEH: THE LORD

Pronunciation. Unquestionably, for OT revelation the most important name is “(the) LORD.” In English Bibles this represents the name declared by God to Moses at the burning bush (“I AM WHO I AM” [Exod. 3:13–15]) and the related term used elsewhere in the OT; in Hebrew this term consists of the four consonants YHWH and is therefore known as the Tetragrammaton (“four letters”). Hebrew does not count vowels as part of its alphabet; in biblical times one simply wrote the consonants of a word and the reader supplied the correct vowels by knowing the vocabulary, grammar, and context. However, to avoid violating the commandment in the Decalogue that prohibits the misuse of God’s name (Exod. 20:7; Deut. 5:11), the Jews stopped pronouncing it. Consequently, no one today knows its correct original pronunciation, but the best evidence available suggests “Yahweh,” which has become the conventional pronunciation (consider the Hebrew word “hallelujah,” which actually is “hallelu-Yah,” hence “praise the LORD”). In ancient Jewish tradition, “Adonai” (“my Lord”) was substituted for “Yahweh.” In fact, when Hebrew eventually developed a vowel notation system, instead of the vowels for “Yahweh,” the vowels for “Adonai” were indicated whenever YHWH appeared in the biblical text, as a reminder. Combining the consonants YHWH with the vowels of “Adonai” yields something like “Yehowah,” which is the origin of the familiar (but mistaken and nonexistent) “Jehovah.” English Bibles typically use “LORD” (small capital letters) for “Yahweh,” and “Lord” (regular letters) for “Adonai,” which distinguishes the two.

Meaning. More vital than the matter of the pronunciation of YHWH is the question of its meaning. There seem to be two main opinions. One sees YHWH as denoting eternal self-existence, partly because it is suggested by the grammar of Exod. 3:14 (the words “I am” use a form of the Hebrew verb that suggests being without beginning or end) and partly because that is the meaning Jesus apparently ascribes to it in John 8:58. The other opinion, suggested by usage, is that YHWH indicates dynamic, active, divine presence: God’s being present in a special way to act on someone’s behalf (e.g., Gen. 26:28; 39:2–3; Josh. 6:27; 1 Sam. 18:12–14). This idea also appears in the episode of the burning bush (Exod. 3:12): when Moses protests his inadequacy to confront Pharaoh, God assures him of his presence, a reality noted with other prophets (1 Sam. 3:19; Jer. 1:8).

Perhaps the best points of reference for understanding the meaning of YHWH are God’s own proclamations. In addition to Exod. 3:13–15, at least two other passages in Exodus give God’s commentary (as it were) about the meaning of his name. An important one is Exod. 34:5–7. A key passage in the theology proper of ancient Israel, its themes echo in later OT Scripture (Num. 14:18–19; Ps. 103:7–12; Jon. 4:2). What is noteworthy about the texts cited is that all of them say something remarkable about the grace of God. This fits, for the revelation of Exod. 34:5–7 is given in the context of covenant renewal after the incident of the golden calf. Moses invokes God’s name in the Numbers text to avoid catastrophic judgment when the Israelites refuse to enter the promised land. The psalm text picks up this theme and connects it with God’s revelation of his ways to the chosen people. Jonah, remarkably, affirms that the same grace extends even toward a wicked Gentile city such as Nineveh.

Another such passage is Exod. 6:2–8. Here God reaffirms his redemptive purpose for captive Israel, despite the fact that Moses’ first encounter with Pharaoh has not gone well. God assures the prophet that he has remembered his covenant with the patriarchs, whom he says did not know him as “Yahweh,” which probably means that the patriarchs did not experience him in the way or character that their descendants would in the exodus event (though it is possible to translate the Hebrew here as a rhetorical question with an affirmative idea: “And indeed, by my name Yahweh did I not make myself known to them?”). God then proceeds to outline the redemptive experience in its fullness: deliverance from bondage, reception into a covenant relationship, and possession of the land promised to their ancestors (vv. 6–8). The statement is bracketed with this declaration: “I am the LORD” (vv. 2, 8). One stated purpose of this redemptive work is that Israel might come to understand this (v. 7). This is important to note because a central theme of Exodus as a book is the identity of the God of Israel. This concern prompts Moses to ask for God’s name at the burning bush (3:13), and this contempt for the God of the enslaved Hebrews causes Pharaoh to be dismissive at his first meeting with Moses and Aaron (5:2). Moses asks with the concern of a seeker and receives one of the most profound declarations of God’s identity in the Bible. Pharaoh asks with the contempt of a scorner and receives one of the most powerful displays of God’s identity in the Bible (the plagues). The contrast is both striking and instructive. The meaning of God’s name, then, is revealed in works as well as words, and his purpose is that not just his people but all peoples may come to understand who he is. Yet another majestic statement in the book of Exodus (9:13–16) makes this abundantly clear.

Based on this pattern of usage, the name “Yahweh” seems to signify especially the active presence of God to bless, deliver, or otherwise aid his people. Where this presence is absent, there is no success, victory, protection, or peace (Num. 14:39–45; Josh. 7:10–12; Judg. 16:20; 1 Sam. 16:13–14). The message that God not only is but also is present to save and deliver may well be the most important truth communicated in the OT, and it is only natural to see its ultimate embodiment in the person and work of Christ (Isa. 7:14; cf. Matt. 1:21–23).

Name used in combination. The name “Yahweh” also is used in combination with other terms. After God grants a military victory to Israel over the Amalekites, Moses names a commemorative altar “Yahweh Nissi,” meaning “the LORD is my Banner” (Exod. 17:15). In Ezekiel’s temple vision Jerusalem is called “Yahweh Shammah,” meaning “THE LORD IS THERE” (Ezek. 48:35). A familiar expression is “the LORD of hosts,” which is generally comparable to the expression “commander in chief” used in American culture (cf. 1 Kings 22:19–23).

ELOHIM

This is the first term for God encountered in the Bible, right in the opening verse. It is a more generic term, denoting deity in contrast to humans or angels. “Elohim” is a plural form; the singular terms “El” and “Eloah” are used occasionally, particularly in poetic texts. “El” is a common term in the biblical world; in fact, it is the name for the father of Baal in the Canaanite religion. This may explain why the Bible commonly uses the plural form, to distinguish the one true God, the God of Israel, from his pagan rivals. Others explain the plural form as a “plural of majesty” or “plural of intensity,” though it is uncertain just what this would mean. Some see the foundation for NT revelation of the Trinity (Gen. 1:26–27; 11:6–7; cf. John 17:20–22), but this is unlikely. The plural form also can serve simply as a common noun, referring to pagan deities (Exod. 12:12), angels (Ps. 97:7, arguably), or even human authorities (Exod. 22:28, possibly).

“El” also occurs in combination with other descriptive terms. The best known is “El Shaddai,” meaning “God Almighty” (Gen. 17:1). The precise meaning of “Shaddai” is uncertain, but it seems to have the notion of “great/powerful one.” The distressed Hagar, caught, comforted, and counseled by the mysterious personage at a well, calls God “El Roi,” which means “the God who sees me” (Gen. 16:13). One of the most exalted expressions to describe God is “El Elyon,” meaning “God Most High.” This title seems to have particular reference to God as the owner and master of creation (Gen. 14:18–20).

ADONAI

As noted above, this common word meaning simply “(my) lord/master” is used regularly in place of the personal name of God revealed to Moses in Exod. 3:14. And in the OT of most English Bibles this is indicated by printing “Lord” as opposed to “LORD” (using small capital letters). However, “Adonai” is used of God in some noteworthy instances, such as Isaiah’s lofty vision of God exalted in Isa. 6 and the prophecy of Immanuel in Isa. 7:14. In time, this became the preferred term for referring to God, and the LXX reflected this by using the Greek word kyrios (“lord”) for Yahweh. This makes the ease with which NT writers transfer the use of the term to Jesus (e.g., 1 Cor. 12:3) a strong indication of their Christology.

Naming The act of giving a specific term of identification to someone or something. Naming is a notable feature of biblical narrative. From the beginning, God orders and structures creation by naming the things that he makes, from the elements of nature to humankind (Gen. 1:5, 10; 5:2). As his ruling representative, Adam is granted the privilege of naming the animals (1:27–28; 2:19–20). He later names his wife, both as a being and as a person (2:23; 3:20). Eve, in turn, names Seth after losing Abel to the murderous rage of his brother Cain (4:25). With the naming of people, what is notable is that in each case the name clearly is chosen for a reason: the name has significance for the person, revealing something significant about character, role, or destiny.

The patriarchal narratives of Genesis are notable in this regard. In Gen. 17 both Abram and Sarai receive name changes, to the more familiar “Abraham” and “Sarah.” No particular explanation is given in her case, but “Abraham” is explained in terms of God’s promise of numerous descendants, “father of many” (17:5). Later in the conversation, God decrees that the name of the promised son will be “Isaac.” The name means “he laughs,” and it is chosen initially in response to Abraham’s laughter at the idea of having a son in his old age (17:17, 19). When Isaac is born, Sarah describes it as the laughter of joyful surprise (21:6–7). But when Ishmael engages in some less innocent “laughing” about Isaac, it becomes the occasion of Ishmael’s expulsion along with his mother (21:8–14). In the next generation, Esau is named for his red, hairy appearance—something that will be important on a later occasion (25:25; 27:5–23). His twin brother’s name is both more symbolic and more suggestive of character, as Esau himself acknowledges (25:26; 27:34–36).

The NT also has its cases of notable naming. The apostles express appreciation for the edifying spirit of a believer named “Joseph” by calling him “Barnabas,” which means “son of encouragement” (Acts 4:36). Likewise, Jesus marks Simon’s recognition of his identity by naming him “Peter” (Aram. Cepha; Gk. Petros—both mean “rock”). Jesus himself is the supreme example of having been given a meaningful name (Matt. 1:20–21), though it should be noted that his Hebrew name, “Joshua” (yehoshua’, “Yahweh saves/is salvation”), was common in Jewish culture. This is why others usually referred to him by some descriptive phrase, such as “Jesus of Nazareth” or “Jesus, who is called Messiah.”

Places also receive names, often as a result of some encounter with God. Jacob gives the name “Bethel” to the spot where God first spoke with him (Gen. 28:16–19). The names that Moses gives to some locations of the wilderness journey are tragically indicative of Israel’s frequent disobedience during that time (Exod. 17:1–17; Num. 11:3–5, 18–20, 31–34).

Naomi A woman of Judah whose family fortunes are the focus of the book of Ruth. Her name means “pleasant,” though when her circumstances turned difficult, she asked to be called Mara (“bitter”) instead. When her family lived in Moab for a time to escape a famine, she eventually became the mother-in-law of Ruth. She and Ruth returned to her hometown of Bethlehem after the deaths of her husband and sons. Naomi arranged for Ruth’s eventual marriage to Boaz, which provided redemption for her family property.

Naphath-dor See Naphoth Dor.

Naphish A descendant of Ishmael, Abraham’s son through Hagar. He is listed in the genealogies of Gen. 25:15; 1 Chron. 1:31. His descendants were defeated by the eastern Israelite tribes prior to the conquest (1 Chron. 5:19).

Naphoth Dor This expression means “hills or heights of Dor.” It occurs in Josh. 11:2; 12:23; 1 Kings 4:11. Dor was an important city on the northern coastline of Israel, about fifty miles southwest of Hazor and just south of the Phoenician border. It fell within the tribal territory of western Manasseh (Josh. 17:11).

Naphtali The fourth son of Israel (Jacob) and the progenitor of the tribe that bears his name. He was the second surrogate son of Rachel through her maidservant Bilhah (Gen. 30:7–8).

Naphtali, Tribe of The tribe descended from Naphtali, son of Jacob and Bilhah. This tribe settled in northern Israel, east of Asher and south of Dan, not far from the Sea of Kinnereth (Sea of Galilee). It is noted that, like other tribes, it failed to completely drive out the Canaanites in its designated territory, which contributed to the difficulties that the nation experienced after the passing of Joshua’s generation (Judg. 1:33). Naphtali has a quiet history in Scripture but is mentioned in the prophecy of Isa. 9:1–7, which Matthew cites in connection with Jesus’ ministry in Galilee (Matt. 4:12–17). Ezekiel also describes an assigned land area for Naphtali in his temple vision (Ezek. 48:3–4).

Naphtuhites Descendants of Ham mentioned twice in the Bible, both in genealogies (Gen. 10:13; 1 Chron. 1:11). They are traced from Ham through “Mizraim,” which is the Hebrew word for “Egypt.” This seems to suggest an origin in northern Egypt (the Nile Delta). “Naphtuhite” may contain the name of the Egyptian god Ptah, whose sacred city was Memphis, in the Nile Delta area.

Narcissus The believers within the household of Narcissus are mentioned in Paul’s greetings in Rom. 16:11. The phrase “those in the household of Narcissus” refers to the slaves and freedmen or freedwomen of Narcissus, while the phrase “in the Lord” specifies those of them who were Christians. The servants of Narcissus’s household who became Christians formed a house church in Rome. Other house churches mentioned by Paul in these closing greetings include that of Priscilla and Aquila. Paul does not specify whether Narcissus himself was a Christian.

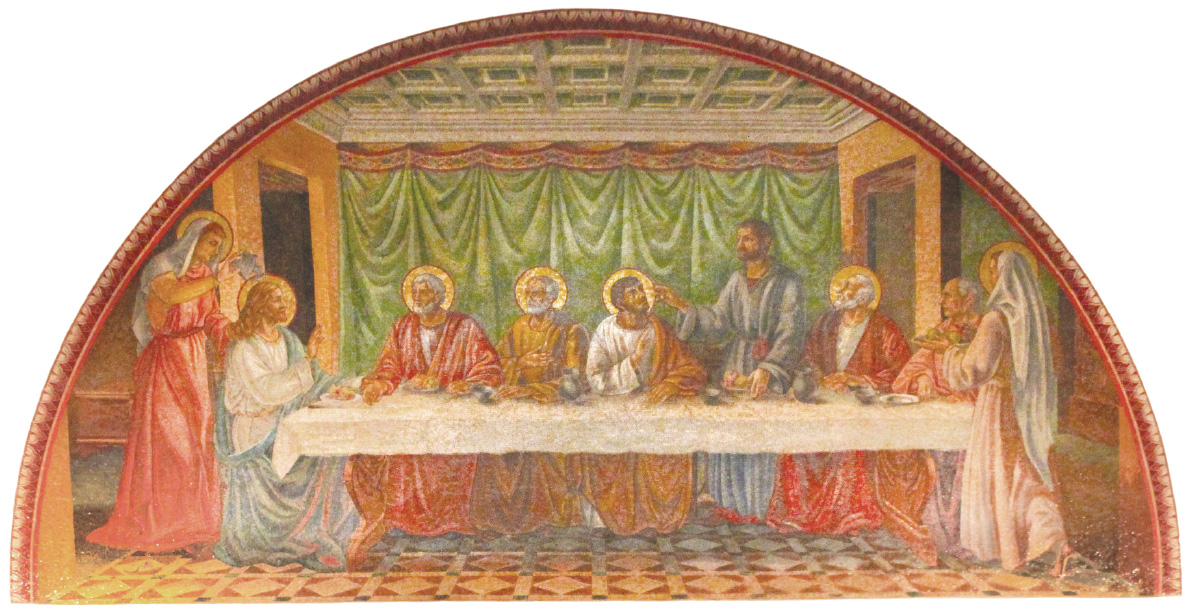

Nard A high-quality and fragrant ointment or perfume, also known as spikenard. Song of Songs includes nard among fragrant items used metaphorically by the lover to describe his beloved (Song 4:13–14). Mark 14:3 and John 12:3 refer to the same incident, the anointing of Jesus at Bethany a few days before the crucifixion, and emphasize the high monetary value of the nard.

Mosaic depicting the anointing of Jesus with nard, at the Church of Saint Lazarus in Bethany

Nathan (1) The prophet Nathan was consulted by David when he contemplated building a temple to house the ark (2 Sam. 7). Without consulting God, Nathan encouraged David in this laudable project, suggesting that in the prophet’s mind the project was so obviously right (acknowledging as it did God’s supreme kingship over the nation) that there was no need to ask God. However, an unexpected divine refusal came that same night. A divine speech, long by biblical narrative standards (twelve verses), was required to explain the baffling divine refusal. The problem with the project was that the time was not ripe (2 Sam. 7:11; cf. 7:1), for David still had battles to fight.

Nathan reappears in biblical narrative in 2 Sam. 12, sent by God to rebuke David for taking Bathsheba (this confrontation is alluded to in the superscription of Ps. 51). These interventions of Nathan came at David’s high point and low point. Nathan’s parable about the “little ewe lamb” caused David to incriminate himself and pronounce his own sentence. David, on his immediate repentance, was forgiven (v. 13), but the rest of his reign was the working out of the punishment pronounced by Nathan: “The sword will never depart from your house” (v. 10). Nathan predicted the death of the son born from the illicit union (v. 14). Later, God sent word through Nathan that a second son, Solomon, was to be named “Jedidiah” (“loved by the LORD”) (v. 25; see NIV footnote). Nathan, in collusion with Bathsheba, took Solomon’s part in the competition for the throne (1 Kings 1). Nathan and the priest Zadok anointed Solomon king at Gihon (1 Kings 1:45). He also had a role in David’s ordering of the Levites (2 Chron. 29:25). Nathan is the reputed author of a book of chronicles about David’s reign (1 Chron. 29:29) and a history about Solomon’s (2 Chron. 9:29).

Presumably, the Nathan of 1 Kings 4:5 is the prophet, whose son Azariah was in charge of Solomon’s district officers. Zabud, another son, was a priest (here this refers to a chief officer) and personal adviser (cf. Hushai’s role in 2 Sam. 15:37) under Solomon. There is mention of “the house of Nathan” as still prominent in the postexilic period (Zech. 12:12).

(2) A son of David, born in Jerusalem (2 Sam. 5:14; 1 Chron. 3:5; 14:4), he is in the genealogy of Jesus (Luke 3:31). (3) The father of Igal, one of David’s thirty mighty warriors (2 Sam. 23:36). (4) A Judahite, the son of Attai and father of Zabad (1 Chron. 2:36). (5) The brother of Joel, one of David’s mighty warriors (1 Chron. 11:38). (6) One of the leaders enlisted by Ezra to seek Levites willing to return to Jerusalem (Ezra 8:16). (7) One of the men who were guilty of taking a foreign wife during the time of Ezra (Ezra 10:39).

Nathanael One of Jesus’ disciples, mentioned by name only in John 1:45–49; 21:2. He was from Cana in Galilee (21:2), where Jesus changed water into wine. Nathanael was initially skeptical of Philip’s claims about Jesus because Jesus was from Nazareth (1:45–46), but his skepticism turned to belief when Jesus, who called Nathanael “truly . . . an Israelite in whom there is no deceit,” demonstrated miraculous knowledge of where Nathanael had been sitting before he met Jesus (1:47–49). Nathanael quickly declared his faith in Jesus. As a result of Nathanael’s ready faith, Jesus promised him that he would be witness to Jesus’ salvific work and the miraculous transformation of the broken relationship between God and humankind (John 1:50). Nathanael was one of the first disciples to see the risen Jesus (John 21:1–4).

Nathanael was most likely the same person as Bartholomew (Matt. 10:3; Mark 3:18; Luke 6:14; Acts 1:13), given that John never mentions Bartholomew and the Synoptic Gospels never mention Nathanael, and that the Synoptic Gospels list Bartholomew’s name directly after Philip’s, while John connects Nathanael and Philip in his narrative.

Nathan-Melech See Nathan-Melek.

Nathan-Melek An official who lived in the Jerusalem temple and whose room was in close proximity to an object used for sun worship. King Josiah removed it from the temple during his reformation (2 Kings 23:11).

Nations See Gentiles.

Native(s) As an adjective, “native” refers to being born or originating in a particular place (Gen. 24:7; 31:13; Num. 22:5). As a noun, it refers to those who were born in or are original inhabitants of a particular place. Several Bible versions refer to local people of Malta, where Paul stops on his journey to Rome, as “natives” (Acts 28:4 NASB, RSV, NRSV, NAB [Gk. barbaroi, meaning “barbarians, foreigners”]). Other versions use “islanders” (NIV), “local people” (HCSB), or “people of the island” (NLT).

Nativity of Christ See Jesus Christ.

Natural When God completed his work at creation, all that he made he pronounced “very good” (Gen. 1:31). The world was functioning harmoniously, and most important, the humans God had created in his own image lived in a sinless relationship with him. In one sense this universe before the fall represents its “natural” state. Evil and suffering enter the creation as fundamentally alien elements. However, through Adam and Eve’s disobedience (Gen. 3) what was unnatural has become natural. “Sin entered the world through one man, and death through sin, and in this way death came to all people, because all sinned” (Rom. 5:12). For this reason, God sent his Son to die on a cross and rise again, to redeem his people from their unnatural (against God’s revealed will [cf. Rom. 1:20–27]) yet natural (inborn and pervasive [cf. Rom. 6:19]) state of sinfulness.

Naum In Luke 3:25 the KJV rendering of the Greek name for Nahum (Naoum), an ancestor of Jesus.

Nave Most commonly, the long central hall of a cross-shaped church where the congregation sits. Some Bible versions use the term to refer to the central hall of the Jerusalem temple between the vestibule and the most holy place (1 Kings 6:3, 5, 17, 33; 7:21; Ezek. 41:1–2 RSV, NASB, NRSV, NAB). The NIV has “main hall” in most of these passages. The KJV uses the word “naves” in 1 Kings 7:33 in an archaic sense, referring to the “rims” (NIV) of a wheel.

Navel One particular Hebrew word for “navel,” shor, occurs three times in the OT. In Song 7:2 the male character lists his lover’s navel among the physical attributes that he praises. In Prov. 3:8 shor (NIV: “body”) is probably used figuratively to refer to the body receiving nourishment. In Ezek. 16:4 shor is used to refer to the umbilical cord (NRSV: “navel cord”).

Another Hebrew word, tabbur, occurring in Ezek. 38:12 (also Judg. 9:37) and translated “center” in the NIV, might best be translated as “navel,” thus connecting to an ancient Near Eastern tradition that views the mountain where a deity dwells as the “navel” or nexus between heaven and earth. In this verse, then, Mount Zion in Jerusalem, where God dwelt among his people, would be referred to as the “navel of the earth.”

Navy See Fleet; Ships, Sailors, and Navigation.

Nazareth, Nazarene In the first century, Nazareth was a small village in the extreme southerly part of lower Galilee, midway between the Sea of Galilee and the Mediterranean Sea. It was near Gath Hepher, the birthplace of Jonah the prophet to the Gentiles (2 Kings 14:25), and Sepphoris, one of the three largest cities in the region. Not far was the Via Maris, the great highway joining Mesopotamia to Egypt and ultimately the trading network that linked India, China, central Asia, the Near East, and the Mediterranean. The village was perched 1,150 feet above sea level, overlooking the Jezreel Valley, with several terraces for agriculture cut into the mountain. A Nazarene could look south across the grand Plain of Esdraelon, west to Mount Carmel on the Mediterranean coast, east to nearby Mount Tabor, and north to snowcapped Mount Hermon. The community, whose population may have averaged around five hundred, subsisted from agriculture. Capital resources included almonds, pomegranates, dates, oil, and wine. (Excavations have located vaulted cells for wine and oil storage, as well as wine presses and storage jar vessels.) Nazareth appears to have been uninhabited from the eighth to the second centuries BC, until it was resettled during the reign of John Hyrcanus (134–104 BC), probably by a Davidic clan of army veterans. The claim that Jesus’ adoptive father, Joseph, was a descendant of David and a resident of Nazareth is therefore plausible (Matt. 1:20; Luke 2:4–5). Today, Nazareth is the largest Arab city in Israel.

Although Jesus’ ministry was unsuccessful in Nazareth, he and his followers were called “Nazarenes” (Mark 1:24; 10:47; John 18:5, 7; Acts 2:22; 3:6; 24:5). Descendants of Jesus’ family continued to live in the area for centuries. The epithet “Nazarene” probably was intended as a slur. Nathanael is unimpressed by Jesus’ origin in Nazareth (John 1:46). The village is not mentioned in the OT. Some even doubted its existence, until 1962, when the place name “Nazareth” was discovered on a synagogue inscription in Caesarea Maritima.

Nazirite Both men and women could take the Nazirite vow (Num. 6:1–21), consecrating themselves to God and abstaining from all grapevine products, avoiding contact with corpses, and allowing their hair to grow long. The first two stipulations mandate separation from conditions reflective of decay and corruption, clearly an affront to God’s holiness (cf. Amos 2:11–12). Long hair was the sign of the vow, symbolic of the power of God (Judg. 16:17).

Inadvertently touching a corpse interrupted the vow. Rededication necessitated shaving the head and sacrificing sin and burnt offerings, along with a guilt offering for having defiled something holy (Lev. 5:14–19). The vow could last one’s entire life, as was intended for Samson (Judg. 13:7) and Samuel (1 Sam. 1:11), or it could simply be for a period of time (Acts 18:18; 21:24). In the latter case, the vow was terminated with the presentation of sin, burnt, and fellowship offerings and shaving and burning the hair at the tabernacle.

An individual could take the vow by personal volition, or it could be imposed by others. Most of the biblical examples fall into the latter category. The angel of the Lord declared that Samson would be a Nazirite for his entire life, although Samson despised the sanctity of the vow in just about every way (Judg. 13–16). Hannah dedicated Samuel for his life (1 Sam. 1:11). John the Baptist was also apparently given over to these conditions by the word of the angel Gabriel (Luke 1:15).

Neah A town within the tribal boundaries of Zebulun (Josh. 19:13).

Neapolis The harbor town for the larger city of Philippi, on the Aegean coast. Paul, after receiving a vision, set out with his companions to Macedonia. During the journey, they passed through Neapolis (Acts 16:11) before traveling approximately ten miles on to Philippi. Their arrival in Neapolis marks Paul’s first entry into Europe.

Neariah (1) A leader of the tribe of Simeon during the reign of Hezekiah who helped drive the remaining Amalekites from Mount Seir (1 Chron. 4:42). (2) One of the four sons of Shemaiah, a descendant of David (1 Chron. 3:22).

Nebai One of the leaders who sealed the covenant with God following Ezra’s public reading of the law (Neh. 10:19).

Nebaioth (1) The name of the firstborn son of Ishmael (Gen. 25:13; 28:9; 36:3; 1 Chron. 1:29) and an Arabic tribe mentioned in cuneiform sources. (2) The place from where rams will be gathered, mentioned in the context of future blessing for Jerusalem (Isa. 60:7).

Nebajoth See Nebaioth.

Neballat A town at the western end of the hill country of Ephraim that members of the tribe of Benjamin repopulated after the Babylonian exile (Neh. 11:34). The site is apparently identified with Beit Nabala (Horvat Nevallat), located approximately twenty-two miles northwest of Jerusalem and four miles northeast of Lod, near the edge of the coastal plain.

Nebat The father of Jeroboam, the first king of the northern kingdom of Israel. His name appears only in the phrase “Jeroboam son of Nebat” and serves to distinguish him from Jeroboam II.

Nebo (1) Mount Nebo is located in Abarim, a mountain range in northwest Moab separating the Transjordan Plain from the Jordan Valley. Nebo is usually identified with a mountain of the same modern name that is five miles northwest of Madaba and is well over four thousand feet in elevation. This was the mountain that God commanded Moses to ascend to get a glimpse of the promised land before he died (Deut. 32:48–52; 34:1). On a clear day, it offers a spectacular view. In the period right after the entry into the land, the area was controlled by the Reubenites (Num. 32:3, 38). Later, it is mentioned as a prominent location in the land of Moab (Jer. 48:1, 22). (See also Abarim.) (2) The god Nebo was considered the son of the Babylonian chief god, Marduk, and was himself the god of wisdom and writing. He was thus the patron god of scribes (Isa. 46:1). (3) Nebo is listed as an ancestor of seven men who had married foreign women during the postexilic period (Ezra 10:43). (4) The hometown of fifty-two men returned from the Babylonian exile (Ezra 2:29).

Nebo-Sarsekim A Babylonian official identified in Jer. 39:3. The division and significance of the names in the list is disputed. Some versions treat “Nebo” (Heb. nebu) as the second half of Samgar’s name, and read this part of the list as “Nergal-sharezer, Samgar-nebo, Sarsechim the Rab-saris” (NRSV, HCSB; similarly, NASB). The NIV and others (see NLT, REB, NET) instead read the Hebrew as two names, with a place name and a title: “Nergal-Sharezer of Samgar, Nebo-Sarsekim a chief officer.”

Nebuchadnezzar The king of Babylon from 605 to 562 BC. Information about his life and reign comes from the Bible as well as ancient Babylonian sources. Nebuchadnezzar had many military and political accomplishments. The following material focuses mainly on those that illumine the biblical text.

Nebuchadnezzar’s father, Nabopolassar, was a Chaldean (Aramaic-speaking) tribal chief from the extreme south of Babylon (near what is today the Persian Gulf). In 626 BC he rebelled against Assyria, which for many years had subjugated Babylon to vassal status. In 612 BC the Babylonians, along with the Medes, defeated the Assyrian capital, Nineveh. Remnants of the Assyrian army fled to the region around Harran in northern Syria under the leadership of Ashur-uballit. In 609 BC Pharaoh Necho of Egypt attempted to bolster the Assyrian army, but the Babylonians soundly defeated them at the battle of Carchemish. At this point, Babylon inherited what was the Assyrian Empire, which included Syria and the northern kingdom of Israel. In 605 BC Nabopolassar died of natural causes, and his son Nebuchadnezzar succeeded him as king.

In the same year, according to Dan. 1:1–3, Nebuchadnezzar “besieged” Jerusalem. The Hebrew verb (tsur) could indicate a military siege or simply a diplomatic coercion. In any case, the pro-Egyptian Judean king, Jehoiakim, had no recourse but to submit, turning over to the Babylonian king the temple vessels and also political hostages from the royal family, including Daniel and his three friends.

A cylindrical inscription of Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon (605–560 BC)

In 597 BC Jehoiakim revolted against Nebuchadnezzar. By the time the Babylonian army mobilized and made the long march to Jerusalem, Jehoiakim had been replaced by his son Jehoiachin. The city of Jerusalem was then taken. Jehoiachin, along with many leaders, including the priest Ezekiel, were taken into exile in Babylon. Nebuchadnezzar then placed on the throne Jehoiachin’s uncle, who took the name “Zedekiah.”

Yet, in 586 BC even Zedekiah presumed to rebel against Nebuchadnezzar. This time Nebuchadnezzar defeated Jerusalem, and he killed Zedekiah’s sons, gouged out his eyes, and carted him off to Babylon. He also destroyed much of the city, including the palace, walls, and temple. The book of Lamentations records the horrified reaction of the faithful to the destruction of the city. He exiled many of the leading citizens, but he left most of the people in the land under the leadership of Gedaliah, a Judean-born governor. Jeremiah records the account of later atrocities of an insurgent, Ishmael (Jer. 40:7–41:15). Ishmael’s assassination of Gedaliah and murder of the Babylonian soldiers in Jerusalem led to yet another Babylonian incursion into Judah in 582 BC.

Nebuchadnezzar died in 562 BC. He was succeeded by his son Amel-Marduk (known in the Bible as Awel-Marduk [2 Kings 25:27]).

The most intimate portrait of Nebuchadnezzar comes from Dan. 1–4. After taking Daniel and the three friends into captivity, he trained them for royal service. Daniel became a trusted adviser to the king. In the end, it was Daniel who taught the king rather than the other way around. It is doubtful that Nebuchadnezzar ever worshiped the true God exclusively, but he came to recognize Yahweh’s great power and wisdom.

Nebuchadrezzar See Nebuchadnezzar.

Nebushasban See Nebushazban.

Nebushazban The chief officer of King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon (r. 605–562 BC), he was one of several Babylonian officials who ordered Jeremiah’s removal from the courtyard during the fall of Jerusalem in 586 BC (Jer. 39:13 [KJV: “Nebushasban”]).

Nebuzaradan A Babylonian official, “the commander of the guard” (2 Kings 25:11), who appears in the biblical text at the fall of the city of Jerusalem in 586 BC. Nebuzaradan is credited with the complete razing of the temple, city structures, and defenses of Jerusalem (2 Kings 25:8–10). He also took many of the notable citizens into exile and left the poor behind (2 Kings 25:11–12). On instructions from Nebuchadnezzar, Nebuzaradan treated Jeremiah well (Jer. 39:11–14). Nebuzaradan returned to the land of Judah a few years later and took another 745 captives into exile (Jer. 52:30).

Necho Necho II was the third pharaoh of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt (r. 610–595 BC). In 609 BC Necho led the Egyptian army through Syria-Palestine to help support the crumbling Assyrian Empire at Harran against the encroaching Babylonians. Necho’s goal was to consolidate Egyptian power over the region from Egypt to the Euphrates. While Necho was traveling through Israelite territory, King Josiah of Judah led his army to confront Necho and forced a battle near Megiddo (2 Kings 23:29–35; 2 Chron. 35:20–36:4; cf. Jer. 46:2). Necho had warned Josiah that he was only passing through, but the battle went forward, and Josiah was killed. Three months later, after the Egyptian and Assyrian armies were unsuccessful in battle, Necho summoned Josiah’s son Jehoahaz to Riblah in Syria and deposed him, taking him into exile in Egypt. In his stead, Necho renamed Josiah’s older son Eliakim, calling him “Jehoiakim,” and placed him on the throne of Judah. This made Judah a vassal of Egypt, and Necho required a heavy tribute of gold and silver from Jehoiakim. Four years later, Necho again led the Egyptian army in battle against Babylon at Carchemish and shortly thereafter at Hamath, both serious defeats for Necho. Soon Nebuchadnezzar was campaigning in Palestine, and Jehoiakim switched his allegiance (and vassal loyalty) from Egypt to Babylon. Necho II was able to prevent Nebuchadnezzar and the Babylonian army from invading Egypt, but he never came farther east than Gaza from that time forward.

Nechoh See Necho.

Neck In the Bible, the neck often is associated with a burden. In several places the Bible refers to oppression or servitude as a yoke around one’s neck (Gen. 27:40; Deut. 28:48; Jer. 28:10–14). The apostle Peter even likened following the Mosaic law to bearing a yoke on one’s neck (Acts 15:10). The neck was also associated with adornment. Having jewelry placed around one’s neck was a sign of honor (Gen. 41:42; Dan. 5:16). Similarly, good instruction or moral character could be described as jewelry around one’s neck (Prov. 1:8–9; 3:21–22).

Necklace A neck ornament, often of high value, used to enhance beauty (Song 1:10; 4:9; Ezek. 16:11). Occasionally, a necklace signifies high office (Gen. 41:42; Dan. 5:29). See also Jewels, Jewelry.

Syrian necklace (fourth or fifth century BC)

Neco See Necho.

Necromancy The divination practice of consulting with the dead. Along with other forms of divination, sorcery, and magic, necromancy is strictly prohibited in Deut. 18:9–13. An example of necromancy, however, is recorded in 1 Sam. 28, where King Saul, devoid of any word from God due to the king’s repeated disobedience, persuades a “medium” to bring up Samuel from the dead to give guidance.

Nedabiah One of the sons of King Jehoiachin (Jeconiah) of Judah, who was carried off into Babylonian exile (1 Chron. 3:18).

Needle No biblical texts describe an ancient needle, but archaeologists have found needles made of bronze, bone, and ivory. The needle would have been sharp at one end, with an eye for thread at the other, similar at least in basic form to the modern needle. Simple sewing is the obvious use for needles, but they also played a larger role in embroidery, which was seen as a gift from God (Exod. 35:35; cf. 31:6; see also Needlework). The use of the needle is implied in certain contexts where sewing is present, such as Gen. 3:7.

The only mention of the word “needle” in the Bible is in the reference to the “eye of a needle” in the Synoptic Gospels (Matt. 19:24; Mark 10:25; Luke 18:25). The purpose here is to contrast one of the smallest openings common to the household with one of Palestine’s largest animals. This comparison is an example of hyperbole, expressing the great difficulty that the rich would encounter in abandoning all to follow Christ.

Needlework Also called “embroidery,” the interweaving of various colors of thread to form decorative patterns, as seen in the tabernacle curtains. A high degree of skill was involved, as is evident in descriptions of these curtains: “Make the tabernacle with ten curtains of finely twisted linen and blue, purple and scarlet yarn, with cherubim woven into them by a skilled worker” (Exod. 26:1). Needlework was viewed as a skill given by God (Exod. 35:35). Embroidered garments were a sign of luxury, worn by the affluent and the high priest (Exod. 28:39). They were a trade commodity (Ezek. 27:16) and a spoil of war, prized by many (Judg. 5:30).

Neesings In Job 41:18 the KJV translates the Hebrew ’atishah as “neesings,” referring to the “snorting” (NIV) or “sneezing” (NRSV) in the description of Leviathan.

Negeb See Negev.

Negev This arid region, whose name sometimes is translated as “the south,” extends from Judah to the Gulf of Aqaba and includes the Desert of Paran. Abraham and Isaac both lived in the northern part of the Negev (Gen. 20:1; 24:62). Part of Israel’s wilderness wanderings took place in the Negev (Num. 13:17), and they encountered the Amalekites there (Num. 13:29). Joshua conquered this region and allotted it to Judah and Simeon (Josh. 10:40; 15:21; 19:8). When David conducted raids against the Geshurites, the Girzites, and the Amalekites, he told the Philistines that he was attacking the Negev (1 Sam. 27:10). The Negev is also referenced in poetic and prophetic texts (Ps. 126:4; Isa. 21:1; 30:6; Jer. 13:19; 17:26; Zech. 7:7).

Neginah, Neginoth A transliteration of a Hebrew word (sg. and pl.) that appears in the superscription of a number of psalms (Pss. 4; 6; 54–55; 61; 67; 76). While the KJV transliterates the term in these psalm superscriptions as “Neginah, Neginoth” (but cf. Hab. 3:19 KJV), most modern versions, like the NIV, understand it to mean “stringed instruments.” In several other passages the Hebrew term refers to a mocking song or taunt (Job 30:9; Ps. 69:12; Lam. 3:14).

Nehelam, Nehelamite This name is associated with Shemaiah, a false prophet in Babylon of Jeremiah’s day (Jer. 29:24–32). It is uncertain whether “Nehelam” is a family name or a place name. Shemaiah had sent a letter to the priest Zephaniah, criticizing him for not reprimanding Jeremiah for his negative prophecies. In response, Jeremiah pronounced judgment from God against Shemaiah and his descendants. See also Shemaiah.

Nehemiah (1) The son of Hakaliah, he was a prominent leader of the people of God in the late postexilic period (Neh. 1:1–7:73; 8:9–10; 10:1–13:31). He returned to Jerusalem from the Persian capital, Susa, in order to rebuild the wall of Jerusalem and to fortify the morale of its citizens.

Before his return to Jerusalem, Nehemiah worked as the cupbearer to the king of Persia, Artaxerxes. There are three kings by that name during the history of the Persian Empire, but scholars are generally agreed that Nehemiah worked for Artaxerxes I (r. 464–424 BC). The job of the cupbearer was an important one. The king needed to rely on a close confidante to serve him his drink, since poisoning was an occupational hazard for ancient kings.

Although he was in a powerful position in Persia, Nehemiah was deeply saddened to hear the condition of Jerusalem from his visiting brother Hanani. In particular, the city’s walls were torn down and its gates were burned. While we might assume that the condition of the gates was the result of the Babylonian incursion into the city decades before (587/586 BC), it is possible, though not provable, that a more recent event was responsible.

In either case, Nehemiah could not hide his grief as he served Artaxerxes. Artaxerxes then granted him permission to return to Jerusalem and see to the restoration of the city. The king appointed Nehemiah governor of the Persian province of Yehud (Judah), and he returned to Jerusalem in the king’s twentieth year (445 BC).

A contract from the time of Artaxerxes I, king of Persia during the time of Nehemiah

Even though Nehemiah had the support of the Persian king, the inhabitants of the land and its leaders, notably Sanballat, did everything they could to undermine his efforts. These people were Samaritans from the north who were the descendants of intermarriage between the people of the north and those whom the Assyrians forced to immigrate there after their defeat of the northern kingdom of Israel in 722 BC. In spite of this opposition, Nehemiah successfully led the people in their efforts to rebuild the walls. In doing so, he showed great leadership skills and courage.

Although they are not often mentioned together, Nehemiah’s work in Jerusalem overlapped with that of Ezra. Both men were passionately concerned about the integrity and faithfulness of the people. Both of them at different times confronted Jewish men who divorced their wives and married pagan women. Nehemiah forcefully compelled them to divorce these foreign wives out of fear that the wives would lead their Jewish husbands to worship false gods.

Nehemiah worked hard, and God blessed him and his efforts in many ways. Even so, the account of Nehemiah’s work ends on a note of continuing problems as the people continued sinning (Neh. 13).

(2) A man who returned to Jerusalem from Babylon along with Zerubbabel in 539 BC (Ezra 2:2).

(3) The son of Azbuk, ruler of a half-district of Beth Zur, he helped rebuild the walls and gates of Jerusalem under the direction of Nehemiah son of Hakaliah (Neh. 3:16).

Nehemiah, Book of Nehemiah son of Hakaliah is one of the most colorful figures in OT history. He is passionate and aggressive; he works hard to achieve the goals that God has set for him. He does not tolerate the sins of others and fights his way through the obstacles that people set in his path. In many ways, he is a study in contrasts with Ezra, his near contemporary. When Ezra discovers sin among his fellow Judeans, he pulls his hair out. When Nehemiah encounters the same problem, he pulls out the hair of the sinners.

The books of Ezra and Nehemiah were originally a single composition, not broken into two parts until the Middle Ages. Thus, many issues, such as date and authorship, are discussed in the introduction to the article on the book of Ezra. Here, the conclusions will be stated for ease of reference, but the evidence is presented in the article on Ezra. The additional details to follow are particularly relevant to the study of Nehemiah.

LITERARY CONSIDERATIONS

Author and date. Ezra-Nehemiah is an anonymous composition that reached its present form sometime between 400 and 300 BC.

Genre and structure. Ezra-Nehemiah is a theological history, a book that intends to communicate what actually happened in space and time but is selective, with the purpose of showing how God was working among his people in the postexilic period. As a theological history in the OT, however, Ezra (and Nehemiah) are unique in that they contain the memoirs of Ezra and Nehemiah as detailed by the first outline below. The structure of the book of Ezra makes sense only when paired with the book of Nehemiah, again since they were originally a unit. The structure may be explained on the basis of its sources, as follows:

I. A Historical Review (Ezra 1–6)

II. Ezra’s Memoirs, Part 1 (Ezra 7–10)

III. Nehemiah’s Memoirs, Part 1 (Neh. 1–7)

IV. Ezra’s Memoirs, Part 2 (Neh. 8–10)

V. Nehemiah’s Memoirs, Part 2 (Neh. 11–13)

Or it may be explained on the basis of its content:

I. Zerubbabel and Sheshbazzar Lead the People in Rebuilding the Temple (Ezra 1–6)

II. Ezra Leads the People by Reestablishing the Law (Ezra 7–10)

III. Nehemiah Leads the People in Rebuilding the Wall of Jerusalem (Neh. 1:1–7:3)

IV. Renewal, Celebration, Remaining Problems (Neh. 7:4–13:31)

THEOLOGICAL MESSAGE

The book begins with Nehemiah serving as the cupbearer of King Artaxerxes of Persia. Nehemiah hears a distressing report from his ancestral homeland in Judah and feels called to return to Jerusalem. Receiving permission from Artaxerxes to go back to Judah, he arrives intent on building the walls of the city, thus completing the physical reconstruction of the city. In spite of the efforts of neighboring groups and provinces to block their efforts, the Jews under Nehemiah’s leadership are remarkably successful at accomplishing their task. In this, the postexilic people of God surely must have recognized that the prophecies of salvation in Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel were coming to fulfillment.

The book of Nehemiah also records Ezra’s leadership in guiding the people to reaffirm their commitment to Yahweh and his law. They confess their sin. One might think of the physical wall that Nehemiah built not only as protection but also as a means of physical separation from the Gentiles. Also, then, Ezra’s reestablishment of the law of God would serve as a spiritual separation from the lawless Gentiles.

Even with all the success, the book of Nehemiah ends in chapter 13 on a note of disappointment. Nehemiah recounts the strenuous efforts that the faithful under his leadership have made to get right with God, but many people persisted in their sin.

CONTEMPORARY SIGNIFICANCE

Ezra narrates two returns: first under Zerubbabel and Sheshbazzar to rebuild the temple, and second under Ezra to reestablish the law. In the first part, the book of Nehemiah focuses on a third return under Nehemiah to build the walls and thus complete the physical reconstruction of the city. Nehemiah’s leadership provides an alternative model of leadership to that of Ezra. Nehemiah is more assertive and demanding. It is not that one mode of leadership is right or wrong; the contemporary Christian leader looking to Ezra and Nehemiah for a model of leadership should read the situation to know what will best accomplish God’s purposes. Also, the purpose of building the walls was a matter of military defense, but it was also a matter of separation. True, Christ breaks down the wall of separation between Jews and Gentiles (Eph. 2:14–18), but the NT also recognizes that Christians (whether from a Jewish or a Gentile background) must lead holy and distinct lives.

Surprisingly, the book of Nehemiah does not end with a sense of completion, a feeling of mission accomplished. The last chapter finds Nehemiah in prayer for the continuing sin of the people, reminding contemporary readers that repentance is not a onetime act, but a lifestyle.

Nehiloth The KJV transliteration of a word of uncertain meaning that occurs in the superscription of Ps. 5. Most modern versions render the word as “flutes” or “pipes” (NIV).

Nehum A leader who returned with Zerubbabel from the Babylonian exile (Neh. 7:7). He may be the same person as the Rehum of Ezra 2:2.

Nehushta The mother of King Jehoiachin (2 Kings 24:8). She was the daughter of Elnathan and from Jerusalem. She was taken to Babylonia with her son when Nebuchadnezzar conquered Jerusalem in 597 BC (2 Kings 24:15; Jer. 29:2). She is likely mentioned in Jer. 13:18.

Nehushtan In 2 Kings 18:4 the name given to the bronze snake that Moses made during the wilderness journey. In one of many incidents in which the Israelites grumbled against Moses, God sent poisonous snakes against the people (Num. 21:4–9). When they confessed their sin and cried out to Moses for relief, God directed him to make the bronze snake and erect it on a pole. Anyone who looked at it would live. Apparently, this object was kept and preserved over the centuries, for it still existed in King Hezekiah’s time. Being a sacred relic, it had become an object of idolatry. The king destroyed it as part of his spiritual reforms.

Neiel A town on the eastern border of the land allotted to Asher (Josh. 19:27). Most identify Neiel with Khirbet Yanin, located approximately nine miles west of Akko, near where the Plain of Akko gives way to the hills of Galilee.

Neigh A cry characteristic of a horse (see Jer. 8:16). It is used in a figurative sense in Jer. 5:8 (cf. 13:27) to depict Judah’s lust.

Neighbor In the OT, “neighbor” is derived from the verb “to associate with.” This is an important connection because relationships of various kinds are central to the issue of neighbor. Depending on the context, a neighbor can include a friend (2 Sam. 13:3), a rival (1 Sam. 28:17), a lover (Jer. 3:1), or a spouse (Jer. 3:20). However, “neighbor” essentially defines someone who lives and works nearby, those with shared ethical responsibilities, rather than a family member (Prov. 3:29). Eventually, “neighbor” acquired the more technical meaning of “covenant member” or “fellow Israelite” (= “brother” [Jer. 31:34]). The legal literature prohibits bearing false witness against a neighbor (Deut. 5:20) as well as coveting a neighbor’s house, animal, slave, or wife (Deut. 5:21). Fraud, stealing, or withholding from a neighbor are prohibited (Lev. 19:13; Ps. 15:3). These are the negative stipulations. The theological ethics that arise from Lev. 19 are climactic—ethically, politically, socially, and economically. Positively, Israelites are to judge their neighbors justly (Lev. 19:15), loving their neighbors as themselves (19:18). Even the resident alien is to be protected by these core moral virtues (Lev. 19:33–34; cf. Exod. 12:43–49).

When the NT addresses the topic, not surprisingly it is Lev. 19:18 that is routinely cited. Asked about the greatest commandment, Jesus quotes Lev. 19:18 as the horizontal counterpart to loving the Lord (Matt. 19:16–30). A lawyer’s question put to Jesus, “Who is my neighbor?” elicits the parable of the good Samaritan (Luke 10:29). Jesus teaches that extending mercy is more important than conveniently defining “neighbor.” A neighbor was anyone someone met in need—Jew, Gentile, or Samaritan (Luke 10:25–37). Jewish law came to define “neighbor” in purely legal terms within Judaism. Jesus addressed the limits of one’s responsibility, challenging the particularism of Judaism, denouncing prejudiced love, and including non-Jews. Beyond “in” or “out” groups, believers are now to pray for their enemies (Matt. 5:43–48). Mission work continues to expand social, political, and economic boundaries. The OT reality of relationships is still in force, but “neighbor” in the NT now prioritizes fellow believers (Rom. 13:8–10; 15:2; Gal. 6:10; Eph. 4:25; James 2:8).

Nekeb In Josh. 19:33 the KJV takes “Nekeb” as a place name in the description of the tribal allotment given to Naphtali: “from Allon to Zaanannim, and Adami, Nekeb, and Jabneel.” Most modern versions treat “Adami” and “Nekeb” as two parts of one name: “Adami Nekeb” (NIV) or “Adami-nekeb” (NRSV, NLT). Adami Nekeb is identified as a city or town between the Sea of Galilee and Mount Tabor. Its precise location is uncertain.

Nekoda (1) One of the ancestors of the temple servants (Nethinim) who returned to Jerusalem after the Babylonian captivity under the leadership of Zerubbabel (Ezra 2:48; Neh. 7:50). The fact that many of the names in the list are foreign has led to the belief that they were originally prisoners of war who were pressed into service to perform menial tasks as they assisted the Levites. (2) The patronymic ancestor of a family that could not establish its Israelite background after the exile (Neh. 7:62).

Nemuel (1) The first of the three sons of Eliab, a Reubenite. His brothers, Dathan and Abiram, rebelled against Moses and Aaron and died in the Korah rebellion (Num. 26:9). (2) A son of Simeon and the eponymous ancestor of the Nemuelites (Num. 26:12; 1 Chron. 4:24). In Gen. 46:10; Exod. 6:15 his name is “Jemuel.”

Nemuelites See Nemuel.

Nepheg (1) A Levite, one of the three sons of Izhar, who was a brother of Amram, Moses’ father (Exod. 6:21). (2) A son of David born to an unnamed wife during the time he reigned from Jerusalem (2 Sam. 5:15; 1 Chron. 3:7; 14:6).

Nephesh See Naphish.

Nephew The son of one’s brother or sister. Many modern versions use the term of Lot as Abraham’s nephew (Gen. 12:5; 14:12) and in Ezra 8:19 of the nephews of Hashabiah, a descendant of the Levite Merari, returnees to Jerusalem. The KJV uses “nephew” in an archaic sense of a descendant, usually referring to grandson (Judg. 12:14; Job 18:19; Isa. 14:22; 1 Tim. 5:4).

Nephilim The Hebrew word nepilim occurs only in Gen. 6:4; Num. 13:33. Some translations render the word as “giants.” Literally, it means “fallen ones.” Some scholars have considered the Nephilim to be offspring from the unions between the “sons of God” and the “daughters of humans,” but it is also possible that the writer was distinguishing between the Nephilim and the children of those unions who became the “heroes of old” and “men of renown” (Gen. 6:4). Descendants of the Nephilim were purported to have also lived after the flood (Deut. 2:10–11, 20–23; Josh. 14:15; 15:13–14; 2 Sam. 21:16–22; 1 Chron. 20:6–8). Since the entire human race, except for Noah and his family, was destroyed in the deluge, these descendants who lived in Canaan at the time of the exodus most likely descended through Ham, one of Noah’s sons (Gen. 10:8–20).

Nephish See Naphish.

Nephishesim, Nephisim See Nephusim.

Nephthalim A variant spelling of “Naphtali” used in the KJV (Matt. 4:13, 15; Rev. 7:6). “Nephthalim” transliterates the Greek spelling of the Hebrew name.

Nephtoah A spring of water that formed part of the northern geographical boundary of the tribe of Judah (Josh. 15:9) and part of the southern geographical boundary of the tribe of Benjamin (18:15). The spring is a few miles northwest of Jerusalem.

Nephushesim See Nephusim.

Nephusim A person listed among the returnees from the Babylonian captivity with Zerubbabel (Ezra 2:50; Neh. 7:52). In some English translations the name is spelled differently in Ezra and in Nehemiah (e.g., KJV, ESV, NRSV, NASB).

Nephussim See Nephusim.