CHAPTER 6

Shot Down

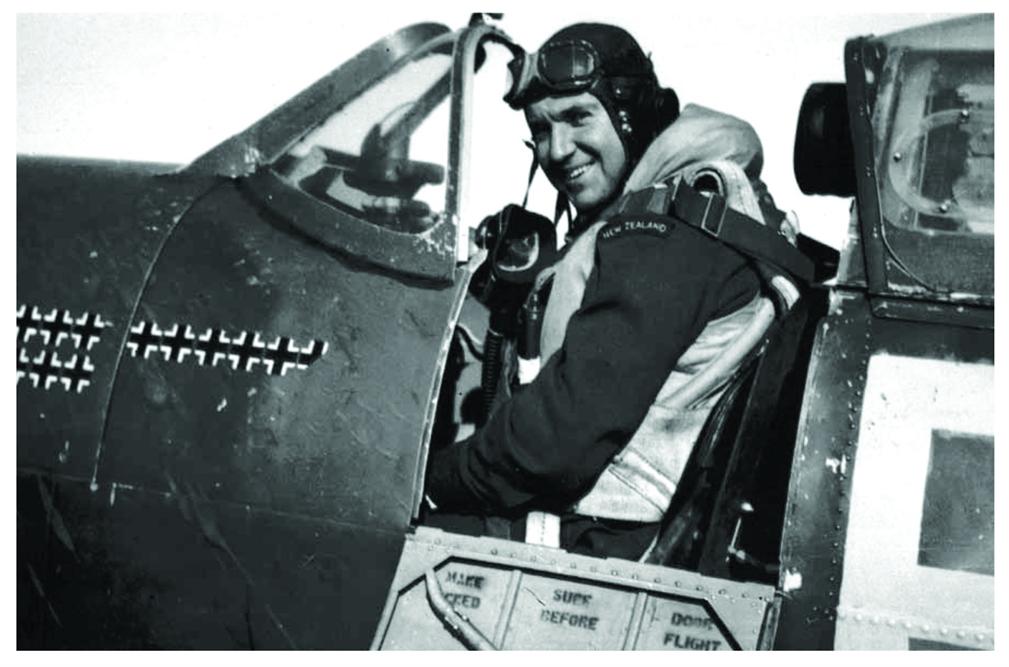

The 15 August opening southern sallies caught New Zealander John Gibson with cards in hand learning the intricacies of bridge at 501 Squadron’s forward coastal airfield at Hawkinge.[1] The Hurricanes were dispersed around the all-grass airstrip and the pilots clustered in battered chairs by their temporary canvas accommodation. Chess, reading and card games were distractions and time-fillers before the inevitable call-up. The first indication that something was afoot came at 10.45a.m. when thirty or so aircraft were picked up by radar and plotted heading for the English coast from Cap Gris Nez. Along with a handful of other units, 501was sent aloft to patrol the Hawkinge airfield. ‘Gibbo’ was leading a section in his second sortie of the day.[2] With seven confirmed and two unconfirmed victories, plus seven damaged enemy aircraft to his name already, the former rifle-shot champion of New Plymouth Boys’ High School was already an ace and leading member of his unit.

Gibson spotted twenty incoming Ju 87s and immediately pushed his Hurricane to intercept with two wing-men in his wake. The slow Stukas were no match and the New Zealander and his compatriots took out one apiece. Over the radio the squadron received a hasty recall as another formation of Ju 87s was in the process of bombing Hawkinge. But on this occasion the Stukas proved they were not without defences. Although Gibson was able to wing a Ju 87, he was badly damaged in the process. The rear gunner had fatally wounded his Hurricane over the town of Folkestone and Gibson was forced to bale out at low altitude. Unaware that the New Zealander had vacated his machine, one of his fellow card players gleefully asked Gibson via the radio: ‘Did you get one? By the way, three no trumps doubled! See you back at base.’

The late afternoon forays in the south drew in the day’s biggest clutch of Anzacs. A large force including forty Ju 87s, twenty Me 110s and a massive escort of sixty Me 109s was making for Portland. To counter this, Fighter Command put up three squadrons. Around 5.00p.m. the Hurricanes of 87 and 213 Squadrons were vectored to break up the dive bombers and scatter the Me 110s, while the Spitfires of 234 had the unenviable task of taking on the numerous Me 109s. In all, only thirty-six fighters stood in the way of the 120 intruders. Of the RAF airmen at least eight—that is, a quarter—were Australians or New Zealanders.

The dapper Squadron Leader Terence Lovell-Gregg led 87 Squadron. The unit had just finished rebuilding from its fall-of-France hammering and, because of its westward location at Group 10’s Filton sector airfield at Exeter, it had seen little action thus far. Like the other New Zealand Squadron Leader at Exeter, McGregor, Lovell-Gregg was an early entrant into the RAF. The Nelson College graduate was academically brilliant and only denied entry to the University of Otago’s medical school due to his youth. He turned his hand to flying and became one of the youngest qualified pilots in Australasia. Though considered too scrawny for air service by the New Zealand medical examiner, he made his way to England and entered the RAF in 1931.[3] In spite of operational experience in Iraq and Syria, most of his pre-war service was as an instructor. Sporting a carefully groomed moustache and slicked-back hair, Lovell-Gregg had been keen to resume operational duties when war broke out. He was appointed commanding officer in late July 1940. The decision was a popular one and the well-liked Lovell-Gregg was simply known as ‘Shovel’.

Recognising his lack of recent operational experience, the ‘old man’ of the squadron (at twenty-eight years of age) often relinquished operational command in missions to younger combat-hardened officers.[4] On this occasion his right-hand man was fellow New Zealander Flight Lieutenant Derek Ward.

After lunch, 87 Squadron pilots had taken to their motley collection of chairs under the hot August sun. In addition to ‘Shovel’ and Ward, the 87 crew boasted another Kiwi, Wellingtonian Kenneth Tait. Like Ward, Tait was a veteran of France, already able to catalogue a series of death-defying adventures including having crashed on the wrong side of the Maginot Line on one occasion, and waking to the sound of artillery shrapnel ripping his tent to pieces on another. His escape from France was widely reported in newspapers and chronicled his inspired requisitioning of a Dutch aircraft and alighting in England near naked, lacking a shirt, scarf and flying boots.[5] In the mass exodus he had reluctantly abandoned his personal effects.

The inevitable warning phone call came through and pilots who had been sunning themselves tugged on their shirts, along with the obligatory yellow Mae West. Twenty-five minutes later the operations bell harshly broke the reflective calm and sent Tait and others scampering to their aerial mounts, encouraged by one of the pilots’ dogs, a barking bull terrier named Sam.[6] Not far behind was Exeter’s other Hurricane unit, the McGregor-led 213 Squadron.

‘Shovel’ sighted the enemy ten miles south-west of Portland. The intruders had already been engaged and the area of combat resembled a tall cylinder stretching from 12,000 to 16,000 feet within which an angry swarm of bees engaged in a life-and-death dance; at the lower altitudes the Ju 87s were formed into defensive circles with escorting Me 110s at their shoulders, and in the upper reaches prowled packs of Me 109s. It was a jaw-dropping sight for the relatively unpractised Lovell-Gregg. Nevertheless, swinging his Hurricane over into the fray he yelled the traditional ‘Tallyho’ over the radio. Ward followed:

The interception had broken into individual dogfights with the RAF pilots outnumbered. Tait was almost immediately attacked as he ‘waded into a circle of 110s’, but managed to turn the tables on the enemy pilot and gave him a short burst.[8]

In the breathless minutes of combat Tait did his best to protect his fellow airmen, while 87 and 213 Squadron pilots returned the favour, prying loose enemy machines from his tail. His closest call with the enemy came in the dogfight’s latter stages when he climbed to 9000 feet to join a formation of eleven Hurricanes ‘only to find they were Me 109[s]’. Tait beat a hasty retreat, leaving the Messerschmitts to the Spitfires of 234.

In the battles of August, 234 Squadron was heavily stacked with Anzacs. Nicknamed the ‘The Dragons’ and operating under the motto Ignem Mortemque despuimus (‘we spit fire and death’), the unit was based at Middle Wallop. Its cadre of airmen included the Australians Flight Lieutenant Pat Hughes and Vincent ‘Bush’ Parker. The New Zealanders were Cecil Hight and Lawrence. The fight was furious and costly. The fifty enemy single-engine fighters simply overwhelmed the squadron. Of the Anzacs, only Hughes was able to take down an Me 109 and share in the destruction of another. Hardy and Parker were less successful, struggling to avoid cannon and machine-gun fire. Both pilots were hit and wounded. The mêlée took Hardy well out over the Channel. Low on fuel, his only hope was a safe landing on the wrong side of the Channel. Parker’s engine was mangled by cannon fire and he was forced to bale out over France. While no combat report remains for the Southlander, Lawrence, he did survive the lopsided struggle, which is more than can be said for Hight. The car salesman from Stratford, New Zealand, was fatally struck and the Spitfire crashed in the city of Bournemouth.[9] The Dragons were fortunate not to lose more.

Anzac POW

Parker was one of three Anzacs to be taken into enemy captivity during the Battle of Britain. While little is known about the capture and subsequent imprisonment in October of New Zealanders George Baird and Sergeant Douglas Burton, Parker’s escapades were the stuff of Boys’ Own stories.[10] An English immigrant from Townsville, Queensland, ‘Bush’ Parker briefly resided in New Zealand, training as a magician with well-known entertainer and conjuror of the pre-war period Leslie George Cole, self-titled ‘The Great Levante’. It was here that Parker perfected the sleight of hand and the mysteries of ‘escapology’ that would increasingly frustrate his German captors.[11]

At Stalag Luft I at Barth on the Baltic coast, Parker took part in numerous tunnelling efforts and assisted other airmen in escape attempts. He was particularly renowned for the compasses he manufactured from slivers of steel extracted from razor blades and rubbed against a magnet he had stolen from a camp loudspeaker. These were used in at least one successful ‘home run’.

In the first of his own three attempts, he was recaptured and thrown into ‘the bunker’ for a fourteen-day stint of isolation. His second attempt was a reworking of one that had recently seen a would-be escapee shot as he crawled across the snow-blanketed playing field camouflaged by a white sheet. The field was swept by the eyes and searchlights of two guard-towers and the wire fence was patrolled by armed guards. Parker’s plan was to join in a rugby game and, when a scrum was formed over a furrow in the snow, he would lie in this and be covered with more snow by the players. Clad in ‘two pairs of trousers, two jackets, four pairs of socks and numerous layers of underclothing’, the young Parker waited for an opportunity to make for the fence, cut his way through and make good his escape. ‘Those six hours were an eternity; my legs grew wet, ached and became numb; I couldn’t move...’

His final attempt was a bold impersonation of one of the camp’s ‘ferrets’, Unteroffizer Piltz, whose main vocation was the sniffing-out of prisoner tunnels and escape plans. Clad in dirty overalls, wearing a security personnel-style cap and sporting a ‘torch’ cobbled together out of painted Red Cross tins, he successfully navigated his way through two barriers of sentries. Unfortunately, Parker was met in the woods by the very person he was impersonating: Piltz.[13] The young Australian was promptly arrested and awarded fourteen more days of punishment in the cells for his audacious efforts.

Parker was transferred briefly to Stalag Luft III at Sagan, scene of two famous escapes later dramatised for the movie-going public as The Great Escape and The Wooden Horse, before entering, in May 1942, his final residence at the Second World War’s most famous POW camp Oflag IV-C, popularly known as Colditz Castle.

In surviving photographs from Colditz, Parker smiles impishly—looking much younger than his twenty-two years. He joined a stellar cast of inmates at what the Germans designated a ‘special camp’. Although sprinkled with men with family ties to Allied governments and the British Royal Family, the great majority of the inmates were hardcore recidivist escapers from other camps. Perched on a cliff overlooking the town, the sixteenth-century castle was considered escape-proof by the Germans—apparently an ideal holding pen for prisoners who needed to go cold-turkey on their escape addiction. The inmates had other ideas, and with such a concentration of incurables, Colditz saw more successful escapes by officers than any other German prison.

As an inmate, Parker made at least two unsuccessful bids for freedom and aided and abetted many others thanks to his ability to pick the ‘unpickable’ locks of the castle.[14] Coat hooks, iron bed framing and coal shovels were transformed into keys of various shapes and sizes. Combining a magician’s sleight of hand and his eventual collection of over 100 keys, the Australian proved a handful for the Germans. A fellow inmate recalled how Parker on one occasion handled with great aplomb a surprise search by the Germans.

Parker was able to gain access to some of the most valued areas of Colditz, including the parcels’ office and the attics. The former furnished the prisoners of war with everything from maps to radio equipment, while the latter enabled them to listen undisturbed to Allied broadcasts and construct the famous but never used Colditz glider. Although a skilled, if relatively inexperienced, combat pilot, Parker was blessed with considerable nonaviation-related talents that severely tested the patience of his German captors. By the end of the war he had probably caused the enemy more headaches as a prisoner than if he had been flying.

Closing the Greatest Day

The early evening brought with it the final day’s action for the Anzacs Francis Cale, John Pain, Irving Smith and the deadly pairing of Deere and Gray. Cale’s 266 Squadron was ordered to patrol over Dover and at 6.30p.m. encountered bombers and Me 109s to the south-east. The eight Spitfires were able to separate some Ju 88s from the fighters and engage the quarried prey. The exuberant Cale, educated at Guilford Grammar School, Perth, was caught by an Me 109 and shot down, baling out at low altitude.[16] His body was recovered from the River Medway the following day.

At 7.00p.m. 32 Squadron encountered Do 17s and Me 109s at 19,000 feet. The Scotland-born Queenslander Pain was jumped by six Me 109s. The fresh-faced nineteen-year-old pilot was in his first real action, flying a machine he had only become acquainted with over the previous four weeks.

His saving grace was that he was a natural aviator and genuine flying prodigy. A pilot at the age of fifteen years and winner of a highly contested flying scholarship in his latter teenage years, Pain used his full evasive manoeuvre repertoire and, with a measure of good fortune, not only avoided being cut to shreds but turned on his attackers. As the fighters flew past him, almost netting him in strings of tracer fire, Pain eased his aircraft in behind the last Me 109. As it turned in front of him, he fired: ‘Saw smoke coming from the enemy. Gave him another short burst and smoke increased.’[17] In the end he accounted for a Ju 88 and was able to claim a probable on the fighter. In his log-book he simply jotted ‘Nasty Blitz on Croydon attacked by six Me 109’s.’[18]

One of the last interceptions was to be flown by 54 Squadron. Both New Zealanders hoped it would be uneventful and Gray was heard to exclaim he was ‘dying for a beer, a good meal and bed’, when news of the raid broke.[19] Forming up over the French coast was the day’s last big raid. The clanging warning bell heralding the order to scramble chased away thoughts of beer and bed. Deere and Gray pushed their Spitfires to maximum speed and made a dash for the coast with seven other fighters in attendance. Through the radio chatter the controller vectored the pilots onto the intruders, which were about to make landfall close to Dover at 20,000 feet. The pilots of the squadron added 5000 feet to the estimation just to be sure and gained an advantage over the enemy. The enemy bombers were clustered together with fifty-odd fighters layered overhead. Surprise was complete and the Spitfires fell among the Me 109s.

Engaging the enemy at the same time was Smith. The good-natured industrial painter from Auckland was flying with 151 Squadron’s Hurricanes en route for a very large formation of fighters. He had only joined the Squadron four weeks earlier and was now in the thick of the fighting and about to cap off a remarkable baptism of fire. Based at North Weald, the squadron had seen heavy action over the Thames Estuary in July and was now operating further south near Dover. Like many of Park’s squadrons in this phase of the battle, Smith’s squadron carried out most of its operations from a forward satellite airfield. In this instance it was the all-grass Rochford, on the coast north of the Thames Estuary.

After barely four hours’ sleep at North Weald sector airfield, Smith and his fellow airmen would be awoken around 2.30a.m. and after washing down an egg or two with a cup of tea would be airborne by 4.00a.m., making their way to Rochford. Here they cohabited with two Spitfire squadrons and, like Gibson at Hawkinge, the men had only light tents as accommodation and made do with scrounged seating and tables from the local town. All three squadrons utilised only one field phone, so that when it rang there was the habitual start and then the anxious pause before the waiting pilots discovered who was being scrambled. At dusk the Hurricanes could be back at North Weald for servicing. Getting a decent meal could be a hit-and-miss affair. At Rochford, food was delivered to the pilots in boxes and it was possible in a heavy day’s action to miss these and remain unfed until returning to North Weald, and even there the cooks, accustomed to a set regime, had to be cajoled into conjuring up a boiled egg.

Conditions could vary considerably from airfield to airfield, due in good part to the quality of the station commander. Some were extremely diligent in looking after their airmen’s needs, but others less so. Miller and Curchin found 609 Squadron was not well looked after at Warmwell, Dorset, where the accommodation was so run-down that the bulk of the airmen preferred to sleep in the dispersal tent lacking running water and toilets. Pilots were forced to sleep in dust-laden blankets. Meals were problematic too. Civilian cooks refused to rise early enough to feed the pilots before they departed, and the entirely unsympathetic station commander, frustrated that the airmen were not appearing in a timely manner for meals, ordered the mess to be locked outside of the dictated meal times. As the Australians’ incredulous squadron leader later sarcastically fumed, ‘All our efforts to get the Luftwaffe to respect ... meal times having failed, deadlock occurred.’[20] Even after the 609 pilots intercepted a raid on the Warmwell facilities that doubtless not only saved hangars and aircraft but also unhelpful mess personnel, the station commander remained unmoved and, consequently, pilots went without hot meals. In the end, RAF staff stepped in with copious boxes of provisions which the hungry pilots turned into dubious al fresco delights.

At Hornchurch, conditions were far more to the liking of pilots. The benefits of a good and loyal cook were appreciated by the airmen; 54 Squadron was fed and watered by Sam, whom Deere described as a ‘tyrannical house master’ but a very popular mess chef. On one occasion in the campaign the unit’s pilots had returned late and the famished airmen made a beeline for the officers’ mess. A senior pilot was surprised the head cook was still on duty and had not left the late-night offerings to his lesser minions. ‘Sir, you know that I never go off duty,’ retorted Sam, ‘until my pilots have returned from operations and are properly fed.’ The homely comforts of bacon and eggs or, as on this occasion, roast beef accompanied by brussels sprouts, served up by their caring mess cook were roundly appreciated by the fatigued pilots.

Flying out of Rochford, in his third and final operation at 7.00p.m., Smith latched on to an enemy fighter. His fire was accurate and he followed the wounded machine down to 5000 feet, at which point he broke away observing the Me 109 heading down in a vertical spin.[21] A single victory would have been an achievement in anyone’s books, but Smith had already been in two other combat operations, in one of which he had destroyed an Me 109 and damaged another. A total ‘bag’ of two victories and a wounding was a considerable feat for such an inexperienced pilot officer. Smith was, however, in no mood to celebrate and scrawled in his after-action report that the squadron had lost three pilots in the last engagement.

Meanwhile, Deere’s initial attack was truncated when he came under fire from a German pilot. Evasive action shrugged off the attacker and he was soon on the tail of two enemy fighters fleeing east to France. The Luftwaffe pilots had capitalised on the Me 109s’ speed in the dive and stretched out a frustrating lead. Determined, the New Zealander nudged his Spitfire into one of the Me 109’s blind spots just below the tail. Edging closer in the downward run he was about to open fire at 5000 feet when light cloud cover intervened, prolonging the chase. Eventually shedding the cloud cover and basking in the full sunlight, Deere belatedly realised with horror that he was now crossing the French coast. Thinking he was safe within the confines of France, one of the airmen rolled gently left to land at the local airfield. He was blissfully unaware that he had been shadowed all the way home and Deere’s short depression of the firing button was immediately effective and the aircraft dived to its death. The second machine was also hit with glycol and smoke belching from the engine, but Deere was unable to finish his handiwork. The odds were not in his favour as he found himself in an area thick with prowling German fighters. Almost immediately five turned in to snare the wayward Kiwi. ‘You bloody fool,’ he muttered.[22]

He was now consumed with two tasks: avoiding the fighters and edging closer to the English coast. The fly in the ointment was the fact the enemy’s speed and direction would see them intercept Deere long before he reached the white cliffs of Dover. Two of the fighters soon bore down on the sprinting New Zealander, forcing him to take evasive action in a series of vicious turns. ‘I knew that before long they would bring their guns to bear ... with each succeeding attack I became more tired, and they more skilful.’ Machine-gun fire homed in on the Anzac, shattering the canopy and disintegrating the instrument panel. Only the armadillo-like armour plate at his back saved him. ‘Again and again’ they came at the fatiguing Deere, and ‘again and again I turned into the attack, but still the bullets ... found their target’. The damaged Merlin engine broke into a death rattle that shook the light-framed fighter. Oil slithered over the windscreen and he turned for Dover violently snaking the Spitfire from side to side to present as difficult a target as possible. The coast loomed large now and, unlike Deere, the Luftwaffe airmen astutely reckoned that the chase had already taken them too close to a potential ambush and they promptly broke off the enterprise, pointing their Me 109s towards France.

At 1500 feet over England the engine caught fire and Deere was forced to turn the Spitfire on its back to facilitate a gravity-aided escape. Unfortunately, the machine was reluctant to allow Deere’s emancipation and the nose dropped, angling the Spitfire into a vertical free fall. As if grappled by an unseen hand he was pushed against the fuselage directly behind the cockpit, pinned like an insect in an entomologist’s display case. Tensing his muscles he purchased enough distance between his spine and the fighter for the wind to pluck him away. His wrist roughly struck the tail as he pulled the ripcord at a perilously low altitude. ‘I just felt the jerk of my parachute opening when my fall was broken by some tall trees.’

Miraculously his ‘only injury was a sprained wrist’.[23] Worse for wear was the plum tree. The farmer gave the New Zealander a regular tongue-lashing. The fruit-laden tree was the only one unharvested—deliberately saved for a future plucking. Deere cast the entire crop.[24] An ambulance delivered him to East Grinstead hospital. X-rays revealed no broken bones but the pain was sufficient for Deere to receive suitable sedatives and sleep the night away at the hospital. The next day, brandishing a plastered wrist, he slipped back into Hornchurch to find that Gray had been awarded a DFC, news the latter had received alongside a good meal washed down with a beer.

Caterpillar Club

Deere’s survival was due to good luck and a well-maintained parachute. A few pilots tipped their packers the princely sum of 10/-, not an inconsiderable amount, nearly a fifth of their weekly pay.[25] Fighter Command airmen recognised the importance of a well-maintained silk saviour and considered the money small change, given its life-preserving properties. The pilots of the Great War were not so fortunate and, as their machines became flying crematoria, they sometimes resorted to a pistol to hasten their exit from the excruciating pain of fire. In marked contrast to the pilots of this earlier era, approximately two-thirds of Battle of Britain airmen in stricken machines survived to tell the tale thanks to this inter-war development. Those aviators saved by the parachute were eligible for entry into the Caterpillar Club, named after the source of the silken thread parachutes were manufactured from. As ‘Bush’ Parker stated simply in his August 1945 letter applying to join the Caterpillar Club: ‘one of your parachutes saved my life.’[26]

That is not to say that baling out was not without it perils, as the loss of Cale to the River Medway grimly attested. In the first instance, the canopy of a fighter travelling anything in excess of 180 mph would not open. In addition, should the groove in which the canopy slid be damaged, the airman’s last resort was a crowbar stored at the pilot’s side. Not a heartwarming prospect when some pilots estimated that you had barely eight seconds on a good day to evacuate a burning fighter. Further, as Deere’s escapade demonstrated, there was always the possibly of striking or snagging the tail section of the fighter. If the airman was knocked unconscious in the process the parachute would remain forever unopened.

Where the pilot landed was also an important consideration. Terra firma was clearly preferable to a dip in the drink. Though it depended on which side of the Channel the evacuation had taken place, a point well understood by the few pilots like Parker who baled out over occupied France and only found freedom in May 1945 when he was liberated. Even baling out over ‘Blighty’ was no guarantee of a welcome reception, as Olive had both experienced and observed. After his first kill on 20 July, he had flown home with the intent of seeing what had become of the fellow pilot who had popped out of his aircraft like a ‘cork from a champagne bottle’. He located the parachute in a field of ripe wheat:

In the early weeks of the Battle of Britain, fuelled by stories of German paratroop-led assaults in Denmark, Norway and Belgium, members of the Home Guard, according to the Queenslander, treated all parachutists as either hostile or ‘excellent random target practice’. Olive was not about to let a fellow airman suffer the ignominious fate of being killed by the Home Guard and made a series of low passes over the ‘two intrepid defenders of the realm’, cursing the fact he had no ammunition left to fire off a cautionary round or two in their direction. His only hope was that he had done enough to force the trigger-happy farmers to take cover, allowing the pilot sufficient opportunity to make good his escape. Finally, for an airman to have even a chance of survival after exiting an aircraft, the jump needed to take place at a sufficient altitude to facilitate the optimal deployment of the parachute.

If Deere’s 15 August escape from his Spitfire was dangerous, Gibson’s earlier example was at first flush downright reckless because it had been executed at an extremely low level. The citation for his DFC explained the significance:

What the citation did not mention was Gibson’s concern for his footwear. ‘I had a brand-new pair of shoes handmade at Duke Street in London. We used to fly in a jacket, collar and tie, because we were gentlemen.’[29] Fearing a sea landing, and hence damage to his shoes, he had the presence of mind to take them off and drop them over land before his parachute carried him over the Channel. Remarkably, an astute farmer sent them on to the base—a greater reward than the DFC in the mind of the New Zealander.

Pilots who accumulated a high number of combat sorties during the campaign were more than likely to have made at least one jump, and many made more during the conflict. In 501 Squadron, over the course of the campaign some sixteen pilots either made forced landings or baled from their machines.[30] The pilot with the dubious honour of leading the rankings was ‘Gibbo’, who gathered bale-outs like prized possessions. In addition to a crash-landing in France in the May battles and landing in a bomb crater in August, Gibson would bale out of his Hurricane on four occasions—twice over the Channel. He was pretty pragmatic about his approach to exiting his machine:

Having nearly ‘bought it’ at Folkestone, he secured a phone at Dover and rang through to the 501 lads and nonchalantly informed them that someone else should pick up his cards and play his hand as he would be late home. The lost Anzacs—Cale and Hight—made no phone calls.

Neither would Lovell-Gregg. The experienced pilot, but inexperienced combat flyer, was seen descending in a blazing Hurricane by a local farmer. In an interview years later he told of Lovell-Gregg’s demise:

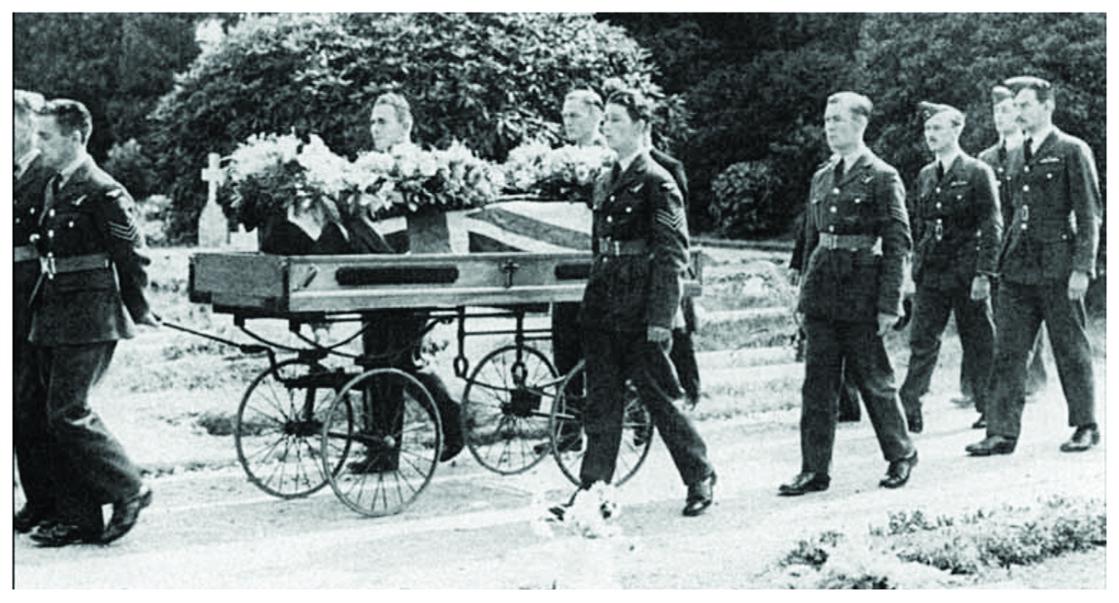

Three 87 Squadron pilots, including the Kiwis Ward and Tait, flew to the funeral, the only mourners in attendance at his final resting place, the Holy Trinity Church, Warmwell.

Gratitude

As soon as the day had concluded, the tallies from RAF and Luftwaffe pilots were totalled. Fighter Command’s men claimed a whopping 182 German machines destroyed while the Luftwaffe was publishing 101 victories. In fact Göring had lost some 75 machines and Dowding 34 fighters in aerial combat. The Germans were facing extreme difficulties as the operational limits of the Ju 87 and Me 110 were exposed. The Luftwaffe Commander-in-Chief was now of the opinion that the Stuka would need a three-fighter escort in future and that given the losses in dive-bombers and, even more significantly, the apparent lack of rewards for raids on radar stations, perhaps these should be curtailed. The success of the RAF was also evident in the fact that even the twin-engine bombers were in need of at least two fighters each to avoid crippling losses.

The result was twofold. On the one hand this meant that the number of bombers that could be used in a raid was limited to the number of fighters available for escort duties. Although 1786 Luftwaffe sorties were undertaken, only 520 were by bombers.[33] Thus some fifty per cent of Kesselring and Sperrle’s bomber fleets were unable to be used in the day’s assault on the grounds that adequate fighter protection was not possible. On the other hand, orders to protect the bombers greatly frustrated German fighter pilots accustomed to more freedom of action. The day’s grim results led German airmen to dub it der schwarze Donnerstag (Black Thursday). To make matters worse for the Luftwaffe fighter pilots, they were now ordered to undertake their escorting duties at the same altitude as the bombers in order to more directly engage the intercepting fighters. This meant the Me 109s would be operating from between 12,000 and 20,000 feet. The result was that the RAF fighters would now meet the enemy at their optimum altitude. Park’s strategy of concentrating on the bombers was working.

Given the hammering of 15 August it was remarkable that the Germans continued the assault with similar intensity. Aside from a brief hiatus on 17 August, the Luftwaffe undertook some 1700 sorties each day, but Fighter Command was there to meet them every time. Pilots and ground crew were all under considerable strain during this phase of the campaign. By 19 August, Fighter Command had lost ninety-four pilots either killed or missing, and the sixty or so wounded further thinned the ranks. In regards to aircraft, Dowding had lost 183.[34] On the German side 367 machines had been destroyed at the hands of the RAF.

In the lull, Churchill broadcast his thanks to the men involved in the air battle across Bomber, Coastal and Fighter Command:

Deere was listening to the BBC with one of his mates, Gribble. ‘It’s nice to know that someone appreciates us, Al. I couldn’t agree more with that bit about mortal danger, but I dispute the unwearied.’[36] ‘Despite the flippancy of George’s remarks,’ recalled Deere years later, ‘such encouraging words from a most inspiring leader were a wonderful tonic to our flagging spirits. To me, and indeed I believe to all of us, this was the first real indication of the seriousness of the Battle, and the price we would have to pay for defeat. Before, there was courage; now, there was grim determination.’

Air Vice-Marshal Keith Park (Air Force Museum of New Zealand) (Note: This and some other photographs in the following pages post-date the Battle of Britain.)

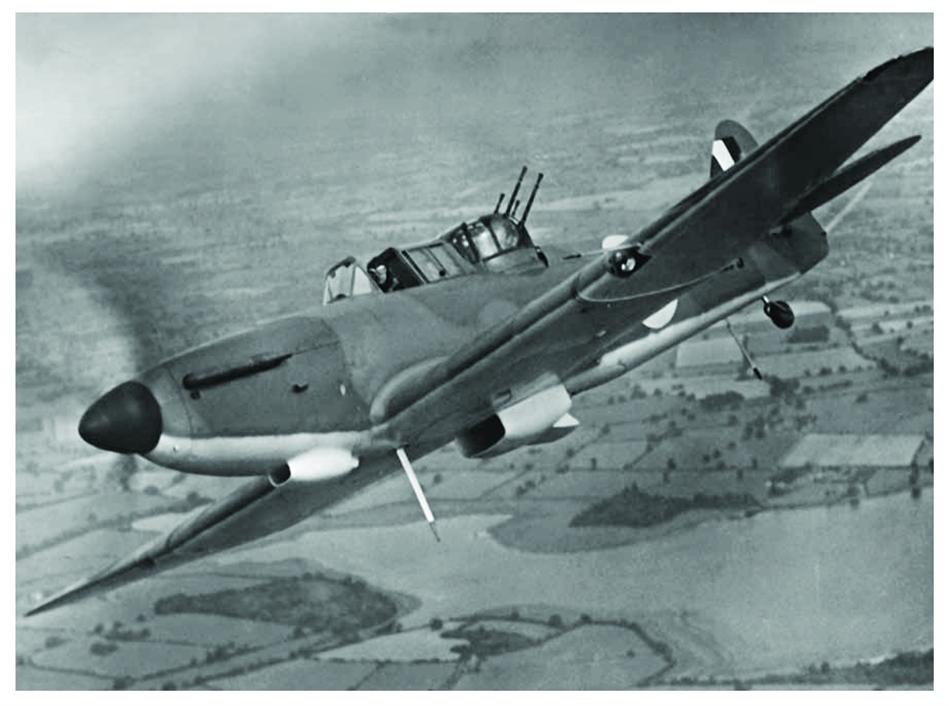

Hawker Hurricane (Imperial War Museum)

Supermarine Spitfire (Imperial War Museum)

Alan Deere (Air Force Museum of New Zealand)

John Gard’ner (right) with his gunner (Suzanne Franklin-Gard’ner)

Boulton Paul Defiant (Air Force Museum of New Zealand)

New Zealanders

Keith Lawrence (Keith Lawrence)

Colin Gray (Air Force Museum of New Zealand)

Brian Carbury (David Ross)

Bob Spurdle (Air Force Museum of New Zealand)

John Fleming (Max Lambert)

John MacKenzie (Air Force Museum of New Zealand)

Australians

Gordon Olive (Dennis Newton)

John Crossman (Dennis Newton)

Clive Mayers (www.bbm.org.uk)

Pat Hughes (Dennis Newton)

Stuart Walch (Dennis Newton)

Richard Hillary (Dennis Newton)

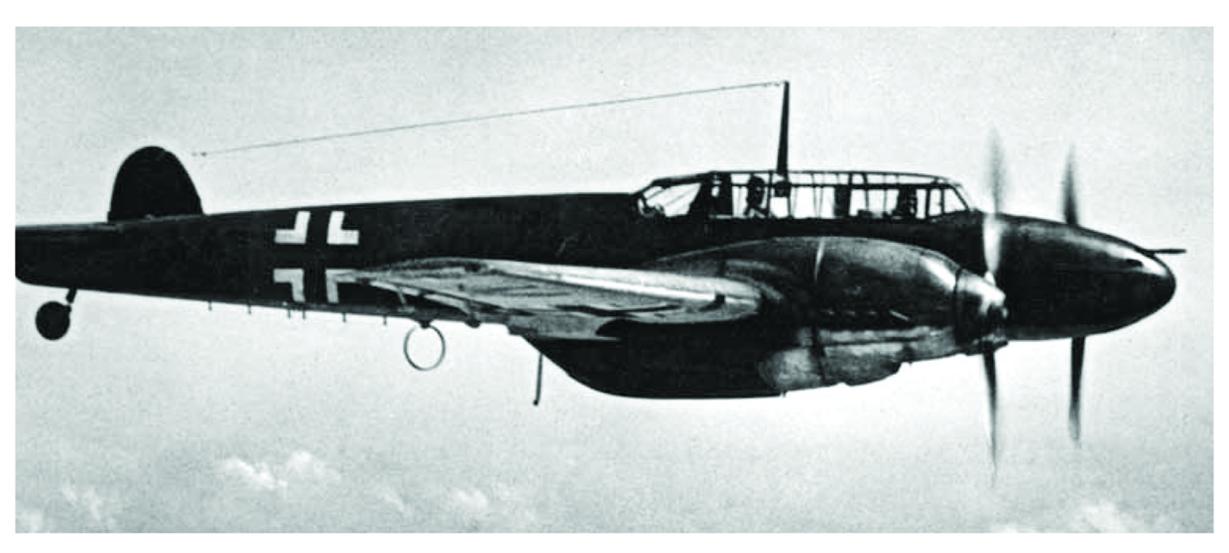

Messerschmitt Me 109 (Air Force Museum of New Zealand)

Messerschmitt Me 110 (Air Force Museum of New Zealand)

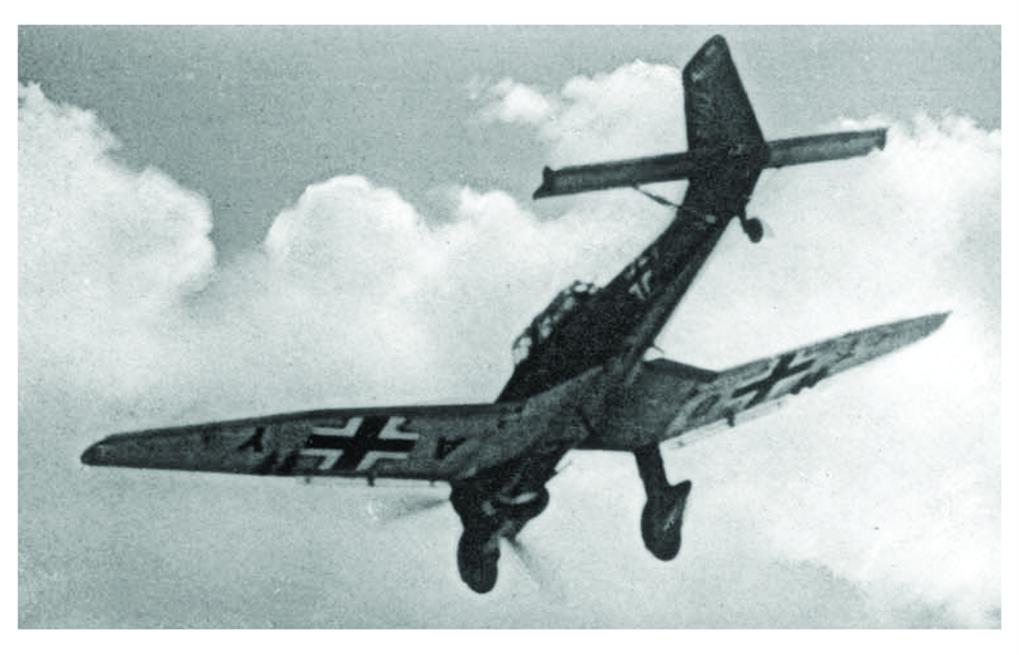

Junkers Ju 87 Stuka (Air Force Museum of New Zealand)

Flanked by fellow pilots of 92 Squadron, James Paterson cuts a ‘trophy’ from a bomber he has just shot down (Jim Dillon)

Cecil Hight’s funeral procession (Ray Stebbings)

Vincent Parker (standing, second left) with other Australian officers in Colditz Castle (Colin Burgess)

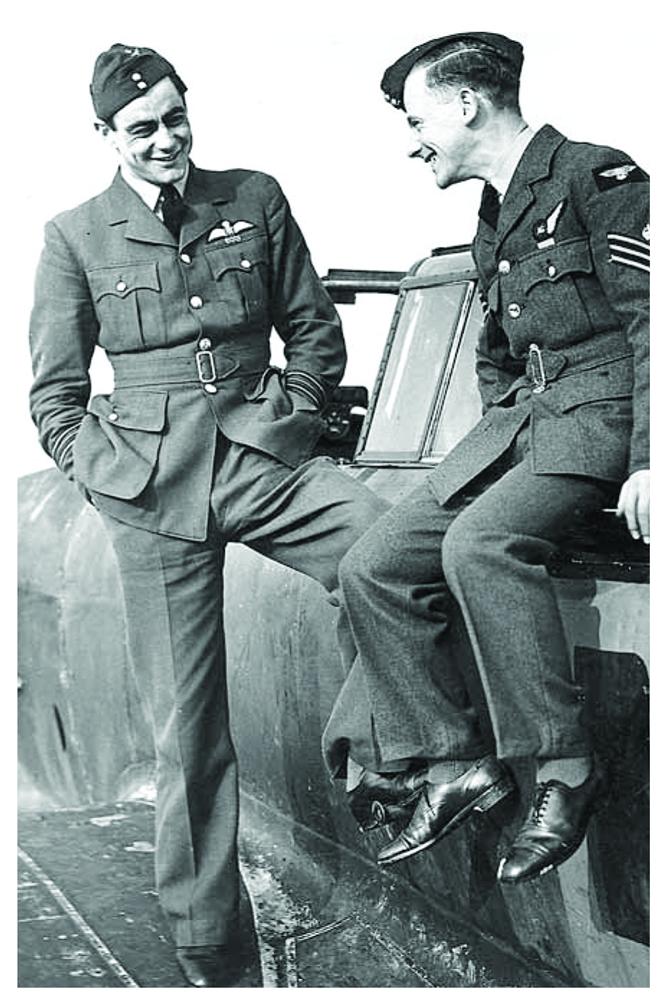

Irving Smith (right) in conversation with a non-commissioned officer (Rupert Smith)

Wilfred Clouston (right) with mechanics (Richard Clouston)

John Gibson (Air Force Museum of New Zealand)