2

Can the Black Superhero Be?

Blackness vs. the Superhero

I can change the order of things to suit my desperations.

—Essex Hemphill, “The Edge”

One of comics’ cognate representational forms—also defining late modernity, though preceding comics in their post–Action Comics form—is film. Much has been written about the entangled and mutually destructive (not of each other but of everything else) relationship between film and race. A few slivers chipped off that massive nightmarish iceberg provide a useful way to begin to understand how the pairing of blackness and the superhero—carefully twined together in chapter 1—presents a formidable challenge to the acts of being and doing that I’m ascribing to fantasy-acts.

On blackness in film, my go-to theorist for this initial consideration will be again, and again perhaps surprisingly, Fanon. Here in three among several instances in 1952’s Black Skin, White Masks, we find Fanon in a descriptive and reportorial rather than incisively analytic mood: “Whether he likes it or not, the black man has to wear the livery the white man has fabricated for him. Look at children’s comic books”—this, as you may recall, is the same moment we encountered in chapter 1. Fanon goes on, “In films the situation is even more acute. Most of the American films dubbed in French reproduce the grinning stereotype Y a bon Banania. In one of these recent films, Steel Sharks, there is a black guy on a submarine. . . . He is a true nigger, walking behind the quartermaster, trembling at the latter’s slightest fit of anger, and is killed in the end.”1

Later Fanon describes the acute predicament of watching movies while black: “I can’t go to the movies without encountering myself. I wait for myself. Just before the film starts, I wait for myself. Those in front of me look at me, spy on me, wait for me. A black bellhop is going to appear. My aching heart makes my head spin.”2

Elsewhere Fanon expands on this description after observing that “a host of information and a series of propositions slowly and stealthily work their way into an individual through books, newspapers, school texts, advertisements, movies, and radio and shape his community’s vision of the world.” Here he drops a footnote: “We recommend the following experiment for those who are not convinced. Attend the showing of a Tarzan film in the Antilles and in Europe,” Fanon suggests. “In the Antilles the young black man identifies himself de facto with Tarzan versus the Blacks. In a movie house in Europe things are not so clear-cut, for the white moviegoers automatically place him among the savages on the screen. This experiment is conclusive. The black man senses he cannot get away with being black.”3

These observations should bring us back to one of the problems posed when looking at Nubia in her leopard-skin skirt.

Contrast Fanon’s account of moviegoing with that of his contemporary Gore Vidal, another perhaps-unexpected guide here, but like Fanon someone whose writing style is married to a politics that I admire and from which I learn. Vidal here writes circa 1992 and thus forty years after Fanon, recalling his own more rhapsodic moviegoing but mostly describing films from the same period, the 1930s through 1940s. Vidal’s account is not explicitly or even implicitly about race in the movies, and yet, read in light of Fanon’s testimony, what he has to say is almost unintelligible to the neighborly interstellar visitor from Alpha Centauri without an understanding of race in relation to the movies:

As I now move, graciously, I hope, toward the door marked Exit, it occurs to me that the only thing I ever really liked to do was go to the movies. Naturally, Sex and Art took precedence over the cinema. Unfortunately, neither ever proved to be as dependable as the filtering of present light through that moving strip of celluloid which projects past images and voices onto a screen. Thus, in a seemingly simple process, screening history.

As a writer and political activist, I have accumulated a number of cloudy trophies in my melancholy luggage. Some real, some imagined. Some acquired from life, such as it is; some from movies, such as they are. Sometimes, in time, where we are as well as were, it is not easy to tell the two apart. . . . For instance, I often believe that I served at least one term as governor of Alaska; yet written histories do not confirm this belief. No matter. Those were happy days, and who cares if they were real or not?4

Vidal’s dreamlike association between watching movies and memories of an otherwise unrecorded gubernatorial sojourn in Alaska link up in the Harvard lectures that this quotation is drawn from, which braid together memories of movies, memories of personal life, and references to world and national history. Vidal’s first novel, Williwaw (1946), is set in Alaska, and the writing of the novel, Vidal muses, depended in a curious way on watching movies. Convalescing in an army hospital in Alaska after “having been frozen in the Bering Sea,” Vidal concludes,

I had, by then, started a novel, about a ship in a storm in the Bering Sea. After the hospital, I was transferred to the Gulf of Mexico. I was unable to finish this novel until I went to see Isle of the Dead [1945], with Boris Karloff. As Boris Karloff first haunted my imagination in The Mummy [1932], so Boris Karloff, as a Greek officer on an island in a time of plague, broke, as it were, the ice and I completed my first novel right then and there. . . . I have no idea what was in the movie that did the trick.5

The kind of haunting evoked by his encounter with moving images on celluloid is of course markedly different from the haunting of similar images for Fanon and his imaginary-cum-clinically-observed-patient Black Everyman. For Vidal, the fantasy evoked is of decidedly white American male imaginary possession of political territory—“my unscreenable Alaska,” Vidal calls it.6 Fanon and his black moviegoer, meanwhile, suffer vertiginous anxiety attacks and are all but hounded out of the cinema. Notice that identification with the hero or the villain, that somewhat misleading vector of engagement with comics discussed in chapter 1, is not required for Vidal’s fantasy of plenitude as it mingles with and becomes indistinguishable from memory. It is the very milieu of the film-as-story, the agreed-upon assumptions that facilitate the suspension of disbelief necessary to imaginatively enjoy via observing the film, everything about the movie and movies themselves, that guarantee the possibility, indeed the enticement, of an intermingling between past recorded image and present imaginations of the past.

This seamless transfer of information across the boundaries of real and imaginary, the active production of fantasy as world, world as fantasy, requires the payment of a particular ticket (to evoke James Baldwin): entry is difficult, and perhaps even barred, without white skin and, probably, without male embodiment. Both “white” and “male” here should be understood as socially designated, with very little give accorded to those persons who are not socially designated white/male but who might nevertheless think, dream, and imagine both themselves and the world in accordance with one or both those designations. Fanon’s Black Everyman was Tarzan in the Antillean theater, but cannot escape becoming savage or bellhop in the theater in Paris.

Yet I’ve been trying to think about and describe the ways that the very faculty beckoned into collusion by movies—imagination—is in comics not rigidly determined either by the one-to-one correspondences of identification or by the social position and embodiment of the comics reader. And we know, too, how nimble movie viewers’ imaginations can be in response to such proffers of the terms of entry and identification, and that one need never look at a movie star onscreen and experience a complete disjunction between him or her and one’s own self-conceptions. See, in this regard, almost anything written in the 1980s and 1990s in then-young cultural studies texts, but especially those of the black British cultural studies school. See Baldwin’s attachment to Joan Crawford in The Devil Finds Work (1976). See José Muñoz’s Disidentifications (1990).

I noted in the introduction how I could simultaneously both imagine having the privileges of whiteness and yet fail to fully invest in such an imaginative proposition. Another way of describing this contradiction—a way that parallels and neatly traces the contradictory elements—is the impasse I’m staging here between Vidal and Fanon at the movies. In both cases, the activity of fantasy is at once ignited and impeded. What I have begun to suggest in considering superhero-comics reading as a key paradigm of fantasy-acts is that superhero comics in both content and form also meet this impasse, and surpass it.

As a comics reader, my attention is not as limited as Fanon’s Black Everyman by the director’s construction of the camera’s frame in the movie theater. Yes, I reading a comic might “wait” cringingly for a too-familiar racist rendition of my own image to appear, I might see myself therein, I might perform seeing or viewing along the lines of a constant restless quest for identification and self-reflection compelled by my embattled sense of self among similar brethren in an antiblack world. Reading comics in the 1940s, as Fanon observed, there are images laboring to achieve precisely this end. See here the dreadful Whitewash Jones, pickaninny sidekick to the team of Captain America’s and the Human Torch’s sidekicks, Young Allies, in the summer of 1941 (figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1. Whitewash Jones hits the familiar minstrel comedy notes in the popular sidekick comic series The Young Allies 1, no. 1 (Summer 1941). (Joe Simon, editor; Jack Kirby, artist)

But in my reading of comics, I don’t have to perform seeing and viewing according to these racist mandates, because the multiplicity of images splayed across the page’s grid (or other arrangement of panels), even if they repeat themselves with slight differences, don’t compel the monological focus inherent to the camera’s frame. This multiplicity offers more, even, than the comparatively capacious proscenium span of the theater’s stage in a playhouse. The multiplicity of images invites, or at the very least the images permit, a dispersal of attention across a number of points, and in various combinations and sequences. Hence the quest for identification, if I have (foolishly) embarked on it, may be productively frustrated, rerouted to other quests or brought again and again to a failure to achieve identification.

What is offered by the comics page—something obscured in chapter 1 with our focus on the iconic singular image, however multilayered, of Nubia on the cover—is a kind of manipulability that lies not only in the hands of the author and artist (the analogue to the film director), but in the mind of the reader/viewer. According to W. J. T. Mitchell, the comics page is less like the movie screen and more like the computer screen in its availability to, and requirement of, “viewer” action. We may be (mis)led, Mitchell opines, to consider comics via the medium’s “inevitable rootedness in the extremely old media of drawing and writing; or its technical pedigree in the very modern invention of the printing press and the rise of newspapers and magazines; or its contemporary articulation as a kind of bookish and materialist alternative to the dominance of virtuality and screen-based media.”7 But we should rather see comics as “transmediatic,” “moving across all boundaries of performance, representation, reproduction, and inscription to find new audiences, new subjects, and new forms of expression. . . . Comics is transmediatic because it is translatable and transitional, mutating before our eyes into unexpected new forms.”8 In this way, we can see comics formally “as a media platform that, like the computer, can host every form of mediation. The main difference between these two platforms is that computers provide a mechanical-electronic platform via a screen interface whereas comics offer a manual-neurological platform via the page interface.”9

Whereas, then, as we see via Vidal, cinema—long understood as bringing into being a “male gaze”—also performs the inculcation of a white male gaze, which roves like Sauron’s Eye in search of differences to assimilate and territories to conquer, the comics transmedium offers a perspective that invites relationships to representation that do not assume and cannot compel conquering, assimilative responses that obliterate the threat posed by difference. “But what is the perspective of comics?” Mitchell asks. “Is it the point of view of comics artists? Or is it something impersonal, built into the very structure of comics as a medium? How can an impersonal system have a perspective? Is there a comic view of the world?”10 These are questions only answerable with/via the participation of readers. Comics’ “perspective” is not unlike the perspective of a computer—not just its screen, but what we do that registers on the screen. Thus “closure” provides the answers to Mitchell’s questions, but this means that the answers are as various as the kinds of closure, the kinds and qualities of participatory imagination, the kinds and qualities of fantasy-acts, that many readers provide to the comic singularly and in the uneven collectivities of fan communities, conventions, online message boards, printed letters pages, and so on.

I have circled back to comics-reading closure because it is central to the idea of fantasy-acts, and because it is with closure(s) that we put the sword to the Gordian knot tying together my imaginative adventure of having the privileges of whiteness and yet failing to fully invest in such an imaginative proposition. Put another way, this is where my inquiry crosses paths with a number of other currently urgent inquiries in African Americanist, Afro-diasporic, and Afro-pessimist thought, which we can see from such disparate and overlapping projects as Saidiya Hartman’s and Tavia Nyong’o’s discussions of critical fabulation and “Afro-fabulations,” and Christina Sharpe’s In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (2016): which is whether it is possible to have fantasies of freedom and power in the hold of the slave ship—if such ontological captivity is where we always remain, post-1492—and if so, what kinds of fantasies and to what, if any, avail.

Thus prepared, let’s now consider at greater length the questions I bracketed in chapter 1 that raised the strong possibility that a superhero cannot “be” a superhero and “be” signified as black at the same time. Let’s consider what “black” and “white” mean, and could mean, in the two-dimensional paper and digital world of superhero comics and in the multidimensional imaginations of their readers.

Black Superhero, Black Name

The white privilege in watching movies that gives rise to Gore Vidal’s fantasy of being a governor of Alaska is the same as, or linked to, the fantasy that forms the superhero in the character of Superman, in 1938. That the Superman character might be read as Jewish and therefore only aspirationally or provisionally white—he is the alien other who awaits the crown granted him by assimilation—supports rather than undercuts this proposition.11 Superman’s history recapitulates the history of whiteness for American immigrants, as ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny. Thus the paradigmatic comic-book superhero is in important ways conceptually white: if a superhero isn’t white, then the hero is an exception, a different case, since part of what defines the hero is his whiteness. Viewed conceptually, the superhero figure is historically “white” and cannot be understood except in relation to fantasies inspired and underwritten by social positions of whiteness.

It is worth noting, however, that since the comic-book superhero is a figure summoned into its fictional existence via the process of drawing and writing, its whiteness is also always the production via the ink, color, or digital process indicating the character’s “white” “skin” tones. This is a production that is both simple (because its practice has sedimented into a convention of the craft) and laborious (because the practice of coloring a character “white” requires work and finagling, just as giving Bruce Wayne and Superman black hair required playing with blues and blacks up through the Bronze Age). We can therefore perceive this production of the effect of whiteness as both conscious and unconscious in comic-book superhero creation and representation.12

Jeffrey A. Brown’s Black Superheroes, Milestone Comics, and Their Fans (2001) provides a field-initializing analysis of how the black superhero, in the fantasy universe where Whitewash Jones blazed the path, at first—if not always—threatens to burst apart as incoherent, as a potentially fantasy-busting derangement of the reader’s willingness to suspend disbelief. Brown’s focus is on the male superhero, because the superhero is also conceptually male, not unlike the way the “perspective” of Vidal’s (and Fanon’s) movies embedded the male gaze. Nubia’s departures from the norms of superhero representation—the departures that make her rich as a source for readerly imagination, both mine and many others’—are, again, transgressions of expected race and gender representation (a twinning of transgression that almost necessarily summons to mind other nonnormativities, including those of sexuality, thus giving rise to queer readings of various kinds, as I’ll discuss shortly). This is notwithstanding Wonder Woman’s iconic industry-standard status; Wonder Woman was always an outlier and, for many reasons, a queer figure.13

Jeffrey Brown argues that comic-book male superheroes’ extreme hypermasculinity (armor-plated musculature, varying degrees of invulnerability, etc.) presents various kinds of potential anxieties for superhero comics’ mostly male readership, not least the inevitable negative comparison between the hero’s drawn physique and the reader’s own. However, these anxieties are generally well managed within the conventions of the genre. Brown is working from the assumption, shared, as we saw, by Wertham and Fanon, that identification is the source and the end product of superhero-comics fandom or of reading superhero comics. Thus, Brown implies, the superhero characters’ represented effect of gender presentation—I parse this phrasing in order to again remind us that the characters are an achievement of drawing and writing, rather than beings of flesh—may impede the ease with which a putatively juvenile reader can “identify” with the male superhero, but nevertheless the channel for identification is sufficiently clear to be traversed and for the match to be made.

But Brown suggests that race—or rather, not adhering to or achieving the standard represented effect of whiteness—poses a less surmountable obstacle. The management of the anxieties about the possibilities of identification and idolization does not work well when the superhero is a black male, a figure already overdetermined in Western cultures as an exemplar of extreme, out-of-control physicality. “If comic book superheroes represent an acceptable, albeit obviously extreme, model of hypermasculinity,” Brown notes, “then the combination of the two—a black male superhero—runs the risk of being read as an overabundance, a potentially threatening cluster of masculine signifiers.”14

The evidence for the operation of this risk and threat lies not only in the relative paucity of numbers of black superheroes, male or female; that is a sin that can be laid at the door of the overwhelmingly white male creators of the superhero comics. The evidence lies chiefly in the fact that superhero comics featuring black male superheroes as their primary characters have historically underperformed commercially, even with the lower sales expectations that obtain for post–Golden Age comics. Black male superheroes in their own comics generally don’t sell very well relative to the majority of white superhero titles, and no title centrally featuring a black superhero has yet had the ongoing commercial presence of Superman, Batman, Captain America, Spider-Man, etc.

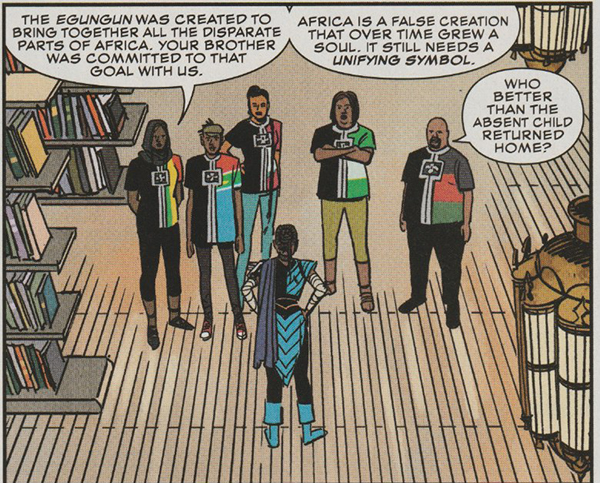

The phenomenal ticket-sales and pop-culture-zeitgeist success of the 2017 Black Panther movie—which coincided with the 2016 restart of the fifth iteration of Black Panther comics, written by MacArthur Genius Award winner Ta-Nahesi Coates—may ultimately make the Panther the exception to this rule. But Black Panther series (including its first iteration, Jungle Action) have begun with a flourish and then been canceled for lack of sufficient sales four times previous, which means that, so far, the Panther has been the strongest evidence for this rule rather than its outlier. It’s true that many, perhaps indeed the majority, of superhero titles are also canceled when the hero isn’t represented as black or a person of color. It’s also true that superhero titles featuring white women superheroes have traditionally suffered this fate, too, with Ms. Marvel / Captain Marvel having had almost as many cancellations and restarts as the Panther. Yet it is the case that none of the enduring single-hero titles that hail from the Golden Age of the 1930s and ’40s, like Superman, Batman, and Captain America, or that hail from the Silver Age of the 1950s and ’60s, like the Flash, Spider-Man, the Fantastic Four, Thor, and the Hulk, are represented as black or as a person of color.

The black superhero is always therefore an oddity, perpetually a lame duck anticipating his constitutionally mandated removal from protagonist status.

The names of black superhero characters once they arrived in the 1960s and ’70s exemplify the underlining and emphasis on the difference of blackness in the comic-book world. The fact that comic strips are a visual medium means that the creators’ drawings and color will prompt a reader to see that such a character is black—though as noted earlier with respect to the representation of whiteness in comics, this involves a not-uncomplicated series of illustrative choices for the artists and colorists. Note, for example, the peculiar cross-hatchings denoting shadow or melanin that Charles Schulz chose to place around the edges of the face of Franklin, the only black character among his round-headed cartoon philosophers in Peanuts.15

But the visual rendering of blackness was not enough of a representational gesture for the comic-book creators who crafted the early black superheroes. These creators often took the tack of also choosing a character name denoting blackness, as though offering instructions to the colorist who would enter the production process well after the drawing and writing were completed: Black Panther, Black Lightning, Black Goliath. We have already seen that the 1970s black version of Wonder Woman was called Nubia—and that even as that character has only fitfully reappeared since 1973, almost never with her Wonder Woman powers intact, she nevertheless retains and is identifiable by that name. This insistent tack is revealing in the way that someone’s saying, “He’s a male stripper,” is revealing—the redundancy shows that the speaker assumes that strippers are by definition women; as the early naming of black superheroes reveals that superheroes are by definition white.

The conventions of representation that provide the ground for superhero-comic-book literacy, then, retain as a lingering effect the unacknowledged white-supremacist assumptions at work in the establishment of the genre in the late 1930s and ’40s, when pioneer figures Superman and Captain Marvel burst onto the pop-culture scene. The black male superhero disturbs or fails to comply with assumptions established in the genre’s infancy; he is not entirely legible within those conventions. Due to the “overabundance” of signifiers coalescing around a black superhero figure, readers are not quite able to see, or are resistant to seeing, black superheroes and taking them on board as they do with Spider-Man and Superman.

Brown’s argument thus applies the well-established analysis whereby we understand the black male figure as exemplifying, indeed exaggerating as a thrilling spectacle, the contradictions and instabilities that inhere in the pairing of masculinity and power, of male bodies and the Phallus, in our patriarchal and misogynist cultures. The black male figure is generally described in cultural analysis as operating according to a kind of erection/castration paradox (to put the matter in vulgar Freudian terms). The figure is thus contradictory, at once hypermasculine and feminine. The powerful allure-and-threat of the black male figure’s insistent phallic preening is also an index of its bearer’s degraded social status, its position as object prone before an observing subject, which fears, desires, and aspires to control it. The two, degraded status and potential power, are inextricable from each other.

Here, then, in the realm of the consumption of black male superheroes, which is the consumption of images and narratives of fantasy, the black male figure, because he is at once ultramasculine and without masculine power, is both a spectacle (because he is different and cannot but shout his difference to all before whom he appears) and not fully visible (because he is different and the filters dictating what can be recognized do not recognize the peculiar data of his presence).

Black Superhero: Bad-Ass and Criminal

We can pose this problem that the black male figure as superhero presents at a slightly different angle, as well, which illuminates further the pressures besetting black male superheroes and throwing up hurdles to the successful elaboration of such a fantasy. Filmmaker Reginald Hudlin, the cocreator of commercially successful films centrally featuring African Americans, such as House Party (1990) and Boomerang (1992), took over a retooled Black Panther title in 2005. In an afterword Hudlin wrote for a collection of his first six issues, he describes the guiding principle of his vision of Black Panther and what he believed would probably ensure the title’s success. Hudlin says he was determined to align the Black Panther with what he saw to be most appealing about black male cultural icons in the “post-integration, post-Reagan” hip-hop era: black male cultural icons were bad-asses, Hudlin observes, and Black Panther needed to be bad-ass, too. Hudlin writes that what Spike Lee, P. Diddy, “Malcolm X, Miles Davis and Muhammad Ali, all have in common, is the knowledge that the act of being a black man in white America is an inherent act of rebellion. They are WILLING to be bad@$$es. . . . That’s what hip hop is all about. Being a bad@$$. Everyone wants to be a bad@$$. That’s why white kids have always loved black music. . . . Black music is the music of bad@$$es.” And “The harder the Panther is, the more appealing he is to both black AND white audiences.”16

It’s tempting to quibble with Hudlin’s reading of the history of black music pre-hip-hop and undercut his general cultural observation. We might counter by tracing a genealogy of his point of view back to like-minded comments made by the mid-1960s LeRoi Jones. Jones (before becoming Baraka) wrote when there was a prevailing tradition of images of black males that were rather more castrated than erect, and far from bad-ass—which Jones’s essays, poems, and plays often strove with all his rhetorical might to overcome. Nevertheless, Hudlin’s reasoning and choice of how to depict a venerable superhero character that he was tasked with making popular highlights for us the narrow gamut that the black male figure runs, and demonstrates another of the various traps which that narrow range lays for conceiving black superheroes. Hudlin assumes and tries to work productively with the spectacularity of the figure of the black body, the fact that its visibility is produced as an indication of difference that signifies hyperembodiment (with its implication of being inversely possessed of intellectual capacities) and/or “perverse” sexuality, elements that Hudlin could mine in creating the fantasy image of a bad-ass capable of dispatching any number of foes and villains—and, à la the Blaxploitation hero, attracting more than his fair share of adoring women.

But though a superhero beats up villains, a superhero in its basic conception isn’t necessarily a bad-ass, while a villain or an antihero very often can be one. The claim of the black male figure to bad-ass-ness owes a debt to histories of rebellion, as Hudlin notes, but it is also owed to the nigh-systematic production of the black male figure as exemplifying a difference so alien that it justifies, even seems to compel, surveillance, policing, imprisoning, and assassinating. The paradox at this angle simply reconfigures its basic terms: the black male is an “inherent” rebel in “white America,” which is thus to wield a kind of power, but the fact that he cannot but appear so on the stage of an America rendered white by his presence is the very achievement, indeed perhaps the foundational achievement, of white-supremacist conventions of representation and perception. The black male bad-ass is also thus a criminal.

It’s difficult to overstate, and difficult too to fully encompass, the extent to which the equation of blackness and criminality tangles the knot of signification presented by the black superhero—female as well as male. The black hero runs counter to that strain of superheroic ethos that’s all about the celebration and mythologizing of policing. The great majority of Superman’s and Batman’s early adventures involved hunting down bank robbers and murderers and other criminals, such that in many ways they were, and yet remain eighty-odd years on, costumed superpolice.

We begin to see, then, how the superhero is constitutively white insofar as whiteness is defined by, and is the offer of, innocence. To be or to have innocence is to be free of guilt, and to be free of guilt is to be constitutionally insulated from the consequences of harmful actions. To be innocent or guilt-free is never to have engaged in harmful actions (which is why it can be ascribed to the constitutionally irresponsible: children), or to have such harmful actions purged (“redeemed” or “forgiven,” notions obviously highly charged by Christian mythology in Western and Western-dominated cultures). The latter, the purging of accountability for consequence, is most efficiently accomplished via the allocation of overweening responsibility to a guilty party, whose presence and repeated condemnation thus secures the other party’s claim to innocence. The fusion of innocence versus guilt with whiteness versus blackness has of course been accomplished in history with all the vicious obsessive determination that our political, economic, educational, and cultural institutions could have brought to bear on that project—so evidently vital to the making of modernity—and continues to be feverishly, bloodily reiterated, primarily though not only via police violence, in the present.

To illuminate the machinations of innocence, guilt, and racial marking, I refer us to philosopher J. Reid Miller’s Stain Removal: Ethics and Race (2016). Miller challenges the enshrined conviction that ethics is a field of inquiry without necessary purchase on the racialized character of lived realities and thus ideally without antiblack bias. Miller exposes how a racially “neutral” ethical valuation can never be honestly proposed: imported into, and constitutive of, ethical categories themselves, is a foregoing valuation, a valuation that is newly inherited with each birth into the social world, as race. Miller carefully examines the biblical story of the curse of Ham, the son of Noah, mythological progenitor of post-Adam humankind, sifting through commentaries and teachings on the story that Miller argues establish it as a foundational text in the development of Western epistemes. The myth of Ham, as we know, has been deployed both to “explain” the otherwise apparently inexplicable presence of “black” people on the Earth and to justify their enslavement.

Of central import for Miller in the story of the curse of Ham is the fundamentally formative role played by inheritable guilt in giving meaning to the category of the human. Criminality founds the human. And the inheritable nature of criminality founds the notion of race. Miller shows that in the story of Ham, one is criminal not because of an act, but rather as a function of status over which one has no control, which is the nature of inheritance and legacy. Key here is that the law precedes the crime; the law makes the act a crime by designating the actor a criminal. Examining fundamental prohibitions that “Thou shalt not kill” and the incest taboo, Miller writes,

“Murder” and “incest” . . . are . . . conceivable as such only as what the law has already thematized as perceptive possibilities. If, therefore, the law does not merely judge these acts as crimes but simultaneously and actively “founds” them, this could occur only via the identification of phenomena as criminal within an existing economy of value. Moreover, even if a crime or its anterior prototypes could generate directly a law it still could not found the law: that which remains . . . a vast yet shallow procedural technology whose manipulability—that by which one could think and act “outside” or against the law—confirms it [the law] as an inessential apparatus rather than a worldly expression of value.17

Ham’s crime, for which he was punished by the curse of servitude and degraded status relative to his brothers, apparently involves the obscure offense of seeing his father naked, but otherwise is never satisfactorily detailed in the biblical texts or in their commentaries. What is important in the story is that Ham is given the position of bearing a guilt, however mysterious in origin or dimension, that is henceforward inherent to his being and that then is borne as an inherent “stain” by those on whom Ham’s role is imposed down through the ages. That it is the mythical Ham and his mythical lineage of descendants who bear the “stain” of criminality, without which there can be no ethics, is arbitrary; it could have been someone else, some other lineage, some other race. But it is this very arbitrariness that entrenches the power that orders human relations according to hierarchies and according to chosen “values,” that is, the fundament of ethics.

Thus,

The crime of Ham does not receive from the law a name upon its commission. . . . The transgression does not violate a rule, formula, or principle but rather strikes at the very source or possibility of rulemaking, threatening the assemblage of the law-producing machine. . . . Ham . . . represents . . . [a] means by which power is not so much redirected as it is enchanted in its effects. In a drunken display of indiscretion, the law, like Noah, lies exposed; but this revelation in which there is nothing to reveal is necessary for its acquisition of a “body.” The stain of value . . . generates discovery of the “body of law” in its naked or pure state of “natural law”—a nakedness covered and defended by its progeny who must invoke routinely that unstained purity as the law’s original and authoritative subjectively constituting force.18

Miller’s readings of the many versions of the Ham myth strongly suggest that the structural possibility of subjectivity is subjectivity’s antagonistic pairing with criminality. This criminality is apportioned to Ham’s lineage (the black) as the mode of confirming its opposite’s “blessings”—though even the blessed are never free from the precarity of being swept into criminality, because criminality is what determines and safeguards the privileges of blessing by serving as their limit. In Miller’s reading, all subjects of the West’s imperially created globe stand or take shape as subjects in relation to criminality, but Ham’s lineage is definitely “cursed” with the burden of taking shape as almost coterminous with criminality, rather than in distinction to it.

In this light, we can hazard that the superhero figure captures our collective imaginations in part by partaking of and playing out in bright colors and grand Kabuki gestures the drama of the Subject and his defining criminal, of Noah and his blessed sons defined by Ham and his cursed descendants. The superhero as figure performs as a fantasy-act the pleasures in fantasy and the offer via fantastic aspiration (insofar as identification is the pivot of the reader’s engagement with the superhero) of innocence—“unstained purity,” which, naturally, needs its guilty opposite in order to be innocent. The superhero is violent, yes, and he is engaged in fantastically consequential acts of beating others up, but those others, the villains, are the guilty—whose very names and modes of appearance and structural position in comic-book narratives indicate that their raison d’être is to harm the innocent.

The hero in turn becomes the innocent by receiving the villain’s harms or by violently punishing the villain—not only for his actions but, in a way that passes through the reader’s consciousness without comment or question because it is so unexceptional, for being the villain. The villain is a kind. The villain, when the map of his story is held up against the map of Western ethics as Miller sees it, is playing the role of the criminal race. This structure of story, repeated weekly in countless variations decade upon decade, can—or must—in this light be seen as a vigorous performance of the fantasy of whiteness: thus the superhero is constituting or effecting whiteness in the realm of fantasy: the superhero is doing (in a minor way) and being (in a major way) whiteness as a fantasy-act.

Black Superhero: Monster

The black male figure is of course often criminal or menacing, especially if he is presented as “strong” or “powerful.” His power is not infrequently in his criminality and his threat, which is what Hudlin implies.

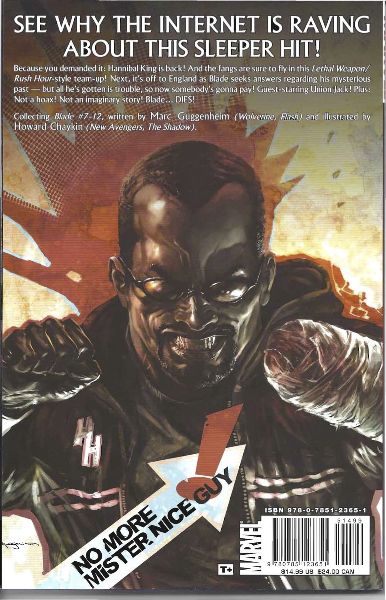

The Marvel horror-comic superhero character Blade provides an example of how all these matters get knotted up in the practice of conceptualizing and presenting a black superhero. The vampire-hunting part-vampire Blade was the lead character in a three-movie film franchise starring Wesley Snipes (Blade, 1998; Blade II, 2002; Blade: Trinity, 2004). Blade is an example therefore of the Hudlin bad-ass black male hero, and was a precursor in film to the zeitgeist cultural apotheosis of Black Panther. Blade’s spike of popularity in the late ’90s and early 2000s did not appear to translate into lasting strength of presence in the imaginations of superhero-comic-book readers, however. As of yet, the character has enjoyed no title of his own that was not either a miniseries or canceled for lack of sufficient sales, though Blade frequently guest-stars in other popular series such as Deadpool, and as of this writing, he has been a recurring cast member in The Avengers and a lead in the new team series Strikeforce.

Blade was originally a supporting character—and nemesis—of Dracula in the 1970s Marvel horror-comics series Tomb of Dracula, written by Marv Wolfman and drawn by the great Gene Colan (figures 2.2 and 2.3). In this first incarnation, the character was a more or less normal human being rather than a superhero—appropriately enough, since Tomb of Dracula was not a superhero series, even if superheroes occasionally guest-starred in it. Blade’s visual signature—the elements by which he was distinguished from other figures on the pages of the comics, not a few of whom carried wooden stakes just like he did—was brown-colored skin tones and a short afro, and a set of clothing choices that appeared to do the work of racial marking in that they were faintly redolent of Blaxploitation film icons Shaft and Superfly: these included a short, sometimes-green, sometimes-brown peacoat (supposedly leather, though it never looked it) and green goggles (evidently to help him see at night when hunting vampires).

Blade’s raison d’être was a vengeance mission: a vampire had killed his mother, and he was determined to eradicate the species from the Earth. In pursuit of his revenge, Blade struggled with a doppelganger who was, in fact, a vampire that had been mysteriously created via mysterious nineteenth-century German superchemistry at the behest of Deacon Frost, the same vampire who murdered Blade’s mother. For a few issues of Tomb of Dracula, this doppelganger killed the original Blade and managed to somehow absorb Blade’s memories and knowledge. But this challenge to Blade’s identity and mortality was soon rectified by the timely magical assistance of the Son of Satan—a half demon with father issues and hence a superhero in his own right. When Tomb of Dracula came to its end after about seventy issues, Blade and his green goggles and vampire-hunting heroics sank into comics limbo with it.

Figure 2.2. Blade’s first appearance in Tomb of Dracula #10 (1973). (Gene Colan, artist)

Figure 2.3. Gene Colan’s Blade, in Tomb of Dracula #45 (June 1976). (Marv Wolfman, writer)

In the movie franchise and in the comic-book appearances inspired by the films’ success from the late 1990s onward, Blade became what the comic character had fought not to be, a vampire-human hybrid—thus, in two senses of the word, revamped. This new, more existentially troubled Blade became retroactively the result of Deacon Frost biting Blade’s mother while Blade was in utero. The filmmakers and Snipes chose a number of visual and behavioral alterations in order to impress upon viewers Blade’s more highly charged and now superheroic status—as well as his otherness, his difference, which was, as it turned out, the primary source of his power and superheroism, more so than vengeance and the pursuit of justice. Blade’s look was transformed: the brown/green leather peacoat and goggles became sexy tight leather pants and a flowing cape-like black leather duster coat; the original Blade’s ’70s afro became what appeared at the time as a 1980s-style fade (the fade not yet having had the renaissance it currently enjoys), with a widow’s peak ever more severe with each subsequent movie. Blade’s persona, previously voluble and unconvincingly hip during the talky thrashings he would administer to the evil undead, became Hudlinesque bad-ass, his face always stony or clenched in inexpressive-to-angry expression and his speech laconic and replete with growls and grunts. Plus the revamped Blade sported the big muscles of a bona fide superhero (the old one’s leather jacket was too loose to discern much by way of physiognomy), he bristled with exotic weaponry, and he had big fangs.

Figure 2.4, from the cover of one of the short-lived series inspired by the movies, is an apt rendering of Snipes et al.’s redo of the character. There and in figures 2.5, 2.6, and 2.7 from the comic, we can observe the way that Blade’s superhero image steps into that narrow range of bad-ass appeal allowed to the black male figure. The authors of Blade’s look clearly mine the black male figure’s tendency to signify threatening difference itself—and thus frequently to appear in various discourses as alien, nonhuman, or animal—into a constitutive aspect of Blade’s superhero power. The contrast with the appearance of the Superman paradigm is evident. Blade’s post-film-franchise revamped look emphasizes his being other than human, while Superman, who is also not human, passes for human, albeit human of a white paragon sort.

Figure 2.4. Blade cover image from a 1998 short-lived series. (Blade #2, November 1998; Bart Sears, artist)

Figure 2.5. Cover image from another short-lived Blade series. (Blade #1, vol. 1, December 1999; Bart Sears, artist)

Figure 2.6. Splash page image from Blade #5 (vol. 2), September 2002 (Steve Pugh, artist; Christopher Hinz, writer)

Figure 2.7. Back cover image for Blade: Sins of the Father (2007). (Marko Djurdjevic, artist)

The emphasis on Blade’s vampire nature in his look can be said to tap into the menagerie of grotesque images commonly used to elicit audience discomfort in the horror genre. In this respect, Blade takes up an aspect that the other paradigmatic superhero, Batman, was originally meant to exemplify (though in Batman’s case, with only occasional success throughout the character’s long history)—that of being frightening, presumably to his enemies but also, in the thrilling way of horror, to his readers. But this representational tactic is given a particular twist in Blade, in that it is the black male body—always already borderline monstrous—that is the bad-ass hero, a hero who is visually as or even more terrifying and more potentially productive of nightmares and horror than the vampires he hunts.

In the movies, especially the first entry, most of the villains, including Deacon Frost, played by the slim, seraglio-eyed Stephen Dorff, are dressed chicly in nightclub attire and bright colors and look more or less like the attractive young white people usually cast as victims in a slasher flick. (Deacon Frost in the comics was a white-bearded old man, depicted wearing a kind of shapeless robe that completed his vaguely biblical look.) Snipes, whose good looks and smoldering onscreen sexiness made him more than adequate to play romantic and heroic leads on several occasions, is in the film’s reconceptualization of the comic-book character a different genre of black male body, one that is the site of discomfort with an erotic frisson, and perhaps of horror (with its usual erotic frisson).

The comic-book images repeat and actually push this representational tactic farther, as though making up for the lack of audible growls in Snipes’s onscreen performance with elaborate visual disfigurements. Thus the post-’70s popular Blade is both the monster of whom the audience is horrified and the hero who slays the monster. His figuration at once capitulates to and exploits the familiar erection/castration paradox.

Blade is an extreme, but he is not alone in the universe of comic-book black superhero depictions in being other and inhuman in his appearance and in tending to be depicted as less than Superman-handsome. Note figures 2.8 and 2.9—cover renderings of the first black superhero, Black Panther, at his most cat-like, and you’ll recognize that the hero with whom he’s most closely visually identified, Batman, boasts greater contrast in costume colors and a partially visible, and therefore humanizing, face.

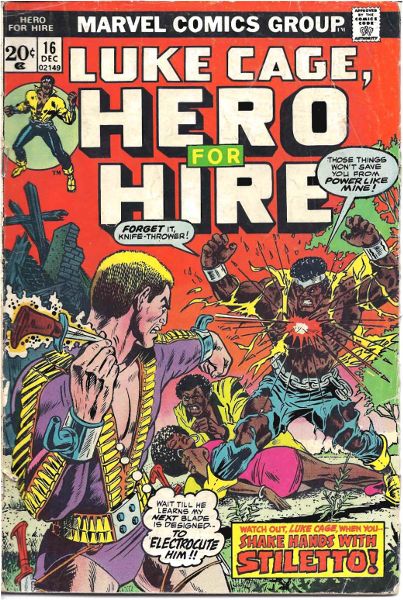

Along parallel lines, but with more subtle references to monstrosity, we see in figure 2.10 a 1973 cover of Luke Cage, Hero for Hire. Cage is the often-parodied but also beloved paradigmatic 1970s black hero, crafted by creators who doubtless spent instructive time watching Blaxploitation films. Not unlike Blade in his original version, his attire was a costumey noncostume, minus the typical cape, domino mask, or cowl. Cage wore a canary-yellow shirt, blue pants, yellow boots, an iron chain as a belt, and an iron headband to accent his short afro. (A well-crafted and generally well-received Netflix dramatic series—reported to be the fourth-most-watched show on the streaming service in its 2016 first season—adapted the character into live-action film capture. Among many other knowing nods to the various credibility-busting aspects of the 1970s comic-book series, the series lampooned the comic’s yellow-and-blue attire when Cage, played by the beautiful Mike Colter, was forced to don an absurd yellow shirt in one episode.) In figure 2.10, Luke Cage looks more like the monstrous Hulk than the heroic Superman, complete with clenched, menacing facial expression, quite unlike Superman’s typical splash-page serenity.

Underlining the general stress marking Cage’s appearance is the fact that his signature yellow shirt is being bullet-flayed from his body, so that the achieved color effect of his “black” skin is exposed. Indeed the ripping of Cage’s clothes (mostly his shirt, but sometimes his pants were shredded as well) and the exposure of the muscular dark-skinned body beneath was arguably itself Cage’s “costume” for the bulk of his early appearances. Certainly it was a signature visual trope of Luke Cage the superhero—like Batman backgrounded by shadows or perching on a rooftop. Of the first twenty-five issues of Luke Cage, Hero for Hire (renamed after issue 16 as Luke Cage, Power Man), which appear between the issue dates of June 1972 and June 1975, I count thirteen covers depicting Cage’s shirt and other clothing being ripped from his body. Within the pages of the first twenty-five issues, only twelve do not show Cage’s shirt being ripped away (though the thirteen where Cage’s clothes are being ripped off inside the comic are not necessarily always the same comics as those where Cage’s shirt is ripped on the cover).

Figure 2.8. The Black Panther by Jorge Lucas on the cover of Black Panther #46 (vol. 3), September 2002.

Figure 2.9. The Black Panther on the cover of Black Panther #58 (vol. 3), June 2003. (Liam Sharp, artist).

Figure 2.10. Luke Cage, Hero for Hire loses his shirt once again. (Hero for Hire #16, December 1973; Billy Graham, artist)

The ostensible logic justifying the repetition of Cage’s clothes being ripped was that his superpower is his diamond-hard skin. To acquire this power, Cage agreed to be subjected to a scientist’s dangerous experimental treatment, because he hoped doing so would earn him parole from prison, where Cage languished on trumped-up charges. (In order to receive his power-granting treatment, Cage had to be naked—of course—and this was depicted with shadows artfully covering the figure’s crotch. This scene was pivotal in issue 1 and repeated whenever Cage’s origin was recounted; I have not counted issue 1 or any of its replays as one of the issues in which Cage’s clothes are flayed.)

This superpower, essentially a take on Superman’s fabled invulnerability, allowed Cage to be seen with bullets bouncing off his chest just as they always bounced off Superman’s. Unlike Superman, however, Cage’s clothes lacked the resistance to bullets that is evidently a property of Kryptonian flying togs. In a bid for the “realism” that Superman’s adventures fighting-in-costume lacked, when Cage was shot or knifed or ray-blasted, as he always was, Cage’s clothes could not and did not survive. This was, however, a dictate of realism that had been bypassed in the depiction of the iconic Marvel Comics heroes the Fantastic Four, whose clothing morphed with the changes of their bodies (stretching, invisibility, bursting into flame) and kept their modesty intact. This representational convention maintained the Fantastic Four’s depictions within the strictures of the Comics Code Authority, presumably, but was explained in the comics stories to be the result of the scientific genius of clothing made with “unstable molecules.” (In a typical Marvel Comics crossover, Cage meets the Fantastic Four and their resident scientific genius, Mr. Fantastic, in issue 9 when Cage battles the Fantastic Four’s archnemesis, Dr. Doom. He borrows a rocket to fly to track down Doom, but neither asks for nor is offered a canary-yellow shirt made with unstable molecules.)

The availability of the figure of the black body to “pornotroping,” as Hortense Spillers elegantly terms it, is obvious here.19 But let’s place aside—for the moment—the meanings and possibilities for imaginative flight that coalesce around superhero-comic storytelling that repeatedly relies on unclothing a black male superheroic body in comics read by a great many if not a majority of consumers who were white, male, and young.

It is noteworthy that the defining visual insignia of this superhero character is to recur to the slashing of his shirt. As though this repeated shirt-slashing and body-baring were a stand-in for the violence directed against black male bodies in practices of lynching and routinized punishments of slavery, imprinted in the American cultural consciousness. As though the violence of ripping his clothing apart were a kind of counterweight necessary to render more appealing or more believable the concept of a black man possessed of superheroic power, the other side of a coin needed to make the currency of the image recognizable for the exchange of fantasy inherent to the commercial life of the comics industry. As though the writers and artists gauge that we readers need, or perhaps simply crave, an underlining, a reassuring or bracing reminder, of the black superhero’s blackness: that is, if we can’t get what it’s deemed we need in the character’s name—“Luke Cage,” “Hero for Hire,” and “Power Man” lacking the signal “Black” that is so conveniently appended to the Panther, the Lightning, the Goliath, and lacking the inherent blackness of “Nubia” or the telltale minstrel flavor of “Whitewash Jones”—then the character’s costume must be ripped away to reveal the color of the fantasized “skin” underneath: this, in a universe of disbelief-suspensions and shared imaginative conceits where a superhero’s costume is the very thing that shows us they are a superhero if they happen not to be doing something clearly superheroic in a given panel (like flying, or punching through a wall).

At every turn, what we see is that an adjustment in expectation, a reframing and rethinking gesture, must be made in the text or the image or both where the black superhero has the temerity to appear. The superhero is white; when or if they aren’t, new visual vocabularies or nomenclatorial legerdemain must be put into play. Or so the creators of the superheroes have apparently gambled.

Black Superhero: Power to the People?

The adjustment needed in the minds of the creators of the white (male) paradigm superhero, of their later followers, and of their imagined readers and buyers—at least as evinced by their creations—is not only visual and textual. A conceptual adjustment is also needed. Luke Cage’s problem (and Black Panther’s and Blade’s) might well be that as a black figure he’s confined by the history that produces blackness, a history that a range of shorthand cultural references renders into a history of defeat and loss and suffering.20 In this vein, we might surmise that part of what prepared the warm reception for Superman in the imaginations of millions of readers is that he arose alongside the World War II triumph of US military and economic dominance and the post–World War II United States’ arrogant international exportation of US cultural products: thus the triumphs of superheroes in the fight against evil on the comic-book page were, and still are, secured in the readers’ imaginations by the perceived political, economic, and military triumph of the nationality (and people or race) of which the hero is a super representative. Given such a context, it’s difficult, then, to pose even an edgy antihero character like Blade, even in the postintegration, post-Reagan hip-hop era, in which Hudlin detects a tendency to worship the black male bad-ass. This is because by simple dint of the character’s blackness, he is tethered to a history in which triumph has by and large not been secured in reality or in the readers’ imaginations. (Again, he is a bad-ass insofar as he is an inherent dissenter from an order from which he is a dissenter because he does not control it.) Blade is a super representative of a historically subordinated or defeated group or, at least, a group that is so perceived: How can comic-book creators, fantasy purveyors, and we who consume their creations as templates for our own fantasies imagine a powerful black hero who is triumphant, given such a history? And if he is truly powerful, why does he not use his power to transform the history he lives through to effect justice for his people?

Three ways to solve the problem:

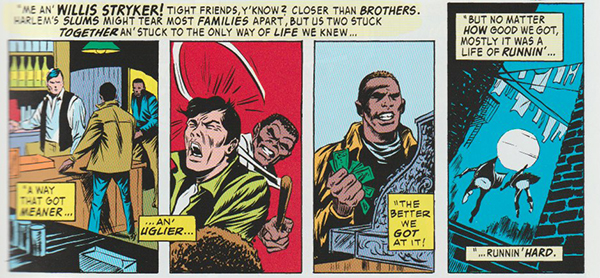

One way is for such a hero not to be noble in his intentions, that is, for him to be shady, quasi-criminal—as Luke Cage originally was. The way the character’s creators, Archie Goodwin (the writer of Hero for Hire) and George Tuska (the artist), both white men, conceived Cage’s origin story, Cage was put in prison for a crime he didn’t actually commit. (The inker for most of the first twelve issues was Billy Graham, who was black; Graham was the sole credited artist for issues 13, 14, and 15.) The story that Goodwin and Tuska invented was that Cage’s compadre Willis Stryker planted narcotics in Cage’s home to punish Cage for stealing the affections of a woman they both desired, Reva. But prior to this Stryker and Cage had become bosom buddies—“closer than brothers,” Cage testifies in issue 1 (see figure 2.11)—by surviving the “streets” and “slums” of Harlem together. Their mutual survival involved engaging in petty crime: the panel art shows Cage and Stryker counting the money of a purse they’ve stolen, knocking out a white man with a stick, and grabbing a fistful of bills from a cash register. It is during the time that Cage forges his brotherhood with Stryker that Cage becomes a proficient and feared fistfighter, earning “street gang leader” status due to his pugilist skills.

The differences are striking between these images and those of baby Superman lifting a tractor on a farm, or of the mild-mannered Clark Kent in his glasses choirboy-ing it up in the offices of the Daily Planet, or of the images of wealthy Bruce Wayne and his parents accosted by a similar kind of criminal (a mugger) that Cage is depicted to be. The story of Luke Cage’s origin, the story, that is, that introduces him to readers and that justifies his powers and his position as a superhero, is a story of criminality, however petty. The story of how Luke Cage becomes a hero is a story that partakes of and cements one of the most widely believed dictums of white-supremacist meaning-making—blacks commit more crime; blacks are criminals. In precisely this way, Cage is a super representative of his race. What makes him a black superhero, then, is his criminality. Luke Cage’s criminality is the past of his origin, the kernel and seed of his elaboration and unfolding: it is through this gate—a bloodstained one, à la Frederick Douglass?—that Luke Cage enters into the sphere of imaginary superhero fantasy. Cage’s origin is in criminal associations.

It’s true that the trajectory of Cage’s development is that he breaks free from criminal activity in his journey toward heroism, after a purgatorial sojourn in prison. But it must be said that even the break from criminality is sidetracked by the character’s creators’ “realist” innovation of having Cage hang out a shingle as a “hero for hire,” rather than offer his services gratis to a needful public. This innovation was actually a retread, the same tack having been tried and quickly discarded within the space of a single issue by spider-bitten Peter Parker, who gives up trying to make money with his powers once he learns via tragic loss that with great power comes great responsibility. Cage, however, holds onto the idea of mercenary heroism much longer, as though, in order to answer the questions raised by the very concept of a black superhero, he has to remain connected to his “hustler” past for a time, fully as much as he has to be stripped of his clothing for a time. (After issue 25, Cage’s episodes of having his clothes flayed from his body decrease.) Thus the condition for Cage’s becoming a hero—where “condition” refers both to a state or mode of being, and to a prerequisite or stipulation without which the performance of a thing cannot proceed—is his criminality. Following J. Reid Miller’s observations of the concept of the guilty category as preceding and founding the law that apportions guilt to acts and persons in that category, we would expect nothing different.

Figure 2.11. Luke’s criminal past remembered in Luke Cage, Hero for Hire #1 (June 1972): 9. (Archie Goodwin, writer; George Tuska, artist)

Black Superhero: Victim of History

A second possibility for conceptually appending “black” to “superhero” is that the black superhero can be a victim en route to the acquisition of his powers, so that his history recapitulates that of the people whom he represents. In this way, the operation of that history remains undisturbed, offering no challenge to our imaginations of what blackness signifies and thus neatly cordoning off avenues of imagination along which we might travel toward blackness with hitherto-undreamt meanings—or, for that matter, toward conceptualizing the superhero in ways we haven’t before. Blade exemplifies this tack. Like Superman, he is an orphan, whose lost parentage is the source of his superheroic difference: Superman is the son of aliens from Krypton, Blade the offspring of a vampire. Both are made heroes by leveraging what is imagined to be a biological difference in order to fight against evil. Essentially like Superman but to a much lesser extent, Blade is super strong and fast and is always able to heal from injuries (i.e., he is invulnerable). Yet this triumphant and powerful and even, in fantasy or ideological terms, paradigmatically (white) American position—escaped or exiled from the Old World, willfully remade stronger and better in the New—is for Blade the result of a curse: a vampire bit his mother and/or murdered his father, depending on the version of his origin. The curse is of course an apt, if never fully adequate, abbreviation of the position of blackness and black people in that quintessential American mythology of rebirth: this part of our common ancestry, the large portion that “arrived” in order to be made black, did not escape and was not precisely exiled—rather, they were condemned to be made anew. If the black hero is a victim (as Cage is, too, in addition to being a criminal), then the white-supremacist order requires no imaginative restructuring.

Here in comics as elsewhere, the historical and culturally sedimented truth of white-supremacist domination over black people becomes a stumbling block to the imagination of black characters possessed of power and to the imagination of blackness articulated to power. What this speaks to is that in addition to what Brown observes as the surfeit of signification that attends the black male image in superhero comics, there is also the conceptual problem of imagining a black hero in comics when white supremacy is or has been the actual order.

Contrasting this second tack with the first, it appears that it is not only the ontological attributes of blackness—that is, to be black is to be criminal—that must be kneaded to fit the shape of a superhero concept that otherwise resists or cannot accommodate such attributes. The stories that white creators of black superhero characters have told provide the trace of yet another level of conceptual wrestling: what is confronted in this second tack is the presence of a history, a social history, which the putative blackness of the superhero summons inexorably to the comic-book page.

In this light—revising my observation earlier—an ontological attribute of blackness is history. As Fanon describes in that fateful moment on the train when his Black Everyman persona is assailed by the cry, “Look, a Negro!”: “I couldn’t take it any longer, for I already knew there were legends, stories, history, and especially . . . historicity,” Fanon declares.21 Historicity attends the interpellation of the black man. In our context, this observation suggests that a story told and/or imaged in superhero comics where blackness or black(ened) bodies appear(s) must be a story importing into it a certain referentiality, a pointing toward meaning and story beyond the simple appearance of the black character (inevitably a supporting character, of secondary importance): the black image and body is different from the norm (it is queer) and thus compels explanation or storytelling devices that situate its nonnormative presence—hence, it conjures the presence of history. Or we might, following Fanon, say that the appearance of blackness carries the weight, otherwise unacknowledged, a subsurface undertow, of the histories that produce whiteness and blackness but that the effectuation of whiteness necessitates remain concealed and ignored: whiteness is masked as “normal” and hence requires no explanation; but whiteness does require blackness, somewhere and somehow, or else it will not be white, and part of blackness’s function in securing whiteness is to carry the burden of signifying the historicity without which neither racial category has any meaning at all.

References to or evocations of history have no necessary purchase when the hero is colored “white.” Indeed, a foundational premise of the (white) superhero is that the fantasy in which we as readers participate leaps beyond the limits of any particular historical condition. A man can only leap tall buildings in a single bound in an imagination unfettered by—or (to return us to Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster and the origins of Superman) an imagination actively seeking relief from the fetters of—all the histories told and untold when humans have not flown. If the (white) superhero belongs anywhere in time, then it is to a posthuman future—or to another planet, where the extraterrestrial is the figure for the speculation of histories alternate to our own.

Regarding the latter, it would seem that the representational tactic of mining the ore of alternate history is richly promising, if we’re trying to break through impasses of imagination when creating a black superhero or taking a black superhero up as the template for our own fantasy-acts. Surely one way to hurdle these problems is not to concede to the history that produces blackness as the victimized handmaiden of white supremacy but—since this is fantasy—to refuse the link between blackness and its particular history. Imagine a history that played out counter to our own. There is, after all, filmmaker Quentin Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds (2009) solution: You’re creating fantasies, so why not make the story you tell have a history that diverges from the one we know? In Tarantino’s film, Hitler, Goebbels, Goering, and the whole of the Nazi command were machine-gunned and burned to death in the makeshift crematorium of a theater fire in Paris in 1944 at the hands of an avenging Jewish woman and her black male friend (and perhaps lover) and employee.22

In the introduction to Black Skin, White Masks, Fanon writes, with a flourish, “Man’s misfortune, Nietzsche said, was that he was once a child. . . . As painful as it is for us to have to say this: there is but one destiny for the black man. And it is white.”23 In that statement and in much of the argument of his first book, Fanon not only replaces a supposedly raceless but actually white/European normative account of child development within a patriarchal family with the history of racial formation. I understand him also to be describing the way that we are always, as I’ve written before, abject to the histories that precede and make us, imprisoned within a network and a frame and perhaps above all a language of “rules” and “the way it is” and “reality” that are not our creations or choices, but the sediment of preceding events and their calcification in practices and discourses that support and decree the continual repetition of those practices.

What is lovely to me about fantasy-acts is that it is possible to propose, to conceive, and to begin to flesh out a different rule and a different “way it is,” which can be because the fantasy society occurs someplace and somewhen else, and its history is different. Instructive as to the project of this kind of motivated fantasy-act is another ringing statement of Fanon’s “By Way of Conclusion” in Black Skin: “The problem considered here is located in temporality. Disalienation will be for those Whites and Blacks who have refused to let themselves be locked in the substantialized ‘tower of the past.’ For many other black men disalienation will come from refusing to consider their reality as definitive.”24

Comics in its form, and not only in its superhero genre variety, provides a powerful tool for refusing to consider an unjust reality as definitive, precisely because it presents its information, stories, and effects in and on readers’ minds by rendering temporality, and the problems entangled in the chains of linear temporality, as malleable. Hillary Chute, borrowing from cartoonists and comics-theorizing luminaries Art Spiegelman and Scott McCloud, observes, “Comics . . . most fundamentally, ‘choreograph and shape time.’ . . . In the vocabulary of the comics, the other key element aside from the gutter is the panel, also known as the frame. Comics shapes time by arranging it in space on the page in panels, which are, essentially, boxes of time.” Chute continues, “The conventions of comics would seem to dictate that each panel is a moment, . . . [but] time in comics . . . is weirder than that. The weirdness of time in comics is part of the medium’s force as a storytelling form. . . . Comics has the ability to powerfully layer moments of time.”25

Chute’s observation here is primarily about the challenge in comics’ representational form and representational tactics to temporality as we live it (i.e., the past is gone and irretrievable except via inexact and incomplete methods of reconstruction; only the present exists, etc.). Chute also guides us to an understanding of how we can—and do—read comics in ways that play with and refuse ordinary linear temporality.

When we try to find umbrella terms for the study of comics, we tend to privilege the sequential relation of comics’ image-and-text boxes, as in Deborah Whaley’s book title Black Women in Sequence (2015). But Chute, Spiegelman, and McCloud all suggest that sequentiality as it’s generally understood may not actually account for or define comics. Here W. J. T. Mitchell describes a commonplace of comics reading: taking in the whole page at once, skipping ahead to the end, returning to savor and reread the earlier pages (the past of the story). Analyzing a thank-you note given to him in the form of a comics page by cartoonist Nathaniel McClennen, Mitchell notes, “So far my analysis of Nate’s comic has emphasized its multiple temporalities and alternative pathways through sequences of images and words. But there is another way of looking at this work that is specific, if not unique, to comics, and that is the possibility of seeing the whole thing as a unified, synchronic structure, . . . a unified, yet internally differentiated body, playing upon temporal sequence and spatial synchronicity.”26

Following Chute’s method of looking to the testimony of comics creators themselves, I find a passage in New Zealander Dylan Horrocks’s comic book Hicksville (2010) especially helpful for describing what’s useful about comics in working with what Fanon identifies as “the problem . . . located in temporality.” Hicksville layers multiple stories: in the main narrative, the reporter Leonard Batts travels to remote Hicksville to make biographical inquiries about the hometown origins of a famous comic-book creator named Dick Burger; this is laid alongside several ministories in which favorite classic comic strips like Peanuts, Tin-tin, and superhero comics are lovingly parodied, and in which Batts seems to interact with Burger’s creations in “real” life.

In one of the ministories, a character called “the New Zealander” mimics Batts’s investigative journey as he travels to “Cornucopia”—a land bounteous in imagination, it appears—to interview “their greatest cartoonist, Emil Kópen.” The New Zealander asks the sage comics creator Kópen, “How is a comic strip like a map?”27 Kópen, naturally, speaks Cornucopt, helpfully translated for us into English with the help of a third character, a woman who translates between the New Zealander and Kópen. In Cornucopt, the New Zealander learns, the word for comics translates as “text-picture.”

The conceit buttressing this exchange is that the world-famous cartoonist Kópen has previously referred to himself, somewhat mysteriously, as a cartographer. Nevertheless, the New Zealander’s question strikes an odd note, appearing to assume connections that no casual reader of comics would be likely to make. Indeed, it is the kind of question asked by a more-than-casual reader, one who brings to the question a set of conclusions about the centrality of sequence to comics form and a clarity he thinks is commonplace about the metaphoric relation of comics’ formal sequentiality to the kinds of directions provided by a map—enfolding within the choice of metaphor a conviction that the relationship between a map and places in the world is one of transparent accuracy.

I read this conversation as a dramatic staging of a philosophical and formal question—or about philosophy of form? about the forms philosophy can take?—which has to do with asking how a comic strip relates to that very “reality” that Fanon urges us to refuse. The philosophical and formal question is how a comic strip relates, then, to something that so profoundly is that it’s the contours of the Earth we stand on; and this is thus a question about the relationship between the fantastic and the real.

The sage Emil Kópen replies to the New Zealander’s question,

They [comic strips and maps] are the same thing; using all of language—not only words or pictures. . . . Maps are of two kinds. Some seek to represent the location of things in space. That is the first kind—the geography of space. But others represent the location of things in time—or perhaps their progression through time. These maps tell stories, which is to say they are the geography of time. . . . I have begun to feel that stories, too, are basically concerned with spatial relationships. The proximity of bodies. Time is simply what interferes with that, yes? . . . The things we crave are either near us or far. Whereas time is about process. I have lived many years and I have learned not to trust process. Creation, destruction. These are not the real story. When we dwell on such things, we inevitably lapse into cliché. The true drama is in these relationships of space.28

The translator, perhaps speaking for the New Zealander, perhaps raising her own objections, interjects, “But a flame, even a touch, are processes, not things.” Kópen answers, “But behind such processes, there is a stillness; and in that quiet exist spatial relationships which transcend time.”29

This is a reckoning of comics form—which we must understand as therefore an account of reading/seeing comics, of the reader’s active engagement with the formal properties of the comics and their contents—that may perhaps verge on the megalomaniacal or the messianic, appearing to claim for comics what only our guesses of divine or transuniversal perspective could boast. Nevertheless, combining Horrocks-via-Kópen with Spiegelman, McCloud, and Chute, we can surmise that the most conventional of comics storytelling devices need not lead to the most conventional representations of blackness: if comics form does not conform to linear temporality, if comics transcend time, if comics may delve beneath process to find stillness, then as a form, comics offer, and should indeed entice and encourage, opportunities to knock that devil history off his horned feet.

Comics’ spatialization and thus transcendence as well as layering of time, comics’ disarrangement of even the linearity of the sequence on which its structure relies, the queer temporal indeterminacy of the way comics tell stories and the way comics compel reading, all are useful tools for fantasy-acts. Comics can make historiography itself cartographic—what the reader and the comics creator both are enabled to do is to leap not just buildings but epochs, to scramble cause and effect across time. Rendering historiography in the mode of cartography can be aimed at Fanonian “disalienation,” can bring forth keys for unlocking the ironbound “tower of the past.” And at the same time as one can come to comics with such goals in mind, the very reading of them can provide a demonstrative example, a “map,” that unspools in the readers’ minds the possibility of refusing reality.

As we know, such moves are entirely precedented in African American and African Americanist letters.

See Ashraf Rushdy’s observations of how neo-slave narratives (the novels by African American authors that thematize slavery from the 1970s to the 1990s) repeatedly return to the trauma-curing tactic of reimagining traumatic events in a manner that empowers the traumatized:30 For example, in Gayl Jones’s Corregidora (1975), the protagonist Ursa’s inheritance of the intractably traumatizing legacy of her foremothers’ rape and forced incest at the hands of a Brazilian slave master—Ursa’s own great-grandfather—imprisons Ursa in a kind of stuttering replay of her foremothers’ lives. This cycle breaks when Ursa begins to reimagine the stories of her foremothers’ assaults with a recognition of how pleasure as well as pain inhere in those experiences, and in her reimagination, she assumes a position to choose which (pleasure or pain) she desires. And in David Bradley’s The Chaneysville Incident (1981), a folktale of fugitive enslaved black people who were reported to have killed themselves to avoid being recaptured is transformed from a story of despair and futile defiance to—from a West African cosmological point of view, adopted by the novel’s narrator—a story of joyful reunion with beloved ancestors and a figurative return to Africa, once the narrator, a historian, reimagines the folktale as his own version of “real” history.

See also Saidiya Hartman’s pathbreaking essay “Venus in Two Acts” (2008). Hartman calls for historians of enslavement to confront the violent erasure in the historiography of the slave trade and slavery of enslaved black women’s consciousnesses and being (such erasure being a foundational act of the trade, the practice, and the historiography that accounts for it) via the adoption of “critical fabulation,” a practice that turns a gimlet eye to the authoritative claims of orthodox historical method:

Is it possible to exceed or negotiate the constitutive limits of the archive? By advancing a series of speculative arguments and exploiting the capacities of the subjunctive (a grammatical mood that expresses doubts, wishes, and possibilities), in fashioning a narrative, which is based upon archival research, and by that I mean a critical reading of the archive that mimes the figurative dimensions of history, I intended both to tell an impossible story and to amplify the impossibility of its telling, . . . laboring to paint as full a picture of the lives of the captives as possible. . . .