CHAPTER 4

Rise of the New Negro Barber

IN 1904, Paul Laurence Dunbar published The Heart of Happy Hollow, a collection of short stories that included “The Scapegoat,” the first in a long line of twentieth-century works of fiction by black writers to explore the role black barbers and barber shops played in black communities. In the story, Dunbar captures well the changing currency of barber shops in the black community. Robinson Asbury, the protagonist, starts out working as a bootblack in a barber shop and moves up the ladder to become a porter, messenger, and barber, eventually purchasing his own shop. Dunbar was conscious of the racial politics surrounding color-line barbers who did business downtown to serve the white elite and the protest against these shops. Asbury opens his shop where “it would do the most good,” which was in the town's black community as opposed to downtown. In locating Asbury's shop within the black community, Dunbar provides a keen contrast to the color-line shops of old. The narrator explains:

The shop really became a sort of club, and, on Saturday nights especially, was the gathering place of the men of the whole Negro quarter. He kept the illustrated and race journals there, and those who cared neither to talk nor listen to some one else might see pictured the doings of high society in very short skirts or read in the Negro papers how Miss Boston had entertained Miss Blueford to tea on such and such an afternoon. Also, he kept the policy returns [numbers gambling], which was wise, if not moral.1

The shop's success establishes Asbury as an influential member of the black community; he comes into contact and establishes relationships with a number of prominent men and has access to the latest news and information. For these reasons, the local white political machine selects Asbury to manage the black constituency. He will “carry his people's vote in his vest pocket,” and party managers will give him money, power, privilege, and patronage. Asbury is catapulted to a leadership position not simply because he was a barber, but because his barber shop was a gathering place for black men and potential voters. Although Asbury is fictional, men like him and shops like his became important fixtures in black communities throughout the twentieth century.

In addition to increasing competition, professionalization, and regulation, black barber shops also underwent dramatic internal changes between 1900 and 1940. The typical black shop in 1900 included three to four black barbers shaving white patrons, while a set of other white men sat in the waiting chairs talking or reading the newspaper. Those patrons were likely middle- to upper-class men who preferred to be groomed by a black barber to reinforce their own racial and class identities. Deference organized the barber-patron relationship that barbers had to negotiate to maintain trust. Trust in this case meant that white patrons did not think their black barber was capable of slicing their throats or serving black patrons when the shop closed. The black barber-white patron relationship of the nineteenth century was impersonal, paternal, and based on patron-clientage; in short, these were business relationships. By 1940, these businesses that capitalized on a white clientele had been transformed into black commercial public spaces. Now, black barbers openly trimmed the locks of black men. Black shop owners no longer stood among the wealthiest members of black communities, but barber shops and beauty shops nevertheless led the list of successful black businesses in most cities. In the process, barbers’ social standing changed and became tied to their customer base in the same way that a preacher was significant primarily because of his congregation. For black customers, the regularity of shaving-time, or more accurately haircutting-time, allowed a relationship to develop that was akin to the doctor-patient trust. This relationship was personal and often generational, as a barber might groom multiple generations of men and boys in one family. By the mid-twentieth century, conversation and congregation were hallmarks of most black barber shops.

This most dramatic of transformations in the first four decades of the twentieth century reflected not just white barbers’ efforts to realize their visions of a modern, professional barber shop, but also black barbers’ historical experiences. Black barber shops were products of both the rise of Jim Crow and Progressive-era labor reform, as well as blacks’ increasing support of the concept of black autonomy. Crystallized during the first large-scale black migration, the concept of autonomy within the black barber shop was both an institutional principle and an ideological orientation of race and masculinity. Color-line barbers’ shift in location and customer base was not solely a product of displacement. Rather, a new generation of African American businessmen—the first to be born after the Civil War—put less emphasis on catering to the white elite and paid more attention to the black urban market. This new generation of black barbers recognized that they had more options than adhering to the color line in their shops. Instead, blackness and black culture could be produced and reproduced in a commercial space that brought black men of various class levels to the same shop. Work and leisure defined the boundaries of the making of the modern black barber shop, which allowed entrepreneurship, black identity, and public discourse to flourish.

Black Barbers for Black Clients

This new generation of barbers had been born into freedom between 1870 and 1880 and entered the field during the rise of Jim Crow and increasing competition between white and black barbers. The era was marked not only by increasing segregation and racial violence, but also by a rising tide of black resistance and protest.2 Unlike their predecessors, these new barbers were not committed to white customers. Instead, they catered to a small but growing black consumer market. Like other black entrepreneurs, political leaders, and social reformers of the era, this generation of “New Negro” barbers began to focus on the internal needs and wants of black communities, in the process becoming significant fixtures in those communities.

The turn of the century was a transitional period in barbering, and color-line barbers of the old generation still had significant influence as New Negro barbers established themselves. As businessmen, both generations believed African Americans should control their own economic freedom. Color-line barbers like George Myers agreed with the general economic philosophy of Booker T. Washington that business and economic development was the best path to racial advancement. Myers believed African Americans would have to make money to rise above their subjugated status.3 At a 1905 banquet for Washington in Cleveland, Myers proclaimed, “For a Negro to go into business means a great deal. It is indeed a step in social progress.”4 It was a masculine presumption that individual economic progress would stimulate collective racial advancement. Barbers of all ages would have agreed with Myers, but economic self-sufficiency has been used as a conservative and radical philosophy within black political thought.

The old and new generations disagreed, however, on the role that race should play in business marketing and promotion. The emphasis on appealing to black consumers and creating a separate economic sphere ran counter to the business philosophies of color-line barbers of the old generation. Since establishing the National Negro Business League (NNBL) in 1900, Washington extended numerous invitations to Myers to speak on the barbering profession at the League's annual conventions, but Myers declined every time.5 These national conventions provided a forum for African Americans from across the country to report, or more often boast, of the business activity taking place in their cities and sound the call for mutual cooperation between black entrepreneurs and consumers.6 Myers, however, urged black entrepreneurs to appeal to both black and white customers without racial distinctions. “Many of our people in business and practicing the professions seek to make color an asset,” he stated. “Don't be a colored business man. Don't be a colored professional man. It's an admission of inferiority.”7 Myers was one of Washington's most loyal allies in the North, even though he fundamentally disagreed with Washington's philosophies. The racial politics of barbering prevented Myers and barbers like him from appealing to white and black customers, but a younger generation of barbers viewed a black market differently.

By 1915, the black elite occupational structure shifted from personal service entrepreneurs to professional endeavors and financial services entrepreneurs. Black doctors, lawyers, and teachers began their ascent to racial leadership. Financial services entrepreneurs—such as accountants, realtors, and insurance agents—defined the new black business community of the twentieth century.8 These professions may have been more prestigious, but they also required significant start-up costs. The new generation of barbers would not achieve the same wealth as Myers, Alonzo Herndon of Atlanta, or John Merrick of Durham, but a haircut would always be in demand, and the costs to enter the field would remain low. Even though barbers faded out of the black elite occupational structure, shop owners were still a part of the business class.

Barbers were among a group of businessmen and -women who stood apart from the new black business and professional class. Unlike black grocers or tailors, black barbers, beauticians, and undertakers did not compete with their white counterparts, who generally did not want to handle black bodies. Moreover, black customers made conscious decisions to patronize black barber shops. Black consumers may have questioned whether white-owned grocery store chains stocked a better quality of breads at a lower price than local black grocers did. Black patients may have questioned if black physicians were as qualified to treat them as white physicians. But, black men seldom questioned whether white barbers provided a better haircut or closer shave. Additionally, black consumers could neither congregate in a white barber shop nor discuss racial matters in the company of white patrons. African Americans needed spaces where they could not only get a haircut but also gather in public, without the usual surveillance that accompanied other public spaces like parks, groceries, and street corners, to make sense of the changing social, economic, and political landscape around them. Since barbers did not have to compete with white businesses in the same ways as their peers, the masses of black men who migrated to southern and northern cities during the Great Migration increased their consumer base many-fold.

The Great Migration marked a central turning point in the growth of black barber shops, and it was during this era that they first began functioning as black public spaces. During the first four decades of the twentieth century, black barbers welcomed thousands of new black consumers as a result of Jim Crow repression in southern rural areas and labor shortages in northern cities. Robert Horton, a shop owner in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, spent a week with his daughter in New Orleans while she was enrolled at Straight College. During his brief stay, he cut hair in a shop and became engrossed in the constant talk about the migration. One day a labor agent came in to convince people to go north to fill labor shortages.9 According to historian James Grossman, Horton had “occasionally received letters from a brother who had moved to Chicago in 1898,”10 so while this was not news to him, he sensed a tide was turning.

Like Horton, many African Americans sought information from others as they weighed the possibilities of such a move, and many turned to the Chicago Defender as an authoritative source in describing job opportunities and living conditions in the city. Indeed, the Defender was sold, or at least available to read, inside barber shops “to supply topics for barber-shop discussion.” Many readers also wrote to the paper, asking about housing and job opportunities. While most of these inquirers sought industrial jobs, barbers also wondered what the “Promised Land” held for them. “I am a barber of 20 years experience,” a barber from Starkville, Mississippi, wrote to the Defender. “I am now in the business for white but I can barber for white or color[e]d…. Also I am a preacher…. I would like for my children to have the advantage of good schools and churches.” Black churches, especially in rural areas, could not afford to pay their preachers substantial salaries. Therefore, preachers usually worked jobs that gave them considerable income and flexibility, like barbering, to carry on their pastoral duties.11 A barber's wife from Greenwood, Mississippi, also wrote to the Defender for the sake of her children; she was concerned, like her husband, that businessmen would not fare as well as laborers.12 Although these barbers appear to have been migrating for better educational opportunities, they lacked confidence that they would find jobs in a barber shop up north. These kinds of letters from barbers were rare, but they reveal the uncertainties of transferring their skills to a new region.

The Defender could have promised both Mississippi barbers that the scores of other black migrants to the North would certainly need haircuts. Robert Horton saw these business opportunities. When he returned home to Hattiesburg, he sold his shop and convinced his customers to migrate to Chicago with him, his wife, and children. In 1917, he had secured a group discount on the Illinois Central Railroad for him and his party. If blacks were going to move north, Horton wanted to capitalize on their grooming needs. It is also possible that his own customers had been debating whether or not to go north, and Horton simply did not want to be left behind. He earned on average $25 per week, his wife did not work, they had two children, and they owned their home. Horton believed he could substantially improve his business and his family's well-being.13

Between 1910 and 1930, approximately 1.5 million rural migrants settled in southern and northern cities, and as they did so they were forced to live in segregated neighborhoods.14 Moreover, as property values increased and white business owners competed for prime real estate in central business districts, black businesses, including barber shops, were forced to relocate to segregated districts. Black urban migration and institutional racism thus contributed to the development of black business districts in American cities.15 Black business districts were centers of black commerce and recreation where barbers could position themselves close to black consumers. Because of their concentration and size as well as wartime labor demands and the higher wages their residents commanded in the factories, black communities in these large cities were better able to support black-owned businesses.16 Before the World War I–era migration, black business districts were located adjacent to central business districts along a particular street: Auburn Avenue in Atlanta, Parrish Street in Durham, Greenwood Avenue in Tulsa, and Beale Street in Memphis. During and after the migration, business districts developed along major streets within black neighborhoods.

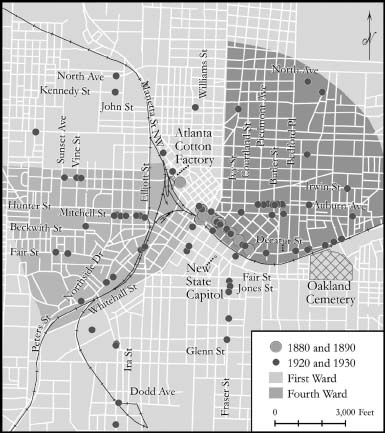

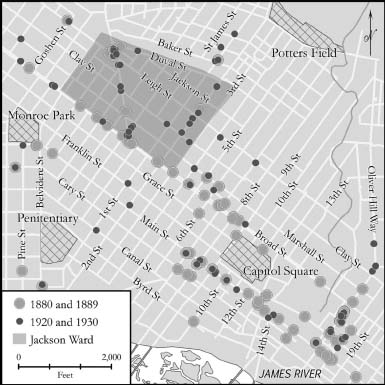

City directories show a shift in where black barber shops were located: from downtown city centers in the 1880s to emerging black pockets (wards or blocks) by the 1920s. In most cases, the movement of barber shops reflected the residential patterns of black residents, which varied by region and city. African American migrants in the urban South settled in several neighborhoods, but were confined to particular city blocks. Between 1880 and 1890, the black-owned shops listed in the Atlanta and Richmond city directories were mostly located downtown, in Atlanta's Five Point area and on Broad Street and Main Street moving away from the Capitol Square in Richmond. In both cities, black barbers had been opening shops outside of downtown by the 1920s. Black businesses in Atlanta were forced out of the central business district as a result of the race riot of 1906 and the efforts of the city council to restrict black businessmen and -women from leasing downtown commercial space. Consequently, they established an adjacent black business district on Auburn Avenue (formerly named Wheat Street). The “Old Fourth Ward” on the East Side supported the development of Auburn. This street became the center of black consumer activity as businesses that served white patrons now primarily served the black community. In 1913, the city council enacted a zoning ordinance to legalize residential segregation, which resulted in the black community expanding to the west of the central business district to the West Side near Atlanta University Center.17 Two years earlier Richmond's city council passed a similar racial zoning ordinance that designated black and white neighborhoods.18 By 1920, black barber shops were moving with their new customer base. Particularly, many barbers in Atlanta opened their doors along Auburn, where Alonzo Herndon headquartered Atlanta Mutual and Henry Rucker (former barber and politician) opened his Rucker Building, which provided office spaces. Strikingly, many of these barber shops were just doors from each other. In 1930, seven African Americans owned shops very close to each other on Auburn (at 223, 231, 240, 250, 270, 280, and 291). This kind of clustering did not happen along Second Street in Richmond, the center of black commercial activity in Jackson Ward; rather, shops were more dispersed throughout the ward. While the number of black shops declined on major downtown streets in these two cities, a large number of blacks remained downtown to groom white men, a practice that continued through the 1960s.

Figure 10. Black barber shops in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1880, 1890, 1920, and 1930. Cartography by Boundary Cartography. Source: Sholes’ Directory of the City of Atlanta for 1880 (Atlanta: A. E. Sholes, 1880); Atlanta City Directory for 1890 (Atlanta: R. L. Polk and Co., 1890); Atlanta City Directory, 1920 (Atlanta: Atlanta City Directory Company, 1920); Atlanta City Directory, 1930 (Atlanta: Atlanta City Directory Company, 1930).

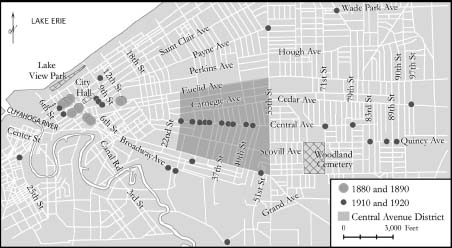

The urban North showed similar movement relationships between black shops and migrants, and patterns away from downtown city centers. These cities absorbed the lion's share of southern migrants. By 1920, nearly 40 percent of African Americans in the North resided in eight cities, which included Chicago, Cleveland, New York, and Philadelphia.19 Southern migrants initially settled in neighborhoods where family and friends were located. Denied opportunities to live in other areas, they had little choice. Black migrants to Cleveland settled in the central area of the city, from Euclid to Woodland and 81st to 105th Streets; however, black barber shops made a slower eastward movement from downtown to this area, which was east of 55th Street (formerly named Wilson Street).20 The shops in 1880 and 1890 were concentrated downtown, but by 1910 began moving east along Central Avenue. The black barbers, such as George Myers, who were still downtown in 1910 or 1920 had likely been there since the 1890s.

Figure 11. Black barber shops in Richmond, Virginia, in 1880, 1889, 1920, and 1930. Cartography by Boundary Cartography. Source: Chataigne's Richmond City Directory for the Years 1880-'81 (Richmond: J. H. Chataigne, 1880); Chataigne's Directory of Richmond, VA., 1889 (Richmond: J. H. Chataigne, 1889); Hill Directory Co.'s Richmond City Directory, 1920 (Richmond: Hill Directory Co., 1920); Hill's Richmond, Virginia, City Directory, 1930 (Richmond: Hill Directory Co., 1930).

Figure 12. Black barber shops in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1880, 1890, 1910, and 1920. Cartography by Boundary Cartography. Source: The Cleveland Directory for the Year Ending June, 1881 (Cleveland: Cleveland Directory Company, 1880); The Cleveland Directory for the Year Ending July 1891 (Cleveland: Cleveland Directory Co., 1890); The Classified Business and Director's Directory of Cleveland, Ohio, 1910 (Cleveland: Whitworth Brothers Co., 1910); Cleveland Directory for the Year Ending 1921 (Cleveland: Cleveland Directory Co., 1920).

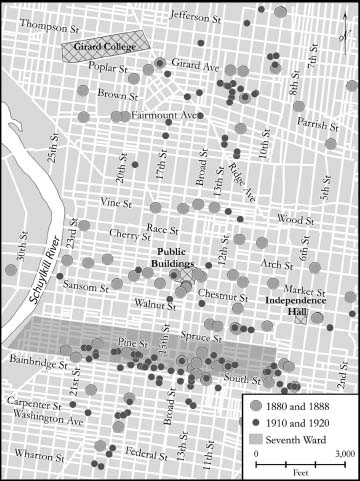

Unlike in Cleveland, shop movement in Philadelphia was less unidirectional. As residents, blacks were evenly distributed in the south, north, and west sections of the city.21 While many barbers opened shops in each of these sections between 1870 and 1920, a majority of them located their shops south of Market Street. Most revealing is that there were very few black-owned shops near Market between the Schuylkill River and Independence Square after 1900. By 1910, many of these shops were located in North Philadelphia and farther south, in the western section (west of Broad Street) of the seventh ward.22 The seventh ward was a major area populated by predominately black residents and businesses. This was the famed district that W. E. B. Du Bois researched for his 1899 book The Philadelphia Negro. Yet, by 1920, those shops continued to move farther south of South Street, outside of the ward boundaries.

When black men migrated to southern and northern cities, they searched for housing, work, a place to worship, and a place to get a haircut. Recent migrants either randomly visited shops in their neighborhoods or visited shops recommended by family or friends. After Horton arrived in Chicago, for example, he opened the Hattiesburg Barber Shop on 35th Street near Rhodes, which was just a few blocks west of the black commercial activity on “The Stroll” on State Street. In fact, of the fifty barber shops listed in the 1915–1916 Colored People's Guide Book for Chicago, thirty were located along State Street between 15th and 55th, but most were near 35th. Horton likely wanted to distance his shop from the bottleneck on State Street. Horton's shop became a gathering place for migrants from Hattiesburg and surrounding areas to collect their cultural bearings as they adjusted to city life, and a contact point for blacks in Hattiesburg still considering the move.23 As a prominent figure who left Hattiesburg, Horton “became the recipient of numerous letters of inquiry about conditions in Chicago.”24 At the barber shop, people could connect with other southern migrants and longtime residents to gather information on city life and politics, such as employment, and black community life, such as night life and schools. Barbers did not need to look for customers; customers found the barber shop. Color-line barbers placed far more advertisements in white newspapers in search of white customers than barbers placed in black newspapers looking for black customers. Word of mouth was less expensive, and more effective, in a Jim Crow setting.

Figure 13. Black barber shops in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1880, 1888, 1910, and 1920. Cartography by Boundary Cartography. Source: Gopsill's Philadelphia City Directory for 1880 (Philadelphia: James Gopsill, 1880); Gopsill's Philadelphia City Directory for 1888 (Philadelphia: James Gopsill, 1888); Boyd's Philadelphia City Directory, 1910 (Philadelphia: C. E. Howe Co., 1910); Boyd's Philadelphia City Directory, 1920 (Philadelphia: C. E. Howe Co., 1920).

As a new black business and professional class emerged, they saw their livelihoods tied to a growing working-class population.25 Black financial institutions (such as banks, insurance companies, and building and loan associations) and black fraternal and societal associations anchored black business districts. They not only provided financial stability to these districts through loans and real estate holdings, but they also provided spaces for black residents to hold meetings, organize social gatherings, and congregate. However, there were usually more barber and beauty shops located in black business districts than any other business, and they regularly accommodated the working and middle classes. For example, in Chicago in 1938, the twelve black barber shops and eleven black beauty parlors led the field in number of businesses on 47th Street.26 Barber shops located in black business districts benefited from the foot traffic of black shoppers and workers on lunch breaks. African Americans could visit the barber shop before or after they attended to other business or recreation in the district. For Charles Herndon and Julia Lucas, black tobacco workers from the American Tobacco Company and Liggett and Myers were a large segment of their customer base in their barber shop on 121 Mangum Street near downtown Durham.27 Yet, black consumers could accommodate only a small fraction of the total number of black barber shops in a given city, which means most shops were dispersed throughout black neighborhoods.

As black barber shops increasingly welcomed a black clientele, black women had begun to establish their leadership in an emerging beauty industry. The rise of the beauty culture industry paralleled this population shift and the inward focus of black business culture. In the early twentieth century, Annie Turnbo-Malone, Madam C. J. Walker, Anthony Overton, and Sarah Washington produced hair preparation and cosmetic products for black women. Turnbo-Malone and Walker did more than create and sell products—they were instrumental in creating an industry to sell a system that included hygienic and hair care products, employment, opportunities to open salons, and philanthropic and political engagement with black communities.28 The industry developed based on commodity products, which provided black women the capital and opportunity to establish beauty shops as permanent spaces to facilitate their work as beauty culturists. While women found new opportunities in the beauty industry, they also found opportunities in the barber shop.

Women knew that they could use these shops, instead of or along with beauty shops, to their advantage in various ways. Black women worked in barber shops more often as manicurists partly because there was less competition for male customers. Color-line shops provided this service to their white customers, and Zora Neale Hurston provided rich detail of her work in Washington, D.C. But, black men also placed their hands across the table for their nails to be buffed and filed. Before Bessie Coleman embarked on an amazing career as a pilot, she worked as a manicurist in at least two barber shops in Chicago's Bronzeville neighborhood. One of her biographers asserted that her male customers “appreciated her looks and charm,” but at least one customer looked beyond her appearance. While working at the White Sox Barber Shop, her brother, a World War I veteran, sat in the shop talking about how French women could fly airplanes. Coleman was intrigued, and received considerable encouragement in her interest from a regular customer, Robert Abbott, founder of the Chicago Defender. With Abbott's encouragement and her savings, she attended aviation school in France, which was the catalyst for her groundbreaking contributions as a pilot.29 Coleman used her position as a manicurist to her benefit. This is not to suggest that she became the first black female pilot because she worked with and around men, but she did take advantage of her networks.

Most male customers did not help manicurists secure other employments; in fact, most were simply titillated by their mere presence. Black newspapers often facilitated a masculine voyeuristic culture surrounding black female barber shop workers. A short notice in the Defender extolled, “An added feature of Holland's tonsorial parlor, 15 West 51st street, is a dainty manicurist—and oh, boy, she sure can hold your hands. Well, I know they've bought some more chairs for the boys.”30 The paper reduced this manicurist to a “dainty” “feature,” or some object that black men in Chicago's Black Belt should observe. “Yes, we have a Manicurist,” Ernest Joyner of Pittsburgh noted in the Pittsburgh Courier, “and I think she's here to stay.” In the newspaper, John Clark applauded Joyner for adding a manicurist in his shop on Wylie Avenue. “With this addition as a part of the regular organization,” Clark proclaimed, “Archeal's Barber Shop is complete as one of the most instructive and interesting barber shops in the city. All are excellent mechanics and artists as well as conversationalists.”31 By celebrating the addition of a manicurist to expand the services offered in this particular shop, Joyner and Clark intimated a new vision for modern black barber shops. For all of the manly excitement of having a feminine service in the barber shop, black men are silent in the available sources on what might have been perceived as a feminine act of getting manicures. Nonetheless, grooming men was not solely a male barber's job, and barbers groomed more than just men.

Figure 14. Harlem barber shop, circa 1929. Courtesy of the Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

Female customers who sought barbers’ skills for a new hairstyle joined manicurists in these predominately male spaces. In the 1920s, more women sat in the barber's chair for the first time during the bobbed hairstyle craze. The bob was so popular that some communities held “bobbed hair contests.” Women participated in the emerging consumer culture of the early twentieth century, where gender identities increasingly became bound with mass consumption and leisure. Their mothers may not have worn such short hairstyles or sat in a barber shop, but these “new women” opted to define for themselves how long or short they would wear their hair, and where they would get it cut.32 The number of beauty shops had been steadily increasing, but the large demand for bobs far outpaced the number of beauty parlors. In fact, many parlors opened their doors to welcome this growing demand, while black and white barbers scrambled to learn how to cut the “Boy Bob.” One man was convinced that half the barbering patronage in Chicago was “composed of women and girls.”33 Black beauty culturists understood that if black women went to barber shops for their bob, then that was one service not performed in the beauty parlor. Roberta Creditte-Ole, a black proprietor of her own School of Beauty Culture in Chicago's Black Belt, warned women the bob was an artistic cut, and they should be careful not to submit to an incompetent barber.34 In December 1926, Gertrude Smith won a bobbed hairstyle contest held at the Manhattan Casino on 155th Street and 8th Avenue in New York City. The Pittsburgh Courier noted that Smith, a manicurist in Marcia Lansing Beauty Shoppe, “wore a long mannish bob cut by Leroy Stokes, of the Elite Barber Shop, and dressed by Ethel Biard, of Ethel's Hair Parlor,” suggesting that even though barbers cut bobs, they lacked the skill, and perhaps the interest, to style it.35 The bob may have facilitated an intriguing moment when women regularly moved between the barber and beauty shop.

Many black barbers opened new, elaborate shops to accommodate women. J. C. Cooper entered barbering at age eighteen in Marion, South Carolina, but “on account of the exodus” north, he made his way to Hopewell, Virginia, then soon after to Richmond. After surveying various sections of the city, Cooper “decided I could do the best for myself, where I was most needed,” which was at 619 Brook Avenue in Jackson Ward. He later moved a few doors down to another space adorned with:

Hot and cold water baths, electrical massages, latest devices for anti-septic shampoos, together with a special department for ladies, where bobbing hair, trimming, shampooing, massaging and special hair treatment with the latest sterilizing outfits will be found available. Coupled with this may be found the most improved and expensive electric lights, seven in all ordered direct from Germany, and a customer, under the cooling breezes from the large electric fan in summer may be as comfortable as he will be from ample heat furnished. We carry also a full line of cosmetics for both male and female trade.36

Cooper envisioned the modern barber shop as his predecessors had, adorned with up-to-date equipment and extensive service options. Even though many black barbers were still grooming white men in Richmond in the 1930s on Main and Broad Streets, barbers like Cooper carefully considered the sartorial wants of a diverse black clientele. Cooper expanded the basic understandings of black consumption and modernity to reimagine the barber shop as a parlor that welcomed men and women—a proposition that the bob made possible.

The bob may have brought barbers more business, but their male customers were much more ambivalent. Men viewed women's entry into the barber shop as an intrusion on their space. African American writer and editor Chandler Owen claimed that men disliked bobbed hair. He cited the theory that opposites attract; men liked women who wore dresses, not knickerbockers, and long hair, not short hair. “All in all,” he wrote, “the bobbed hair craze seems to be but a reflection of the general tendency of the women to become more masculine and the men to become more feminine, both of which square with the fundamental law that unlike poles attract and like poles repel. The feminine woman will like the masculine men, while the masculine men will continue to like the feminine women.”37 While Owen did not speak for all men, his thoughts on gender were quite common.

Owen's comments were not restricted to the bob as a masculine style, but rather it mattered that it was styled in a traditionally male space. If men did not want women inside barber shops, there was little they could do about it, though they tried. White men—particularly barbers—balked at the idea of white women going to black barber shops. Many African Americans across the country believed Atlanta's proposed 1926 ordinance to ban white women from black barber shops was a response to the popularity of the bob. An article in the Pittsburgh Courier noted that white barbers “skillfully took advantage of the craze for bobbed hair and had much to say of the shocking sight” of seeing black men cut white women's hair.38 White barbers had been pushing for years to capture the white male patronage by lobbying for various kinds of regulation. This ordinance was challenged in the courts, which ruled the provision applying to children was unconstitutional.39 The bob may have concerned white men who abhorred the idea of white women occupying the same space with black men, which was what segregation ultimately was meant to minimize. But, in all, the bob did not elicit a crisis in white or black masculinity.

Figure 15. Metropolitan Barber Shop, 1941. Two barbers grooming men at 4654 South Parkway in Chicago. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Figure 16. Oscar Freeman, owner of the Metropolitan Barber Shop, 1942. A woman (note the stockings) appears to be getting a facial in the same shop where a year earlier a photographer took a picture of two men getting a shave and haircut. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Men accepted women as producers (manicurists and barbers) much better than women as consumers. Technically, female consumers were less permanent than manicurists or barbers; however, women exercised their power as consumers on equal footing with men when they frequented barber shops. As barbers, women had to confront the gender politics of skilled work. Had scores of women entered barbering, this shift may have threatened male barbers, but male customers were actually intrigued. In 1935, reporter Enoc Waters, Jr., interviewed Margaret West, a successful barber on the South Side of Chicago. Before getting to the particulars of West's history in the profession, Waters contextualized the gendering of barber shops. “When women began patronizing [barber shops] at the outset of the bobbed hair era,” Waters recalled, “what a hullabaloo was raised by the male clientele which felt that the last stronghold of masculinity was going sissy. Then right behind the women patrons came the manicurists with all their feminine fripperies which sent raw blooded he men, who had for years chewed their plug tobacco and discussed ‘manly’ topics with abandon, scurrying to those places which had not been violated by the invasion of militant feminists.”40 To Waters, women intruded on barber shops. As customers and manicurists, or workers performing feminine duties, their presence was not considered legitimate. But as barbers, as Waters suggests, they performed the same work as men and were somehow less intrusive. “Now comes the lady barber,” he quipped, “a dainty feminine morsel who wields the razor and handles the clippers with the dexterity of a man, but brings in addition a feminine touch to which men are peculiarly susceptible.”41 Although most women who entered the personal grooming service industry became beauticians, a small percentage of women opted to become barbers.42

Margaret West could attest to the ways the sighting of a female barber elicited curiosity in the barber shop and the press. West learned barbering from her father and brother before moving to Detroit to open a shop with her brother, Baby West. Although the shop prospered, in 1929 she moved with her brother to Chicago. Baby West was popular in Chicago, but was something of a wanderer. He left Chicago for New York and opened a shop in Harlem. Margaret remained in Chicago, working at Henry Brown's shop at 35th Street near South Parkway (now Martin Luther King Drive). Paid on a percentage basis, her income averaged $20 to $23.50 per week. West had a large male customer base, which she suggested may have resulted from their sense of “novelty” of being groomed by a female barber. This may have been true of spectators but not customers. If West was not a skilled barber, the novelty of gender would have worn off after a few poor haircuts. Waters reported that Margaret's presence in the shop “rid it of the undesirable traits usually associated with such places. Mr. Brown, the proprietor, has found no reason to post signs reading ‘Please Do Not Use Profanity’ often found in barber shops.”43 Although Waters initially acknowledged West's skills with the razor, he privileged her gender as her greatest asset.

Waters was not the only person at the Defender to focus on the physical appearance of female barbers. After graduating from Tyler, Billie Kirkpatrick cut hair in her husband's barber shop in Sherman, Texas. The Defender published her picture with a caption, “It is no mystery that her presence in the shop has accelerated business.”44 Women had to at once substantiate their presence inside this male space and prove their barbering skills to each customer to convince them to return. Many women capitalized on their gender to get the opportunity to prove their skills. In Monroe, Louisiana, Dollye Vaz was the only female barber in the very popular Red Goose Barber Shop.45 In Cincinnati, Agnes Richardson was the only known black woman to own a licensed barber shop.46 There was nothing manly about being a barber, but being a barber was commonly defined by being a man.

In an attempt to increase their prospective customer base even further, barbers tried hard to dismiss class divisions as a show of solidarity. Although it was a hard sell, George Myers tried to convince a friend he was part of the working class. In 1920, George Myers still groomed white men in his Cleveland barber shop, and in his correspondence with historian James Ford Rhodes, former patron and friend, the two debated Myers's identity as a capitalist or proletarian. Rhodes proclaimed that Myers, because of his financial success as a barber, “cut entirely loose from the proletariat and [is] now in the capitalistic class.”47 Myers replied, “While still identified with the proletariat, I shall at least be able to keep the wolf from the door in my ‘sere and yellow days.’”48 He placed himself, as a barber, in a petit bourgeoisie position not far removed from the black working class. Myers further stated, “While it may be (if success in business counts) that I am classed with the capitalistic class, I am far from a capitalist, and still identified with the proletariat. No barber to my knowledge ever became wealthy enough to get away from them.”49 Myers was far from a proletarian, and how much wealth one needed to “get away from them” is unclear. Still, he understood the unstable position of the petit bourgeoisie. Myers did little to actually identify with the working class and identified with the proletariat only through his prospective leadership of it.

W. E. B. Du Bois extended this relationship between black capitalists and laborers much further. “The colored group is not divided into capitalists and laborers,” he argued in 1921. “Today to a very large extent our laborers are our capitalists and our capitalists are our laborers.” He suggested black entrepreneurs and professionals not only became affluent through manual toil, but also were a generation removed from a laboring class.50 Barbers with black customers exemplified this notion that the boundaries between black laborers and capitalists were blurred. Barbers could boast of being businessmen, independent of an employer, which was no small feat. But while their income did not significantly set them apart from the black working class, it was their status as entrepreneurs who controlled their own time that marked the difference. William Jones, a sociology professor at Howard University, conducted a study of black recreational activities in Washington, D.C., in the 1920s, which included barber shops. He described the barber shops from Fourth Street and Florida Avenue to Fourteenth and U Streets as commercial institutions that satisfy “the cravings for leisure-time activity.” The focus on social interaction led Jones to conclude that “as a social and recreational institution it plays a greater role in the Negro community than it does as a pure commercial agency.”51 Yet commerce and labor were always bound together, which was apparent during the Great Depression.

Cutting Hair During Hard Times

As unemployment rose in the 1930s, African Americans, who were barely able to afford necessities like food and clothing, cut back on expenditures such as haircuts. Yet, next to funeral parlors, barber and beauty shops had come the closest to being recession-proof businesses. Men would always need to be groomed, but the major question was whether, and how often, they would get a haircut in a barber shop. Besides worrying about losing customers or pressures to lower prices, shop owners had to contend with their employees’ demands for better hours and higher percentages of receipts. The growth of a black male urban population encouraged more barbers to open their own shops, but the economic hardships of this population also encouraged them to find ways to weather the storm.

While agricultural and industrial jobs were scarce in the 1930s, African Americans capitalized on the everyday practices of the familial economy that often reproduced gender roles. African Americans with larger families saved money on hair grooming by cutting and styling each other's hair at home. Many men and women learned hairdressing and barbering during these grooming sessions. Joseph Richburg of Summerton, South Carolina—southeast of Columbia—started cutting boys’ hair in the community under a tree and on the front porch. “I started around say in 1930,” Richburg recalled, “cutting one and another's [sic], my brother's hair. See we had a lot of boys, and my daddy, he would work the sawmill during the winter months and ‘boy, you've got to help me do this, you've got to help me do that’ and we got a pair of clippers. Mama use to do it with a pair of scissors before and he got a pair of clippers. Then I had to cut the boys’ hair and they'd cut mine.” But he did not actually enter barbering professionally until he needed money, because he was “courting, you know, going to see the girls so I went to a little place down on Davis Crossroads and I rented a little shop and I cut hair down there for ten, fifteen cents.”52 Work defined the coming-of-age stories for many African American children, especially in the rural South. For Richburg, learning how to cut hair not only allowed him to escape grueling agricultural work, but also allowed him to exercise a producerist notion of masculinity by earning enough money to date girls.

If Richburg wanted to learn barbering more formally, by 1933 he had the option of traveling to Texas to receive training in a black college. H. M. Morgan opened Tyler Barber College in Tyler, Texas, “to teach scientific barbering” to African Americans. This was the first barber school for African Americans. Instructors introduced students to the following subjects: Bacteriology, Hygiene, Sanitation, Biology, Histology, Anatomy, Pathology, Pharmacology, Light Therapy, and Electricity. Morgan reported “twenty-five chairs in the practice department, a laboratory for mixing drugs, chemicals and lotions for the treatment of the hair and scalp and beautification of the skin; lamps that produce the Infra-Red Ray and the Violet Ray, and…apparatus for producing galvanic and faradic currents, and class rooms.” The college had separate dormitories for men and women, suggesting they had a sizable female enrollment. Their numbers increased over the years so that by 1944 women represented two-thirds of the 126 enrolled students. Between 1935 and 1944, Tyler graduated approximately 1,635 barbers.53

These graduates entered the field when fewer people could afford regular visits to barber shops. Some owners responded to the effects of the Depression by joining forces with the white-dominated Associated Master Barbers of America (AMBA) to prevent the price of haircuts from plummeting. In Birmingham in 1935, the local Barbers’ Association, including black barbers, organized to discuss uniformity in prices.54 In 1937, the Illinois Master Barbers Association won a superior court decision that upheld the minimum price for haircuts at fifty cents and the minimum price for shaves at twenty-five cents. Some members of the association violated the agreement and charged below the minimum price.55 A black barber in Chicago believed barbering would be more profitable if his competitors cooperated on prices and standards:

The only competitors I have are Negroes, and the reason the barbering business is not more profitable…is because of the “chiselers”—apprentice barbers who are operating small shops and cutting prices. The average registered barber having a large following can only earn around $22 a week. We have no Negro barber college because young Negro men have no interest in spending their money qualifying to become barbers. The barber standard is low because of the small compensation received for one's work and because a certain shiftless type of individual has represented this profession.56

He was a member of an association of black barbers in Chicago that cooperated with state and city law enforcement agencies to arrest unregistered barbers and owners with “unsanitary” shops. He complained that he had to work longer hours to compete with other black barbers who drove down prices, which, he argued, “deprived me of the opportunity for amusement” or leisure.57

In 1935, twenty-five black barbers in Philadelphia established a separate chapter of the AMBA, Chapter 829. They elected Sidney H. Jones, of North Philadelphia, president of the chapter. Members had to be a manager or proprietor of a barber shop and pay a monthly fee of $1.50. This black chapter cooperated with the three white chapters to lobby for revisions in the city ordinance regulating the field.58 The barbers affiliated with Chapter 829 were a small fraction of the total black proprietors in the city. However, the chapter signaled a shift in interracial cooperation and organization among proprietors. The Depression encouraged this cooperation because some barbers accommodated their customers, who also faced economic hardships, by lowering prices. These associations resembled unions, but instead of pushing for better wages, they fought for better prices.

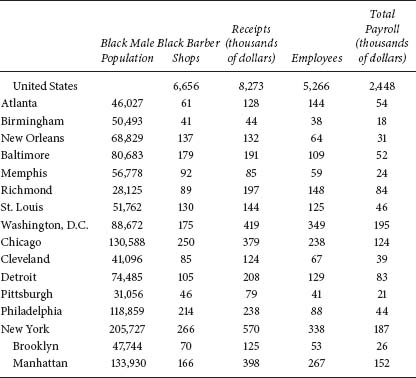

The 1940 United States Business Census reveals the state of black barber shops and the level of competition they faced within black communities during the 1930s (Table 7). There were still a few color-line shops in the South, but most shops targeted black patrons. The 6,656 black barber shops collectively grossed $8,273,000, employed 5,266 men and women, and paid them a total of $2,448,000. The ratio of shops to employees suggests there were a significant number of shops where the owner had no employees. Larger markets like Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia had the most black barber shops, but upper-South cities such as Baltimore, Washington, D.C., and St. Louis were close behind. The ratio of barber shops to the black male population shows very little uniformity by region or market size. In Richmond, there was one black barber shop for every 316 black men, whereas in Birmingham, there was one shop for every 1,241 black men. A high shop-to-consumer ratio suggests more competition between shops than in cities with lower ratios. Richmond, St. Louis, Baltimore, Cleveland, New Orleans, Washington, D.C., and Chicago had higher shop-to-consumer ratios than the other cities.

Table 7. Black Barber Shops, Receipts, Personnel, and Payroll for Select Cities, 1940

Source: United States Department of Commerce, Sixteenth Census of the United States: 1940 Census of Business; Sixteenth Census of the United States: Population Statistics.

The financial data for these barber shops highlight the hardships they endured during the Depression. On average, black barber shops grossed $1,243 in 1939. Of the cities in the sample, only in Washington, D.C, Richmond, New York, and Atlanta did the average shop gross over $2,000. As hard as the Depression hit most people, black residents were surprised to see barber shop owners doing well. A black resident in Jackson, Mississippi, noted, “Most of us were really struggling, but some Negroes were doing well. One Negro man, Barber Jones, drove a Rolls Royce. We didn't know how he got the money because he only serviced Negroes in his barber shop.”59 He indicated that had Jones serviced whites, people might better understand how he could afford a Rolls Royce. Shop proprietors exercised their consumer power by purchasing a fashionable car. In an oral interview, Julia Lucas recalled meeting her first husband, Charles H. Herndon, a barber thirty-two years her senior, in Durham, North Carolina, and noted his Buick was the biggest car she had ever seen. When Lucas finished college in 1938, she started working as a bookkeeper in Herndon's shop.60 On average, owners paid their employees $465, which was 30 percent of total receipts. Atlanta, Memphis, and St. Louis were the only cities in the sample that paid their employees below the average. However, the average owner in New Orleans, Baltimore, Memphis, Philadelphia, and Pittsburgh distributed less than 30 percent of receipts to employees. For example, for the average black barber shop in Philadelphia, the payroll was only 19 percent of total receipts. It is likely that there were more one-person shops in Philadelphia than other cities because these shops would bring the percentage down. However, the larger significance is that black shop owners believed prices were depressed and journeymen barbers believed they were not paid enough. As a result, both owners and employees organized in their own interests.

In the 1930s, shop owners increasingly supported journeymen barbers in the labor movement.61 Like other black workers during the 1930s, a growing number of black journeymen barbers overcame their skepticism toward the labor movement and entered the “house of labor.”62 In 1939, members of the Barber and Beauty Culturists Union, Local 8 of Harlem, affiliated with the Negro Labor Committee, actively attempted to organize black journeymen barbers to pressure shop owners for better commissions and working conditions. Frank Crosswaith, chairman of the Negro Labor Committee (NLC), worked with Local 8 on their strategies to organize more barbers into the union and push for a city ordinance to regulate barbering. Crosswaith and union members posted numerous flyers to encourage local barbers to attend weekly NLC organizing meetings at the Harlem Labor Center at 312 W. 125th Street. They articulated their labor issues in terms of manhood rights. “A NEW DAY is Now DAWNING for Harlem Barbers,” one flyer proclaimed while encouraging barbers to attend a meeting on March 21. “A day that will see us rise like men out of the swamps of depending upon tips and a commission onto the high ground of manhood enjoying a decent wage, reasonable working hours, union protection and our self-respect.”63 White barbers and black caterers had also been debating the tipping system since the early 1900s. They argued that tips degraded their status as skilled workers by tying their masculinity to the value of their production.

The union organized a meeting with the Master Barbers to discuss a contract that addressed decent wages and larger issues of their exclusion from Social Security. A flyer announcing a meeting asked, “Is there any reason why barbers should be left out of the Social Security Act? Is there any reason why a barber should not know how much he will take home to his family after a week's work? Is there any reason why a barber should earn less than a W.P.A. worker?”64 The Social Security Act covered regular wage workers (non-mobile or seasonal) in large industries or companies, with at least four employees, whose contributions could be easily collected.65 Barbers were not regular wage workers because a portion of their wages was a percentage of their receipts.

On November 30, 1939, delegates from Local 8 attended a City Hall conference with Mayor Fiorello La Guardia and Newbold Morris to discuss the pending barbers’ license law that had been before the City Council for six months. George DeMar, special organizer for Local 8, suggested that a license law would eradicate many of the “unwholesome” conditions in barber shops. He believed the bill would “go far in eliminating vice and crime together with generally improving the conditions under which Barbers’ work and public health suffers.” Union organizers abhorred shops that allowed gamblers to operate their racket from the barber shop, and they appealed to journeymen with similar objections.66

The economic hardships that spurred the black working class to join unions and fight for higher wages also encouraged black business owners and intellectuals to increasingly advocate for a separate black or group economy, a “Negro market,” or a nation within a nation. The separate economy consisted of two segments of businesses. The first included local, small proprietorships such as barber shops, beauty shops, grocery stores, and tailor shops. Service businesses comprised the largest number of black proprietors. Barber shops and beauty shops made up over 40 percent of these service businesses. The second segment included businesses that participated in capital-intensive industries such as banks, insurance companies, and real estate firms.67 Booker T. Washington and later Marcus Garvey had long championed the development of a black commercial sphere. In the mid- to late 1920s, the NNBL urged black consumers to “Buy Something from a Negro Merchant!” Through its local chapters, the NNBL sponsored a number of programs, such as the “National Negro Trade Week,” to channel the growing black consumer dollars to black-owned businesses.68 These pitches for separatism were largely seen as black extreme political views, which were either a conservative retreat from political pressure or a nationalist call for racial solidarity. The increase and concentration of urban black populations and the economic crisis created the conditions for a renewed interest in black self-help. Barbers were active in Washington's NNBL and supported business development, but they did not have to convince black consumers to get a haircut from a black barber in the way a grocer had to join the NNBL in its clarion call to “Buy Something from a Negro Merchant.”

Despite the passionate and pragmatic visions of a separate black economy as a strategy of survival in the 1930s, black consumer activists and intellectuals failed to see black barber shops as a critical component—along with beauty shops and funeral parlors—of a group economy. W. E. B. Du Bois argued that a new economic solidarity was paramount in the age of economic crisis during the Great Depression. All workers felt the pain of economic hardship, but black workers felt it harder and its effects more permanent. In offering a solution, Du Bois and other advocates of a group economy believed African Americans could capitalize on a captive market that resulted from segregation. “Separate Negro sections will increase race antagonism,” he conceded, “but they will also increase economic cooperation, organized self-defense and necessary self-confidence.” He recognized his opposition to Booker T. Washington's economic strategies of uplift decades earlier, but reasoned that new economic hardships required new survival strategies.69 To be sure, black entrepreneurs and intellectuals were at the forefront of encouraging a separate economy. Black consumers simply wanted jobs, fair wages, and fair prices. The black working class launched “Don't Buy Where You Can't Work” campaigns in various cities.70 This revealed the “paradox of early black capitalism.”71 While these were economic boycotts, they were also social movements that addressed issues of access and respect. If these campaigns were successful, and the slogans taken literally, black consumers’ and workers’ increased access could translate into a decrease in sales for black businesses. Many black businesses, however, saw the opportunity and increased their marketing appeals to keep consumer dollars within black communities. Yet, African Americans could work in black barber shops, and these shops did not have to convince black consumers to patronize them. In many ways, the businesses of grooming the living and the dead were at the heart of a separate black economic sphere that other business owners had hoped would develop.72

Black barber shops could not provide the economies of scale that advocates of a separate black economy had in mind, such as hiring large numbers of black workers. In fact, many of the early critics of a “separate Negro economy,” such as E. Franklin Frazier, pointed to these small, service-based enterprises as evidence that “black” business was a myth propagated by the black bourgeoisie to bolster their own class status.73 But black culture was the value that barbers and their shops offered—to their customers and the idea of a group economy—that took more of an effort for commodity-based businesses to replicate. Black consumers patronized black barber shops not simply because they were black, but because black barbers were skilled at cutting black men's diverse hair types. In the 1930s, black consumers did not attempt to patronize white barber shops, unlike their attempts to eat in white-owned restaurants and stay in white-owned hotels. Personal service work required an intimate relationship where the patron trusted the barber to make him look good. If he were pleased with the barber's work, he would likely continue to patronize this particular barber, thus becoming part of the regular waiting public in the shop. Working-class men typically filled barber shops on weekends because they had time off work. On a Saturday, men from the surrounding neighborhood could be found in the barber shop getting a haircut or shave for the evening's outing at a juke joint and for Sunday morning's church service. Some men frequented the shop not just for a haircut—or not for a haircut at all—but also to hang out with friends. As men waited for their turn in the barber's chair or stopped by the shop to occupy idle time by talking with other men, black barber shops became more than places of business; they became public spaces.

Congregation and Conversation in the Shop

Black men coped with the Great Depression in many ways, and the barber shop functioned as a central place where they could socialize and talk with friends and strangers. Black barber shops were among the few public spaces where African American men could congregate, socialize, and talk outside of white surveillance or a large female presence. The racial and gender privacy of the space enabled a level of truth-telling where black men could critically discuss racial politics. It also enabled a level of truth-stretching where they could fashion themselves as men in ways that would draw more opposition in a Jim Crow society. Black male congregation and conversation, then, defined the culture of modern barber shops. Black entrepreneurs, such as gamblers and the black press, also tapped into this barber shop culture, thus contributing to the commercial public sphere.

The public and private nature of black barber shops made them attractive legal businesses where illegal businessmen could operate their underground economy. In 1933, for example, Arthur Gholston, real estate owner and member of the Chicago Police Department, accused Thomas P. Weathersby, former owner of the Vendome barber shop, of conducting a den of commercialized vice inside his shop on 127 East 47th Street. Gholston told the police he had been walking along 47th Street when two girls stopped him at Prairie Avenue. He said they “took” him to Weathersby's barber shop and went to the basement, where they purchased beer. Gholston reported that he later discovered $33 missing from his pockets. He alleged the girls placed “knock-out” drops in his liquor. Gholston later filed a complaint in municipal court claiming that Weathersby was a “keeper of a disorderly, common, ill-governed house for the encouragement of idleness, gambling, drinking, fornication and other mis-behaviors.” Weathersby was tried and found not guilty, but he was unable to establish another business because his license was revoked. He later sued Gholston and police officials for slander and libel.74

Barber shops, along with cigar stores, were common places for African Americans to play the numbers or “policy,” an underground lottery run, because gambling operators used these legal businesses as public fronts to divert suspicion of their illegal activities inside. Many African Americans played the numbers to weather the Depression years. Customers and passersby made their picks with the runner at the barber shop, for example, for as little as a penny. James Mallory and R. Butler of Pittsburgh were arrested for operating a lottery inside Butler's barber shop. The judge released Butler but fined Mallory twenty-five dollars and gave him a lecture for not upholding his “Godly” principles as deacon of the North Side church.75 The police arrested barber Joseph Sharper of Addison Street near 17th Street in Philadelphia because they alleged he “would suggest a winning number after trimming each customer's hair.”76 In Washington, D.C., Needham Turnage, United States commissioner, ordered forty-six-year-old William Hooper, a barber on 486 L Street Southwest, “held for the action of the grand jury on charges of writing numbers and possessing slips.”77 The very nature of the underground economy required a level of privacy outside the boundaries of authoritative surveillance. The barber shop provided the ideal combination of a private space in the public sphere, where anyone could play his or her numbers outside of the presence of law enforcement.

During the interwar period, numbers running was the largest black business in the informal economy, and its connection with key black businesses in the formal economy gave it legitimacy. To be sure, the African American working class did not view playing the numbers as an illegal operation, in contrast to law enforcement—at least those not being paid off. Many African Americans saw the numbers game and its operators as positive forces in black communities because they employed people and used their profits to build institutions.78 A black resident of Detroit noted, “Everyone played either the numbers…or policy or both…it offered its players daily chances to pick up on a few quick bucks without any questions asked. It was very popular…because it was inexpensive and convenient.”79 Players sometimes placed their pick with a “walking writer,” but players were concerned the writer would run off with their money. An established business or “policy station” was much preferred.

Business owners wanted to provide as many services to their customers as possible. Many barber shops and other small businesses stayed solvent because of their association with numbers running. Station owners were allowed to keep 25 percent of the gross business they wrote. A Chicago restaurateur reported, “Two years ago, my business was so bad that I thought I would have to close up. Then I thought of a policy station. I divided the store, and I find that I make more money from the policy than from the lunchroom.”80 Players who did not want to frequent illicit spaces to place their daily pick could stop in the local restaurant, grocery store, or barber shop. Some barber shops had a back room where the station operated. St. Clair Drake and Horace Cayton noted that in a selected area of Chicago's Black Belt in the 1930s, there were fifty policy stations. Thirty-three stations had no front; five were in shoeshine parlors, four in barber shops, and two each in beauty parlors, candy stores, cigar stores, and delicatessens.81

In addition to numbers operators, the black press also partnered with black barber shops. In fact, the waiting public embodied the ideal market for disseminating news and increasing readership. Southern rural residents, in particular, could leave news of local happenings at the barber shop to be picked up by a Chicago Defender agent and included in the next edition of the paper.82 In Chicago, the Defender maintained bulletin boards at Lowis’ Drug Store, on 47th Street and South Parkway, and the Metropolitan Barber Shop, on 4652 South Parkway, to inform black residents of the latest developments on the Ethiopian war front in the 1930s, and to display photos of “nationally famous characters” that appeared in the newspaper.83 The black press was very creative in distributing its papers to its readers by arming the Pullman Porters with copies to distribute on their routes and making them available for sale in barber shops.84 Northern and southern African American men purchased the Defender and other black newspapers from the local barber shop and often discussed its contents.85

Barber shops were ripe for conversation and debates among gathering men, but it was the privacy and security of the shop that allowed such gatherings to take shape. In a three- or four-chair shop, waiting customers occupied their time in various ways. Most men talked or argued about issues of the moment. It is not surprising that a group of people—sitting, waiting; if not comrades, then reasonably acquaintances—collectively discussed various issues of the day. African American men congregated in barber shops and discussed sports, racial and electoral politics, and the everyday news and events that occurred in their local communities. “The barbershop was a place where they gathered and talked about a lot of things,” Julia Lucas remembered about her barber shop, “and [they] knew that it was secure with the people with whom they were talking. We didn't have that many private places, other than churches, where we could discuss anything that concerned black people's advancement and where they felt secure. A place does make a difference in how you express and when you feel free to express something that you know is controversial. But the barbershop was one of the places that people could go.”86 And people went, and talked, regularly.

In barber shop forums, as they were often referred to in the 1930s, African Americans could be found discussing the “mighty prowess” of the “Brown Bomber,” Joe Louis, exhibiting the racial pride that emanated from his performance. In the 1930s, Louis became a black folk hero for African Americans, giving them hope of vengeance against segregation. But, Louis was not a distant folk hero out of reach from those men who discussed his success, because he also patronized black barber shops. In early September 1935, Louis went inside Elie's Barber Shop in Harlem for a trim. Word quickly spread that he was in town, and within ten or fifteen minutes, reporters claimed there were “5000 people crowded between 135th and 136th streets on Seventh avenue, blocking traffic, breaking the windows in the parked autos, and causing his body guards to call the police reserves for help.” Another reporter noted, “When he stops in a barbershop the barbers neglect the other customers to get a close-up of their idol and the way crowds rush into the shop, in front of the doors and windows, is almost beyond the imagination.”87 When Louis dropped into a barber shop on the North End of Boston, word quickly spread among young children of the area, who rushed to the shop to see their idol. Louis treated a few of them to lessons on the correct boxing stance.88 At the barber shop, African Americans could get close to Louis in a way that his celebrity status otherwise made impossible. Even if onlookers missed the opportunity to talk with Louis because of the large crowds peering through the shop window, he became a “real” person who visited everyday spaces where African Americans regularly congregated.

Black communities were not lacking in organized political, social, or economic meetings at local churches or fraternal halls. However, conversations inside barber shops were not organized and participants were not preselected. On average, they were not at the shop for a meeting or to discuss any particular issues. They were there for a haircut or to socialize with friends, barbers, and other customers. And those customers were not all men. Charles Herndon had a pool table, for recreation not gambling, in back of his Durham shop. Julia Lucas recalled that when workers from surrounding businesses and the tobacco companies had a lunch or dinner hour, they “would come down and play pool, get their hair cut, or a shave. It just became a place to meet people and I was right in the middle of it.” And so was the female barber who worked in the shop. Because of Lucas and the female barber, women “felt comfortable” going to this shop, and even playing pool in the back. Lucas remembered that “people talked about everything in the barbershop…from who went out with whom, where you go to church, who are good church people, and who are the nothings.”89 Barbers or customers might engage in conversation with one or two people, which might invite others to offer input or counterarguments. Although typical barber shop conversations were not organized, there were a few established protocols that most men adhered to inside the shop. The shop customers accepted any protocols or interventions made by the owner. The owners left the multiple, separate conversations among groups of two or three men to be organized among them. When everyone in the shop discussed the same issue, the owner typically facilitated discussions by making sure speakers were not interrupted. Barbers, then, were key facilitators of the social interactions in the shop.

The networks of people who frequented barber shops made them important spaces for news and information in the black public sphere. An argument in a New York barber shop turned into a breaking-news story for a black newspaper reporter, Ralph Matthews. Two men in a barber shop got into an argument about whether Father Divine had gotten married again. Father Divine was an African American spiritual leader who founded the International Peace Mission Movement with a significant following in the black community. “One said Father Divine was talking ‘spiritually’ when he said in a sermon he had just married the ‘Lamb of God.’ The other thought [maybe] he was married ‘sho’ nuff.’” Overhearing the argument, Matthews followed up on the scoop, “discovered the term ‘legal’ in the sermon, and wrote a speculative story.” Reverend Albert Shadd confirmed he had officiated the nuptials of Father Divine and Edna Rose Ritchings, a twenty-one-year-old Canadian white girl.90 The Divine argument was not the first time a discussion from a barber shop was further explored in the Chicago Defender.

In 1944, George McWhorter, a customer in a Chicago barber shop, sought the assistance of reporter Lucius Harper to help him answer a perplexing question that arose during “one of those famous ‘barber shop arguments.’” A former Louisiana resident “stumped” everyone in the barber shop when he argued that during slavery, free blacks purchased and owned white men. McWhorter said, “From all sources and sides our Louisiana friend was howled down.” McWhorter posed the question, though a much broader one, to Harper regarding evidence of southern or northern free blacks purchasing white or black men during slavery. Before answering the question in his Defender column, “Dustin’ Off the News,” Harper identified the importance of barber shops as spaces of political discourse. He wrote:

As we observe, this question arose in the barber shop, one of America's greatest open forums. Here, amid the clatter of scissors, the hum of electric clippers and the like, more questions of local, national and international moment are brought to light, debated and settled forthwith than are discussed on the floors of congress in probably two weeks. Our American barber shops are the only places where anyone can immediately become “Speaker of the House” without the benefit of ballot. However, it is one of the most cosmopolitan institutions in our community life. Around its chairs were molded into thought and actual life some of America's largest and most prosperous Negro business enterprises.91

Harper reported that some free blacks owned slaves, but they did not own white men. However, he did report that in 1833 George White, “the Negro town crier,” purchased a white wanderer at a public auction under the Illinois vagrancy law. Harper suggests that barber shops were egalitarian institutions where everyone had equal authority regardless of social standing. He also intimated black men's engagement in politics and political discourse outside of parties and polls. Being “Speaker of the House” in the barber shop gave one the authority to be heard, make claims, and draw conclusions.

Whether barber shops were egalitarian or not often rested with the shop owners. They alone could determine how political, democratic, or radical the conversations could play out. During the 1930s, barber shops served as private spaces to discuss labor politics. In Charles Herndon's shop, the black tobacco workers were proud to be in the union and they, “especially the younger men and women,” enjoyed talking about it. Herndon's wife and partner noted, “they talk about what they were going to organize and what they were going to ask for. It was the beginning of a revelation to me, how blacks would say, ‘I'm all fed up, and I can't take it no more. We're going to do something about it.’ And they would discuss it.”92 They were comfortable discussing labor politics because of Herndon and Lucas. But Lucas's presence in particular was critical for this shop to be a truly egalitarian and democratic space, with men and women engaged. After Herndon died in 1941, Lucas took over the shop and renamed it the Palace Barber Shop.93 Few shops could boast of such an atmosphere, but some might have preferred a shop without a large presence of women. Even Lucas noted women would not go in certain barber shops. Shops with predominately male barbers and customers still provided a space to discuss issues men preferred not to discuss elsewhere.

From New York to Alabama, black men who joined the Communist Party would share party rhetoric and news with others in barber shops. Al Jackson was a black communist and barber shop owner in Montgomery, Alabama. Undoubtedly because of his leftist affiliation, communist leaflets were often left in his shop “for organizers who regularly came by for a trim.”94 This is not to suggest that all of Jackson's customers were communists, but any affiliation with the communist party was a subversive act in the eyes of white authorities. Yet, Jackson was able to publicly share communist literature in the privacy of his barber shop. As a communist, he knew what he was talking about when the issue came up. Having solid information, or knowing more than others about an issue, could establish authority but also stilt conversations. After attending a ten-week course at the Workers School in New York in 1934, Hosea Hudson returned to Birmingham, Alabama, eager to share his new insights on imperialism, fascism, and socialism with fellow black residents. The barber shop beckoned. “I'd be discussing socialism in the barber shop,” he recalled. “We'd start the conversation off, then we'd talk about socialism, and how the workers’ conditions would be improved under socialism…. They'd sit down there and wouldn't no one ask no questions, wouldn't interrupt what I'm saying. They wanted to see what I had to tell.”95 Hudson could be quite persuasive, so it is not surprising few people challenged him. As a steel-mill worker and union official, he regularly extolled the virtues of radical resistance to economic exploitation, and he had a crowd sitting around the barber shop listening to him sound the drum.