CHAPTER 3

Race, Regulation, and the Modern Barber Shop

FANNIE Barrier Williams, a black social worker and reformer in Chicago, insisted in 1905 that white men were organizing to displace “easy-going” black barbers. “When the hordes of…foreign folks began to pour into Chicago,” Williams asserted, “the demand for the Negro's places began. White men have made more of the barber business than did the coloured men, and by organization have driven every Negro barber from the business district. Thus a menial occupation has become a well-organized and genteel business with capital and system behind it.”1 Two decades later William Dabney, a black newspaper editor in Ohio, echoed this opinion when he described how white barbers successfully competed against black barbers in Cincinnati by introducing modern business practices to their shops. “White men came into the barber business,” he began. “The Negro laughed. More white men came. Less laughing. The white man brought business methods…. He gave new names to old things. Sanitary and sterilized became his great words, the open sesame for the coming generation…. Old customers died and then their sons [emerged] ‘who know not Joseph.’…Negro barber shops for white patrons melted as snow before a July sun. White barbers became ‘as thick as autumnal leaves in Valombrosa’ [sic].”2 Dabney and Williams witnessed similar trends and believed black barbers had been on the wrong side of the industry's transformation. Though both gave considerably too much credit to whites’ business acumen, they were right that a new generation of barbers and customers had called into question the old color-line barber shop. White barbers envisioned a new modern shop for the white public, but black barbers, in the North and the South, were not as complacent as the black middle class suggested.

Black barbers faced new challenges as the nineteenth century drew to a close. Increasingly they were obliged to cater to changing business practices, which, in industrializing cities especially, emphasized business efficiency and modern equipment, and to changing styles, as Americans developed a taste for European fashion, food, and luxury. Indeed, the entire industry during the Progressive era assumed a new shape. Immigrants entered the trade in large numbers and formed an international union, technological innovations and modernization changed consumption patterns, and the Progressive-era emphasis on state regulation and professionalization redefined who would be a barber and how barber shops would be managed. Unionization and professional standardization were especially influential in this regard. Through these efforts, it became clear that blacks were positioned outside the boundaries of white barbers’ visions of the modern barber profession.

New Competition

At the turn of the century, black barbers’ leading competitors were first- and second-generation immigrant workers. Writing in the New York Age, a black newspaper, in 1891, Henry C. Dotry reminded black workers that “usually one of the first things foreigners learn after entering upon these shores is prejudice against the Afro-American, and they strive to bar him from various branches of labor.”3 Although northern black barbers had been competing with immigrant barbers since the 1850s, a new expanding economy in northern cities brought even more competitors from Old World countries. In their quest to assimilate into American culture and the American economy, immigrants allied themselves with native white barbers against highly successful color-line barbers for control of a clientele that included white businessmen, merchants, and politicians.

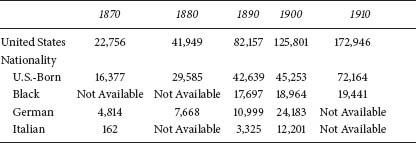

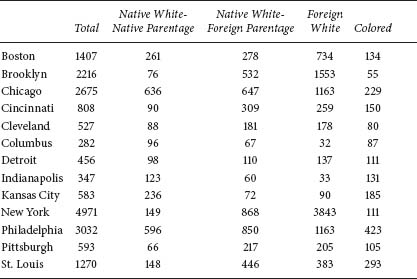

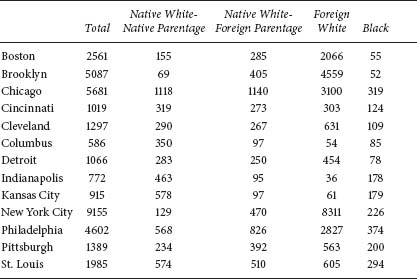

German and Italian immigrants were the fastest growing population of workers entering barbering in the North. Some had been barbers in their native countries, while others entered barbering when they arrived in the United States. If other jobs were scarce or not available, immigrants had little trouble learning to cut hair or shave, and they saved the necessary capital to open their own shops. German immigrants entered barbering in increasing numbers from 1870 to 1900 (Table 2), with a large presence in New York, Illinois, and New Jersey. In 1880, German-born barbers outnumbered U.S.-born barbers 1,604 to 1,508 and represented nearly half of all barbers in the city. In Chicago, Cincinnati, and Pittsburgh, they accounted for one-third of the total barbers.4 Federal census reports include second-generation foreign workers in the “U.S. born” category, which misrepresents the presence of “native” white barbers. If second-generation foreign barbers are included with foreign-born barbers, the number of nonnative white barbers significantly overshadows that of native white barbers in northern cities (Tables 3 and 4). Native white men avoided barbering for two reasons. First, they considered barbering an unskilled, servile occupation. Although the close association between blackness and barbering was not as pronounced in the North as in the South, northern white workers attempted to distance themselves from such service-oriented work. Germans saw entrepreneurial opportunities where white Americans saw disdain.

Table 2. Total Number of Barbers by Nationality and Race, 1870–1910

Source: U.S. Census

Note: Figures for U.S.-born barbers for 1870 and 1880 include native white and black barbers. Subsequent census reports made distinctions. For the 1890–1910 federal census, U.S.-born only includes native whites.

Black barbers had to compete with the growing number of German barbers who were considered more skilled at cutting hair. In The Tonsorial Art Pamphlet, published in 1877, Manuel Vieira noted, “We find many number one shavers among the colored workmen, but in hair cutting they are deficient to a certain extent. The Germans display a great deal of taste in hair cutting and hair dressing, and there are more number one German barbers in this country than of any other nationality, they naturally take to the trade. The Germans take more pains in trying to please their customers.”5 In Vieira's estimation, African Americans’ expertise in shaving made them great shavers, but Germans’ expertise in cutting hair made them great overall barbers. He drew a line between the skilled and unskilled duties of barbers.

While black barbers had to contend with the German competitors, Italian immigrants posed no real threat to their positions in the city. Italians immigrated to the United States in large numbers after the second wave of German immigrants. However, native whites marked the “new immigrants” from southern and eastern Europe—Italians, Jews, and Slavs—as degenerates who were incapable of assimilating.6 Prior to 1890, Italians were not well represented numerically in the barber trade in the North (see Table 2). The huge increase of Italian barbers from 1890 to 1900 reflects a larger Italian immigration flow, which peaked in 1907. Significantly, 58 percent of all Italian barbers in the United States lived in New York, and after a single decade, they outnumbered all barbers in the state. Additionally, the number of Italian barbers in the United States grew to half that of black barbers. The federal census also shows that the number of black barbers increased from 1890 to 1910, but at a slower rate than immigrants and native whites.

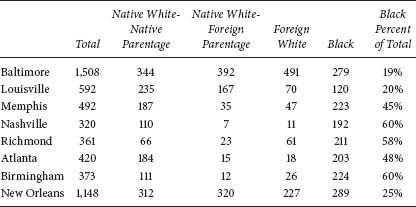

Table 3. Total Number of Barbers in Select Cities by Nationality and Race, 1890

Source: U.S. Census.

Table 4. Total Number of Barbers in Select Cities by Nationality and Race, 1910

Source: U.S. Census.

With the sudden influx of over 7,000 Italian barbers in New York during the 1890s, German and native white barbers grew increasingly concerned about competition. In New York, they lumped Italian and black barbers together as culprits of cut-rate shops. For example, in reports on the enforcement of the Sunday law in New York, the New York Times singled out Italian and black barbers for unfair labor practices and for undercutting prices.7 American nativist barbers were vehemently “outraged” that Italian barbers charged five cents for shaves, below the market price. In June 1895, one hundred “boss barbers” of Brooklyn formed the Boss Barbers’ Association to limit competition. “We are barbers first,” one barber declared, “but we are Americans always!” These white barbers denounced Italian and black barbers as “un-American” because they “take off as much stubble for 5 cents as they [whites] do for 10 and 15 cents, and they concluded that it is a good thing to prevent this competition on at least one day in the week [Sunday].” A “vigilance” committee was appointed to police Italian and black barber shops on Sunday and report violations to the authorities.8 The charge against Italians went beyond pricing structure. Many barbers believed Italians conspired to secretly take over the trade. The New York Times noted, “The Italian barbers, it is said, have adopted a secret trade mark, which they make on each customer's head or face. A small tuft of hair is cut shorter on the back of the head, and another secret mark is made on the face, and thus an Italian barber can tell whether the man he is attending to has been previously handled by an Italian or not.”9 Whites did not view blacks as industry threats because of their small numbers, but they were grouped with Italians for charging lower rates, and thus being “un-American.”

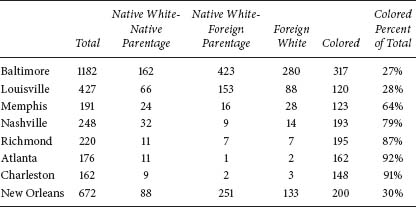

To be sure, blacks were equally worried about Italian (and German) competition in a profession historically dominated by blacks. Black southerners were concerned that immigrants would eventually move South and displace black domestic and service workers. The Richmond Negro Criterion warned, “The foreign immigrants will turn in the direction of the South. When they come, woe, woe to the Negro. The time is fast approaching when domestic employment for females of our race will be as far gone as that of the barber.”10 This concern reflected African Americans’ outlook on systematic discrimination and their vulnerable stake in the market economy. According to the 1880 federal census, German barbers increasingly surfaced in Baltimore and Louisville. In fact, by the 1890s, foreign-born barbers outnumbered black, and native white, barbers in these two cities. Although most southern cities did not witness this trend, one or two immigrant barbers were enough to constitute a rhetorical presence, or a way to articulate the beginnings of a potential market shift.

Table 5. Total Number of Barbers in Select Southern Cities by Nationality and Race, 1890

Source: U.S. Census

Table 6. Total Number of Barbers in Select Southern Cities by Nationality and Race, 1910

Source: U.S. Census.

Black southerners’ fears of being pushed out of the barbering industry were not only targeted at immigrants, but also encompassed a growing contingent of white southerners. Southern states witnessed dramatic increases in native white barbers in the first decade of the twentieth century. In Georgia, the total number of native white barbers quadrupled from 66 in 1890 to 253 in 1900, only to triple to 1,025 by 1910. The number of black barbers increased as well, but at a significantly lower rate. In a twenty-year period, native white barbers in Georgia went from representing 7 percent to 42 percent of the barbers in the state. In North Carolina, the number of native white barbers nearly quadrupled, from 47 in 1890 to 179 in 1900, only to quadruple again in 1910 to 778. They went from representing 9 percent to 45 percent of the barbers in the state. While the number of black barbers decreased in some cities, such as Baltimore, their numbers actually increased in most cities and states. But, because these increases were at a much slower rate than native white and immigrant barbers, the percentage of black barbers to the total number of barbers decreased dramatically. For example, African Americans made up 92 percent of the total barbers in Atlanta in 1890, but twenty years later they made up only 48 percent. Native whites accounted for these percentage changes.

Regardless of their numbers, white barbers still faced the task of convincing white patrons to frequent their shops instead of black shops. A white barber in Durham admitted that they met “a great deal of competition from the Negro Barbers. It was difficult to change the habits of whites that had grown accustomed to particular black barbers. We found it impossible to get them to change to our shops. However poor white men who moved into Durham from the country much preferred our services to that of a Negro, and especially a Negro who was more or less wealthy.”11 In many southern cities at the turn of the century, white supremacists charged that black barbers were taking jobs that “belonged” to white men.12 The traditional southern association of blackness and barbering was beginning to wane. In 1908, Alfred Holt Stone, a white Mississippi cotton planter and racial theorist, argued in Studies in the American Race Problem that despite the southern prejudice for black personal servants, few southern men patronized black shops after “having once tried white shops.” He further believed that white southerners would eventually displace blacks in other service occupations when they learn, “as the Northerner did long ago, that the Negro is not the only race on earth engaged in such occupations.”13 The black middle class, in both the South and North, was convinced that immigrants and native whites “crowded” out black barbers because they failed to exercise efficiency in business management. White men grew more interested in personal service work, but they first wanted to redefine what it meant to service the public.

Facing new competition from immigrant and native-white barbers, color-line barbers with the available resources made extensive and elaborate improvements to their shops. In 1885, the Cleveland Gazette announced the opening of William Ross's new Cincinnati shop, which cost $3,000. This was the same Ross who opposed the Civil Rights Act of 1875 and Ohio's 1884 Civil Rights Act, and was among the respondents in the Gazette's investigation into Cincinnati's color-line barbers a year earlier.14 After his lease at Burnett House expired, he opened his new shop at 158 Walnut. From their “reportorial purview,” the reporters “saw that it has seven of the latest patent barber chairs, finished in deep cardinal silk velvet, with an elegant French mirror dressing case in front and a marble-top washing apparatus attached, furnishing both hot and cold water. The floor is covered with black and white square marble slabs, and in the rear is a large two hundred-dollar anthracite stove of the latest patent, and whose heat makes December as pleasant as May.”15 Ross employed seven men and averaged $200 per month in expenses.

George Myers of Cleveland responded to white competition in the late 1890s by improving the decor and service of his shop. “You see, when I started in the barber business,” he recalled, “there were so many things needed to make shops more sanitary and to serve patrons better, that it wasn't hard to make improvements.” He employed a female manicurist, a chiropodist, and a stenographer for busy professionals. He also installed modern sanitary equipment, comfortable chairs, and even a telephone near each chair. “I used to notice that a man would often become nervous after he had been in the chair a few minutes, as though he had suddenly thought of some important matter that should be taken care of right away,” he explained. “It seemed, too, that many men regretfully took the time to have their barber work done. With the individual telephone, a man can have his barber work on him as long as may be desired without losing a minute. Our operator calls his numbers for him, either local or long distance, giving him the same service that the busiest man has in his own office.”16 With these business decisions, his shop was exceptional among black and white proprietors and earned him a notable reputation. Elbert Hubbard, a journalist, proclaimed the shop “the best barber shop in America,” a phrase Myers adopted and painted across the wall. Myers's shop was indeed a model of the new “modern,” efficient barber shop.17 However, there were few shops across the country where a customer could get a haircut, make a call on his individual telephone, and dictate a memo to a stenographer, all without leaving the barber's chair.

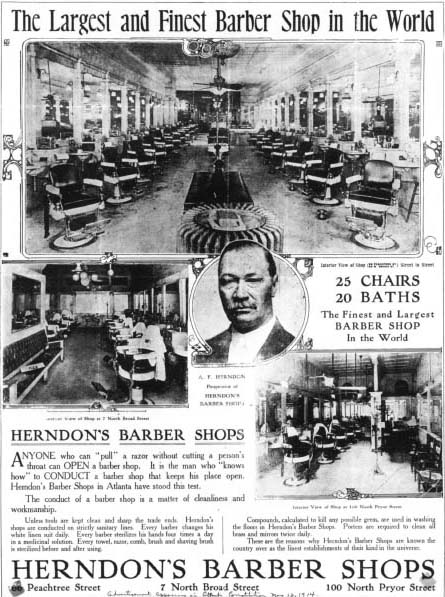

Southern barbers may not have replicated Myer's telephone service, but they joined him and others in making capital improvements to better appeal to their patrons’ modern desires. Barbers accomplished this by equipping their shops with furniture and fixtures imported from Europe to invoke the cosmopolitanism of sartorial consumption.18 At the first National Negro Business League conference, held in Boston in 1900, barber Daniel W. Lucas of Kansas City addressed the convention about the improvements black barbers had accomplished in his city. In his address, titled “Tonsorial Artists,” he noted the large investment he poured into the furnishings and fixtures in his barber shop. Noting the trend to update barber shops, he argued, “The modern up-to-date barber shop of America has a Turkish bath house in connection, and is designed for the pleasure, comfort and luxury [of a] high toned barber shop, with Turkish bathrooms…destined to become more and more like the old Roman baths, a gathering place for luxurious care of the body or person. The possibilities for a colored man in the barber business are great…if he will see to it that he has nothing but what is the best and give better service than any one else.”19 Catering exclusively to local white customers and traveling men, Lucas emphasized modern improvements to recast the barber shop from a place of necessity to one of luxury. In 1913, Alonzo Herndon remodeled and enlarged his shop on Peachtree Street in Atlanta. The new shop included white marble, bronze chandeliers, gold mirrors, and sixteen-foot front doors made of solid mahogany and beveled plate glass. This enormous (24 by 102 feet) barber shop extended an entire city block with twenty-five barber chairs and eighteen baths with tubs and showers on the lower level.20 He used this opportunity to reintroduce whites to all three of his shops by placing an advertisement, with photos, in the Atlanta Constitution. Whether black barbers purchased new fixtures and furnishings in response to the prevailing language of business efficiency and progress or to keep pace with white and black competitors, only the elite barbers could afford large-scale capital investments.

Figure 9. “The Largest and Finest Barber Shop in the World,” Atlanta Constitution, May 12, 1914. Courtesy of The Herndon Foundation.

Despite the major improvements of a few, the average shop owner did not import European fixtures or house a bathing room. At a time when professionalization and efficiency were the buzzwords of modern business, the average barber likely stood out for his lack of progress. Booker T. Washington, founder of the Tuskegee Institute and a prominent black leader in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, consistently pointed out what he thought black business people needed to do to compete with whites. As the foremost booster of black business development, Washington censured blacks, in his 1901 autobiography, for failing to improve barbering while whites “put brains into it.” “Twenty years ago every large and paying barber shop over the country was in the hands of black men, [but] today in all the large cities,” he claimed, “you cannot find a single large or first class barber shop operated by colored men. The black men had had a monopoly of that industry, but had gone on from day to day in the same old monotonous way, without improving anything about the industry. As a result the white man has taken it up, put brains into it, watched all the fine points, improved and progressed until his shop today was not known as a barber shop, but as a tonsorial parlor.”21 He was well aware of Myers's shop and had heard Lucas's address on “Tonsorial Artists” at the NNBL conference a year prior. Washington ignored the several black “first class” shops in major cities to focus more on industry-wide competition. His counsel to barbers was consistent with his larger messages to African Americans, particularly southern agricultural workers, to “cast down your buckets where you are.” He believed black barbers failed to capitalize on technology to secure their place in an industry that few whites historically wanted to enter. The Progressive-era gospel of efficiency lent the black middle class a language with which to explain the influx of white immigrant and native white barbers. But, there were other industry improvements, or “fine points,” to use Washington's words, that affected the terrain on which blacks competed with white barbers.

New commercial shaving equipment for use at home disrupted men's weekly visits to barber shops. Before the twentieth century, most men went to barber shops for shaves rather than haircuts. It was more cumbersome to use the straight razor at home because it was difficult to keep sharp, and most shaving soaps failed to work up a good lather. King Gillette, a Chicago businessman, sought to satisfy the men who did not want to frequent the barber shop daily to save time or money. “There [was] no razor on the market,” he recalled, “that was of such low cost as to permit…the blade being discarded when dull and a new one substituted.”22 Gillette did not invent the first safety razor, but in 1903 he streamlined its production and made it more efficient and cost effective.23 The disposable safety razor threatened to make a trip to the barber shop a luxury rather than a necessity. In the 1930s, African American John Moore of Raleigh, North Carolina, assessed how it was affecting his shop: “I believe safety razors have hurt us more than anything else. Looks like all men have safety razors and they shave at home. Shaving used to be the biggest part of our business. We have to depend on cutting hair for our living now.”24

The commercialization of the safety razor inadvertently broke the link between blackness, service work, and unskilled labor. With the popularity of the Gillette safety razor, men went to the barber less often for shaves, and more attention was placed on cutting hair. This is not to suggest that barbers did not cut hair prior to the twentieth century. However, the changing popularity of hairstyles dictated the frequency of haircuts.25 White barbers considered cutting hair more of a skilled task than shaving. Now, instead of labeling the barber an unskilled worker, white barbers made distinctions between the barber's skilled and unskilled duties. This new articulation of the social meanings of barbering offered possibilities that can best be described as “reskilling” the industry. As white barbers attempted to reskill the industry, or to define themselves as skilled professionals, these job classifications, and who performed them, carried more weight. With less emphasis on the intimate contact of handling a man's face, barbering gained prestige among white men as a skilled craft. Thus, technological innovation contributed to the whitening-up of barbering and shaped the primary work of the barber and the emphasis on his “skill.” The rise of a service ideology provided the preconditions for such notions to take shape. An emerging consumer capitalism, between 1880 and 1915, facilitated the new modern consumer service that corporations, such as department stores, used to invoke ideas of desire and luxury. Merchants recognized that the American marketplace had been undergoing a shift from a production- to a consumer-based society. By 1915, service became a necessary business strategy or, as William Leach notes, “the benevolent side of capitalism,” that would propel profits with customer satisfaction. Yet employees wanted to maintain their dignity in this new project of consumer service.26 For individual white barbers, understanding their labor as skilled work was dignifying, and it made them feel better about engaging in service work. In the larger barbering industry though, white barbers took grander measures to establish professional dignity and authority to position themselves as service workers for an expanding consumer society.

The Industry Organizes

While immigration and the safety razor helped to redraw the demographics of the barbering industry, German journeymen barbers organized to articulate their labor issues. In May of 1869, Fred Tourell led a group of barbers in organizing the Journeymen Barbers’ Union in New York to decrease working hours from fifteen to twelve, observe Sunday as a day off, and increase their two-dollar daily wage. They held several meetings at the German Assembly Rooms in New York throughout the year to encourage German barbers to join this local union.27 This effort grew into the Journeyman Barbers’ International Union of America (JBIUA), founded in 1887 in Buffalo, New York. JBIUA organizers vowed to “make national a reform movement for the correction of abuses,” including “long hours and low wages, Sunday work, and 5 cent shops.” The barbers’ union was unique among trade unions because, in addition to working conditions, it was equally concerned with prices. The union conceded that owners could pay them decent wages only if prices were at market rate. Therefore, it railed against shops that charged “5 cents” for a shave because union shops could not compete for customers, and owners might use this as an excuse to pay lower wages. Many barbers shared these concerns, but the JBIUA was focused on establishing an exclusive body. In its first year, only fifty barbers joined the union, but between 1890 and 1902, membership rose dramatically, from 800 to 16,000. They obtained a charter from the American Federation of Labor, in April 1888, which was yet another move to associate barbering with a skilled occupation. The AFL firmly believed in craft autonomy and allowed affiliated unions to manage their internal affairs without interference.28 For the JBIUA, this decentralization would be critical for its southern locals.

Southern unionizers had a strong incentive to see black barbers organized into the JBIUA. In the North and South, white locals reached agreements with boss barbers on hours, wages, and prices. In a given city, all white-owned barber shops that acknowledged the union agreed to a set wage and price scale. The national body issued union shop cards to these owners to display in their barber shops to foster solidarity among union members in other industries. Owners who did not allow their barbers to organize or agree to the union's standard conditions, particularly pricing, could essentially undercut its price scale, woo customers away from union shops, and potentially hinder organizing efforts. Organizing black barbers was critical in most southern cities because they still outnumbered white barbers at the turn of the century. Yet, organizers were not concerned with all black barbers, only those with a white clientele.

At the union's ninth convention, held in Memphis, Tennessee, on November 8, 1898, its first convention in a southern state, delegates decided they needed to make a concerted effort to organize black barbers.29 The JBIUA sent general organizers on a “tour” of northern and southern states to organize white and black barbers. Whether the organizers attempted to organize one local or separate locals depended on the willingness of both white and black barbers. For instance, black barbers in Mobile, Alabama, resisted organizing with white barbers because black barbers claimed they were already charging higher prices than the white union shops.30 A higher price level would certainly appease the union, but working hours were also central to their efforts. It is also possible that the black barbers who spoke with the union organizer charged lower prices but simply were not interested in talking with him or cooperating with the city's white barbers. In 1898, there were separate locals in Nashville, Tennessee, and Galveston and Houston, Texas.31 Some organizers attempted to establish one local, but most yielded to local racial politics between white and black barbers and organized them in separate locals. Other organizers simply focused on setting up all-white locals, even if they were a minority.

In 1900, the AFL revised a section of its constitution, Article XII, Section VI, to allow central unions, local unions, or federal unions to issue separate charters to black workers if “it appears advisable.”32 In the Journeyman Barber, the AFL defended its policy and efforts of organizing black workers in the South. They claimed that if black workers were denied admission, it was because of their character, not their color.33 In 1903, the JBIUA put forth the same decentralized policy on southern black membership as it did for its northern locals. “Our policy of equality for all skilled members of the craft, irrespective of class, creed or color, has resulted in their [blacks'] organization into unions of their own in the South.”34 Their policy also prohibited northern unions from excluding black members. In Detroit, black barbers were admitted to the local in 1889, but when the local was reorganized after a dormant period, it was all white.35 There were an estimated 1,000 black members of the union in 1903, out of total membership of 20,800.36 Reports in the Journeyman Barber monthly journal claimed that black barbers were sometimes denied admission, but not because of discrimination, since “white men are more often treated in a like manner.”37 In fact, the union heralded its policy as proof that “complete equality” existed in its branches and wondered why the estimated 26,000 black barbers not unionized could not see this.38 To regulate black competition, the union actively attempted to organize black barbers where there were a significant number of black-owned shops effectively competing with white shops.39 Like that of the AFL, the JBIUA's national policy of equality had different results in southern cities. The wording suggested the union accepted the separate-but-equal doctrine that defined southern racial politics at the turn of the century.

While in Savannah, Georgia, in 1912, organizer A. C. Mendell noticed the difficulty of organizing in the South. He stated in his monthly report, “I had made up my mind that I was going to organize the white barbers of the town if it took me a month.” Mendell's energy targeted the few white barbers in the city, instead of the black majority. “The conditions of our craft in this city have been such that it has made it difficult to organize,” he continued. “Many of the first-class shops have been conducted by colored help, some of them owned by white men who still insist in hiring colored men for various reasons. They claim they cannot secure white help enough at any time they need them, but I think the main reason is because they do not want to pay them enough. The colored men are still in a majority in that city and they undoubtedly could be organized, but I made no effort owing to the conflict between the two races.”40 Mendell realized the difficulty in organizing a city with black barbers in the majority. A small white local would have been ineffective in Savannah. Moreover, some white barbers played on the racial preferences of the city's white elite by employing black journeymen to staff their shops, highlighting the difficulties in organizing there. Ultimately, black barbers kept their distance because they were suspicious of the union's motives.

Some southern organizers successfully created separate black locals. In Selma, Alabama, John Hart organized a white local and “all black barbers working on white patrons.”41 Even though W. O. Pinard, a general organizer, noticed the barbers “here are mostly colored,” he successfully organized blacks in Savannah, Georgia, with thirty charter members. Establishing a black local with a few charter members was half the battle. In cities where black barbers were in the majority, organizers needed to convince them of the benefits of operating on the same hours and wage scale as the few white shops.42

Despite the international body's aims, black and white locals rarely worked in concert with each other. Locals 152 (white) and 197 (black) of Little Rock, Arkansas, never agreed on work hours or prices. While white shops affiliated with Local 152 operated on a twelve-hour day, a white barber claimed barbers affiliated with Local 197 “open as soon as they get to the shops and remain open until they get ready to close, which is always from thirty minutes to an hour later than the real union shops work.” He lamented that white barbers were unable to compete with “scab shops” that displace the union shop card because customers would simply patronize these shops for lower prices. What he referred to as scab shops were actually union shops that apparently disagreed with the JBIUA's hours and prices, but members of Local 152 seemed less concerned with the working conditions of the black journeymen who were working these “extra hours.” Since only journeymen were eligible to join the union, Local 152 failed to align with black journeymen to pressure the owner to decrease hours. Similar issues existed in Jackson, Mississippi, and Shreveport, Louisiana.43

According to a survey by the Tennessee Bureau of Labor in 1896, black and white barbers in Nashville worked the same thirteen-hour days, six days per week, but black barbers were paid less than white barbers. Black journeymen earned an average wage of nine dollars per week on the percentage plan. These black-owned shops charged ten cents for shaves and twenty-five cents for haircuts. White journeymen, in contrast, earned an average wage of ten dollars per week. The report accounted for seventy white barbers and fifty black barbers, but it is unclear how many of these black barber shops served a white clientele.44 Since the shops in Nashville's black local catered to white men, and the black and white locals had the same wage scale, it is likely the black shops that catered to black men brought down the average wages of black barbers.

Despite the wage disparity between black and white barbers in Tennessee, barbers in some cities organized into interracial locals. In 1899, Pinard gathered white and black barbers in Chattanooga into one local. Next, he went to Knoxville with “strong hopes of forming one big local,” but was forced to form separate locals.45 Generally, the national organizing body supported incorporating black barbers into white locals. However, organizers usually deferred to the wishes of local white barbers to form separate locals. There were some black and white locals that cooperated to improve working conditions. For example, as the depression of 1893 deepened through the decade, many Nashville barbers ignored the customary practice of closing on Sunday. The black and white locals, however, successfully worked together to pass a local ordinance prohibiting Sunday barbering. This interracial cooperation did little against the numerous barbers who decreased prices to deal with the depression.46

Organizer Leon Worthall summed up the challenges of organizing black barbers in the South: class solidarity could not overcome racial tensions.

We, as part of this great American labor movement, have a rather perplexing problem before us with the colored workers, and I further believe that the only solution is either to organize them with us, or not to bother with them at all. If the colored element is a competing factor in the industry, as such it behooves us to give them a place in our already organized white local and if one is not organized then to organize them into a mixed local, where they can be properly educated into the principles of trade unionism. True that we have places where two locals, one of white and another of colored, are successfully conducted, but even there the sailing is not at all smooth. I hope that the day is not far distant when we as trade unionists will cease to be narrow along economical lines and deal with the colored question on its merits.47

Worthall considered the presence of black barbers a “perplexing problem.” He seemed less concerned with black journeymen increasing their wages and gaining better working conditions. Rather, black journeymen and color-line shop owners were roadblocks to the labor movement, an apparent “problem” that black scholar and activist W. E. B. Du Bois captured eloquently at the time. “Between me and the other world,” Du Bois suggested, “there is ever an unasked question: unasked by some through feelings of delicacy; by others through the difficulty of rightly framing it. All, nevertheless, flutter round it. They approach me in a half-hesitant sort of way, eye me curiously or compassionately, and then, instead of saying directly, How does it feel to be a problem? they say, I know an excellent colored man in my town; or, Do not these Southern outrages make your blood boil? At these I smile, or am interested, or reduce the boiling to a simmer, as the occasion may require. To the real question, How does it feel to be a problem? I answer seldom a word. And yet, being a problem is a strange experience.”48 Many southern black barbers distrusted the organizing efforts of the union, particularly the movement behind barber shop regulation, because African Americans were often posited as a “competing factor,” “perplexing problem,” or “negro problem.”

Black workers were skeptical of most labor unions because they perceived them as organized conspiracies by foreigners to drive them out of traditionally racialized occupations—as barbers, painters, waiters, and coachmen. In 1903, an editorial in the Colored American stated, “The first thing they do after landing and getting rid of their sea legs is to organize to keep the colored man out of the mines, out of the factories, out of the trade unions and out of all kinds of industries of the country.”49 Many black barbers partially blamed the JBIUA for their decline in the profession. George Myers commented to his friend James Ford Rhodes that there were “no unionists” among his twenty-eight employees. “I have little use for Organized Labor,” he proclaimed. “It is inimical to the Negro.”50 He believed class-consciousness among white laborers was an effort to “crowd out” blacks from certain occupations. Like other black leaders, such as Booker T. Washington, Myers associated unions and radicalism with foreign-born workers, which, in his view, threatened the economic progress of black workers.51 He viewed unionization and reform as a disguise for white control. But the JBIUA looked to establish its control by aligning itself with the professional class rather than the working class.

In the late nineteenth century, occupations such as medicine, law, social work, and education initiated formal entry requirements into their fields, which protected their exclusivity and prestige. In the mid-nineteenth century, almost anyone could become a doctor. These “doctors of the people,” historian Robert Wiebe noted, “roamed the land at will.” In the 1890s, doctors began joining local medical organizations and pressured the American Medical Association (AMA) to reorganize in 1901. AMA membership, 8,400 in 1900, rose to over 70,000 by 1910. Other organizations also demanded “modern” scientific safeguards that would limit entry into the field. Also during the period a cadre of new doctors transformed public health into a “profession within a profession.”52 Barbers would soon join the crowd of reformers intent on protecting the public but obsessed with consolidating power and authority in their industry.

The Struggle over Professionalization

The JBIUA was not an association like the AMA, and the ancient days of the beard-shaving, bloodletting, barber-surgeon were long past, but the barbers’ union was equally concerned with professionalizing its field and drew on public health to do it. JBIUA leaders followed suit with the AMA and American Bar Association to create entry requirements where none had previously existed. In the process of professionalizing the trade, they demanded greater emphasis on scientific knowledge of disease, which they believed would enhance the industry's image. In addition, by addressing public health concerns, they increased the likelihood that Progressive-era reformers would support their regulation movement to protect the public from unsanitary barber shops.

By 1900, a number of scientific articles linked certain diseases with unsanitary barber shop practices. In 1903, Scientific American praised New York's law regulating barber shops, which the Board of Health enforced.53 In 1905, Isadore Dyer, M.D., published an article, “The Barber Shop in Society,” warning physicians of the contagious diseases lurking around American barber shops. Dyer argued that various skin and other infectious diseases—syphilis, ringworms, and pus infections, to name a few—could spread to other customers through the brush, comb, razor, shears, or towel.54 One towel was usually used for every twelve customers. He praised Missouri's 1899 barber law, but argued it addressed only cleanliness, not disease prevention. He concluded that the “barber shop is a commodity and as such should be regulated,” and the “public has so long deserved some protection.”55 While considering the shop a commodity was technically inaccurate because men paid for shaves or haircuts, not the shop, Dyer probably meant that purchasing a haircut was not like buying a prepackaged good—and that the tools barbers used to groom one patron (towels and scissors) were also used on another. Most critical for Dyer and other concerned scientists was to ensure that diseases not be passed from customer to customer inside the shop. To this end, reformers relied on government regulation to safeguard public life in a growing urban environment.

Race, public health, and sanitation anchored proposed barbering regulations. In Atlanta, disease and public health were the medium for framing tensions with labor and race relations. Black washerwomen were marked as carriers of contagious disease, particularly tuberculosis. Since they washed white people's clothes in their own front yards, reformers were concerned that the “unsanitary” conditions of black neighborhoods were a breeding ground for disease that could spread to whites through their clothes. Health reformers and politicians regulated washerwomen, initiating licensing laws and bimonthly examinations.56 Through the guise of professionalization, black women's “lives and labors” were policed. Measures to safeguard public health and professionalize domestic work were means of establishing order in the public sphere. Protecting the public, however, meant protecting the white public. Barber shop reformers were equally concerned with protecting the white public from contagious diseases. By showing a concern for public health, the union hoped to find allies among Progressive reformers. Black barbers believed this discourse of public health and sanitation was a facade for driving them out of the field. Since color-line barbers were in the majority in most southern cities, labor organizers made a more concerted effort to organize black barbers catering to white men and build alliances with state legislatures to secure the passage of state licensing laws.

The JBIUA saw regulation as a central component to their larger vision of professionalizing the trade. In 1896 a union officer investigated the training system of barber schools in Chicago. “I found it worse than I had anticipated,” he reported. “I then wrote an article for our Journal, describing the school and advocating laws to provide for examination and licensing of barbers. That was the beginning of the agitation for license laws.”57 This training system was described as a “schemed system” that made an aspiring barber “believe that a six or eight week course would sufficiently fit him for a first-class position, or make him a practical and competent boss barber.”58 He referred to the Arthur Moler Barber College, considered the first barber college in the country, founded in 1893. Moler opened other barber colleges in Cincinnati, Minneapolis, and New York. Students paid a $25 fee for a two-month program that allowed them to gain experience with volunteer customers.59 The Greater Richmond Barber College charged the same tuition rate, and an additional fee for room and board if needed.60 A 1908 barbers’ guide described the beginning of legislation as a concern for the public who might “stumble” into unsanitary shops managed by “incompetent” barbers who graduated from run-of-the-mill barber schools. The guide further compared law and medical schools to barber schools in an effort to draw a connection to the “proper” training needed for specialized professions.61 Since the union disdained barber colleges and the saturation of barbers in the market, it would have a hard time convincing the state that regulation made sense.

In 1897, Minnesota was the first state to pass a law regulating the practice of barbering. Minnesota's law was similar to those proposed by ten states who followed suit by 1902. The key section in the law was a three-member board of examiners to be appointed by the governor: one member recommended by the union, one “employing barber,” and one “practical barber.”62 That the JBIUA was allowed to recommend a member of the board of examiners became a highly contested issue in other states. The central component of the law required all barbers to go before the board to obtain a license. The JBIUA's involvement received greater scrutiny in states with a larger number of black barbers and significant black political influence. In 1900 Minnesota had 2,528 total barbers; 1,731 were native white, 517 were German, and 196 were black. Opponents in other states mounted stronger opposition against proposed barber bills.

Reports of pending licensing bills in northern state legislatures focused on the “sweeping power of regulation” held by the proposed registration board. The Philadelphia Tribune noted that under the proposed state law, “the board would have the power to revoke any certificate of registration and thus bar from barbering any person for conviction of crime; habitual drunkenness; having or imparting any contagious disease; for doing work in an unsanitary manner; or for gross incompetence, following a hearing on charges.”63 While stressing the importance of the legislation and denouncing opponents, Mack's Barbers’ Guide professed, “For if they do not [want legislation], why don't they rise up, out of that shiftless, unpretentious manner and oppose it in a body.”64 In Ohio, black barbers did just that.

On January 23, 1902, Representative Clarence Middleswart, Republican from Washington County, introduced House Bill 180 in the Ohio General Assembly “to establish a board of examiners for barbers and to regulate the occupation of a barber in this state, and to prevent the spreading of contagious disease.” No one contested the bill's public health provision. The power of the board of examiners, however, received opposition. George Myers, Ohio's prominent African American barber, believed the JBIUA agitated for this bill because it would have required barbers to take examinations before a review board—a board with the potential to discriminate against black barbers. The union's direct involvement with the bill—the secretary-treasurer of the JBIUA actually wrote the bill—gave Myers further cause for concern. The distrust of the union went beyond Myers's abhorrence of unions. Few black barbers belonged to the union, and those who did were treated with contempt. The “black barber bill,” as Myers called it, threatened barber shop owners by potentially reducing their labor supply of black journeymen. The average black journeyman barber, however, lacked political connections and had more at stake. The board would have the power to deny a license to applicants without “good moral character,” promulgate rules as “necessary,” and revoke a barber's license for not complying with such rules.65

Myers led the opposition by calling on his associates in Ohio's Republican political machine. By 1902, Myers had fully established himself a major businessman and political figure in African American life. He had helped organize black voters for the Republican tickets in federal elections. He had pushed the party bosses to consider African Americans for patronage positions. Most important, he stayed in the governor and president's ears about racial violence that had been picking up steam throughout the country. In the ten years since attending the state convention in 1892, he had cultivated a number of political networks that he now had to call on to protect his livelihood. But, since he was less than successful in placing a significant number of blacks in patronage positions, and since neither Governor Asa Bushnell nor President McKinley heeded his advice on addressing racial violence, it was unclear how far his state Republican associates would go to bat for him to oppose the barber bill.

Myers wrote letters to several senators and the governor to solicit their support as personal favors against House Bill 180. He structured his argument around discrimination and the debt the Republican Party “owed” black voters. If the bill became law, Myers argued, “it will be the means of driving every colored boss-barber in Ohio out of business.”66 He claimed the pending bill would mean “a reenactment of the Black-Laws of Ohio” by a Republican legislature “against its most faithful and loyal allies, the colored voter.”67 Myers was right: blacks held a balance of power in midwestern states such as Ohio, Illinois, and Indiana.68 And white leaders knew it. Joseph Benson Foraker, a prominent white Ohio Republican in the 1880s, recalled, “The Negro vote was so large that it was not only an important but an essential factor in our considerations. It would not be possible for the Republican party to carry the state if that vote should be arrayed against us.”69 Members in the General Assembly, too, understood the political climate. It helped that there was an African American, George W. Hayes, serving in the state House of Representatives. Ralph Tyler reported to Myers that he visited Hayes at “the House,” and Hayes had assured Tyler that he would see to it that the bill was delayed. According to Tyler, Hayes heard some fellow representatives say “that if the bill would hurt the colored voters they [Republican leaders] would not stand for it.”70 Hayes also complained that other barbers besides Myers had not shown enough public protest. To be sure the General Assembly understood the magnitude, Myers presented a petition signed by 105 black citizens, presumably barbers, of his county, Cuyahoga. House Bill 180 was defeated, 60 to 36.71 Proponents did not give up, but the arguments on both sides, and the results, played out just the same. Barbering regulation would not succeed until 1933, three years after Myers's death.72 Ohio was among the last remaining states to pass a barber licensing law.

Black barbers in Ohio blocked the law from passing because of the political influence of key black leaders such as George Myers and Representative H. T. Eubanks, from Cuyahoga County. They were also successful because of the position of the state's black population as a balance of power in electoral politics. Myers's political influence was unrivaled because of his past work with the political machine. But it was unlikely the black electorate would bolt from the party if they passed a barber licensing law. This legislation was certainly more pressing for Myers and other barbers than for the average black citizen. In essence, Myers persuasively made the case that he could sway the mood of black voters if this bill had passed. White barbers made little effort to rally black barbers in support of licensing legislation, perhaps because of their low numbers. Ultimately, black barbers dealt a blow to the licensing movement here not because of numbers, but because of their political connections.

The southern landscape was the complete opposite. Here, black barbers lacked political influence, but they outnumbered white barbers. Organizing black barbers proved more central in the union's southern strategy to lobby for licensing legislation. If southern black barbers questioned the union's motives in setting up locals, they grew more suspicious when the union proposed regulation. In 1906, Victor Kleabe of Austin, Texas, an active member of the union, acknowledged, “We have been told that some colored barbers think the law is for the purpose of driving them out of business. That is not the case. We are all alike in the eyes of the license law.”73 Yet, considering the racial politics in the early twentieth-century South, blacks had no reason to believe the license law would operate any differently from other laws administered by the state that left them few protections, for example, from lynching or the convict lease system.74 Southern organizers failed to make these connections. By 1939, Maryland and Virginia were the only two southern states that had not passed a law regulating barbering, a reality that local white barbers desperately wanted to change.75

Union organizers in Virginia believed that the more black barbers they brought into the union fold, the less trouble they would have securing the passage of a state licensing law. They saw varying degrees of success as they surveyed large and small cities. Organizers established black locals in Portsmouth in 1913 and Bristol in 1921.76 In Bristol and Newport News, blacks were the only barbers organized into a local. The largest white shops in Newport News were members of the white local in Norfolk. The three white and eleven black shops in Suffolk were not interested in joining the union. In Roanoke, all the white shops belonged to the union, but the black shops were not organized. Organizers faced this dilemma so often that they usually referred to it as the “white and colored half-and-half.” Unorganized black barbers of Norfolk posed a major threat to the white Local 771. In July 1917, organizers successfully established a black local in the city.77 C. F. Foley, general organizer, described Alexandria as the “best organized town in Virginia—100 percent organized, both white and colored, and harmony prevailing between both.” Norfolk and Richmond were two key cities for the union to create alliances with black barbers and state officials to lobby for regulation. While in Richmond, organizers often hit a wall in their efforts to establish a black local. One organizer ended his Virginia tour in Richmond and concluded, “Then came the color line, which is drawn very tightly in this city, the same as in all other southern cities. One will have nothing to do with the other.”78

Despite the union's limited success in small towns, its failure to organize black barbers in Virginia's major cities proved to be a critical stumbling block to convincing the legislature the state needed a law to regulate barbers. In 1924, Senator Howard Smith presented a barbering bill to the General Assembly, which passed the Senate and House Committee on Laws at the last session of the year. The proposal had some key political supporters, such as Harry F. Byrd, longtime state senator who was elected governor in November 1925.79 Byrd's support was curious considering his championing of limited government.80 Among the bill's provisions, it proposed that barbers be required to enroll in a six-month barbering course, work as an apprentice for eighteen months, and pass a physical examination before receiving a license to practice barbering in the state.81 It also called for the creation of a state board of examiners to oversee its provisions. Black barbers were undoubtedly concerned about its numerous requirements. The law would consolidate the power of determining one's entry into the field in the hands of a state board. This initial bill raised a few eyebrows, but it did not amount to a major issue. White and black barbers were undoubtedly steeped in the proposed legislation because they already had a contentious relationship and they were certainly aware of similar laws that had passed in other states. The bill was defeated in the House, which prompted white barbers to form the Virginia State Journeymen Barbers’ Association to further the passage of a barber bill. They focused on lobbying at the state capitol and trying to win over the chief opponents of the bill: black barbers.

With six years to regroup, the union targeted the 1930 state legislative session to mark the beginning of a long battle between white barbers, black barbers, and the state over public health, state regulation, and the modern barber shop. In 1929, white journeymen and master barbers met in a convention in Norfolk to discuss the best means of securing the passage of a license law at the 1930 session of the legislature. W. C. Creekmore of Norfolk, chairman of the legislative committee of the Virginia Federation of Labor, stressed the need for lobbyists at the state capitol. He urged delegates: “If a candidate for the legislature asks for our support, find out if he is in favor of the license law. If he isn't don't support him, but if he is give him your vote whether he be a Democrat, Republican, or Socialist.”82 H. B. Hubbard, secretary-treasurer of the Norfolk local, acknowledged the “large delegation of colored barbers from Richmond who were very instrumental in defeating our bill last time.” Hubbard left convinced that these black barbers at the Norfolk meeting saw the light of regulation: “We showed them where they were wrong, and they expressed their willingness to help us next year.”83 Hubbard's perceptions could not have been more misguided. In fact, on January 22, 1929, black barbers organized the Barbers’ Protective Association of Virginia (BPA) to oppose the legislation. Perhaps Hubbard and other organizers believed they could organize enough black barbers outside of Richmond to demonstrate to the state legislature that only black barbers in Richmond were concerned. Whatever their strategy, at the 1930 session of the state legislature, members of the Barbers’ Protective Association made their voices heard.

On January 20, 1930, well over two hundred spectators, including a delegation of eighteen black and thirty-five white barbers, packed the legislature. By several accounts, Benjamin W. Taylor, vice president of the Richmond chapter of the BPA, was the surprise of the day. He gave a passionate, patriotic, nativist appeal: “I was born, bred and expect to die in America. We are American citizens and I think, Mr. Chairman and gentlemen of the committee, that you are too board-minded [sic] to allow outsiders, some of whom can't even speak our tongue, to come in” and dictate the welfare of the state's residents.84 The “outsiders” Taylor had in mind were the German and Italian barbers who organized for the union. He strategically made this an issue between American citizens and immigrants, as opposed to one between whites and blacks, to sway white legislators to concentrate on nation rather than race.

Taylor also thought it was odd the union advocated for this bill as a health measure, especially since Dr. Ession G. Williams, state commissioner of health, opposed it. Williams argued it was simply unnecessary for the state's health.85 Senator J. Belmont Woodson, physician and superintendent of the Piedmont Sanatorium, vocally opposed the bill, telling the Senate it was a poor excuse for a “health measure” and was an “insult to the intelligence of the Legislature of Virginia.” The Senate killed the bill, but a substitute was offered. It eliminated the examining powers of the board and left physical examinations to the Board of Health, which would only give the barber board licensing powers. Weeks after the original bill was defeated, fifty delegates from across the state attended a BPA convention to oppose the bill's new incarnation.86 Black barbers simply distrusted the union and the white barber's association because they did not accept blacks as equal members. Therefore, blacks were left with no other reasoning than to believe that the motive behind regulation was to “eliminate…from the field of competition the Negro barber who serves white trade.”87 Health officials, members of the Senate, such as Woodson and others, and both city newspapers echoed these concerns of race and exclusion.

Not only did the barber bill occupy a major portion of the General Assembly's agenda, it also filled the pages of the Richmond News Leader and the Richmond Times-Dispatch for thirty years. Both papers opposed the bill and identified its racial motivations. White journalist Virginius Dabney was a vocal critic of the licensing measure in the Times-Dispatch. Virginians were well aware of the issues, but Dabney reached out to a wider readership. In July 1930, his article in the Nation, a liberal journal, placed the bill in a larger national and racial context. First, Dabney equated the union's efforts to regulate Virginia barbers with their successful efforts to pass legislation in most states west of the Mississippi, and the beginnings of this movement in the South. He attributed the unions’ difficulties in the South to “the large Negro population and the widespread belief that barber bills below the Potomac are designed to eliminate Negroes from the trade.” Although he indicated that only four southern states had passed licensing laws, in fact eight southern states had such laws on the books.88

Most strikingly, Dabney broadened the discussion of the proposed barber board to draw similarities to racial bias in other state administrative bodies. Opponents of the board believed a white-dominated board with the power to decide who would be granted a license would effectively spell the end of black barbers servicing a white market. Dabney suggested the board might exercise this discriminatory power through the kinds of questions they posed on the examination. He shared sample questions that were published in the Square Deal in 1929. “Here are some of the questions,” he wrote. “How many hairs are there to the square inch on the average scalp? Where is the arrector pili muscle located and what is its function? How is a hair connected with the blood stream and nerve system? Describe the function and location of the sebaceous glands. What is the scientific name for hair which shows a tendency to split…imagine the glorious opportunity which such questions afford a board of white barbers who wish to eliminate troublesome Negro competition.”89 Without explicitly referencing it, Dabney conjured images of disenfranchisement and the administration of the literacy tests in southern states. Southern state voter registration boards required citizens to read passages from various state or federal documents and answer questions related to government. They asked blacks more difficult and obscure questions, however, and sometimes flat-out said they did not read a passage correctly when they had done so. In the end, these boards rejected many literate blacks and registered illiterate whites.90 From the beginning, the white press consistently placed race at the center of their discourse on the battle over the bill.91 Dabney had written critically on the bill in the Richmond Times-Dispatch since 1930, and continued to do so after he became editor in 1936. He also published articles denouncing the poll tax and urging the passage of a federal anti-lynching law.92 For Dabney, and most important for the scores of black barbers who had been denied the franchise, the proposed barber board reeked of this “race-neutral” entity and examination policy that would essentially be implemented along racial lines.

The JBIUA had to contend not only with black barbers, but also with white Virginians who viewed proposed legislation as a threat to their southern way of life. The public discourse reflected whites’ competing ideas of the modern barber shop. In a letter to the Times-Dispatch in 1932, Dan O'Flaherty, a white Richmond citizen, charged the JBIUA with attempting to displace “pleasant” and “efficient” black barbers whose “equipment is as good and as sanitary as any.” O'Flaherty opposed the call for whites to displace blacks in barbering because he believed whites could not be as cheerful and pleasing when serving the white South. “We in Virginia,” he asserted, “know that the colored man is the best servitor in the world…. He is furthermore an integral part of the courteous background of Virginia life. The colored barber who waits on white men is invariably a higher type of citizen of his own race than the white barber is of his race. Many Richmond colored barbers were brought up with and by our good families.”93 O'Flaherty emphasized the importance of black personal service work to southern traditionalism. He spoke for many southern white men who bound blackness and cheerful service as a well-managed racial order. They perceived this as a society where black service workers accepted an inferior position in the public and private sphere.

O'Flaherty's nostalgia for a servile black citizenship reflected larger southern attitudes toward black service workers. In 1926, the white barber's union convinced the Atlanta city council that black barbers should be prohibited from serving white patrons. Many council members thought it was yet another segregation measure, gave it little thought, and passed it. Not long after the council passed the ordinance, it received a flood of protests from white citizens asking the council to reconsider or the mayor to veto it. Civic, religious, and business organizations wrote letters to the mayor and a supportive Atlanta Constitution editorial board. White opponents based their protests on three arguments. First, this ordinance was a ploy from white barbers to get around black competition for white patrons. Second, and most startling, the ordinance was an unjust affront on American democracy. They applauded barbers’ work ethic and applauded themselves for “protecting” black citizenship.94 The Constitution went so far as to claim, “Georgia shows as much justice and as much fairness to the negro as any state in the union—and a great deal more than some.”95 As ridiculous as this may sound—given the Atlanta race riot twenty years earlier, disfranchisement, and segregation in public accommodations, just to name a few areas in Jim Crow's reach—these white citizens truly believed they were fair to black citizens because they believed they were deeply connected to their black servants, which for them included barbers.

Hence, the third argument got to the heart of white southerners’ protests; messing with black barbers meant messing with black service workers, and southern tradition. If black barbers could be prohibited from grooming white patrons, whites questioned, feared even, what would prevent the state from telling them “who shall occupy our kitchens, drive our automobiles, wait on our tables, and nurse our children?” An Atlanta resident wrote to the Constitution praising its support of black barbers. “I have had a colored barber since I was old enough to receive that service,” he fondly remembered, “and am old-fashioned enough to want to continue it, nor do I believe the good citizens will consent to any such unfair discrimination.”96 M. Ashby Jones, a moderate white pastor who worked for interracial cooperation, put the matter succinctly in his article titled “The Negro Barber Shop and Southern Tradition.” He too went down memory lane, recalling a time when he “sat on the high stool” as a youngster “while the kindly voice of old Jim, the barber, told me folk-stories,” and at the University of Virginia, where “Bob” was the “wise adviser of every student,” and in later years, “Phil…who counted his friends in the old capital of the Confederacy by the scores and hundreds.” “These are not mere personal memories,” he proclaimed. “They are the memories of the south” (emphasis added). By declaring black barber shops a southern institution, he made a grand gesture to a tradition of black subservience, which, he reminded readers, “we have inherited from our past.”97 If slavery could no longer exist—southerners lost that battle—then they would fight hard to hold onto the vestiges of the Old South. Whites clung to black domestic servants, or their old mammys, in similar ways.98 For many whites who rendered their protest in public forums, this would not be a Lost Cause. The council did reconsider by offering a public hearing, out of which came a “compromise.” Under the revised bill, black barbers would be prohibited from serving only white women and children under fourteen. The Atlanta Chamber of Commerce pressed on and was successful in getting an injunction. Finally, in September 1927, the Fulton County superior court declared the ordinance unconstitutional.99 For their twisted support of black barbers who groomed white patrons, a writer for the Chicago Defender said it well that this episode illustrated “the truth that the ‘d’ in Dixie will always stand for dirt.”100 While Virginia's approach to licensing was not as directly race-based as Atlanta's plan, the underlying message and meanings of black service work to the South were quite similar.

W. C. Birthright, general secretary-treasurer of the JBIUA, wrote a letter of response to the Richmond Times-Dispatch editor to deny O'Flaherty's charges that the licensing law was intended to discriminate against black barbers. Birthright proclaimed, “In our desire for better barbers, white or colored, in this modern age, we are convinced that the barber must know something of a human body on which he operates. The barber business is a science when the interest is shifted to the proper study of his work” (emphasis added). Birthright's notion that the barber “operates” on a human body was consistent with union reformers’ nostalgia for the “professional” days of the old barber-surgeon. “It affects white and colored barbers alike,” he continued, “and legislates no one out of business, as charged, but requires the future barber to be better prepared for the service he will render, and the present barber to conduct a scientific barber shop and to fit himself physically so he will not transmit disease to patrons.”101 Birthright's response reflected the union's vision of modernity, which emphasized the advanced, scientific skill of new professional barbers and the need to protect public health. Despite his claims of racial neutrality, Works Progress Administration workers in the 1930s acknowledged that the bill “has thus far been successfully warded off, due in no small part to the favor with which white Virginians regard Negro barbers and also to the efforts of the Barbers’ Protective Association.”102

Although the state legislature did not pass a licensing law in the 1930s, proponents maintained a dual state and city strategy. Where statewide strategies failed, reformers were successful on the local level. Norfolk (1932) and Richmond (1935) passed city ordinances to regulate barbers. It required every person applying for a certificate of registration to include a statement from a licensed physician “declaring that he is free from any contagious, infectious or communicable disease.” The ordinance also required that barber shops be inspected on a regular basis to ensure proper sanitary condition.103 The Department of Public Health required barbers to take the Wassermann test before they could apply for a license. August von Wassermann and Albert Neisser, at the Robert Koch Institute for Infectious Diseases, developed the Wasserman test in 1906 as a diagnostic blood test for syphilis. Richmond's ordinance included a similar public health component requiring regular sanitation inspections, but a physical examination requirement, “to prevent the spread of syphilis,” did not pass.104

The Sanitation Division in the Department of Public Health assumed responsibilities for enforcing the new law, which disproportionately affected black barbers. When Joseph A. Panella, second-generation Italian and secretary of Local 771, was appointed Norfolk's inspector, he assured barbers it “makes no discrimination as between races, and will give a certificate of registration to any barber now in practice who is physically fit.”105 Black barbers were surely concerned with ambiguous language in the ordinance such as “physically fit.” Panella noted in his second annual report that forty-four black barbers and thirteen white barbers tested positive for syphilis. In the first year of Norfolk's ordinance, thirty-nine barber shops were closed, while nine were closed in the second year.106 According to Richmond's chief city sanitary officer Arthur B. Ferguson's annual report in 1936, inspectors made 3,207 visits and cited operators for combs, razors, mugs, and windows.107 The following year, inspections reached a racial fever pitch in the city. The Sanitation Division directly targeted black barber shops for inspection to enforce the ordinance, such as requiring hot and cold running water in their shops. Inspectors ordered twelve black barbers to comply with the city sanitary code by making various upgrades or improvements to their shops. For example, an inspector ordered Richard Howard, at 552 Brook Avenue, to install a new water heater or receive a $25 fine each day the alleged violations persisted. Unfortunately, Howard's newly installed heater exploded, causing injuries to himself, his shop, and a customer. While there is no evidence indicating the condition of Howard's water heater, it is ironic that this incident occurred as a result of Howard complying with the city. K. C. Sargeant, one of the three inspectors who conducted the investigations, testified that black barbers heated water on a stove or grill. Sargeant acknowledged, “There are about seventy-five Negro barber shops and beauty parlors in Richmond and we are rigidly inspecting all of them.” Yet, Ferguson insisted, “there is absolutely no discrimination being made against the Negro barber in our effort to enforce the code.”108

Despite the vigorous city inspections, Richmond's white barbers were not satisfied without a physical examination provision, which the City Council approved in August 1939.109 The new ordinance required barbers to prove they were free of any infectious diseases, particularly venereal diseases and tuberculosis.110 There were approximately 207 barber shops (122 white, 85 black) and 585 barbers (313 white, 272 black) in the city. When the Ordinance Committee specifically asked Roscoe B. Greenway, legislative chairman of the Central Trades and Labor Council, what black barbers thought of the new requirement, he said they had been “informed and acquiesced to its passage.”111 Within the first five months, inspectors “uncovered” eighty-nine cases of venereal disease and five cases of tuberculosis among barbers, beauticians, and manicurists. The venereal disease cases amounted to 5.5 percent of the total of the three groups.112

Whites’ obsession with containing contagious diseases through occupational laws encouraged some in the medical community to better inform the public. On October 31, 1939, Dr. Joseph E. Moore of Johns Hopkins University delivered a speech at the New England Post Graduate Assembly of Harvard University to address the misconceptions of syphilis and communicable diseases. According to Moore, the examination of barbers, beauticians, domestics, cooks, and waiters to determine if they had syphilis was unjustified because “ninety-nine and nine-tenths per cent of all infections with syphilis are acquired by means of one or another form of sexual contact and by this means only.” Education awareness campaigns tended to target African Americans. White employers and state agencies used these campaigns to “exercise their prejudice against Negroes,” forcing them out of work.113 Although Norfolk inspectors found that forty-four black barbers tested positive in 1935, ultimately there was no danger of them passing the disease to their customers. As historian Pippa Holloway points out, Virginia's venereal disease program in the 1930s demonstrated how whites attempted to employ the state and public policy to regulate sex and manage race and class relations.114 In whites’ attempts to regulate the barber shop by policing the space for sexually transmitted disease, black women were indirectly implicated in this “public health” project. The barber bill forced many to wonder who needed to be protected and from whom. No one, not even Dr. Moore, dared ask what kind of sexual activity would be happening inside barber shops that the public needed protection from any sexually transmitted diseases. Questions of sex did not enter the public discourse on the bill, but even the general concern of public health did not go without question and critique.

White barbers’ success on the city level encouraged them to keep pushing for a state law. And, they pushed for three solid decades. The bill was introduced and rejected so much the press called it the “customary barber bill.”115 Senator Alexander Bivins, a supporter of the legislation, made it known that he patronized a black barber shop and would continue to do so if the bill passed. Opponents, barbers and senators alike, identified the bill's hidden, and potentially far-reaching, agenda. In 1938, Senator Gordon B. Ambler pointed out the irony that the state board of health opposed a bill that proponents claimed was a health measure. He was not critiquing the health board, but rather was skeptical of the bill. He charged the union with introducing this legislation to displace black barbers and increase prices. “In some sections of Virginia,” he noted, “Negro barbers have charged 25 cents for haircuts and their shops have been picketed by labor to force them to raise the price. We are faced with one thing in this country—protection of our democratic institutions.”116 White barbers were far more concerned with employing the state to help them protect their jobs, even beyond the competition with black barbers. For example, after Richmond passed its 1939 ordinance, white barbers took issue with city firemen who occasionally gave free haircuts to children. John Lloyd filed a complaint with the city, noting that this practice “placed them under the provisions of the barber ordinance.”117 Who knows what Lloyd would have thought of a father cutting his son's hair at home, but this surveillance informed the underlying protectionist motives of regulation.