Emma Lazarus’s huddled masses, Thomas Bailey Aldrich’s wild motley throng, and Prescott Hall’s beggar, thief, and scum generally entered the United States in the same fashion: from deep within the bellies of the transatlantic ships that steamed into American harbors. Steerage travel was perfected by Albert Ballin, a lower-middle-class Jew from Hamburg who eventually rose to become the chief executive of the mammoth Hamburg-American Line. At one point Ballin had 175 ships at his command—a fleet larger than the merchant marine of any European power except Germany itself. Hamburg-American vessels had been coming to America to ferry timber and other products eastward to Europe. Contemplating the empty, wasted space on the westbound leg, Ballin conjured a commodity that could fill it, a commodity far more valuable than timber: immigrants. As it happened, filling a vessel’s hold with hundreds of passengers had a subsidiary benefit: the added ballast made the ship easier to steer.

Ballin’s vision became phenomenally lucrative for his company and all the other shipowners in Hamburg and Bremen and Rotterdam, in Liverpool and Antwerp and Naples, virtually wherever there was a European port accessible to people wishing to travel across the Atlantic. One reliable estimate, calculated in 1901, found that the cost of bringing a passenger to an American port in the cramped, dark, and unsanitary steerage compartment of an oceangoing ship cost the steamship line $1.70 (2019 equivalent: roughly $55), at a time when the average fare was $22.50 (slightly more than $700). At an allotted one hundred cubic feet per person (equivalent to a space measuring five feet by four feet by five feet), operators of the larger ships could cram two thousand immigrants into steerage, feed them a rudimentary diet of bread and herring for the ten-to-twelve-day crossing, and pull in profits previously unimagined.

To feed this bountiful money machine, steamship companies maintained networks of recruiting agents throughout the poorest parts of Europe. Priests, rabbis, schoolteachers, postmasters—anyone with a wide range of acquaintances who was also literate enough to fill out the requisite forms—could collect the equivalent of a couple of dollars’ worth of commission per traveler, payable in advance as a deposit against the price of a ticket. Francis Walker of MIT claimed that a rural notary in Hungary could earn an entire month’s income by persuading a family of five to make the transatlantic voyage. In southern Italy, the steamship companies employed more than 150 dedicated agents, who collectively ran a network of some four thousand subagents scattered through the city slums and across the impoverished countryside. One Italian-American scholar liked to tell the story of the mayor of a provincial Italian town greeting a visiting dignitary: “I welcome you in the name of five thousand inhabitants of this town, three thousand of whom are in America—and the other two thousand preparing to go.”

In eastern Europe, agents would also arrange their customers’ overland travel to the embarkation ports on the North Sea. Across the decades, tens of thousands of them passed through a bustling Polish rail junction that would prove similarly convenient for another purpose half a century later: Oświeçim, also known as Auschwitz.

The power of the steamship companies was one of three impediments that Henry Cabot Lodge had to contend with throughout his long career battling the immigrants and their advocates. Naifs like Prescott Hall of the IRL may have proceeded from the assumption that the facts were so plain, the dangers so evident, that reasonable men could not possibly disagree with him. But Lodge knew better. In addition to the steamship companies, formidable political opposition came from the massed influence of the large American manufacturing and natural resources companies avid for cheap labor, and from a third foe that Lodge was unwilling to define publicly. Weeks before Grover Cleveland stamped his veto on the literacy test, Lodge had told associates to expect it, hinting darkly that certain unnameable and “insidious” elements were likely to turn the president against them.

Lodge and his allies handled the manufacturers with relative ease, even insouciance. Samuel Gompers of the American Federation of Labor considered unrestricted immigration “this pressing evil” and formed an unholy alliance with Lodge—blue collar joins Brahmin—in support of the literacy test. (The test, Gompers would write in his memoirs more than a quarter century later, was “the only issue upon which I have ever found myself in accord with Senator Lodge.”) By adding the support of labor to the measure’s purely xenophobic appeal, Lodge had been able to outmaneuver the corporations. “We knew their strength and had beaten them,” he told an IRL official after his bill had made it through the House and Senate.

Lodge had been much more concerned about the steamship lobby, whose financial incentives for defeating the test were enormous. “I do not know when I have been [made] more indignant than by this active interference accompanied by threats to members of Congress on the part of foreign corporations,” Lodge fumed. Price wars between German and British shipowners had cut into their profits somewhat, but when Albert Ballin of the Hamburg-American Line decided to make common cause with his competitors, a lavishly funded army of opponents rallied to the antirestriction cause. Lobbyists swarmed the Capitol Building. Some members of Congress lined up for postretirement employment with the steamship companies while others, still in office, solicited direct payments. The North German Lloyd line alone enlisted more than two hundred affiliated representatives in the western states to wire their congressmen—at NGL expense—and persuade them of the abundant economic benefits that derived from open immigration. They might have turned a few minds in Congress when they suggested an alternative even scarier than an influx of illiterate Europeans. Chicago-based George W. Claussenius, who organized the effort on behalf of North German Lloyd, told reporters that the Lodge bill “discriminates against white Europeans” in favor of “negroes and half-breeds, who, while they may have our sincere sympathy, are of no use in improving western farms.”

Lodge had taken that argument and simply chosen a different line of demarcation—not the one that separated Europeans from African Americans but the one that sliced Europe in half, the northern and western countries on the protected side, the southern and eastern lands debarred. It was precisely this divide that provoked the third and most potent of Lodge’s opponents, the bloc that Lodge had labeled “insidious” and was so reluctant to discuss, at least in writing. “Influences [on Cleveland] were used yesterday which I will explain to you when we meet and which were very hard to overcome,” he told his protégé Curtis Guild Jr., a future governor of Massachusetts. To Robert Ward, the Harvard climatologist who was one of the Immigration Restriction League’s three founders, Lodge said these other forces represented neither corporations nor political factions. As he did with Guild, he declined to identify them until he could tell Ward about them in person.

Lodge seemed to derive his greatest gratification from the plenitude and power of his enemies; one contemporary said he “considers himself so far superior to the ordinary run of people that the mere addition of another enemy to his long string means nothing to him one way or the other.” But in this instance, constraining himself from describing his enemies even in private correspondence, his circumspection was more than uncharacteristic. It suggested that these enemies were not only ominous but that the mere utterance of their names in so negative a context was potentially explosive. Lodge’s unnamed and “insidious” opponents in the immigration wars were almost certainly members of America’s moneyed and influential German Jewish community.

For a quarter of a century, beginning with the moment when Jacob Schiff, the eminent Kuhn, Loeb banker, made a personal plea to Grover Cleveland to veto the literacy test, Lodge, the IRL, and their allies would have to contend with an array of influential organizations dominated by wealthy German Jews.I The first of these groups, choosing a name that explicitly acknowledged the influence of the Immigration Restriction League, called itself the Immigration Protective League. It was followed by the Committee on Civil and Religious Rights of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, the National Liberal Immigration League, the American Jewish Committee, the Friends of Russian Freedom, and many others of similar provenance. Collectively, they composed a formidable and enduring opposition—even though by many measures the bankers, merchants, and other civic leaders who led these groups had more in common with the restrictionists they opposed than with the immigrants they worked so hard to defend. The emergence in the 1890s of organized, wealthy, and well-connected Jews working on behalf of the immigrants presented Lodge and his colleagues with an opposition that few Boston Brahmins had encountered.

Boston had never been particularly unwelcoming to Jews in the years before the new immigration began to accelerate. Credentials seemed to trump origins. When the future Supreme Court justice Louis D. Brandeis, Kentucky born, emerged from Harvard Law School in the late 1870s, he was almost immediately accepted into the city’s legal and social aristocracy. Prescott Hall not only worked with Brandeis on municipal reform efforts (as did Joe Lee) but at one point shared a two-man law practice with a Jewish partner, Edward Adler. The writer and Unitarian minister Edward Everett Hale, a sort of father figure to the liberal branch of Brahmin Boston, expressed credible shock when he encountered mentions of anti-Semitism in the 1880s; it had been utterly unfamiliar to him while growing up in the 1830s.

In New York as in Boston, as well as in a number of other metropolitan centers, the integration of well-educated Jews of central European (and sometimes Sephardic) extraction into elite social and business circles had been routinely accepted for years. In New York, Emma Lazarus’s father was one of the founders of the Knickerbocker Club, which was created in 1871 specifically because the city’s elite considered the membership criteria of the nearby Union Club egregiously lax. Banker Jesse Seligman was a member of the similarly patrician Union League Club for twenty years and one of its officers for fourteen.

But in the early 1890s this tradition of openness was snapped as if by violent reflex. In 1893, while Seligman still served as the Union League’s vice president, his son Theodore was blackballed from membership. “To speak frankly,” said one member, “a majority of the men who frequent the club habitually are opposed to the admission of Hebrews.” The Seligmans had not changed; Theodore, a lawyer, was as well regarded as his father. But two miles downtown, on the swarming pavements of the Lower East Side (soon more densely populated than Bombay) and in the West End of Boston, in South Philadelphia, along Maxwell Street in Chicago, and anywhere else the newcomers from eastern Europe settled, the change in the city’s Jewish population was evident. It was accelerating, and to the members of the Union League and others like them, it was appalling.

The Jews of the Seligmans’ world were guilty not by association with these impoverished aliens—they hardly associated at all with the eastern Europeans—but simply by a common ethnic origin that might have been centuries distant. In Boston even Brandeis began to find himself on the outside of circles that had previously welcomed, or at least tolerated, him. When his law partner was married in 1891, the bride’s family would not allow Brandeis to attend the wedding. Edward Everett Hale’s “amazement,” as he called it, at the sudden appearance in Boston of an anti-Semitism he had not known in his youth did not take into account the demographic kindling that stoked it. When Hale was eighteen, in 1840, there were some one hundred Jews in the city; by 1890 the number had increased two hundredfold.

This seemingly new anti-Semitism among the Protestant upper classes wasn’t entirely a product of the 1890s as much as it was the newly overt expression of an attitude both normative and persistent. A few club memberships and business relationships did not obscure the fact that a finely bred young woman who came of age toward the end of the nineteenth century could refer to a Harvard law professor as “an interesting little man, but very Jew,” or declare that she’d “rather be hung” than attend another “Jew party,” where she had been “appall[ed]” by all the talk of “money, jewels . . . and sables.” In the world of such a young woman, these comments were unremarkable, even unnoticed. But the source of these particular expressions might indicate the ubiquity and persistence of this seemingly inherent anti-Semitism: Eleanor Roosevelt, at the age of thirty-three.

Her biographer, Blanche Wiesen Cook, explains how a paragon of tolerance like Roosevelt could hold such views: her instinctive anti-Semitism, which would evaporate as her life experience deepened, was “a frayed raiment of her generation, class and culture.” Frayed it may have been, but for men and women of her background, that was partly because it was worn so often.II

The irony was that the aristocratic German Jews who offended Roosevelt were comparably offended by the newcomers. Most of the Germans had arrived in the United States before the Civil War and in a couple of generations were well established in their new country. They were educated, cultivated, prosperous—in a formulation offered a century later by novelist Philip Roth in a somewhat different context, they were more accurately described as Jewish Europeans, not European Jews. Many practiced a version of their religion (if they practiced at all) that was light in ritual, modern in outlook; its very name, Reform Judaism, proclaimed an affirmative separation from its ancient roots. The eastern European newcomers were unlettered, unworldly, and by the westernized standards of the German Jews altogether unacceptable. It was as if a royal family suddenly discovered a lost line of unwashed, uncouth kin who embarrassed them by announcing their connection—then horrified them by moving into the palace.

The German Jews were overwhelmed—in numbers, yes, but even more threateningly, in the perception of gentiles. As early as 1884, Cyrus L. Sulzberger (whose son, grandson, great-grandson, and great-great-grandson would all serve as publisher of the New York Times) attributed some of “the prejudice against us in Christian hearts” to “ill-manners” and other forms of disreputable public behavior among the new immigrants. One example offered by the easily bruised Sulzberger: when an immigrant Jew speaks loudly to a restaurant waiter, “he becomes a proper topic for public criticism.” A leading German-language Jewish newspaper referred to the eastern European Jews as “uncouth Asiatics.” Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, founder of Hebrew Union College (Reform Judaism’s first American seminary), said, “We are Americans and they are not. We are Israelites of the nineteenth century in a free country, and they gnaw the bones of past centuries.” The derogatory term “kike” was itself favored by German Jews (some etymologists believe the term originated with them), who used it as a label to distinguish the lowly newcomers from their own, established elite.

The functional definition of “Jew” was mutating right before the eyes of the German Jews, spiraling further away from their own self-image with every steamship that deposited the contents of its steerage compartment on Ellis Island. The cultivated, modern burgher was being supplanted by a strange creature speaking a guttural, alien language, practicing a medieval religion, and beset by “ignorance and depravity,” according to an article in the American Israelite, a leading Reform publication. “Therefore,” the writer concluded, it was “no wonder that a well-defined demand is arising for discrimination in immigration.” The anti-Semitism that kept the younger Seligman out of the Union League was exactly what the German Jews feared, proof that their perceived position of acceptance, even privilege, was imperiled by the swarming “kikes.”

At times the established Jews looked for a safety valve to relieve the pressure. In the early 1880s, in the wake of the czar’s assassination and the resulting pogroms, the first mass inflow of Russian Jews induced a self-protective reaction. The Hebrew Emigrant Aid Society (not to be confused with the very different and somewhat later Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society) was formed to assist the newcomers by sending as many as possible away from New York as quickly as possible. This effort to “receive [and] disperse” led to the creation of small colonies of Russian Jews in the somewhat plausible southern New Jersey town of Vineland, and in such unlikely locales as the metropolis of Cotopaxi, a hamlet 150 miles south of Denver in central Colorado. In all, HEAS and its affiliates dispatched Yiddish-speaking Jews to sixteen different settlements scattered across the vast country, the most distant one, in Oregon, bearing the wishful name (if you had been driven from Ukraine) New Odessa.

The federal government provided army tents for the Vineland settlers and gave each of the seventeen families shipped to Cotopaxi the 160 acres customarily allotted to homesteaders. HEAS, for its part, gave them assistance in New York, train fare west, some seed money for the colonies, and good riddance. As Augustus A. Levey, the secretary of HEAS, saw it, there was little choice. “The ineffaceable marks of permanent pauperism” scarred the new immigrants, Levey wrote. The inevitable crimes that would be committed by “these wretches,” he continued, “will throw obloquy over our race.” The best place for them, in a word, was elsewhere.

Levey and his colleagues in New York were not outliers. Jewish leaders in Cleveland and Milwaukee announced that they would not tolerate the importation of additional eastern European Jews to their cities. In Boston, wish became action: the Hebrew Observer reported that the local branch of HEAS met 415 Russian Jews at the docks and “promptly [shipped] them back to New York as soon as they arrived.” An additional 75, suffering in penury through the brutal winter of 1882–3, declared that they preferred to return to Russia. When offers to pick up the tab for their repatriation came from the Boston Provident Association and the Board of Charities—de facto subsidiaries of Boston’s native-born elite—the established German Jews of Boston finally realized the hollowness of their own deeply held belief that they were different from the easterners. What mattered was not what they believed, but what the gentiles believed. And a growing portion of the most influential gentiles thought there was very little difference at all.

The conscious resettlement of Jewish immigrants away from the East Coast would continue throughout the period of greatest immigration. United Hebrew Charities, the most firmly established of the German Jewish philanthropies, led the effort, shooing many of the refugees westward—and over a period of years sending more than 7,500 of them (mostly the unemployed and their families) back to Russia. As late as 1905 the influential rabbi Jacob Voorsanger of Temple Emanu-El in San Francisco thundered that neither “sympathy nor sentiment of affection generated by kinship . . . should prevent us from appreciating the justice of cutting off Jewish immigration.” Jacob Schiff continued to support the immigration of the Russian Jews but in 1907 he subsidized a program that redirected German ships to the port of Galveston. Over the next seven years some 10,000 eastern European Jews found themselves first touching American soil in Texas. Once there, they were distributed throughout the West and Midwest, their final destinations usually determined by a specific community’s need: if Kansas City lacked a kosher butcher, for instance, Schiff’s allies in Galveston would send the next one off the boat to Kansas City. This didn’t always work out to everyone’s satisfaction. In his Galveston: Ellis Island of the West, historian Bernard Marinbach relates the story of an immigrant who was dispatched to Sioux City, Iowa. Not long after he arrived he wrote to his wife in Russia, begging her to sell everything they owned and send him train fare to New York.

Eventually the organized German Jewish communities in New York and other large American cities assumed a new position regarding their eastern European relations. They really had no choice. To the wealthy gentiles of the period, the distance separating the German Jews and the eastern newcomers grew disappearingly small, and as the language of the anti-immigrationist campaign became increasingly and explosively racialized, the German Jews were wounded by the shrapnel. Most were compelled to become advocates for those they had previously scorned. Mount Sinai Hospital, which the German immigrants had established in New York in the middle of the nineteenth century (and formally named, at first, Jews’ Hospital), finally agreed to serve kosher meals. In New York and Philadelphia, German Jews initiated the kehillah movement, a conscious effort to bring together the two distinct Jewish communities. Political alliances between uptown and downtown began to sprout as well. Cyrus Sulzberger, who had earlier attributed anti-Jewish prejudice to the crude manners of the immigrants, would in time tell a congressional committee, “Large numbers of Jewish immigrants have arrived in this country since 1880. [Instead of] pulling down our standards of living, they have done the reverse.”

* * *

IN SEPTEMBER 1901, two years after the defeated and disheartened Immigration Restriction League shut down its operations, it was brought back to life by a bullet. The man who shot William McKinley at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, Leon Czolgosz, was more than a murderer: he was a declared anarchist, and by his very name (if you thought about such things) patently un-American. Never mind that Czolgosz was a natural-born citizen who first drew breath in Alpena, Michigan, in 1873. Two weeks after the president died, four men of the IRL felt the urge to gather in Prescott Hall’s office to resume the efforts they had suspended after Congress’s failure to enact Henry Cabot Lodge’s literacy test during McKinley’s presidency.

They had reason to be hopeful. Hadn’t Theodore Roosevelt, the new president, once told Lodge that the net effect of Cleveland’s veto of the literacy test was “to injure the country as much as he possibly could”? Before the year was out, Roosevelt would open his annual message to Congress with a eulogy to McKinley, follow that with an attack on Czolgosz and other anarchists, and ask the House and Senate to enact “a careful and not merely perfunctory educational test” to keep out immigrants who did not possess “some intelligent capacity to appreciate American institutions and act sanely as American citizens.”

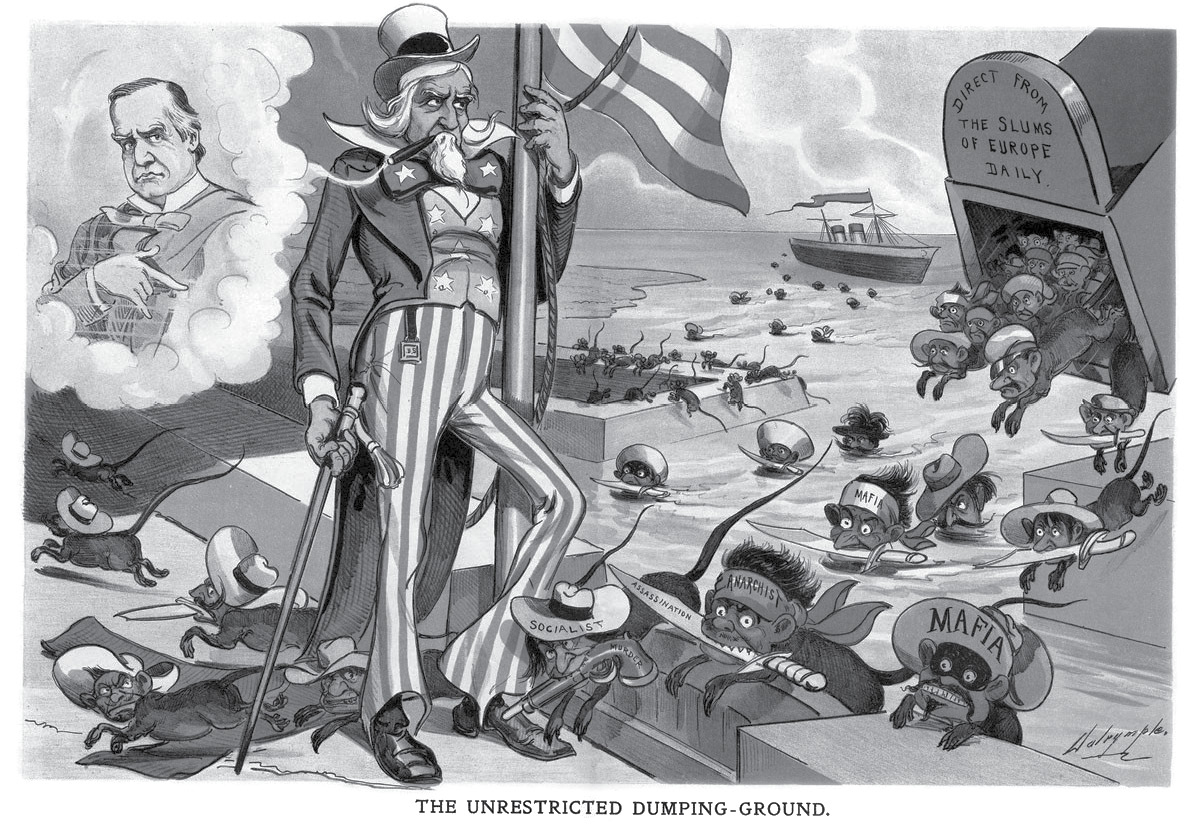

Two years after the assassination of William McKinley (upper left), Judge cartoonist Louis Dalrymple portrayed the new immigrants as verminous, murderous, and (by implication) complicit.

He sounded like his best friend, Lodge.

Throughout much of his public life, Theodore Roosevelt beat the drum for what was essentially a eugenic view of American progress. Because few men of the era beat a drum with quite the vigor or virtuosity that Roosevelt brought to the task, he made a substantial contribution to the growing acceptance of Galtonian thinking in the United States even if he may not have fully recognized its potential as a weapon in the immigration wars.

Like his niece Eleanor, Roosevelt generally wore his racial views as if they were a suit of clothes inherited from an older sibling: they had grown threadbare with time, they fit him loosely, and he rarely appeared in them in public. But whatever biases he had inhaled in his privileged New York childhood were amplified from the moment he arrived at Harvard as a seventeen-year-old in 1876. He met Henry Cabot Lodge in the very thin atmosphere of the inalterably Protestant Porcellian Club, a Harvard institution so undisturbed in its exclusiveness that a man like Lodge, who had graduated four years before Roosevelt, could remain comfortable there the rest of his life. Through Lodge, Roosevelt was befriended by Thomas Bailey Aldrich, who had sung of the “Unguarded Gates.” Among the teachers who most influenced him was Nathaniel Shaler, a widely admired Harvard professor of geology (and nominal officer of the Immigration Restriction League). Based on his experience as “an observant foot traveler” in Europe, Shaler believed that just as it would take “some centuries of sore trial” for the typical American to revert to the living standards of an eastern European peasant, it was likely true that it would take equivalent centuries for the latter to rise to the status of the former. Also like niece Eleanor, Uncle Theodore recoiled from the “Jew bankers” he encountered at a party, whom he considered “gold-ridden” and who threatened the onset of a “usurer-mastered future.”

But when Roosevelt made Oscar Straus of New York the nation’s first Jewish cabinet member in 1906, Straus would recall, the president told him he had put him in the job (secretary of commerce and labor) “to show Russia and some other countries what we think of Jews in this country.” Early in his presidency Roosevelt visited Ellis Island, engaged with several of the new arrivals, and showed genuine concern for their welfare (he was particularly upset that doctors examining immigrants for trachoma did not wash their hands thoroughly). In the opening paragraph of his autobiography he referred with a sort of mischievous glee to the first Roosevelt in the New World, who arrived in New Amsterdam in 1644, as “a ‘settler’—the euphemistic name,” he wrote, “for an immigrant who came over in the steerage of a sailing ship in the seventeenth century, instead of the steerage of a steamer in the nineteenth century.”

Still, the Roosevelt who threw himself delightedly into the bubbling stew that was America at the turn of the last century—who as New York police commissioner had given a notoriously anti-Semitic German politician visiting the city an all-Jewish detachment of bodyguards, and who invited Booker T. Washington to dinner at the White House—was, inescapably, a prisoner of his own class. “Mr. Roosevelt is always talking about his policies but he is discreetly silent about his principles,” Mark Twain said, and some of those unarticulated principles lay unseen in a psychic fortress of class and race supremacy that could never be fully breached.

In the private life of the Roosevelt family, this class isolation was expressed most clearly in his wife’s attitudes. Edith required her sons to research the family origins of any new friends; shunned anyone who was not, she said, “de notre monde”; and with breathtaking cruelty said of her servants, “If they had our brains, they’d have our place.” Her husband was far more open-minded but was equally persuaded that people like him, his friends, and his family were innately superior. From a world of such sequestered self-regard came a nativist attitude that Roosevelt considered patriotic. Despite all of his demotic (if not exactly democratic) impulses, he was determined to preserve the position of the Anglo-Saxon aristocracy, which he considered essential to the nation’s success, even its survival. Several years before he became president he expressed the belief that the preservation of his class would come only from its members’ commitment to large families (he was himself a father of six). It was a worldwide problem; he fretted about the southern Italians, whom he called “the most fecund and the least desirable population of Europe,” and came to fear that the Hawaii planters’ importation of Asian laborers would lead to “the extinguishment of [the planters’] blood.” If “native Americans”III of the northeastern states were to maintain their position, it was essential that they reproduce more rapidly than the proliferating immigrants and thus emerge triumphant from what Roosevelt memorably called “the warfare of the cradle.”

Roosevelt was not a hater, steeped in the toxic prejudice that drenched so many around him. He would in time become an enthusiastic fan of Israel Zangwill’s play The Melting Pot, which bequeathed that resonant phrase and the concept it represented to the American consciousness. But as president he was fearful. The declining birthrate panicked him, and he spoke of it repeatedly. Married couples who engaged in “willful sterility”—that is, who chose not to have children—deserved “the severest of all condemnations.” In a speech to the National Congress of Mothers in 1905 he attributed a couple’s decision not to have children to “viciousness, coldness, shallow-heartedness, self-indulgence,” and other similarly repugnant qualities. Even after he left the White House, Roosevelt would not let go of what he truly believed to be a question of existential consequence. It was those who did their patriotic duty by having four or more children upon whom “the whole future of the Nation, the whole future of civilization rests.”

Throughout his public years of pounding lecterns, tabletops, and the ears of his listeners, Roosevelt was usually careful not to distinguish between segments of the population while he searched desperately for those who would save the world. “I, for one, would heartily throw in my fate with the men of alien stock who [were having families of sufficient size and] were true to the old American principles,” he wrote at one point, “rather than with the men of the old American stock” who were not doing their reproductive duty. Yet Roosevelt hinted at something different when he was more certain of his audience. He may have moved beyond the idea he’d expressed to his pal Henry Cabot Lodge in 1896—“I’d like to see a white man now and then,” he’d told Lodge, whose company he missed.IV But in 1908, as his presidency neared its end, his position was nonetheless clear. To Stanford president David Starr Jordan—who just happened to be chairman of the eugenics committee of the American Breeders Association—Roosevelt confessed that he was “melancholy,” because “the best men” were “content that the citizens of the future come from the loins of others.”

If novelist Owen Wister, his friend of four decades, can be believed, Roosevelt did not hedge at all in private conversation. A decade after Roosevelt’s death, Wister recalled a comment he had once made about the birthrate. “It’s simply a question of the multiplication table,” Roosevelt had said, in Wister’s recollection. “If all our nice friends in Beacon Street, and Newport, and Fifth Avenue, and Philadelphia, have one child, or no child at all, while all the Finnegans, Hooligans, Antonios, Mandelbaums and Rabinskis have eight, or nine, or ten—it’s simply a question of the multiplication table. How are you going to get away from it?”

“It” could have been defined by a term Roosevelt began using in 1902 and that soon entered the national vocabulary in the debate over immigration. As vivid and as potent a phrase as his “warfare of the cradle” might have been, it paled in comparison to this one: “race suicide.”

But what, exactly, did Roosevelt mean by “race”?

“Of all vulgar modes of escaping from the consideration of the effects of social influences on the human mind,” John Stuart Mill wrote in 1848, “the most vulgar is that attributing the diversities of conduct and character to inherent natural influences.” Vulgar it may have been, but to the race theorists of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries it was irresistible: if a person could attribute his virtues to his pedigree, he was beyond challenge. The obverse was an even more powerful notion, for without the proper pedigree a man was ipso facto inferior.

Why the stork on this popular postcard saw reason to be calm is unclear, but his imaginings no doubt coincided with Roosevelt’s fondest dreams, which W. A. Rogers illustrated in a 1905 cartoon (facing page).

In the same year that Mill wrote, the revolutions that rocked Europe dislodged an idea from the frozen set of prejudices that encased the life of Count Arthur de Gobineau. A French nobleman, royalist, novelist, diplomat, and—proudly—racist, Gobineau was gripped by two unshakable convictions: that the world had started to come apart with the French Revolution, and that “race” was mankind’s defining issue. In 1855 he bequeathed to generations of racists to come his four-volume Essay on the Inequality of Human Races, the foundational text of what would become known as scientific racism. Gobineau’s supporting evidence was scientifically negligible, his logic broken-backed. But his narrative talent was vigorous, and for those eager to be persuaded, it was a gift. One of his earliest fans was Richard Wagner, whose wife wrote to Gobineau to say that “my husband is quite at your service, always reading The Inequality of Human Races when he is not at work” on his operas. And a few decades later one of Wagner’s own enthusiasts, stuck in a Bavarian prison, embraced Gobineau with comparable enthusiasm: Mein Kampf is awash with Gobineau’s ideas.

In his early thirties Gobineau was for a brief time secretary to Alexis de Tocqueville. In 1853 that great student of democracy told Gobineau that “one is fascinated both by what you could be and by what one fears you may become.” Ten years later, having read the Essay, Tocqueville’s fears were realized: he told Gobineau that his ideas were not only erroneous but “very pernicious.” The Essay delineated in excruciating detail (and with highly suspect authority) a world of three races made virtuous only by the white: “Everywhere the white races have taken the initiative, everywhere they have brought civilization to the others,” he insisted. Without the white, the black and yellow bordered on the worthless. Only by segregating itself from the black and yellow could the white remain pure. (Interestingly, this belief led him to a certain ambivalence regarding slavery: the proximity of white and black inevitably led to miscegenation.) He did acknowledge that a certain amount of race mixing was necessary, or at least it had been long ago—without a little bit of black stirred in, he wrote, whites would never have been able to achieve “artistic genius.” But, like the peril faced by a chemist brewing an explosive concoction in his lab, the quantity had to be just so much and not a droplet more. It was this sort of mixing, Gobineau believed, that allowed Greece to thrive and Rome to fall. It also created the various subraces (which would later be called ethnic groups or perhaps nationalities) that Gobineau and his followers would begin to sort, classify, and rank as if they were tomatoes entered in an agricultural fair.

Nearly a century after Gobineau (and for scientific racism it was quite a century), modern genetics inflicted fatal wounds on race theory, and by the time the Human Genome was sequenced in the 1990s, long-held concepts of race were all but demolished. Of the roughly twenty thousand protein-coding genes allocated to each human, it turned out that a relative handful manifest themselves in what are today generally considered the signifiers of race—skin color, hair texture, nose shape, and so on. We can accurately identify people by color, or language, or nationality. Yet as genetic signifiers for what lies beneath the visible surface, these characteristics are essentially meaningless. As Thomas F. Gossett made clear in his invaluable Race: The History of an Idea in America, attempts to sort Europeans by race are “anthropologically unintelligible.”

But in the nineteenth century, for those who wished to examine the world through a racial microscope, the product of their efforts soon became dogma, independent of Gobineau’s convulsive hatred. “Racial” distinctions were parsed with robust enthusiasm and exquisite (if widely varying) precision. Gossett notes that Charles Darwin’s great ally Thomas Huxley identified four races, the influential German biologist Ernst Haeckel (who coined “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny”) counted thirty-six, and the French anthropologist Joseph Deniker enumerated seventeen races that could be subdivided into thirty distinct types. Like so much assertion, speculation, and theory issued forth in the last decades of the nineteenth century, to some degree this ferment of racial analysis was a direct, if almost certainly unintended, product of the Darwinian revolution. Once you establish that not everyone is descended from Adam and Eve—and thus not genetically related to one another—anything goes: racial differences, racial hierarchies, racial hatred.

The century’s discussion of race culminated in two books published in 1899, both of which would play major roles in the race controversies of the century ahead. The first, Houston Stewart Chamberlain’s Foundations of the Nineteenth Century, would become, like Gobineau’s Essay (which it cites repeatedly), an essential text of Nazi ideology. Chamberlain was a well-off Englishman (though not related to the political Chamberlain family) who moved to Germany at age thirty, drawn by his passion for the music and, even more, the racial ideology of Richard Wagner. Chamberlain may not have written at Gobineau’s length (Foundations was a mere two volumes), but he outdid the Frenchman in his attachment to Wagner: not only did Chamberlain write his biography, he eventually married the composer’s daughter and settled in the Bavarian city of Bayreuth, the beating heart of all things Wagnerian.

No wonder: in its loopy mythologizing of Teutonic virtue, Foundations is nearly as complex and as opaque as the Ring Cycle. Anti-Semitic, anti-Catholic, fanatically pro-Aryan (a term summoned into its modern usage by Gobineau), it also became a text so endearing to Adolf Hitler that in 1927 he and Joseph Goebbels paid homage to Chamberlain by visiting him on his deathbed, and Hitler returned for the funeral. For present purposes, let one of its sentences serve as a summary of its main argument: “Physically and mentally the Aryans are pre-eminent among all peoples; for that reason they are by right . . . the lords of the world.”V If any great historical figure was not Teutonic, Chamberlain found a way to make him one: “That Dante is Germanic [is] so clear from his personality and his work that proof of it is absolutely superfluous.” (Marco Polo, Francis of Assisi, and Galileo all made the cut as well.) The book was a huge bestseller in its original German (Chamberlain adopted the language as his own, with the same enthusiasm he brought to his alliance with the Volk), and when translated into English it carried an approving introduction by Lord Redesdale, grandfather of the famous Mitford sisters. Its other British fans included George Bernard Shaw (who called it “a masterpiece of really scientific history”) and, Redesdale told Chamberlain, Winston Churchill. When it was finally published in the United States in 1910, Theodore Roosevelt, by then ex-president, savaged it. But it did find a particularly enthusiastic supporter in Prescott Hall, who recommended it to Joe Lee as “the most delightful summer reading.” On receiving Hall’s letter, Lee lifted his pen to scrawl one word across its top: “Get.”

But as provocative as Foundations was, and as comforting to those looking for historical justifications (however fanciful) for their preconceptions, beyond the most intensely xenophobic circles, in the United States it was not as influential as the other signal book on race that came out in 1899. That was William Z. Ripley’s The Races of Europe, which by its very title helped firm up the notion that “white” was not a race, but merely a convenient rubric for a collection of distinct races. Unlike Gobineau and Chamberlain, Ripley was a genuine scholar (even if his scholarship was somewhat diluted by his range of subjects: an economist by training, he at various times taught sociology, anthropology, and physical geography at MIT, Columbia, and Harvard). He also was not (or, perhaps, especially) an anti-Semite, a racist, or a crank; Gobineau appears nowhere in his book’s six hundred–plus pages. Although much of his work doesn’t hold up under twenty-first-century standards, Ripley was careful. He dismantled the existence of an Aryan race in seven well-informed, tightly argued pages. On the very first page of the book he warned readers not to think of race as a factor entirely independent of “social contact,” indicating that he believed nature and nurture were irretrievably intertwined. Near the book’s end he explained that most “social phenomena” we associate with one particular race—in this case the “Alpines”—arise “not [from] racial proclivities” but from “geographical and social isolation.”

Still, Ripley did find the Alpines distinct—one of three separate European races, along with the Teutonic and the Mediterranean; he excluded Jews entirely from his European triumvirate and placed them in a separate category. The Teutonics were tall, blond, and blue-eyed; the Alpines shorter and somewhat darker; the Mediterraneans slim and darker still. He didn’t rank them qualitatively. He recognized the extent of European cross-fertilization and its consequent effects on any effort to identify “pure” members of each race. Like John Stuart Mill, Ripley considered the attribution of specific “social, political, or economic virtues or ills” to any specific race “vulgar.” But by seeming to establish the very concept of different European races, Ripley effectively sanctioned the central arguments of two groups that would later draw on his work for both sustenance and justification: the eugenicists and the immigration restrictionists.

But that was still a decade into the future. In 1902 “race” was used as convenient shorthand. In the American context, when people like Theodore Roosevelt spoke of the future of “the race” or “our race,” they were almost always speaking of white Americans of native birth and parentage.

“William does not leave as many children as ’Tonio,” wrote Edward A. Ross in 1914, “because he will not huddle his family into one room, eat macaroni off a bare board, work his wife barefoot in the field, and keep his children weeding onions instead of at school.” It’s no surprise that the man who first introduced the phrase “race suicide” into public discussion in 1901 would later be the author of this remarkable statement. By the time Ross thus reduced the more than two million Italians who had immigrated to the United States in the preceding decade to macaroni-eating exploiters of wives and children, he had been peddling his ideas of racial inferiority for far longer than a decade. This was the same Ross who, writing of Chinese laborers just a few years before he trained his focus on William and ’Tonio, had asserted that “Reilly can outdo Ah-San, but Ah-San can underlive Reilly.” Originality was not a trait he particularly valued.

But provocation was. Ross was a scholar, an ideologue, a publicist, an aphorist, and something of an agitator. A solid six feet six inches tall, his strong cheekbones framing a substantial mustache, he stood out in any crowd not just because of his singular appearance but because of a booming self-confidence that was always insuperable, often insufferable, and that somehow managed to both emphasize his imposing stature and amplify his thunderous voice. The product of a midwestern farm boyhood that had been wrenched out of shape by the death of his parents before he turned ten, Ross emerged from the guardianship of three different families to pursue an academic life, receiving his PhD at Johns Hopkins (where Woodrow Wilson was one of his teachers) at twenty-four. In an autobiography published when he was seventy, he wrote that “there may come a time in the career of every sociologist when it is his solemn duty to raise hell,” and in his own case he had found that time ten years into his career, when he was teaching at Stanford. Addressing an audience of labor leaders, he condemned the Central Pacific Railroad for hiring Chinese workers. The fact that his salary effectively originated with the Central Pacific—it was the source of the fortune that founded Stanford—did not deter Ross; given his brassy self-assurance and his appetite for attention, it could have been the impetus that drove him to speak out. Jane Lathrop Stanford, widow of the university’s benefactor and by 1900 its sole trustee, demanded Ross’s firing.VI When university officials capitulated, thus confirming what Ross called the “hollowness” at the center of the relationship of scholar and patron, he was delighted. His case provoked the sympathetic resignations of several other Stanford faculty members. And in time he could take justifiable pride in his role in the advent of the American system of academic tenure and the formation of the American Association of University Professors, which adopted the defense of academic freedom as its primary mandate.

Ross’s dismissal also put him firmly on the national stage. From Stanford he went to the University of Nebraska and then to the University of Wisconsin, where he happily took on the role of prairie radical, allied with the archprogressive governor Robert M. La Follette. He advocated for labor unions, opposed “the ruthless practices of business men,” supported the socialist presidential candidacy of Eugene V. Debs, and at seventy-four would achieve the pinnacle of his public life when he was elected national chairman of the American Civil Liberties Union. Ross’s books sold hundreds of thousands of copies, and he agreeably (if a little too smugly) made one of them, Capsules of Social Wisdom, “available in attractively bound reprints, numbered and paged suitable for a gift.” The “capsules” consisted of a lifetime’s gathering of some six hundred maxims, folk dicta, and self-evidencies along the uninspired lines of “A few scorn riches, but no one scorns good repute!”

Such chestnuts didn’t have quite the heft of “race suicide,” which Ross first unveiled in a 1901 speech. “There is no bloodshed, no violence, no assault of the race that waxes upon the race that wanes,” Ross told the annual meeting of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. “The higher race quietly and unmurmuringly eliminates itself rather than endure individually the bitter competition it has failed to ward off from itself by collective action.” Like many progressives of the day—like, for instance, Joe Lee—Ross had no difficulty reconciling his ethnic intolerance with his quasi-socialist views on the role and responsibilities of government; the latter did not click into place until the ferry bound for the Manhattan piers departed Ellis Island. Once immigrants were admitted, Ross and Lee believed, government and charitable institutions had the obligation to “Americanize” them. As historian Mike Wallace has written, “ ‘Progressive’ was a fuzzy term for an ambivalent politics.”

But for Ross, there was a gap between the wish and the act: he was not convinced that Americanization was possible. After establishing his eminence in both the academic world and the political sphere, Ross won greater fame with a series of articles and books expressing his belief that many of the immigrants coming into the United States early in the twentieth century were members of “the lower races”—in truth, barely human. Even when immigrants were “washed and combed” in their Sunday best, he wrote, the observer could not help but be repelled by the “hirsute, low-browed, big-faced persons of obviously low mentality.” These “oxlike” people, he insisted, “clearly belong in skins, in wattled huts at the close of the Great Ice Age.” What the phrase “race suicide” may have meant to Theodore Roosevelt, who popularized it, was somewhat vague, at least to those not in his immediate circle. To Ross, who first brought it to Roosevelt’s attention, there could be no doubt what it meant. “A people that has no more respect for its ancestors and no more pride of race than this,” he concluded, “deserves the extinction that surely awaits it.”VII

The idea of the reproductively deficient American of northwestern European origin—the everyman “William” who couldn’t keep up with progeny-producing, macaroni-eating “ ’Tonio”—descended directly from Francis Walker, the MIT president who had famously deprecated the southeastern Europeans as “beaten men of beaten races.” Walker said that the reason for the tumbling birthrate among native-born Americans was obvious: Why would the previously dominant “races” bring children into a world degraded by immigrants who were “unfit to be members of any decent community”? It was a practical choice as well: How could the children of the native-born possibly hope to compete with men willing to work for pennies and to live like animals?

But for all his dismissive, vituperative, even hate-filled assaults on the southern and eastern European immigrants (“vast masses of filth . . . living like swine”), Walker never suggested that the “beaten races” were biologically different; they had been “brutalized,” he argued, by social, political, and historical circumstances that had rendered them inferior. He even acknowledged that the “great majority” of the immigrants were unobjectionable. His was more an economic argument than a racial one.

Ross drew no such distinctions. “The superiority of a race cannot be preserved,” he declared in 1904, “without pride of blood.” If his bellowing italics failed to make the point, he spelled out what he felt was required: “an uncompromising attitude toward the lower races.”

According to Owen Wister, Ross’s notion of “race suicide” was associated with Roosevelt just as much as “Speak softly and carry a big stick,” and its implicit call to action was echoed in the popular press. No less a figure than the black scholar and activist W. E. B. Du Bois would adapt it for his own use, invoking the term to criticize the reproductive efforts of “educated and careful” families who were having “few or no children” (he also argued that black people needed to “train and breed for brains, for efficiency, for beauty”). Race suicide also became a subject of academic papers produced, inevitably, by those who had the most to lose. One such study, in the Yale Alumni Weekly, rolled out an armamentarium of tables, graphs, and pie charts to demonstrate that the average married graduate in the Yale classes of 1867–1886 had but 2.02 children. Once their unmarried classmates were factored in, added a Boston commentator gravely, it was obvious that they “had failed to reproduce themselves.”

The apotheosis of this sort of thinking would wait until 1916, when a series of articles on race suicide would provoke a wealthy Harvard-trained physician named John C. Phillips to explore the crisis at his alma mater (Phillips also happened to be an avowed eugenicist, a devoted member of the Immigration Restriction League, and a few years later, Joe Lee’s neighbor on Mount Vernon Street). Phillips’s study revealed the discouraging news that the situation was not much better in Cambridge than in New Haven; between 1850 and 1890, average family size among Harvard alumni had dropped 30 percent. It also indicated that the women of Wellesley College were having only 0.86 children per graduate, which Phillips considered “pathetic.” And, in the most brutal of these statistical blows to Brahmin preeminence, one calculation indicated that the continuing failure to reproduce in robust numbers would mean that 1,000 Harvard graduates in the class of 1916 would have but 50 living descendants in 2116. Lewis Terman, whose influential The Measurement of Intelligence was published the same year as Phillips’s study, invoked those fate-freighted numbers several years later, and delivered this equally unsubstantiated clincher: at current rates of reproduction, while the number of Harvard progeny will have dropped from 1,000 to 50, “1,000 South Italians will have multiplied to 100,000.”

Joe Lee would make use of the concept of race suicide with a question directed to the Boston ladies bountiful who were active in social services: “When you are helping the dear Roumanian lady who has fifteen children and the dear Italian ditto who has 25,” asked Lee, “what is becoming of your children you are not having?”

* * *

THE “DEAR ITALIAN DITTO,” fear of “a Dago nation,” “wop”—the terms tossed about in the correspondence of the anti-immigrationists or freely invoked in congressional debate were mere hints of a reality too rarely acknowledged in memoirs of the period: that the eastern European Jews were not the largest immigrant group—nor, at first, the people most despised by the nativists. Both distinctions belonged to the Italians, who had begun to arrive in large numbers in the 1880s. In 1850, the year Henry Cabot Lodge was born, 431 Italians left their homeland for the United States. By 1887, the year Lodge entered Congress, the annual number had rocketed to 47,622. It inched up to 59,431 ten years later, when the literacy test was murdered by Grover Cleveland’s pen. And a decade after that, fully 285,731 Italians entered the States in a single year. Overall, in the first decade of the twentieth century, more than two million Italians arrived on American shores, most of them from Sicily and the south, most of them desperately poor, and by one estimate 68 percent of them illiterate.

To the American-born patriciate of Boston, New York, and other cities, the Italians were, unlike the Jews, completely incomprehensible. In his 1880 novel, Democracy, written before he was fully seized by his deranged anti-Semitism, Henry Adams created the wealthy German Jewish Schneidekoupon family. Adams saw them as largely unexceptionable members of Washington’s highest social realms, intimates of the book’s admirable heroine.VIII Prescott Hall, whose anti-Semitism would become the primary engine of his encompassing xenophobia, did not let it deter him from forging his partnership with Edward Adler. Joe Lee admired Louis Brandeis greatly, had productive relationships on public matters of mutual interest with both Brandeis and Felix Frankfurter, and when he ran for a seat on the Boston School Committee, his running mate was a Jewish lawyer named Moses H. Lourie, whom he considered “a thoroughly straight and high-minded and very intelligent man.” The fact that a few Jews were acceptable (at least until they were not) demonstrated to many of the most ardent restrictionists that, as a people, they were somewhat responsive to the civilizing effects of education, culture, and material success. They could be cultivated; they could be well-spoken; they were capable of learning which fork to use.

But for all practical purposes, the only Italians the patricians encountered on even a semiregular basis were fruit peddlers and bootblacks. Secretary of State Elihu Root, who had staunchly supported Theodore Seligman’s application to join the Union League Club, compared recent immigration from southern Europe to “barbarian invasions.” David Starr Jordan said that “there is not one in a thousand from Naples or Sicily that is not a burden on America.” At one point retired Supreme Court justice Henry Billings Brown, writing from his eighteen-room Flemish Renaissance mansion near Washington’s Dupont Circle, called for a complete ban on immigration from Sicily and Calabria. In 1906 a Washington Post editorial writer stooped to acknowledge that “there is no better agricultural laboring class in the whole world than the real Latin peasantry.” But, he continued, 90 percent of the Italians coming to the United States were “the degenerate spawn of the Asiatic hordes which, long centuries ago, overran the shores of the Mediterranean.” They were coming to America “to cut throats, throw dynamite, and conduct labor riots and assassination.”IX Even those who managed through talent and hard work to penetrate the redoubts of the privileged were ridiculed. In a novel published in 1902 (one year after his enormous success with The Virginian), Owen Wister described the “shiny little eyes . . . furtive and antagonistic” of an Italian student at Harvard. “I don’t think Oscar owns a bath,” one of his classmates says with a smirk.

Inevitably, as the downtown Jews struggled to rise, some of them sought to consign other groups, including the Italians, to lower rungs of the ladder. The anti-immigration movement, said the Russian-born physician, economist, and social reformer I. M. Rubinow, was not anti-Jewish; it was anti-Irish, anti-Polish, anti-Italian. “The Americans may be right,” wrote Rubinow; those other groups, he insisted, “are culturally inferior.” In sectors of the labor movement Italians who weren’t despised as strikebreakers were nonetheless seen as directly responsible for low wages. This was particularly so in the case of the so-called birds of passage—laborers who would come for several months, then return home with their savings. In the period of greatest immigration, for every ten Italian immigrants who came to the United States there were seven returning to their homeland. When Jacob Riis wrote with a discomfiting condescension that the Italian immigrant in New York was content to “live in a pig-sty,” he may have been describing circumstances tolerable only to men intent on saving every conceivable penny to take back home to their desperately poor families. But even at his most sympathetic, Riis slapped with one hand while he embraced with the other: “With all his conspicuous faults, the swarthy Italian immigrant has his redeeming traits. He is as honest as he is hot-headed.” Joe Lee dismissed an assertion that the “inborn suavity” of the Italians would improve the nation’s manners. Because “this inborn suavity takes the form of sticking a stiletto into your friends and enemies and acquaintances,” he wrote, “it seems to me that it is an undesirable substitute” for American etiquette. This wasn’t a private communication. It was the heart of a letter to the editor published in a Boston daily.

The Italian immigrants were not without their advocates. But their fellow countrymen hadn’t nearly the political or financial might of the German Jews, many of whom had arrived in the United States endowed with both money and education, and most of whom had been in the country for decades. The Italian-born and Naples-trained physician Antonio Stella—older brother of the futurist painter Joseph Stella—was instrumental in a number of efforts to help the newcomers, engaging in issues related to public health (he was particularly active in the battle against tuberculosis, which was often endemic in the slums) and public perception (notably with his proudly pro-immigrant book, Some Aspects of Italian Immigration). Enrico Caruso—as it happens, Stella was the great tenor’s personal physician—was among prominent figures who supported the Society for Italian Immigrants. Sympathetic assistance came from such surprising groups as the Connecticut chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution, who were supporting a principle not dissimilar from some of Joe Lee’s charitable efforts: whatever one’s attitudes toward the foreigners, once they were here, it was necessary to educate them. Toward this end, the DAR commissioned immigration advocate John Foster Carr to write a series of how-to-be-American books directed at Italians, Jews, and Poles. Guida degli Stati Uniti per L’Immigrante Italiano provided some basic American history and geography along with useful explanations of tasks as relatively complex as opening a bank account and as basic as personal hygiene (“Bathe the whole body once every day,” Carr shouted in boldface typeX). Carr’s book also included the encouragement to get out of town: “Do not be deceived by the good wages that are often paid in large cities,” read an official translation. “Thousands of Italians have made extraordinary successes here in farming and gardening.”

A more thoroughly empathetic version of Americanization, as the civilizing process became known, was rooted in the settlement house movement. These all-purpose educational-recreational-social-cultural-job-training-and-sometimes-medical agencies were usually funded by prosperous citizens who recognized the need to provide services to the new immigrants crowding their cities. One such was the Civic Service House in Boston, founded by Pauline Agassiz Shaw, whose husband was an Adams and whose father was the famous (and immovably anti-Darwinian) Harvard naturalist Louis Agassiz. Jane Addams used an inheritance from her wealthy father to open her famous Hull House in Chicago in 1889, and six years later Jacob Schiff financed the Henry Street Settlement on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, where Lillian Wald started the Visiting Nurse movement. Across the East River, the Italian Settlement opened its doors in 1901 in a building directly beneath the vaulting span of the Brooklyn Bridge.

The Italian Settlement dedicated itself to the area’s teeming crowds of Neapolitans, Sicilians, and Calabrians. The founding director remained in his job for forty-two years, so devoted to the neighborhood’s immigrants that in 1908 he traveled to Sicily in the wake of the merciless Messina earthquake that killed some 25,000 people. He carried with him a list of 160 people to look for—relatives of his clients in Brooklyn—but in the tumult of the ruinous disaster he could locate only 67 of them. To those he gave aid; for the rest, he could only mourn. But, he recalled afterward, “our experience with south Italians in this time of crisis . . . deepened our sense of their good natural qualities and their promise of their value as citizens among us.”XI

The Italian Settlement’s director was necessarily engaged with the immigration politics of the era. He opposed the literacy test and any increase in the head tax charged each arriving immigrant. The nation’s “duty to the immigrant,” he believed, was absolute. But at one point, the director did suffer a bout of despair. “We have neglected the immigrant,” he wrote to his brother. “We have put upon him burdens he was unable to bear and responsibilities which he never carried out in his own land, and when the result of our negligence and indifference and infidelity comes home to us, we do not decry our own deficiency, but put all the blame on him instead of sharing our part of it.”

The director of the Italian Settlement was William E. Davenport, the Connecticut-born son of a prominent Brooklyn family. His brother Charles ran a biological laboratory on Long Island.

I. Many were not specifically from Germany, but came from Austria, Bohemia, and other parts of central Europe. The useful modifier “German” is less descriptive of their disparate nationalities than of their shared language and culture. The eastern Europeans, of course, spoke Yiddish.

II. The Eleanor Roosevelt more familiar to modern readers was expressed in her work in a Lower East Side settlement house in the early 1900s and her resistance to a cousin’s entreaty to leave her job and come to Newport lest she contract “an immigrant’s disease.” The “very Jew” professor was Felix Frankfurter, twenty years before Eleanor’s husband appointed him to the Supreme Court.

III. Long before it was used to describe people descended from North America’s aboriginal, pre-Columbus peoples, “native American” was a term adopted by the restriction movement to describe purebred Protestants of their own lineage. Much of Brahmin Boston considered what the twenty-first century knows as “native American” rather less positively: Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. called them “a half-filled outline of humanity . . . [a] sketch in red crayons of a rudimental manhood.”

IV. Written during Roosevelt’s tenure as New York City police commissioner, this was one of the many not-quite-suitable-for-public-consumption sentences Lodge excised from the two-volume edition of the Roosevelt–Lodge letters published in 1925.

V. And let these sentences summarize Chamberlain’s view of certain non-Aryans: “And here a fact occurs to me which I have received from various sources, viz., that very small children, especially girls, frequently have quite a marked instinct for race. It frequently happens that children who have no conception of what ‘Jew’ means, or that there is any such thing in the world, begin to cry as soon as a genuine Jew or Jewess comes near them! The learned can frequently not tell a Jew from a non-Jew; the child that scarcely knows how to speak notices the difference. Is not that something?” Chamberlain doesn’t comment on the reaction of tots to approaching Catholics but does point out that the Church of Rome reigns over “chaotic mongreldom.”

VI. Years later Ross dismissed the Leland Stanford family and its storied partners in the Central Pacific—Charles Crocker, Collis Huntington, and Mark Hopkins—as “Sacramento hardware merchants.”

VII. The year before Ross defined “race suicide” in his speech to the political scientists, a small New York publisher issued “A Yellow World,” a pamphlet purporting to consist of a group of letters by the son of a Chinese nobleman, addressed to the Viceroy. Whoever actually wrote it had a somewhat different definition of Ross’s ostensible coinage but an equally vigorous style: “Nothing proves the incapacity and childishly barbaric smallness of the Caucasian brain than the bombastic policy of race suicide pursued by that nation of pudgy braggarts known as Great Britain.”

VIII. It’s true that Adams did have some sneering fun at the Schneidekoupons’ expense: their name, in German, means “coupon clipper.”

IX. The Post editorial was read on the floor of the Senate two weeks later during a debate on another iteration of the literacy test by Furnifold M. Simmons of North Carolina, whose dramatics were as flamboyant as his name. Consider this, from 1928: “I would rather die, I would rather have my right arm cut off, I would rather have my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth, than to vote for” a Catholic for president.

X. A few years earlier, in a magazine article defending the Italians, the generally sympathetic Carr provided earnest, if discouraging, context: “Like all their immigrant predecessors,” he wrote, “Italians profess no special cult of soap and water.” But, he added with what he must have considered reassuring affirmation, “here too are differences, for some Italians are cleaner than others.”

XI. One such was a Calabrian teenager named Angelo Siciliano, who on a field trip to the Brooklyn Museum became entranced by the classical sculptures, particularly the Discus Thrower, the Dying Gladiator, and other imposing physical specimens. The boy asked Davenport if he could develop a similar body. Decades later, Siciliano—by then known as the bodybuilder Charles Atlas—recalled Davenport’s life-altering reply: “If you were willing to work hard enough you could.”