CHAPTER 2

The Politics of “Color-Line” Barber Shops After the Civil War

IN the summer of 1918, Harlem Renaissance writer and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston earned money to pay for tuition at Howard University by manicuring the hands of white politicians, bankers, and members of the press who frequented George Robinson's barber shop on 1410 G Street, N.W., in Washington, D.C. She worked alongside another manicurist, ten barbers, and three porters, all black. This Virginia-born mixed-race barber, according to Hurston, owned nine shops in the city, but only one was in the black community.1

One afternoon that summer, a black man entered the shop, which caused confusion before he uttered a word. Nathaniel Banks, the manager and the barber with the chair closest to the door, overcame his surprise and asked the man what he wanted in this barber shop. “Hair-cut and shave,” he replied. Banks, astonished, still tried to be helpful, or so he thought. “But you can't get no hair-cut and shave here. Mr. Robinson has a fine shop for Negroes on U Street near Fifteenth.” The U Street corridor was a vibrant black business and entertainment district in the Shaw neighborhood, which was considered the center of black life and culture before Harlem assumed this designation in the 1920s. In fact, Robinson lived on U Street. The man understood there was a black side of town, but he referenced the Constitution of the United States to claim a seat in Robinson's shop downtown. As Banks began to gently escort the man out of the chair, he attempted to frame the issue around hair type. “I don't know how to cut your hair, I was trained on straight hair. Nobody in here knows how.” Refusing to accept this premise, the protester shot back, “Oh, don't hand me that stuff! Don't be such an Uncle Tom. These things have got to be broken up,” he continued as he tried to force his way into another barber's chair.2

The barber was probably indeed trained on straight hair, because most of the leading black barbers from the Civil War to the early twentieth century groomed only white men in their commercial shops. But it is unlikely the barber could not cut this man's hair. With the decision to serve white men, Robinson and other black barbers, like their antebellum counterparts, had to deny service to black customers because many white men would not be shaved with the same razor or cut with the same shears that touched the face or head of a black man. More important, white men objected to any perception of social equality this practice might portray. Black critics often labeled barbers like Robinson “color-line” barbers for shaving white men at the expense of black men. These “color-line” barbers traded deference for dollars; however, they worked in a less than free market economy that left them in a precarious position. By 1918, color-line barbers were no longer predominant among black barbers, but many of them were still in business. Hurston described how the rejected black man refused to submit until the black barbers, porters, and white customers threw him out of the shop and into the middle of G Street. Hurston neither reprimanded the protester nor participated in the “melee.” “But,” she admitted, “I wanted him thrown out, too. My business was threatened.”3 Hurston was not a neutral observer; she stood to lose money along with the male workers in the shop.

This incident was emblematic of how color-line barber shops stood as contested sites of public space, racial intimacy, and economic freedom. Incidents such as this had occurred many times over in several southern and northern cities after the Civil War and into the twentieth century because the meanings of freedom contained individual and collective interests. Barbers’ relationships with their customers after Reconstruction evolved into a socioeconomic exchange characterized by unequal relations where white patrons’ control was less direct and more ambiguous. This patron-clientage encompassed an informal system of reciprocity organized in a public-private sphere that mirrored social relations that white society attempted to recreate in slavery's image between white and black men in the larger public sphere. In other words, barbers served as clients in their own shops where white men exercised much more power as patrons. Clients depend on their patrons for some tangible or intangible resource. Patrons dictated the rules and clients were benefactors if they maintained what historian William Chafe called an “etiquette of civility” or acceptable behavior.4 White patrons tacitly recognized black barbers’ independence, yet they required the barber shop to be an exclusive space for the white elite. They consumed personal grooming services, but in a way that reproduced antebellum images of racial superiority. By catering to the white elite, color-line barbers attempted to balance their own class ambitions with black collective struggles for respectability and civil rights.

As potential patrons, black men were not a part of the waiting public inside the shop; they were waiting on the outside looking in. Yet they contested these barbers in their shops, in the political sphere, in newspapers, and even in fiction, in the process revealing the larger implications of color-line barber shops for African American freedom. Color-line barbers’ negotiation of the patron-client relationship underscores the larger systematic targets of civil rights struggles, particularly when barbers’ self-interests deviated from the interests of the larger black community, such as the struggles over the Civil Rights Act of 1875.

Black barbers, white patrons, and the American public drew different conclusions on the intersection of race, class, and manhood during shaving-time, a moment in the shop when race relations were betwixt and between. Black barbering in the post-Emancipation period thus suggests that the struggle for equality was both an inter- and intraracial struggle, the latter hinging on competing visions of racial solidarity, class mobility, and black manhood.

Black Barbering in a Free Society

All workers cherished reaping the fruits of their labor, but it was especially so for black southerners released from the inhumanity of bondage. The end of slavery left blacks and whites battling over the meanings of freedom, and economic independence was chief among the claims that freed people deemed central in moving away from the dependency of slavery.5 While the major battles over economic autonomy centered on land ownership and the injustices of the sharecropping system, black skilled, personal, and domestic service workers also tried to remake their economic lives to their own benefit in nonagricultural work in urban areas or resort towns.6 Those who had worked skilled jobs during slavery continued in these employments, while others sought apprenticeships. Black urban workers faced sharp difficulties obtaining industrial and highly skilled jobs because of white labor competition. However, the semi-skilled, unskilled, and generally less desirable jobs were left wide open: waiter, cook, domestic servant, porter, barber, and a host of other occupations. Many freedmen and freedwomen transformed their marketable skills into businesses in the post-Emancipation period.

Table 1. Total Number of Barbers in Select Cities by Race, 1880

Source: U.S. Census.

In the decades after the Civil War, the demographics of the barbering industry looked radically different in the North and South. Black barbers continued to compete with German and Irish immigrants in the North, but they dominated the trade in the South. According to the 1880 U.S. Census, first-and second-generation Germans accounted for 41 percent or more of the barbers classified as white in northern cities. While Cleveland had just over half the number of black barbers that were in New York City, blacks in Cleveland actually accounted for a higher percentage of the total barbers in their city. Most striking about the northern census data is the large number of black barbers in Philadelphia compared with other cities. As early as 1856, the number of black barbers in the city was high (248) and continued to grow.7 Unlike in the North, black barbers dominated the industry in the South. Southern whites still perceived domestic and personal service work as “Negro jobs,” because former slaves had performed such work, and it required a level of deference.8 Unaffected by white competition, southern black barbers had a sense of economic security.9 Black barbers saw opportunities that white men would not allow themselves to see.

Although black barbers constituted a minority in the North and a majority in the South, shaving only white men proved to be the prevailing practice in both regions. Northern barbers who contemplated serving black men faced a small market because a majority of the black population resided in the South. Southern black barbers, in contrast, targeted white customers to maximize their income potential. If barbers had committed to a black market, they would have faced a considerable challenge in attracting white customers. Personal service entrepreneurs—barbers, caterers, tailors—who catered to wealthy whites were still considered the elite among black workers and entrepreneurs, which placed them among the small northern and southern black middle class. African Americans who had been free before the Civil War generally remained at the top of post-Emancipation black society in the South.10 Barbers who were among the black elite were typically of mixed race or very light skinned, born free or freed before the war, and maintained contact with white benefactors.11 White patrons who submitted their chins to their black barbers certainly hoped they had the skill to shave them without incident.

Some black boys entered barbering because they had worked in their father's or uncle's shop to contribute to the household economy. Bill Reese practically grew up in the barber shop. In 1869, six-year-old Reese worked in his father's shop in Athens, Georgia, during a period when “colored children learns [sic] to work mighty early.” Reese performed such tasks as “taking pa's meals to the barber shop, sweeping out the shop, washing spittoons, and shining shoes.” He worked there throughout his childhood and relinquished his earnings to his mother to cover household expenses. By the time he was twelve he “made from a dollar-and-a-half to as high as three dollars in one week.” This was very little money at the time, but it does not appear that Reese worked full time or received full pay. Although he did not state how he was paid, since he turned over his earnings to his mother, his father probably allowed him to keep the tips. He had also been working in his uncle's shop, where he might have received a portion of his intake and tips.12

Not all barbers had prior ties to family shops. Many actually entered barbering as one of the available skilled trades in their search for work in urban areas. At age eighteen, John Merrick, born into slavery in 1859, left Sampson County, North Carolina, to look for work in Raleigh. Although he found work as a bricklayer, he had to make up for the downtime in the winter. The barber shop provided more secure, steady employment. He worked as a bootblack and porter in W. G. Otley's barber shop, where Merrick's eventual business partner, John Wright, worked as a foreman. After spending considerable time in the shop, Merrick began to learn barbering.13 Not all rural blacks waited to get to the city before taking up the razor. Alonzo Herndon was born in 1858 in Walton County, Georgia. At age twenty, he moved to Covington, Georgia, where he worked as a farmhand and also cut hair on Saturday afternoons. He rented a small space in the town's black section to learn the trade.14

Wage and seasonal workers also saw the same security that agricultural workers saw in barbering, which was just as worthy as the professions. George Myers was born in the free black community of Baltimore on March 5, 1859. His father, Isaac Myers, a formidable predecessor to twentieth-century black labor organizers Frank Crosswaith and A. Philip Randolph, urged black workers to organize black cooperatives and fought against segregation in unions. George later developed a more conservative stance on black union organizing. He attended public school in Providence, Rhode Island, a preparatory school of Lincoln University in Chester, Pennsylvania, and completed high school in Baltimore. While his father wanted him to continue his education to study medicine, his formal schooling ended when he realized blacks could not enroll in Baltimore's city college. Instead of training his hands to use scalpels, in 1875 he first apprenticed as a house painter, then as a barber. At the age of twenty in 1879, Myers moved to Cleveland and secured a position as foreman in James E. Benson's barber shop at the Weddell House located between Superior and Bank Streets. Benson, a thirty-year-old mixed-race migrant from Virginia, had recently assumed the lease there.15

Beyond escaping wage labor and sharecropping, some black journeymen used barbering as a platform to other, more desirable, labors. For example, several black politicians during Reconstruction had been barbers before entering politics. According to historian Eric Foner, fifty-five southern black barbers held local or national office during Reconstruction. A majority of these barbers were elected to office in South Carolina, North Carolina, Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi. Thirty-eight of these men were mixed race, and thirteen were black. Forty-two of them reported being literate. Seventeen were born free, and ten were born slave but were freed before Emancipation.16 To be sure, black laborers and veterans made up a large component of elected officials in Reconstruction politics. The black men who occupied leadership positions in the antebellum period (such as ministers, barbers, and abolitionists) may have sustained these positions after the Civil War by helping to organize black political conventions, which put them in positions to be elected to political office. However, considering the status and wealth that black barbers held in the antebellum period, fifty-five former barbers elected to political office are not many. Black southerners had redefined political leadership after the Civil War, where wealth and status no longer held a symbiotic relationship with racial leadership. This applied particularly to barbers, who had established their careers grooming the white southern aristocracy, compared with the black Union Army veterans who fought for freedom and the death of slavery. This is not to suggest that some black barbers, particularly elite barbers, did not assume leadership positions. Rather, black southerners had begun to redefine the basis of black community leadership at the local and the national levels, including women, laborers, and veterans.17 That many of these barbers left the trade behind as they entered politics, perhaps, suggests their own understandings of racial advancement in free societies.

If barbering was a fine temporary occupation for some, it was a clear path to business ownership and economic independence for others. In 1877, Reese's uncle sold him the shop, placing him in the ranks of the entrepreneurial class at the youthful age of fourteen. The racial makeup of his uncle's clientele is unknown, but Reese explicitly noted that he “catered to colored people.” If his uncle groomed white patrons, Reese's change of clientele would have been a major overhaul of the shop. Reese described 1870s Athens as a “little village” with one business street.18 There were likely only a few shops in this small town where most black residents went to Reese's shop—that he mentioned he catered to black customers suggests that this was not the norm—and the white residents went to another black-owned shop.

This young business owner would have had a steep learning curve in managing the shop. But the only difference between being a journeyman and an owner was that a journeyman gave a percentage of his earnings to the owner. Owners paid their barbers a percentage of the barber's receipts. Reese worked on the “check system” and received fifty cents of every dollar he took in. After shaving or cutting a customer's hair, Reese and the other barbers wrote out a ticket for the payment before submitting the money to the owner. On Saturday night, the owner checked the week's gross income against each barber's tickets. Reese preferred this system because “the man that brings the most business to the shop gets the most money.”19 He did not indicate his average weekly income, but during this same period, George Knox, of Indianapolis, paid his barbers between $11 and $15 per week.20 Unskilled wage laborers earned as low as eighty-six cents per day, or just over $4 per week. W. E. B. Du Bois, in his study of Philadelphia in the 1890s, reported that a cementer received “$1.75 a day; white working men get $2–$3.”21 Given the population difference and urban setting, a barber in Athens would probably have earned less than one who worked in Indianapolis. By the turn of the century, barbers received a weekly minimum guarantee plus a commission, or a percentage of the receipts of their chair exceeding a stated figure. This stated figure covered shop expenses, while the “over money” amounted to profits each barber generated, which the barber and shop owner shared. Thus, a barber might receive $15 to $25 per week plus 60 percent of the receipts he brought in exceeding $35.22

Barbers were not the only employees the owner kept on payroll. Barber shops consisted of a wide range of employees to attend to the various needs of the shop and its customers. A foreman managed the daily activities of the shop, including opening and closing, and ensured that customers were serviced well and barbers maintained high morale. A porter collected patrons’ coats and hats to hang up, gathered the tips, and brushed loose hair off their clothing. At smaller shops, one person performed the work of foreman and porter, but larger shops of fifteen or more chairs hired different men for these duties. Employees for non-grooming services included bootblacks who shined shoes and attendants of the bathhouses for shops large enough to offer such services before plumbing became common in American homes. Many barbers actually started out in these positions before learning the barbering trade. Larger shops also hired female manicurists.

Barbers with visions of entrepreneurship had a realistic opportunity to establish their own shops because of the low economic and racial barriers to entry. Although journeymen barbers received low wages, the time and cost to move from a journeyman to a proprietor were minimal. In 1899, W. E. B. Du Bois surveyed 162 black barber shop owners nationally for his Negro in Business report. Their average startup capital ranged from $100 to $500, and they invested an average of $1,200 in their shops.23 Other, more prominent barbers opened their shops with $2,000 to $3,000. The average shop was furnished with two to three wooden barber chairs and sitting chairs for waiting patrons. The owner also needed essential tools such as mirrors, soap for softening beards, shaving cups and brushes, razors, and combs.24 In addition to wages and equipment costs, owners had to consider rent. In the small town of Athens, in 1877, Reese paid $4 per month for a “little upstairs place.” Four years later, he moved downstairs to the first floor of the same building on Jackson Street and paid $10 per month.25 A street-level shop was in greater demand because it benefited from the foot traffic. Reese was probably correct in believing his income would increase at a greater rate than his rent. Barbers in larger cities could expect to pay substantially more than Reese for the monthly rent.

Barber shops attended to the grooming needs of their customers, but the array of services they offered varied based on their capitalization, location, and customer base. White men still frequented barber shops for shaves because the average person lacked the skills to strop and use the straight razor at home. Although it was easier and cheaper for a friend or family member to cut a man's hair, middle- and upper-class men paid for these services. The average price of a shave was five to ten cents, a haircut was fifteen to twenty cents, and a shampoo averaged fifteen cents.26 Based on barber Alonzo Herndon's 1902 account book, many of his customers visited the shop daily, most likely for shaves, but also for other services.27

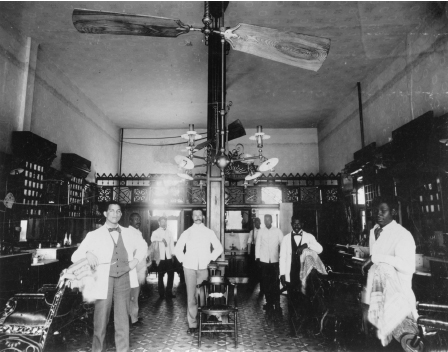

Figure 4. Alonzo Herndon's barber shop at the Markham House Hotel, 1895. Herndon is standing in the center of the shop surrounded by his fellow barbers. Courtesy of The Herndon Foundation.

Southern black barbers capitalized on the growth of New South cities, such as Durham and Atlanta, which brought moneyed men to town. Barbers saw opportunities to service the gentility of the Lost Cause.28 White men and women enjoyed being served by blacks as one of the reminders of the genteel privileges of the Old South. Julian S. Carr and Washington Duke (organizer of the American Tobacco Company) traveled to Raleigh for shaves and haircuts because of “unsatisfactory” service in Durham. Instead of continuing to travel to their barber, they brought their barber to them by encouraging Merrick and his senior colleague, John Wright, to open a shop that “wealthy white men deserved” in the New South city. In 1880, Wright seized the opportunity to continue grooming these industrialists and recalled that he and Merrick “struck Durham about the time she was on her boom.” Duke and Carr were key to this boom, particularly in the tobacco and textile industries.29 Six months later, Merrick purchased half interest, and they worked as partners until 1892, when Wright sold his share to Merrick before moving to Washington, D.C. Merrick went on to open several more shops across the city. Like Merrick, Herndon migrated to an emerging city to groom its elite. In 1883, he had settled in Atlanta, where he worked as a journeyman barber in William Dougherty Hutchins's Marietta Street barber shop. Hutchins was one of a few black barbers who owned a shop in Atlanta predating the Civil War. When Herndon arrived there, the city directory listed twenty-eight barber shops; twenty-three of them were black-owned. Henry Rucker, Robert Yancey, and Robert Steele were among the wealthiest black barbers operating in Atlanta.30 Within six months, he purchased a 50 percent interest in Hutchins's shop.31 Herndon eventually opened his own shop and partnered with other barbers while he established himself and became settled enough to handle the expensive downtown rent.

Merrick and Herndon learned early on that grooming former confederates and carpetbaggers required a public deferential demeanor.32 While it is difficult to know exactly what patrons thought, the racial and paternal politics of the period suggest that the line between competent businessman and affectionate servant was blurred. “I came to Atlanta with the determination to succeed,” Herndon noted, “and by careful conscientious work and tactful, polite conduct.” Being “polite” and “tactful” was essential to servicing a white market.33 White southerners highlighted these qualities when speaking of black barbers. The Atlanta Constitution acknowledged William Betts's death in November 1901. Betts had worked as a barber in Atlanta for over forty years, and he partnered with Herndon to own shops on both Whitehall Street and Lloyd Street. The newspaper fondly recalled that Betts was “polite and appreciative. He had no false ideas about the greatness of his race. He looked upon the man he shaved as his friend and gave himself entirely to his occupation…. Always polite to the white man, and never obtruding upon his superiors.”34 Robert Steele used similar language to advertise his services. An ad for his Marietta Street shop in the city directory read: “Polite Attention, First Class Work Always At Bob Steele's Barber Shop.”35 Being polite seems central to any service business; however, whites perceived politeness and deference when attached to black service as signs of inferiority. In fact, this was part of the fantasy white patrons paid for. If former confederates and carpetbaggers sat in black barbers’ chairs for shaves and had an inflated sense of themselves as superior men, then black barbers stood above them poised to take their money.

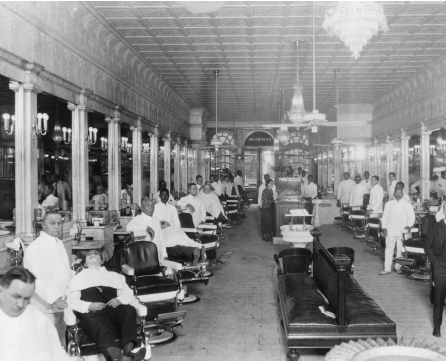

Figure 5. Alonzo Herndon's Crystal Palace Barber Shop at 66 Peachtree Street. Courtesy of The Herndon Foundation.

While black barbers exercised tactfulness toward whites, they negotiated the limits and benefits of these business relationships. One year after Herndon had opened the first A. F. Herndon Barbershop, he accepted an offer from the owner of the Markham House Hotel to become the sole proprietor of its shop. Adjacent to the Union Depot, it was among Atlanta's prominent hotels. Herndon's two-year lease allowed for “water for said baths and barbershop whenever the same runs and there is heat upon the building sufficient, but they are not to run the heat for that especial purpose.”36 He was required to have a white person, merchant John Silvey, guarantee the lease at seventy-five dollars per month. His next two-year lease increased to eighty-three dollars, but did not require Silvey's guarantee. On May 17, 1896, a massive fire burned the entire block where the hotel and barber shop were located. Herndon relocated to the Norcross Building on 4 Marietta Street. Unfortunately, on December 9, 1902, a fire that started around the corner destroyed Herndon's and other businesses on his block. Yet, he recovered quickly. By the following Saturday, Herndon opened another shop on 66 Peachtree Street, named the Crystal Palace, which grew to become his flagship location. By 1904, he owned three barber shops in Atlanta, which at one time employed seventy-five people.37

Like their southern counterparts, northern elite black barbers often got their start through white connections. George Myers opened his shop in the new Hollenden Hotel in Cleveland in 1888 with several loans for his $2,000 startup capital. Liberty Holden, the hotel's owner, lent him 80 percent of the money, and he also received assistance from many future business and political leaders of the city, who were his patrons at his previous shop, such as Leonard C. Hanna (Senator Marcus Hanna's brother) and Tom Johnson (eventual mayor of Cleveland). James Ford Rhodes, historian and eventual president of the American Historical Association, was also among Myers's sponsors. They maintained regular communication outside of the barber shop. In fact, Myers later reminded Rhodes of his kindness, but he refused any credit. “You are mistaken,” he wrote to Myers, “in your notion that I put up any money to start you in business. I did say some good words to Mr. Holden but…‘talk is cheap.’” Myers shared his ledger with Rhodes that accounted for his financial sponsors and noted, “Suffice to say that I paid every one of you gentlemen and through my successful conduct of business and integrity I held the confidence and esteem of all who have passed to their reward.”38 Myers's note to Rhodes provides an early example of how he eschewed long-term debt, financial or otherwise, which was a recurring theme in how he managed relationships.

Although barbers were constrained more by custom than contract in deciding the racial market they would target, they received such considerable business and connections that they were still well represented among the black business leaders in many cities in the late nineteenth century. Color-line barbers’ social status emerged from the potential favors and benefits they might extract from this patron-client relationship—favors and benefits many African Americans hoped barbers would deliver to their communities.39 The tension between barbers’ individual aspirations and black communities’ expectations provided rich material for black literary writers. Charles Chesnutt, novelist and political activist, published The Colonel's Dream in 1905 and “The Doll” in 1912, with color-line barbers as central characters that complicate the everyday tenuous class and gender experiences of these men. Chesnutt reflected on his contemporary moment through literature to render visible the limits and possibilities in the barber shop.

The Colonel's Dream, Chesnutt's last published novel, tells of a retired white merchant, Colonel Henry French, southerner by birth and northerner by achievement, who returns to his old southern town of Clarendon after the Civil War. This New South novel emphasizes the tension between French's liberalism and the southern traditionalism of Clarendon's white residents. Chesnutt explores the limitations of French's northern liberalism through his nostalgia for the Old South, which is piqued through his interaction with black characters. William Nichols, a mixed-race barber, represents an aristocratic figure who serves only white men in his southern barber shop, yet occupies a leadership position in the black community. Through Nichols's relationship with French and Clarendon's black community, Chesnutt suggests that color-line barbers in the New South redefined their relationships with white patrons and capitalized on the racial economy of southern traditionalism for class mobility.

Chesnutt establishes Nichols's elite class status within the black community by emphasizing the resources that accompanied his occupation and wealth. A former slave, Nichols took advantage of a foreclosure and purchased French's childhood mansion for $500 after Emancipation. French realizes a black family resides in his childhood home when a “neatly dressed coloured girl came out on the piazza, [and] seated herself in a rocking-chair with an air of proprietorship.”40

Nichols is cautious and deferential with French, but at the same time he has confidence in his own class mobility and economic resolve. When French sits in Nichols's chair, Nichols engages in pleasantries to gauge his mood; as the narrator suggests, “knowing from experience that white gentlemen, in their intercourse with coloured people, were apt to be, in the local phrase, ‘sometimey,’ or uncertain in their moods.” Nichols introduces himself as one aristocrat to another. “I feels closer to you, suh, than I does to mos’ white folks, because you know, colonel, I'm livin’ in the same house you wuz bawn in.”41 Nichols is deferential yet, in this same breath, he makes a connection—a clever suggestion of social equality—that is forbidden, and legislated against, in southern society. French had fought in the Confederate army to defend the institution of slavery. And the barber, a former slave who is lathering his face and attending to his grooming needs, resides in his home. But, Nichols reveals this news at the very moment he is holding a razor.

After this bombshell, Nichols tells French, “For I loves the aristocracy; an’ I've often tol’ my ol’ lady, ‘Liza,’ says I, ‘ef I'd be'n bawn white I sho’ would ’a’ be'n a ’ristocrat. I feels it in my bones.”42 In reality, for a black man to publicly suggest that he can imagine himself not only as a white man but also as an aristocrat would be an affront on whiteness regardless of class. His affinities for whiteness and upper-class status, he suggests, are not mere chance but natural. Nichols's sentiments about the mansion weigh heavy on French's mind, so he immediately offers to purchase the house at any price. Although Nichols originally had no intention of selling, he is indeed an opportunist and requests $4,000 for the house, to which French agrees, clearing Nichols a handsome profit. French explains his sudden and impulsive purchase to a friend, Laura: “The barber complimented me on the family taste in architecture, and grew sentimental about his associations with the house. This awoke my associations, and the collocation jarred—I was selfish enough to want a monopoly of the associations” (emphasis in original).43 Laura seems mystified that French would dare live in the house after a “coloured family” had lived there. While complimenting the Nichols family as decent people, French still reminisced about the “old” South. “It is no less the old house because the barber has reared his brood beneath its roof,” he argues. “There were always Negroes in it when we were there—the place swarmed with them. Hammer and plane, soap and water, paper and paint, can make it new again…surely a good old house, gone farther astray than ours, might still be redeemed to noble ends.”44 In this paternalistic moment, French still desires the “old” days in the “old” house. He suggests that Nichols—not Nichols the person who was rather upstanding in his view, but Nichols the black barber who cannot possibly keep up the mansion as befits an aristocratic family—cannot bring nobleness and honor to the ownership of such an estate. French, however, is confident he can wash the blackness away.

Chesnutt further complicates our understanding of race, class, and work by reiterating Nichols's ties to Clarendon's black community. Nichols grooms white men and grows wealthy through a shrewd housing purchase, but uses his profits from the house to build a row of small houses for black residents. Nichols also acts the part of the elite. For example, although French's friend, Laura, is mystified that he would live in a home after blacks had resided there, she is secretly employed by the Nichols family as a piano teacher for their daughter. Nichols is party to segregation in his shop, assists black residents with work and housing, and employs a white woman in his home in the late nineteenth-century South. Chesnutt presents the character of a barber whose mask of deference generates resources that ironically permit him to defy southern custom. Individual and group interests are not necessarily irreconcilable: Chesnutt paints the black barber as one who submits to racial deference to sustain his business but is not marginalized from the black community.

While Chesnutt used The Colonel's Dream to illuminate the benefits of class mobility among color-line barbers, he critiqued the competing notions of manhood in “The Doll.” Originally submitted to Atlantic Monthly in 1904 but not published until 1912, the story unmasks shaving-time to conceptualize the tenuous position of color-line barbers.45 Colonel Forsyth, a southern white politician visiting the North for a political convention, seeks to prove his theory of race—that blacks are naturally inferior and submissive—to a northern, white, liberal colleague, Judge Beeman. Forsyth chooses the barber shop in his hotel as the proving ground. He sits in the chair of the black proprietor, Tom Taylor, requests a shave, and proceeds to talk, directly to Beeman, but indirectly to Tom, about his racial ideologies—the natural way of things, eugenics, Darwinism. Tom ignores him until he speaks of killing a black man to “teach him his place.” Forsyth tells the story of a black girl who was accused of misconduct as a servant in his mother's home. The girl complained to her father, who in turn confronted Forsyth's mother and Forsyth himself when he entered the room. Not backing down, the black man continued to defend his daughter until Forsyth shot him.

To Tom, the story sounds eerily familiar. He realizes it was his father Forsyth shot and now this man's neck rests under his razor. Tom is placed in a position he has longed for. He had heard this story before, but a different version. “In his dreams,” according to the narrator, “he had killed this man a hundred times, in a dozen ways.”46 While continuing to shave him, Tom thinks about how he will slice his throat—at what point, at what angle. He also thinks about the consequences of his actions should he take Forsyth's life. He considers himself a “representative man, by whose failure or success [the entire race] would be tested.” He also considers his responsibility to his profession, his shop, and his barbers. Ultimately, he knows he will also suffer; he cannot escape justice, as Forsyth did after killing his father. Tom is on the verge of taking Forsyth's life until he sees the doll his daughter had given him to get repaired. Instantly, Tom thinks of how his violent reaction will affect her life and his own. Forsyth leaves—little does he know, escapes—the chair and the shop, gloating to Beeman, “I never had a better shave in my life. And I prove my theory. The barber is the son of the nigger I shot.”47

Chesnutt, as Melville did with Benito Cereno, paints shaving-time as a moment to illuminate the visible and hidden dynamics of manhood in a public space among barbers, patrons, and waiting publics. Chesnutt problematizes the appearance or performance of deference and humility that was paramount to the livelihood of color-line barbers and other personal service entrepreneurs. Tom's Victorian sensibilities of manliness are defined by independence, character, and restraint, while Forsyth equates resistance with manhood. Because Tom does not resist, according to Forsyth, Tom is cowardly, inferior, and unmanly.48 Chesnutt attempts to complicate the relationship between racial deference and manhood. As a barber, Tom has the ability and opportunity for revenge, but he has no refuge if he does. In turn, he and other color-line barbers learn to survive in a world of racism and segregation. Tom understands manhood as driven by restraint and responsibility. He emphasizes this notion of manhood and citizenship compared with Forsyth's notion that Tom's lack of action was cowardly and unmanly. Although white middle-class men reoriented how they thought about themselves as men, from manliness to masculinity, black middle-class men held onto Victorian definitions of manliness to lay claims to American citizenship. Chesnutt underscores the tensions in race and manhood as identities at the turn of the century.

This barber shop is the site of manly contest; however, the source of Tom's manly restraint is his responsibility to protect his daughter. Tom's manhood is read through his patriarchal responsibilities. Forsyth's blood would stain the other barbers and make it difficult for them to shave other white men. It would send chills down the spines of every white patron who submitted to a black barber's razor, completely altering the trust in the barber-patron relationship. Yet, Tom's decision to take it on the chin instead of carving it on Forsyth's throat went beyond a heavy burden of racial responsibility. The doll represents the central force of his manly responsibility. Even in this homosocial space, in the absence of women, a little girl proves the weightiest anchor that defines Tom's manhood.

“The Doll” also offers a fictional portrait of black-owned barber shops as white public spaces. Forsyth and Beeman talk freely about racial matters inside Tom's shop, appearing to pay little attention to the black barbers. Since we know Forsyth's motivations, we know that he is indeed aware of the barbers. Through Forsyth's discourse and because of his racial ideologies, he at once disavowed Tom's presence and implicitly challenged and monitored his manhood.49 Like Benito Cereno, power relations in “The Doll” are blurred. Barber and patron say very little to each other, but each perceives shaving-time through a racial, gendered lens; not only of the characters, but also of the author. Melville's Babo and Chesnutt's Tom decide not to cut their white patrons’ throats. Babo drew blood, but he needed Cereno alive to continue to mask the revolt. Tom, in contrast, was more constrained. Ultimately, Chesnutt did not have the same creative freedom in Jim Crow America that Melville had as a white writer, to craft black, razor-wielding barbers initiating violent revenge on whites. In “The Doll,” the racial discourse was staged even though the events were true, but, as Chesnutt underscores, Tom walked the line of invisibility and restraint as he observed the conversation and determined how he would wield the power of the razor at that moment.

As Chesnutt's fiction indicates, color-line barbers were uniquely positioned to overhear white racial discourse, a fact that was not lost on barbers or customers, even if they seldom admitted it. Catering to white politicians in Greenfield, Indiana, George Knox built a profitable barber shop across the street from the courthouse. White businessmen and particularly politicians frequented his shop for shaves and to talk politics. “The Democrats would sometimes come into my shop and hold their little councils and caucuses,” Knox recalled. “I would be working away apparently paying no attention to what they would say.” As “apparently” revealed, Knox paid attention. To be sure, he was a staunch Republican attuned to local and national politics. “Some said that I was taking too much interest in politics,” he stated in his autobiography, “it would not be good for my business; I would lose my trade, but I kept right on.”50 That he “kept right on” suggests that he entered the conversations to some extent, unlike the protagonist in “The Doll.” While local politicians may not have welcomed Knox's participation, they knew he listened. In 1875, Henry Wright, a candidate for Hancock County auditor, approached Knox for information on his opponent. “One morning he [Wright] came to me and asked if I had any news that would do him any good. I said if you will come back to my shop at six o’clock in the evening, I think I will have the news you want. He was a strong Democrat and a customer of mine and I always desired to help those who helped me, regardless of their politics. One of the principles of my life has always been to hold old and add new friends.”51 Despite the political views and maneuverings in Knox's barber shop, he cultivated political relationships in a way that did not affect his business.

Men were not the only political conduits inside barber shops. A host of black women also listened to the political discourse of white patrons while manicuring their hands, and in some cases grooming their faces. Zora Neale Hurston's white patrons at George Robinson's shop on G Street in downtown Washington, D.C., included bankers, government officials, and members of the press. These men sat at Hurston's table and talked about “world affairs, national happenings, personalities, the latest quips from the cloak rooms of Congress and such things,” Hurston recalled. “While I worked on one, the others waited, and they all talked.” She believed that they talked so freely because they considered her safe. Other patrons attempted to enlist Hurston's help in gleaning information. One member of the press, according to Hurston, handed her a list of questions to ask particular patrons and to report back their answers. “Each time the questions were answered,” according to Hurston, “but I was told to keep that under my hat, and so I had to turn around and lie and say the man didn't tell me.” She lied to one white man to protect another to ultimately protect herself. Not passing on information was far less egregious than betraying a customer's trust, but the reporter would not rest. “I never realized how serious it was,” she recalled, “until he offered me twenty-five dollars to ask a certain southern Congressmen something and let him know as quickly as possible.” He even tried to seal the deal by offering Hurston a quart of French ice cream. When the Congressman came to the shop the next day, Hurston felt uneasy about the arrangement because he had begun to tell her “how important it was to be honorable at all times and to be trustworthy.” “Besides,” she reasoned, “he was an excellent Greek scholar and translated my entire lesson for me, which was from Xenophon's Cyropaedia, and talked at length on the ancient Greeks and Persians.”52 The reporter never asked again. The intimacy and trust allowed Knox and Hurston to occupy similar positions despite the gender and temporal differences. Yet, they also witnessed sharp critics of the shops and racial policies that facilitated their positions as conduits.

Color-line barbers and manicurists may have been in unique positions to observe the conversations of white businessmen and politicians, but this was no solace to northern and southern blacks who confronted these barbers in person and in print to demand an explanation for excluding black men. In 1873 in Xenia, Ohio, black men protested a local color-line shop. According to the Xenia Gazette, at “about 9 o’clock at night they [blacks] gathered in front of the shop and held a council of war. Finally one of them went in while the others stood guard outside. The leader, who had thus advanced, then planted himself in one of the great chairs and asked the proprietor if he was going to shave him; to which innocent interrogatory the brave barber replied ‘no.’ With this the ruffian let fly a rock at the proprietor, which took effect on his left arm, slightly. There was then a lively hustling about, amongst hands, for a few minutes, and the conflict was over.”53 These men knew they would not be shaved but refused to submit to his policy and were willing to engage in fisticuffs. For protesters, this policy was more than a shameful mark of racial disunity; it was an unmanly display of inferiority that burdened the race. As black men repeatedly challenged black barbers on their racial exclusion policies, their responses revealed the economic dilemmas of race. In 1874 a group of black men was rebuffed after demanding shaves in a Chattanooga, Tennessee, barber shop. After they were asked to leave, they questioned if their money was not as good as a white man's. The barber answered, “Yes, just as good, but there is not enough of it.”54 Certainly, white men, on the whole, had more disposable income than black men. From a purely economic perspective, black barbers were forced to choose between two separate markets, and one was more lucrative than the other.

Color-Line Barber Shops and Reconstruction Politics

Though protests of color-line barber shops existed before the Civil War, the debates over the Civil Rights Act of 1875 raised the political stakes of their existence. Senator Charles Sumner introduced the supplementary Civil Rights bill to grant African Americans equal access to public accommodations, public schools, common carriers, churches, and cemeteries.55 The lengthiest debate occurred in the forty-third Congress, where all seven black congressmen spoke vigorously about their experiences of indignation on train cars, in hotels, and in restaurants. Opponents, armed with the recent 1873 Slaughterhouse decision, rejected the bill as an unconstitutional attempt to interfere with states’ rights and regulate social intercourse between blacks and whites.56 In a lame-duck session, Republicans passed this last act of the Reconstruction era, which guaranteed African Americans equal accommodations in “inns, public conveyances on land or water, theatres, and other places of public amusement.”57 It had to be enforced during the return of white conservative Democratic leadership, however, who had begun to roll back the gains of Reconstruction.58 The Civil Rights Act of 1875 may have passed, but the struggle was hardly over.59

Barber shops were not mentioned in the House debates and were not explicitly listed among the schedule of public places, but this did not deter black travelers. On March 4, 1875, John Hunter, a “rather stout black man,” enjoyed drinks with a friend at the bar of the Willard Hotel in Washington, D.C., located on Pennsylvania Avenue. After they finished drinking, they went into Carter A. Stewart's barber shop inside in the hotel for a shave. In Stewart's absence, his employee turned Hunter and his friend away because only “gentlemen” were shaved at this shop. Moreover, the employee proclaimed, “Waiting on colored men would injure the business of the establishment.” Without argument, Hunter marched to the Police Court and requested a warrant against Stewart for violation of the provisions of the Civil Rights Act enacted three days earlier. The Police Court twice refused to issue Hunter a warrant on the grounds that barber shops were not included in the schedule of public places and therefore did not come under the law.60 The Civil Rights Act was intended to prohibit proprietors, usually white, from discriminating against black consumers in public places of accommodation. However, Carter Stewart was no white proprietor. He was a prominent forty-six-year-old mixed-race barber. He was also among the first black men elected to public office in Washington, D.C., in 1869, representing the first ward in the Board of Common Council.61 But none of this mattered to Hunter, who believed he had the recently passed federal act on his side.62 Having drinks before entering the shop, perhaps, gave Hunter and his friend a moment to collect themselves before seeking a shave and testing the act in Stewart's shop.

African Americans like John Hunter believed a barber shop was no different from a theater or inn, while whites, like authorities in the Police Court, either interpreted the act verbatim or ideologically placed the barber shop as a private business with no charge to public enjoyments. Hunter was among a host of African Americans across the country who immediately tested the new law.63 The week the bill passed, a New York Times editorial noted the changes that Virginia proprietors began making to “evade the law.” The editorial also mentioned, “It is worthy of remark that colored barbers refuse positively to wait on men of their own race. In Richmond several fights have resulted from this refusal.”64 African Americans believed the new Civil Rights Act guaranteed them equal access in white restaurants as well as black barber shops. The act lacked enforcement powers, which left the onus on African Americans to file suit. Proprietors wondered how the law would affect their patronage, and consumers wondered how legal authorities would use their power to define public and private in absence of any clear markers. African Americans questioned the “rights” of private parties and whether or not a business that served the public qualified as a private entity. Reconstruction era debates around the public and private sphere were mostly about political inclusion and white men's efforts to protect white womanhood.65 But the spaces between the ballot box and the home were also battlegrounds for rights and citizenship. It was not long before framers of the Civil Rights Act were called to address its intent with respect to barber shops.

Massachusetts representative Benjamin Butler, a key architect of the bill, addressed “confusions” about the line between private businesses and public spaces. “The trade of the barber is like any other trade, to be carried on by the man who is engaged in it at his own will and pleasure,” he wrote to Harper's Weekly on March 18, “and the Civil Rights Bill has nothing to do, and was intended to have nothing to do, with its exercise. A barber has a right to shave whom he pleases as much as a jeweler has a right to repair a watch for whom he pleases…. These are not public employments, but private businesses, in which the law does not interfere.”66 Butler believed the bill was meant to enforce rights and privileges already granted under common law in places of public amusement, public conveyances, theaters, and inns as businesses for the public. Butler would have been hard pressed to explain how a barber shop or a jewelry shop was not for the public. He understood state definitions of public businesses as enterprises that were licensed by the state. “The theatre and like public amusements,” he argued, “were licensed by the public authorities and protected by the police.” As Butler worked to protect the rights of black consumers, he also worked to protect proprietors, but the public and private rights of both parties were not made any clearer as he attempted to explain them. He opposed “to the utmost of my power any attempt on the part of the colored men to use the Civil Rights Bill as a pretense to interfere with the private business of private parties.”67 He cast his remarks within a narrowly legal framework that addressed venue, but in the debate over the bill itself, he correctly identified the core of the issue. On the House floor before the bill's passage, he had argued: “There is not a white man at the South that would not associate with the negro—all that is required by this bill—if that negro were his servant. He would eat with him, play with her or him as children, be together with them in every way, provided they were slaves. There never has been an objection to such an association. But the moment that you elevate this black man to citizenship from a slave, then immediately he becomes offensive. That is why I say that this prejudice is foolish, unjust, illogical, and ungentlemanly.”68 Despite these sentiments, Butler was not as forthright and candid after the bill passed.

Where protesters read their exclusion as a denial of their civil rights, whites read blacks’ agitation as a desire for social equality. Opponents of the Civil Rights Act argued that Congress had no authority to legislate social intercourse. They believed it was a private matter who whites sat next to on a train, in a restaurant, or in a barber shop. European travelers to the United States in the late nineteenth century commented on this lack of social interaction. James Bryce, a Scottish professor who visited America to study its political system, noted, “He [a black man] is not shaved in a place frequented by white men, not even by a barber of his own color…. Social equality is utterly out of the question.”69 But just what “social equality” meant to blacks and to whites was a matter of debate.

African Americans rejected claims that they were seeking social equality. They stood firm that they could not care less about sitting next to a white person, but simply wanted the right of equal movement and accommodation in the public—for them, social equality was the language used to rally whites to stem civil rights gains. Representative John R. Lynch, an African American congressman and lawyer from Mississippi, addressed this issue on the House floor. “No, Mr. Speaker,” he proclaimed, “it is not social rights that we desire. We have enough of that already. What we ask is protection in the enjoyment of public rights. Rights which are or should be accorded to every citizen alike.”70 Similarly, in 1891, Reverend J. C. Price of Virginia put it plainly: “When a person of negro descent enters a first-class car or restaurant…he does not do it out of a desire to be with white people. He is seeking simply comfort, and not the companionship, or even the presence of whites…. There is no social equality among negroes…culture, moral refinement, and material possessions make a difference among colored people as they do among whites…. The social-equality question is now brought forward because it is considered the most effective stroke of policy for uniting the anglo-saxon people of the country against the manhood rights of the negro.”71 African Americans understood social equality as a society without class distinctions. Whites would not have disagreed that class mattered, but race and gender also guided their use of the term.72 Reverend Price's suspicions were shared by many African Americans, and were violently played out in many southern cities, as seen in the Wilmington riot of 1898 and the Atlanta riot of 1906.

White barber shop patrons drew on the rhetoric of social equality to object to interracial public intimacy and consumer equality. Black barber shops were spaces of consumption and leisure where whites exercised their power as whites, men, and consumers. For them, the plane of social equality stretched horizontally—between consumers—as opposed to vertically—between the consumer and producer, or barber. By marking the barber shop a private space, white patrons protected the social intimacy they enjoyed while hanging out there. Yet, one person's privacy equaled another person's exclusion. By adhering to white patrons’ desires of racial exclusivity, color-line barbers ran the risk of blurring the line between business and racial deference. Barbers advertised their services to a white public, who made no distinctions between the requisites of a service transaction and the requirements of servitude. White consumption in a leisure economy was undergirded with privacy claims to promulgate the fears of social equality. By opposing the Civil Rights Act, color-line barbers guarded their individual economic interests under the umbrella of privacy claims, which proved highly toxic to African Americans’ collective interests in equal rights to public space.

The 1875 federal law was so widely disregarded and contested on the streets and in the courts that in 1883 the United States Supreme Court was forced to rule on its constitutionality.73 The court overturned the 1875 federal act and shifted the responsibility of protecting African Americans’ civil rights to the states. It held the act unconstitutional because Congress could prohibit racial discrimination only by states, not private parties.74 This decision partially assured southern states that the federal government and the court would not interfere with their maneuverings around the Reconstruction amendments, and in many ways it set the stage for the Jim Crow laws of the 1890s. Ironically, Tennessee was the only southern state to enact a civil rights law after the 1883 decision and the first of the southern states to pass a “bona fide Jim Crow law.” Tennessee's Civil Rights Act of 1885 excluded barber shops in its schedule of public places.75

In contrast to the South, many northern states passed civil rights laws to fill this void: Ohio, Iowa, Connecticut, New Jersey (1884); Michigan, Illinois, Minnesota, Indiana, Rhode Island, Nebraska, Massachusetts (1885); Pennsylvania (1887); New York (1893); and Wisconsin (1895).76 Connecticut and Rhode Island passed moderate laws that prohibited discrimination only in public conveyances and places of public accommodation and amusement. Illinois and Minnesota passed more comprehensive laws that explicitly spelled out a long schedule of public places that fell under the civil rights law. Notably, unlike the 1875 federal law, the Illinois, Indiana, and Wisconsin state legislatures explicitly included barber shops in the schedule of public places. Northern states may have been progressive in passing civil rights laws that included barber shops, but racial custom proved too powerful to be curtailed by law.77

Notwithstanding this tension over the intents and purposes of the federal act of 1875 or the state acts post-1883, African Americans in the North had no idea they would have to invoke it against black proprietors. Black protesters in Ohio thought it was ironic that if civil rights laws were actually enforced, it would hurt blacks’ position in the barbering trade.78 “I am a colored man myself,” William Ross of Cincinnati proclaimed, “but can't shave negroes, and that is the reason I don't like the Civil Rights bill.”79 While Ross was mixed race, he did not make this color distinction. He seemed torn between racial affinities and how the state act would cause him to lose his white customers. The irony suggested that civil rights laws were passed to prevent whites from discriminating against blacks in public places. However, black barbers were also discriminating against black men, and theoretically, enforcement of the civil rights laws would have required them to serve black customers, thus driving their white customers away. The struggles for civil rights transcended individual actors, but targeted a larger system of racial exclusion and injustice. In the 1850s, Frederick Douglass predicted this very quandary when he urged blacks to move out of dependent occupations. Whether one was for or against racial exclusion policies in black barber shops, legislation prohibiting discrimination in public places of accommodation demonstrate the paradox inherent in black barbers’ ideologies of self-interest during a period of exclusion and the emergence of Jim Crow.

Color-Line Barbers and the Rules of the Trade

In this highly charged political context, many color-line barbers argued they had no choice but to exclude black men because white men would not patronize a shop where black men were shaved. Barbers often identified this practice as the “rules” or “policy” of the trade. When Reverend J. Francis Robinson arrived in Auburn, New York, just west of Syracuse, in 1889, he was refused a shave at several black-owned barber shops. It is unknown where he traveled from; a year later he assumed the pastorship of Mount Zion First Avenue Baptist Church in Charlottesville, Virginia, which suggests that he may have traveled from the South. He would have been used to the color line in southern barber shops, but perhaps he expected northern barbers to be less constrained. Although he was accompanied by Reverend F. D. Penny of the local Second Baptist Church, who offered the proprietors one dollar to shave his friend, it was useless. “I refused to shave him because it is against the rules of the trade to shave a coloured man,” one barber explained.80 This rule was based on the racial custom that prohibited symbols or signs of social equality. Hence, these were rules made not by the barber, but by the white customers. The language black barbers used to justify these rules, however, created the impression that it was indeed their rule.

Barbers also cited differences in racial characteristics and physical traits to justify this policy. However, they articulated this racialized language to rationalize their policies that made them appear more in control of their business than they actually were. In 1884, a reporter from the Cleveland Gazette, a black newspaper, went to a number of black-owned barber shops in Cincinnati to survey black barbers’ attitudes on “shaving colored men.” That a newspaper investigated this issue illustrates its significance among African Americans in the late nineteenth century. The Gazette staff was conscious of black barbers’ policy of exclusion because the staff undoubtedly made their own decisions on where to get shaved. However, in receiving protest letters from black residents, the paper endeavored to provide color-line barbers an opportunity to explain themselves.

The reporter asked the barbers two questions: “Do you shave colored men here?” and if not, “Why?” Most respondents said they did not serve African Americans. Some cited the demands of their white customers, while others cited racial differences between blacks and whites. Strikingly, these respondents used racialized language to explain their policies. Richard Fortson, a mixed-race barber from Alabama who leased a shop at the Palace Hotel, replied, “No, sir; we have no colored soap, no shears that will cut the wool from the scalp of the coon.” William Handy, a Georgia-born mixed-race shop owner, answered, “No, sir. I am a colored man myself, but can't allow colored men in my shop…. If I shave a colored man white men will not patronize me.” Handy could have let his economic explanation rest. He prefaced his response with a shared racial identity and alluded to a market that was beyond him. But he did not stop there: his immediate response was for a black public, his subsequent reasoning was for whites. Handy continued, “and then again, colored men are harder to shave. You see, when he goes two days without shaving the wool turns back to the skin, and so, you see, we would have to cut each hair twice where we cut a white man's once.” The reporters “fled” to what they considered a more “congenial” neighborhood, but they received the same uncongenial responses.81

According to the reporter, William Ross seemed to run a tight ship in his shop as his barbers stood stoic next to their chairs with their neat white barber's smocks. Ross answered the question as many had before him, “No coon gets shaved here. We have no black soap, and when I went into this business I put up a sign which you can read for yourself: ‘No Nagurs need apply!’” “Color soap” or “black soap” is not to be read literally. They refer to the informal codes of social segregation that personal care products, like soap, were too intimate to be shared between black and white bodies. George E. Hayes proclaimed he shaved black men only if they could pass for white. Unlike the other respondents, Hayes revealed his willingness to negotiate the “rules” of the trade. The Gazette reporters left with the conviction that “the colored man of Cincinnati must shave himself or grow a beard.”82

These responses reveal the precautions color-line barbers took to protect their business in the face of white surveillance. Perhaps white customers were present when the Gazette reporter came around with questions. If so, the barber would have to remain cautious. Yet, the highly racialized language they drew on suggests they may not have responded any differently in whites’ absence. The public nature of the encounter was much too risky for them to respond otherwise, even to a black newspaper reporter. If their white customers did not believe their barber was loyal, then white men's confidence would be shaken and the barber's business might be lost. The power of de facto segregation and racism lies in its ability to work without laws and without direct supervision. It can both exist and not exist at the same time and in the same space. Black barbers operated in a racial public space where their entrepreneurial ambitions were bounded by racial custom.

Perhaps these Cincinnati barbers actually believed that African Americans’ hair was inferior. Fortson, Handy, Watson, and Ross were all of mixed race, and from the South (except Ross). Because of their mixed racial parentage, their own hair might have been straighter, more similar to their white patrons’ than to that of other black men. These barbers acted on a perceived economic rationality that suggested it was more cost efficient to serve white men because of superior racial and physical characteristics. Whatever reasons, racial and social constraints on their independence hindered them from acting on their own free will.

Black critics pointed out color-line barbers’ hypocrisy, especially barbers who made claims about their own blackness or black identity. An 1883 article in the Detroit Plaindealer, a black newspaper, argued, “Though they [barbers] participate in the demands of the race, they hesitate to, and often will not accommodate their fellow man with a shave in their tonsorial parlors. An individual cannot command respect until he respects himself, nor is he entitled to respect until he respects others. Our barbers are unanimous in the cry for equality, but they forget that when they refuse to accommodate a man of their own race they make a shameful and degrading confession that they and their fellowmen are inferior and unworthy of the treatment that the white man receives at their hands.” Suggesting a hard-enough bout against racial prejudice, the article pointed out: “White men take pleasure in calling attention to these facts and ask, ‘you do not count yourselves worthy of equal considerations, why should we consider you so.’”83 This critique had a wide reach that addressed both intra- and interracial conflicts. The writer called for black barbers to be held accountable for their policies. The larger issue was the implications this had for racial progress. As publisher of the Indianapolis Freeman newspaper, George Knox faced a barrage of criticism for claiming to fight for equal rights while excluding black men from his barber shop. Levi Christy, the editor of the Indianapolis World, a rival paper, regularly used his newspaper to charge that Knox had been selected by white political leaders in his barber shop to represent African Americans throughout the state on various racial matters. Christy thought Knox was a poor excuse for a race leader. Christy claimed that he took a “colored gentleman of refinement and ability” to his barber shop, but Knox would not accommodate him when “white men were being entertained.” For Christy, business and racial politics were not mutually exclusive. In an 1892 article in his newspaper, he declared that Knox had a right to choose his patrons, but that “he must be told that he cannot discriminate against his own people and at the same time demand their support. A white man's ‘nigger’ has no place in the respect of decent colored people.”84 The black public understood the racial and class dilemmas of color-line barbers, but many rejected the idea that barbers’ hands were tied.

The opposition, and even the supporters, anchored their critiques in the history of race and capitalism. A Youngstown, Ohio, citizen reminded readers of the Cleveland Gazette “that the object of all men in business is to make money…. His patrons were those who owned the country and had all the money, and who would not tolerate for a moment the right of the colored man to enjoy the same privileges with themselves…. Therefore there was left to the colored man no alternative but to run his business to suit his customers or starve out” (emphasis in the original).85 This respondent argued that altruistic motives had no place in economic exchanges, and race consciousness could not displace profit motives. Some black businessmen who sought to build profitable enterprises on white money accepted the racial constraints on their business decisions. He considered black businessmen “captive capitalists.”86 He posited a notion of economic pragmatism that accepted an unfair society, especially when one's individual profit was at the collective expense of African Americans. While he urged black readers to be sympathetic to capitalism's constraints, another Youngstown resident foreshadowed capitalism's greed. In response to the letter in defense of color-line barbers, this person prioritized the masses over the individual. “No man who has the interest and advancement of his race at heart would conduct his business in a manner that would be detrimental to their interest and progress for the sake of money,” the letter began. “Principle, our love for our people and our desire for their elevation should overbalance our greed for gold.” This person went on to remind readers of one of the world's greatest atrocities at the hands of capitalism. “The motive that actuated those that were engaged in buying and selling our people was the desire for money. The men who do not recognize our rights to-day because of their financial interests are as much our enemies as were the slave dealers of the past.”87 Comparing color-line barbers to slave dealers could not have a driven the point home any harder. But could barbers actually reconcile the incongruence of profit motives and human interests?

Reports from the North, from newspapers and barbers themselves, noted that more shops were beginning to open their doors to black customers in the late 1880s through the early twentieth century. The Western Appeal, a black newspaper in St. Paul, Minnesota, reported in 1887 that “colored barbers in different parts of the country are exhibiting manhood enough to obliterate the color line in their shops. The discriminations which colored men have made in their establishments against colored men, have been one of the biggest stumbling blocks in the way of our obtaining civil rights. No other race of people on Gods green earth treats its members as some of ours do each other.”88 The article failed to indicate in which cities these changes were taking place; presumably St. Paul and Minneapolis were among them. The changes, however, were likely more black-owned shops that welcomed black customers as opposed to shops that boasted an interracial customer base. Well into the early twentieth century, barbers would begin to acknowledge an interracial clientele. According to the Michigan Manual of Freedmen's Progress, published in 1915, Henry Wade Robinson of Ann Arbor, Michigan, serviced the black and white elite and “has completely negated the popular fallacy that in order to be successful in the barber business the boss was required to draw the color line in his patronage.”89 Class and region were important markers for black barbers who served both black and white customers in the same shop. These shops were often referred to, or even advertised, as equal rights shops. Middle-class men were likely the only black men who managed to get a shave in these shops, which was likely the case at George Myers's shop in Cleveland.

Myers was known for shaving the white, not black, business and political elite. Harry Smith and T. Thomas Fortune, editors of the Cleveland Gazette and New York Age, respectively, called Myers the “color line barber” who “refused to shave colored men not guests of the [Hollenden] hotel.”90 However, Richard Robert Wright, president of Georgia State Industrial College, wrote Myers to counter this “libelous” statement and noted, “While passing through your city and not a guest at any hotel, I was shaved in your barber shop…. I do not wish to see an injustice done a good man.”91 It is unclear if the letter was published elsewhere or if Wright simply wanted to privately show him support. Myers mentioned to friend John Green that “in our cosmopolitan shop ‘all customers look alike to us,’ the rich the poor, the high, the lowly, all meet upon a common level and all receive the same prompt polite and courteous treatment, we absolutely make no distinctions.”92 Despite this contention, Myers's manuscript papers suggest that only whites and a few black elite men visited his shop.

Moreover, references or claims to serving black and white customers usually came from black barbers in the North. These northern references to mixed barber shops did not translate well in the South. While visiting the South, European traveler George Campbell related how, during a satirical play in Richmond, a “civil rights man” told of a “civil rights” barber shop in New York where both whites and blacks were shaved. He noted in his journal that the audience appeared to be greatly amused.93 It was uncommon for a white and black man to be shaved side by side.

This southern story was not lost on Paul Laurence Dunbar when he explored the complicated world of the barber in The Sport of the Gods, published in 1902. Joe Hamilton, an eighteen-year-old barber, lives with his parents and younger sister in a small southern town. The narrator describes the Hamiltons as “aristocrats,” with a “neatly furnished, modern house, the house of a typical, good-living negro.”94 His father and mother are both employed as a butler and housekeeper by one of the town's most prosperous white families. Joe earns his living as a barber for white men and, as the narrator suggests, he “rather too early in life bid fair to be a dandy” because of ideas he gleaned from customers. When the patriarch is falsely accused of stealing from his employer and is subsequently imprisoned, the family is completely ostracized by both the white and black communities, which eventually forces them to migrate to Harlem. Although this is ultimately a migration story, Dunbar also examines Joe's movement between white and black cultures as a barber.

Prior to the false imprisonment of his father, Joe does well serving whites and even justifies his choice of clientele by drawing on racialist language to articulate the unattractiveness of a black market. Yet, Joe's status and livelihood are vulnerable to the whims of racism and his own use of racist ideologies. When his father is convicted, Joe is forced to leave his job at the barber shop because of the “looks and gibes” from his fellow barbers. It seems odd the narrator does not mention the reaction of his white customers. Perhaps it is more important for Dunbar to illustrate that Joe is forced to leave by his fellow employees because readers will understand that his white customers will neither sit in his barber's chair nor patronize other barbers in the shop. Joe laments, “Tain't much use, I reckon, trying to get into a bahbah shop where they shave white folks, because all the white folks are down on us.”95 Left with few options, he relents: “I'll try one of the colored shops.”

Joe had once cast fellow black men as the “other,” too lowly to be lathered and shaved by his hands. When he seeks a position at a black-owned and patronized shop, the barbers, in dialect that Dunbar was known for employing in his fiction, remind him of his history of shaving only white men. “Oh, no, suh,” the proprietor responds, “I don't think we got anything fu’ you to do; you're a white man's bahbah. We don't shave nothin’ but niggahs hyeah, an’ we shave ’em in de light o’ day an’ on de groun’ flo’.” Another barber grinningly bellows, “w'y, I hyeah you say dat you couldn't git a paih of sheahs thoo a niggah's naps. You ain't been practisin’ lately, has you?” The proprietor reminds Joe, “I think that I hyeahed you say you wasn't fond o’ grape pickin’. Well, Josy, my son, I wouldn't begin it now.”96 Joe had hurled these racial epithets at black men attempting to get shaved in the shop where he worked. The narrator put it best: “It is strange how all the foolish little vaunting things that a man says in days of prosperity wax a giant crop around him in the days of his adversity.”97 Barbers in the “colored shops” make it clear that Joe has already cast his lot.

Dunbar portrays Joe as a color-line barber in an unstable position in white and black worlds. Although Joe is powerless in negotiating the inter- and intraracial dynamics of the barber shop, the narrator paints Joe's situation as ironic, not tragic. For Dunbar, Joe's self-interest to serve white men is of his own volition because the other black barbers in the novel shaved black men. Joe's character symbolizes the tenuousness of black “elitism,” especially when it was dependent on white support. Dunbar highlights the limitations of catering to a white market and the potential backlash of alienating surrounding black communities. Many barbers separated their work between these two worlds.