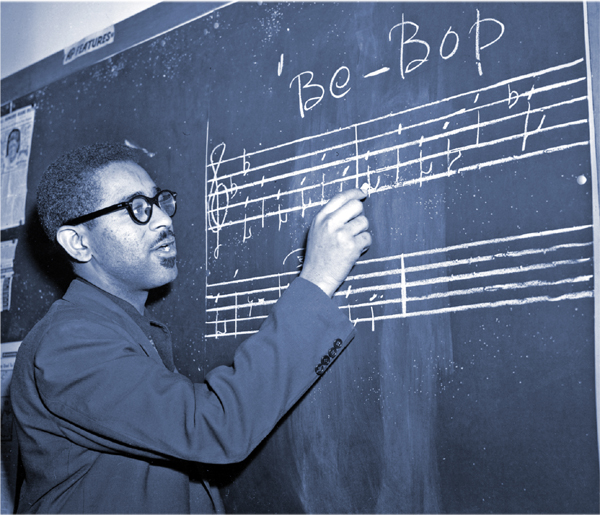

Dizzy Gillespie in 1955

Dizzy Gillespie in 1955

Four-year-old John Birks Gillespie’s favorite toys were somewhat unusual. They consisted of an assortment of musical instruments. Among the many instruments in the parlor of the Gillespie home were a piano, clarinet, guitar, mandolin, bass fiddle, and a set of drums. John’s father, James, a bricklayer, was also an amateur musician. He was the leader of a local band, and he stored the band’s instruments in his home. Of course, these musical instruments were not really John’s “toys.” But nothing made young John happier than getting his little hands on the various instruments and making sounds on them. Not surprisingly, John would later make history with his exciting jazz sounds.

John Birks Gillespie was born on October 21, 1917, in Cheraw, South Carolina, to James and Lottie Gillespie. He was the youngest of their nine children. While growing up, John had plenty of opportunity to learn about many different kinds of musical instruments. He also got to hear a lot of music, listening to his father’s band during rehearsals and performances. Unfortunately, James Gillespie died when John was ten years old. By this time John loved music more than anything else, but there was nobody to guide him.

When he was fourteen, John joined the band at the Robert Smalls High School. He was assigned to play trombone. Although he quickly taught himself the basics of how to produce a sound and play different notes, he switched to the trumpet several months later. His idol at the time was the trumpet player Roy Eldridge. Each week, John listened to radio broadcasts of Teddy Hill’s band from New York’s Savoy Ballroom. Eldridge was the band’s featured trumpet player. John was inspired by Eldridge’s exciting solos.

John practiced his horn at every spare moment and taught himself as much as he could about the trumpet. His hard work paid off. In 1933 John won a scholarship to study music at Laurinburg Institute, an African-American vocational school in North Carolina. He continued to develop his trumpet skills at Laurinburg, where he also studied piano and music theory. In 1935, John left Laurinburg shortly before his graduation in order to move to Philadelphia with his family.

In Philadelphia, John had enough confidence in his playing to get gigs with various small groups. Then he joined Frank Fairfax’s big band. Trumpet player Charlie Shavers taught him how to play Roy Eldridge’s trumpet solos. But he also advised John to develop his own style instead of copying others. While John was playing with the Frank Fairfax Band, the other band members could not help but notice that he was always clowning around. Someone gave him the nickname “Dizzy,” and it stuck.

In 1937, Gillespie moved to New York City and joined Teddy Hill’s band. He traveled to Europe with the group that summer. He soon became the group’s first trumpetthe featured trumpet soloist. He thus filled the same role that Eldridge had held before him.

The following year, he married Lorraine Willis. In 1939, Gillespie joined Cab Calloway’s band. Among the many fine musicians in the group was bass player Milt Hinton. He encouraged Gillespie to keep working on his own original ideas. Gillespie began participating in jam sessions, informal gatherings of musicians to play improvised jazz at Minton’s Playhouse, a club in Harlem. There he and other musicians such as pianist Thelonious Monk were developing a new style of jazz that came to be called “bebop.”

One day in 1940, when the Cab Calloway band was playing in Kansas City, Gillespie was introduced to a young sax player named Charlie Parker. An impromptu jam session was arranged. According to Gillespie, “I was astounded by what the guy could do.… Charlie Parker and I were moving in practically the same direction too, but neither of us knew it.”1 At the time, Gillespie was playing like Eldridge. But from then on, he began to play more and more like Parker, without intending to copy his style. According to Gillespie, “Lorraine told me one time, ‘Why don’t you play like Charlie Parker?’ I said, ‘Well that’s Charlie Parker’s style. And I’m not a copyist of someone else’s music.’ But he was the most fantastic musician.”2

Meanwhile, Gillespie began to have problems with Calloway. According to Gillespie, “Monk and I would work on an idea. Then I’d try it out the next night with Calloway. Cab didn’t like it. It was too strange for him.”3 Nor did Calloway appreciate Gillespie’s clowning around. Eventually in 1941, the two had a fight, and Calloway fired Gillespie.

Gillespie played briefly with singer Ella Fitzgerald. Then he joined the Benny Carter Sextet. In 1943 Gillespie played with pianist Earl “Fatha” Hines, and the following year with singer Billy Eckstine’s band. Charlie Parker was in both of those bands.

During these years, Gillespie and Parker participated in countless jam sessions, informal practice sessions, and rehearsals. Here they established the guidelines for the bebop style of jazz. According to pianist Billy Taylor:

In 1945 Parker and Gillespie left Eckstine’s band. They made recordings together and then went to California, where they played for a while at Billy Berg’s, a Hollywood club. Unfortunately, the engagement was a flop. Gillespie went back to New York, where he organized a big band to play bebop.

Gillespie recorded many hits, including his compositions “Night in Tunisia” and “Salt Peanuts.” He was also involved with a style of music known as Afro-Cuban. He had always loved Latin music and had sought to combine elements of Latin and African rhythms with jazz. According to Gillespie, “the people of the calypso, the rhumba, the samba and the rhythms of Haiti all have something in common from the mother of their music. Rhythm. The basic rhythm, because Mama Rhythm is Africa.”5 His biggest recorded hits along these lines are his compositions “Manteca” and “Tin Tin Deo.”

Dizzy Gillespie writes an example of bebop music on a blackboard in 1947.

In 1953, someone fell on Gillespie’s trumpet, bending the bell upward. Gillespie claimed he could now hear the sound quicker. After that, he had all of his horns made with the bell pointing up, and this became a trademark. From the 1950s on, Gillespie toured constantly. In 1956, the U.S. State Department sent Gillespie and his band on a tour of the Middle East, Asia, Africa, and Eastern Europe. Gillespie brought live jazz to millions of people who had never heard jazz before. Like Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington, Gillespie became an ambassador of jazz.

Dizzy Gillespie performing in 1989. He said the angle of his trumpet improved the sound.

Always concerned about civil rights issues in the United States, Gillespie threatened to run for president in the 1980s. He said that if elected, he would rename the White House the Blues House and appoint Miles Davis as head of the CIA.6

In 1989, Gillespie visited twenty-seven countries, appeared in a hundred U.S. cities, performed with twenty-eight symphony orchestras, and gave three hundred performances. In 1992, he celebrated his seventy-fifth birthday by playing an eight-week gig at a club in New York. He died of cancer on January 6, 1993. Gillespie’s message about what he tried to communicate through jazz is just as relevant today as when he spoke these words: “I’m playing the same notes, but it comes out different. You can’t teach the soul. You got to bring out your soul on those valves.”7