MY OWN BROADCASTING career underwent an important development when in 1963 I was appointed the first-ever BBC Cricket correspondent. I continued all my commentary (still at that time exclusively for television) but I was also partly allied to the News Department. Whereas in the past they used to read out reports of Test matches from the tapes, now that they had their own correspondent, they decided to risk taking live reports straight from the ground into the news. They considered it a risk because a news bulletin has to be the exact length allotted to it – usually ten minutes – to the nearest second. They were naturally worried about trusting a commentator to do exactly the time they asked for, generally a minute but on occasions as little as thirty or forty seconds. This report also often had to be given whilst the commentator was already describing play on Radio 3 or, in the case of overseas matches, on some other channel. But to their admitted amazement it worked, even over the thirteen thousand miles to Australia, and it is now an everyday event.

From my first overseas tour in 1958 until I retired as a member of the staff in 1972 I was lucky enough to do seven such tours for the BBC covering MCC visits to all the Test-playing countries except India, where at that time the poor communications made live broadcasting back to Great Britain not worth the while. In addition I also commentated on two other tours not involving England. One was for ABC when Australia played the Rest of the World in 1972, and the other for SABC during South Africa’s last Test series, which they played against Australia in South Africa in 1970.

Since the mid-1960s I had shared my Test match commentaries between television and radio. Charles Max-Muller was then Head of Radio OBs and had been responsible for my being made BBC Cricket Correspondent in 1963. He rightly felt that with that title I should not just be used by television. So from 1965 up to 1969 I had been doing three Tests each season for television, and two for radio, with John Arlott and myself interchanging between the two. Though sorry to be away from television I was honoured to be allowed to join the ball-by-ball commentary teams of Test match Special, which had been going since 1957. It was quite difficult to change one’s technique from Test to Test, trying not to talk too much at one, and then having to talk non-stop at the other.

Since the war the radio commentators had included Rex Alston, Jim Swanton, John Arlott, Alan Gibson, Robert Hudson and Neil Durden-Smith. In addition there was always a visiting broadcaster from the country which was touring England. Summarisers had included Arthur Gilligan, Alf Gover, Freddie Brown and Norman Yardley. But by 1970 Rex Alston had retired and Robert Hudson had left his commentary seat for the administrative job of Head of Radio OBs – taking over from Charles Max-Muller. The 1970 set-up was to be chosen from John Arlott, Alan Gibson, Neil Durden-Smith and a visiting commentator, with Freddie Brown and Norman Yardley still the summarisers.

It was on my return from an enjoyable two months away in South Africa that I got the biggest shock of my broadcasting career. The first person I ran into on my return was Neil Durden-Smith. He said how sorry he was that I was no longer going to do the cricket commentary for television. He must have been surprised by the look of shock and bewilderment on my face, because this was the first I had heard of it. I went to see Robert Hudson – my new boss – who confirmed that he had been told of the change. He said he was sorry for me but delighted for the sake of Test match Special as he wanted me to become a regular member of that team. This kind invitation certainly softened the shock, because it was undoubtedly a blow to my pride.

I must emphasise that I have never questioned the right of BBC Television to get rid of me and I understood their reason for doing so. The commentary team of Peter West, Jim Swanton, Richie Benaud, Denis Compton and myself had become a happy group of friends who enjoyed our cricket and hoped that viewers did the same. It was natural that we probably gave an ‘amateurish’ atmosphere to the box with too many jokes and friendly asides and back-chat.

By 1970 I think BBC Television felt that they wanted a more ‘professional’ approach. No more jokes, no more camera shots of extraneous attractions like the member fast asleep or the bored blonde reading a book. They wanted the commentator to stick to the cricket only, and quite obviously the best people to do this would be ex-Test players. So the new regular commentary team became Richie Benaud and Jim Laker with Peter West remaining as linkman and interviewer. Denis Compton and Ted Dexter were the main summarisers, to be joined later by Mike Smith, Brian Close, Ray Illingworth, Tom Graveney and even Geoff Boycott when not playing. After a few seasons Denis Compton decided to drop out, feeling frustrated by the restrictions put on his natural exuberance and love of a laugh.

My transfer to Test match Special in 1970 was the start of what have been some of the happiest years of my life. TMS is a rather unique institution. In fact the BBC itself has called it a ‘new art form’. This, I have always felt, is rather overdoing it. But it is certainly a different type of broadcasting to anything that has been done before. I have to admit that it is since I joined in 1970 that it has become more different, and that I must bear some of the responsibility for this. In view of the success of TMS this may sound boastful. But in fact there is a section of listeners who disapprove of our way of broadcasting. They are, luckily for us, a minority, but we do recognise that they would prefer the old straightforward method of commentary without all the funnies and the cakes. They obviously have a case, but from the wonderful reaction which we get from so many people we feel that we are doing what the majority enjoy.

The change in TMS has been gradual but it is still founded on the original concept of providing the listener with an accurate, colourful, and lively description of a day’s cricket, bearing in mind also that cricket can be dull and does need the occasional injection of fun to maintain the listeners’ attention.

The conditions under which we work are not ideal, being often too cramped, too crowded and too hot. One would expect this to make the commentators niggly and touchy but somehow we never seem to mind. Our boxes are far better than they used to be. In the ideal box five of us can sit in a row which allows for the commentator, the summariser, Bill Frindall, the next commentator and anyone who has popped into the box for an interview.

About half an hour or so before play is due to start I usually find time to pop in and say good morning to the umpires. If one of them is Dickie Bird I tell him that the weather forecast is bad and that there will undoubtedly be some awkward and unpopular decisions to make about the light later in the day. This gets him thoroughly worried. But as he is at his happiest when the cares of the world are on his shoulders, I feel I have done some good.

During the day, however, I stay in the box for most of the time. Some go out for a breather or a gossip with friends, others who may be writing for a paper wander off to the press box. But somehow I like to stay at the scene of action in case I miss some vital piece of play. The sponsors kindly provide us with lunch boxes, though on occasions we go for a picnic with family or friends or to one of the many boxes or tents which are features of the modern Test ground. It all adds up to a marvellously relaxing day, doing something one enjoys in the company of friends. How lucky I have been to have had such convivial and compatible colleagues, and I am grateful to them all for the way they have put up with my pranks and puns.

John Arlott did more to spread the gospel of cricket than any other man alive. For thirty-four years his rich, gruff, Hampshire burr spanned the world. He took cricket into palaces, mansions, cottages, crofts, mud huts and, for all I know, igloos. He rightly became the voice of cricket and more imitated than any other commentator. Although he started his working life as a clerk in a mental hospital, followed by nine years in the police where he rose to detective-sergeant, he was basically a poet. He could do naturally what we lesser mortals had to work at – paint pictures with words. The sound of his voice alone conjured up visions of white flannels on green grass, and the smell of bat oil and new-mown grass. But his powers of description with the ever apt phrase enabled the listener to ‘see’ the scene he was describing. He always tried to imagine that he was talking to a blind person and coloured his commentary accordingly.

One of the classic commentaries of all time was his hilarious description of the Lord’s ground staff removing the covers off the square at Lord’s. They took at least twenty minutes and John never missed a trick, covering every detail of what was going on. He also gave a very fine word picture of the streaker at Lord’s in 1975. I know if I had been doing it I should have gone too far – ‘two balls going down the pitch at the same time’ – that sort of thing. But John struck exactly the right note.

He also had the enviable gift of being able to produce the apt witty comment on the spur of the moment. ‘Bill Frindall,’ he informed the listeners once, ‘has done a bit of mental arithmetic with a calculator!’ When he was with the MCC in South Africa the MCC captain, George Mann, was clean bowled by the slow left arm South African bowler ‘Tufty’ Mann. It was an unplayable ball, pitching on the leg stump and taking the off-bail. Without a moment’s hesitation John said: ‘Mann’s inhumanity to Mann!’

He had always adored cricket and with his retentive memory soon became one of the great cricket historians. How good he was as a player I am never quite sure. But he did travel round with the Hampshire team before the war, and once at Worcester actually fielded as twelfth man for them in a county match. He was also a great listener and throughout his career cultivated the company of the county cricketers all over England – wherever he was commentating. He was not afraid to ask, and so learned much about the technique and skills of the game.

He also made many friends among the first-class cricketers and this had a happy sequel when they elected him President of the Cricketers’ Association. This was a tribute and an honour and it was an office he continued to hold after his retirement from broadcasting cricket.

We all have to have our piece of luck and his chance came in 1946 when India was touring England – the first tourists since the war. After leaving the police John had become a poetry producer for the Far Eastern Service and they selected him to follow the Indians round the country, in order to send nightly reports on the matches back to India. It was soon obvious that cricket had made a find and Lobby chose him to commentate along with Rex Alston and Jim Swanton. From then until he retired he was a member of the radio commentary team at every Test played in this country.

He was a home-lover and very much a family man so he did not tour with MCC as much as Rex Alston or, later on, myself, Christopher Martin-Jenkins and Don Mosey. In fact he paid just one visit each to the three main cricketing countries, Australia, South Africa and the West Indies.

He was an emotional, kind and compassionate man, not ashamed to cry if he was affected that way – and incidentally he had more than his fair share of personal tragedy. He was also witty, much enjoyed conversation and could tell a funny story very well. This he usually did before play started after he had recovered from his exertions of climbing up to the commentary box. He always arrived hopelessly out of breath and more often than not mopping his brow with his handkerchief. He loathed the heat and several of us suffered rheumatic pains in the back through his insistence on having the commentary-box door open, so as to produce a through draught.

His commentary was in the Lobby mould, describing the action until the ball was dead and then adding a piece of ‘colour’ until the next ball was bowled. In the same way that Neville Cardus had largely created the characters of those old Yorkshire and Lancashire professionals, so John built up the physical appearance of the cricketers – deep-chested, raw-boned, broad-shouldered were frequent adjectives. He would be fascinated by trousers too tight or shirts billowing in the breeze. The umpires in their funny hats and caps were easy game for him. But he never restricted himself to just the cricket. Like I do, he saw a game of cricket as something more than whether the ball was doing this or that. He would comment on the action going on all round the ground with a slight penchant for the pigeons feeding in the outfield. It was wonderful stuff and brought the cricket match alive.

But of course broadcasting cricket was only part of his life, albeit a very important part. He was a man of many talents and an expert on books, wine, aquatints and glass. To visit his home was like going to a very hospitable museum. In his spare time he had amassed a wonderful collection of all those things he knew about and loved. His main hobby was drinking wine but over the years he put more back into his cellar than he and his friends ever drank. And that is saying a lot! I never went to his new home at Alderney after he retired but in Alresford he made use of the old cellars of the one-time pub in which he lived. It was full of every type of wine from the old, rare and priceless to the sort which you or I would keep for a very special party. If you were his guest he would remember what was your favourite wine and there would be a bottle waiting for you in front of your place at the table.

It’s no secret that in the commentary box we do have the occasional glass of champagne or wine which so many kind people send to us. In the old days this would have been unthinkable. In fact when I first joined Test match Special I had never had any such refreshment during broadcasting hours. But John gradually introduced the idea of taking a little red wine with his lunch, and then somehow lunch used to get earlier and earlier! So that is just one of the legacies which he left behind him, and now the occasional popping of a cork in the background is usually a sign of lunch or close of play approaching.

John’s cricket library was one of the largest and best private collections in the world. I say ‘was’, because before moving to Alderney he had to get rid of a lot of his books, only keeping the rarest and best. And in addition to cricket he had valuable first editions on other subjects.

Besides being such an expert collector John was a prolific writer, whether reporting cricket or commenting on wine for the Guardian or writing on average one or two books every year. It was also the accolade for any book on cricket to have a foreword by John Arlott. He must have written hundreds. It always amazed me how he could maintain this output and still find the time and energy to commentate. For many years he did his full stint of commentating and then at close of play went off to write his piece for the Guardian. But in the last five years or so he used only to do three commentary periods and finished by three o’clock, so that he could go off to the press box to write.

This would be enough for most men. But on Sundays he shared the BBC 2 Television commentary with Jim Laker on the John Player League. This would often mean travelling a hundred miles or more from the Test match, and having to be back fresh for Test match Special on Monday. One thing he told me once surprised me. He always took the first stint on BBC 2 from 2.00 to 3.00 pm. Then he would do the first stint after tea, from about 4.30 to 5.30 pm. He would then go home or back to wherever the Test match was. This meant that he had never actually seen the finish of any of the John Player matches on which he had been commentating.

At the beginning of the 1980 season John announced that it was to be his last as a Test match commentator – I remembered he had commentated on every Test played in England from 1946 onwards. He explained, ‘I’m going while people are still asking me why I’m going rather than thinking, “why doesn’t he go?’” A salutary lesson for all of us – especially for me at my time of life! In other words, although he didn’t say so, he was going out at the top. The result was a series of dinners and presentations which went on non-stop throughout the summer – everyone wanted to give him a farewell dinner – and they did! How he stood up to it I don’t know but somehow he arrived fit and well for what would be his last day – the fifth day of the Centenary Test at Lord’s.

Some unwise radio reporter tried to interview him as he arrived puffing as usual at the top of the stairs. Whilst he opened the morning session there were cameramen perched in dangerous positions filming him through the window of the commentary box. There were film lights inside the box, and rows of champagne bottles sent by admirers. It was a unique day for a unique person. We couldn’t really believe it all in the box – after 3.00 pm there would be no more John Arlott on Test match Special. He got through the morning session in his usual good form, in between opening cables and letters, and celebrating in the way he knew best. We were all dreading his final twenty-minute stint, which was due to start at 2.30 pm.

We all gathered in the box – it was packed – no one wanting to miss this historic moment in broadcasting history. The clock moved up towards 2.50 pm and as he started what was to be his last over, we all expected him to begin a series of thank yous and farewells to the listeners. But no such thing happened. He finished the over without one single mention of his departure and then when the last ball had been bowled calmly said, ‘And after Trevor Bailey it will be Christopher Martin-Jenkins.’

There was a second or two’s silence and then we all stood up and clapped. John got up and slowly left the box as Alan Curtis announced to the crowd over the public address system, ‘Ladies and gentlemen! John Arlott has just completed what will be his last ever Test match commentary for the BBC.’ The reaction was wonderful. The crowd applauded, the Australians and the two England batsmen turned round and clapped, and the members on the top balcony applauded and clapped John on the back as he threaded his way through them to disappear from sight. It was a dramatic and heart-rending display by the cricket world at the headquarters of cricket saying goodbye to an old friend who had been their favourite commentator for thirty-four years. What a triumph and what an exit. John’s timing as ever had been impeccable. And a final accolade. At the end of the season MCC made him an Honorary Life Member – and no cricketer could wish for better than that.

John retired to his lovely house in the Channel Isles where he wrote and drank with the many friends who went over there to visit him. He made the occasional foray to the mainland for broadcasts, interviews or television commercials. He still wrote on wine for the Guardian. And for the first time ever he was able to listen to the Test Match Special which he did so much to create. We miss him tremendously for his friendship and convivial companionship. The programme misses him too for his expertise, wit and unique style of commentating.

John Arlott died in December 1991. Strangely, except for one day at Old Trafford in 1989 to open the Neville Cardus stand, he never went back to a Test match. I suspect that as he listened to TMS he must sometimes have felt that Johnston had gone too far with one of his appalling puns or schoolboyish leg-pulls. If he did think so, I hope he forgave me. Because in our different ways we have both loved cricket. And he could always console himself that – unlike me – he never in all his cricketing life made a gaffe.

I have said that we are all different in the commentary box, and no one is more different than Blowers. In appearance he looks rather like a mad professor, with his horn-rimmed spectacles and long flowing hair. He normally speaks extremely fast, and this is reflected in his broadcasting. His style has been described as ‘frenetic’, and his voice certainly becomes excitable whenever the play warrants it. But there is a sense of tremendous enthusiasm in all that he says. Once, when a fielder missed an easy chance, he declared: ‘It’s a catch he’d have caught 99 times out of 1000!’ While at another Test he said: ‘He’s standing on one leg – like a horse in a dressage competition!’

The box is never dull when Blowers is on the air. His descriptions of play are blended with a collection of non sequiturs depending on what his particular fancy is at the moment. Sometimes he is ‘bus happy’, sometimes it is pigeons or any bird he can see, and he also has a penchant for butterflies.

In 1982 at the Oval there was a helicopter rally somewhere, and he caught ‘helicopteritis’. They were particularly tempting as they were flying from west to east over the Thames at the Vauxhall End, and he soon got into double figures totting up their runs. And of course at Old Trafford the trains passing through Warwick Road Station are an irresistible temptation. His ‘busitis’ was at its best (or worst!) one day at Lord’s when he religiously reported every bus passing the Nursery End in Wellington Road: ‘X comes up to bowl and the ball is played quietly to mid-off as a bus comes into sight. And as Y walks back to his mark I can see another red bus, followed by two more . . .’ And so it went on. He has such a thing about buses that at the Oval in 1982 he said, ‘Here comes a good-looking bus!’

For a countryman he is not too sure of his birds, though he usually gets the pigeons and seagulls right. But, as a listener pointed out in a letter, Henry should know that they are not pecking the outfield for worms. I suppose his classic was at Headingley one year, when he claimed to spot a butterfly walking across the pitch! I would like to add that he said that it had a slight limp, but he didn’t go that far.

I suppose he creates more amusement and giggles among ourselves in the box than any other commentator. But he takes our gentle chaffing extremely well and proceeds unruffled to describe the play, which he does with professional accuracy. Not surprising really, because he himself briefly played first-class cricket, and for many years since has travelled round the cricketing world commentating, reporting and writing on all the Test matches wherever they are played during the winter.

As a young boy he went to Sunningdale Preparatory School, where the headmaster was a friend of mine. He soon reported to me that he had a brilliant wicket-keeper called Blofeld in his first eleven. He was by far the best the school had ever had and played for four years in the eleven. From there Blowers went to Eton where he got into the first eleven at the age of fifteen, a very rare feat in such a big school. In 1957 – his third and last year – he was appointed captain. Everyone who went to play against the school came away praising the ability of Blowers behind the stumps. Here – in the opinion of Ben Barnett, the old Australian wicket-keeper – was an England player of the future. But sadly one day just before the Eton and Harrow match, he was involved in a terrible accident. He was having a bicycle race against his friend and vice-captain Edward Lane Fox, from Agars Plough to Upper Club – two playing fields at Eton. They were separated by the road to Datchet, and as Blowers – in the lead – cycled across it, he struck a Women’s Institute bus and was flung for yards down the road. He suffered appalling head injuries, and so could not play in the match at Lord’s, and his life was in the balance for some time.

But somehow he made a miraculous recovery and in 1959 went on to win a cricket blue at Cambridge as a batsman. He has played good class club cricket since then and can always be proud that he kept wicket for his native Norfolk at the age of sixteen. He could also boast – but I have never heard him do so – that he was one of only three schoolboys to make a hundred at Lord’s against the Combined Services. The other two were Peter May and Colin Cowdrey. So he was in good company. And he made it a double at Lord’s, when in 1959 he made 138 for Cambridge in their match against MCC, an innings described by Wisden as a ‘fine century’.

Blowers was a good stroke player but he never scored as fast as he talks. He gets twice as many words into a one-minute report as anyone else. And even when we have our discussions during the rain he speaks at machine-gun pace. He usually looks straight ahead of him and once he gets stuck into a subject, the words flow and it’s difficult for anyone else to get a word in edgeways – and that’s saying something in our box!

Blowers is delightful company, full of stories and anecdotes which are so full of details of time and place, that they do tend to go on a bit! Many of them are about his adventures on his trips abroad where at various times he appears to have been mugged, arrested, threatened by a cricket captain, and left standing stark naked in a hotel corridor.

In the early 1980s he became a cult with the Hillites at Sydney. Henry Blow-Fly they called him and there was even a Henry Blow-Fly Fan Club. He used to go across to the Hill to talk to them. As you will have gathered, talking plays a big part in his life, which is why he is such a good commentator and welcome member of the TMS team. His most endearing habit is the way in which he apologises for everything. No matter if it is not his fault; the box resounds with ‘Sorry, sorry’ when he is around. I firmly believe that if one accidentally shoved him off Beachy Head, he would be saying ‘Sorry, sorry’ as he fell towards the rocks below. Manners Makyth Man is the Winchester motto, not Eton’s. But it applies to Blowers.

Jenkers is the man of many voices, and his mimicry and impersonations come up to the highest professional standard. Indeed at one Lord’s Taverners’ Lunch he spoke first and produced many of his impersonations, not just of sportsmen and television personalities, but also of politicians. He brought the house down and made things very difficult for the star impersonator who had to speak after him. He can do almost anyone, even me! But he is shy about doing it in front of me, though I did once catch him taking off my rather ridiculous hyenalike laugh.

I first met him when he was still a schoolboy at Marlborough where he was two years in the first eleven. He was captain in his second year but alas Marlborough were beaten at Lord’s by Rugby, though Jenkers himself made 99, thus missing by one the chance to join his fellow commentators Blofeld and Lewis as a century-maker at Lord’s. That was in 1963, the year in which I became the BBC’s first cricket correspondent. I received a letter from him during the summer term asking for my advice on how to become a cricket commentator (I still get letters asking the same question). I asked him to come up to the BBC to meet me and, so he reminds me, I gave him lunch in the BBC Club in the old Langham Hotel. I did my best to encourage him, and told him – as I tell everyone – to get a tape-recorder and go out and describe anything and everything. Obviously a cricket match would be ideal. But the object is to say to oneself: ‘I will now talk non-stop for fifteen minutes, and imagine that I am trying to describe what I am seeing to a blind man’ (one who has gone blind, not been born blind, which makes a visual explanation more or less impossible).

He went up to Cambridge where, although he failed to get a cricket blue, he and his brother became famous for their impersonations, rather in the style of Tony Fayne and David Evans. He did, however, play for Surrey’s second eleven but with his goal still the same after five years. He wanted above everything else to be a cricket commentator. There are hundreds of young boys who have the same dream but, since there are only about ten cricket commentators who can achieve Test match status at one time, it is a more-or-less impossible dream. You must have luck, which is just what Jenkers had. In 1968 Jim Swanton appointed him Assistant Editor of the Cricketer and for two years he was able to live cricket, absorbing the atmosphere, getting to know all the players and administrators, and learning how to report and write about cricket.

It was an invaluable schooling and in 1970 he had no difficulty in getting a job in the BBC Radio Sports Department of OBs, where he continued to learn about reporting and commentating on cricket, but now as a broadcaster, and not as a writer. In 1972 I retired as a member of the BBC staff and so had to relinquish the job of cricket correspondent. After a year’s gap, Jenkers was appointed in my place and did the job for seven years, before going freelance in 1980, and becoming Editor of the Cricketer.

Those seven years were for him in some ways immensely satisfying, but in another way extremely frustrating. He went on all the tours with the MCC and broadcast commentary back to this country. In addition there came more and more demands from the News on Radio 4 and the many sports bulletins on Radio 2 for one-minute reports on the Tests and other games. Unfortunately he became so good at doing them that when he was back here in the summer he found he was being given all the reports to do, and very little commentary.

But gradually people came to realise what a good commentator he is, as well as a reporter, and he is now a fully-fledged member of the commentary team. After Don Mosey retired from the BBC staff, Jenkers took over for a second spell as BBC cricket correspondent from 1985–91, before leaving the job and the Cricketer to become cricket correspondent of the Daily Telegraph.

He is clear and articulate and to start with he had a very young voice in contrast to the more mature voices of some of his colleagues.

This should have been an advantage, but strangely in cricket – as opposed to the faster moving games like soccer and rugby – listeners tend to be a bit suspicious of youth. ‘What does he know about it? He sounds too young to know . . .’ But Jenkers overcame this because of his accurate and perceptive description of the play, and his immense background knowledge of the administrative set-up, the laws and regulations, and details of the players themselves. As Editor of the Cricketer he was at the hub of affairs and was often ‘in the know’, in contrast to someone like myself who no longer does cricket reports and news interviews.

He can also boast the slimmest figure in the commentary box. He is tall, lean and willowy with a jaunty walk and often looks as if he might be blown over by a strong wind! He is invaluable in our many discussions because he has strong views which he is happy to defend and argue about.

He is really a priceless asset to the BBC, should the latter ever wish to economise drastically. He could, on his own, carry out a day’s commentary so that the listeners would think that we were all in the box taking our turn every twenty minutes. He can imitate the summarisers as well. I really think he could get away with it, though it might be a bit exhausting.

The more I write about my colleagues the more I realise that I am on my own as a gaffe-maker. None of them seems to make the mistakes or double entendres that I do. I did however catch Jenkers once during the summer of 1982. We had been talking about a man in the crowd with a bald head. I can’t remember the reason. Anyhow, Jenkers tried to refer to him on one occasion and instead of calling him, as he intended, ‘Our bald-headed friend,’ he said, ‘Our bald-freddied hen’! Still, he has many years ahead of him and he will probably do better than that!

In spite of his slender frame he has great energy and an enormous capacity for work. On all his tours, in spite of commentating all day and doing interviews and reports at all hours of the day, he used to write a book on the tour in question, which meant that while others were relaxing after a well-earned dinner, he would be upstairs tapping away at his typewriter behind closed doors. His editorials in the Cricketer were always full of sound sense and judgement and he has been a firm advocate of the right way in which cricket should be played.

If he has a failing it could be that he tends to give our producer Peter Baxter a heart attack whenever he is due to take over commentary. He is seldom waiting in the box but hurriedly appears just as the other commentator has said, ‘Over now to Christopher Martin–.’ Oh, and one other thing I nearly forgot. Anyone who is in the box when he is commentating is advised to put cotton wool in their ears, against the moment when a batsman is out or there is some dramatic action on the field. On these occasions Jenkers’ high-pitched shout is the envy of every drill sergeant at the Guards Training Depot at Caterham!

My tendency to give people nicknames is a fairly harmless habit which I hope gives more amusement than annoyance. Even when I was in the Grenadier Guards during the war our mess sergeant became ‘Uncle Tom’, my technical clerks were ‘Honest Joe’ and ‘Burglar Bill’ – and so on. And what’s more the regular peacetime Grenadier officers so far forgot their tradition of strict discipline that they too used the nicknames. The success of a nickname depends on whether it sticks. Three of my own favourites were ‘Melon’ (for the Australian Test cricketer D. J. Colley), ‘The Hatchet’ (for an officer friend called Berry) and ‘Nymph’ (for umpire David Constant).

This brings me to The Alderman – the name with which I saddled Don Mosey some years ago. People often asked us how it came about, whilst agreeing that the title suited him well. It started when a broadcast of the Radio 2 quiz-game Treble Chance was going out from the Lancaster Town Hall. Don was organising the broadcast on behalf of BBC North Region, and he seemed to me to fit in well with all the dignified trappings of the Mayor’s Parlour and Council Chamber. So from that moment I elected him The Alderman, which he gracefully accepted ever afterwards.

He was another of our TMS team who by his character and background brought contrast to our commentaries. He lived in Morecambe and his office was in Manchester. Both in Lancashire. But forget that – he was a Yorkshireman born in Keighley, who played his first League cricket match at the age of eleven. So, incidentally, did Brian Close and they both made eleven not out on their debut. He then combined playing rugby and cricket with reporting sport for the press and could boast one performance which rivalled anyone else’s best in the commentary box. In one game he made 100 in forty-five minutes and took 7 for 28 including a hat trick. He was an opening bat and fast bowler and after the war, when he served in India, he played League cricket and in benefit matches whenever his journalistic duties allowed.

After reporting for the Daily Express and then writing on county cricket for the Daily Mail, he came to the BBC in Manchester, combining producing with broadcasting. In addition to cricket, he commentated on rugby and golf. He sometimes had the pleasure of describing the play of his son Ian, one of the country’s top golf professionals. Don had hoped that Ian would play cricket for Yorkshire, and to make sure sent his wife Jo back to Yorkshire from Nottingham three months before the birth!

Don had all the characteristics of a true Yorkshireman. This meant that he was blunt, honest, obstinate and said exactly what he thought. He tried to be a perfectionist in all he did, setting himself a very high standard. As a result he found it difficult to tolerate inefficiency in others, so that when he spoke his mind he was bound to offend some people. He saw most things in black or white, and eschewed compromise, determined to defend his principles whatever the cost. He was the complete traditionalist – Queen and Country, strict standards of behaviour and discipline, and, needless to say, orthodox three-day cricket as opposed to the limited-over competitions.

There was a perfect example of his innate traditionalism during the summer of 1982. He was an ardent devotee of the D’Oyly Carte Gilbert and Sullivan operas. With his friend Phil Sharpe at the piano he could sing his way through all the songs. When the American version of Pirates of Penzance opened at Drury Lane I saw it and thought it was a wonderful production – lively, fast-moving, with magnificent choreography and a brassy band as opposed to the rather thin orchestrations of D’Oyly Carte. It was really more of a pantomime than an opera. I implored him to go and see it if only to compare it with the traditional presentation. But he was adamant, and refused to go. It was sacrilege to interfere with something which had been such a success for so many years.

I have devoted quite a bit of space to trying to portray Don’s character, because it was all reflected in his commentary. His style was laconic and conversational with a very precise choice of words. Although during one match he announced: ‘This is David Gower’s hundredth Test. And I’ll tell you something. He’s reached his hundredth Test in fewer Tests than any other player.’

He did not flow non-stop and get too excited, as some of us do. He reported calmly what he saw, and if he approved or disapproved he would say so. Once again out came the Yorkshire honesty. If he was bored he would admit it, and would not try to build up something which didn’t exist. He had a deep knowledge of cricket based partly on his own playing experience, but even more on his close association and friendship with many of the first-class players – especially with the Yorkshire players like Brian Close, Freddie Trueman and Ray Illingworth. A rare combination of skills and tactical sense.

He toured all the Test-playing countries with one important exception – Australia, and that was probably the biggest disappointment of his life. He had gradually built up to what was to be the pinnacle of his broadcasting career. On his other tours his reports had been typically honest about the hotels, the food, the broadcasting conditions and the travel. His weekly newsletter was a model description of places visited and the goings-on of the England team. But inevitably some of his criticisms – no matter how true – offended some people. As, for instance, from India during the England tour of 1981–2 when he admittedly was not too complimentary about some of the conditions. But ironically he had been stationed in India as a soldier, and loved the country. This was evident in many of his reports but it was the words of criticism that stuck in people’s minds.

Anyhow, the BBC did not send him to Australia in 1982–3, and this was a body blow to him. Underneath the tough Yorkshire crust was an extremely sensitive and emotional man. The reason for the BBC’s decision was largely because of a change of policy in broadcasting from Australia. Previously the BBC had sent out its own commentator to join the ABC commentary team, whose output was then relayed back to England. But due to complicated contractual difficulties the BBC now had to set up their own broadcasting unit and the commentary team was made up of those already in Australia for their various newspapers and magazines, such as Henry Blofeld, Tony Lewis and Chris Martin-Jenkins. All small comfort I’m afraid for the Alderman.

Don was a terrible giggler, and the slightest thing seemed to set him off. This tempted one to play tricks on him as we did once when he was in the commentary seat and had just received a card from Peter Baxter instructing him to ‘welcome world service’. This he did and went on with his commentary. A few minutes later we put another card in front of him. ‘welcome listeners in the VIRGIN islands, and explain that their position is some considerable distance from the Isle of MAN.’ This of course had the desired effect.

Edgbaston was an unlucky ground for The Alderman. Whenever we were broadcasting from there Cyril Goodway, the chairman, kindly came along and stood in front of our box to take orders for pre-lunch drinks. He made various signs through the glass which we all understood, and he then noted down our requirements. On the first occasion Don broadcast with us at Edgbaston he knew nothing of this very civilised custom. He was on the air when Cyril appeared as usual at about 12.30. ‘Oh,’ said The Alderman. ‘I can’t see what’s going on. Some stupid idiot is making ticktack signs at me through the window. He must be crackers.’ We hurriedly wrote an explanation on a piece of paper but it was a poor return to Cyril for all his kindness over the years!

Don flattered himself on the use and derivation of words, so a few years ago I introduced him to a word game which I learned before the war in the office of our family coffee business. Don and I used to play it during intervals or sometimes when we were both resting between commentary periods. We received lots of letters asking us how it was played, and after several failures by me to explain it properly, I asked Don to devise an understandable explanation. This is it.

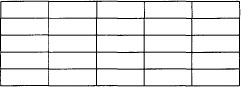

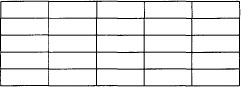

All that is required for the word game is two people, each with pencil and paper. Each draws a plan of twenty-five squares, thus:

Player A says a letter – any letter of the alphabet – and both players place that letter in any square of their choice on the plan. Player B then chooses a letter and again both players write the letter into their plan. The idea is to build up words across and down the plan. Carry on giving letters in turn until twenty-four of the twenty-five squares are filled on both plans. The final square is then filled using any letter of each individual player’s choice. Score ten for a five-letter word, five for a four-letter word, one for a three-letter word.

Any score over eighty is very, very good – over seventy very good, over sixty good, and over fifty fair. It’s actually very skilful with lots of ploys such as slipping in an x, z or q to embarrass your opponent. Try it sometime – but to save arguments, have a dictionary handy. I was always amazed that, in spite of all his knowledge of the English language, I was usually in the lead at the end of the season.

Don was appointed BBC cricket correspondent in 1984, for his final year as a member of the BBC staff before going freelance. Then in 1991 he published his autobiography The Alderman’s Tale, in which he was highly critical of what he called ‘the public schoolboy’ element on TMS. His last commentary with us was during the 1991 England v Sri Lanka Test match at Lord’s, when Jonathan Agnew made his début as a TMS commentator. But whatever may happen in the future, I hope he will always continue to send me those rude seaside postcards from Morecambe.

Bill’s is the easiest nickname to explain. He has a black beard and is undoubtedly a wonder, so ‘The Bearded Wonder’ came quite naturally. He is the vital part of the commentary machine. All we commentators are easily expendable and replaceable. But it would be hard to replace the B. W. He came into broadcasting in 1966, following the sad death of the TMS scorer Arthur Wrigley, just over a month after the end of the 1965 cricket season. He started scoring for the Temple Bar CC at the age of ten. After six years in which he began to learn about the history of cricket and its records, he then played club cricket. He is an enthusiastic tearaway fast medium in-swing bowler, and a sound batsman who bats lower than he thinks he should. He does not have much spare time during a busy summer, but on any day when he is not in the box, he will be playing cricket somewhere. He is much in demand for Sunday charity matches and organises his own tours abroad to places like Malta and Singapore. Woe betide me on the Monday of a Test match if I forget to ask him over the air how he got on in his Sunday game.

He was in the RAF for six years and then was about to start life in the City as a life assurance inspector, when he heard the news of Arthur Wrigley’s death. He had been keeping his own statistical records of first-class players for some time, and had studied the scoring methods of those three original BBC scorers (as they were called in those days), Arthur Wrigley, Roy Webber and Jack Price.

Bill has never been lacking in confidence and immediately decided to apply for the job as a replacement for Arthur. He came up to the BBC to see the cricket producer Michael Tuke-Hastings, and myself as cricket correspondent. We were struck by his confidence and obvious knowledge of cricket. But perhaps we were even more impressed by the layout and the neatness of the sample score-sheets which he brought with him. We had no doubt that he was our man and he was given a contract for the 1966 season, without our even seeing another applicant.

There must have been many people who would have liked the job, though it meant giving up the whole of the summer to scoring in the Tests and county matches. But he was prepared to take the risk, and has been the regular statistician on TMS ever since. Note the new title, which is well earned. His scoring is vitally important and he has evolved a fairly complicated format based on the original Wrigley–Webber method. It tells the commentator all he wants to know – where each stroke has gone, the exact time anything has happened, the number of balls received off each bowler, the changes in the weather, details of all the extras, delays for the ball going out of shape, the statistics of the streaker and so on.

He is usually first in the box every morning, bringing with him an amazing collection of books, pens, pencils, rubbers, calculator, a thermos, a cushion and three stopwatches. The cushion is vital because whereas we can get up and stretch our legs after our twenty-minute stints, he is stuck to his chair for the whole two-hour session. How he manages to concentrate for that length of time and do all the things he has to do against a fairly chaotic background of chatter, laughter and requests for information, I just don’t know. He can do at least three things at once, including signing autograph books which are often thrust under his nose just as he is about to record the end of an over on his elaborate score-sheet. Those three stopwatches are important too. They hang on hooks in front of him, the one on the left showing the batting time of the batsman on the left of the main scoreboard; the centre one for the overall time of the innings; and the right-hand one for the other batsman. At the start or close of play at any interval you can, if you listen carefully, hear three distinct clicks as he presses each watch as the first ball is bowled or the umpires take off the bails.

Bill can answer any question about individual cricketers, their records, results of past Test matches and so on. He carries round with him a collection of books, many of which he has compiled himself. He may not be able to answer a question immediately, but he knows exactly where to look and in a few seconds all is revealed. While he is searching for the answer he has to keep the score, and sometimes to pull his leg we ask him how many balls there are left in the over, just as he is delving into some enormous tome. After catching him out once or twice he now regularly replies ‘approximately’ two or three or whatever it may be.

But he does not just wait for us to ask him questions. The B. W. comes to each Test armed with up-to-date figures of any possible record that could be broken during that Test. His microphone is only switched up when one of us asks him a deliberate question, so when he is trying to attract attention listeners can only hear his frantic whispers in the background. He will nudge the commentator to show that he is ‘broody’ and has some priceless piece of information or sometimes he will pass a note saying something like: ‘. . . If Bloggs hits another four he will have scored more boundaries in a Test hundred than any other Englishman.’

When he does this while I am on the air I often bait him and say, ‘I’m not too sure – my memory is not very good – but I think that if Bloggs hits another four he will have scored more boundaries . . . I’ll just ask Bill Frindall to check up in his books.’ It usually succeeds in getting a rise out of him, probably displayed by a big snort. He is an inveterate snorter whenever anything amuses him, which seems to be quite often!

Trevor Bailey and Fred Trueman both retired as the expert summarisers on Test match Special at the end of the 1999 cricket season.

Trevor Bailey is the longest-serving member of the present TMS team, having made his first broadcast in 1965 and, for a change, I was not responsible for his nickname of ‘The Boil’. He acquired it when playing football for Leytonstone with his great friend and fellow Essex player Doug Insole. The crowd was largely made up of cockneys and they used to encourage him with shouts of ‘Come on, Boiley’ – hence The Boil.

For more than twenty-five years he has been one of the ‘experts’ in the box, and no one could be more qualified to that title. Captain of Dulwich College, Cambridge blue (1947–8), Secretary and Captain of Essex, and sixty-one Tests for England, achieving the rare double of 2,290 runs and 132 wickets. In addition he took thirty-two catches and was one of the finest all-rounders who ever played for England. Most people will remember him for his many back-to-the-wall defensive innings, and his famous forward defensive stroke. He liked winning but even more he loathed to lose and saved England on many occasions, the one which most people remember being the stand between him and Willie Watson at Lord’s in 1953 against Australia. So in addition to ‘The Boil’ he was also known as ‘Barnacle’ – something which sticks and is very difficult to remove.

He has become a really professional broadcaster and is one hundred per cent reliable. He can fill in at a moment’s notice, keep talking when nothing is happening, and is always ready to rescue a commentator when, as it has occasionally happened, he is incapable of speech because of laughter. The Boil’s voice has a slightly nasal drawl with a chuckle never far away. He can be sarcastic but always does his best to be on the players’ side. He knows what it is like out there in the middle. However, he does make the odd gaffe. ‘The first time you face a googly,’ he told us once, ‘you are going to be in trouble if you’ve never faced one before’!

He is a severe critic of bad tactics, bad behaviour and bad cricket. As a player he was always a shrewd tactician with an inside knowledge of his opponents’ weaknesses. He speaks his mind about what he thinks are captains’ mistakes, and always deplores a player reacting badly to an umpire’s decision, or gesticulating or swearing at an opponent.

This is not to say that he himself was not above a bit of gamesmanship, which is very different to cheating. For instance he would have no hesitation in bowling down the leg-side as he did to save the game at Headingley against Australia in 1953. He himself has defined bad cricket as ‘a night-watchman trying to hit a six, a seam bowler who fails to bowl a reasonable line and length, or a very late call which leaves the other batsman stranded in the middle of the pitch . . .’

He tends to talk in short staccato sentences like Mr Jingle in The Pickwick Papers which has given him yet another nickname in the box – Mr Jingle. He will say: ‘Fine bowler. Good line and length – moves it either way – never tires – good cricketer – like him in my side.’ He also, like all of us, has his favourite adjective or adverb. His is ‘literally’, and he has been logged as saying: ‘His tail is literally up’; ‘. . . it’s a tense moment for Parker who is literally fighting for a place on an overcrowded plane to India’; ‘Tavaré has literally dropped anchor.’

On a tour or in the box he is a splendid companion, who enjoys a party more than most. He has a delightful, slightly cynical sense of humour and sometimes in triumph comes out with an even worse pun than any of mine. He is also a good feed for some of the jokes we make in the box. I remember once asking him, ‘What do you call a Frenchman who is shot out of a cannon?’ He repeated the question in full as every music-hall straight man always did: ‘I don’t know, what do you call . . . etc.’ I was then able to answer: ‘Napoleon Blownaparte,’ at which he broke with tradition and laughed.

He is a joy to work with because you know he will never let you down or be lost for something to say. His broadcasting is like his batting – safe, reliable, unhurried, provocative at times, and gives the listener a sense of security. With him in the box we have the feeling that we cannot lose.

Life in the commentary box has never been the same since Freddie Trueman joined The Boil as our other regular expert summariser. He is outsize in everything – his figure, his personality, his pipe and his stories. Like another great Yorkshireman, Sir Harold Wilson, Fred has an astonishing memory. His knowledge of cricket, its records and its players is phenomenal. He and I do our best to stump each other with quiz questions. I am easy meat but I can very rarely catch him out. He played his cricket with such astute tacticians and technicians as Hutton, Illingworth and Close and he has obviously stored everything he saw or heard in his ‘little grey cells’. He might in fact have made a great captain, and can at least be proud of his achievement in 1968. In the absence of Brian Close he captained Yorkshire against the Australians at Sheffield and Yorkshire beat them for the first time since 1902 by an innings and sixty-nine runs.

Fred is down-to-earth in everything he says and I must say is extremely fair. He will praise or criticise as the occasion warrants and express himself strongly in either case. During one Test match he declared: ‘Anyone foolish enough to predict the outcome of this match is a fool!’

He is undoubtedly a bit puzzled by some of the modern cricket tactics and has a favourite phrase: ‘I don’t know what’s going off out there.’ And I must admit that I often agree with him! He is at his most critical about the modern fast bowlers, particularly as regards their actions and their fitness. Inevitably it may seem to some listeners that he is looking at the past through rose-coloured spectacles. But if anyone is honest – as of course every Yorkshireman is – he or she must agree that the standard of play in first-class cricket has dropped, except for fielding, throwing and running between the wickets.

Fred, as you can imagine, is never lost for words or the apt phrase and his sense of humour comes through in all he says. He also enjoys the simple jokes that are often sent in to us:

Brian: If you were stark naked out in a snowstorm, what animal would you like to be, Fred?

Fred: I dunno, Johnners, let’s have it.

Brian: A little otter.

or

Brian: Who was the ice-cream man in the Bible?

Fred: All right. I’ll buy it.

Brian: Walls of Jericho.

After I had told this joke a listener wrote in to me and asked, ‘What about Lyons of Judah?’

Fred undoubtedly adds great weight to our commentary team. He can speak with the confidence of a man who took 307 Test wickets. He brings a strong northern flavour to contrast with the more southerly tones and attitudes of all of us in the box, except for Don Mosey. I know that Fred loves every minute of his time with us. We enjoy having him too and value all his cricketing knowledge and experience, although we are never quite sure what he is coming out with next. Of one thing, though, we can be sure. He will always be creating a smoke-screen with his vast pipe or Lew Grade cigars. The resulting smell is pretty pungent, so we call Fred’s cigars ‘Adam and Eve’ – every time he’s Adam, we Eve! But it is a small price to pay, and he wouldn’t be Fred without them. I am sure that after reading this book some of you will say, ‘Oh, he hasn’t mentioned so-and-so.’ And you will be quite right. I have only written about other commentators with whom I have had the pleasure of working in OBs. Ever since I left the BBC in 1972 there has been a steady influx of new commentators, especially in the worlds of soccer, rugby and athletics. I have met and worked with many of them in various sports programmes but not on an outside broadcast, as I have really only been concerned with cricket and the Boat Race, as far as sports commentary is concerned.

I would like to wish all those commentators – as well as the ones whom I have mentioned – as much happiness, fun, enjoyment and job satisfaction as I have had during my broadcasting life. Commentators are a unique band. There are very few of us, and in spite of the travel, long hours, the stresses and the working conditions – often too cramped, too hot or too cold – we should all be extremely grateful for having such a wonderful job. People do sometimes complain, forgetting how lucky they are and that there are so many millions of people far worse off than themselves. Perhaps this story will remind them.

There was a young parachutist about to make his first jump from an aeroplane, and he was naturally very nervous and scared. His instructor tried to calm him down and told him that there was nothing to worry about.

‘Just remember,’ he said, ‘when I give you a push count five and then pull the top ring on your parachute. If, by any chance, nothing happens, don’t panic. Just count another five, and then pull the bottom ring. This will open your reserve parachute, and you will sail gracefully down to earth. Nothing to worry about at all.’

The learner was still shivering with fright but when they were at the right height and place, the instructor told him, ‘Right, I am going to push you out now. Don’t forget. Count five – top ring – count another five – bottom ring. And whatever you do, don’t panic. Off you go. Good luck.’

With that, he pushed the learner out of the plane. The young man remembered what he had been told. He counted five, pulled the top ring and waited for something to happen. Nothing did. So again he remembered what he had been told. He counted another five and confidently pulled the bottom ring. But again – this time to his horror – nothing happened. His pace increased and he was dropping at an alarming rate down to earth, when he suddenly spotted someone coming up towards him. It was a man in a peak cap and overalls, carrying a large spanner.

The parachutist – now in a complete state of panic – shouted at this man as he shot upwards towards him:

‘Help! Help! Do you know anything about parachutes?’

‘No, I’m afraid I don’t,’ replied the man in the peak cap as he shot past him. ‘And what’s more, I obviously know bugger all about gas boilers!’