W

Wadi A ravine, gorge, valley, or streambed, sometimes steep, in an arid region that is dry except during rainy season, when it becomes susceptible to torrential, life-threatening flash flooding. Job compares his fickle friends to a wadi (Job 6:15–20; NIV: “intermittent streams”]).

Feran Wadi in Egypt

Wadi of Egypt Also known as the Brook of Egypt (ESV, NASB, NKJV), it is the southwestern limit of the territory given to Israel (the Euphrates being the northern boundary). It was promised to Abram in Gen. 15:18. It is likely identified as the Wadi el-Arish, which flows from the middle of the Sinai Peninsula to the Mediterranean Sea (Num. 34:5; Josh. 15:4, 47).

Wadi of the Willows See Arabim.

Wages Payment for the hire of one’s labor, often disbursed daily. The Bible refers to wages in connection with various occupations, including agricultural worker (Gen. 29:15; 30:27–29; Zech. 11:12; Matt. 20:1–16; John 4:36), artisan (1 Kings 5:6; Isa. 46:6), soldier (2 Chron. 25:6; Ezek. 29:18–19; 1 Cor. 9:7), prostitute (Hos. 9:1; Mic. 1:7), priest (Judg. 18:4; Num. 18:31), nurse (Exod. 2:9), and even the beast of burden (Exod. 22:15; Zech. 8:10; 1 Tim. 5:18). Prophets were paid for their work (Amos 7:12), though a late OT and Second Temple period tradition regarded the sin of Balaam as prophecy for hire (Deut. 23:4; Neh. 6:12–13; 13:2; 2 Pet. 2:15; Jude 11). In the NT, the concept of wage labor is extended to the church leader and the apostle (Luke 10:7; 1 Cor. 3:8; 1 Tim. 5:18).

Behind many references in the NT to wages lies the Latin term denarius (Gk. dēnarion) a small silver coin equivalent to a day’s wages (as in Matt. 20:2). Thus, in Mark 6:37 “more than half a year’s wages” (NIV) translates what in Greek is “two hundred denarii” (NRSV) (see also Mark 14:5), and the commodity prices in Rev. 6:6 show massive inflation relative to the day’s wage or denarius. In addition to the payment of wages with money, the Bible attests the payment of wages in kind, including wives (Gen. 29:17), livestock (Gen. 30:32), food (Num. 18:31; 1 Sam. 2:5), and, in the case of soldiers, plunder (Ezek. 29:19).

Several texts regard the fair payment of wages as a basic element of social justice and, conversely, the withholding of wages as an evil. Deuteronomy 24:15 commands the employer to pay workers wages “each day before sunset, because they are poor and are counting on it” (cf. Lev. 19:13; Job 7:2). Likewise, Mal. 3:5 denounces those who defraud workers of wages (cf. Gen. 31:2), a stance continued in the NT (Rom. 4:4; James 5:4).

The reward of righteousness and the punishment of wickedness are described as a wage, as in Rom. 6:23: “The wages of sin is death.” Proverbs 10:16 says, “The wages of the righteous is life, but the earnings of the wicked are sin and death” (cf. Prov. 11:18; Isa. 65:7; 2 Pet. 2:13).

Wagon See Cart; Litter.

Waheb See Zahab.

Wail See Grief and Mourning; Repentance.

Walk Walking was the primary mode of transportation in Bible times, and metaphorically it referred to one’s conduct of life. It is used figuratively in both Testaments. For example, Noah is introduced as a righteous and blameless man who “walked faithfully with God” (Gen. 6:9), and Christians are to “walk in the light” (1 John 1:7) and “walk just as [Jesus] walked” (1 John 2:6 NRSV).

Wall, Angle of the In 2 Chron. 26:9; Neh. 3:19–20, 24–25 reference is made to the “angle” (Heb. miqtsoa’) of the Jerusalem wall (NRSV: “the Angle”; KJV: “the turning of the wall”). It refers not to a main corner of the wall but perhaps to a projection of or indentation in the wall’s course.

Wall, Dividing The NIV renders the Greek word mesotoichon in Eph. 2:14 as “dividing wall” (KJV: “middle wall”). Within the temple infrastructure stood a wall of one and a half meters. This temple balustrade separated the court of the Gentiles from the inner courts and the sanctuary in the Jerusalem temple. Because the wall is a powerful symbol of the separation of Gentiles from Jews, the NT declaration that this wall has been broken down is rhetorically significant (Eph. 2:14; cf. 1 Macc. 9:54). Christ has (symbolically) broken down this dividing wall through his death. Jews and Gentiles now stand as one as they approach God.

A difficulty in this interpretation of Eph. 2:14, however, is that the “dividing wall” in the temple was still standing until the destruction of the temple in AD 70. It seems preferable to see the reference to the “dividing wall” as an ad hoc formulation coherent to the context of Eph. 2:14. The writer continues with the partitioned house/temple theme in 2:19 and refers to the “holy temple” in 2:21. It was the purposeful and exclusive attitudes of the Jews that separated Jew from Gentile and created a barrier between them. This social barrier would have been closely associated with some of the boundary markers used by Jews to separate themselves from Gentiles.

Walls Walls were necessary defense architecture surrounding a city or a fortress (e.g., Deut. 3:5; Josh. 2:15; 1 Sam. 31:10). Unlike the stone fence that protected vineyards, orchards, or gardens (Prov. 24:31; cf. Eccles. 10:8), walls were constructed of unbaked mud-brick or stone and enhanced with features such as a glacis (ramparts), supporting retaining walls, dry moats, and towers. By the time of the Early Bronze Age (3300–2200 BC), some cities were even fortified by two layers of walls, supported in between by a glacis.

Two types of walls have been discovered in Palestine: casemate walls and solid walls. Casemate walls consisted of two parallel walls joined by a short wall filled with rubble at regular intervals, forming a series of casemates. After the Solomonic era, however, the main fortifications were solid walls that were offset-inset, with projecting and receding sections built into the wall face to give a better defense against battering rams and scaling ladders.

War See Holy War.

War Crimes Atrocities in violation of laws and customs constraining the injurious actions of belligerents against their enemies. These include the killing of civilians, the mistreatment of prisoners of war, the wanton destruction of nonstrategic targets, and genocide.

War crimes were first identified during the 1474 tribunal of the knight Peter von Hagenbach in the Holy Roman Empire. He was beheaded for heinous offenses against the people of the upper Rhine, despite his protest that he was only following orders issued by the Duke of Burgundy. Currently, war crimes are governed by the Third (1929) and Fourth (1949) Geneva Conventions.

The biblical case against war crimes is the product of wise exegesis, as many of Israel’s OT battles feature elements of brutality shocking to modern readers (Josh. 6:20–21; Judg. 9:45, 49; 1 Sam. 22:19; Ps. 137:7–9). However, it is important to realize that such practices were contextually customary, being executed in an attempt to purify the land of Canaan and, in the case of kherem warfare (i.e., devotion to destruction), prescribed by Yahweh as a sacrificial offering. Further, they are accompanied by passages reiterating that vengeance belongs to God (Deut. 32:35; Ps. 94:1; Heb. 10:29–31), and they must be read in light of the NT imperatives to love one’s enemies (Matt. 5:44; Luke 6:27) and treat them with compassion (Rom. 12:17–21). See also Holy War; Vengeance.

Washerman’s Field The road to the Washerman’s Field (NIV: “Launderer’s Field” in Isa. 7:3; 36:2) locates where Ahaz was inspecting Jerusalem’s water supply in preparation for an attack by Syria and Israel (Isa. 7:3), and where the Assyrian commander stood (2 Kings 18:17; Isa. 36:2). Jerusalem was supplied by a series of pools connected by channels. The launderer’s occupation of cleaning cloth required much water (cf. Mal. 3:2). The field was located outside the city, at its southern end.

Washing See Ablutions; Bathing.

Watch A chronological division of the night. The term is derived from soldiers or others guarding, or “watching,” something during specified portions of the night. In the OT, there apparently were three watches or divisions in the night. Gideon and his men struck the Midianites at the beginning of the “middle watch” (Judg. 7:19). The Roman system had four divisions or watches in the night, and the Gospels report Jesus walking on the lake during the “fourth watch” (Matt. 14:25; Mark 6:48 ESV, NASB, NKJV). The term can also be used to refer to the guard placed on duty to guard something (Neh. 4:9).

Watchman The watchman was stationed on the city wall or in a watchtower. He was to identify potential enemies approaching the city and alert the city’s inhabitants by blowing a trumpet (Jer. 6:17; Amos 3:6). It was the duty of some watchmen to inform the king of any suspicious person approaching the city wall (2 Sam. 18:24–27). Just as the watchman warned of potential danger so that people could prepare themselves, so the prophet was to warn of impending judgment on the unrighteous (Ezek. 33:1–11).

Watchtower Military watchtowers could be part of city battlements (Isa. 21:8) or more-isolated lookouts (2 Chron. 20:24 NRSV). Vineyards also had watchtowers (Isa. 5:2; Matt. 21:33; Mark 12:1).

Water Water is mentioned extensively in the Bible due to its prevalence in creation and its association with life and purity. The cosmic waters of Gen. 1 are held back by the sky (Gen. 1:6–7; cf. Pss. 104:6, 13; 148:4). God is enthroned on these waters in his cosmic temple (Pss. 29:10; 104:3, 13; cf. Gen. 1:2; Ps. 78:69; Isa. 66:1). These same waters were released in the time of Noah (Gen. 7:10–12; Ps. 104:7–9).

Water is also an agent of life and fertility and is therefore associated with the presence of God. Both God himself and his temple are described as the source of life-giving water (Jer. 2:13; 17:13; Joel 3:18; cf. Isa. 12:2–3). Ezekiel envisions this water flowing from beneath the temple and streaming down into the Dead Sea, where it brings life and fecundity (Ezek. 47:1–12; cf. Zech. 14:8). The book of Revelation, employing the same image, describes “the river of the water of life, as clear as crystal, flowing from the throne of God and of the Lamb” (22:1). This imagery is also illustrated in archaeological remains associated with temples. Cisterns are attested beneath the Dome of the Rock (presumably the location of the Jerusalem temple) and beneath the Judahite temple at Arad. Other temples, such as the Israelite high place at Tel Dan, are located close to freshwater springs. The Gihon Spring in the City of David may also be associated with the Jerusalem temple (Ps. 46:4; cf. Gen. 2:13).

This OT imagery forms the background for Jesus’ teaching regarding eternal life in the writings of the apostle John. Jesus claims to be the source of living water, and he offers it freely to everyone who thirsts (John 4:10–15; 7:37; Rev. 21:6; 22:17; cf. Rev. 7:17). This water, which produces “a spring of water welling up to eternal life” (John 4:14), is the work of the Holy Spirit in the believer (John 7:38–39).

Water is also described in the Bible as an agent of cleansing. It is extensively employed in purification rituals in the OT. In the NT, the ritual of water baptism signifies the purity and new life of the believer (Matt. 3:11, 16; Mark 1:8–10; Luke 3:16; John 1:26, 31–33; 3:23; Acts 1:5; 8:36–39; 10:47; 11:16; 1 Pet. 3:20–21; cf. Eph. 5:26; Heb. 10:22).

Finally, the NT also reveals Jesus as the Lord of water. He walks on water (Matt. 14:28–29; John 6:19), turns water into wine (John 2:7–9; 4:46), and controls water creatures (Matt. 17:27; John 21:6). Most important, Jesus commands “the winds and the water, and they obey him” (Luke 8:25; cf. Ps. 29:3).

Water Carriers Persons engaged in the menial tasks of drawing and carrying water. This chore, typically coupled with cutting wood, often was performed for others in power (Deut. 29:11; Josh. 9:21, 23, 27).

Water Jar A jar or vessel made for carrying water. The vessel normally was made of clay, but also could be stone. In the ancient Near East women often carried the smaller pots upon their shoulder or head (see John 4:28). Larger stone pots could be used to store water. Jesus’ first miracle involved turning water from large water jars into wine (John 2:6). See also Vessels and Utensils.

Water of Bitterness, Water of Jealousy See Bitter Water.

Waterpot See Water Jar.

Waters of Merom See Merom.

Wealth and Materialism Both the OT and the NT view wealth as ultimately a result of God’s blessing (Prov. 10:22). Abraham shows the right attitude by refusing to accept plunder from the king of Sodom, recognizing God as the sole source of his riches (Gen. 14:23). Solomon’s wealth was seen as God’s favor (1 Kings 3:13). Wealth and riches are said to be in the house of persons “who fear the LORD” (Ps. 112:1–3). However, material success alone is not necessarily an indication of God’s approval, nor is poverty a sign of God’s disfavor. Fundamentally, neither poverty nor wealth can be superficially tied to divine displeasure or favor.

Balanced view. The Bible articulates a balanced view of wealth. It warns against having an arrogant attitude by failing to acknowledge that the source of wealth is God (Deut. 8:17–18). There is danger in trusting in riches (Pss. 52:7; 62:10). The rich are charged not to be haughty, and to set their hopes not on uncertain riches but rather on God (1 Tim. 6:17–18). The love of money is described as the root of all kinds of evil (1 Tim. 6:9–10), and it is therefore extremely difficult for a rich person to enter the kingdom of God (Matt. 19:24). The foolishness of materialism, making riches the center of one’s life, is shown in the parable of the wealthy farmer (Luke 12:15–21). Instead of monetary greed, the spirit of contentment is commended, because even if lacking on the material level, one still has the Lord (Luke 12:15; Phil. 4:11; Heb. 13:5). Material possessions should be gained rightly; effort and diligence are required (Gen. 3:19; Prov. 10:4). Obtaining wealth through dishonesty and ill-gotten gains is denounced and condemned (Prov. 11:26; 13:11; Jer. 17:11; Mic. 6:12).

Wealthy Jewish home in Jerusalem

God-centered perspective. Wealth and material possessions are to be viewed from a God-centered perspective. God is the one who provides everything; thus we should trust him for our daily needs (Matt. 6:25–34; Luke 11:3). Job’s confession in a time of loss, “The LORD gave and the LORD has taken away; may the name of the LORD be praised,” shows an admirable attitude to emulate (Job 1:21). God is the owner of all things, and we are simply stewards and administrators of God’s wealth. We need to remember that one day we will be accountable for the use of our wealth (1 Cor. 10:31). Jesus teaches us to seek the kingdom of God first rather than his material blessings (Luke 12:31–33). Anything that draws us away from serving God should be avoided. We cannot serve both God and mammon (Matt. 6:24). Our treasures are to be in heaven, meaning that our central focus should be on matters pertaining to the kingdom: “Where your treasure is, there your heart will be also” (Luke 12:32–34).

Responsibility and generosity. With the possession of wealth comes the duty to give generously to those in need (Prov. 11:24; 28:27). Prosperity is given as a means to do good; thus we ought to be rich in good deeds (1 Tim. 6:18). Although it is a duty of the covenant community to take care of the needy in the OT, it still emphasizes the voluntary heart (Deut. 15:5–11). In 2 Cor. 9:7, Paul presents the principle of giving in the NT: “Each of you should give what you have decided in your heart to give, not reluctantly or under compulsion, for God loves a cheerful giver.” It should be not an exaction but a willing gift (9:5).

The Christian should emulate Jesus: “Though he was rich, yet for [our] sake he became poor, so that [we] through his poverty might become rich” (2 Cor. 8:9). Therefore, material offerings to Christ should not be a burden (1 Cor. 9:11). Sacrificial giving is an expression of love to the Lord (2 Cor. 9:12). It also generates thanksgiving to God from those who receive it (2 Cor. 9:11). Worldly wealth should also be used for evangelistic purposes (Luke 16:8). If we are faithful in the use of money, we can be trusted with the kingdom’s spiritual riches (Luke 16:12–13). Although riches do not have eternal value in themselves, their proper use has eternal consequences (Luke 12:33; 1 Tim. 6:19). One of the qualifications of a church overseer is to be free from the love of money, and a deacon must not pursue dishonest gain (1 Tim. 3:3, 8). A good name is to be chosen over great riches (Prov. 22:1). James condemns as sinful the attitude of favoring the wealthy over the poor. Nonpreferential love is the answer to prejudicial favoritism (James 2:1–9).

Weapons Early weapons used shaped flint blades, which remained in use well after the advent of metal weaponry. These included knives, arrowheads, and simple axes with wooden handles. The invention of metal casting brought more-durable metal weaponry during the Chalcolithic (4500–3300 BC) and Bronze Ages (3300–1200 BC). At first, the most common weapons were axes and maces, which were most effective against soft targets. As technology and armor advanced, spears and swords became more important. The first swords of the ancient Near East developed during the Bronze Age; typically they were sickle shaped, with one cutting edge on the outer portion of the blade. The Late Bronze Age also saw the arrival of the composite bow, greater in range and power than previous bows. During the Iron Age (1200–586 BC), the days of the judges and the Israelite monarchy, the Philistines and other Sea Peoples brought new weapons, including an Aegean-style sword, which was a double-edged straight sword more akin to the medieval broadsword. Both iron and bronze weapons were used throughout the Levant until the tenth century BC, when iron replaced bronze as the dominant material for weaponry. See also Arms, Armor.

Weasel The Hebrew for the first unclean animal in Lev. 11:29, kholed, is translated as “weasel” in several versions (e.g., NIV, NRSV, KJV). Weasels are small, reddish-brown carnivores, indigenous to Israel until recently. With long bodies, short legs, and constant movement, they appear to “swarm” close to the ground. The mongoose and the polecat, more common in Israel, are somewhat similar.

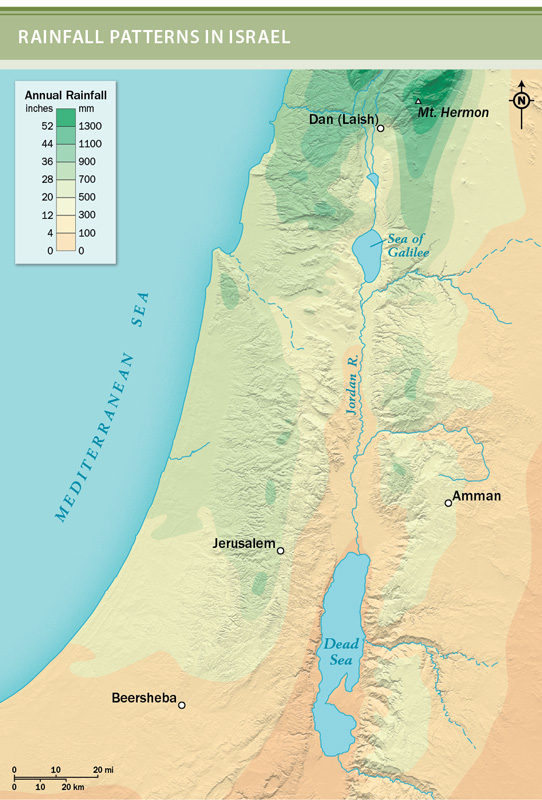

Weather Palestine has arid and wet Mediterranean climate zones and a steppe zone. Its two seasons are dry/summer and wet/winter (cf. Gen. 8:22). In summer the weather is remarkably stable, and the incoming air from the northwest typically is rather arid. With no cloud cover most days, there is, on average, zero rainfall from June through September—the background for the miracle of 1 Sam. 12:16–18 (cf. Prov. 26:1).

In winter the weather is variable, with rains and thunderstorms arriving from the Mediterranean Sea, generally from the southwest. The rains usually fall in concentrated amounts over a few hours. Rainfall diminishes overall from north to south and west to east, though varying elevations create deviations from the overall pattern. Annual rainfall varies significantly (from twelve to forty inches), falling almost entirely between November and April. Dew is a significant source of water in the region, especially in summer, sometimes constituting 25 percent of the annual moisture.

Table 11. Average Low–High Temperatures (°F)

| Month | Tel Aviv (sea level) | Jerusalem (2,500 ft.) | Tiberias (-650 ft.) | Jericho (-840 ft.) |

| January | 34–74 | 39–53 | 45–61 | 49–65 |

| February | 36–80 | 40–56 | 48–66 | 49–64 |

| March | 37–87 | 43–61 | 54–73 | 56–73 |

| April | 42–95 | 49–70 | 55–77 | 62–82 |

| May | 47–99 | 54–77 | 59–86 | 68–90 |

| June | 55–97 | 59–82 | 68–93 | 74–98 |

| July | 60–92 | 63–84 | 70–95 | 80–100 |

| August | 62–91 | 63–84 | 72–97 | 80–100 |

| September | 59–92 | 61–82 | 68–93 | 74–95 |

| October | 50–92 | 57–77 | 61–88 | 70–89 |

| November | 43–87 | 49–66 | 55–75 | 64–81 |

| December | 36–79 | 42–57 | 50–68 | 54–69 |

Apart from thunderstorms early in the rainy season, such as occur on the Sea of Galilee (cf. Luke 8:23), a high-pressure zone can form over Iraq during the wet season, forcing hot, dusty, and sometimes prolonged east winds into Palestine; these are called qadim in the Bible (Exod. 10:13; Ps. 48:7; Jon. 4:8). In the transitional periods between the two seasons, the sirocco (Arab. hamsin), may occur, in which an east wind from the Arabian desert sweeps up from the south and across Palestine toward a low-pressure zone over Egypt or Libya, causing humidity to drop as low as 10 percent and the temperature to rise as much as 22°F. This can last days or weeks, with sweltering effects (cf. Ezek. 17:10; Hos. 13:15; Luke 12:55). Such storms are often used as a backdrop to highlight the weakness and transience of earthly existence (Isa. 27:8; Hos. 12:1; James 1:11).

While various weather conditions are described throughout the Bible (rain, snow, storms, lightning, thunder, wind, etc.), Jesus refers specifically to weather prediction in Matt. 16:2–3, where he accuses the Pharisees of being able to predict the weather but not able to discern the signs of the times.

Weaver, Weaving See Spinning and Weaving.

Web Thread arranged on a loom for weaving (Judg. 16:13–14 [NIV: “fabric”]). Also, the silken netting spun by a spider as a snare is used as a negative metaphor for flimsiness and/or evil entrapment (Job 8:14–15; Isa. 59:5–6). More generally, “web” refers to an entangling mesh or net (Job 18:8).

Weddings Ceremonies marking entry into marriage. In the Bible, weddings initiate the formation of new households with the blessing of family and community.

OLD TESTAMENT

In the OT, weddings were important to the patriarchs and to Israel because the new couple was expected to produce children to help fulfill the Abrahamic covenant (Gen. 12:2; 17:6; 22:15–18; Ruth 4:11–13; Isa. 65:23). Heirs were also the assurance that a man’s name remained eternally with Israel, so much so that if a man died childless, his brother was obligated to wed the widow and produce children in his name (Gen. 38:8; Deut. 25:5–10). Moreover, weddings assured that property was kept within families and tribes and also transferred in an orderly way from one generation to the next (Num. 36:1–12; Ruth 4:5; Ps. 25:13).

Multiple wives were allowed in the OT (Gen. 30:26; Deut. 21:15; 1 Sam. 1:2; 2 Sam. 5:13; 1 Kings 11:3), as were multiple concubines, who had official standing in the household, though lower than that of wives. Weddings usually were associated with a man publicly taking a wife; he acquired concubines with less fanfare (Gen. 16:1–3; 30:3–5; Judg. 19:1, 3).

OT weddings included certain distinctive elements. The bridegroom or his father paid a bride-price, or dowry, to the father of the bridegroom’s prospective wife (Gen. 34:12; Exod. 22:16–17; 1 Sam. 18:25). The bridegroom had a more central role than the bride. He emerged from a chamber or tent to claim his wife (Ps. 19:5; Joel 2:16), who, in the case of a royal wedding, may have processed to him (Ps. 45:13–15). Both he and the bride were adorned (Song 3:11; Isa. 49:18; 61:10; Jer. 2:32); the woman was also veiled (Gen. 24:65; 29:23, 25; 38:14, 19; Song 4:1, 3; Isa. 47:1–3). Their wedding was the occasion of much rejoicing and feasting (Gen. 29:22; Jer. 7:34; 16:9; 25:10; 33:11) and lasted seven days (Gen. 29:27; Judg. 14:17). The main event was their sexual union (Isa. 62:5), which occurred on the first night (Gen. 29:23; Ruth 4:13). Unless she had been a widow, the bride was presumed to be a virgin on her wedding night, and evidence of her virginity, a bloodstained cloth, was retained as proof (Deut. 22:13–19). Virginity was essential to a previously unmarried bride; a woman who had been raped or otherwise engaged in premarital sexual relations was deemed defiled and unmarriageable to any but the first man with whom she had intercourse (Deut. 22:21; 2 Sam. 13:1–20). The importance of this underpins the shock value of the book of Hosea (see esp. 1:2), an extended metaphor that presents Israel as a prostitute nevertheless pursued by Yahweh as her husband.

NEW TESTAMENT

The NT continues to testify to many of these wedding traditions, significantly including the gathering of community (Matt. 22:2; John 2:1–2) in joyful celebration (Matt. 9:15; Mark 2:19; Luke 5:34; John 2:9–10). Wedding feasts could be lavish affairs (Matt. 22:4; John 2:6–10), with protocols regarding seating (Luke 14:8–10) and attire (Matt. 22:11–13; Rev. 19:7–9).

In the NT, these and other first-century wedding customs illustrate aspects of the kingdom of heaven. The parable of the wedding feast (Matt. 22:1–14) contrasts the invited guests (corrupt religious leaders in Israel) who ignored the king’s wedding invitation and murdered his servants with those people, good and evil, gathered from the streets (the downtrodden) who took their place. Their willingness to attend is qualified only by their coming properly attired in wedding robes, which by inference were provided by the king himself (Rev. 19:7–8).

The parable of the ten virgins (Matt. 25:1–13) plays on the understanding that weddings occurred not at a specific time but when the bridegroom was ready. His readiness was determined by, among other things, the readiness of a dwelling place for his new bride. In first-century Capernaum, this would have been a room or rooms built onto his father’s insula, a multifamily compound surrounding an interior courtyard; the same image is behind John 14:2–4. The parable, identifying the Son of Man as the bridegroom, illustrates that while his coming in glory is certain, its timing is unknown. Therefore, the bridal party is to be vigilant and prepared.

Elsewhere, Jesus is specifically named as the bridegroom preparing to marry his bride, the church (2 Cor. 11:2; Eph. 5:25–27, 31–32). The wedding feast at Cana (John 2:1–11), which begins Jesus’ public ministry, points proleptically to the marriage supper of the Lamb, which inaugurates the eschatological age (Rev. 19:7–9). The culminating picture of God with his people (Deut. 16:13–16; Matt. 1:23; John 1:14) is a magnificent wedding (Rev. 21:2, 9) between Christ and the new Jerusalem.

Week A week signifies a group of seven, most often a group of seven days marked by the Sabbath on the last day. The week serves as an important reminder of God’s creative activity (Exod. 20:11). The first day of the week prominently marks the resurrection of Jesus (cf. Matt. 28:1; Mark 16:9; Luke 24:1; John 20:1; Rev. 1:10). A week also describes a full period of time, as it is used in Daniel’s interpretation of Jeremiah’s prophecy regarding the return from exile (Dan. 9:24–27).

Weights and Measures It is difficult to imagine a world without consistent metrological systems. Society’s basic structures, from economy to law, require a uniform and accurate method for measuring time, distances, weights, volumes, and so on. In today’s world, technological advancements allow people to measure various aspects of the universe with incredible accuracy—from nanometers to light-years, milligrams to kilograms.

The metrological systems employed in biblical times span the same concepts as our own modern-day systems: weight, linear distance, and volume or capacity. However, the systems of weights and measurements employed during the span of biblical times were not nearly as accurate or uniform as the modern units employed today. Preexisting weight and measurement systems existed in the contextual surroundings of both the OT and the NT authors and thus heavily influenced the systems employed by the Israelite nation as well as the NT writers. There was great variance between the different standards used merchant to merchant (Gen. 23:16), city to city, region to region, time period to time period, even despite the commands to use honest scales and honest weights (Lev. 19:35–36; Deut. 25:13–15; Prov. 11:1; 16:11; 20:23; Ezek. 45:10).

Furthermore, inconsistencies and contradictions exist within the written records as well as between archaeological specimens. In addition, significant differences are found between preexilic and postexilic measurements in the biblical texts, and an attempt at merging dry capacity and liquid volume measurements further complicated the issue. This is to be expected, especially when we consider modern-day inconsistencies—for example, 1 US liquid pint = 0.473 liters, while 1 US dry pint = 0.550 liters. Thus, all modern equivalents given below are approximations, and even the best estimates have a margin of error of + 5 percent or more.

WEIGHTS

Weights in biblical times were carried in a bag or a satchel (Deut. 25:13; Prov. 16:11; Mic. 6:11) and were stones, usually carved into various animal shapes for easy identification. Their side or flat bottom was inscribed with the associated weight and unit of measurement. Thousands of historical artifacts, which differ by significant amounts, have been discovered by archaeologists and thus have greatly complicated the work of determining accurate modern-day equivalents.

Beka. Approximately 1⁄5 ounce, or 5.6 grams. Equivalent to 10 gerahs or ½ the sanctuary shekel (Exod. 38:26). Used to measure metals and goods such as gold (Gen. 24:22).

Gerah. 1⁄50 ounce, or 0.56 grams. Equivalent to 1⁄10 beka, 1⁄20 shekel (Exod. 30:13; Lev. 27:25).

Litra. Approximately 12 ounces, or 340 grams. A Roman measure of weight. Used only twice in the NT (John 12:3; 19:39). The precursor to the modern British pound.

Mina. Approximately 1¼ pounds, or 0.56 kilograms. Equivalent to 50 shekels. Used to weigh gold (1 Kings 10:17; Ezra 2:69), silver (Neh. 7:71–72), and other goods. The prophet Ezekiel redefined the proper weight: “The shekel is to consist of twenty gerahs. Twenty shekels plus twenty-five shekels plus fifteen shekels equal one mina” (Ezek. 45:12). Before this redefinition, there were arguably 50 shekels per mina. In Jesus’ parable of the servants, he describes the master entrusting to his three servants varying amounts—10 minas, 5 minas, 1 mina—implying a monetary value (Luke 19:11–24), probably of either silver or gold. One mina was equivalent to approximately three months’ wages for a laborer.

Pim. Approximately 1⁄3 ounce, or 9.3 grams. Equivalent to 2⁄3 shekel. Referenced only once in the Scriptures (1 Sam. 13:21).

Shekel. Approximately 2⁄5 ounce, or 11 grams. Equivalent to approximately 2 bekas. The shekel is the basic unit of weight measurement in Israelite history, though its actual weight varied significantly at different historical points. Examples include the “royal shekel” (2 Sam. 14:26), the “common shekel” (2 Kings 7:1), and the “sanctuary shekel,” which was equivalent to 20 gerahs (e.g., Exod. 30:13; Lev. 27:25; Num. 3:47). Because it was used to weigh out silver or gold, the shekel also functioned as a common monetary unit in the NT world.

Silver shekels minted by the Jews during the first revolt against the Romans (AD 66–73)

Talent. Approximately 75 pounds, or 34 kilograms. Equivalent to approximately 60 minas. Various metals were weighed using talents: gold (Exod. 25:39; 37:24; 1 Chron. 20:2), silver (Exod. 38:27; 1 Kings 20:39; 2 Kings 5:22), and bronze (Exod. 38:29). This probably is derived from the weight of a load that a man could carry.

Table 12. Biblical Weights and Measures and Their Modern Equivalents

| Hebrew/Greek Weights | Biblical Equivalent | US Equivalent | Metric Equivalent |

| Beka | 10 gerahs; ½ shekel | 1⁄5 ounce | 5.6 grams |

| Gerah | 1⁄10 beka; 1⁄20 shekel | 1⁄50 ounce | 0.56 grams |

| Litra | 12 ounces | 340 grams | |

| Mina | 50 shekels | 1¼ pounds | 0.56 kilograms |

| Pim | 2⁄3 shekel | 1⁄3 ounce | 9.3 grams |

| Shekel | 2 bekas; 20 gerahs | 2⁄5 ounce | 11 grams |

| Talent | 60 minas | 75 pounds | 34 kilograms |

| Linear Measurements | |||

| Cubit | 6 handbreadths | 18 inches | 45.7 centimeters |

| Day’s journey | 20–25 miles | 32–40 kilometers | |

| Fingerbreadth | ¼ handbreadth | ¾ inch | 1.9 centimeters |

| Handbreadth | 1⁄6 cubit | 3 inches | 7.6 centimeters |

| Milion | 1 mile | 1.6 kilometers | |

| Orguia | 1⁄100 stadion | 5 feet 11 inches | 1.8 meters |

| Reed/rod | 108 inches | 274 centimeters | |

| Sabbath day’s journey | 2,000 cubits | ¾ mile | 1.2 kilometers |

| Span | 3 handbreadths | 9 inches | 22.8 centimeters |

| Stadion | 100 orguiai | 607 feet | 185 meters |

| Capacity | |||

| Cab | 1 omer | ½ gallon | 1.9 liters |

| Choinix | ¼ gallon | 0.9 liters | |

| Cor | 1 homer; 10 ephahs | 6 bushels; 48.4 gallons | 183 liters |

| Ephah | 10 omers; 1⁄10 homer | 3⁄5 bushel; 6 gallons | 22.7 liters |

| Homer | 10 ephahs; 1 cor | 6 bushels; 48.4 gallons | 183 liters |

| Koros | 10 bushels; 95 gallons | 360 liters | |

| Omer | 1⁄10 ephah; 1⁄100 homer | 2 quarts | 1.9 liters |

| Saton | 1 seah | 7 quarts | 6.6 liters |

| Seah | 1⁄3 ephah; 1 saton | 7 quarts | 6.6 liters |

| Liquid Volume | |||

| Bath | 1 ephah | 6 gallons | 22.7 liters |

| Batos | 8 gallons | 30.3 liters | |

| Hin | 1⁄6 bath; 12 logs | 1 gallon; 4 quarts | 3.8 liters |

| Log | 1⁄72 bath; 1⁄12 hin | 1⁄3 quart | 0.3 liters |

| Metretes | 10 gallons | 37.8 liters | |

LINEAR MEASUREMENTS

Linear measurements were based upon readily available natural measurements such as the distance between the elbow and the hand or between the thumb and the little finger. While convenient, this method of measurement gave rise to significant inconsistencies.

Cubit. Approximately 18 inches, or 45.7 centimeters. Equivalent to 6 handbreadths. The standard biblical measure of linear distance, as the shekel is the standard measurement of weight. The distance from the elbow to the outstretched fingertip. Used to describe height, width, length (Exod. 25:10), distance (John 21:8), and depth (Gen. 7:20). Use of the cubit is ancient. For simple and approximate conversion into modern units, divide the number of cubits in half for meters, then multiply the number of meters by 3 to arrive at feet.

1 cubit = 2 spans = 6 handbreadths = 24 fingerbreadths

Day’s journey. An approximate measure of distance equivalent to about 20–25 miles, or 32–40 kilometers. Several passages reference a single or multiple days’ journey as a description of the distance traveled or the distance between two points: “a day’s journey” (Num. 11:31; 1 Kings 19:4), “a three-day journey” (Gen. 30:36; Exod. 3:18; 8:27; Jon. 3:3), “seven days” (Gen. 31:23), and “eleven days” (Deut. 1:2). After visiting Jerusalem for Passover, Jesus’ parents journeyed for a day (Luke 2:44) before realizing that he was not with them.

Fingerbreadth. The width of the finger, or ¼ of a handbreadth, approximately ¾ inch, or 1.9 centimeters. The fingerbreadth was the beginning building block of the biblical metrological system for linear measurements. Used only once in the Scriptures, to describe the bronze pillars (Jer. 52:21).

Handbreadth. Approximately 3 inches, or 7.6 centimeters. Equivalent to 1/6 cubit, or four fingerbreadths. Probably the width at the base of the four fingers. A short measure of length, thus compared to a human’s brief life (Ps. 39:5). Also the width of the rim on the bread table (Exod. 25:25) and the thickness of the bronze Sea (1 Kings 7:26).

Milion. Translated “mile” in Matt. 5:41. Greek transliteration of Roman measurement mille passuum, “a thousand paces.”

Orguia. Approximately 5 feet 11 inches, or 1.8 meters. Also translated as “fathom.” A Greek unit of measurement. Probably the distance between outstretched fingertip to fingertip. Used to measure the depth of water (Acts 27:28).

Reed/rod. Approximately 108 inches, or 274 centimeters. This is also a general term for a measuring device rather than a specific linear distance (Ezek. 40:3, 5; 42:16–19; Rev. 11:1; 21:15).

Sabbath day’s journey. Approximately ¾ mile, or 1.2 kilometers (Acts 1:12). About 2,000 cubits.

Span. Approximately 9 inches, or 22.8 centimeters. Equivalent to three handbreadths, and ½ cubit. The distance from outstretched thumb tip to little-finger tip. The length and width of the priest’s breastpiece (Exod. 28:16).

Stadion. Approximately 607 feet, or 185 meters. Equivalent to 100 orguiai. Used in the measurement of large distances (Matt. 14:24; Luke 24:13; John 6:19; 11:18; Rev. 14:20; 21:16).

LAND AREA

Seed. The size of a piece of land could also be measured on the basis of how much seed was required to plant that field (Lev. 27:16; 1 Kings 18:32).

Yoke. Fields and lands were measured using logical, available means. In biblical times, this meant the amount of land a pair of yoked animals could plow in one day (1 Sam. 14:14; Isa. 5:10).

CAPACITY

Cab. Approximately ½ gallon, or 1.9 liters. Equivalent to 1 omer. Mentioned only once in the Scriptures, during the siege of Samaria (2 Kings 6:25).

Choinix. Approximately ¼ gallon, or 0.9 liters. A Greek measurement, mentioned only once in Scripture (Rev. 6:6).

Cor. Approximately 6 bushels (48.4 gallons, or 183 liters). Equal to the homer, and to 10 ephahs. Used for measuring dry volumes, particularly of flour and grains (1 Kings 4:22; 1 Kings 5:11; 2 Chron. 2:10; 27:5; Ezra 7:22). In the LXX, cor is also a measure of liquid volume, particularly oil (1 Kings 5:11; 2 Chron. 2:10; Ezra 45:14).

Ephah. Approximately 3⁄5 bushel (6 gallons, or 22.7 liters). Equivalent to 10 omers, or 1⁄10 homer. Used for measuring flour and grains (e.g., Exod. 29:40; Lev. 6:20). Isaiah prophesied a day of reduced agricultural yield, when a homer of seed would produce only an ephah of grain (Isa. 5:10). The ephah was equal in size to the bath (Ezek. 45:11), which typically was used for liquid measurements.

Homer. Approximately 6 bushels (48.4 gallons, or 183 liters). Equivalent to 1 cor, or 10 ephahs. Used for measuring dry volumes, particularly of various grains (Lev. 27:16; Isa. 5:10; Ezek. 45:11, 13–14; Hos. 3:2). This is probably a natural measure of the load that a donkey can carry, in the range of 90 kilograms. There may have existed a direct link between capacity and monetary value, given Lev. 27:16: “fifty shekels of silver to a homer of barley seed.” A logical deduction of capacity and cost based on known equivalences might look something like this:

1 homer = 1 mina; 1 ephah = 5 shekels; 1 omer = 1 beka

Koros. Approximately 10 bushels (95 gallons, or 360 liters). A Greek measure of grain (Luke 16:7).

Omer. Approximately 2 quarts, or 1.9 liters. Equivalent to 1⁄10 ephah, 1⁄100 homer (Ezek. 45:11). Used by Israel in the measurement and collection of manna in the wilderness (Exod. 16:16–36) and thus roughly equivalent to a person’s daily food ration.

Saton. Approximately 7 quarts, or 6.6 liters. Equivalent to 1 seah. The measurement of flour in Jesus’ parable of the kingdom of heaven (Matt. 13:33; Luke 13:21).

Seah. Approximately 7 quarts, or 6.6 liters. Equivalent to 1⁄3 ephah, or 1 saton. Used to measure flour, grain, seed, and other various dry goods (e.g., 2 Kings 7:1; 1 Sam. 25:18).

LIQUID VOLUME

Bath. Approximately 6 gallons, or 22.7 liters. Equivalent to 1 ephah, which typically was used for measurements of dry capacity. Used in the measurement of water (1 Kings 7:26), oil (1 Kings 5:11), and wine (2 Chron. 2:10; Isa. 5:10).

Batos. Approximately 8 gallons, or 30.3 liters. A Greek transliteration of the Hebrew word bath (see above). A measure of oil (Luke 16:6).

Hin. Approximately 4 quarts (1 gallon, or 3.8 liters). Equivalent to 1⁄6 bath and 12 logs. Used in the measurement of water (Ezek. 4:11), oil (Ezek. 46:5), and wine (Num. 28:14).

Log. Approximately 1⁄3 quart, or 0.3 liter. Equivalent to 1⁄72 bath and 1⁄12 hin. Mentioned five times in Scripture, specifically used to measure oil (Lev. 14:10–24).

Metretes. Approximately 10 gallons, or 37.8 liters. Used in the measurement of water at the wedding feast (John 2:6).

Welfare Programs Governmental agencies established to distribute money, vouchers, medical coverage, and other necessities to those who are in need and who qualify for such distributions according to government-established rubrics. Welfare programs as we know them in our own modern societies are modern creations of secular states and are not aspects of the biblical or ancient Near Eastern world. The Bible, however, significantly addresses the complex subject of poverty and Israel’s responsibility to the poor.

The OT emphasizes Israel’s responsibility for the poor, especially fellow Israelites, but also foreigners sojourning in Israel (Exod. 22:25; Lev. 25:25, 35; Ruth 2:10). Because of the blessings bestowed on them by God, Israelites were commanded to be personally generous to those in need (Lev. 25:36–38; Deut. 15:7–13). They were to underharvest their fields, vineyards, and groves so that the poor might glean from them (Lev. 19:9–10; Deut. 24:19–22; Ruth 2:2–3, 7–11). Those who aided the poor were promised blessing (Prov. 19:17; 22:9; 28:27).

The powerful were not to oppress the poor by lending to them usuriously (Lev. 25:36–38) or enslaving them indefinitely (Lev. 25:39–42; Deut. 15:12; 24:14–15). Oppression was a grave offense because God had led Israel out from oppression in Egypt (Exod. 22:21; 22:9; Ps. 72:4, 12–14; Prov. 22:16; Jer. 22:17–19; Ezek. 18:5–9; 22:29–31; Amos 4:1–3).

Particularly in Proverbs, Israel is also cautioned against behaviors that lead to poverty, including sloth (6:6), slacking (10:4), neglecting discipline (13:18; 20:13), loving sleep (20:13), loving pleasure (21:17), heavy drinking and gluttony (23:21), and empty pursuits (28:19).

The NT builds and expands on the OT’s admonitions about treatment of the poor. Giving to the poor remains an imperative (Acts 2:45; Rom. 12:13; James 2:15; 1 John 3:17), but it is to be done without fanfare (Matt. 6:2–3; Mark 12:38–40). Generosity ought to be from the heart and regardless of means (Luke 21:2–4; 2 Cor. 8:1–5), yet not under compulsion (2 Cor. 8:8–9; 9:7). Christians are called to assume responsibility for themselves (2 Cor. 11:9; Eph. 4:28; 2 Thess. 3:7–11) and their families (1 Tim. 5:8, 16).

Well Unlike a spring, a well allows access to subterranean water through a shaft that has been dug into the ground. Wells typically were deep and lined with stone or baked brick for stability, often capped with heavy stone to prevent exploitation. In an arid environment, wells were invaluable to the community. Here, livestock were watered and conversations were held (Gen. 24:10–27; 29:1–14; John 4:6–8). Figuratively, the well is used of a lover (Song 4:15), an adulteress (Prov. 23:27), and a city (Jer. 6:7). Wells commonly were named (Gen. 21:25–31 [Beersheba, “well of an oath”]) and often fought over (Gen. 21:25–30; 26:18).

Three kinds of “well encounters” can be seen in Scripture: (1) human being with deity (Gen. 16:7–14), (2) clan with clan (26:20), and (3) man with woman (29:1–14). The latter became highly developed as a betrothal-type scene that included standard elements: stranger’s arrival (= otherness), meeting (= bond), paternal announcement (= hospitality), and domestic invitation (= acceptance) (see Rebekah [Gen. 24]; Jacob and Rachel [Gen. 29:1–14]; Moses and Zipporah [Exod. 2:15–22]).

Jesus’ encounter with the Samaritan woman (John 4:1–42) draws on multiple aspects of a well encounter: divine (Jesus) with human (the woman), Jew and Samaritan, a traveler, foreign (i.e., hostile) land, refreshment, announcement, invitation, and so on. However, now Jacob’s well (4:6) hosts Jesus’ presentation of himself as the groom whom she has been seeking (4:26). The patriarch’s well becomes a symbol of salvation, just as water becomes a metaphor for transformation (4:14–15). What could have been another “well of nationality” conflict (John 4:9, 11–12 [cf. Gen. 26:20: “Esek = argument”]) was elevated to a “living water” conversion (John 4:10, 13–15 [cf. Gen. 16:14: “Beer Lahai Roi = well of the Living One who sees me”]). Her plea “Come, see a man” (John 4:29) echoes an earlier “outcast,” Hagar, who exclaimed, “I have now seen the One who sees me” (Gen. 16:13).

West See Directions.

Whale The word “whale” occurs four times in the KJV. The KJV uses the word to describe the large fish that were created by God (Gen. 1:21). Similarly, the KJV, translating Jesus’ saying about Jonah, places the reluctant prophet in the “whale’s belly” (Matt. 12:40). This is the text that gives rise to the story of Jonah being swallowed by a whale, even though in Jon. 1:17 the KJV says that Jonah was swallowed not by a “whale,” but rather by a “great fish.” Finally, the KJV chooses “whale” for Job 7:12 and Ezek. 32:2, where in both cases a mythological sea monster is being described. In all these cases, more-recent versions prefer expressions such as “huge fish,” “sea monster,” and so on, depending on the context.

Wheat Wheat was a major crop in Palestine throughout biblical times and was the most important crop during the patriarchal times (Gen. 30:14). Wheat is a winter crop that was sown by hand in November or December; it was ready for harvest in May and was commemorated by the Festival of Weeks. Between the time of the late monarchy and the time of the NT, wheat was not only a food source but also a source of export income (Amos 8:5). Wheat can be eaten in a variety of ways and was often used, ground into fine flour, as an offering at the tabernacle and temple (Lev. 2:1). In the NT, wheat is used to symbolize the good produce of the kingdom of God (Matt. 13:24–31; cf. 3:12).

A field of wheat in Judea

Wheel There is no mention of wheels in the NT, while four different types of wheels are described in the OT. They include a potter’s wheel, a chariot wheel, a wheel used for processing grain, and the wheel referred to in Ezekiel’s theophany. The potter’s wheel was a simple device for creating pottery that was symmetrical and strong. Jeremiah observed a potter working with a pottery wheel (Jer. 18:3). Chariot wheels may have been invented by the Sumerians and were a common part of warfare during most of the OT. These wheels were either a solid wheel made of two or three planks of wood held together with wooden pegs or the more common wheel-and-spoke assembly. The spoke assembly was favored as iron and other metal technology was developed (Exod. 14:25). This sort of wheel also functioned in the temple to hold the lavers (1 Kings 7:30–33). Wheels also were used to crush grain in order to separate the husk from the harvested grain, to grind grain into flour, and to extract oil from olives (Isa. 28:28). There is much speculation about the specifications of the phantasmagorical wheels in Ezekiel’s visions, which include the enigmatic description of a wheel intersecting a wheel (Ezek. 1:15–16). It is clear from this description that the wheels are intended to guide a vehicle that can go in any direction instantly, but nothing else is known about them.

Whirlwind Elijah the prophet, at the end of his earthly career, was taken up alive into heaven in a whirlwind (2 Kings 2:11). The Hebrew word there behind “whirlwind” (se’arah) also describes the atmospheric phenomenon of Ezek. 1:4, the “windstorm”—the early impression the prophet had of the flying chariot cherubim, above which God was enthroned. Thus, God communicates in a special way to these two prophets in the whirlwind/windstorm; in both cases, this encounter initiated a climactic event in their prophetic ministries: Elijah’s ended, and Ezekiel’s began. The same Hebrew word is used when God speaks to Job: “Then the LORD answered Job out of the whirlwind [se’arah]” (Job 38:1; 40:6 NRSV [NIV: “storm”]). God appears at times in wind and storm (e.g., Ps. 77:18; Isa. 66:15; Jer. 23:19; Nah. 1:3).

White Typically associated with glory (Dan. 7:9; Matt. 17:2; Rev. 1:14) and purity (Ps. 51:7; Isa. 1:18; Rev. 3:4), white is a color worn by both angels (Mark 16:2; John 20:12; Acts 1:10) and heavenly saints (Rev. 7:9). On skin, however, white is abnormal, indicating a skin disease (Exod. 4:6; Lev. 13:3–4). Snow is often used in similes or comparisons to depict the color white (Exod. 4:6; Num. 12:10; 2 Kings 5:27; Ps. 51:7; Isa. 1:18; Dan. 7:9; Matt. 28:3; Rev. 1:14). See also Colors.

Whore See Prostitution.

Widow Lacking the provision and protection of a husband, widows are needy members of society, often grouped with the fatherless. Both Testaments promote special efforts to care for the needs of widows.

God’s concern for widows is evident in descriptions of his character and his commands for their protection and benefit. These are complemented by condemnations, punishments, and curses for those who fail to care for widows and by praise and blessings for those who do. Widows figure prominently in several biblical stories.

God himself cares for widows and gives them justice (Deut. 10:18; Ps. 68:5; Prov. 15:25). He instructs Israel and the church to care for widows. Negative commands warn of the consequences of mistreating widows (Exod. 22:22–24; Deut. 24:17–18). Positive commands require giving justice to widows (Isa. 1:17; Jer. 22:3), including them in community celebrations (Deut. 16:11–14), and providing for them. OT provision came in two forms. Every third year a harvest tithe was deposited in town to provide for the Levites, aliens, orphans, and widows (Deut. 14:27–29; 26:12–13). Additionally, harvesters were instructed to leave harvest remains for the alien (a displaced person seeking refuge), orphan, and widow (Deut. 24:17–22; cf. Ruth 2). Care for widows was central to the controversy that led to the appointment of deacons (Acts 6:1–6). Paul instructs Timothy to prioritize caring for widows who are over sixty years of age and without family to care for them (1 Tim. 5:1–16).

Failure to care for widows draws condemnation (Deut. 27:19; Job 24:2–3; Isa. 1:23; 10:2; Mal. 3:5; Mark 12:40). In contrast, care for widows is a mark of righteousness that brings blessing (Job 29:12–16; Jer. 7:5–7; Acts 9:39). James includes care for widows and orphans among the essential parts in his summary of true religion (James 1:27).

The OT included a special custom for the protection of, presumably, young widows. If a woman’s husband died and left her childless, her brother-in-law was to marry her and reckon the first child of the union as that of his deceased brother (Gen. 38:8; Deut. 25:5–6; Ruth 4:5, 10; Matt. 22:24). This custom lay behind the contention between Judah and Tamar (Gen. 38).

Widows figure prominently in several stories. A widow cared for Elijah in Zarephath (1 Kings 17; cf. Luke 4:25–26). At Elisha’s instruction, a widow was able to fill multiple containers with oil from a single jar (2 Kings 4:1–7). Jesus brought the son of a widow back to life (Luke 7:12–17). He remarked on a widow who made a small yet significant contribution to the temple treasury (21:1–4). Jesus illustrated persistence in prayer with a story about a widow seeking justice (18:1–8). See also Poor, Orphan, Widow.

Wife See Family; Marriage; Woman.

Wilderness A broad designation for certain regions in Israel, typically rocky, although also plains, with little rainfall. These areas generally are uninhabited, and most often “wilderness” refers to specific regions surrounding inhabited Israel. A fair amount of Scripture’s focus with respect to the wilderness concerns Israel’s forty-year period of wandering in the wilderness after the exodus (see also Wilderness Wandering).

GEOGRAPHY

More specifically, the geographical locations designated “wilderness” fall into four basic categories: the Negev (south), Transjordan (east), Judean (eastern slope of Judean mountains), and Sinai (southwest).

The Negev makes up a fair amount of Israel’s southern kingdom, Judah. It is very rocky and also includes plateaus and wadis, which are dry riverbeds that can bloom after rains. Its most important city is Beersheba (see Gen. 21:14, 22–34), which often designates Israel’s southernmost border, as in the expression “from Dan to Beersheba” (e.g., 2 Sam. 17:11).

Transjordan pertains to the area east of the Jordan River, the area through which the Israelites had to pass before crossing the Jordan on their way from Mount Sinai to Canaan. (Israel was denied direct passage to Canaan by the Edomites and Amorites [see Num. 20:14–21; 21:21–26]). Even though this region lay outside the promised land of Canaan, it was settled by the tribes of Reuben, Gad, and the half-tribe of Manasseh after they had fulfilled God’s command to fight alongside the other tribes in conquering Canaan (Num. 32:1–42; Josh. 13:8; 22:1–34).

The Judean Desert is located on the eastern slopes of the Judean mountains, toward the Dead Sea. David fled there for refuge from Saul (1 Sam. 21–23). It was also in this area that Jesus was tempted (Luke 4:1–13).

The Sinai Desert is a large peninsula, with the modern-day Gulf of Suez to the west and the Gulf of Aqaba to the east. In the ancient Near Eastern world, both bodies of water often were referred to as the “Red Sea,” which is the larger sea to the south. In addition to the region traditionally believed to contain the location of Mount Sinai (its exact location is unknown), the Sinai Desert is further subdivided into other areas known to readers of the OT: Desert of Zin (northeast, contains Kadesh Barnea), Desert of Shur (northwest, near Egypt), Desert of Paran (central).

The Judean wilderness

WILDERNESS IN THE BIBLE

Wilderness is commonly mentioned in the Bible, and although it certainly can have neutral connotations (i.e., simply describing a location), the uninhabited places often entail both positive (e.g., as a place of solitude) and negative (e.g., as a place of wrath) connotations, both in their actual geological properties and as metaphors. The very rugged and uninhabited nature of the wilderness easily lent itself to being a place of death (e.g., Deut. 8:15; Ps. 107:4–5; Jer. 2:6). It was also a place associated with Israel’s rebellions and struggles with other nations. Upon leaving Egypt, Israel spent forty years wandering the wilderness before entering Canaan, encountering numerous military conflicts along the way. This forty-year period was occasioned by a mass rebellion (Num. 14), hence casting a necessarily dark cloud over that entire period, and no doubt firming up subsequent negative connotations of “wilderness.” Similarly, “wilderness” connotes notions of exile from Israel, as seen in the ritual of the scapegoat (lit., “goat of removal” [see Lev. 16]). On the Day of Atonement, one goat was sacrificed to atone for the people’s sin, and another was sent off, likewise to atone for sin. The scapegoat was released into the desert, where it would encounter certain death, either by succumbing to the climate or through wild animals.

On the other hand, it is precisely in this uninhabited land that God also showed his faithfulness to his people, despite their prolonged punishment. He miraculously supplied bread (manna) and meat (quail) (Exod. 16; Num. 11), as well as water (Exod. 15:22–27; 17:1–7; Num. 20:1–13; 21:16–20). God’s care for Israel is amply summarized in Deut. 1:30–31: “The LORD your God, who is going before you, will fight for you, as he did for you in Egypt, before your very eyes, and in the wilderness. There you saw how the LORD your God carried you, as a father carries his son, all the way you went until you reached this place.”

The harsh realities of the wilderness also made it an ideal place to seek sanctuary and protection. David fled from Saul to the wilderness, the Desert of Ziph (1 Sam. 23:14; 26:2–3; cf. Ps. 55:7). Similarly, Jeremiah sought a retreat in the desert from sinful Israel (Jer. 9:2).

Related somewhat to this last point is Jesus’ own attitude toward the wilderness. It was there that he retreated when he could no longer move about publicly (John 11:54). John the Baptist came from the wilderness announcing Jesus’ ministry (Matt. 3:1–3; Mark 1:2–4; Luke 3:2–6; John 1:23; cf. Isa. 40:3–5). It was also in the desert that Jesus went to be tempted but also overcame that temptation.

Wilderness Wandering In the biblical account of the exodus, Israel’s departure from Egypt begins in Exod. 12:37. The original intention was for the Israelites to go to Mount Sinai to receive the law and instructions for the tabernacle and then to proceed to Canaan. But Israel’s trip was not to be quite that simple. Because of the Israelites’ disobedience in the desert, they were condemned to a forty-year period of wilderness wandering, enough time for those twenty years of age or older during the rebellion to die in the wilderness (see Num. 14, which describes what is actually the final rebellion in a series of grumbling incidents that go back to Exod. 15:22–27).

Technically, the wilderness period began immediately after the crossing of the Red Sea. The Israelites passed through the Desert of Shur, the Desert of Sin, Rephidim, and then Sinai itself. These locations, however, were only stations on the way to Sinai, and so they do not pertain to the specific forty-year period of punishment, which begins in Num. 14. Their wandering period would not be officially over until they crossed the Jordan River and entered Canaan (Josh. 3:17).

MAPPING THE ROUTE

The wilderness wandering, like the exodus and the passage through the Red Sea, are very difficult to outline precisely from a geographical and archaeological point of view. Many of the places named in the lists have not been located. Moreover, the two itinerary lists, one in Num. 33 and the other at various points in Num. 11–22, do not agree on every point. Although the two lists do not directly conflict, Num. 33 includes many more sites than Num. 11–22 and leaves out relatively few. One reason for this difference may be that only Num. 33 is actually intended to be an itinerary, whereas the sites mentioned elsewhere in Numbers are injected in the course of a narrative.

What contributes to difficulties in locating the wilderness route is that biblical names are not those used today, not to mention that many of these places no longer exist at all. Moreover, similarities between some names then and now have no necessary bearing on the issue. Also, it seems that at least some of the biblical names are symbolic. For example, “Meribah” means “quarreling,” and “Massah” means “testing.” These names seem to reflect the events recorded in Exod. 17 rather than being original names.

One of the most contested issues concerning the wilderness wandering is where it began: the location of Mount Sinai. It is commonly accepted that this mountain is located somewhere in the Sinai Peninsula, although numerous places have been suggested. Best known, perhaps, is Jebel Musa, the location of St. Catherine’s monastery, located in the southern portion of the peninsula. This is based not so much on historical evidence, however, as on church tradition. Another theory puts Mount Sinai in the eastern portion of the peninsula, near Midian. One factor in favor of this theory is that Moses first met God on Mount Sinai when he was living in Midian (with Zipporah, his wife, and Jethro, his father-in-law). According to Exod. 3:1, Moses left Jethro’s house to tend his sheep and it was on this journey that he came to Mount Sinai for the first time. Unless one presumes that he herded the sheep over one hundred miles in a southwesterly direction, into the desert, one might conclude that Mount Sinai is perhaps a more reasonable distance from Midian. But as with all theories regarding Sinai’s location, conclusive evidence is lacking.

REMINDER OF REBELLION AND ITS CONSEQUENCES

Interest in the wilderness wanderings, however, extends beyond understanding ancient geography. There is also a powerful theological dimension, and this seems to be of greater importance for biblical writers. Wandering in the wilderness is Israel’s punishment for disobedience and rebellion. As such, it stands as a reminder for later Israelites to encourage them not to repeat that mistake. Indeed, the events of Numbers are not recounted merely to catalog arcane events but are preserved in writing to be a reminder for subsequent generations.

Israel’s wilderness experience is referenced in various portions of the OT. The rebellion is mentioned in Ps. 106:14, 26, and wilderness is associated with a place of death. Elsewhere the desert represents a place of God’s protection and provision for the new generation of Israelites living in the desert (Deut. 8:15–16; 29:5; 32:10; Ps. 136:16; Hos. 13:5).

Another example of a later appropriation of the wilderness tradition is found in Ps. 95, where the Israelites, perhaps in an exilic setting, are warned not to rebel as the exodus generation did (vv. 7–11). This same warning of Ps. 95 is picked up by the writer of Hebrews and applied to the church (Heb. 3:1–4:13). The author argues that since a greater mediator than Moses has come, the past warning holds all the more as the church goes through its period of wilderness wandering (which lasts until the church’s entrance into its heavenly promised land). The main difference Hebrews introduces is that the church’s period of wilderness wandering is not characterized by God’s wrath but rather is a time of God’s activity in redeeming the world.

Will, Human “Will” refers to a person’s wishes or desires and the power to act on those desires. In the Bible, human will is at times contrasted with God’s will or mercy (Rom. 9:16 ESV, NRSV; cf. John 1:13) or the power of the Holy Spirit (2 Pet. 1:21 NASB, NRSV). In his humanity, Jesus had his own will, but he chose to submit it to the Father’s will (Luke 22:42; John 6:38). See also Free Will; Will of God.

Will of God The accomplishment of God’s purposes. This was most clearly expressed by Jesus’ prayer, “Not my will, but yours be done” (Luke 22:42). Jesus stipulated in the Gospel of John that he was pursuing not his own will but that of God (5:19, 30; 6:38). God’s will is revealed in creation (Rev. 4:11), Scripture (2 Pet. 1:20–21), his standards (Ezra 10:11; Rom. 12:1–2; 1 Thess. 4:3), his calling (1 Cor. 1:1), and his purpose (Isa. 46:10).

Willow Shrubs or small trees with reddish branches that grow by brooks and watercourses (Job 40:22; Isa. 15:7 [NIV: “poplars”]). Several species are common in Palestine, the most common being the Palestine willow. This is the willow in Ezek. 17:5, and not the “weeping willow,” which was introduced into Palestine after the exile. The ease with which the willow (poplar) takes root from a twig is used figuratively in Ezek. 17:5 (cf. Isa. 44:4). Branches from the willow and other trees were taken to make booths at the Feast of Tabernacles (Lev. 23:40).

Willow Creek See Arabim.

Willows, Brook of; Willows, Wadi of See Arabim.

Wimple In Isa. 3:22 the KJV translates the Hebrew word mitpakhat as “wimple,” referring to a woman’s medieval head covering that framed her face. Other translations render the Hebrew word as “cloak” (NIV, NASB, NRSV). In Ruth 3:15 the KJV translates the same Hebrew word as “vail” (NIV: “shawl”).

Wind Scripture describes wind as a powerful force that is under God’s command. The Hebrew word ruakh sometimes is translated as “wind” but other times can mean “breath,” as well as “spirit” (Gen. 1:2). The Greek word for “spirit,” pneuma, hints of a similar range of meaning, although another word is most often used in the NT to denote wind.

Old Testament. Throughout the OT wind is used by God to fulfill his purposes. Psalm 148:8 declares that winds do God’s bidding. Yahweh keeps the wind in storehouses until they are needed (Ps. 135:7; Jer. 10:13). God uses wind to protect and provide for his people. For instance, God sends a wind over the earth to cause the floodwaters surrounding the ark to recede (Gen. 8:1), a strong east wind to drive back the sea during the exodus from Egypt (Exod. 14:21), and a wind that drives quail in from the sea to serve as food for the Israelites in the wilderness (Num. 11:31).

Wind can also be an agent of God’s destruction. God sends a plague upon Egypt by making an east wind blow locusts all across the land; afterward, God uses a west wind to blow the locusts into the sea (Exod. 10:13–19). In the book of Job a mighty wind from the desert causes the house of Job’s eldest son to collapse, killing Job’s seven sons and three daughters (Job 1:19). In the book of Jonah a great wind sent by God threatens to destroy Jonah’s ship, and a scorching east wind later causes Jonah to grow faint and desire death (Jon. 1:4; 4:8). The prophetic books use the subject of wind in communicating God’s judgment (e.g., Isa. 28:2; 64:6; Ezek. 5:2; 13:11).

While a single wind is able to blow in several directions (Eccles. 1:6), many passages specify four winds from the four quarters of the heavens. The north wind brings rain (Prov. 25:23), while the south wind brings heat (Job 37:17), both of which are useful for growing a garden (Song 4:16). Only one verse refers to the west wind specifically (Exod. 10:19), but numerous verses refer to the east wind as an agent of destruction, often appearing along with military terms. When let loose by God (Ps. 78:26), the east wind may shatter ships (Ps. 48:7), and those in its path will scatter (Jer. 18:17) or shrivel (Ezek. 19:12). In Hos. 12:1 God accuses Israel of pursuing the east wind along with multiplying lies and violence. Together, the four winds can be sent to bring destruction (Jer. 49:36) or to bring life (Ezek. 37:9). They also appear in the visions of Daniel (Dan. 7:2; 8:8; 11:4; cf. Rev. 7:1).

God rides on the wings of the wind on cherubim (Ps. 18:10; 2 Sam. 22:11), with the clouds as his chariot (Ps. 104:3). In Ps. 104:4 the winds are called God’s “messengers.” This imagery is strikingly similar to ancient descriptions of the Canaanite god Baal, although Scripture adds that it is Yahweh who created the wind (Job 28:25; Amos 4:13). Yahweh’s power is not contingent upon wind, as Elijah learns when he experiences the presence of Yahweh in the whisper and not the wind (or the earthquake) after his successful contest against the prophets of Baal (1 Kings 19:11–12).

The wisdom literature focuses upon other characteristics of wind besides its power. The transient nature of wind is significant, as wind is the inheritance of those who bring trouble upon their family (Prov. 11:29). Ecclesiastes continually refers to all things done under the sun as “a chasing after the wind” (e.g., 1:14, 17). Empty talk is spoken of as wind (Job 8:2). The function of wind to blow away chaff is also used to declare the fate of the wicked (e.g., Ps. 1:4; cf. Job 21:18). The unpredictability of wind serves as a metaphor for the mystery of God’s actions (Eccles. 11:5).

New Testament. In the NT, the Gospels reveal the divine nature of Jesus by emphasizing his ability to command the wind (Matt. 8:26–27). Jesus declares that the Son of Man will gather his elect from the four winds (Matt. 24:31; Mark 13:27). Wind is a metaphor in John 3:8 for the mystery and unpredictability of those born of the Spirit. Jesus uses the image of empty talk as wind when he refers to John the Baptist as a prophet rather than a reed swayed by the wind (Matt. 11:7; Luke 7:24). In Eph. 4:14 false teaching is referred to as wind. It is wind that easily sways the one who doubts (James 1:6). Finally, a correlation between wind and the Holy Spirit occurs when a sound like a violent wind occurs at the time when the Holy Spirit fills all those in the house at Pentecost (Acts 2:2).

Window In biblical times, windows usually were small and few, for the purpose of admitting light or air. Windows helped regulate temperatures inside a house. Some, however, were large enough to permit an intruder (Joel 2:9; cf. Jer. 9:21) or a fugitive (Josh. 2:15; 1 Sam. 19:12; 2 Cor. 11:33) to go through.

Windows of “recessed frames” in Solomon’s temple (1 Kings 6:4 NRSV), the numerous windows in Ezekiel’s eschatological temple (Ezek. 40:16, 22, 25, 29; 41:16), and the elaborately paneled windows in Jehoiakim’s house (Jer. 22:14) contrast the simplicity of general window design.

Symbolically, “windows of/in heaven” depict wide openings through which blessings or judgment flow to earth (Gen. 7:11; 8:2; 2 Kings 7:2, 19; Isa. 24:18 KJV [NIV: “floodgates of the heavens”]; cf. Mal. 3:10).

Wine An alcoholic beverage made primarily by fermenting grapes, wine was valued as both a pleasurable and a functional drink (Ps. 104:15; 1 Tim. 5:23) and therefore a staple of ceremonial practice and social gatherings (Exod. 29:40; John 2:1–3). For this reason, wine is a symbol of God’s blessing (Gen. 27:28; John 2:11), particularly for his covenant people (Isa. 25:6, 55:1; 1 Cor. 11:25). Yet the Bible also warns against the abuse of alcohol, which can lead to drunkenness and debauchery (Prov. 9:4–5; Eph. 5:18). Such abuse becomes a symbol of God’s curse for disobedience (Hos. 4:11; 9:2; Matt. 27:48–49).

A lagynos, a single-handled wine container, which would be hung in front of wine houses as a kind of shop sign

Winepress A mechanical device that extracts juice from grapes for use in making wine. Winepresses in ancient Israel were hewn from bedrock to form a flat surface for treading. They consisted of a pair of square or circular vats arranged at different levels and connected by a channel. The vat in which the grapes were trodden (gat) was higher and larger than its deeper counterpart (yeqeb) into which the juice flowed from the press. The beam press came later, a Greek invention dating to the sixth century BC. One end of the beam was secured to a wall, the other end weighted with stones, and the baskets of grapes placed beneath. Even after the invention of the beam press, however, treading the grapes under bare feet was preferred in both OT and NT times because of the quality of the product obtained.

The vintage season was a joyous occasion accompanied by celebrating, feasting, shouting, and rejoicing as family members trod the grapes. Thus, the imagery of a winepress overflowing with new wine often stands for divine blessing (Prov. 3:10; Joel 2:24), and the lack of new wine from a winepress is a picture of divine judgment (Job 24:11; Jer. 48:33; cf. Isa. 16:10). As a metaphor based upon the treading of the grapes in the vats, the winepress connotes divine destruction and judgment. In Joel 3:13 the image of God’s mighty army trampling the enemy is couched in the language of a vintner treading the grapes. The abundant flow from the presses is then compared to the greatness of the wickedness of the nations. Isaiah 63:3 likens a judging God to a lonely treader of a winepress, and the juice from the press to blood. This is best understood against the background that normally treading in vintage is communal work. The lonely treader conveys the idea that God is the only judge of the nations. The metaphor of the winepress for judgment is used climactically in Rev. 14:19–20; 19:15, where the winepress is identified with divine wrath and the juice with bloodshed. In Sir. 33:17, however, the winepress is used as a positive metaphor connoting the learning of Torah.

The winepress and wine occur in various places in the book of Judges, yet in each there is a literary twist. Gideon was introduced as threshing wheat in a winepress to hide it from the Midianites (6:11). Zeeb, the Midianite general, was killed at the winepress of Zeeb (7:25). Gideon calmed the anger of the Ephraimites by reference to Abiezrite wine (8:2). A vintage festival marked the beginning of the end for Abimelek (9:27). Finally, the kidnap of the women of Shiloh occurred during a vintage festival (21:20–22).

Wing Wings symbolize protection (Exod. 19:4; Ruth 2:12; Ps. 17:8; Matt. 23:37) or strength: “Those who hope in the LORD will renew their strength. They will soar on wings like eagles” (Isa. 40:31). In some cases, heavenly beings have wings (Ezek. 1:6–11; Rev. 4:8).

Winnowing Part of the process for preparing grain that follows harvesting and threshing. Farmers winnowed grain to separate grain from chaff (Ruth 3:2). They used a pitchfork (Jer. 15:7; Matt. 3:12 // Luke 3:17) to toss the grain and chaff into the air. The heavier grain fell into a pile, but wind blew the lighter chaff away. The term “winnow” is also often used for discerning judgment by God (Matt. 3:12) and by humans (Prov. 20:8; Isa. 41:15–16).

Winnowing Fork A tool resembling a shovel or a fork that was used in the winnowing process. The winnowing fork (KJV: “fan,” Isa. 30:24; Matt. 3:12; Luke 3:17) was used to throw the grain into the air to allow the chaff to blow away while the heavier grain settled. See also Winnowing.

Winter House The KJV uses the term “winter house” to refer both to a room set aside within a house that retained heat from a brazier or firepot containing hot coals (Jer. 36:22) and to an auxiliary winter residence (Amos 3:15). In modern versions such as the NIV, these are distinguished as “winter apartment” and “winter house.” Ornate auxiliary residences served kings (see 1 Kings 21:1) and the wealthy upper class, and in Amos 3:15 such opulence comes under God’s judgment as a sign of injustice against the poor.

Wisdom, Wise In the OT, wisdom (khokmah) is a characteristic of someone who attains a high degree of knowledge, technical skill, and experience in a particular domain. It refers to the ability that certain individuals have to use good judgment in running the affairs of state (Joseph in Gen. 41:33; David in 2 Sam. 14:20; Solomon in 1 Kings 3:9, 12, 28). It can also refer to the navigational skills that sailors use in maneuvering a ship through difficult waters (Ps. 107:27). Furthermore, wisdom includes the particular skills of an artisan (Exod. 31:6; 35:35; 1 Chron. 22:15–16). In all these cases, wisdom involves the expertise that a person acquires to accomplish a particular task. In these instances “wisdom” is an ethically neutral term, or at least that dimension is not emphasized. The wise are those who have mastered a certain skill set in their field of expertise.

The uniqueness of the OT wisdom literature (Job, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, etc.) is that it highlights the moral dimension of wisdom. Here “wisdom” refers to developing expertise in negotiating the complexities of life and managing those complexities in a morally responsible way that honors God and benefits both the community and the individual. Although it is difficult to pin down a concise definition, one can gain a better understanding of wisdom by investigating two important dimensions: wisdom as a worldview, and the traits of a person who is considered to be wise.

WISDOM AS WORLDVIEW

Wisdom describes a worldview, a particular way of perceiving God, humanity, and creation. The God of the sages is sovereign Lord. But their understanding of sovereignty manifests itself differently from the way the Torah and the prophets describe it. All through the OT Israel frequently witnessed God at work through mighty acts of deliverance and conquest and protection. God orchestrated these monumental saving acts. Wisdom, however, looks at God’s sovereignty differently. It makes few references to the mighty acts of God.

For the sage of Ecclesiastes, the world is the arena of God’s mystery. God is active in creation and in the world, but his ways are inscrutable (3:11; 6:10–12; 7:13–14). God is distant (5:2), but he spans this distance when humans receive and enjoy the ordinary gifts of friendship, food, family that he gives to sustain life (2:24–26; 3:12–13; 5:18–20; 9:7–10).

For the sage of Proverbs, God is present in the daily routines of life. God is involved in the interactions that take place between people (15:22; 27:5–6, 9–10, 17). God works through both the good and the bad experiences of life, employs human language to carry out his purposes, and uses material wealth and even poverty in the service of maturing people.

In the very realm where individuals believe that they exercise the most control—human thoughts and plans—God establishes a presence (Prov. 16:1, 9). Exactly how God does this the sage does not say; rather, the sage assumes that divine sovereignty and human activity exist together in inexplicable ways.

From the view of God to the view of humans, wisdom emphasizes a particular perspective. Wisdom’s worldview of humanity places great confidence in what humans can accomplish. Wisdom affirms that individuals are capable of making wise choices and displaying responsible behavior. In so doing, such people will live healthy, prosperous, successful lives (Prov. 9:1; 14:1, 11). Because they value human ability and understanding, the sages use all the resources at their disposal to discover the means of living a successful life. They use the sources of the culture around them as well as their own inner resources.

One other dimension to probe in wisdom’s worldview is the important role that creation plays. Living in harmony with the order of the universe brings longevity, wealth, and good fortune. When individuals integrate their lives with the order of creation, success results; neglecting that order brings failure. However, the sages sometimes are accused of possessing too mechanical a view of such order: the wise, it is said, believe in a world automatically programmed to prosper the pious and punish the perverse. Such a view perceives the world as operating on a rigid system of rewards and punishments. It is true that some wisdom teaching appears to reflect this worldview (Prov. 26:27). However, even though the sages developed plans and strategies by which to live, they did not believe in a created order that operated mechanically. The sages do have an interest in discovering certain predictable patterns of experiences, but the order that underlies the experiences of life is not a fate-producing one (21:30–31). The sages wrestle not so much with the concept of a rigid order as with the person of God. A dialectic exists between the predictable order of creation and the free work of God. Wisdom seeks not to master life but to navigate it. The sages guided themselves and others through the experiences of life, striving not to dominate but rather to assume responsibility. This is the fundamental worldview of wisdom.

TRAITS OF THE WISE