Dysfunction in the Boardroom

by Boris Groysberg and Deborah Bell

FOR YEARS women have sought greater representation on corporate boards. And most boards say they want more diversity. So why did women hold only 16.6% of Fortune 500 board seats in 2012? And why, for the past six years, has that percentage been relatively flat, increasing by just two points, according to data from the research firm Catalyst?

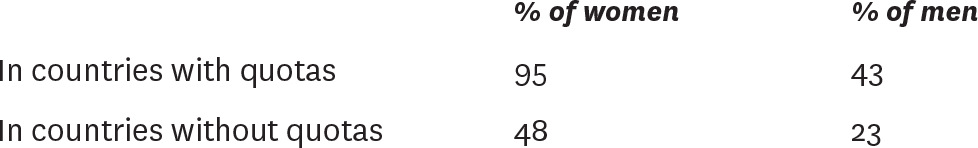

Patience has started to wear thin, especially in Europe. Having seen little progress with voluntary efforts, several countries, including Belgium, France, Iceland, Italy, Norway, Spain, and the Netherlands, have enacted legislation that calls for a minimum percentage of female directors on boards. The European Union is considering mandating quotas as well.

It’s unclear why women have not made greater inroads. Board appointments and dynamics remain largely a black box; not much research has been done on the selection and appointment process or on the differences between women’s and men’s experiences as directors. To learn more, in 2010 we began a series of annual surveys in partnership with WomenCorporateDirectors and Heidrick & Struggles. In this article we reveal the findings of an analysis of qualitative data from the first survey.

We were especially interested in the backgrounds, trajectories, and interactions of female directors—who are the women who get onto boards, and what do they encounter there? So our sample was drawn mainly from female corporate directors; we included a smaller number of male directors as a benchmark. (Overall the survey had a response rate of 42%, with 294 women and 104 men from private and public companies participating.) Also, because the vast majority of the sample consisted of U.S. directors (80% of the women and 83% of the men), the findings largely present a picture of American boards. While our survey has these and other limitations, it still offers several interesting perspectives.

In the following pages, we’ll share a profile of the female board member that emerged; what the directors surveyed had to say about the benefits of diversity and about the dynamics between men and women on boards; and some best practices for recruiting and managing diverse boards. In the process, we’ll discuss three key themes we discovered in the data:

Women had to be more qualified than men to be considered for directorships. Women also seemed to pay a higher personal price to become board members than men did.

Although boards say they like diversity, they don’t know how to take advantage of it. We found a stark disconnect between female directors’ experiences and their male colleagues’ perceptions. Women told us they were not treated as full members of the group, though the male directors were largely oblivious to their female colleagues’ experience in this regard.

Great talent alone is not enough to create a well-functioning board. Boards need formal processes and cultures that leverage each individual member’s contribution as well as the directors’ collective intellect.

Portrait of the Female Director

In our study, we observed some distinct patterns. The female directors tended to be younger than the male directors—probably because, on average, the women had joined boards relatively recently, whereas the men had served on boards longer. Seventy-six percent of the female directors (versus 69% of the male directors) were employed in an operational role; 68% (versus 51% of the male directors) were in a lead role, like CEO, president, or partner. These findings suggest that to receive invitations to boards, women might need to be more accomplished than men. They also contradict the popular belief that female board members have mostly nonoperational or support-function experience.

Another distinction we discovered between the backgrounds of female and male directors was that by and large, the women on boards worked for private corporations, not public ones. A majority of the male board members worked for private corporations as well, but a higher percentage of the men worked for public companies—likely a reflection of the fact that fewer women occupy the C-suites of public companies.

The data also indicate that female board members may have made different trade-offs on their way to the top. In comparison with male directors, fewer female directors were married and had children. A larger percentage of the women were divorced—suggesting they may have incurred greater personal costs. We found similar patterns in our 2012 survey.

We were curious to learn about the aspirations of corporate directors, who by most standards have reached the pinnacle of career success. We found that a somewhat higher proportion of women than men (92% and 86%, respectively) described themselves as ambitious. In addition, contrary to gender stereotypes, 91% of the women versus 70% of the men reported that they enjoyed having power and influence.

On average, the women in our survey were serving on two boards and the men on three. Given that, it wasn’t surprising that over half the female directors wanted to serve on more boards. (A smaller percentage of the men did.) But the women also expressed greater overall career aspirations. Twenty-seven percent of the female directors wanted to lead or continue leading a company, compared with 19% of the men. Although female directors’ younger age may account for some of the difference, it doesn’t fully explain it: Twenty-nine percent of the women who actively aspired to the top job were age 60 to 70, whereas only 10% of the men with similar aspirations were. Such ambition at a time of life when most professionals are winding down their careers suggests that women, whose opportunities have consistently been more restricted, may wish to extend the length of their careers with an eye to finally attaining the most-coveted roles.

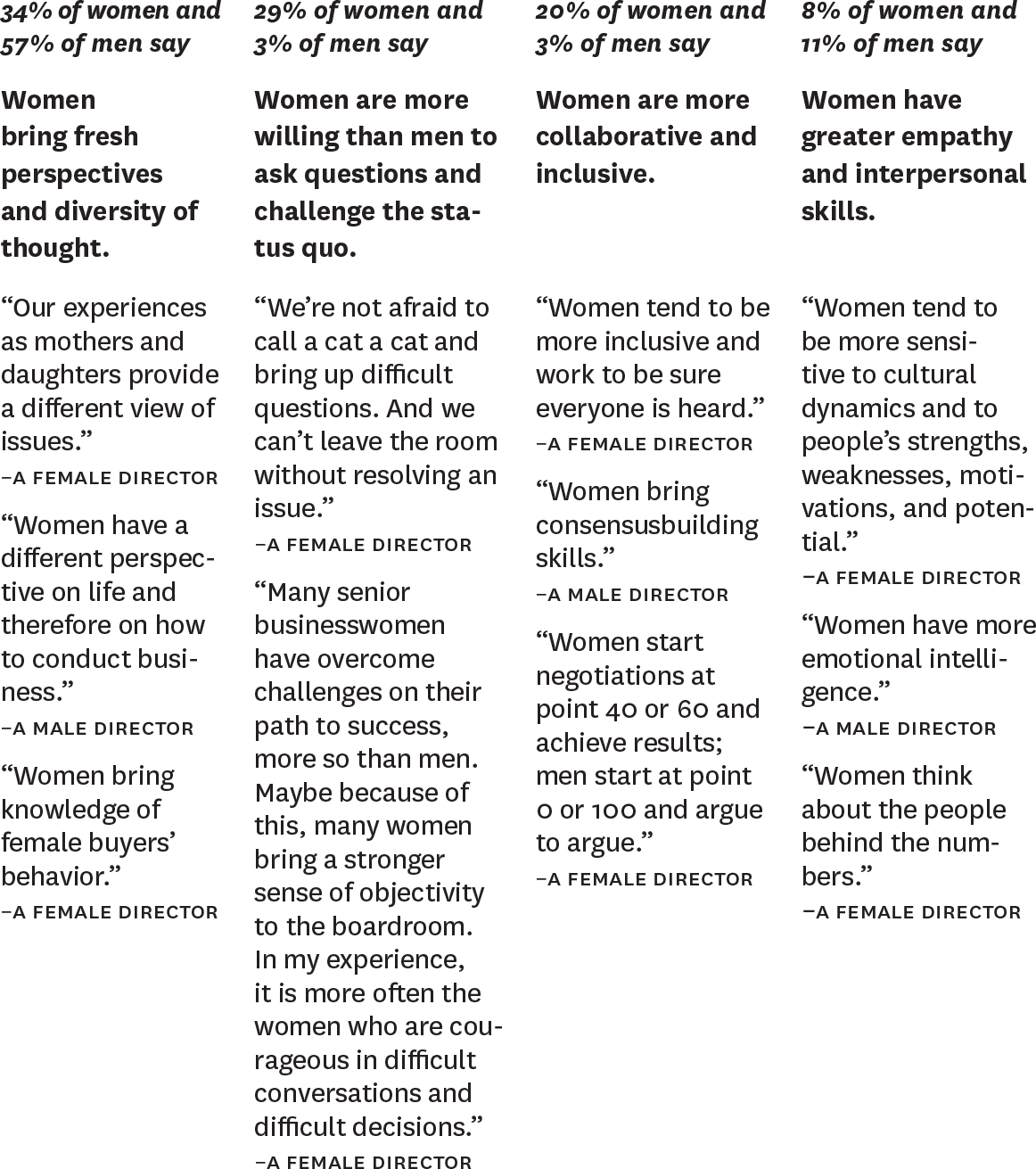

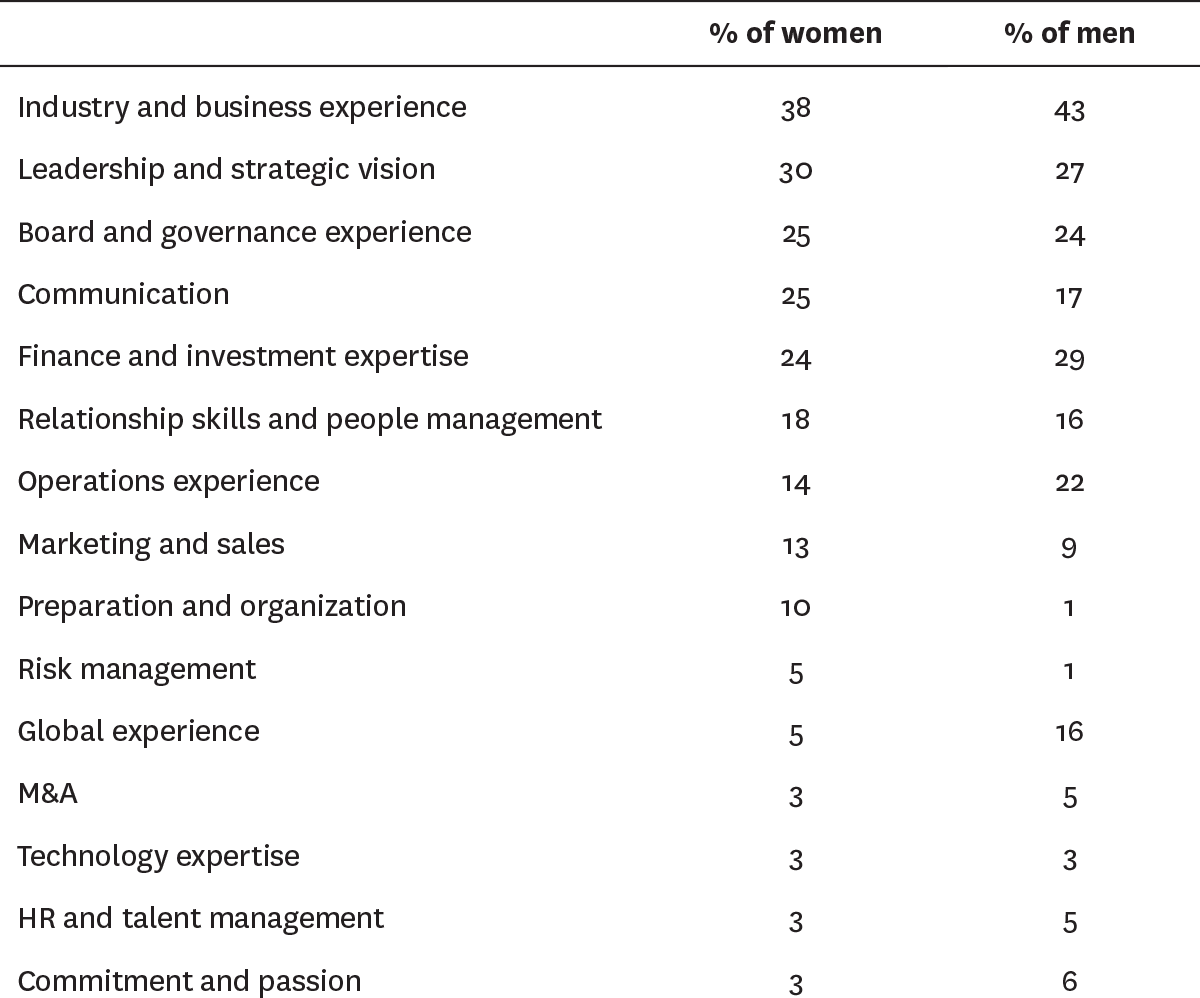

We also wanted to know what strengths directors would say they brought to their boards and, by implication, what skill sets and areas of expertise they thought were most important to board operations and dynamics. Asked to write in their strengths, the men and women gave remarkably similar answers. One significant difference was that a lot more women than men cited the ability to communicate effectively. Many female directors noted that they were more likely than their male counterparts to ask tough questions or move boardroom discussions forward in skilled and effective ways. (See the chart “How female and male directors perceive their strengths.”)

How female and male directors perceive their strengths

We asked survey respondents to write in what their strengths as board members were. Here are the traits and skills they noted.

Another notable difference was the greater percentage of men who cited global experience as a strength. In our work with directors and high-level executives, we’ve found that women are often not considered for international assignments, because of the assumption that women with families find it more difficult than men with families to relocate or travel for extended periods. The unfortunate consequence is that women don’t get equal access to international roles.

Curiously, more men than women listed operations experience as a strength, even though a greater percentage of the women held operational roles or were leading a company. We cannot say why with certainty, but their answers indicate that women may place a higher value on personal skills, such as leadership and communication, than on role-related experience.

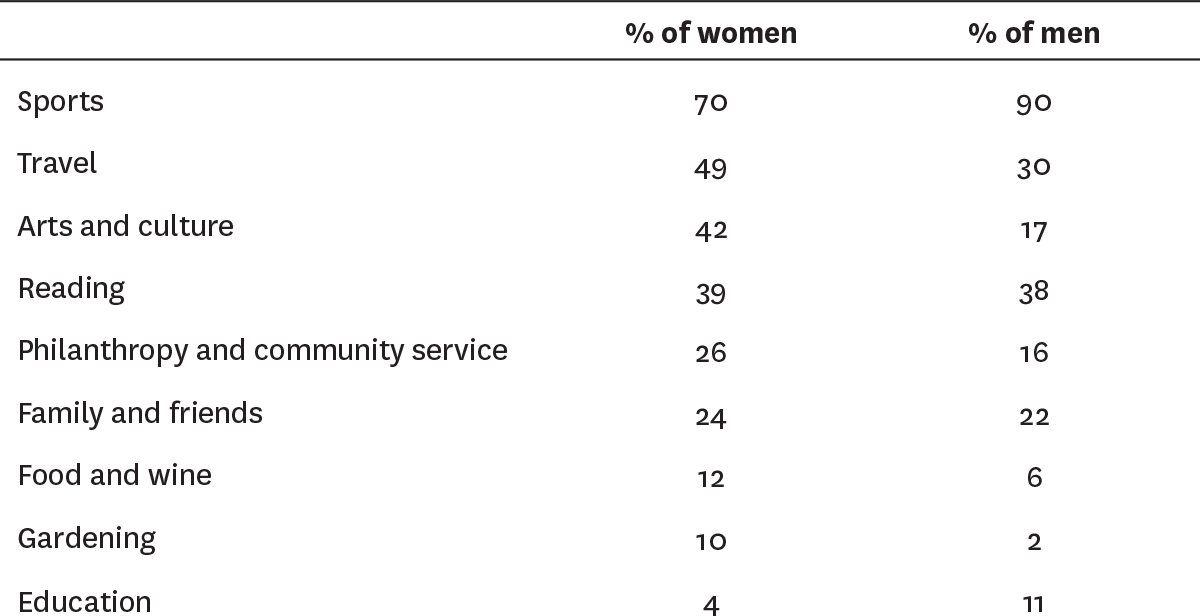

To learn more about the factors that may inform directors’ perspectives, we asked about their outside interests. We found substantial differences between women and men. Though both named sports most frequently, men did so at a much higher rate. (See the sidebar “Golf, Anyone?”) What was also striking was the higher percentage of women than men who named arts and culture, travel, and philanthropy and community service as outside interests. (See the chart “Directors’ outside interests.”)

To learn what shaped board members’ perspectives, we asked directors about their nonwork interests and activities.

How might these differences affect the way female and male directors form and maintain connections with other directors? Could the lack of common interests make it harder for female and male board members to identify with and relate to one another? Or could these differences be enriching?

The Benefits of Diversity

According to research by our HBS colleagues Robin Ely and David Thomas, organizations have three major approaches to diversity. We’ve found that boards’ approaches to diversity are similar. They may pursue it as a way to:

Institute fairness and rebuke discrimination. Government interventions, whether mandatory (quotas) or voluntary (targets or disclosure reporting recommended by the SEC), have sensitized most boards to the fairness argument for diversity.

Build a deeper understanding of and access to desirable customer bases and markets, such as female consumers.

Incorporate new perspectives and generate learning. When this is the goal of a board, diversity is integrated into all its practices and informs all discussions and decisions, producing the greatest impact.

To better understand what directors think gender diversity can offer boards, we asked respondents whether women bring special attributes to the role. Ninety percent of the female directors thought they did, compared with 56% of the male directors. Below are the attributes respondents cited, along with representative comments.

While slightly more than half of the male directors said that women bring a fresh perspective to the boardroom, 19% said that gender should not be a factor when selecting directors; instead, selection should be based solely on qualifications and experience. One male director explained, “Women—and any board member—should be judged on their background and skills, not because they have attributes based on gender, race, etc.” Another stated, “People bring special attributes, and they are not related to diversity.” And a third offered this view: “Any shareholder wants the most qualified board members they can get. Diversity is a plus.”

Many people have no doubt that women account for more than 16.6% of the pool of highly qualified potential directors, so the question remains: Why aren’t more women on boards? One female director offered this explanation: “Women are not thought of first as candidates unless a board is looking for gender diversity specifically.” Another shared her experience: “I’m not part of the old boys’ network. Directorships go to people who are known. I’ve been so busy leading my company and raising my family that I’m less well known.” And a third lamented, “Boards still prefer pale, stale, and male!”

Gender and Board Dynamics

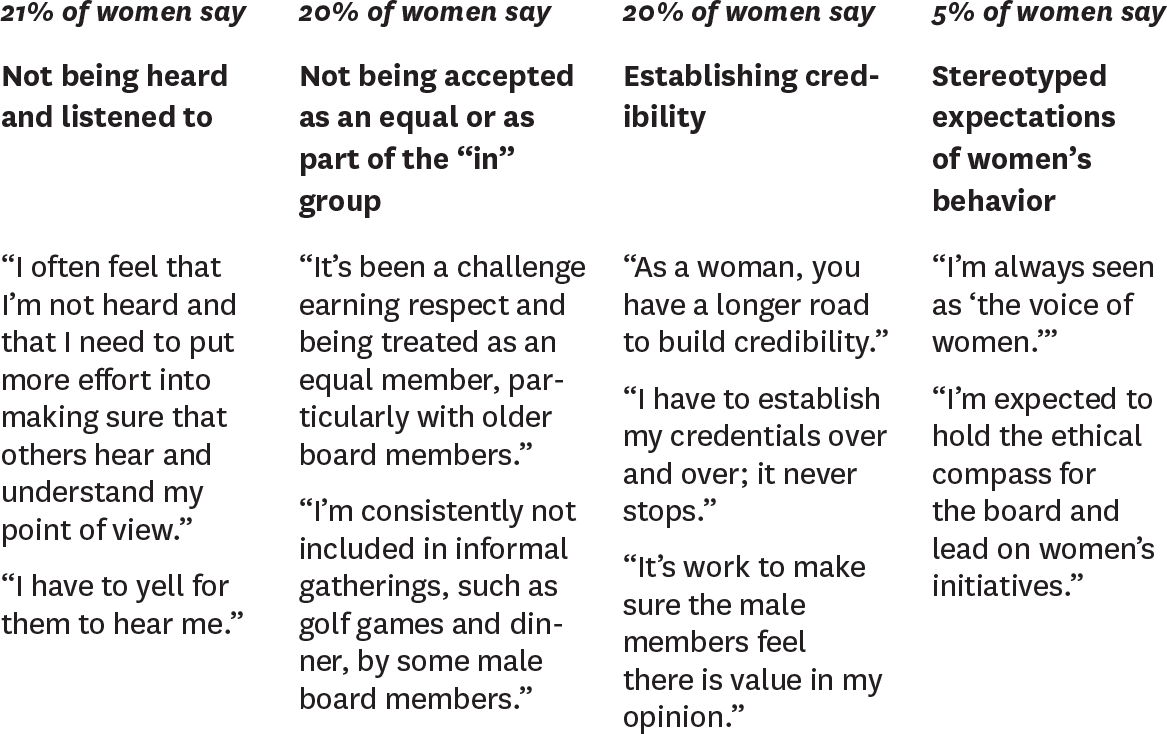

Though boards say they want diversity, what happens once women get on them? Eighty-seven percent of female directors reported facing gender-related hurdles. The obstacles fell into four major categories, listed here along with examples of the types of comments we heard most.

We also asked the male directors if female directors face hurdles that men do not. The majority—56%—said no. Those who answered yes named the four types of barriers listed on next page (with a sampling of their comments).

According to some women’s accounts, many male directors seem unaware that they may create hostile board cultures, fail to listen to female directors or accept them as equals, and require them to continually reestablish their credentials.

One female board member gave the following example: A highly successful and accomplished woman in financial services was asked to join the board of a growing multibillion-dollar public company. She was its first and, for many years, only woman director. She brought greatly needed financial expertise to the board as well as a deep understanding of the company’s industry, yet she routinely felt shut out and stifled during meetings. Her questions were greeted not with respectful collegiality but as intrusions into the “real” conversation among the male board members.

In fact, the CEO and chairman and other male directors had taken her aside many times and asked her to be “less vocal” and to “stop arguing her point” during meetings. She related how this behavior surfaced during meetings, too, recalling one in particular at which she was pursuing a line of questions about a strategic decision when a male director interrupted her and exclaimed, “You’re behaving just like my daughter! You’re arguing too much—just stop!”

This story illustrates the kind of experience that may have led female directors to cite the failure of their board colleagues to listen to them more often than any other barrier. The fact that few men recognized this dynamic suggests a stark disconnect between female directors’ experiences and their male colleagues’ perceptions.

In addition, far more male than female directors (28% versus 4%) pointed to a lack of board experience and industry knowledge as a handicap for women, but our findings indicate that men and women may come at the qualifications question from very different perspectives. Men seemed to view inexperience as a fixed and disqualifying trait, whereas women saw it as surmountable-something that could be addressed through learning and development. The high percentage of female directors who held operational roles and were leading organizations implies another disconnect—this one between women’s qualifications and men’s perceptions.

Diversity in Practice

In their responses to our survey, both male and female directors repeatedly named open communication, well-run general meetings, a candid but collegial tenor, and productive relationships with senior management as attributes of a successful board. Yet research suggests that too many boards ignore the need for those qualities, and recent efforts to overhaul governance have clearly failed to address the question of how to compose a knowledgeable, inclusive body that possesses them.

We studied a large company that was being split into two public companies for which two new boards had to be created. The chairman, who had long championed diversity, was spearheading the process. He appointed a special team to create an objective, transparent method for selecting the directors. After reviewing the roles and responsibilities of each board and the natures of the new businesses, the team derived lists of the skill sets each board needed. Then it created a model containing the dimensions critical to a high-performing board, from functional and industry expertise to behavioral attributes. This approach led both companies to recruit boards that were diverse not only in gender but also in skills—demonstrating that when a firm builds a board using a rigorous assessment of the qualities it needs to carry out its governance task, rather than personal networks, the board is better equipped to execute its functions.

Though more research is needed to measure the impact of different practices on board performance, we have encountered several (detailed on the next page) that boards have used to become more effective. Practices like these help break down obstacles that hinder directors from being fully integrated into boards and contributing to their potential.

After all, as our data suggest, it takes more than great talent to make a great board. Talent alone cannot overcome dysfunctional dynamics. Companies increasingly recognize the distinction between diversity and inclusiveness: Diversity is counting the numbers; inclusiveness is making the numbers count. Boards need to improve on both dimensions.

Originally published in June 2013. Reprint R1306F