Charlie Parker, photographed between 1940 and 1955

Charlie Parker, photographed between 1940 and 1955

You do not become an accomplished jazz musician overnight. Years of hard work—long hours of practicing every day—are required to gain the theoretical knowledge and technique you need in order to make your mark in the world of jazz. Young Charlie Parker learned this lesson the hard way. Eager to jam with some older jazz musicians, he went to a local club in Kansas City, the High Hat, only to suffer a humiliating setback.

According to Parker:

Fortunately, young Charlie didn’t give up. He was determined to prove to himself and others that he had what it took to become a great jazz musician. Practicing the saxophone became the only thing that mattered. According to Parker, “I put quite a bit of study into the horn.… In fact, the neighbors threatened to ask my mother to move once … they said I was driving ’em crazy with the horn. I used to put in at least eleven, eleven to fifteen hours a day.”2

Whenever he learned a new tune, Charlie would learn how to play it in all twelve keys. This way he would always be able to transpose from one key to another in an instant. He studied the recordings of all the great jazz musicians of the day, especially the sax players such as Lester Young. In this way Charlie taught himself how to play jazz.

Charles Christopher Parker, Jr., was born in Kansas City, Kansas, on August 29, 1920, and raised across the river in Kansas City, Missouri. At the time, Kansas City was a wide-open town of dives, honky-tonks, and jazz spots. Charlie was the only child of Charles Parker, Sr., and Adelaide, known as Addie. Charlie’s father worked as a tap dancer in vaudeville theater and as a chef on the railroad. He was away from home much of the time Charlie was growing up, and he moved away for good when his son was eleven.

Addie rented out rooms in their home and also worked as a maid. She was devoted to her son and pampered the young boy. When Charlie was eleven, he told his mother he wanted to be a musician. He had heard Rudy Vallee play saxophone on the radio and said he wanted to play like him. So Addie bought Charlie an alto saxophone. He began playing it, but at the time was really not motivated to practice. However, Charlie played alto and baritone sax in his school band.

By the time Charlie was fourteen, he was spending a lot of time hanging out around the doorways of local bars and nightclubs. According to writer Studs Terkel:

It was around this time that Charlie got laughed off the bandstand while trying to jam with the other musicians. After this, he practiced incessantly, learning one tune at a time. Around this time, Charlie was in an auto accident. He was given morphine to ease his pain. He would spend much of the rest of his life obsessed with getting high, especially on heroin.

Addie hoped to save enough money to send Charlie to college. Charlie, however, was not a good student and dropped out of school at the age of fifteen. On July 25, 1936, when he was almost sixteen, Charlie married Rebecca Ruffin. He began playing with the Deans of Swing, a local dance band.

A son, Francis Leon, was born to Charlie and Rebecca on January 10, 1938. By this time, Charlie was unhappy in his marriage. He also was growing bored with the music he played with the Deans of Swing and some other local groups. He felt he was not growing as a musician. For Charlie it was time to expand his horizons. In 1939, Charlie and Rebecca were divorced. Charlie headed for Chicago and from there he moved on to New York City.

Parker’s first job in New York was working as a dishwasher for nine dollars a week. At this time he heard Art Tatum, the speed-playing piano virtuoso. Tatum’s style greatly influenced Parker. In order to work as a musician in New York, Parker had to become a member of the musicians’ union. Once he got his union card, he was able to work in New York clubs. He got a job with pianist Jay McShann’s band, a group he had briefly played with back in Kansas City. The band played in New York and also did gigs in other cities around the country. He stayed with McShann until 1942.

During this time he developed a method of playing the sax that he had been searching for. Parker’s big breakthrough happened one night while he was jamming at a place called Dan Wall’s Chili House. According to Parker:

Parker took part in jam sessions at Minton’s Playhouse and Clark Monroe’s Uptown House, two nightclubs in Harlem. Among the musicians he jammed with were trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, pianist Thelonious Monk, and drummer Kenny Clarke. According to Gillespie, “When Charlie Parker came to New York, he had just what we needed. He had the line and he had the rhythm. The way he got from one note to the other and the way he played the rhythm fit what we were trying to do perfectly. We heard him and knew the music had to go his way.”5

According to drummer Kenny Clarke:

Charlie Parker, known as “Bird,” on the saxophone. He developed a unique way of playing jazz.

The new musical style of jazz Parker and the others played came to be known as bebop. The music was characterized by dazzling high-speed improvisations, complex melody lines, and sophisticated harmonies. The bebop musicians wanted to play music that was so difficult that other musicians could not copy it. At his best, Parker could play hundreds of notes per minute.

According to Studs Terkel, bebop “didn’t happen overnight. Neither did it come out of a void. Bebop was a progression from the jazz forms that preceded it. It drew from all the musical traditions that had been part of the Black experience in America—and from its African roots.”7

For the next few years, Parker played alto sax with various groups. In 1943 he played with pianist Earl “Fatha” Hines, and the following year with singer Billy Eckstine’s band. Dizzy Gillespie was in both of those bands. Parker and Gillespie left Eckstine’s band and went to California, where they played for a while at a Hollywood club.

When Gillespie went back to New York, Parker formed his own small group, which featured Miles Davis on trumpet. Davis was one of the younger jazz musicians who admired Parker and sought to emulate his style. Meanwhile, the Los Angeles music critics and the public did not react favorably to Parker’s music. Feeling pressured, Parker sought solace in alcohol and drugs. One day he set fire to his hotel room bed. Suffering a nervous breakdown, not his first and certainly not his last, Parker was committed to Camarillo State Hospital.

Six months later, Parker was released from the hospital and traveled back to New York. He began performing and recording with some of the greatest jazz musicians of the day, including Miles Davis and Max Roach. For the next nine years, Parker was the most influential player in jazz. In spite of a difficult personal life that included two more failed marriages, two suicide attempts, the death of his young daughter, numerous mental and emotional breakdowns, and addiction to drugs and dependence on alcohol, Parker proved to the world that he was indeed a musical genius.

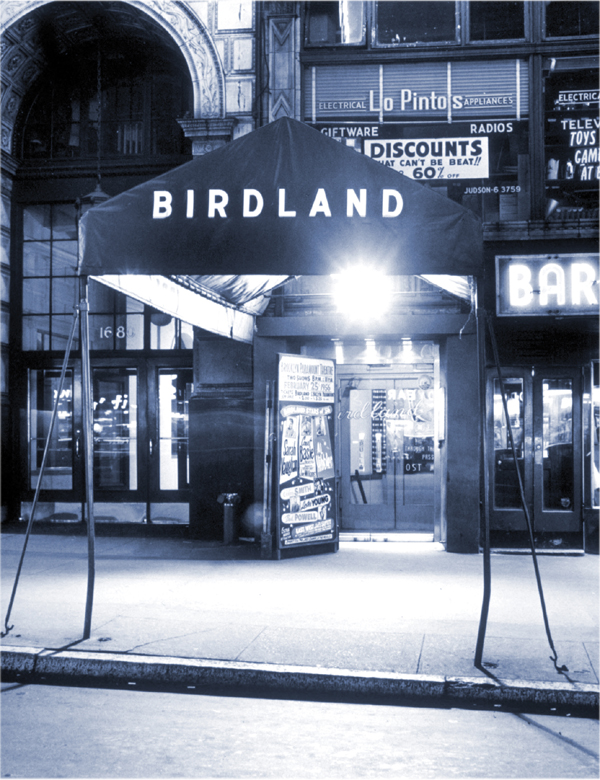

Birdland, the jazz club named for Charlie “Bird” Parker

During the last nine years of his life, Parker played in the best jazz clubs in the United States and made three European tours. Among his greatest recordings are the tunes “KoKo,” “Chasin’ the Bird,” “Ornithology,” “Yardbird Suite,” and “Scrapple From the Apple.” A 1949 album, Charlie Parker With Strings, featuring the tune “April in Paris,” was particularly successful. That year, a jazz club in New York at the corner of Fifty-Third Street and Broadway was named after Parker—Birdland.

Charlie Parker’s last public performance was on March 5, 1955, at Birdland. Seven days later, he died of cirrhosis of the liver and a heart attack. He was only thirty-four years old. In a relatively few short years, Parker had done so much to change the direction of jazz. Many have attempted to explain just how he was able to do it. But no explanation was fully adequate. Perhaps Bird’s own explanation is the most useful: “It’s just music. It’s playing clean and looking for the pretty notes.”8