CHAPTER 1

Barbering for Freedom in Antebellum America

IN his 1855 novella Benito Cereno, Herman Melville provides a vivid literary evocation of antebellum grooming. This tale about a revolt aboard the slave ship San Dominick is woven around the real-life American captain Amasa Delano's account of an actual 1805 event.1 To heighten the symbolic meaning of the story, Melville changed the name of the ship from The Tryal to San Dominick in reference to the 1790s slave revolt in Saint Domingue. In the story, Delano boards the seemingly distressed Spanish slave ship to find a dejected and bewildered captain, Benito Cereno. After Delano leaves the ship and Cereno jumps after him, Delano learns that the slaves controlled the ship and Cereno the entire time. Moreover, Cereno's body servant, Babo, acts as the leader of the revolt.

In the figure of Babo, Melville presents the popular antebellum perceptions of loyal black servants and their potentially hidden agendas to strike against their owners. On the one hand, Babo is presented as the cheerful servant attending to his master. “There is something in the negro which, in a peculiar way, fits him for avocations about one's person,” the narrator interjects. “Most negroes are natural valets and hair-dressers; taking to the comb and brush congenially as to the castanets, and flourishing them apparently with almost equal satisfaction. There is, too, a smooth tact about them in this employment, with a marvelous, noiseless, gliding briskness, not ungraceful in its way, singularly pleasing to behold, and still more so to be the manipulated subject of. And above all is the great gift of good-humor…a certain easy cheerfulness, harmonious in every glance and gesture; as though God had set the whole negro to some pleasant tune.”2 Babo feeds into the perception, but if Delano listened carefully, he would hear a more defiant tune. Amazed at Babo's “steady good conduct,” Delano makes an offer in jest: “I would like to have your man myself—what will you take for him?” Babo objects that he would not part from “master” for any amount of money. This is an early sign that things are not what they seem. Babo plays the role of loyal servant to evoke the common perception of the paternal master-slave relationship. Yet, on the other hand, behind Babo's mask is the leader of the revolt who has forced Cereno to submit even though he can easily cry out to Delano.

Babo searches for a sharp razor to shave Cereno. Babo repeatedly strokes the razor “on the firm, smooth, oily skin of his open palm.” He places the razor above Cereno's face as if to begin, but then suspends it inches from his throat while Babo's free hand dabbles “among the bubbling suds on the Spaniard's lank neck.” Cereno shivers from fear at the sight of the sharp steel held at his throat. At this moment, Delano ponders this erratic behavior between master and servant. In Babo, he sees “a headsman,” and in Cereno, a subject “at the block.” The scene would have been familiar to northern and southern antebellum society: a black barber holding the razor to his white customer's neck. Delano acknowledges the “elephant” that white society refused to acknowledge—the unspeakable, though momentary, power that a razor-wielding black man held over his totally defenseless white customer. Cereno represents the white patrons who black barbers shave daily, while Delano represents the larger white public that views blacks as especially suited for service work. At this moment, however, Delano pictures a reversed role of power relations that are and are not what they appear. Eric Sundquist describes this scene as the figure of tautology where Babo slides into mastery and Cereno slides into dependency.3 For Christopher Freeburg, Babo performs a “ruse of objectification” that reveals the failures of “absolute mastership.”4 This paradox creates a visual narrative for antebellum white society that calls into question the ideology of inferiority inherent in black service work in private and public spheres.

The revolutionary seed was never far from the surface. “Now, master,” exclaims Babo as Cereno squirms in the chair, “You must not shake so, master. See, Don Amasa, master always shakes when I shave him. And yet master knows I never yet have drawn blood, though it's true, if master will shake so, I may some of these times.” That time is not far off. Suddenly, Babo's razor draws blood from Cereno's throat. While the blood stains the white creamy lather under his throat, Babo, facing Benito with his back to Delano, pulls back the razor while still holding it up as the blood trickles down. Babo, “with a sort of half humorous sorrow,” declares, “See, master—you shook so—here's Babo's first blood.”

Benito Cereno reminded all slaveholders and the larger white antebellum public who relied on slave and free black service workers that, even if they had not drawn blood as Babo had, anger might be quietly brewing behind the “good-humored,” “cheerful” slaves who cared for them. Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a Massachusetts minister and abolitionist, publically expressed these very concerns. “I have wondered in times past,” he noted in an address to the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1858, “when I have been so weak-minded as to submit my chin to the razor of a coloured brother, as sharp steel grazed my skin, at the patience of the negro shaving the white man for many years, yet [keeping] the razor outside of the throat. We forget the heroes of San Domingo.”5 Even as Higginson advocated abolition, he recognized the simmering seeds of resentment and frustration. Melville's shaving scene captures the ambiguities between the appearance and reality of Babo's position in relation to Cereno and Delano, as well as other black barbers’ positions vis-à-vis their white patrons and a larger white public.

While black barbers did not draw much blood from their customers, barbering between 1830 and 1865 opened much needed physical and economic mobility for both slaves and free blacks. Black barbers negotiated their position as captive capitalists in a slave society where their lives and livelihoods depended on shaving white men. Barbering symbolized both the possibilities and limits of freedom for African Americans in the antebellum period. Economically prosperous yet socially and politically marginalized, black barbers endured the stigma of servility to achieve a measure of independence. They capitalized on white patrons who imagined, and paid for, apparent servitude. But this perceived servitude was service in the minds of black barbers. The line between servitude and service informed the meanings of barbering as a trade and a business in antebellum America.

All black barbers were not owners, and all were not free. The antebellum black barber shop was a place where slaves and free blacks, capital and labor lived and worked together. As such, they all came to the barber shop for different reasons, but they all used their barbering skills and the shop as a route toward skilled work and freedom from slavery and wage dependency. African Americans worked as barbers and in other personal service occupations to gain more control of their time and livelihood. For slaves, becoming a barber was both a step away from the close supervision of the master and a step toward freedom. Barbers’ entrepreneurial pursuits helped them acquire a modicum of wealth and attain social standing in black communities. They were actively involved in black politics and community life. In fact, because they worked among whites and lived among blacks, they were key conduits in abolitionist networks.

Despite barbers’ work in assisting fugitive slaves and participating in local and national black political movements, black middle-class reformers could not overlook how barbers made their living. They encouraged black men to leave the service industry behind for more manly and respectable occupations such as industrial jobs. They viewed barbering for whites as signs of unmanly service work unfit for a free people in a free society. Black men's ideas of independence, manhood, and freedom were played out in their discourses on the respectability of barbering as a means of labor and entrepreneurship.

Black Barbers in a Slave Society

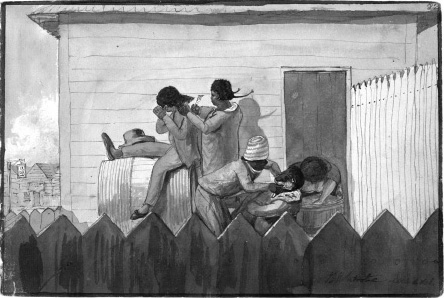

Antebellum slaves groomed men of the slave community and the master class. As early as the eighteenth century, slaves—untrained or trained barbers and hairdressers—spent Sunday morning grooming the hair and faces of fellow slaves in preparation for Sunday worship services. Worship services and holiday celebrations were about the only occasions when slaves could gather in leisure, and many slave owners monitored these activities as best they could. Therefore, the porch or yard outside the slave quarters served as their “barber shop” and “beauty shop.” In March 1797, Benjamin Henry Latrobe, an architect who had emigrated from England and settled in Virginia the previous year, painted a scene he observed during his travels through Virginia of slaves tending to each other's hair on Sunday morning. Latrobe noted in his sketch book that once these men had completed the styling and shaving, they ended the “scene by mutually shaving and dressing each other.”6 It is possible that some slaves used their Saturday afternoon leisure time for grooming, along with other personal chores, before social gatherings later that evening; however, Sunday afforded much more time.7

These Sunday morning grooming rituals continued into the nineteenth century. In the early 1830s, Joseph Ingrham, a white New Englander traveling near Natchez, Mississippi, described slaves preparing for worship services as an example of a properly managed plantation. “No scene can be livelier or more interesting to a Northerner,” he noted, “than that which the negro quarters of a well regulated plantation present, on a Sabbath morning, just before church hour. In every cabin the men are shaving and dressing—the women, arrayed in their gay muslins, are arranging their frizzy hair, in which they take no little pride.”8 Where Ingrham witnessed signs of contentment, former slave James Williams of Alabama remembered discontent. “The only time the slaves had to comb their hair was on Sunday,” he lamented. “They would comb and roll each other's hair and the men would cut each other's hair. That's all the time they got.”9 This time was not enough, especially considering the grueling work regimes they endured throughout the week. In this Sunday morning practice slaves groomed themselves as an act of control over their bodies and appearances.

Figure 1. Preparations for the Enjoyment of a Fine Sunday Evening. 1797. Work on paper by Benjamin Henry Latrobe. Latrobe Sketchbooks/Museum Department. Image ID 1960.108.1.2.36, Courtesy of the Maryland Historical Society.

Unfortunately, slave grooming practices were not limited to looking good for the Lord. Slave traders forced captives to be “dressed” for the slave auction to appear attractive for a master of a different sort. Former slave William Anderson recounted in his slave narrative the dressing process he witnessed while in a slave pen in Natchez, Mississippi. “The slaves are made to shave and wash in greasy pot liquor,” he recalled, “to make them look sleek and nice; their heads must be combed, and their best clothes put on.”10 John Brown went through a similar process in a New Orleans pen when mulatto Bob Freeman “roused” the slaves in the morning to prepare for the day's auction.11 Traders called on slaves who were not captives of the pen to groom the other slaves for sale. William Wells Brown first tried his hand at barbering when he was ordered to prepare “old slaves” in a New Orleans slave pen. Brown's owner ordered him to “shave off the old men's whiskers, and to pluck out the grey hairs where they were not too numerous; where they were, [I] coloured them with a preparation of blacking with a blacking brush. After having gone through the blacking process, they looked ten or fifteen years younger.”12 Considering Brown was not “well skilled in the use of scissors and razor,” he believed he “performed the office of the barber tolerably.” Brown blurred the line between the “tolerable” aspects of the barber's office. He referred to his inexperience as a barber and the decent job he performed with the scissors and razor. Yet the wrenching task of making slaves more attractive to be sold raised the stakes of what was “tolerable” for the barber's office, insofar as Brown made those on the auction block look younger and hence more valuable.13

Most slaves, however, picked up a razor in the service of their master's personal grooming and plantation economies. Barbers filled the ranks of skilled slaves who worked in various capacities and places throughout the South in the antebellum period. Enslaved men, as body servants to their owners, were charged with daily personal duties that included shaving. In a Works Progress Administration (WPA) interview in 1938, Bill Reese recounted his father's entry into barbering while a slave in Georgia. “As soon as he was big enough to be trained for a trade,” Reese stated, “his master arranged for him to learn how to be a barber. High-class white folks liked to have their own barbers then and they wanted ’em well trained, and professional men like pa's owner liked to have at least one slave that could do what they called valet service now.” As an apprentice, he learned all of the duties of operating a barber shop, such as “blacking” shoes, attending to customers, stropping razors, shaving, and cutting hair.14

Slaves who performed service work around the plantation did not generate income, but they were considered investment assets that could be hired out. Enslaved barbers who worked as personal servants could be shifted around in their masters’ business plans to cover losses or generate new income. To leverage their skilled slaves and recover from slow economies, some owners moved these slaves to the field, but most hired them out for the extra money.15 They either identified a shop and directly hired out their slaves, or allowed them to roam the city streets, find their own work, and hire themselves out. Enslaved boys, between ten and fifteen years old, worked as apprentices to free black barbers—and in some cases lived with them—for five to seven years, or until they reached the age of eighteen or twenty-one.16 Isaac Throgmorton became a barber when he moved to Louisville, Kentucky. His owner was a peddler, and according to Throgmorton, “his servants were always out.” “He put me at a trade with a free man and I lived with free people.” Throgmorton served a seven-year apprenticeship before he “kept shop” for himself for two years, then “one year steamboating up the river.”17 Master and employer (or slave and employer in cases of self-hire) negotiated the terms of the contract, which included wages and length of service. On average, enslaved barbers in a city such as Natchez received $12 per month, and in New Orleans $20 per month.18 After surrendering a portion to their masters, enslaved barbers saved or spent the remainder of their earnings.

Antebellum enslaved barbers were hired out to free blacks because the latter dominated the field. Barbering offered free blacks, in the South and North, employment in a high-demand industry with the potential to achieve economic independence. Free black barbers, journeymen and owners, in the antebellum southern economy worked either in downtown shops or on steamboats. Many seized the opportunity to become entrepreneurs in an industry void of white competition, with minimal startup costs and significant profit potential. Barbering lacked the kind of industry-specific labor organization that defined certain cities. Many slaves worked on the waterfront in port cities, like Charleston, South Carolina, for example. Barbering, though, was portable even if smaller towns and cities could accommodate fewer barbers than more populated areas. Free black workers in skilled trades faced the same labor restrictions as skilled slaves in urban areas. Blacks encountered strong opposition from white workers in skilled trades such as blacksmithing, carpentering, and caulking.19 Barbering as a job classification—always ambiguous and politically and racially defined—regularly shifted among personal service, semi-skilled, and skilled depending on one's position in the trade. These categories, however, were not mutually exclusive. Whether or not white workers wanted to admit it, barbering required skill. The average person could not shave with a straight razor without drawing blood. Barbering was one of the leading occupations for black men in the urban North, even though they did not have the same monopoly of the trade as their southern counterparts.

As white indentured servants moved steadily out of barbering after the American Revolution, the prevalence of black barbers reinforced the belief that barbering was unsuitable work for citizens.20 But, if citizens shunned this service work, their identities were nevertheless groomed through its consumption. Having their wigs touched up was a moment when their gentility could be bolstered and they could remind themselves that, regardless of their station in life, they were not serving others. Only the fictions of republicanism could make this logic work: the financial remuneration from barbering made black barbers economically independent, yet the ties between citizenship and whiteness persisted. The eighteenth-century ideas linking barbering and blackness persisted into the nineteenth century and became stronger as slavery expanded westward.

The abundance of southern black men tending to white patrons informed opinions about barbering, service, and skill. In the nineteenth century, barbering and other service-related occupations had a stigma of servility in the South. As historian Ira Berlin argues, “The servile nature of the job drove away white competitors, while it encouraged the patronage of white customers who felt they should be served by blacks.”21 Where African Americans were relegated to certain occupations (personal and domestic service and manual labor), the occupation itself became racialized. As late as the early twentieth century, one historian observed, “A distinguished gentleman of Richmond, who in 1912 was eighty-four years of age, asserts that in all his life he never had a barber who was not colored to cut his hair or shave him.”22 Such long-standing southern traditions reinforced perceptions that blacks were made for barbering. The intimate service that barbers provided for their customers informed the social value and skill level whites attached to the trade. White barbers were rare fixtures in most southern cities until the late nineteenth century, leaving the trade almost exclusively to blacks.23

While the presence of black barbers was a familiar scene, white foreign travelers offered more detailed observations on the racial make-up of southern barber shops. When William Russell traveled throughout the Union and Confederacy from 1861 to 1862 as a war correspondent for the Times of London, he “descended into the barber's shop” in the Willard Hotel in Washington, D.C., one day to discover “all the operators [were] men of colour, mostly mulattoes, or yellow lads, good looking, dressed in clean white jackets and aprons, smart, quick, and attentive.” He suggested that barbering appeared to be “the birthright of the free negro and coloured man” because they seemed skilled at their work.24

Russell's observation of the prevalence of mixed-race barbers points to the demographics of free black barbers. Barbers of mixed-race parentage stood out among the ranks of free black barbers because their white fathers were more likely to manumit them and help them establish themselves. In the early nineteenth century, skilled artisans and house servants were more likely to be manumitted. Richmond barber John Powell recalled that his antebellum boss, William Lyons, groomed his master, who was also his father. According to Powell, Lyons “got paid well for his work, soon was able to buy his freedom. And his father set him up in business.”25 The inconsistencies of racial classifications make it difficult to get an accurate count of the total numbers of dark- and light-skinned black barbers. For example, the 1850 U.S. census listed Reuben West, one of the leading black barbers in Richmond, Virginia, as a mulatto. However, the 1860 census listed West as black.26 West was light skinned and one of the wealthiest barbers and businessmen in the state. The leading black barbers in the nineteenth century were of mixed race.

Barbers counted themselves as tradesmen and were part of the craft hierarchy that moved from apprentice, to journeyman, to master barber, to shop owner. Formerly enslaved, William Johnson learned barbering from his brother-in-law, James Miller, the “most widely patronized barber in Natchez, Mississippi.” Johnson saved enough money to acquire a barber shop in 1828 in Port Gibson, Mississippi, fifty miles north of Natchez. He took in $1,094 in twenty-two months at this location by “Hair Cutting and Shaving alone.” On October 14, 1830, Miller sold the unexpired portion of the lease on his Main Street shop to twenty-one-year-old Johnson for $300. In 1833, Johnson made a down payment of $1,375, half the purchase price, to acquire the building property and retired the note in less than two years. He charged 24 cents for haircuts and 12.5 cents per shave ($1.50 per month). In 1834, he erected a bathhouse at a cost of $170, charging 50 cents for a hot or cold bath. Most of his customers paid cash, but many secured credit.27 Johnson made substantial improvements to his Main Street shop and expanded to new locations. The Main Street shop eventually contained six chairs, “two washstands, a coatrack and a hatrack [sic], a table and a desk, and two sofas, while the walls were ornamented by four mirrors and more than thirty framed pictures, including several horse-racing scenes.” In the late 1830s and 1840s, he opened two small one-man barber shops: the “Natchez-under-the-Hill” shop and one located in the Tremont House, a small hotel around the corner from his shop on Main Street. Slaves or free black employees operated both shops. Johnson also traveled to customers’ homes and businesses to perform barbering work. During his first three years in business, Johnson's expenses and income averaged $1,500 and $2,500, respectively.28

Johnson's successes may not be representative, but journeymen could move into the entrepreneurial class rather fluidly in barbering. When a steamboat captain cheated William Wells Brown out of his pay in the fall of 1835, Brown was forced to seek employment in nearby towns. While looking for work in Monroe, Michigan, between Detroit and Toledo along Lake Erie, he “passed the door of the only barber in the town, whose shop appeared to be filled with persons waiting to be shaved.” Since there was only one barber in the shop, Brown figured he would draw on his barbering experience from shaving slaves at slave auctions and shaving white men on the steamer to earn money for the winter. The barber turned down Brown's persistent requests to work, even at low pay. Finally, a frustrated Brown threatened to open a nearby barber shop to compete with the barber. According to Brown, the barber showed no concern; after all, if Brown was looking for work, where would he find the money to open a shop? Moreover, as a newcomer to a small town, Brown would have a difficult time attracting customers. Brown reported that one day, as he was leaving the shop, “one of the men, who were waiting to be shaved,” offered to help him set up a shop across the street and “promised to give me his influence.” If this indeed was the only barber shop in town, with one barber, then perhaps this customer had waited too long, too often. Brown accepted the customer's offer to open his own shop.29

Brown became an entrepreneur by chance, but his move reflects the low barriers to entry to becoming a shop owner. He outfitted his small shop modestly, but he created an image—a “brand” in business terms—that was worth much more. “I…purchased an old table, two chairs, got a pole with a red stripe painted around it,” he recalled, “and the next day opened.” Brown did not mention it, but he, of course, would have needed such instruments as scissors, razors, towels, and shaving mugs—all inexpensive items. His most expensive piece of equipment was a sign over the door that read “Fashionable Hair-dresser from New York, Emperor of the West.” He spread word that his competitor's shop “did not keep clean towels, that his razors were dull, and, above all, he never had been to New York to see the fashions.” Brown failed to mention that he had not been to New York, either, and led his customers to believe that he was bringing big-city style to Monroe. According to Brown, he commanded the “entire business of the town,” mostly white residents, in a matter of a few weeks.30

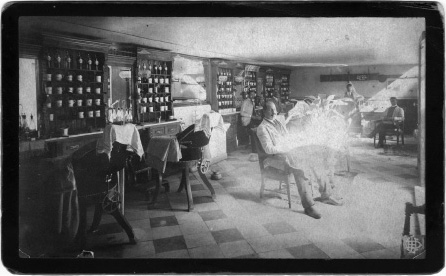

The structure of Brown's small-town barber shop was typical even among big-city shops, but the elite owners started with more elaborate equipment and extensive services. There were no fundamental differences in organization and location between northern and southern shops. Most black barbers opened their shops in or near commercial districts where businessmen and politicians moved about. They leased space in various office buildings and in leading hotels to attract middle-class visitors.31 Lewis Woodson operated his shops in several Pittsburgh hotels, including the Anderson, the St. Charles, and the Monongahela House. Many residents considered the Monongahela House the finest hotel in the city and the region. Woodson joined John Vashon, John Peck, and Lemuel Googins as the leading black barber shop owners in the city.32 Vashon opened his shop in 1833—which included a sign that read “Shaving, Hair Dressing, and Fancy Establishment”—inside a building on 59 Third Street, next door to his home. Located downtown, the shop served as a center of information among white male residents and travelers. The average barber shop was intimately structured to foster familiarity and trust among customers. Regular patrons could count on seeing their personal shaving mug on a rack. Barbers were assured of regular visits, and patrons grew accustomed to the personal attention.

Figure 2. Barber shop with shaving mug racks, circa 1890. The shaving mug racks were standard in most barber shops in the 1800s. Meta Warrick Fuller Photograph Collection. Courtesy of the Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

Barbers structured their shops to complement the business strategies of financiers who looked to accommodate their elite consumers’ desires in luxury hotels. These hotels employed what historian Molly Berger terms “technological luxury” to appeal to elite gentility.33 A bathhouse was one such luxury that the leading barbers incorporated in their service offerings. In the early nineteenth century, few Americans bathed because of the scarcity of indoor plumbing. Cities began to install public water and sewage systems based on who could pay. Therefore, the wealthy received benefits of the system faster than the general population. Yet indoor plumbing was still not widespread even among the wealthy.34 The public bath movement has its American origins in the 1840s when health reformers began emphasizing connections between cleanliness and physical fitness. As the well-to-do became more accustomed to bathing, they used personal cleanliness as a mark of superiority over the poor and working class. To be sure, bathhouses were not just for the wealthy. In fact, urban reformers hoped to wash away the “moral depravity” of the poor by convincing them to bathe more. While the most “elegant hotels afforded their guests the pleasures of a bath,” the middle and upper classes could also avoid bathing with the lower classes by going to bathhouses attached to upscale commercial businesses such as barber shops.35

Barbers capitalized on the new technology and air of exclusiveness bathhouses brought to the public sphere. In 1833, Vashon opened the first public bathhouse west of the Alleghenies, on Third Street between Market and Ferry Streets in Pittsburgh.36 Men bathed on the lower level, while the upper level was reserved for women. To maintain security and privacy for the upper level, the entrances to each level were separate.37 After several years, he made major renovations and advertised its reopening:

CITY BATHS

The subscriber respectfully informs citizens of Pittsburgh, and strangers visiting here, that his Warm, Cold, Shower Baths for Ladies and Gentlemen…having undergone thorough repairs, and being brilliantly illuminated with Gas Lights, are now open for the season, every day, (Sunday excepted), from 6 o'clock, A.M. to 11: o'clock, P.M. The subscriber feels grateful for the patronage so liberally bestowed upon him by the public and will spare no pains to merit a continuance of its favors.38

Vashon's barber shop and city bath were business and political clubs for the city's white leadership.39 In 1836, a Nashville barber, “Doctor Jack,” advertised his baths as a place where patrons could enjoy “the falling spray, the lucid coolness [of] the flood.” The bathhouse had separate facilities for women, staffed with female attendants.40 William Johnson noticed that public baths were opening in various cities, so in 1834 he decided to open one of his own. While most of the bathing customers were men, who were probably also his barber shop patrons, he noted in 1840 that a “French lady” took a bath. The bathhouse was not profitable, but it offered patrons “relief from the heat and dust of the unpaved streets.”41 William Johnson's enormous success as a barber, like that of other black barbers, depended on the breadth of services he offered his patrons. St. Louis barbers Louis Clamorgan and Mr. Iredell highlighted the luxurious services of their shops. An 1845 advertisement noted their “Splendid Hair Cutting and Shaving Saloon” and a bathhouse with tubs of “the finest Italian marble, the rooms large, airy and elegantly furnished.”42 Barbers appealed to the sensibilities of their white clients to provide complete bodily grooming. These kinds of business decisions at once imagined barber shops as spaces to enjoy the serene landscape of bodily care and as places that provided multiple revenue streams for the owner.

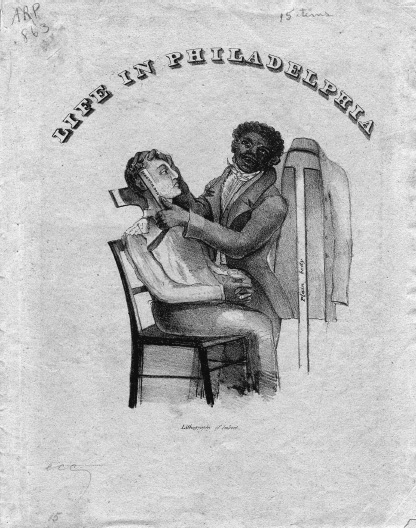

Grooming the white public propelled many black barbers into the black middle class and elite, measured through wealth and status. Before the Civil War, black professionals, entrepreneurs, carpenters, tailors, waiters and cooks in ritzy hotels, and barbers made up the economic elite. Philadelphia's black elite intrigued white artists David Claypool Johnson, William Thackera, and Edward Clay enough that they created graphic racial caricatures of black society in public and private life. In the late 1820s, Clay produced a vicious series of colored prints entitled Life in Philadelphia. His lithograph series painted the black middle class as pretentious, uneducated, and on the brink of turning the city (with the help of white abolitionists) into an amalgamated society with interracial marriage and biracial children.43 These and other prints portrayed whites’ anxieties about black economic mobility at the time.

Anthony Imbert drew a wrapper illustration for the Life in Philadelphia series that depicted a well-dressed black barber prepared to shave a white customer. The barber, dressed in a fancy coat with an ornate collar, stands above his customer, who is dressed rather plainly, while his coat rests on a hanger labeled “plain body.” The barber holds a razor, with “Magnum Don,” which means “great gentleman,” on the blade, thus making barbering the source of the class portrayal.44 Imbert cast the barber in a pretentious image, or as a dandy, by dressing him in a fancy coat instead of his barber's smock or apron.45 Most intriguing about this illustration are the particulars of shaving-time. The barber looks away from the customer, presumably at those looking at him or the illustration, while he holds the razor on the side of the customer's lathered face. The customer looks rather relaxed, with a content face and folded hands.

Figure 3. Anthony Imbert, wrapper illustration, Life in Philadelphia (1828), Bd 912 Im1 83. Courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Barbers composed a large segment of the southern black elite, in some cases because of their wealth, but in most cases because they had formed relationships with their prominent white patrons. In 1858, Cyprian Clamorgan published his survey of the St. Louis black elite in The Colored Aristocracy of St. Louis. For Clamorgan, the “colored aristocracy” referred to African Americans “who move in a certain circle; who, by means of wealth, education, or natural ability, form a peculiar class—the elite of the colored race.” He particularly highlighted the large number of barbers in this group. “It will doubtless be observed by the reader,” he noted, “that a majority of our colored aristocracy belong to the tonsorial profession; a mulatto takes to razor and soap as naturally as a young duck to a pool of water, or a strapped Frenchman to dancing; they certainly make the best barbers in the world, and were doubtless intended by nature for the art. In its exercise, they take white men by the nose without giving offense, and without causing an effusion of blood.”46 There was nothing “natural” about the predominance of mixed-race barbers in St. Louis or any other city. Barbers who catered to the white elite were indeed wealthy, but it is no surprise Clamorgan, a mixed-race barber himself, profiled a large number of barbers in his survey of the black elite. Nineteen of the thirty-two men profiled were barber shop owners or journeymen.47 Clamorgan's book served as an advertisement of black barbers’ capabilities as businessmen, but more particularly let customers know that they would not let the razor slip.

Not all black barbers were among the elite. In fact, a look at the shop level reveals a complicated interplay between owners and employees, slave and free. A precarious mix of free and enslaved black barbers attended to these bathhouses, opened and closed the shop, stropped the razors, and shaved customers. William Mundin, free born and of mixed race, served an apprenticeship with Reuben West alongside his slave apprentice in his Richmond barber shop.48 Johnson had two free blacks working in his Natchez barber shops, far less than the five or six slaves he employed. He employed free black apprentices Wellington West and Washington Sterns, both of mixed race, to work intermittently in his shops. Johnson acted as employer and guardian to his slave and free apprentices. West and Sterns received an average of $25 per month, double the wages of slave apprentices. Occasionally, Johnson also gave his free apprentices food and clothing.49

Like most workers, free black apprentices wanted to improve their wages and well-being and took advantages of opportunities regardless of the race or goodwill of their employer. Free black barbers looking for more mobility, beyond the stationary downtown shop or traveling to customers’ homes, found it on steamboats. Many slaves hiring their time as barbers, such as Isaac Throgmorton of New Orleans and Frank Parrish of Nashville, found work aboard steamboats, but according to historian Thomas Buchanan, free blacks made up most of the black workforce on the western rivers. Buchanan further suggests that only the larger boats commonly provided barbering services for their passengers. Barbers rented small shops at one end of the cabin, where they groomed passengers for fees and tips, unlike other steamboat workers, such as stewards, who were on the clerk's payroll. Steamboat barbering gave free black journeymen an opportunity to travel while maintaining their economic autonomy.50

When journeymen took to the river, they occasionally left inland shop owners in a bind. James Thomas understood the allure of barbering on steamboats because he had once been a steamboat barber for a year. As a shop owner in Nashville, he recalled, “In the antebellum times, when the large number of steamboats needed barbers, the shop keepers had hard work getting men to stick.”51 Farther south in Natchez, William Johnson agreed. On January 15, 1848, he recorded in his diary, “Bill Nix Commenced to run on the Steam Boat Princess as Barber.” Over two years later, he noted, “My force at present in the shop is myself, Edd [sic] and Jim, for Jeff has left and taken the Shop on the S.B. Natchez and he is starting now for New Orleans.”52 In additional entries, Johnson noted that his free black barbers had left to work on a steamboat. In his diary, Johnson did not openly express disappointment or annoyance at his barbers for taking off, suggesting that free black journeymen had some level of independence and flexibility in their work schedules.

While free black employees might skip out on the shop for better opportunities, enslaved apprentices had to answer to an employer and a master. Although white masters left direct supervision of their slaves to black employers, masters, as absentee owners, maintained their power and paternalism in the master-slave relationship. Between 1835 and 1851, William Johnson hired about five apprentices. William Winston, John, Bill Nix, Steven, and Charles were slave apprentices in his shop for a number of years. On July 5, 1836, Johnson wrote that twelve-year-old “little William Winston came to stay with me to Le[a]rn the Barber trade.” Winston's owner, Fountain Winston, provided in his will that Winston should be emancipated when he reached twenty-one years of age.53 Johnson's slave apprentices regularly worked in his principal shop unsupervised. He allowed Charles to operate his “Natchez-under-the-Hill” shop, and Bill Nix to operate the one near Rodney, Mississippi. Major Young, the owner of one of Johnson's apprentices, informed Johnson that he wanted to help his slave set up a shop of his own. “I saw maj young this evening,” Johnson wrote in his diary, “and he told me that he wanted to do something for charles and that he wished to give him a start in a shop to hisself. I told him very well, and he spoke of setting him free. And that if he did he thought it would be attended with some difficulty in regard to his coming back here again.”54 Young showed less concern with Charles becoming free than with his being forced to leave Mississippi. Young's benevolent aspirations guided his paternalistic guardianship for Charles's future. He entered the life of nominal freedom that many barbers knew all too well.

White masters, black employers, and the law determined the degrees of freedom slave barbers could enjoy. Matters of degree, however, are luxuries of distant historical analysis. Slave barbers in southern cities were “master-less” slaves, but they were nonetheless slaves. Ebenezer Allison “served his time in the barber's shop” in Richmond, Virginia. He was hired out from John Tilgham Foster, who, according to Ebenezer, was a kind master. His kindness, though, fell short of freedom, which for Ebenezer had no middle ground. “I had no right to leave him in the world,” Foster reasoned, “but I loved freedom better than Slavery.”55 If living among freemen and earning wages was a privilege, having to relinquish a portion of their earnings and being sold to a more controlling owner reminded barbers they were not free. Isaac Throgmorton believed he lived a free life because he worked and lived among free blacks. “Only when he [his master] would send for me to come round,” Throgmorton concluded, he would “let me know that I was not altogether free.”56 The moments when Isaac was called to “come round” were perhaps moments when his owner expected the agreed-on portion of Throgmorton's income. Being summoned and forfeiting a portion of the fruits of his labor represented critical aspects of Isaac's freedom. Barbering offered him the opportunity to live in relative freedom at least for intermittent periods of his life in the city. Quite simply, barbers similarly situated like Throgmorton wanted to be neither slaves on the plantation nor hired-out slaves living relatively free. Even as apprentices to free black barbers, there was no solace in their bondage in a “masterless” labor arrangement.

Free black employers did not just hire enslaved apprentices—some also acquired their own slaves. Free black barbers used their profits to purchase family members still in bondage. Since many southern states in the first half of the nineteenth century required freed slaves to leave the state within twelve months of their manumission, when free black barbers purchased relatives, they were registered as slaves instead of “freed.” Richard C. Hobson, of Richmond, was emancipated in 1841. He used the profits from barbering to purchase his wife and son, but did not manumit them until 1850, when the court allowed them all to remain in Virginia.57 Black barbers were among a contingent of free black slave owners who did not emancipate relatives they purchased because of state removal laws, and purchased slaves to work in their businesses.

Black slave owners purchased slaves for both benevolent and commercial reasons. Directing their skills toward urban consumers, free black entrepreneurs faced a limited labor supply. White workers generally refused to work for free blacks, while free black artisans had other opportunities.58 Thus, black barbers addressed a glaring concern of a small labor supply by tapping the one large supply that existed in the nineteenth century: slave labor. The prosperity of black artisans allowed them to invest in human chattel, train them in the skills of their trade, and further increase the profits of their businesses.59 In most cases, the slaves who worked in black barber shops were more than likely hiring their time. Black slave owners who were barbers owned between one and five slaves. Their slaves either apprenticed in their barber shops, were house servants, or both. Between 1840 and 1860, the six leading black barbers in Richmond owned one or two slaves.60 During the 1850s, Reuben West owned a house servant who he later sold because of her “spirit of insubordination.” James H. Hill, a contemporary of West's, asserted that West “owned two slaves, and that one of them was a mulatto barber” in his four-chair barber shop on Main Street.61

The labor relationships between black owners and enslaved hired-out workers, however, were not as fluid as those between owners and free employees. The master-slave relationship between free black barbers and their enslaved apprentices cannot be compared with the relationship between white masters and slaves. Even though black barbers held limited boundaries around their apprentices, they were still legally bound for a period of time, and they clearly understood they were not free. William Johnson fed and clothed his enslaved apprentices, provided for their education, and allowed them space to enjoy leisure activities with or without his free apprentices. They received passes to attend the theater, the circus, and parties given by local servants.62 But, Johnson monitored their leisure activities. He outspokenly disapproved of their “ungentlemanly” behavior at every turn.

Johnson's experience reveals that the tension between black masters and black apprentices was less about labor than about leisure. In his diary, Johnson recorded his disappointments in some of his apprentices’ behavior. Beyond the daily record, he disciplined them with beatings when they were too leisurely, quarreled, or engaged in coarse public behavior. On December 17, 1835, Johnson wrote in his diary, “William & John & Bill Nix staid out untill ½ 10 O'clock at night. When the[y] came they knocked so Loud at the Door and made so much noise that I came Out with my stick and pounded both of the Williams and J. John ran Out of the Yard and was caught by the Patroll, Mr. McConnell and Reynolds. I made Mr. McConnell give him 12 or 15 Lashes with his Jacket off.” When John ran out of Johnson's yard, he ran into the public sphere of the institution of slavery. Johnson drew on the services of the state—making the patrol whip John—to signal that he could manage his slaves. On another occasion five years later, John and Winston went hunting by the lake, and Johnson “wrode up thare and caught both of them and gave them both a flogging and took away their guns—I threw away winston's as far as I could in the Mississippi [River].”63 To be sure, most slaves did not carry guns. The mere sight would have sent the entire planter class into immediate hysteria, which explains why Johnson did not wait for them to return. But again, Johnson was likely more concerned about what white citizens of Natchez would think about allowing his slaves to have access to weapons of rebellion, even if used only for leisure.64 If we read Johnson's diary against the grain—read the experiences of his barbering apprentices through his words—we get a more complicated narrative of how African American men barbered for freedom.

Johnson suggested in his diary that of all his enslaved apprentices, Steven gave him the most grief. Steven resisted Johnson's rules and control at almost every turn. He drank heavily and ran away often. The tension between Johnson and Steven began seven weeks after Steven entered an apprenticeship with him on January 2, 1836. “I had to Beat Steven this morning,” Johnson recorded on February 23, “for taking the shop key away and was not ready to open the Shop.”65 Steven had the freedom to take the key and open the shop without supervision. Therefore, his infraction was not taking the key, but opening late. Perhaps this was Steven's form of resistance, a kind of work slowdown. If this was an offense that warranted a beating, Johnson wanted to make a point to Steven (and his other apprentices) about what was acceptable behavior. Johnson did not write about Steven opening the shop late again, but there were numerous entries about Steven's drinking activities during his leisure time.

From August 1840 to January 1844, Steven got drunk and ran away so often that Johnson mentioned his actions almost nonchalantly. Less than one month before Johnson began noting Steven's propensity to drink, he released a free black employee because “to be drunk ½ of his time would never suit me nor my customers.”66 Perhaps this made Johnson more attentive to the drinking habits of his other employees. His entries concerning Steven were as follows:

August 10, 1840: “steven was twice whipped for being drunk. He ranaway.”

September 12, 1841: “hired steven out to mr. Gregory to haul wood in the swamp. Apparently he ran away, and stole a watch. Was whipped and sent back to Gregory.”

October 1, 1842: “steven ran off again.”

January 26, 1843: “steven ran away after getting drunk. I will astonish him some of these days if he is not Careful.”

August 14, 1843: “steven ranaway yesterday and was brot home to day by bill nix. I gave him a floging and let him go—no, I mistake, it was today that he ranaway.”

August 24, 1843: “I came very near cetching steven to night. He was in the stable ajoin[in]g mine but he jumped out and ran into the weeds somewhere.”

Steven disappeared so frequently that Johnson had a hard time keeping track. On December 19, 1843, Johnson finally grew tired and frustrated at not being able to control Steven and contemplated selling him. “Steven is drunk to day and is on the town but I herd [sic] of him around at Mr. Brovert butlers and I sent around there and had him brought home and I have him now up in the garret fast and I will sell him if I can get six hundred dollars for him, I was offered 550 to day for him but would not take it. He must go for he will drink.”67 Although Johnson was clearly upset that Steven constantly ran away, he was more upset that Steven drank so often, and did so in public. Four years later, Johnson explicitly cited Steven's love for liquor as the principal reason he sold him. On January 1, 1844, he sold Steven to “the overseer of Young & Cannon” for $600. Johnson “felt hurt” because he “would not have parted with him if he had only have let liquor alone.”68 Johnson tolerated Steven's drinking for so many years because selling him was more complicated than releasing his free black barber.

Johnson's admonishments, then, reflected his concern about how his white customers and other white citizens in Natchez would perceive him based on his employees’ public drunkenness. Steven did not need a drink to run away. Although Johnson characterized Steven's absences by writing “he ranaway,” it is quite possible he did not run away as often as Johnson asserted, but that he simply refused to seek permission for his leisure time. Johnson's business was guided by a paternal, hierarchical relationship. White men wanted their black barbers to be submissive and deferential, and in return, black barbers would receive patronage and protection. Johnson acquiesced to this role and sought to teach his employees the mechanics of barbering and the necessary submissiveness that accompanied it. Steven clearly did not fit this mode. A group of barbers like Steven would transform the deferential model that white men expected.

Yet, Johnson was not entirely deferential himself. In fact, whites in Natchez accorded him a little respect. Johnson owned land and hunted. He was a horseman and marksman. Most strikingly, he gambled at the racehorse track and lent money to the city's white agricultural and business community. Socially, he enjoyed the outdoors; economically, he enjoyed making money. His diary is replete with accounting of loans issued, interest charged, and repayment terms. While it was common for black barbers to pose enough wealth to be lenders, it was uncommon for whites to respect them enough to enter into and honor such loan contracts. Nonetheless, Johnson was excluded from various areas of Natchez society. For example, he could not vote or sit next to white men at public gatherings. As his biographers suggest, “He was a part of the community and yet not a part of it.”69 Most importantly for Johnson, he stayed abreast of anything that could cost him money. Steven's drunkenness could do just that. Johnson's penchant for money is most vivid in two rather mundane diary entries the first week of October 1841. Just five days into October he noted, “Business is remarkable dull for this month.” Four days later he penned a similar statement but added that he “Could not Collect any money from Any One.”70 Johnson paid attention to his money, and did not want his unsupervised slave and free apprentices contributing to “dull weeks.”

Throughout the antebellum period, municipalities explored various regulations to control “unsupervised” slaves with considerable mobility like Steven. The restrictions on black labor, slave or free, tied access to skilled trades with a greater propensity for urban mobility. In 1822, the Savannah city council prohibited any black person from being apprenticed “to the trade of Carpenter, Mason, Bricklayer, Barber or any other Mechanical Art or Mystery.”71 According to Brenda Buchanan, “Mechanical Art and Mystery” referred to a craft leading to perfection of workmanship.72 The ordinance sought to prohibit African Americans from learning skilled trades to decrease the likelihood of job competition, but also to limit slaves’ mobility. Some authorities realized they could not control the rising tide of skilled slaves navigating the city without supervision. In 1856, councilmen in Mobile, Alabama, proposed an ordinance to allow slaves to operate their own barber shops only if their owner paid a $10 annual fee. The proposed ordinance required slaves to receive twenty lashes if they operated barber shops without permission from their owners.73 These ordinances attempted to reconcile the varied expectations of the different stakeholders in the institution of slavery. Slaveholders looked to maximize their income, and hiring out slaves could serve those purposes. Even though local governments could not control this practice, many urban dwellers remained ambivalent about it. In 1859, the New Orleans Picayune complained about the slave hiring-out system: “A species of quasi freedom has been granted by many masters to their slaves. They have been permitted to hire their own time, and with nominal protection of their masters, though with none of the oversight, to engage in business on their own account, to live according to their own fancy, to be idle or industrious…provided only the monthly wages are regularly gained.”74 As long as masters stood to profit from hiring out, city councils proved ineffective in stemming the tide of slaves roaming the city.

Enslaved barbers in the city capitalized on the white networks they developed during the course of their labors. They often entered legal arrangements with third-party white benefactors to prevent being sold to a less lenient master. The benefactor would legally own the slave, but the slave was allowed to live on his or her own or to purchase his or her freedom. This was the case with Frank Parrish, a mixed-race slave in Davidson County, Tennessee. When his master died, Frank, along with other property, was left in the care of his master's widow. Mrs. Parrish allowed Frank to hire out his time in Nashville, where he lived with four free blacks on South Cherry Street. Frank supported himself as a barber on steamboats and eventually opened a barber shop and bathhouse. Despite numerous successful years as a barber, at the age of forty-five Frank was still a slave. Upon the death of Mrs. Parrish, Frank was transferred to her heirs. This time, however, he did not leave his life to chance. To prevent his own sale at an estate liquidation, Frank asked for and received an agreement from his white benefactor, Edwin H. Ewing, to purchase him. No one else bid against Ewing, who, in 1853, allowed Frank to purchase his freedom.75

Frank trained another quasi-independent slave barber in Nashville, James P. Thomas. Thomas, also a mixed-race slave, was born in 1827 to Sally Thomas and Judge John Catron, chief justice of the Tennessee Supreme Court and later a U.S. Supreme Court justice. When Sally's owner died in 1834, she sought financial assistance from a white lawyer, Ephraim Foster, to purchase James's freedom out of fear that he might be sold. Foster lent her $50 to purchase James's freedom, but since he did not leave the state as the law required, he legally remained a slave and Foster remained his owner. Circa 1841, he hired out as an apprentice barber with Frank Parrish. In 1846, he opened a barber shop in his childhood home on the corner of Cherry and Deaderick Streets, where his mother still ran a clothes-cleaning shop. The shop was centrally located near the market square, banks, and the courthouse. His customers included businessman E. S. “Squire” Hall, preacher William G. Brownlow, former governor William Carroll, plantation owner William Giles Harding, and Davidson County lawyer Francis Fogg. James asked his owner to petition for his freedom, which he successfully did.76 By the 1850s, southern attitudes and legal manumission codes had changed, increasingly closing off this avenue of freedom, particularly in the lower South.77

As the changing landscape of antebellum slavery altered the world of slaves, the world of free blacks also underwent dramatic shocks as they confronted state laws that required former slaves to leave the state after gaining their freedom. James Thomas lived several years operating a barber shop relatively free, though legally enslaved. Thomas could have arranged for his freedom before he actually did, but he would have come up against the Tennessee law that required freed blacks to leave the state. He enlisted his white benefactor, who was also a customer at his barber shop, to petition for his freedom and challenge the state law. The state granted Thomas's petition, which made him the first black person in the county to gain both freedom and residency.78 Slave barbers like Thomas, who had established successful barber shops or had family members in the state, wanted to remain in the state after they were freed. Virginia, too, required emancipated slaves to leave the state within twelve months after gaining their freedom. This law prohibited free blacks from acquiring slaves, except slave spouses, parents, or slaves who were inherited. Later, free blacks could acquire any slave except descendants.79 North Carolina denied freed blacks permission to enter the state. Southern legislatures enacted these laws in fear that free blacks might conspire to incite slave revolts or otherwise become indigents to the local economy.

Like Thomas, other black barbers in the lower and upper South petitioned the state legislature to remain in the state after they were freed to maintain business dealings and stay close to family members. In 1829, Natchez barber William Hayden petitioned the Mississippi legislature to maintain his residency after he gained his freedom. The 1822 act required him to leave the state, which he argued would “produce absolute ruin” to his business. He contended that he had “a good reputation, and own[ed] property” and therefore should be exempt from the state law. Similarly in 1837, Harrison Minton petitioned to remain in Virginia because he “[was] a barber and able to sustain” himself; in addition, his friends and family were currently enslaved in the state.80 Petitioners usually referenced their industriousness, business acumen, honesty, and family ties in these appeals. In many ways, white citizens were motivated to keep free black service workers in the state to stabilize the service industry.81 In 1852, Charles H. Reynolds complained to a justice of the peace that Joseph Rollins and the other barbers in his shop resided illegally in Louisiana. Rollins was a free black barber who operated a shop in the basement of the Planters’ Hotel in New Orleans. The Daily Picayune reported, “Yesterday the well known Goins, Parsons, and five other barbers, all f.m.c. [free men of color], who have for years past smoothed the chins and curled the hair of thousands of our citizens, were brought before Recorder Caldwell, on the charge of being in the State in contravention of the law. Several of these men have been so long in this city, and have for many years kept such famous barbershops, that their arrest [resulted in] quite an excitement.”82 There is no evidence to suggest they were prosecuted.

If a barber's reputation could prove beneficial, his income could further his pursuit of freedom. On November 22, 1833, Joseph Hostler, a barber in Fayetteville, North Carolina, petitioned the state legislature that his late owner, David Smith, allowed him to purchase his freedom. Hostler reported that he paid his owner $96 per year from his earnings while he hired out his time over four years. In total, he paid his owner and his owner's estate $500.83 The legislature granted Hostler his freedom. Slave owners, however, were notorious for reneging on verbal agreements. That Hostler had to petition at all suggests Smith's estate would not honor the purchase agreement. In the 1850s, Bird Williams allowed his slave James Maguire of Louisiana to hire out as a barber and hairdresser. Maguire received $20 per month, which allowed him to purchase his freedom for $850. After the purchase price was paid, but before he was legally manumitted, Williams died. With no record of the transaction, the firm Harral & Gill acquired Maguire and Williams's other property. Maguire lived with Mr. Harral and served as his personal barber. Mrs. Harral also had Maguire dress her hair regularly, but she preferred he perform his barbering duties in her “bed chamber” after Mr. Harral left for work. When Maguire refused directives, she threatened to “sell him onto a cotton plantation.” He did not wait to see if she was bluffing. He fled.84 Maguire was clearly concerned about being sold onto a plantation, but he was also afraid the appearances of grooming his mistress in her bedroom would lead to his death, which was not the kind of freedom he had in mind.

Self-hired enslaved barbers escaped if their relatively benign experience was altered through sale or the whims of their masters’ relatives. Hiring out allowed enslaved barbers to live and work in cities among freemen and away from the master's gaze, which gave them the resources and the space to escape at will. Lewis Francis hired his time as a barber in Abingdon, Maryland. Each month he relinquished $8 from his earnings to his mistress, Mrs. Delinas. Yet she did not believe she was reaping enough from his labor, so she threatened to sell him. Francis did not take this threat lightly and escaped to Philadelphia.85 Another slave, Richard Eden, hired out his time as a barber in Wilmington, North Carolina. He paid his mistress, widower Mary Loren, $12.50 per month and paid an additional twenty-five cents per month as a head tax to the state. Eden became quite vulnerable, though, when he married a free black woman, an “offense” for which he could have gotten thirty-nine lashes. Afraid he might be sold or that his mistress might renege on the purchase agreement, he and another slave talked of finding the Underground Railroad and made arrangements with the captain of a schooner headed for Philadelphia to stow away. The Philadelphia Vigilance Committee assisted them in getting to Canada, where Eden planned to open a barber shop.86

In many cases, enslaved barbers had known life beyond the direct control of their owners, and they seized every opportunity to realize complete freedom. Isaac Throgmorton revealed that he ran away because he had lived virtually free and had no intention of living otherwise. He stated in an interview:

I will tell you the reason why I ran away. I had one or two reasons. In the first place, as I had been raised a barber and among freemen, it always seemed to me that I was free; but when I was turned over to another man, who kept close round, I saw I was not a freeman; that all the privileges were taken from me, that I had when I was working with freemen. Then, when I was moved from Kentucky to Louisiana, I saw so many cruelties that it sickened my heart, and notwithstanding I was treated well, there was no comfort for me. Then, secondly, although my master treated me well enough, when he got married, his wife and all her kin considered that I had been treated to[o] well, and I knew directly that his head was laid low I would be done forever. I came here in 1853. I had no particular trouble in getting away. This man just wanted me to shave him and travel round with him…. Well, he came up to Kentucky to spend his summers, and he brought me there, and I saw it was a good chance.87

There were a small number of barber shops in most cities, but some white travelers preferred the convenience of having a personal barber to waiting in a shop. To meet these needs, enslaved barbers such as Isaac regularly accompanied their masters or white patrons in their travels to tend to their grooming needs. These travels presented them with numerous opportunities to escape. As a barber, Throgmorton was accustomed to the “privileges” of living with freemen, which proved to be an important vehicle in escaping white surveillance and eventually slavery altogether. For him, this lack of surveillance partly defined his level of freedom.88 Throgmorton's journey to Louisiana proved to be his impetus and springboard to freedom. He disguised himself as a fisherman to escape, and ultimately made it to Canada.

While Throgmorton's southern travels as a barber opened space for him to escape slavery, northern black barbers who traveled south, particularly on steamboats, ran the risk of being accused of being runaways. Barber George Stewart could attest to the experiences of free black barbers who were under constant threat of being labeled fugitives, kidnapped, and sold into slavery. In the spring of 1837, while traveling on the Mississippi River, he was accused of being a fugitive slave and arrested in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. After nearly a year, William Huston, a “Licensed Intelligence” officer in New York City, submitted an affidavit confirming that Stewart was born in New York “of free parents.” It is unknown if Huston was a former customer of Stewart's or if one of his customers enlisted Huston's help on Stewart's behalf, but this detail probably mattered little to Stewart.89 Nineteenth-century law operated under the assumption that if accused, a black person was a fugitive until proven free. The testimony or legal assistance of whites was often critical in such cases.90 Therefore, free black barbers cultivated relationships with their patrons, not just because it made good business sense, but also for their own protection. Even the most prominent barbers, butchers, caterers, and carpenters understood the importance of maintaining cordial relations with their white customers.

Huston vouched for Stewart, but there were scores of fugitive barbers who had to pass as free. They targeted areas with free black populations in the upper South and the North to achieve anonymity and obtain assistance from relatives and sympathizers. Since there were fewer free persons of color in the lower South, fugitives had less space to be anonymous. In the upper South, skilled and literate slaves had a good chance of posing as self-hired slaves or free blacks. Like other skilled and literate fugitive slaves, barbers also employed the method of passing as free by donning fanciful clothing and forging freedom papers.91 It was a bold move indeed for fugitive slaves to escape slavery and earn a living shaving white men. But blending into free black barbering communities under the auspices of anonymity meant negotiating both the urban slave economy and the unequal relationships with white patrons. The presence of self-hired slaves allowed fugitives to seek apprenticeships with free blacks, and the profession of barbering was no exception. Whether posing as a slave hiring his own time or as a free person of color, what did it mean to pass as free by passing as a barber? Runaway mulatto slaves attempted to pass as white to lessen the chances of being challenged. Literate runaways forged freedom papers to pass as free persons of color because it was illegal in most states to teach slaves to read or write. Although most black shop owners were mixed race, to pass as a free black barber had less to do with education and color. Rather, runaways needed to don the mask of the deferential black barber. Generally, if they maintained good relationships with white patrons, they had a better chance of gaining their protection.

While being able to reach out to white benefactors could be useful, black barbers and the larger slave community had sharper and more reliable resources at their fingertips. In fact, when it came to running for freedom, everyone could be a barber where the razor and the shop facilitated critical instruments and spaces for protection. Enslaved barbers exercised their urban mobility and freedom from surveillance in the city, but neither urban nor rural slaves needed to be barbers to carry or use a razor. Slaves shaved themselves in the slave quarters and their urban environments, making razors readily available grooming instruments or weapons. When Charles Rodgers set out to escape from his master Elijah J. Johnson of Baltimore County, Maryland, his weapon of choice for protection was a “heavy, leaden ball and a razor.”92 It is unknown if Charles was a barber, but if he had to use the razor, lather and professional skill would have been unnecessary. William Grose also understood the dangerous journey ahead when he planned to leave his condition as a house servant in New Orleans. “I can't die but once,” he reasoned, “if they catch me, they can but kill me: I'll defend myself as far as I can.” Grose armed himself with an “old razor.”93 If blacks could use the razor to earn money, cultivate white networks, or cut a slave catcher, the barber shop served similar purposes.

Free black barbers did not strike white patrons who sat defenseless in the barber's chair, but these patrons were mistaken if they believed their power over their barbers was absolute. Despite the specter of redress from white patrons, free black barbers reached out to the slave and fugitive community, if not by day, then by night. John Brown escaped from slavery in search of freedom, which for him meant England. On his journey, he arrived in Paducah, Kentucky, “when few people were about,” and specifically searched for a barber shop for refuge. “In the United States, the barbers are generally coloured men,” he wrote in his published narrative, “and I concluded I should be in safer hands with one of my own race.” After “peeping in at doors and windows,” Brown saw a black man inside of a barber shop. The man opened the door for Brown, but immediately locked it behind him upon entering. He took this caution not only for Brown's safety but also for his own. He sensed Brown was a runaway and vowed to help him keep moving. According to Brown, the barber warned, “You mustn't stop here: it would be dangerous for both of us. You can sleep here to-night, however, and I will try to get you away in the morning. But if you were seen, and it were found out I was helping you off, it would break me up.” Despite the risks, the barber gave Brown food, a place to sleep, and, after making inquiries, provided him with information on a steamer leaving for New Orleans the next day.94 He did not realize England was the opposite direction. Nonetheless, when Brown recounted these events in his narrative, he did not identify the barber or the shop. This kind of assistance extended to the seas as well. Free black barbers along with other black men who worked on steamboats drew on their extensive networks in various river towns to act as conduits of information and assist fugitives. For instance, free black barber Shelton Morris coordinated escapes while he worked on an Ohio River steamboat.95

After slaves escaped to the North, they realized that the road to freedom would be neither smooth nor solitary. It required the help of many people at every turn. Free black barbers were active in the abolitionist movement as organizers and participants in sheltering fugitives in cities such as Philadelphia, Boston, New York, and Cincinnati. The political leanings of black barbers active in the abolitionist movement varied as much as the larger movement itself. In the 1820s, William Lloyd Garrison found strong supporters among black barbers. When James Forten learned that Garrison had established an abolitionist newspaper, the Liberator, he wrote Garrison to express support and suggested that Joseph Cassey would be a formidable agent in obtaining “many Subscribers.” Cassey was a barber and the first Liberator agent in Philadelphia. Garrison acknowledged Cassey's early support in helping get the paper off the ground, noting “if not for [Cassey's] zeal, fidelity, and promptness with which he executed his trust, the Liberator could not have completed its first [year].”96 Barbers were key agents for Garrison's paper. John Burr joined Cassey in distributing the paper in Philadelphia. It is likely they were not the only two of approximately sixty-two black shop owners to assist Garrison.97 In the Northeast, Alfred Niger distributed the paper in Providence, Rhode Island, and Garrison had a host of barbers to share his abolitionist paper in Boston. Barbers were key individuals to distribute the newspaper because they came in contact with a number of people in their shops and in other networks of their lives.

Beyond distributing newspapers, many of the prominent barbers of the antebellum period worked actively with abolitionist societies and lent their shop space to the freedom struggle. In the 1830s, the abolitionist movement entered its radical phase where white abolitionists began shifting their position from gradual and compensated emancipation to immediate abolition.98 Black barbers demonstrated they were far from mere bystanders in this more aggressive movement. The vigilance committees established in New York in 1835, in Philadelphia in 1837, and in Boston in 1846 operated openly to assist free persons of color and runaways. Some barbers actively assisted in such committees and organizations. For example, in 1833, John Vashon helped establish the Anti-Slavery Society of Pittsburgh.99 Far more barbers, however, used their shops as spaces for the abolitionist struggle.100 Shortly after Lewis Woodson arrived in Pittsburgh in 1815, he helped establish the Bethel A.M.E. Church on the corner of Water and Smithfield Streets—the first black church west of the Allegheny Mountains. Fugitives passing through Pittsburgh found refuge in the church and among its members.101 Moreover, when slave owners traveled to Pittsburgh, they often stayed downtown at the Monongahela House and the Merchants’ Hotel at the corner of Third and Smithfield Streets. Those traveling with their slaves unknowingly faced a very organized network of black service workers. Black workers in these hotels shuttled these slaves, who were looking to escape, from the hotel around the corner to Vashon's City Baths or John Peck's Oyster House. From here, they were sent north on one of the escape routes.102 This kind of assistance was not limited to big cities. Fugitives who made their way through Sandusky, Ohio, between Cleveland and Toledo, found barber shop owner Grant Richie very active among the town's one hundred black residents to assist them on their journey to freedom.103

Many barbers, perhaps, calculated their level of involvement based on their customer base or the likelihood of economic reprisals. Northern barbers had three potential sets of customers: the small black male community and white male abolitionists who supported black equality and those who opposed it. Peter Howard's shop attracted black and white abolitionists, providing him more freedom to use his shop as a vessel to openly discuss the abolitionist movement and house fugitives. Other barbers risked the disapproval and loss of white patronage in their shops for aiding the Underground Railroad and vigilance committees. A majority of the participants were skilled and professional workers such as tailors, oyster dealers, carpenters, merchants, dentists, druggists, and ministers.104 They exercised a little economic independence in their work day, and some of them owned spaces, such as barber shops and churches, conducive to housing or shuttling people through the city. Yet clergymen, judges, and professors faced economic reprisals from those in power who disagreed with abolitionism.105 To be sure, unskilled workers were equally active in the movement by opening their homes and passing along information. Beyond the community of abolitionists in barber shops or the potential reprisals some barbers faced, the other segment of potential patrons included slave catchers and slave owners who traveled north in search of their “property” and took a minute to get shaved or simply search for information. The entire black and abolitionist community needed to work together, especially when the federal government tightened fugitive slave laws.

When Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Law in 1850, southern slaveholders received federal support to recover their property, forcing some blacks to flee and others to stand strong. Unlike the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, the new law subjected law-enforcement officials to a $1,000 fine if they refused to arrest a runaway slave, and any citizen who aided a runaway slave was also liable for a $1,000 fine and six months in prison. Slave owners needed only to provide an affidavit as evidence, while the alleged runaway was denied trial and could not refute the charges. The law gave slave owners federal backing to travel with their slaves to northern cities without fear of losing them and to head north to recover runaways. The law also opened a market for slave catchers looking to profit from the rewards for returning runaways. Fugitive slaves headed farther north in droves, particularly to Canada and England, where they could be out of slavery's reach. The black and white abolitionist community stood poised to protect fugitives and resist the slaveholders and slave catchers.

Fugitive slaves who worked as barbers ran the risk that a white customer, perhaps one they had yet to form a close relationship with, would discover their status and inform authorities. In some cases, fugitives relied on the shop owner. In late 1850, George White had been apprenticing as a barber under John Vashon in Pittsburgh. Considering Vashon's work in the abolitionist movement and Pittsburgh's Underground Railroad, he was likely aware that White had escaped slavery. This, of course, was not a problem until White's former owner, Mr. Rose, came into shop looking for a shave. Rose traveled to Pittsburgh from Wellsburg, Virginia, on a business trip. While in Vashon's shop, he recognized White as his runaway slave who, on January 14, 1851, was subsequently apprehended. Vashon quickly stepped in to help White achieve his freedom. He purchased White for $200 only to then set him free.106 Other barbers were not so lucky. In 1854, word spread that two men from Virginia had arrived in Manchester, New Hampshire, looking for fugitive slave Edwin Moore, who had established a barber shop in the city. After hearing of their arrival, Moore boarded a train to Canada with his wife and three children.107 John Thompson spent his early years as a slave in Fauquier County, Virginia, but seized his opportunities for freedom. Thompson had twice escaped slavery; once after being sold to a Huntsville, Alabama, cotton planter, and again after being purchased by a slave trader from Richmond. In October 1857, the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee assisted Thompson on this second escape, sending him through the Underground Railroad; he eventually settled in New York and worked as a barber. Thompson reported to be “doing very well” as a barber, but in December 1860 he was forced to leave the shop and the city behind because someone had informed his master, who had been in the city searching for him, of his whereabouts. After this scare, Thompson was “obliged to sail for England.”108 The culprit who betrayed John Thompson could have been anyone, from a customer to someone simply looking for a financial reward.