EXAM OBJECTIVES

Knowing your troubleshooting techniques

Communicating effectively and professionally

As a CompTIA A+ Certified Professional, you will often need to troubleshoot systems as well as deal with customers or clients. For you to complete these tasks, you need good troubleshooting skills, and you also need to develop good customer-relation skills.

This chapter examines the basics of troubleshooting. These basics are not centered on specific hardware components, but rather on basic methodology that is used to solve problems. This methodology will not change even though the underlying technology might change. Troubleshooting specific components is covered in Book 4, Chapter 2.

When solving problems for customers — internal or external customers — you will likely need to talk to them. This chapter takes a look at the communication skills that help you maintain a high level of professionalism.

Using Troubleshooting Procedures and Good Practices

Many people say that troubleshooting skills cannot be learned, but this is not true. If you are methodical or just curious, you will probably have an easier time troubleshooting. However, anyone can learn the practical order to follow when troubleshooting problems. Follow the steps in this chapter, and you should have an easy time when it comes to troubleshooting.

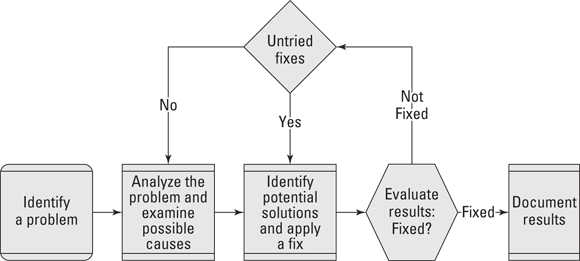

The two main sections of troubleshooting are hypothesis generation and hypothesis evaluation. In other words, based on the symptoms that you see, you create a list of things that might be wrong and then test to see whether any of them are actually the problem. Figure 2-1 shows a rough outline of general troubleshooting procedures.

CompTIA lays out its recommended troubleshooting process as follows, but remember to take any corporate policies into account when going through the process:

CompTIA lays out its recommended troubleshooting process as follows, but remember to take any corporate policies into account when going through the process:

- Identify the problem.

- Establish a theory of probable cause.

- Test the theory to determine cause.

- Establish a plan of action to resolve the problem and implement the solution.

- Verify full system functionality and if applicable implement preventive measures.

- Document findings, actions, and outcomes.

To troubleshoot any system, you need to know how that system is supposed to function and what options can be changed or might fail. This information allows you to quickly assemble a list of hypotheses. The better you know the system, the easier this phase will be. You then need to test these hypotheses. Testing might involve using tools appropriate to the system to test the condition of certain components, or it might involve changing a series of configuration settings and rechecking to see whether the problem has been resolved at certain stages.

Identifying the problem

The first task is to identify the problem. The first step to identifying the problem is to question the system’s user. This shouldn’t be a police interrogation, nor should you accuse the user of causing the error. You might discover, after all is said and done, that the user actually did cause the error, but you should never assume that upfront, or you will quickly become an adversary instead of an advocate.

The information you gather from the user helps you set the scope of the problem. Many users start with the simple, “It’s broken!” It is up to you to figure out how “it” is “broken,” and you do that by asking simple questions: “What issues are you having with it? What is it not doing? Does it always happen or only at certain times?”

Even if the user gives you a better starting point, you will likely still need to ask some questions to refine the scope of the problem. Here are some things to keep in mind while you try to identify the problem:

- Identify changes to the computer. Some errors are caused by the user or his surroundings. The user should always be asked up front, in much the same way a doctor asks whether his patient’s lifestyle has changed or whether he is on any medication. Ask the user whether he made any changes to the computer by installing software, changing hardware, or changing the computer’s location. This often provides you with an early lead to the possible problem.

- Break big problems into smaller pieces. Continuing with the doctor analogy (see the preceding bullet), the “I feel sick” statement causes a doctor to ask questions and build a list of symptoms. That list of symptoms (sore throat, headache, runny nose, gaping hole in abdomen) might be easier to deal with if broken down into groups of symptoms rather than being treated as a whole. The doctor might then treat each group of symptoms individually. The same applies to computer problems. That “broken” computer might be malfunctioning because of a variety of smaller problems: insufficient RAM, a fragmented hard drive, malware, Trojans, and poor networking protocol configuration. If the problems are broken down instead of being treated as a whole, you can approach each item separately.

-

Prioritize problems and decide in which order they should be tackled. With your list of problems, decide which are the most critical and should be approached first. For instance, if the hard drive is corrupted and you need to re-install or upgrade the operating system, fix the issue with the hard drive before performing the software upgrade.

In most cases, you prioritize the issues based on the impact to the user and the impact of other fixes implemented at a later time. One rule I live by is, “Fix the business problem first.” For example, if you are working for a stock trader, she needs her stock trading program working immediately, but she might be willing to wait for a fix to the word processing program.

In most cases, you prioritize the issues based on the impact to the user and the impact of other fixes implemented at a later time. One rule I live by is, “Fix the business problem first.” For example, if you are working for a stock trader, she needs her stock trading program working immediately, but she might be willing to wait for a fix to the word processing program.

Analyzing the problem and potential causes

For each problem you work on, decide the scope of the problem. This can be done by testing. The initial tests you conduct determine the scope of the problem. Say you go to a doctor for an upset stomach. She asks stomach- and food-related questions and then probably runs some basic tests to determine whether the problem is an ulcer, an allergy, or just some bad sushi.

The same is true with computer issues. You ask questions and then perform rudimentary tests to determine the scope of the issue. For example, after being told that a printer does not print, you might verify that its cables are in place, it powers up, it has toner or ink, and it accepts commands from the computer. These rudimentary checks allow you to see how large the problem is; from there, you can perform additional analyses. For example, if the printer is passing paper but the pages come out blank, your list of potential causes can be reduced because it is not a power issue. Rather, the problem is either with the transfer of the printing material — the ink or toner — or with the interpretation of the commands from the computer. With this narrowed list of potential causes, you can move on with addressing the problem.

The basic troubleshooting process

With your list of potential causes in hand, move on to figuring out potential solutions. In some instances, you might approach the problem starting at a general level and then work down to specific components. Conversely, you might look at entire systems, like the power system, in a sequential manner. In most cases, your potential causes can be placed on an imaginary line that forms a resolution path. The resolution path forms a sequential chain of possible causes for the issue, starting at one point and moving to another. For instance, if a computer does not power up, you can start testing at the electrical socket; move to the power supply, power supply connectors, power switch, motherboard; and then move to the devices. This process moves through the sequential chain along the possible path that power would flow. Following a possible resolution path from one end to the other is sometimes referred to as the layered or linear approach.

The term layered is often used when discussing networking issues because the layers in the networking model are easily definable and are often referenced. For more information about the layered network model, see Book 8, which discusses networking.

The term layered is often used when discussing networking issues because the layers in the networking model are easily definable and are often referenced. For more information about the layered network model, see Book 8, which discusses networking.

Most systems that make up computer systems and networks can be broken down into layered models, and troubleshooting can move through these layers. Another example of layered troubleshooting is a gasoline engine, with its two major systems: the electrical system and a fuel supply system. The electrical system has layered troubleshooting starting at a power source (say, a battery) through power supply cables, a distributor, and finally to a spark plug. The fuel supply system starts with fuel storage, supply lines, a pump, and filter, and then ends at a combustion chamber. In the event of a problem, both systems can be reviewed and tested from end to end, in a linear or layered manner, until the problem is located.

The following sections take a close look at some suggestions for implementing potential solutions.

Back up any settings or files you need to change

You don’t want to introduce more problems to a system than it had when you started. Before changing any basic input-output system (BIOS) or application settings, record the original settings — or back them up. For instance, if an application that you are troubleshooting stores its configuration in a text or binary file, copy that file so you can quickly restore it to the initial state if your solution doesn’t work.

Some computers allow you to make a backup copy of your BIOS settings, which are stored in complementary metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS) memory; or back up the existing BIOS prior to overwriting it with an upgrade. Some things cannot easily be reversed, like the application of a Service Pack, so care should be taken when doing those tasks, such as setting a restore point or making a full system backup.

If you need to make a large number of changes, it is a good idea to take a complete backup of the computer prior to starting your troubleshooting process so that you will be able to retrieve any settings or files that are deleted or modified.

If you need to make a large number of changes, it is a good idea to take a complete backup of the computer prior to starting your troubleshooting process so that you will be able to retrieve any settings or files that are deleted or modified.

Test one configuration change at a time

This step is required to know what the fix actually is. If you change five things and the problem component now works, you don’t know which change made the difference. In some cases, you might incur monetary costs. For instance, if the computer starts to blue screen on boot and you suspect a hardware fault, you could change the disk controller, hard drive, RAM, CPU, and power supply. After that, if the problem no longer exists, what was the solution? Are you going to replace all five components the next time you have the issue? By substituting one item at a time and testing at each step to re-create the issue, you will know which change you implemented corrected the problem.

Question the obvious

When I get the messages Missing Operating System, NTLDR is missing, BOOTMGR is missing, or messages related to winload.exe or BCD not being found, the first thing I do is look for a floppy disk or USB drive that was left plugged into the system. For power problems, is it plugged in? For network problems, is the cable plugged into the correct jack? These simple first steps are often overlooked by the user. Just because it is obvious to you does not mean it is obvious to the user. If the solution is not obvious, go back to your layered approach — it will not let you down.

Research to find potential fixes

If you run out of ideas for a specific problem, do a little research. The “Documentation resources” sidebar, later in this chapter, gives you some ideas about where to begin.

There is nothing wrong with you, as a CompTIA A+ Certified Professional, not knowing the solution to a particular issue with a specific product. What is important is that you know where you can find the answers — quickly.

There is nothing wrong with you, as a CompTIA A+ Certified Professional, not knowing the solution to a particular issue with a specific product. What is important is that you know where you can find the answers — quickly.

Prioritize potential fixes for the problem

After you spent time researching the symptoms, now you have a long list of items to check and possible solutions to apply, and you must prioritize them. You can put the most-likely fix at the top of your list, or you can put the quickest and least-disruptive fix at the beginning of the list. In most cases, you will likely do the latter.

For instance, a good fix for many software-related problems is to reimage the computer or re-install the application. Although this often fixes the problem, it can be time consuming for you and disruptive for the user. Re-installation often involves checking for local files that need to be backed up, backing them up, verifying application settings, restoring the computer operating system, restoring backed-up user files, and reapplying settings. This usually leaves a lot of settings that the user needs to reset when she runs the application(s) for the first time after re-installation. Because this is time consuming and disruptive, it should be left toward the end of the list of options. Rather, the list should begin with items such as verifying application settings, testing new-user profiles, and applying other quicker and less-disruptive fixes.

Test related components

Sometimes, a symptom in one area is caused by a problem in another. The classic example with computers is being asked to look at a computer that is reported as slow, and has an extremely active hard drive. You can test the hard drive and related cables, use diagnostic utilities to test its health, swap it with another, only to not find a solution. Then you have to take a step back and evaluate other system components, such as memory. In many cases, a lack of RAM can cause excessive paging, which causes high disk activity, so the solution to the problem might be to add RAM to the computer and not do anything with the hard drive. If you did not look at the related component (RAM), you would not have been able to solve the problem with the active hard drive. In some cases, you might need to do some research to know what components of the system are related. Don’t just go for the obvious: Test related systems as well. That might be where the actual issue is.

Call in the “big guns”

You are not alone in this exercise. In many cases, there may be internal resources to which you may escalate a problem that you cannot resolve. If there are no internal resources above you, then in many cases there is a vendor or manufacturer that you may be able to contact. Many vendor support departments have seen your problem and can offer steps to resolve the issue. Never be afraid to realize your limits and ask for help when you need it.

You are not alone in this exercise. In many cases, there may be internal resources to which you may escalate a problem that you cannot resolve. If there are no internal resources above you, then in many cases there is a vendor or manufacturer that you may be able to contact. Many vendor support departments have seen your problem and can offer steps to resolve the issue. Never be afraid to realize your limits and ask for help when you need it.

Evaluating results

At each step of the analysis and application of potential fixes, evaluate the results. By evaluating often, you will know what is working, what is not, and what additional problem you might have caused. At any time, the results might cause you to change your initial hypothesis and choose to pursue a different path. Changing your hypothesis should be done only if there is sufficient proof that your initial statements were in error, or you might find yourself running in circles.

Once you have identified the source of the problem, there may be repair options available to the customer. Make sure you present the pros and cons of each available option so that the customer can make an informed decision. In some cases, repair may not be the most cost-effective solution.

Going the extra mile

Once you have found the problem, resolved it, and verified that the system is back in full operation, what else can you do? Well, if that problem was a result of user error or malicious people, then take a minute to think if there is anything that can be done to prevent the problem from re-occurring. You usually cannot remove all chance of it happening again, but you may be able to take some steps that will greatly reduce the chance of it happening again. For example:

- If the problem was related to malware being installed from a website, then anti-malware software could be installed.

- If the problem was a dropped laptop, then a proper carrying case can be provided.

- If the problem was a file that was modified or deleted, then you can adjust the security or permissions on the file to prevent it from happening again.

By helping your clients this way, you may not see them back with the same problem; but this type of action will increase the level of trust between you and the client, which will bring the client back to you in the future.

Going the extra mile also involves contacting the client in the near future to ensure that your work properly resolved the issue and that he or she is happy with the service you provided.

Documenting findings, activities, and outcomes

The philosopher George Santayana said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” To remember a solution for the long term, write it down or otherwise record it. If you do not document your findings, you might find yourself repeating the same troubleshooting steps in the future to solve a similar problem, when the process could have been abbreviated.

I recommend using a personal or a corporate knowledge base to record troubleshooting activities. Some companies have a formal help desk or trouble ticket system, with the main goal of documenting their problems and solutions. Having a technician close his trouble tickets with “Problem resolved” might be fast for the technician, but it is not the purpose of the application. One of the application’s goals is to build a database of problems and resolutions. The more detail that is included in the resolution documentation, the more helpful it will be in the future.

After the trouble ticket database has enough information, it becomes more than a place where the information is stored: It also becomes a place where solutions are found. The larger the database, the more likely it will be able to provide your solution. When a problem is reported, you can search the database to see whether the problem has previously happened for that person (or another person), and you might be provided with a solution. Testing a few known solutions is faster than starting the troubleshooting process at the beginning.

Depending on your job role, you may also need to document the solution for your clients, so that they have a permanent record of the fix or a record of how you spent your time.

Professionalism and Communication

Whether you are an internal or external support professional, you have customers. For the external support professional, it is easy to identify your customers. For the internal support professional, the people for whom you provide support are still your customers, and you still need to provide them with service. To provide this service, you will be required to communicate with them, and this communication should remain professional in its tone and manner. The best way to maintain the right level of professionalism is to respect the customer; whether the customer is right or wrong, you should still give him respect. You can show him respect while you educate him, work with him, or explain to him what he doesn’t understand related to the technology that he is using.

The professionalism and communication section of the A+ Exams should be common sense for most readers. The exam questions will present a wide range of responses to given scenarios; the answer will usually be the one that illustrates good communication skills and respect for the client. Verbally abusing the client and hanging up will not be the correct answer!

The professionalism and communication section of the A+ Exams should be common sense for most readers. The exam questions will present a wide range of responses to given scenarios; the answer will usually be the one that illustrates good communication skills and respect for the client. Verbally abusing the client and hanging up will not be the correct answer!

Good communication skills

What we’ve got here is a failure to communicate.

— COOL HAND LUKE

A breakdown in communication can be blamed for many of the problems that exist in our world today. Difficult customers or situations are a source of conflict, but that conflict often begins with a misunderstanding. To avoid this conflict with your customers, always make sure you use good communication skills. Here is a list of things to keep in mind when communicating with a customer:

- Listen to the customer and don’t interrupt. One of the best abilities of a good communicator is the ability to listen. All too often in today’s society, the emphasis is on speed; and for the sake of speed, people tend not to listen. The active part of “active listening” is still listening. Part of “not listening” is completing other peoples’ thoughts or sentences. This is a problem that can be resolved by resisting the urge to just jump in and taking notes to discuss after the customer has finished her statement. Put yourself in the listener’s position while you let the person tell you the problem and how it is affecting her life. “Not listening” can extend to email. I have written emails to vendor support addresses, detailing a problem and the steps already taken to solve that problem, only to receive a stock reply from the vendor support person saying, “Try this,” which was already tried, or does not address the problem. At times like that, I usually reply to the email, stating the fact that he failed to read message and rather suggested a solution based on the subject line or the first line of the message.

- Clarify statements and repeat what you have heard. One technique that helps to clarify any misunderstandings is to repeat to the user what he told you. This reinforces for the user that you are listening and are not daydreaming. It also verifies that you understand what the user said. When you repeat it, you may substitute terms or give additional examples of what the client described to you. Ask questions to gather additional information about what the customer is saying.

- Use open verses closed questions to gather information. Open-ended questions will encourage the customer to provide additional information, rather than closed-ended. A question such as “Describe what you saw,” is better than “Did the screen flicker?” You may get information you did not expect when using open-ended questions.

- Use clear, concise, and direct statements. Translation: Don’t be long-winded. Many people like to hear themselves talk; resist any temptations to verbosity you might have. Don’t use a $10 word when a 25¢ word will do. Keep your statements direct with clearly focused points.

- Avoid tech talk. As a CompTIA A+ Certified Professional, you are constantly exposed to technical terms and abbreviations that you slowly incorporate into your vocabulary. However, not everybody in the general public is familiar with RAID, asynchronous, MTBF, SCSI, and a whole slew of other terms can confuse clients who refer to the computer as being composed of a monitor and a hard drive. Whenever possible, try to gauge the user’s knowledge level and use an appropriate level of terminology.

Professional behavior

Always try to conduct yourself with professionalism. Doing so generates respectability in the eyes of your clients and supervisors. The following list contains some aspects of professionalism that should be practiced:

-

Positive attitude: It is often said that animals can smell fear on a person. The same is true of users: They can smell a negative attitude right away. You should approach each client and each job with a positive attitude and a feeling of confidence. If you do, you will get more satisfaction from your job. Regardless of your position, there will likely be some aspects of your job that you don’t enjoy, but don’t let these things bring down your attitude.

In most cases, you deal with clients who have problems that might put the client in a foul mood. If you seem happy to see a client, he will likely lighten his mood, and you will both have a more positive experience. Win/win.

This could go in reverse if you let it: The client’s negative attitude could dampen your mood. Don’t let this happen. Stay positive.

This could go in reverse if you let it: The client’s negative attitude could dampen your mood. Don’t let this happen. Stay positive.

- Project confidence: As with a positive attitude, it is important to project confidence in your role as a CompTIA A+ Certified Professional. Having confidence in your actions is important to establish trust with your customers and to increase their confidence in you. This does not mean that you always need to know the answer; but it does mean that you need to be confident even when saying you do not know. You are always able to tell the customer you will find the answer for him.

-

Proper dress: Professionalism likely includes appropriate attire as well as attitude. When choosing what to wear, plan around the jobs you are doing. Client meetings might dictate formal business attire; if you are expecting to pull cable through crawlspaces, though, something more casual would fit the task.

Regardless of the job, your clothes should be clean and well-kept. To a client, a shoddy appearance indicates shoddy work.

Regardless of the job, your clothes should be clean and well-kept. To a client, a shoddy appearance indicates shoddy work.

-

Privacy, confidentiality, and discretion: It’s surprising what information clients are willing to let you see on their computers. In many cases, you have access to their most private documents. In corporate environments, this can include confidential employee information found on the computer you are servicing, documents left in a printer, or documents and material left on the desk at which you are working. When doing retail bench work, this can include private financial information that is in their computer. In both cases, a client’s computer often holds information that you should not be seeing — and, in normal circumstances, you would not be allowed to see. In most cases, you will know what you should and should not be looking at. If there is a reason to open a file to verify accessibility, then sure — you will need to do that. However, you should ignore the information you find when you’re done. Here are few additional key items to remember when dealing with this topic when working as outside IT professional:

- Some companies have high standards when sharing information with you, and may have issues with you accessing any data on the computer — especially if you will be unsupervised. Be cognizant of this, and ask permission before continuing if you think there may be a concern.

- If customers express concern in respect to your access to data, take steps to put them at ease.

- Be familiar with government regulations that may affect your data access requirements related to their customers’ personal data. Some industries, such as healthcare, have very stringent guidelines.

- Check your own company guidelines on data access and retention, which may be more strict than the customer’s own guidelines.

- Do not confuse the line between customer confidentiality and the law. There are no client–IT professional privileges, so if you stumble over something that is illegal, you are obligated to report it to the appropriate authorities.

As an outside consultant, I am amazed by the number of clients who freely offer up administrative credentials for their network, granting access to all areas of the network and to all kinds of information. Take care to ensure that these credentials are not misused by you or put in a place where they could be used by another person without your knowledge.

As an outside consultant, I am amazed by the number of clients who freely offer up administrative credentials for their network, granting access to all areas of the network and to all kinds of information. Take care to ensure that these credentials are not misused by you or put in a place where they could be used by another person without your knowledge.

- Social media: If you are going to respect your customer’s privacy as you just read, that means you should never post information about your customer or your experiences with your customer on any social media sites. That should go without saying, but with many people I know, it does need to be said, and then said again. Many companies have people who are given the job of monitoring the company’s references in social media, so what you are saying may get back to the company, even if you think you are a using a private or semi-private medium. In the worst cases, dismissal or a lawsuit may be the result. The best words of advice I have for you, were given to me early in my online life: “Never put anything into an email (or social media post, tweet, blog, vlog, or whatever) that you would not want to appear on the front page of a newspaper.”

- Expectations: Many issues may arise from a different level of expectation between you and the client. Make sure that you set or agree upon expectations, and work to meet them:

- If a variety of service, repair, or replacement options are available, discuss them with the client and ensure that the client knows which one you will be working on.

- If you need time to perform the work, set the expectation as how long it will take and, if something happens to change the time, make sure to follow up with the client.

- You may want to follow up with the client after the service to ensure that the repair work was satisfactory and that the problem did not return.

-

Respect: People with different cultural backgrounds will have different means of showing respect, and you should use techniques appropriate to your local region or culture. In general, the techniques listed here are fairly universal. Respect should be thought of as a two-way street. In most cases, if you show appropriate respect to your clients, they will return that level of respect.

If the client doesn’t show you any respect, stay calm and continue to be respectful. Ask the client to calm down and tell him that you will not be able to help if he does not give you the information you need. This is a tough situation to call because when people are told that they are not acting appropriately, they either calm down or become defensive and more disrespectful. While you tell them that they should calm down, make sure to reinforce that you want to help them. The logic of the situation might finally sink in.

Some steps or actions you can take to show respect are

-

Don’t argue or be defensive. The client might be in a foul mood. You would likely be as well if technology got in the way of your job or you thought that you had just lost several years of personal data or photos. A client might have many reasons to be upset when you start dealing with him.

To some clients, you represent the technology they’re having issues with. Their frustration often gets vented all over you. Don’t take this personally or get upset by users’ actions. Do what you can to relieve some of their stress and remind them that you’re not part of the problem. Rather, you’re part of the solution.

If you argue with the client, the entire issue will most likely become ugly. Avoid arguing at all costs.

If you argue with the client, the entire issue will most likely become ugly. Avoid arguing at all costs.

- Don’t belittle or minimize problems. In most cases, the problems that users face are serious to them. Even though you might not share their view of the importance of the problem, do not dismiss the issue. By claiming that the problems are trivial, you suggest that the clients’ feelings are trivial. If the clients were not upset before this point, they will be if they think you are trivializing them.

- Don’t be judgmental. Any biases you have should be checked at the door when you come to work. That way, you will likely reserve your judgments on issues until you have seen all the facts. This point goes very nicely with the previous one: namely, that if you pass early judgment on a user, you might be more inclined to trivialize her issues.

-

Avoid distractions and interruptions. When dealing with a client, try to reduce distractions for yourself. If you are working a help desk, you should not be carrying on conversations with those around you when you are on a support call. If you are working a retail repair bench, you should deal with one client at a time and not try to multitask among them or take phone calls. If you are visiting a client, you should silence your mobile phone and not take calls, text messages, tweets, or use other social media tools.

In all cases in which you are physically with a client, maintain eye contact. This will be taken as a sign that you’re paying attention. If you don’t maintain eye contact, the client will think that you are not paying attention. There is also a chance that you might become distracted by something you see. If you maintain eye contact, you will not get distracted by other events, and you will tend to have a better understanding of what is being said to you.

- Be on time. It is a good practice to plan your trips to a client site to arrive early. I once had a boss who told me, “If you are not 10 minutes early for your appointment, then you are late.” By planning to arrive 10 minutes early, even if something happens on your trip, you may still be able to be on time for that actual appointment. If something happens and you will be late, then contact the client with as much notice as possible. When I started in this industry, you did not have an option to easily contact the client while in transit; but in the current well connected world, the client can be contacted via multiple methods (email, text, or phone call) while enroute. When you know you are going to be late, let the client know.

- Property is as important as people. Respecting the person extends to respecting his or her property and privacy. For many clients, you will be working in their office, very possibly at their desk. When you’re waiting for a reboot or for software installation, you will be tempted to look around. Don’t do it! You should always respect your client’s privacy and possessions, from the computer to the Marvin the Martian action figure.

- Don’t bad-mouth other clients. Respect for a customer extends beyond the time you spend fixing his computer. Don’t be disrespectful of any client in front of current ones. If the client sees you lack respect for others or hears you say negative things about other clients, she will think that you are going to say similar things about her to your other clients.

-

Be culturally sensitive. With the globalization of IT services, as well as the multicultural makeup of so many countries, you will invariably be working with people from different backgrounds and ethnicities. Some care should be taken to avoid offending the people you will be dealing with, either as customers or fellow employees.

With the wide range of customs that you may encounter, this may not be possible all of the time; many of the colorful expressions that we have grown up with may be taboo. Whereas some of these remarks that we make can sometimes be thought to be colorful, it is easy to cross the line, in some cases without ever planning to. I once began describing a problem where only one control process should talk to the system, and used the expression “Too many chiefs … ,” and stopped there, realizing that I was working with a group of Native Americans; I have not used that expression since, opting instead for “Too many cooks … ,” and fewer hurt feelings.

Another way to display cultural sensitivity is to use proper titles when addressing customers. Many cultures have rules around the use of given and/or surnames. For example, in Chinese culture it is customary to always use the surname, but never alone.

In most cases, you prioritize the issues based on the impact to the user and the impact of other fixes implemented at a later time. One rule I live by is, “Fix the business problem first.” For example, if you are working for a stock trader, she needs her stock trading program working immediately, but she might be willing to wait for a fix to the word processing program.

In most cases, you prioritize the issues based on the impact to the user and the impact of other fixes implemented at a later time. One rule I live by is, “Fix the business problem first.” For example, if you are working for a stock trader, she needs her stock trading program working immediately, but she might be willing to wait for a fix to the word processing program. CompTIA lays out its recommended troubleshooting process as follows, but remember to take any corporate policies into account when going through the process:

CompTIA lays out its recommended troubleshooting process as follows, but remember to take any corporate policies into account when going through the process: The term layered is often used when discussing networking issues because the layers in the networking model are easily definable and are often referenced. For more information about the layered network model, see Book 8, which discusses networking.

The term layered is often used when discussing networking issues because the layers in the networking model are easily definable and are often referenced. For more information about the layered network model, see Book 8, which discusses networking. This could go in reverse if you let it: The client’s negative attitude could dampen your mood. Don’t let this happen. Stay positive.

This could go in reverse if you let it: The client’s negative attitude could dampen your mood. Don’t let this happen. Stay positive. (A) Apply one configuration change at a time

(A) Apply one configuration change at a time