Daniel L. Carter

Robert A. Prentky

Ann W. Burgess

The past decade has seen considerable advances made in (1) raising consciousness about sexual violence, (2) developing victim services, (3) apprehending suspects, (4) convicting suspects, and (5) empirical research on sexually aggressive behavior. Indeed, Chappel and Fogarty (1978) referred to publicity about rape within the last decade as a“veritable explosion.” This publicity, and, by inference, an attendant increase in social awareness, has led to noteworthy advances in the development and provision of victim services (McCombie 1980), rape law reform (e.g., Marsh, Geist & Caplan 1982), and research on the sexual victimization of women (e.g., Walker & Brodsky 1976; Holmstrom & Burgess 1978; Chapman & Gates 1978; Russell & Howell 1984).

Also, the past decade has observed a steady increase in the numbers of reported rapes and a parallel acknowledged fear of rape (Warr 1985). Studying fear of rape among 181 urban women using a mail survey in 1981 revealed that two-thirds of the women under age thirty-five ranked fear of rape on the top half of the scale. Warr’s (1985) data suggest the majority of women will experience moderate to high levels of fear of rape through adolescence to mid-thirties. He contends fear of rape continues to be a problem of considerable magnitude and consequence. Russell and Howell (1984) conclude from their San Francisco interview survey that sexual violence against women is endemic.

However, one area that has remained embedded in controversy is advice about how to deal with dangerous human situations. There has been a great deal of debate over what a person should do when confronted by an assailant. The literature suggests two polarized views of what to do when confronted with a rapist: ( 1 ) acquiesce, or do not resist, and (2) resist and/or fight. We wish to bridge this polarization by reviewing the victim resistance data from our sexual homicide study and from a study of convicted rapists. The data analysis from surviving rape victims assists in defining strategies according to type of assailant.

* Reprinted, with changes and permission, from Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1 (1) 1986: 73-98.

We analyzed from our study of sexual homicide the offenders’ perceptions of victim response to their attacks as a way to add to the data base on victim resistance.

Victims of Thirty-Six Sexual Murderers

There were 118 victims in this study; 109 were fatally injured and nine survived the murder attempt. Most victims in this sample were white (92 percent), female (82 percent), and not married (80 percent). The age ranged from six to seventy-three for 113 victims (five cases provided no victim age). Fourteen, or 12 percent, were fourteen or younger; eighty-three, or 73 percent, were between fifteen and twenty-eight years old; and sixteen, or 14 percent, were thirty years or older. Thus, most victims (73 percent) were between fifteen and twenty-eight, which matches the age range for rape victims in general.

Close to half (47 percent) of the victims were closely related in age to the offender. More than one-third of the cases (37 percent) involved a younger victim than offender. In 15 percent of the cases, the victim was older than the offender. More than half of the victims came from average or advantaged socioeconomic levels (62 percent), 30 percent had marginal incomes, and 9 percent had less-than-marginal incomes.

In more than one-third of the cases, the victim had a companion at the time of the assault, with 63 percent being alone at the time of the murder.

Victim Resistance

Any cause-effect determination in victim resistance reports needs to include the total series of interactions between a victim and an assailant, including the dynamic sequencing of victim resistance and offender attack. Offenders were asked to report on their victims’ resistance in terms of whether they tried to verbally negotiate, verbally refuse, scream, flee, or fight. The offender was then asked to report his own response to the victim’s behavior. It is important to keep in mind that these data represent only the offender’s perceptions of the victim-offender interaction.

In the eighty-three cases with data, twenty-three victims (28 percent) acquiesced or offered no resistance as perceived by the offender. One murderer said, “She was compliant. I showed her the gun. She dropped her purse and kind of wobbled a second and got her balance and said,‘All right; I’m not going to say anything. Just don’t hurt me.’” Twenty-six (31 percent) victims tried verbal negotiation; six (7 percent) tried to refuse verbally; eight (10 percent) screamed; four (5 percent) tried to escape and sixteen (19 percent) tried to fight the offender.

The reaction by the offender to the victim’s resistance showed that while in thirty-one cases the offenders (34 percent) had no reaction, fourteen (15 percent) threatened the victim verbally, twenty-three (25 percent) increased their aggression, and twenty-four (25 percent) became violent. Thus, in two-thirds of the cases, the assailant countered the victim’s resistance; often (50 percent) it was met with increased force and aggression. Thus it appears with most offenders interviewed, both physical and verbal (or forceful and nonforceful) resistance played a part in triggering a reaction by the offenders.

It is important to note that almost equal numbers of victims in the homicide sample were said to have resisted physically (N = 25) as were said to have made no attempt at resistance (n = 23). Both types of victim actions resulted in death.

The FBI special agents interviewed the murderers about deterrence to killing. Murderers who were not consciously aware of their motives to kill were the only ones able to identify factors that might deter their killing. They stated such prevention factors as being in a populated location, having witnesses in the area, or cooperation from the victim. Those murderers who had a conscious plan to kill said that factors such as witnesses and location did not matter because the murder fantasy was so well rehearsed that everything was controlled (“I always killed in my home, and there were no witnesses.”). Or as one murderer said,“The victim did not have a choice. Killing was part of my fantasy.” Also, the murderer with the planned fantasy generally believed he would never be caught.

A study was conducted on data from 108 convicted rapists committed to a treatment center and 389 of their victims. The study examined the amount of expressive aggression before, during, and after the offense specifically by rapist type. The Massachusetts Treatment Center rapist classification system is concerned with the interaction of sexual and aggressive motivation. Although all rape clearly includes both motivations, for some rapists the need to humiliate and injure through aggression is the most salient feature of the offense, whereas for others the need to achieve sexual dominance is the most salient feature of the offense. In abbreviated fashion, four of the subcategories of rapists follow.

For the compensatory rapist, the assault is primarily an expression of his rape fantasies. There is usually a history of sexual preoccupation typified by the living out or fantasizing of a variety of perversions, including bizarre masturbatory practices, voyeurism, exhibitionism, obscene telephone calls, cross-dressing, and fetishism. There is often high sexual arousal accompanied by a loss of self-control, causing a distorted perception of the victim/offender relationship (for example, the rapist may want the victim to respond in a sexual or erotic manner and may try to make a“date” after the assault). The core of his fantasy is that the victim will enjoy the experience and perhaps even“fall in love” with him. The motivation derives from the rapist’s belief that he is so inadequate that no woman in her right mind would voluntarily have sex with him. In sum, this is an individual who is“compensating” for his acutely felt inadequacies as a male.

For the exploitative rapist, sexual behavior is expressed as an impulsive predatory act. The sexual component is less integrated in fantasy life and has far less psychologic meaning to the offender. That is, the rape is an impulsive act determined more by situation and context than by conscious fantasy. The assailant can best be described and understood as a man“on the prowl” for a woman to exploit sexually. The offender’s intent is to force the victim to submit sexually, and hence, he is not concerned about the victim’s welfare.

For the displaced rapist, sexual behavior is an expression of anger and rage. Sexuality is in the service of a primary aggressive aim, with the victim representing, in a displaced fashion, the hated individual(s). Although the offense may reflect a cumulative series of experienced or imagined insults from many people, such as family members, wife, girlfriends, it is important to note that there need not be any historical truth to these perceived injustices. This individual is a misogynist; hence, the aggression may span a wide range from verbal abuse to brutal murder.

For the sadistic rapist, sexual behavior is an expression of sexual-aggressive (sadistic) fantasies. It appears as if there is a fusion (i.e., no differentiation) or synergism between sexual and aggressive feelings. As sexual arousal increases, aggressive feelings increase; simultaneously, increases in aggressive feelings heighten sexual arousal. Anger is not always apparent, particularly at the outset, wherein the assault may actually begin as a seduction. The anger may begin to emerge as the offender becomes sexually aroused, often resulting in the most bizarre and intense forms of sexual-aggressive violence. Unlike the displaced anger rapist, the sadist’s violence is usually directed at parts of the body having sexual significance (breasts, anus, buttocks, genitals, mouth).

Study Findings

The results of data analysis indicated that for all rapist types, there was a higher incidence of brutal aggression associated with combative resistance than with noncombative resistance. Of the four rapist types, there were important differences in victim resistance and physical injury and amount of expressive aggression before, during, and after the sexual act, thus implying the need to adjust a resistance strategy to the type of rapist encountered. This chapter defines the four types of rapists and outlines a strategy derived from the analyzed data.

While we cannot infer causality from the correlative data analyzed (i.e., it cannot be ascertained whether a victim’s combative response precipitated or contributed to an increase in violence or was a reaction to violence), the data strongly suggest that it is important to explore strategies that are viable alternatives to physical combativeness, particularly in situations where such resistance proves to be ineffective and may increase the risk of serious injury or even death. Knowledge of alternative strategies may serve to enhance the effectiveness of resistance.

The following discussion is an attempt to provide an overview of possible strategies for resisting rape. The observations and conclusions derive from our joint clinical experience, including extensive contact with victims and offenders as well as the detailed evaluation of more than three hundred offender files. This experience allows us to observe a large number of effective and ineffective responses to rape, sometimes with the same offender. While there is a conceptual and clinical foundation for the recommendations that follow, there is, at present, little supportive empirical evidence.

Studies have examined coping behaviors of victims (e.g., Burgess and Holmstrom 1976, 1979), strategies of rape avoiders and rape victims (e.g., Bart and O’Brien 1984) and victim behavior signaling vulnerability (e.g., Grayson and Stein 1981). Analysis of the various strategies defined in the literature, combined with our clinical experience with both convicted offenders and rape victims, allows us to define a typology of response strategies as follows: escape, verbally confrontative resistance, physically confrontative resistance, nonconfrontative verbal response, nonconfrontative physical resistance, and acquiescence.

Escape

We emphasize that escaping the assailant is always the optimum response when it can be employed successfully. However, deciding whether an escape attempt will be successful is very difficult. If the victim is alone in the woods with nowhere to run or is assaulted by multiple offenders, escape attempts may not only be unsuccessful, but may also be hazardous. If weapons have been brandished, the possible consequences of attempting to escape—and being caught—may make it not worth the risk. If the offender appears to be young and athletic, the probability of a successful escape diminishes.

In general, in a city or urban location, if there are no weapons, if there are other people somewhere in the vicinity, and if there are no encumbrances (i.e., no clothes tied or tangled around the ankles), the probability of successful flight will be increased. Caution must be exercised, however. There is a small percent of individuals (i.e., sadists) for whom unsuccessful flight may only serve to increase arousal and, in so doing, increase the brutality of the attack.

Verbally Confrontative Resistance

This strategy includes screaming or yelling (“Leave me alone! Get away!”) as a means of attracting attention or asserting oneself against victimization. These verbal responses are strictly confrontative and are intended to convey the message at the outset of the assault that the victim will not acquiesce.

Physically Confrontative Resistance

Confrontative physical resistance ranges from moderate responses (fighting, struggling, punching, or kicking) to violent responses (attacking highly vulnerable areas—face, throat, groin—with lethal intention). These responses are dictated by many critical situational factors, such as the location of the assault, the presence of a weapon, the likelihood of help, the size and strength of the offender, and the degree of violence of the assault. When employed successfully, such responses often occur quickly and make use of surprise. The victim can expect that in many cases physical resistance will be met with increased aggression.

Nonconfrontative Verbal Responses

These responses are intended to dissuade the attacker (“I’m a virgin,” or“I have my period or cramps.”), create empathy (engaging the offender in conversation and listening and attempting to respond in an understanding way), inject reality (“I am frightened.”) or negotiate (“Let’s talk about this,” or “Let’s go have a beer.”) to stall for time and devise another strategy (set the stage for an escape). Talking tends to be the safest and most reliable means of reducing the degree of violence (once it is determined that the offender is intending to use violence), though it may not be effective in stopping the assault completely.

In general, nonconfrontative dissuasive techniques do not work (McIntyre 1978). In the heat of an attack, most rapists will not be concerned about the victim’s menstrual cramps or virginity if, in fact, they even believe her. Victims should avoid such references as“I have VD” or“I’m pregnant,” as such statements may support the offender’s pathological fantasy that the victim is “bad” or promiscuous and thus deserves to be raped. Also threats of reprisal (“You will be caught and go to jail.”) should be avoided.

The safest way to engage the assailant through dialogue is for the victim to appeal to his humanity by making herself a real person and by focusing on the immediate situation (“I’m a total stranger. Why do you want to hurt me? I’ve never done anything to hurt you,” or“What if I were someone you cared about? How would you feel about that?” and not“This is going to ruin my life.”). The attacker can easily dismiss what may happen sometime in the future. He cannot as easily dismiss what the victim is telling him is happening right now. The victim should avoid asking“What if I were your daughter or sister?” because she will not know what meaning such an individual has for the offender.

Nonconfrontative Physical Resistance

This technique involves active resistance that does not actually confront the attacker (as in the case of physical confrontation). Nonconfrontative physical responses may be feigned or quite real and uncontrollable. Feigned responses might include fainting, gagging, sickness or seizure. Uncontrollable or involuntary responses may include crying, gagging, nausea, and loss of sphincter control. In general, these responses may work on occasion, but they are highly idiosyncratic and thus are not reliable. In one important situation (with a displaced-anger rapist), this strategy could be dangerous.

Acquiescence

Acquiescence implies no counteractive response (offensive or defensive) to thwart the attack. The victim might say something to the effect of“Don’t hurt me and I’ll do what you want.” Acquiescence is often the result of paralyzing fear, abject terror, or a belief that such a response is necessary to save one’s life. In most cases, acquiescence need only be a last resort when attempts to stop the attack have failed. Acquiescence may be interpreted by the offender as participation and exacerbate the intensity of the attack.

In general, the decision to submit or acquiesce to an attacker is a difficult one, determined as much by the violence of the assault as by the victim’s emotional state and specific fears (such as death or rape). Some women will be able to cope much better than others with the knowledge that they submitted. Acquiescence can invoke, in some victims, postassault rage and/or guilt, while other victims may be able to accept and feel comfortable with whatever actions they felt were necessary to survive the assault with a minimum of physical and emotional injury. If, after other strategies have failed, acquiescence is deemed to be the optimum response to protect life and reduce physical injury in a given situation, it is important that the victim be comfortable with such a choice and be aware that postassault guilt feelings will probably arise.

We operate on the assumption that aggression begets aggression. When the amount of rage and aggression obviously exceed what is necessary to force compliance, a violent confrontative response on the part of the victim will generally increase the violence in the assault and place the victim at increased risk for serious physical injury. Gratuitous violence on the part of the rapist places the victim in dangerous, volatile, and unpredictable situations. For that reason, we recommend that the first response to violence not be violent. If direct dialogue does not begin to neutralize the attacker (reduce the intensity of the aggression), then the victim will have no recourse but to employ any means available to object. The offender believes that he is entitled to sex under any condition, and hence has a callous indifference to the comfort or welfare of the victim. Both verbal resistance and nonconfrontative resistance strategies are appropriate. Once it has been demonstrated that the rapist will likely use whatever force necessary to gain victim compliance, confrontative physical resistance would be unwise unless the victim is confident that it will work. The best strategy, then, is to encourage the rapist to start talking about himself (playing on his narcissism) so that the victim becomes real rather than a sexualized object. Nonconfrontative physical strategies may also work, but they tend to be unreliable and are highly idiosyncratic to the individual rapist. As noted earlier, some of these responses (crying, nausea, gagging) may be involuntary, in which case the victim may have to overcome the response if it is aggravating the situation.

Many exploitative rapists will certainly be given a moment’s pause if the victim appears undaunted and immediately says,“You what? Here? Now? Come on, let’s sit down here and talk.” While admittedly this requires extraordinary presence of mind on the part of the victim, it has the advantage of momentarily catching the rapist off guard. It may not avoid the rape, but it might decrease the amount of physical injury that could result from the assault as well as give the victim time to assess options and set the stage for possible escape.

If the victim is unable to engage the offender in conversation, and the physical attack continues, escalates, or appears to be lethal, the victim should fight with every means available (attack eyes or groin, hit the offender with a rock or stick, etc.) to escape and/or avoid serious injury.

If the assailant remains after verbal confrontation, has no weapon, and responds with threats or retorts, the victim should immediately resist physically by punching, hitting, kicking. Such physically confrontative resistance is often successful with compensatory rapists and is sometimes successful with exploitative rapists.

If the attacker responds to victim physical confrontation with increased anger and/or violence, the victim should cease physical resistance. If he responds by immediately ceasing his aggressive/violent behavior and is willing to engage the victim in conversation, he is also likely to be an exploitative rapist and the victim should use verbal strategies.

If the attacker continues to escalate aggression/violence, the victim should attempt to begin verbal dissuasive techniques. Again, the object is to break the confrontation, reduce tension, and defuse the violence. If verbal dissuasion is unsuccessful and the violence continues in spite of the victim’s attempts, the victim again must do anything to get out of the situation. If verbal dissuasion is successful and the violence seems to diminish, those same responses should be continued, with specific statements tailored to what the rapist is saying.

For the displaced-anger rapist, the victim is a substitute for and a symbol of the hated person(s) in his life. The primary motive is to hurt and injure the victim. Aggression may span a wide range from verbal abuse to brutal assault. Continued physical confrontation, unless the victim is reasonably certain that she will be able to incapacitate the attacker, may only justify in the offender’s mind the need to“punish” the victim and thus escalate the violence.

In general, nonconfrontative responses are also not recommended. A displaced-anger rapist will not respond empathically to the victim’s evident pain or discomfort. Such responses as nausea, gagging, or crying are evidence that the rapist is achieving the desired result. Moreover, acquiescence is not an appropriate response to this type of rapist. Because sexual intercourse is not this offender’s primary motive, deterrence of the rape will not be accomplished by acquiescing.

The recommended response to such a rapist is verbal, and the words must be carefully chosen. The victim must convince the offender that she is not the hated person (“It sounds like you’re really angry at someone, but it can’t be me. We’ve never even met before.”). The victim should avoid statements that may justify the assault in the mind of the rapist. Challenging the fantasy is critical. Statements such as“How do you know that I’m a bitch? You’ve never met me before. We’re strangers. I could be a nice person,” may be along the lines of what is appropriate.

For the sadistic rapist, the victim is a partner who has been recruited to play out sexual-aggressive or sadistic fantasies. Needless to say, this rapist is an extremely dangerous individual. Because these assaults are brutal and can end with serious physical injury to the victim, it may be a matter of life and death to escape.

If escape is not possible, there are few recommendations we can make. If the victim acquiesces, the sadistic offender may perceive her as an active participant in the assault. This will function to increase his arousal, and hence, his anger. If the victim is physically confrontative, struggles, or otherwise seeks to protect herself, the rapist may also perceive her as an active participant, which also will increase his anger and arousal. Passivity or submission may also serve to intensify feelings of rage in the offender. Once the fused sexual-aggressive feelings are activated, sadists generally will not hear attempts at negotiation, empathy, or dissuasion. Finally, nonconfrontative physical resistance is not effective, as there is a high probability that these behaviors may also be interpreted as participation in the assault.

Because there are no reliably safe and effective responses, the victim must do anything necessary to get out of the situation. That may mean feigning participation and, at a critical moment, making maximum use of surprise, attacking the offender’s vulnerable areas as viciously as possible. This requires the victim to convert fear into rage and a sense of helplessness into a battle for survival.

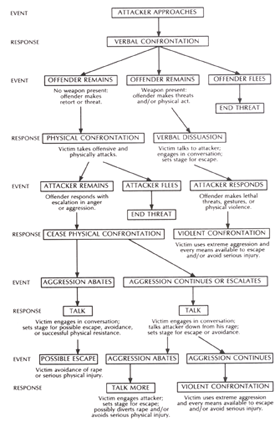

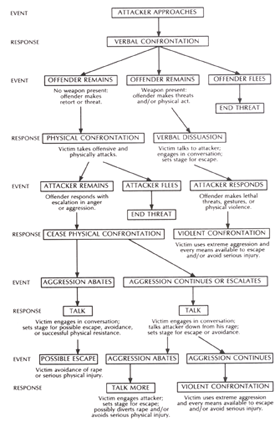

We realize that most of our recommendations may be forgotten at the moment of panic when the victim is confronted by a would-be rapist. The victim may not have the presence of mind—and perhaps not even the time—to evaluate different responses to rapist types. Believing, however, that knowledge brings an added sense of confidence to an unpredictable and volatile situation, we have tried to reduce much of the foregoing discussion to a systematic decision-making process (see figure 14-1).

The first response should always be to attempt to escape. If escape is not possible, the second response is firm verbal confrontation. If the attacker persists, there is no weapon present, and no physical violence is occurring, the victim should immediately initiate the third response: offensive physical confrontation. If the attacker flees, he probably is compensatory. If he does not flee and responds with physical aggression, the victim should start talking, keeping conversation in the present. The victim should attempt to reduce the aggression, talk the assailant down from his rage, and convey the message that she is a stranger, and that there are other ways to find a sex partner or express anger. The intent is to disrupt the fantasy and, in so doing, challenge the rapist’s symbolic conceptualization of the victim.

Figure 14-1. Victim Response Strategies

If the response is positive (the offender stops, listens, or talks), the same course of action should be continued. If he pays no attention and persists in his attempts to force the victim to submit to sexual activity and if the amount of aggression does not extend beyond that force, the attacker is probably exploitative. The victim should persist in verbal attempts to make herself real by diverting the offender with questions about himself.

If there is a clear escalation in aggression, the victim should try to distinguish between a displaced and a sadistic motive. If the primary intent seems to be to humiliate and demean by word or deed, the offender is more likely to be a displaced-anger rapist. If none of this is present, and the rapist is making demands that are both eroticized and bizarre, then he is probably sadistic. With a displaced-anger rapist, the victim should keep conversation in the here and now and underscore the message that she has not abused him. Because these men have a history of perceived abuse by women, the victim should try to demonstrate some sense of interest, concern, or caring. If the victim determines that the individual is a sadist, she should use extreme violent confrontation and do whatever possible to escape. There is no single response that is likely to deter a sadistic assault, and because these assaults are potentially lethal, the victim must do whatever is in her power to survive the attack and attract help.

We have been discussing in the abstract what to do in a highly traumatic situation, and it may seem cavalier or even insensitive to suggest that a victim should perform a quick mental status exam as she is being assaulted. However, all rapes are not“blitz” assaults, and victims have often been noted to use multiple strategies over time until one works (Bart and O’Brien 1984). As an overview, as well as an attempt at simplification, the strategies that we have recommended can be briefly summarized as follows:

Step 1. Firm verbal confrontation. Firmly tell the attacker to get away and leave you alone.

If step 1 is unsuccessful:

Step 2. Physical confrontation. Immediately take the offensive and attack the assaulter with moderate physical aggression (hit, kick, punch, etc.).

If step 2 is unsuccessful:

Step 3 : Nonconfrontative Verbal Responses. Attempt to calm the assaulter and talk him down from his rage. Engage him in conversation, and make yourself a real person to him. Challenge his fantasy that you are the person he wants to harm. Set the stage for an escape attempt (e.g., try to talk him into taking you to a more populated area:“Let’s go have a drink” etc.).

If step 3 is unsuccessful in neutralizing the violence:

Step 4: Violent confrontation. Use extreme aggression, and take any action within your means (kick, punch, bite, strike with rock, etc.) to incapacitate the assaulter and avoid rape or mortal physical injury.

In sum, knowledge may be the only weapon a victim has in a highly dangerous situation. As such, knowledge can provide a sense of power, as well as the confidence necessary to act rather than resign out of helplessness.

Notes

Bart, P.B., and O’Brien, P. Stopping rape: Effective avoidance strategies. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 1984, 10, 83-101.

Burgess, A.W., and Holmstrom, L.L. Coping behavior of the rape victim. American Journal of Psychiatry, 1976, 113: 413-418.

Burgess, A.W., and Holmstrom, L.L. Adaptive strategies and recovery from rape. American Journal of Psychiatry, 1979, 136: 1278-1282.

Chapman, J.R., and Gates, M. (Eds.) The Victimization of Women. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, 1978.

Chappell, D., and Fogarty, F. Forcible rape: A literature review and annotated bibliography. National Institute of Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice, Law Enforcement Assistance Administration, U.S. Department of Justice. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1978.

Grayson, R., and Stein, M.I. Attracting assault: Victims’ nonverbal cues. Journal of Communication, 1981, 31: 68-75.

Holmstrom, L.L., and Burgess, A.W. The Victim of Rape: Institutional Response. New York: Wiley, 1978.

Marsh, J.C., Geist, A., and Caplan, N. Rape and limits of law reform. Boston: Auburn House Publishing Company, 1982.

McIntyre, J.J. Victim response to rape: Alternative outcomes. Final Report to the National Institute of Mental Health, Grant #R01 MH29045,1978.

McCombie, S.L. (Ed.) The rape crisis intervention handbook: A guide for victim care. New York: Plenum, 1980.

Russell, D.E.H., and Howell, N. The prevalence of rape in the United States revisited. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 1983, 84.

Walker, M.J., and Brodsky, S.L. Sexual assault, Lexington, Mass. DC Heath and Co., 1976.

Warr, M. Fear of rape among urban women. Social Problems, 1985,32: 238-250.