Building Better Boards

by David A. Nadler

IN BUSINESS, AS IN FAMILIES, overly permissive parenting is often blamed for egregious misbehavior. Recent scandals have exposed some boards as too passive, too indulgent, or flat-out oblivious to what goes on around them. As a result, companies facing new governance requirements are scrambling to buttress financial reporting, overhaul board structures—whatever it takes to become compliant. If they stop there, though, compliant is all they’ll be. That would be a shame.

The key to better corporate governance lies in the working relationships between boards and managers, in the social dynamics of board interaction, and in the competence, integrity, and constructive involvement of individual directors. Patently, this is not the stuff of legislation. In fact, as others have noted (“What Makes Great Boards Great,” Jeffrey A. Sonnenfeld, HBR, September 2002), many corporate scofflaws already had in place the “reforms” now prescribed as a vaccine against misconduct. Boards dissatisfied with lowest-common-denominator improvements cannot count on answers imposed from outside. Instead, they must think aspirationally and act practically, deciding where they want to go and then equipping themselves for the journey.

That journey will probably be a long one. Everyone knows what most boards have been: gentleman’s-club-era relics characterized by ceremony and conformity. And everyone knows what boards should be: seats of challenge and inquiry that add value without meddling and make CEOs more effective but not all-powerful. A board can reach that destination only if it functions as a team, as we have come to understand teams over the past few decades.

The high-performance board, like the high-performance team, is competent, coordinated, collegial, and focused on an unambiguous goal. Such entities do not simply evolve; they must be constructed to an exacting blueprint. At Mercer Delta, we call that act “board building.”

The challenge of board building is huge; most companies don’t know where to begin. To help them, we’ve developed an agenda and a set of tools that boards can use to define and achieve their objectives. The following guidance derives from our recent work with the CEOs and directors of more than two dozen major companies on the topics of board effectiveness, governance reforms, and CEO performance appraisal and succession.

We also collaborated with the Center for Effective Organizations at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles to survey more than 300 chiefly independent directors representing the boards of more than 200 large corporations. In general, the results of our survey mirrored our firsthand observations. One point that emerged repeatedly was the importance of regular self-assessment when building a strong board.

The Right Mind-Set

Board building is an ongoing activity, a process of continuous improvement, which means boards must keep coming back to the same questions about purpose, resources, and effectiveness. The best mechanisms for doing that are annual self-assessments. According to our survey, conducting and acting on such assessments are among the top activities most likely to improve board performance overall.

Of course, not everyone does what they know is best for them. Only 56% of respondents to our survey said their boards’ performance is formally evaluated on a regular basis. And only one-quarter of those—or 16% of the entire sample—have a plan to address the concerns raised by their assessments. Clearly, many boards lack data from which to draw conclusions about their success and processes for using the data they do have to improve.

But to assess or not to assess isn’t really the question: The New York Stock Exchange now requires annual board evaluations. Companies do retain great flexibility around what to assess and how, as well as how to apply the results. Some boards skate by with paper-and-pencil surveys comprising recycled checklists cobbled together by another company’s attorneys. That will keep them listed, but it won’t do much to improve their minimalist approach to governance.

Others treat self-assessment as a transformational exercise. The boards of Medtronic, Service Corporation International, Bank of Montreal, and Best Western, among others, have self-assessed themselves into high-performance teams, rethinking members’ roles and working relationships. Such extensive reinvention requires serious time and energy—scarce commodities for directors and CEOs. Self-assessment is no cursory glance in the mirror but rather an exhaustive culling of quantitative and qualitative data through surveys, confidential interviews, and facilitated group discussions.

The investment is worth it. By making routine the practice of rigorous introspection, boards ensure that they are fit to cope with existing circumstances and adapt to new ones.

The Right Role

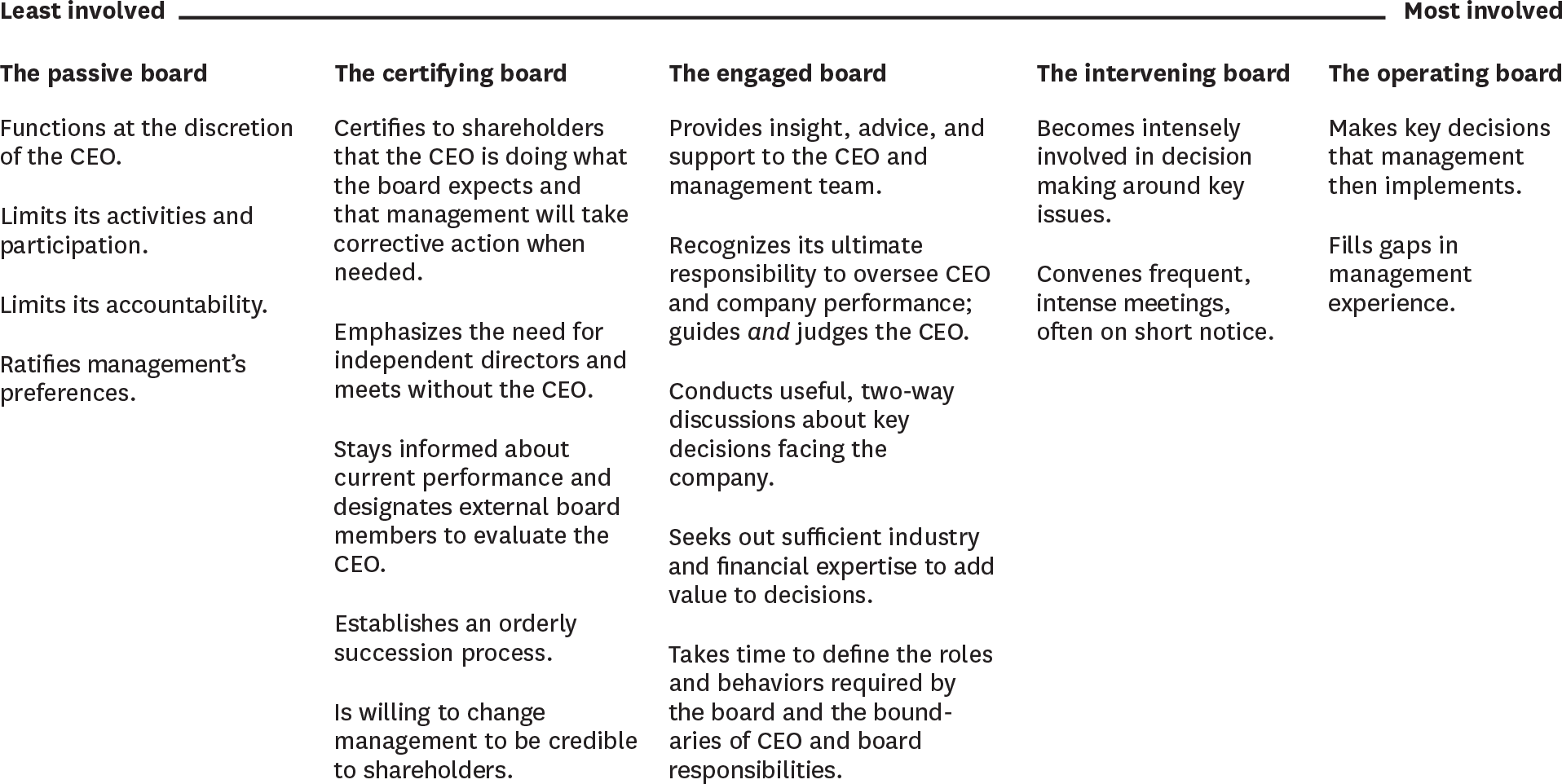

Like most quests for change, board building begins with a vision. Specifically, boards must decide how engaged they want to be in influencing management’s decisions and the company’s direction. With this step, they move beyond the letter of reform and begin to focus on its spirit. We have identified five board types that fall along a continuum from least to most involved. (See the exhibit “How engaged should we be?”) At the start of any board-building program, the directors and the CEO should agree among themselves which of the following models best fits the company.

At the start of any board-building program, the directors and the CEO need to agree what their level of involvement will be. The following are five possible board models, which fall along a continuum from least to most involved.

The passive board

This is the traditional model. The board’s activity and participation are minimal and at the CEO’s discretion. The board has limited accountability. Its main job is ratifying management’s decisions.

The certifying board

This model emphasizes credibility to shareholders and the importance of outside directors. The board certifies that the business is managed properly and that the CEO meets the board’s requirements. It also oversees an orderly succession process.

The engaged board

In this model, the board serves as the CEO’s partner. It provides insight, advice, and support on key decisions. It recognizes its responsibility for overseeing CEO and company performance. The board conducts substantive discussions of key issues and actively defines its role and boundaries.

The intervening board

This model is common in a crisis. The board becomes deeply involved in making key decisions about the company and holds frequent, intense meetings.

The operating board

This is the deepest level of ongoing board involvement. The board makes key decisions that management then implements. This model is common in early-stage start-ups whose top executives may have specialized expertise but lack broad management experience.

The point of this exercise isn’t to pack boards into rigid boxes. These characterizations are, after all, essentially archetypes. Real-world boards slide back and forth across the scale, their levels of engagement changing as issues and circumstances do. A passive or certifying board in crisis, for instance, may morph temporarily into an intervening board to remove the CEO, and then into an operating board until a new leader is in place.

Still, selecting a level of engagement provides the philosophical framework for everything that follows. Simply having that conversation is a significant first step toward improved board performance. The board may find that it disagrees sharply with the executive team about its role; or that individual directors harbor divergent views, making it difficult to act in concert. Having characterized itself to itself and to management, the board can evaluate each subsequent decision for fidelity to the model.

The Right Work

Establishing an overarching level of engagement helps board directors set expectations and ground rules for their roles relative to senior managers’ roles. But an engagement philosophy—like most expressions of general principle—does not apply equally to all spheres of activity. Boards, after all, potentially participate in dozens of distinct areas.

Many board tasks are familiar legal obligations: approving mergers and acquisitions; providing counsel to senior management; hiring, firing, and setting compensation; evaluating the CEO; ensuring effective audit procedures; monitoring investments; and so on. The latest governance requirements call upon boards to spell out those duties in written charters. At the end of each year, they go down the checklist and affirm, “Yes, we did that.” But that is a recipe for compliance, not necessarily for good governance. A better approach is to translate these mandates into categories of work, each composed of several activities.

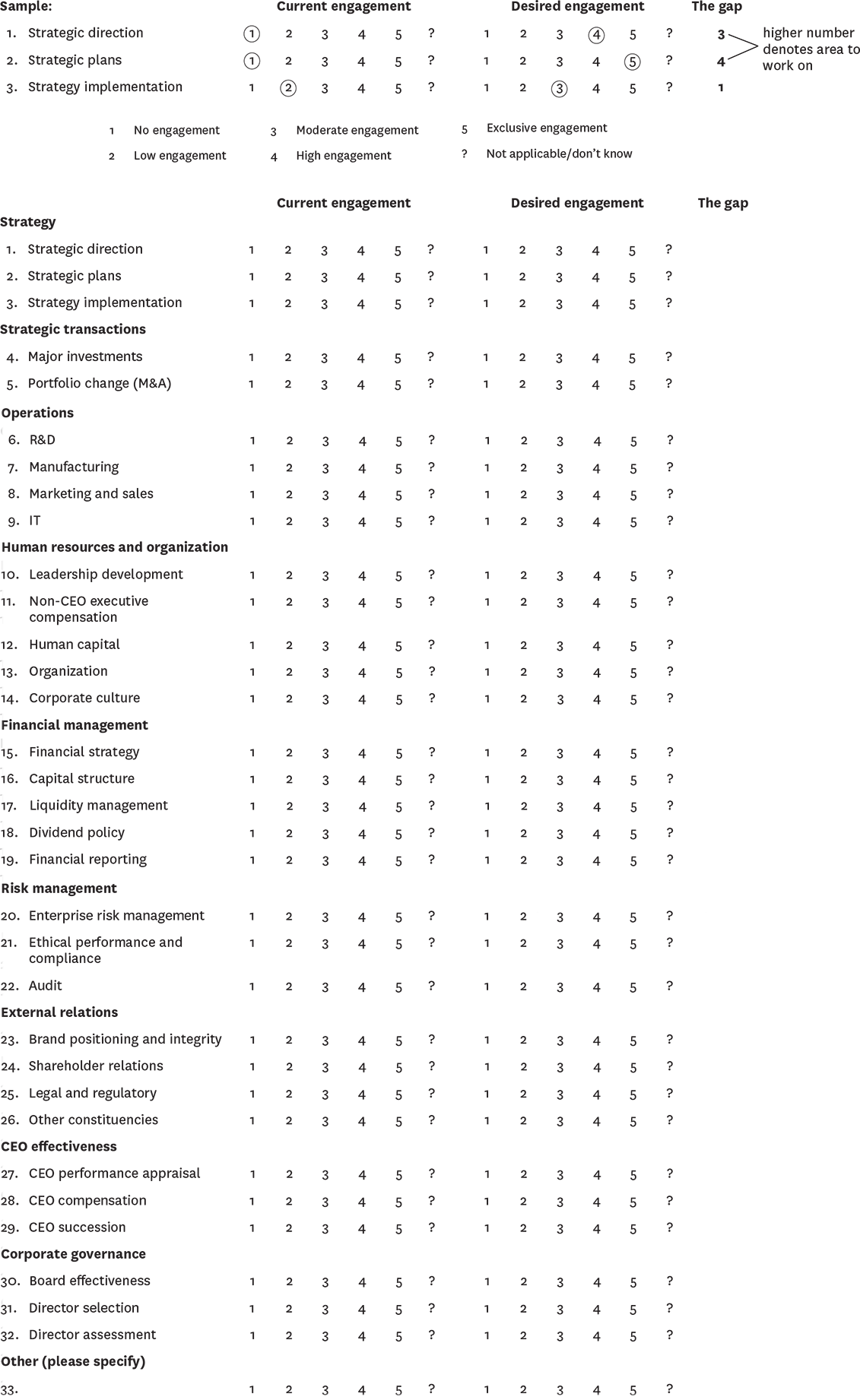

Using a form like the one shown in the exhibit “Which tasks are most important?” directors can rate the existing and optimal levels of engagement for each activity on a sliding scale. Activities that are chiefly management’s responsibility receive a one; activities that fall exclusively within the purview of the board get a five. Senior managers should fill out the same form.

Which tasks are most important?

Using a form like the one shown here, board directors and management can rate the existing and optimal levels of board engagement for each strategic business activity on a scale of one to five. (One represents areas that are chiefly management’s responsibility, and five represents areas that are exclusively the board’s responsibility.) This exercise may surface gaps between where the board needs to be focused and where it is actually spending its time and resources.

The results provide fodder for two forms of gap analysis. First, by comparing actual and desirable levels of engagement for each activity, the board can plot in great detail where to pump up or down its energies. Second, juxtaposing directors’ and managers’ views of the board’s role may surface disagreements that otherwise act like submerged mines. Occasionally, the reverse happens: The directors at one large media company we worked with, for example, were pleasantly surprised when managers rated the board’s optimal involvement in some areas higher than the board had rated itself.

This exercise has other applications as well. As the directors are considering all the scenarios that might require changes in involvement, they’re forced to contemplate the future. The board can also use this form to track how well it is fulfilling its self-defined mission and whether meetings devote the right amount of time to the right topics. Finally, it is a starting point to determine whether directors possess adequate skills, experience, and knowledge in the areas that matter most.

The Right People

A team is only as good as its members, and high-quality board members are alarmingly scarce. Eighty-one percent of our survey respondents said it’s become more difficult to recruit qualified directors; close to 40% said their boards lack an effective process for selecting new members.

In addition, reform efforts unduly emphasize several narrow aspects of board composition. Sarbanes-Oxley prescribes a heavy dose of independent directors, but the real issue isn’t independence; it’s competence. We are not referring merely to the technical expertise of audit committee members but to all competencies related to the company, its environment, and its industry.

Composition assessments look at both the collective capabilities of the board and the attributes of each director. Again, our survey is revealing. More than 90% of respondents said their boards possess the collective capabilities to be effective. By comparison, directors’ individual proficiencies inspired less confidence. Only:

73% of respondents said their colleagues have detailed knowledge of the company’s industry;

69% said their colleagues have accounting and public-reporting expertise;

61% said their colleagues understand the company’s key technologies and business practices;

60% said their colleagues possess expertise in global business issues;

58% said their colleagues contribute potentially valuable external contacts.

The work-categories exercise described earlier is the cornerstone of composition assessment. Boards take inventory of each director’s strengths—based on professional experience and technical knowledge—and align them with activities that require maximum board involvement. The resulting capabilities profile illustrates the match—sometimes the alarming mismatch—between what the board needs and what directors can actually do. Such knowledge is critical for producing director recruitment profiles.

Continental Airlines, for example, was determined to enlist the best directors possible to help fight the battles engulfing its industry. The board thoroughly analyzed the company’s business issues to determine what skills and experience it needed. Directors zeroed in on knowledge of the airline and travel industries, an understanding of marketing and consumer behavior, access to key business and political contacts, and experience with industry reconfiguration.

The board then defined the capabilities and qualities expected of all directors, such as independence, business credibility, financial expertise, confidence, and teamwork. To be as representative as possible, it took into account directors’ knowledge of geographic markets—particularly their knowledge of key Continental hubs—CEO experience, leadership in the business sectors, and gender and ethnic diversity.

Next, the board assessed all of its directors and mapped their skills, experience, and backgrounds against the new criteria. The gaps became fodder for hypertargeted recruitment profiles. In the end, several board members voluntarily stepped down to make way for new directors who had the capabilities Continental needed to compete successfully.

Capabilities profiles also provide a safe mechanism for directors and senior managers to broach sensitive subjects. “For about a year, I’d wanted to raise the issue of recruiting more directors with industry experience,” said the CEO of a Fortune 500 company involved in a massive turnaround. “I felt sure this issue would make several board members defensive, so I held off.” Then the board performed a composition assessment. “To my surprise, they raised this issue themselves,” the CEO told us, “and tasked the nominating committee to develop a list of board candidates with exactly the kind of experience I felt we needed—all without my having to be the heavy.”

Evaluating personal performance, of course, requires precision and delicacy. It is not surprising that 76% of our survey respondents report that the boards on which they sit conduct no individual assessments. Under growing pressure to perform, however, boards must recognize which directors need help, which should not be nominated for another term, and which should be cut loose. Consequently, more boards are adopting formal assessments of individual directors, including peer review.

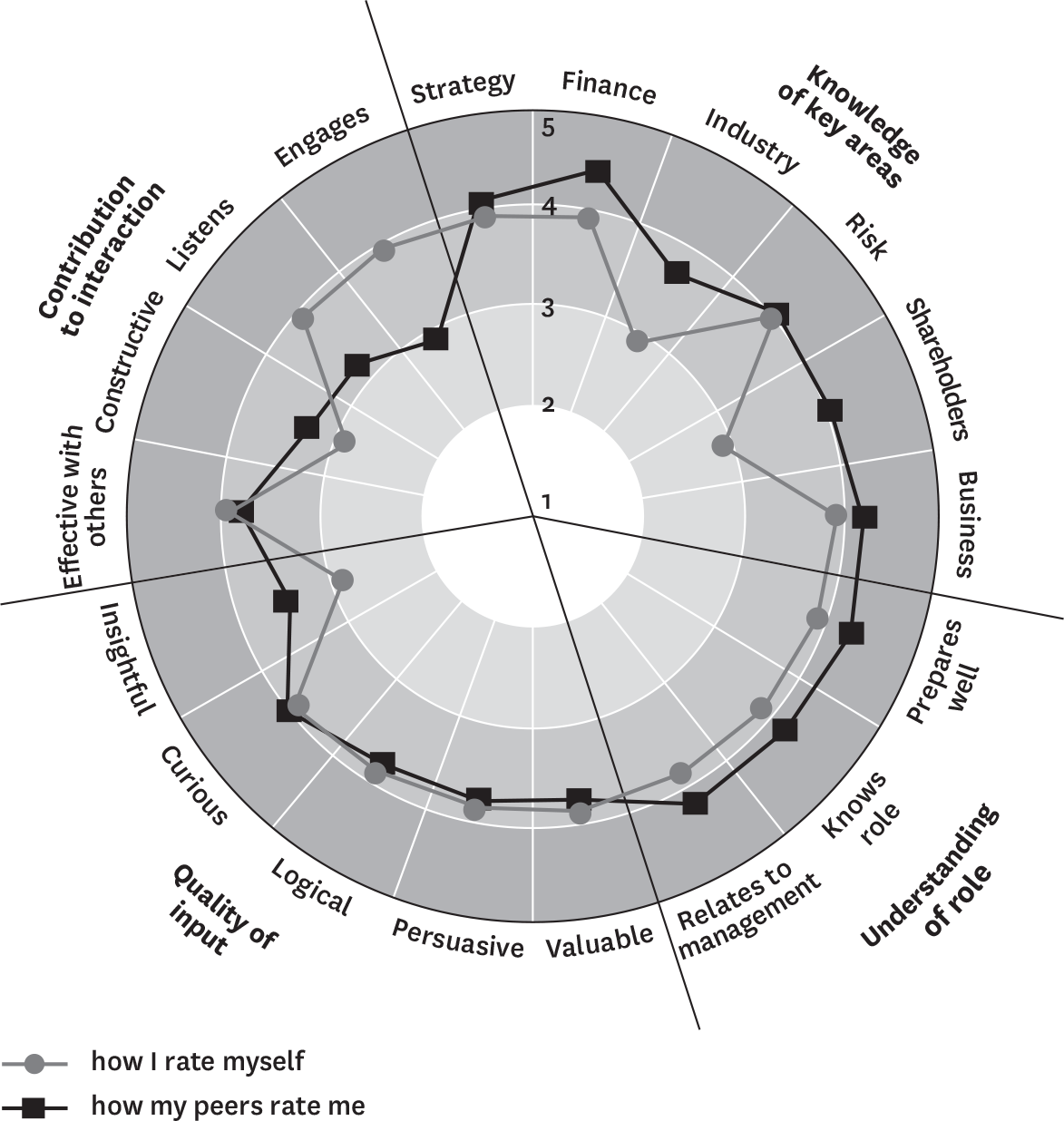

The peer review at one multinational financial services company illustrates how such assessments work. It comprises 18 questions rating individual members’ demonstrated knowledge of key areas, their understanding of and preparation for their roles as directors, the quality of their input or advice, and their contributions to board interaction. All board members, including the member being evaluated, fill out the form. (The exhibit “What are our members’ strengths and weaknesses?” compares the ratings one director gave himself with the ratings others gave him.) The company furnishes such reports to each board member and to the board’s independent chairman, who uses them to guide discussion during directors’ annual reviews. Peer feedback has influenced decisions about recruitment, retirement, committee leadership and selection, and education initiatives for directors.

What are our members’ strengths and weaknesses?

Use of peer-review tools is becoming more common among boards interested in formally assessing their individual directors. In the example here, the performance of one director at a multinational financial services company was rated on a scale of one (lowest performance) to five (highest performance) in four areas: contributions to board interaction; knowledge of key areas; understanding of director’s role; and quality of input at meetings. His peers generally gave him more credit for his knowledge than the director gave himself. But when the subject was interaction, the director's peers perceived him as undermining board deliberations by talking too much, listening too little, and squelching constructive debate. Meanwhile, the director clearly considered listening and engaging to be among his strong suits.

The Right Agenda

Agenda management is a mundane-sounding subject if ever there was one. Agendas, however, dictate what the board discusses and at what length. To control the agenda is to control the work of the board.

Historically, management has been in control. Nearly 60% of our survey respondents said they can’t influence their own agendas. The result has been decades of choreographed ceremonies substituting for meetings where real work gets done. At many companies, directors routinely endure a parade of precisely scripted presentations, occasionally followed by perfunctory discussion and the inevitable vote to ratify management’s recommendations. CEOs, if so inclined, can overload the agenda with so many show-and-tell segments that they crowd out serious questions, troublesome concerns, or authentic debate.

“At many U.S. companies, the board meetings are shorter, and there’s much less discussion,” says one retired CEO who has sat on the boards of both U.S. and European companies. “It’s more, ‘Bang, bang, here’s a nice presentation on interesting issues.’ It’s like going to a diner for a meal. If you don’t finish your food fast, they will take it away from you.”

But with the call to accountability, corporate boards can no longer doze behind the wheel while management steers. To the extent that CEOs participate in the board-building process (and CEOs must participate in the board-building process) they acquiesce to some level of power sharing—a high level in the engaged, intervening, and operating models. The presiding director can collaborate with the CEO to devise an agenda agreeable to both. Alternatively, at the end of each board meeting, participants can collectively set the agenda for the next one. In any case, the rating of tasks (which, you’ll recall, has been blessed by both the board and management) is the touchstone. Directors and managers can review the agendas and minutes of meetings past to ascertain how much time they devote to each area. They then compare those findings with the board’s priorities to establish a correlation between interest bestowed and time spent.

The board at Target, a corporate governance leader, has gone further, transforming agenda management into something of an art. At the start of each year, the board sets three top priorities—for example, strategic direction, capital allocation, and succession planning. It then places each topic at the top of the agenda for at least one upcoming meeting. Target’s board also devotes one meeting a year to setting the strategic direction for each major operating division, an acknowledgement of the company’s growing complexity. Directors never stint on questions and debate, requiring management to submit major items for board approval at least one meeting prior to the scheduled vote so they have the chance to discuss them. But they are chary of their time and insist that presentations be short and to the point.

Boards should find ways to stay engaged with the company’s issues outside of regular meetings as well. Even without managerial diversions, board meetings are simply too packed with must-accomplish items to allow an in-depth examination of any one. That is frustrating for directors who want to dig deeper into the meatiest subjects, most notably succession planning and strategy. Annual off-site meetings or retreats, one-on-one conclaves involving CEOs and directors, and sit-downs between groups of directors and employees who have common interests all make the intervals between meetings fruitful.

The board’s standing committees can also provide continuity. In response to the heightened focus on accounting and financial reporting, for example, many audit committees now meet—in person or via teleconferencing—more often than the board as a whole. Certainly, committees give directors the chance to concentrate on specific issues, developing deeper expertise in the process. But in general, boards have come to rely less and less on committees, motivated in part by the concern that some will emerge with greater influence than others and impair directors’ ability to work together.

The Right Information

The corporate secretary of a major company explained to us the “dark side” of communications between senior management and the board. “There are two equally effective ways of keeping a board in the dark,” he said. “One is to provide them with too little information. The other, ironically, is to provide too much.” The secretary went on to describe his own experience on the board of a public corporation: “We received reams of financial information in advance of each board meeting, which was way too much to absorb and could not be properly understood without considerable background information.”

Thus do boards fall prey to the confusion of data with information, which is no less real a problem for being a cliché. Too many board directors are overwhelmed by fat stacks of often insignificant numbers but lack the right information presented in the right way to produce informed action. We’re constantly surprised—though perhaps we shouldn’t be—when directors who have served on boards for years confess that they don’t really understand how their companies make money.

Certainly, boards face a huge information challenge. Directors are outsiders with limited time to learn about the company. If knowledge is power, then the balance lies with managers, who live and breathe operations. Indeed, only 28% of the directors in our survey said they have independent channels for obtaining useful information about the company. The rest rely on what management chooses to share with them. Throughout our research, directors asked us repeatedly, “How can I tell what’s really going on?”

In some cases, a little class time helps correct the imbalance. One company we worked with, for example, decided that its board lacked the background to intelligently review its strategy, business model, and performance. So the CFO walked audit committee members through the company’s balance sheet line by line and later did the same for the entire board in an intensive three-hour workshop. Directors, including some who had been on the board for years, came away with a much better understanding of important issues.

In that case, the board diagnosed its own problem. Other boards, however, suffer from a more general discomfort: the feeling that something is missing or preventing them from doing their jobs. Often, that something is a particular kind of information. The board of Axcan Pharma, for example, conducted a self-assessment that exposed concern about the conflation of chairman and CEO roles. Further conversations narrowed the focus: Directors, it turned out, worried less about the conflation of roles than about a lack of information regarding acquisitions the CEO was pursuing. The solution was to change the information flow to the board rather than separate the two roles. Similarly, at Best Western, directors expressed dissatisfaction about the board’s role in strategic direction. Their chief complaint? They weren’t getting information on risks and returns before being asked to ratify major initiatives.

Such knowledge malnutrition is common. Boards often subsist on just two sources of information. The first is retrospective data on corporate performance and operations—in other words, trailing indicators. The second is presentations by management—particularly by the CEO, whose articulation of a vision and interpretation of financials significantly shape boards’ views. Given those meager rations, it’s no wonder companies get into deep trouble before their boards find out.

Not long ago, we worked with a board that was under sharp criticism for taking too long to remove a CEO following major performance shortfalls and spectacular valuation declines. But the directors shouldn’t have been faulted for dragging their feet. As one explained, “Six months ago, we had a very articulate CEO who made a very eloquent case about the company, and we had financial measures that indicated we were one of the most valuable market capitalization companies in the country. How were we to know what was going on below? In fact, once we saw the problems, we acted with blinding speed, although in many ways it was too late.”

It is management’s responsibility to ensure that boards get the right information at the right time and in the right format to perform their duties. The best boards design processes to deliver formal information that combines both leading and lagging performance indicators, which will vary by industry and company. But boards should also be free to collect information on their own, informally and without management supervision. Directors at General Electric and Target, for example, are required to periodically visit company facilities unaccompanied by senior executives.

The Right Culture

Against a backdrop of governance progress, many boards appear positively antediluvian. The boardroom is dark and richly paneled. A plaque engraved with a member’s name adorns each chair. No one argues passionately about anything. Robert’s Rules of Order prevail.

Those are just some visible artifacts of traditional board culture—a huge obstacle to directors seeking greater engagement. Culture is a system of informal, unwritten, yet powerful norms derived from shared values that influence behavior. We know that culture affects teams: Even those doing the same work with identical structures and similar composition perform differently depending on their social systems and beliefs. Thus, passive boards, governed as they are by formality and reserve, will perform differently from boards like the one described in the sidebar “Do We Have an Engaged Culture?” Engaged cultures are characterized by candor and a willingness to challenge, and they reflect the social and work dynamics of a high-performance team.

Structures, composition, information flow—these things can be designed. Culture, by contrast, develops over time and tends to reward those who perpetuate it, making it difficult to change. At one financial institution in the midst of a self-assessment, some directors argued for a more open and participatory culture. But the majority clung to the status quo. Proponents of change recognized that as long as the board’s composition stayed the same, the old culture wasn’t going anywhere.

Boards cannot easily change their cultures. But as members start to act as a team, board cultures will change. The closer directors get to an engaged culture, the closer they are to being the best boards possible.

Although governance reform is, strictly speaking, an imposition, boards should view it as a catalyst. Yes, it is far harder to clean house than to simply tidy up, but the rewards are proportionately greater. An ambitious board-building process, devised and endorsed by directors and management, can turn a good board into a great one. But that transformation happens only when boards define their optimal roles and tasks and marshal the people, agendas, information, and culture to support them.

At its most effective, board building contributes not only to performance but also to member satisfaction. “I’ve served on this board for nearly ten years, and this is the first time I’ve really sat down and thought about how we have been working together,” said the director of a consumer products company engaged in such a project. “Our discussions always focus on how we are addressing everything on the overloaded agenda. Now that I’ve spent some time thinking about this, there are definitely some things we could do better.

“It also made me think about why I joined this board in the first place,” he said. “Somewhere between all the meetings and the calls, I seem to have lost sight of that.”

Originally published in May 2004. Reprint R0405G