9

New evidence for non-elite burial patterns in central Turkey

Abstract

Little is currently known about non-elite burial practice in central Anatolia. The funerary landscape of Roman Galatia has remained a comparatively elusive one; its population, largely composed of rural subject peoples with a mixed ethnic background, used few permanent markers to memorialize their dead. The key to identifying patterns of burial practice and commemoration among this non-elite populace clearly lies in a study of rural cemeteries, few of which have been investigated. Excavations at Gordion between 1950 and 1995 have provided a promising means to study the character of rural Galatian burial practice, in the form of 147 Roman-period burials belonging to three necropoleis which span from the mid-1st century to the early 5th century AD. Their examination has permitted an initial modelling of local, diachronic patterns of non-urban funerary activity, one that features the use of multiple construction types in a single necropolis, a preference for single interment, alignment along cardinal axes, and a substantial transformation of burial practice in late Antiquity. The publication of data from recent rescue excavations and established projects like Çatalhöyük has now provided an opportunity to test this model independently. Preliminary assessment of this new data appears to strengthen the case for certain widespread patterns of funerary activity within central Turkey which resemble those observed at Gordion. Examination of burial geography in rural Galatia has also revealed a widespread reuse of pre-Roman sites and cemeteries as Roman necropoleis, suggesting that rural non-elites chose to commemorate their own dead through proximity with monuments of Anatolia’s pre-Roman past.

Keywords: cemeteries, Galatia, geography, Gordion, memory, Roman-period.

Introduction

In a paper delivered in 1997 on burial in Roman Asia Minor, M. Spanu candidly lamented the present state of mortuary archaeology in Anatolia. He pointed out that not only had Rome’s Asiatic provinces garnered only cursory mention (when mentioned at all) in scholarly discussions of Roman funerary practice, but he also highlighted the ‘almost total absence of extensive archaeological excavations of cemeteries’ in Turkey, where conditions were ‘only slightly offset by the state of preservation… of funerary monuments and by sporadic, restricted rescue excavations, mostly unpublished or locally published and therefore difficult to find’ (Spanu 2000, 169). Nearly twenty years later, as the studies contained in this volume amply demonstrate, fundamental steps are being taken to remedy this state of research, including the expansion of excavation in Roman-period necropoleis, better recording practices, greater methodological and theoretical deliberation, and wider, more rapid publication of the results (for example, Devreker 2003; Şimşek 2011; Krsmanovic and Anderson 2012; Kelp 2013). Yet in spite of such promising developments, the general foci of fieldwork on Roman burial practice and ritual in Turkey have changed little since Spanu’s much-deserved critique (Krsmanovic and Anderson 2012, 58–60). The preponderance of new fieldwork and scholarship on Roman cemeteries remains concentrated largely in the western and coastal regions of Turkey, as well as centred almost exclusively upon urban or elite burials and their associated monuments. No attempt has yet been made to construct the type of analytical models or even provisional studies like those produced for Imperial Roman provinces such as Britain and Pannonia, with the intent to examine extensive and diachronic variation in burial context and practice (Pearce 2013; Leleković 2012). Likewise, the types of associated issues outlined by J. Pearce (1992), such as burial and cultural identity, funerary ritual and the relationship of burial to the landscape, remained largely unaddressed within the provinces of Roman Anatolia.

This is particularly true for the inland provinces of the Anatolian plateau like Galatia, where little is yet known about Roman-period burial practice and commemoration. In comparison with its neighbouring regions, Galatia’s funerary landscape is admittedly difficult to identify, investigate and characterize, largely lacking as it does the prominent material remains associated with Roman-period burials found elsewhere in Anatolia. This is due in at least part to the general pattern of regional settlement in Galatia, which contained few cities of any size. The vast majority of its population was of a non-elite and non-urban character, living in villages or estates scattered across the rural landscape (Mitchell 1993, 143–9). Once outside the immediate environs of Galatia’s few cities (e.g. Ancyra and Pessinus), evidence for Roman-period necropoleis and associated monuments is relatively scarce, especially when compared to neighbouring funerary landscapes like that of western Phrygia, with its comparably plentiful Asiatic sarcophagi and rock-cut tomb façades (Kelp 2013, 79–86). While funerary sculpture and markers are certainly not absent from Galatia, the prevalent types which have been recorded – statues of crouching lions, Phrygian ‘doorstone’ stelae, tombstones with pediments and acroteria, and plain, inscribed bomoi – tend to be simple in form and found in proximity to urban areas (Temizer 1973, 82–5). This appears to be true even among the region’s elite class, as indicated by the eventual cessation of Galatia’s most elaborate pre-Roman form of funerary construction, the building or reuse of mounded tumuli. This burial tradition, with its origins in north-west Anatolia, remained popular with the region’s Galatian elite through the end of the Hellenistic period, as indicated by the mounded tombs with elaborately constructed stone chambers at Karalar (ancient Blucium) and in Tumulus O at Gordion (Young 1955, 191–7; 1956, 251–2; Arık and Coupry 1935; Mitchell 1993, 57). Such construction and reuse does continue sporadically within or near the borders of Galatia into the early Imperial period: the Kocakızlar Tumulus near the village of Alpu (Midaeum) has been dated to the early or mid-1st century AD on the basis of coins and a sigillata bowl (Atasoy 1974), while two tumuli just to the north of Ankara’s Esenboğa Airport, near the villages of Akkuzulu Köy and Kalecik, date on the basis of ceramic finds (unguentaria) to the second half of the 1st or early 2nd century AD (Anlağan 1968; Mermerci 1988). Yet while there is clear and growing evidence for the construction of later Imperial tumuli in Galatia (Cinemre 2014a, 350), such evidence remains comparative scarce, suggesting strongly that the long-term popularity of this burial type had largely ceased by Roman times even among central Anatolia’s elite (Goldman 2007, 317).

The relative absence of evidence for an overtly lavish tradition of funerary practice and commemoration across the landscape of Roman Galatia is probably owed less to the vagaries of preservation than to the underlying economic and demographic factors that prevailed among the population of this Roman province. As noted previously, Galatia held few urban centres, and the epigraphic record suggests that while agriculturally rich areas such as the Sangarius and Tembris valleys held numerous Imperial and private estates, wealthy landholders preferred to reside in Roman Galatia’s cities or farther abroad (Mitchell 1993, 148–9). The general distribution of wealth and elite residency therefore seems the most likely factor for a clustering of funerary monuments around Galatia’s few cities. The simultaneous scarcity of such monuments elsewhere in Galatia appears likely to be rooted in the character of its rural economy, which was overwhelmingly based upon agricultural and pastoral activities. S. Mitchell (1993, 154–7) has suggested that at the onset of the Imperial period, certain pre-Roman conditions – specifically the existence of a tribal social structure with greater transhumant behaviour – provided ambitious domainal landlords with an opportunity to carve out large rural estates and eventually to introduce the widespread cultivation of cereal agriculture. Mitchell has proposed, as was the case in neighbouring Asia and Bithynia, that local landowners were forced to sell off their holdings in order to meet the rising demands of Roman provincial taxation. Whatever the cause, village life came to predominate under this new system of rural land ownership, one which featured a tenant population who chiefly practiced large-scale dry cereal farming and animal husbandry. This populace, who possessed a far lower standard of living than Galatia’s city dwellers, are likely to have had little capacity for constructing or purchasing funerary monuments, a circumstance that might well account for the scarcity of permanent memorials within the Galatian hinterlands (Mitchell 1993, 253–8).

Consequentially, if we are to ascertain the character of burial practice and its context in the Galatian landscape, we must turn to an investigation of rural cemeteries and their predominantly non-elite burials. Until relatively recently, such an investigation has not been possible owing to a general dearth of fieldwork across Galatia, where archaeological activity on Roman sites has concentrated almost entirely upon its few urban centres (i.e. Pessinus, Ancyra, Tavium). However, new excavations in the Roman cemeteries at Gordion during the 1990s, in combination with a reassessment of funerary contexts and materials unearthed and recorded there during the 1950s and 1960s, have created an initial opportunity to explore rural funerary practice and non-elite burial customs in Galatia. The resulting sample from the three cemeteries, composed of 147 graves dating between the first and fifth centuries AD, has provided the basis for constructing a much-needed diachronic model of local funerary activity in Galatia. Furthermore, the past decade has witnessed an increase in the publication of contemporary necropoleis at a variety of sites in central Anatolia, both the product of rescue excavations and fieldwork at established sites where study of Roman (or ‘late’) material previously languished. The fortuitous arrival of this newly published data, supplemented by online archives of the rescue projects and their finds, has presented the means for comparing local patterns observable at Gordion on a broader, regional scale. Following an overview of the Gordion data, mortuary patterns at four rural sites will be examined as a means to detect what (if any) regional patterns of funerary activity might be identified as widespread within Galatia. This paper will conclude by offering some tentative observations about burial patterns within central Turkey, what amounts to a necessary first step forward in creating a broader understanding of Roman mortuary activity in central Anatolia.

Before proceeding, however, a requisite note of caution must be interjected here, well-trodden territory for anyone familiar with synthetic publications about ancient mortuary patterns in the Roman world. Indeed, it has become de rigueur within articles on the subject of rural burial to preface discussion with a long list of necessary caveats, whose purpose is to concede limitations in the existing data, to address deficiencies in local conditions, and to pinpoint the needle’s eye through which one’s necessarily narrow threads of scholarly inquiry must emerge. This study is no more immune to the confines and vagaries that beset similar analyses of fieldwork elsewhere in Rome’s provinces, with acknowledged impediments in the quality of recording and data of the type that Spanu and others have often cited. In his study of town cemeteries in Roman Britain, for example, S. E. Cleary (1992) provides a daunting list of empirical shortcomings that might well describe fieldwork conditions in Galatia, including an absence of statistically valid samples, cemeteries which have been excavated only in part, the slow adoption of palaeopathological investigation, and more. The data examined in this article suffers from similar weaknesses: publication of funerary data in Turkish periodicals is often only of preliminary character; field methodology and recording varies greatly in quality; valuable contextual information is often missing, as the cemetery and its associated settlement were not excavated in tandem; and so forth.

Likewise, one cannot proceed with a study of burial practice such as that proposed here without acknowledging the significant interpretive and methodological concerns that attend any investigation of burial and cultural identity. For Galatia, the subject of cultural identity is an exceedingly complex one in light of the province’s high level of ethnic diversity. While such diversity is a characteristic of many regions of Anatolia and the Roman world in general, Galatia possessed an unusually heterogeneous mix that is well attested within Imperial epigraphic and literary sources. Among those living under Roman suzerainty in this vast province were people of Phrygian descent, tribal groups such as the Pisidians and Lycaonians to the south, and those descended from immigrants connected with successive waves of invaders, such as the Persians, Hellenistic Greeks, and Galatians of Celtic origin. The latter group was particularly influential following its arrival in the early 3rd century BC, and common speech across Roman Galatia, especially in the countryside, appears to have remained strongly Celtic through late Antiquity. Attested Celtic place names are fairly plentiful in Roman Galatia (e.g. Vindia, Acitorigiaco, Ecobrogis), and within funerary inscriptions family units often display an assortment of Celtic, Phrygian, Roman, and Greek names. Phrygian names in particular continue to be encountered commonly on the central plateau, and ‘neo-Phrygian’ curse formulae appear on tombstones with Greek inscriptions in western Galatia during the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD (Mitchell 1980, 1056–68; 1993, 50–1, 172–6).

As one might imagine, the discernment or isolation of ethnic characteristics from among the non-elite burials of Galatia represents a challenging task, since it has been demonstrated through post-processual critique that mortuary treatment by its very nature is not a direct reflection of a living people’s social or ethnic identity. As J. Pearce (1992, 2–5) asserts, it is hard to achieve differentiation between burial practices of incomers and indigenous peoples in many situations, such as whenever one attempts to assign origin or cultural affiliation to burial practice, to identify local patterning in burial with a conscious ethnic identity or local group, and to distinguish local variation and the rate of persistence of local practice within a community. For the Roman period, one must also consider the relevance of Roman political geography and its partition of administrative units (here Galatia) with the grouping of burial evidence. Additionally, in the specific case of Galatia, any effort to discern changes in burial practice are impeded by a current lack of evidence for the region’s pre-Roman, non-elite burial traditions. Furthermore, the general paucity of Roman-period funerary epitaphs and monuments in Galatia makes the study of migration during that period quite difficult (Pearce 2010, 81–2).

Consequentially, at present we cannot attempt to measure with any accuracy the rate or impact of multi-ethnic accultural practices, including those intrusive funerary forms which might be considered ‘Roman’. Indeed, Imperial Rome is merely one of many non-indigenous, Iron Age cultures that must be considered when investigating the rural mortuary landscape of Galatia. By comparison and necessity, then, the analysis presented in this paper is a narrowly focused one, its objective to facilitate future discussion on themes of burial and cultural identity in Galatia, as a first step towards eventual engagement with and contribution to the broader theoretical and contextual discourse taking place elsewhere in the Roman world. Yet while the goal of this nascent analysis is admittedly a modest one, and while the excavation of non-urban cemeteries remains infrequent in Galatia, enough recent fieldwork has been completed and published to make such an initial inquiry a possible and beneficial exercise.

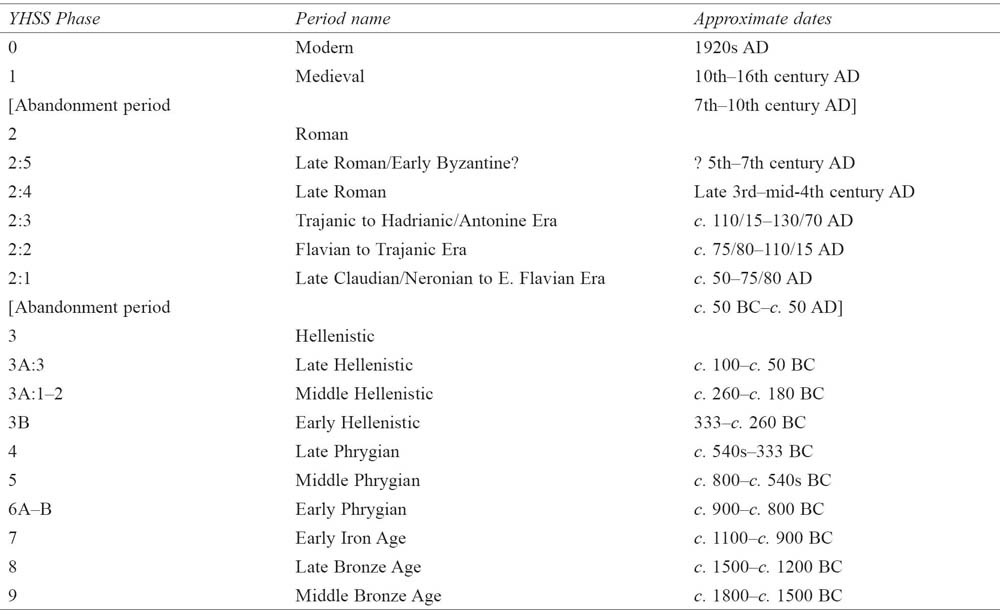

The Roman-period cemeteries at Gordion

Writing at the advent of the Roman Imperial period, Strabo informs us that the former Phrygian capital of Gordion (modern Yassıhöyük) had been reduced to a small village amid a landscape of ruins (Geog. 12.5.2: kômê). Recent fieldwork on the Gordion Citadel Mound has disproved Strabo’s observation: stratified deposits confirm that the site in fact lay abandoned at the time of Galatia’s annexation by Augustus (c. 25 BC), with resettlement taking place only during the late Claudian or early Neronian period, roughly 75 years later (YHSS 2) (Table 9.1). At that time a small auxiliary base was established atop the mound, providing a permanent military presence along the major highway which ran south-west from Ancyra to Colonia Germa and Pessinus (modern Babadat and Ballıhisar, respectively). The small base, never more than 3 ha in area, was occupied for roughly 75 years (YHSS 2:1–3) before its abrupt abandonment in the early Hadrianic period, possibly as a result of Hadrian’s reorganization of the Empire’s military forces (Goldman 2010, 136–8). An auxiliary presence remained based in the area, however, as indicated by a pair of early 3rd-century Roman military altars recovered in 2008 from the Sakarya river. Dedicated by members of the cohors I Augusta Cyrenaica to Caracalla and Geta (the latter’s name erased), these altars have revealed the name of the unit stationed at the site, one known to have operated in Galatia in the 2nd and 3rd centuries (Darbyshire et al. 2009). Although the exact position of this second base in relation to the Sakarya river crossing has not yet been established, the site is most likely to be identified with the statio known in Roman road itineraries as Vindia or Vinda, which was located in the vicinity of Gordion (Goldman 2010, 136). Excavations atop the Citadel Mound indicate that the initial settlement was again occupied by the late 3rd century (YHSS 2:4–5), perhaps in response to Gothic and Palmyrene raids into the heartland of Anatolia. Limited settlement activity, which included the creation of a necropolis amid derelict YHSS 2:4 buildings (the NWZ cemetery; see below), appears to have continued into late Antiquity until a final abandonment, in the 6th or 7th century AD.

Table 9.1. Gordion. The Yassıhöyük Stratigraphie Sequence (YHSS) (M. M. Voigt and A. Goldman).

In addition to producing a chronological framework for Gordion’s Roman occupation, investigation of the YHSS 2 settlement has focused on the excavation and analysis of three contemporary necropoleis located on or around the Citadel Mound (Fig. 9.1): the South Lower Town (SLT) cemetery, containing 31 graves; the Common Cemetery (CC), with 51 graves; and the NW Zone (NWZ) cemetery, with 65 graves. Concentrated fieldwork in the necropoleis began in 1950, when Rodney S. Young and a team from the University of Pennsylvania initiated excavation at Gordion, and continued during the early 1990s under the direction of Mary M. Voigt. Each of the three burial areas associated with this small rural site has been excavated to a limited extent, and two of them – the SLT and CC cemeteries – contain plentiful evidence of both Roman and pre-Roman (YHSS 3–8) mortuary activity. The discovery in 1996 of a funerary stele dedicated to one Tritus, son of Bato, an auxiliary soldier from Pannonia, has raised the possibility that the settlement possessed a fourth cemetery, one which lay north-west of the Citadel Mound along the Roman road which ran north of the present course of the Sakarya river (Goldman 2010). Excavation has not yet been initiated in this area, however, so that its existence must remain hypothetical at present.

The results of the three investigated cemeteries and their contents are summarized below. While osteological and palaeodemographic data is available for the most recently excavated necropolis (i.e. the SLT cemetery), limitations in space precludes their discussion here (see Selinsky 2004; Goldman and Voigt 2016, forthcoming). Instead, the following sections will offer overviews of grave construction techniques, associated burial practice, orientation, demarcation, and range of offering types. In order to facilitate description and comparison between the Gordion necropoleis, a typology of grave construction form has been created (Table 9.2) using categories first defined for the Common Cemetery (in Goldman 2007) and later adapted to reflect practices in the Area A-B sample (in Goldman and Voigt 2016, forthcoming). In some cases the CC types were subdivided (e.g. Type 1 into 1a, 1b and 1c), and two new categories – Type 7: busta, and Type 8: cist graves – were added. While the sample size for the SLT cemetery is small, and the numbers for each variant type are even smaller, splitting (rather than lumping) is intended as a means of facilitating comparison with cemeteries elsewhere.

Fig. 9.1. Gordion. Plan of the site and its cemeteries with Roman road (B. Marsh).

Table 9.2. Gordion. Roman burial construction typology:

Types 1–8 (A. Goldman and M. M. Voigt). |

|

Type 1: Simple pits (3 variants) |

|

1a |

Simple pit, carefully cut in a rectangle or ovular shape |

1b |

Simple pit, with small slabs or small stones placed above body |

1c |

Simple pit, shallow, with small pile of rocks placed on stone slab or directly on body |

Type 2: Stepped graves (2 variants) |

|

2a |

Stepped grave, with simple earth shelves, mudbrick cover |

2b |

Stepped grave, with paved stone shelves |

Type 3: Mud-brick sarcophagi (2 variants |

|

3a |

Mud-brick sarcophagus, roughly rectangular boxes |

3b |

Mud-brick sarcophagus, roughly rectangular boxes, with some stone lining |

Type 4: Wooden coffin in pit or pit with wooden cover |

|

Type 5: Tile and/or brick graves (2 variants) |

|

5a |

Grave constructed of tile and/or brick, used as lining |

5b |

Grave constructed of tile and/or brick, used as cover |

Type 6: Chamber tomb |

|

Type 7: Bustum, with cinerarium for cremated ashes and bones |

|

Type 8: Cist grave, stone-lined with stone covert |

|

The South Lower Town cemetery (1st–2nd century AD = YHSS 2:1–3)

The earliest of Gordion’s three Roman cemeteries was laid out in the South Lower Town (SLT) area between the Citadel Mound and the Küçük Höyük (KH), a multi-storied middle Phrygian fortress and the siege mound built against it by the Persians in the mid-6th century BC (Fig. 9.1). Excavations on the top and slopes of the Küçük Höyük in the late 1950s and in Areas A and B during the mid-1990s exposed architectural remains dating to the middle and late Phrygian periods (YHSS 5 and 4), as well as a series of partial and comingled human and animal skeleton deposits (including complete human skeletons with evidence of trauma) dated to middle Hellenistic periods (YHSS 3A:1–2). The latter have been linked with ritual sacrifice carried out by the Galatian population who took control of Gordion around the mid-3rd century BC (Voigt 2012, 263–84).

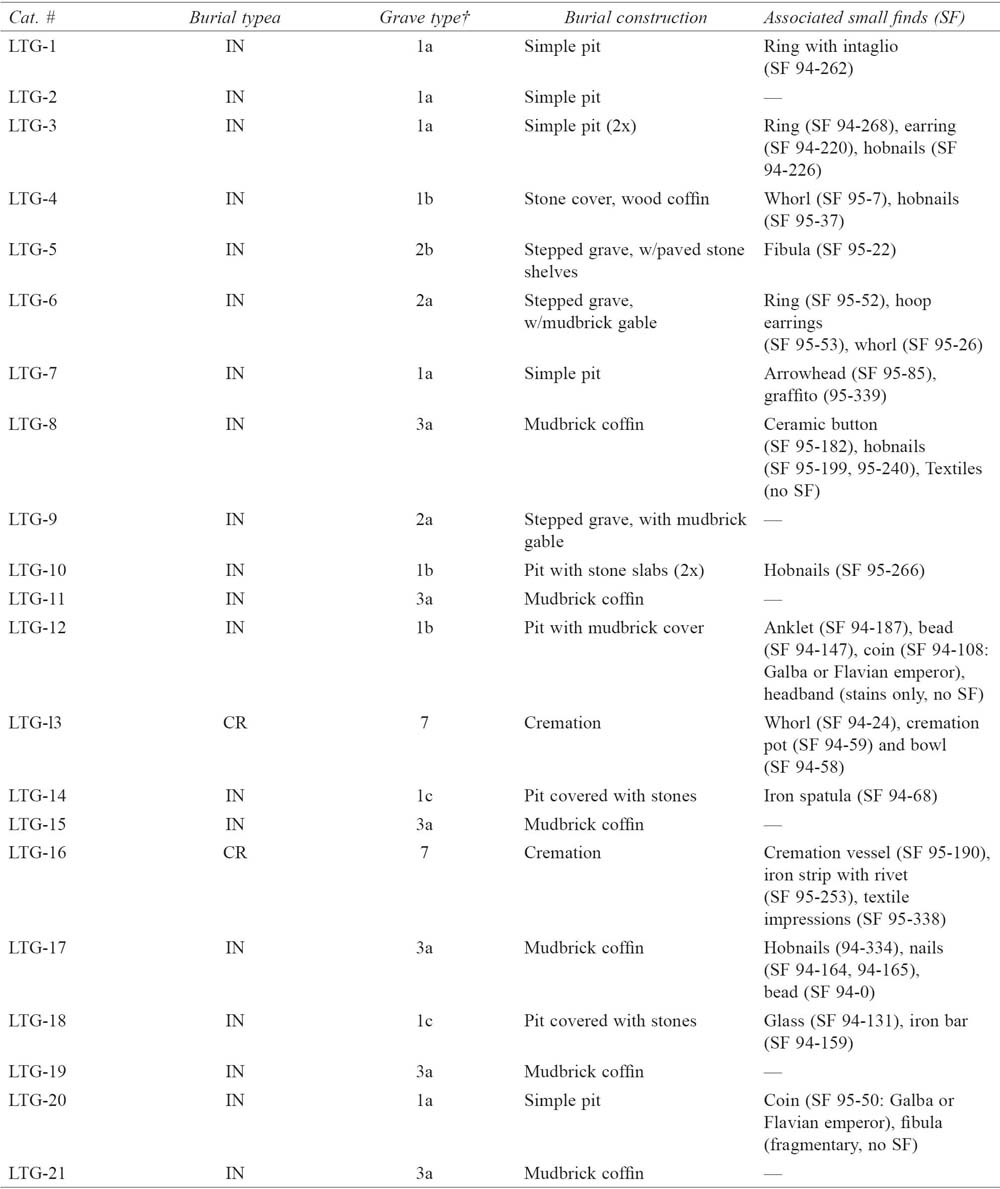

Following the mid-1st century AD resettlement of the Citadel Mound (YHSS 2:1), burial activity in the SLT resumed and Roman burials were inserted alongside and occasionally cut into the pre-Roman deposits. A total of 31 Roman-period burials – 28 inhumations and three cremations, containing a minimum of 34 individuals – have been excavated in the SLT cemetery (Table 9.3). Ten of these were uncovered in Area A (LTG-1 to 10) (Fig. 9.2), 11 in Area B (LTG-11 to 21) (Fig. 9.3), and 10 along the top and slopes of the Küçük Höyük (LTG-22 to 31). An additional five graves were recorded in Areas A and B but could not be excavated owing to time and funding. As the graves from the KH area were casually unearthed and poorly recorded during the 1950s, discussion here will focus on the 21 graves from Areas A and B, those excavated with greater precision in the 1990s. Among this group, there are four categories of grave construction: Type 1 (pit graves), Type 2 (stepped graves), Type 3 (graves with mud-brick lining), and Type 7 (busta). It is in fact unclear whether or not even the 21 burials from SLT Areas A and B belong to one or several bounded necropoleis, since the orientation of grave shafts differs between the areas. However, similarities in grave construction types and in the dates of the funerary assemblage in Areas A and B as well as on the KH fortification walls suggest continuity in time and perhaps in space.

In regard to burial construction, Type 1 or pit graves were most common (10 of 21, or 47.6%). Three sub-types were defined based upon the way that stone was used within the grave pit, and the depth of the pit. In most cases, the shaft of a Type 1 grave was a carefully cut rectangle approximating the size of the body within it, but two graves were clearly oval. Shaft depth was c. 1.0–1.5 m. The deceased (mostly adults) were laid out in an extended dorsal position, with straightened legs, upper arms parallel to the body and lower arms crossed over the abdomen (as in LTG-1) (Fig. 9.4). The four Type 1b pit graves are differentiated from the unembellished Type 1a examples by the addition of stone slabs or smaller stones placed directly above the body, near the bottom of the grave shaft. Likewise, Type 1c consisted of infant graves – LTG-14 and 18 in Area B – where a small pile of rocks was placed upon a stone slab or directly atop the body which lay in a very shallow pit. These stones would have served both as a protective cover for the body and a marker for the grave.

Type 2 graves have a more complex construction: the body lay at the bottom of a deep shaft, placed in a secondary cut made below a narrow ledge or stepped shelf. Although numerous in CC necropolis (see below), the SLT cemetery contained only three stepped graves, all in Area A. The first two (Type 2a) were for children, and have simple earth shelves on which mud bricks were set to cover the body: (LTG-6 (Fig. 9.5), and LTG-9. The adult grave (Type 2b) is unique at Gordion in that the step to either side of the body was partially paved with stone (LTG-5).

Type 3 graves – seven of which were excavated in Areas A and B – consist of pits within which a sarcophagus of mud brick has been constructed around the body. In a majority of the examples, roughly rectangular boxes composed of irregular-sized, greenish mud bricks (L. 0.25–55 m, W. 0.08–25 m) were assembled inside the burial trench (e.g. LTG-21) (Fig. 9.6). In all examples of graves with mud-brick coffins, skeletal position was identical to that found in the shaft graves, with bodies laid out on their backs, legs straight and arms bent over the abdomen. Type 3 burials were found in all of the SLT excavation units, but were more common in Area B. Adults, children and infants were interred in about equal numbers. Such crude mud-brick sarcophagi were likely constructed as a practical measure, as a means of better protecting bodies and their associated burial offerings from rodent disturbance.

Table 9.3. Gordion. SLT cemetery grave and burial types, with associated objects (A. Goldman).

IN = Inhumation; CR = Cremation. † Types 4 (wooden coffins), 5 (infant burials with reused ceramic or brick elements) or 6 (chamber tombs), which are present in the Common Cemetery, are not currently represented in the Southern Lower Town Cemetery.

Fig. 9.2. Gordion. Plan of Area A, in the SLT cemetery (compiled by A. Goldman; digitized by T. Ross).

Fig. 9.3. Gordion. Plan of Area B, in the SLT cemetery (compiled by A. Goldman; digitized by T. Ross).

Fig. 9.4. Gordion. Plan of LTG-1, Type 1 pit grave from Area A, SLT cemetery (S. Jarvis; digitized by T. Ross).

Type 7 burials, which to date have been documented only within the SLT necropolis, are cremation pits or busta. At Gordion these consist of shallow rectangular trenches with rounded corners in which the dead were burnt and their cremated remains subsequently gathered and secondarily interred in associated ceramic containers (cineraria). Two excavated busta from the SLT Area B (LTG-13, 16) and at least one more from the KH trenches have yielded urns and offerings that clearly identify them as Roman and belonging to the inhabitants of the YHSS 2:1–3 settlement. LTG-13, the best preserved of the two busta, is composed of a shallow pit placed on a north-west/south-east orientation, with a length of c. 2.25 m, a width of c. 1.15 m, and a depth of c. 0.5 m (Figs. 9.7–8). Remains of the in situ pyre, which left the roughly parallel sides of the trench fired bright orange in colour, lay in the approximate centre of the bustum. It consisted of an irregular patch of burnt, blackened soil c. 0.60 m in diameter which still containing small fragments of bone. Three patellas were identified in the total sample, suggesting that this is a multiple cremation, with a second individual present in this burial. Most of the cremated remains were gathered together once the pyre had cooled and placed in a common ware pitcher. Some sort of offering appears to have been placed in the cinerary vessel as well, since several of the bones displayed a greenish tinge, indicating contact with a copper alloy object, but no metal fragments were recovered from either the urn or the trough. Completing the burial practice, a small, roundish niche was cut into the north wall of the bustum and the pitcher, capped by a broken echinus bowl, was interred inside it to create a final resting place for the deceased. A small post-sized hole discovered c. 0.20 m to the east of niche seems to indicate that a grave marker of some type was installed there to identify the site of the collected remains (cf. Faber 1998, postholes at Cambodenum in southern Germany). Both the pitcher and the bowl have parallels with ceramics from contexts dating to YHSS 2:1–3 within the Roman settlement, indicating a probable date of the second half of the 1st century or early 2nd century AD (Voigt et al. 1997, 13–4; Sams and Voigt 1996, 437 and fig. 11). Slight variations can be observed between the two busta: the troughf LTG-16 maintains a different orientation (12˚ north-west, in comparison to 55˚ north-west), and its cinerarium was interred in the south-east corner of the trough, in a niche that is encircled by rocks, cordoned off from the area of the funerary pyre. Yet the general ritual and furniture are quite similar, with the body burnt in situ – a ‘hot’ bustum, in contrast to a ‘cold’ bustum in which the ashes and bones were transferred from a nearby pyre (ustrinum) – and use of a wide-mouthed vessel to store the cremated remains in an immediately adjacent location (Matijasic 1991, 85–7).

Fig. 9.5. Gordion. Plan of LTG-6, Type 2 stepped grave from Area A, SLT cemetery (S. Jarvis; digitized by T. Ross).

Fig. 9.6. Plan of LTG-21, Type 3 mud-brick sarcophagus from Area B, SLT cemetery (S. Jarvis; digitized by T. Ross).

Fig. 9.7. Gordion. Photo of LTG-13, Type 7 busta from Area B, SLT cemetery (Gordion Archive).

The placement of small stones, wood, bricks and potsherds above the body is found in all grave types. A distinctive attribute of infant and child burials in the SLT cemetery is the placement of mud bricks or sherds above the body. In the case LTG-21 (Fig. 9.6), a child’s body was placed in a crude mud-brick coffin and a square mud brick was then laid over the chest, while in LTG-6, another child burial was given a gabled mud-brick vault (Fig. 9.5). The latter can be considered an imitation of the ‘tent’ burial popular throughout the Roman Empire. Tent burials were normally constructed using fired roof tiles (tegulae) leaned against each other to form a triangular, tent-like cover (e.g. Pessinus Type B3, in Devreker 2003, 48–9). Unlike similar cappuccina burials in Italy, however, curved cover tiles (imbrices) are generally absent along the top and sides of the Galatian examples. At Gordion, where there is no evidence in the YHSS 2:1–3 settlement for either the manufacture or use of pan or cover tiles, the desire or need to fashion tegula-like structures appears to have driven residents to substitute available building materials (i.e. mud bricks) in order to fashion an acceptable likeness of this fashionable or familiar style.

Evidence for wood covers is also present in the SLT cemetery, in the burial of a child (LTG-17) and an adult (LTG-4). In the former, large iron nails (L. 0.087 m) with rectangular sections were found inside the Type 3 mud-brick coffin, while in the latter a line of nails was found beneath stone slabs, the nails extending down the centre of the long axis of the body. Pseudomorphic evidence in the form of both vertical and horizontal wooden grain patterns preserved along the corroded nail shafts indicate that nailed wooden planks were clearly present in the grave, although it could not be determined whether they originally belonged to a complete coffin, a bier or a wooden cover. One possible interpretation of the line of nails is that that wooden planks were placed immediately above the body, held together by the nails.

Fig. 9.8. Gordion. Plan of LTG-13, Type 7 busta from Area B, SLT cemetery (S. Jarvis; digitized by T. Ross).

While the limited area of investigation and non-contiguous character of the trenches render it difficult to detect any large-scale patterns of interment across the entire SLT cemetery, it is possible via the existing sample of burials and offerings to detect certain more localized characteristics relating to organization (orientation and distribution), content and dating. In SLT Area A (Fig. 9.2), the 11 recorded Roman burials (excavated and non-excavated) display a consciously arranged scheme of deposition, with the majority of burials maintaining a roughly consistent north/south orientation (between 0°İ north and 17°İ north-east), similar equidistant placement (c. 1.25 m apart), and indications of elementary linear alignment (e.g. LTG-4, 7, and 8). Skeletal position within the graves is relatively uniform, with supine extended inhumations, heads normally placed to the north, arms crossed over the lower abdomen. In contrast, the 15 burials of SLT Area B (Fig. 9.3) are not only placed more distantly apart in most cases, but they also lie co-mingled along two opposing axes, with a dominant north-east/south-west group interspersed with a north-west/south-east group along the Area B’s western edge. Notably, the dominant group consists largely of Type 3 inhumations (e.g. LTG-15, 17, 19), while the second, smaller group is the only one to contain cremations (LTG-13, 16). Among the inhumations, while skeletal posture (extended with arms crossed) is identical to that observed in Area A, the positioning of the crania varies greatly, observing no discernable pattern among the excavated sample. Exactly what this intriguing differentiation in alignment, construction type and body orientation might reflect is uncertain. Such variation could potentially be a sign of two distinct, unrelated phases of interment, datable evidence for which is currently lacking. Alternatively, the juxtaposition of a second axis might indicate the importation of ethnic or cultural practices new to the site or region, an effect of the influx of soldiers into Gordion. Although identification of long-distance migration through burial practice remains difficult, as J. Pearce (2010, 93) has recently asserted, the military function of the site does provide a viable context within which such a proposal can be offered.

Although on several occasions the Roman graves in the SLT cut into and disturb the pre-Roman burials, the fact that none in either Area A or B cut into or overlie one another indicates that some system of grave markers was employed throughout the necropolis for the purpose of organization and commemoration. This was certainly the case for two infant burials (LTG-14, 18) in Area B, where small piles of rocks were placed carefully over the body to demarcate the grave. Although difficult to recover, there is also evidence for rough stone markers for adult graves. No evidence for other permanent markers has been identified, however, suggesting that the inhabitants employed markers made of organic materials (i.e. wood) or that the site’s post-Roman inhabitants subsequently scavenged any stone markers, removing all surface trace of the graves. Either case (or both) of such loss would help to explain the high degree of preservation among the graves of the SLT cemetery.

In terms of offerings, funeral gifts are rare in the SLT cemetery, especially for adults (Table 9.3). For example, with the exception of the cremation burials, no ceramic vessels (including lamps) were placed within or associated with the LTG burials, and only two coins were found, both from the early Flavian period. Glass finds are also infrequent at Gordion, although a well-preserved candlestick unguentarium was recovered from an infant’s grave in Area B (LTG-18). J. Jones (personal communication, 2013) dates this find to the 2nd or early 3rd century. When datable, such grave goods belong to the 1st through 3rd centuries AD, indicating that burials began with or shortly after the establishment of the settlement in YHSS 2:1 (c. mid-1st century AD), and apparently continued after the population moved off of the Citadel Mound at the end of YHSS 2:3 during the second or third quarter of the 2nd century.

Items of personal adornment are more common in the SLT cemetery. There is good evidence that the deceased wore clothing at the time of interment, as attested by the calcified remnants of textiles, a button and the hobnails and eyelets of footwear recovered from several of the graves. The remains of such footgear are rarely encountered elsewhere in Roman Anatolia, but relatively frequent at Gordion. Hobnails were recovered from four of the 21 SLT burials, probably the remnants of caligae worn by soldiers and members of their families. These hobnails are even more frequently encountered in the CC burials, in just over one-third of the graves (18 of 51), and should not be understood merely as the accoutrement of soldiers, since they are found in graves of men, women and children at Gordion (Goldman 2007, 313–4; 2014, 182). Other items of personal adornment (e.g. earrings, rings, a headband, an anklet or bracelet, fibulae) were associated with the graves of individuals identified as females by Selinsky (2004). Composed of silver, bronze and iron, most of these objects are quite modest in terms of their craftsmanship and materials, and likely represent everyday items used by the deceased. Such use is reflected, for example, in the worn silver alloy ring with an engraved gemstone found in the grave (LTG-1) of a woman aged 35–40 (Goldman 2014, 165). The ring bore a carved intaglio of yellow-orange carnelian with an image of a winged eros fishing, and around the lower band was a blob of organic adhesive (wax?), applied in order to shrink the band’s width so that it would not slip off the smaller finger of its user. Much of the jewellery represents common types fashionable throughout the Roman Empire, such as the pair of silver earrings from LTG-6, with wire and granulation decoration in the shape of a flower (cf. Ergil 1983, 41 no. 99).

The Common Cemetery (2nd–4th century AD = YHSS 2:3–4)

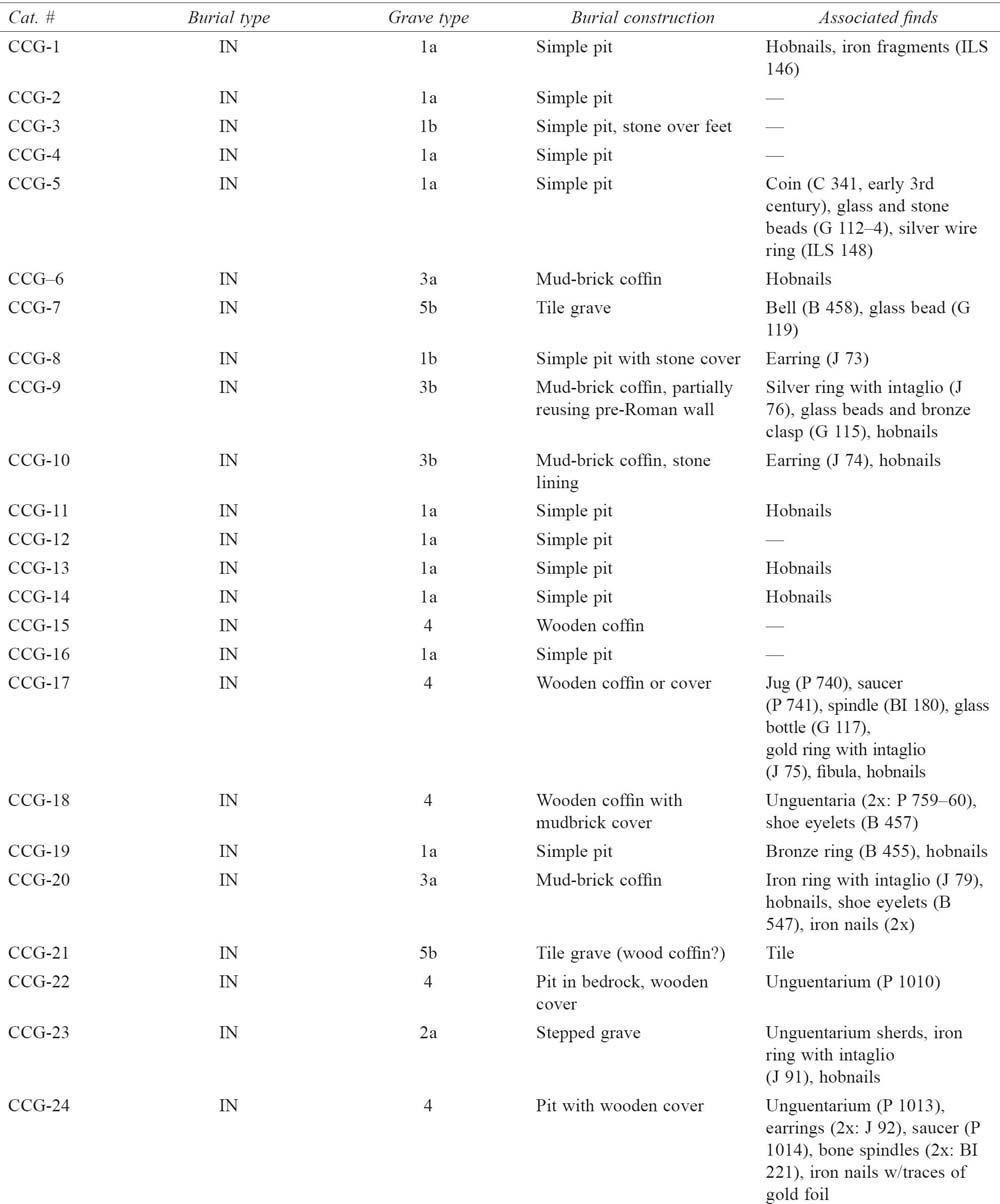

The CC necropolis lies roughly 1 km south-east of the Citadel Mound, along the course of the Ancyra–Pessinus highway (Fig. 9.1). As the road travelled south-west from Ancyra and descended into the Sakarya basin, it neatly bisected a gentle, undulating ridge which forms the lower valley’s eastern edge. Modern Yassıhöyük lies at the ridge’s north-western end, while its spine is crowned by a concentration of over 30 Phrygian tumuli, the exploration of which was another primary target of R. S. Young’s early fieldwork. Sixteen successive trenches laid across that slope between 1951 and 1962 eventually yielded c. 230 graves belonging to a span of over two and a half millennia, from the early Bronze Age through the late Roman period. The majority of the single- and multiple-use interments found there contained few offerings and remain difficult, if not impossible to date. It is this profusion of non-elite burials which led excavators to name the necropolis ‘the Common Cemetery’. At its heart, clustered just north of the highway, 51 Roman-period inhumations dating between the 2nd and 4th centuries AD were unearthed during the course of the fieldwork across an area c. 80 m2. (Fig. 9.9). Since this cemetery has been published in detail elsewhere (Goldman 2007, 305–15) and many of its characteristics are analogous to those of the SLT necropolis, only a brief summary will be offered here.

Strong similarities between the two cemeteries and their contents can be observed among the grave construction types, orientation, spacing, demarcation (or lack thereof) and offering type and frequency. There is a comparable mélange of burial construction types, falling here into six separate categories (Fig. 9.10): pit graves (Type 1: 20 examples), stepped graves (Type 2: 15 examples), graves lined with stone and/or mud brick (Type 3: six examples), wooden coffin burials (Type 4: six examples), graves lined with ceramic tile or brick (Type 5: three examples), and one example of a chamber tomb (Type 6). Although there is some clustering of construction types (e.g. Type 2 in the Museum Site Trench), all of the excavated areas containing Roman burials had a mixed complement. Inhumations predominate here, as they do in the SLT necropolis, and there is a similar positioning of the skeletons, again supine and extended, with arms crossed over the abdomen and crania to the north. While cremation burials do occur in the Common Cemetery, they do not demonstrate the busta form with cineraria (Type 7), and there is no evidence that the rite was still practised there during the Roman period. The most common graves are single or multiple interments of the Type 1 pit category, followed by Type 2 step graves. Type 3 sarcophagi are present as well, three of which (CCG-9, 10, 43) incorporated small stone elements, while a fourth (CCG-20) was capped by an elaborate imitation of a tegula gable made of reused mud brick (Goldman 2007, 310, fig. 7).

Fig. 9.9. Gordion. Map of the Common Cemetery with Roman-period burial area (original by G. Anderson; revised by A. Goldman).

Fig. 9.10. Gordion. Plan of Common Cemetery trenches with Roman burials (A. Goldman).

The three categories of grave construction that are not found in the SLT but are present in small numbers here are Types 4, 5, and 6. The three Type 5 graves (CCG-7, 21, 37) all belong to infants and children, and brick and tile are used in the lining and cover much like the use of stone in Type 1c. Although slightly more numerous, the use of wooden coffins (Type 4) appears to have been relatively infrequent as well, as were the mud-brick sarcophagi (Type 3). Perhaps not surprisingly, these more elaborate and presumably expensive burial types tend to be accompanied by offerings in higher numbers and of a higher quality, often in the form of jewellery and ceramic vessels (see below). In one Type 4 burial, CCG-24, the remnants of gold foil was found on the tops of the coffin nails. Interestingly, many of these coffins were placed more closely to the road, while simple pit burials (Type 1) tend to cluster more thickly further from the highway, a pattern which suggests that proximity to the roadway might have been reserved for those of higher status. Also close to the roadway is the single example of a chamber tomb, CCG-33. The tomb, which was found looted, consists of a rectangular access shaft (1.10×0.90 m) 0.75 m in depth, at the bottom of which, sealed by an upright limestone slab and cut deeply into the hardpan, was a nearly squared burial chamber (1.75×2.0 m) with a ceiling which sloped from the entranceway to the rear of the chamber (Goldman 2007, 308–12, fig. 8). Subterranean chambers with sloped ceilings and deep entrance shafts of this type are common at sites along the northern and eastern littoral of the Black Sea, such as Tanais, Zavetnoe, and Zolotoe, and perhaps we see here an outside influence from those regions (Arseneva 1977, 79–81; Firsov 1999, 3–4; Korpusova 1983, 104–8). Since only a single example of such a tomb has been identified, however, it is difficult to say anything beyond the fact that this type is an apparent rarity at Gordion.

In terms of spacing and orientation, alignment of burial in the Common Cemetery varies between north/north-west and north/north-east with only a single exception, CCG-42, an outlying pit grave oriented south-east/north-west. Orientation is thus fairly uniform here, laid out roughly north/south, with some slight variations, more akin to the orientation of SLT Area A rather than SLT Area B. There is no attempt to align the graves directly with the road, which runs north-east to south-west towards the Citadel Mound, as is sometimes the case in extra-mural cemeteries. Once again we find graves neatly separated from each other, suggesting that markers of some type (organic?) were in place, yet no trace of them remains.

In regard to offerings (Table 9.4), we see both a similar incidence of placement within the graves or on the bodies – nearly 75% of the burials had one object or more, as in the SLT cemetery – and a similar range of commonplace, daily objects with no explicit religious or ceremonial function. While a wider array of ceramic objects was recovered here (e.g. unguentaria, small amphorae, pitchers, cosmetic saucers), their numbers remain quite small and their presence infrequent. Glass vessels were also found in only small quantities, no lamps were recovered, and only a single coin was unearthed, a bronze half-assarion of early Severan date that was pierced and reused in a child’s necklace. As in the SLT cemetery, the most common categories of object were those of personal adornment, including standard jewellery types such as gold, silver, bronze, and iron rings with engraved gemstones, gold and silver earrings, necklaces composed of beads, and a bronze bracelet. Also present in small numbers were personal accessories, such as bronze bells and mirrors, carved bone hair-pins and bone spindles. While a small fraction of the objects do occur in precious metals (gold and silver), few are of outstanding quality or workmanship, and the general impression presented here is one of only moderate to low levels of wealth within this rural settlement (Goldman 2007, 312–4). In addition, this collection of offerings is useful in permitting us to distinguish the general span of burial activity in the CC necropolis, between the 2nd and 4th centuries AD, beginning at the period near or just following the abandonment of the Citadel Mound (YHSS 2:3) and continuing until or just after its reoccupation in YHSS 2:4. Thus while the earliest graves are perhaps contemporary with those from the SLT cemetery, this necropolis as a whole appears to be a largely successive burial ground, in use during the period when the Roman base had moved off of the mound.

The North-West Zone Cemetery (4th–5th century AD = YHSS 2:5)

A third necropolis has been explored at Gordion, a small but crowded late Roman cemetery lying on the north-western edge of the Citadel Mound itself, in the North-West Zone of excavation. Discovered and largely unearthed in 1950 during Young’s preliminary season of excavation, the necropolis (c. 30 x 40 m) is composed of stone cist graves (Gordion Type 8), nearly all maintaining a strict east/west orientation (Fig. 9.11). Excavation in this area in 2004 and associated coin finds has confirmed that this cemetery, which is cut into the streets and structures of the YHSS 2:4 occupation phase, was created shortly after the area’s abandonment in the mid-4th century AD and likely continued in use for two to three generations, until the mid-5th century AD (Sams and Goldman 2006, 45). As this cemetery, like the CC necropolis, has been discussed at length elsewhere (Goldman 2007, 301–5), a brief summary will be offered here.

The 65 graves unearthed to date in the North-West Zone cemetery represent the latest burials at Gordion, contained few gifts, and probably relate to the newly identified late Roman or early Byzantine (YHSS 2:5) occupation phase at Gordion. The graves are located in five separate clusters, which might indicate reserved family or clan areas within the necropolis. In contrast to the earlier cemeteries, grave construction and orientation is remarkably uniform in terms of shape, size and material, with cists lined with and covered by large limestone slabs set directly into the YHSS 2:4 surface. Construction materials were clearly scavenged from earlier and nearby structures, and lids of flat limestone slabs cover each grave (3–5 per adult cist, 1–3 for infants and children). Placement of the body is also consistent, laid in a dorsal posture with head to the west, legs extended, arms at the sides, and lower arms folded across the abdomen (with left arm typically placed over the stomach and right set parallel below it, usually over the pelvic area). The very few offerings found within these graves consisted of adornment objects such as glass bracelets, beads, a dove pendant, several flat-banded finger rings, and a twisted wire bracelet. Fragments of tightly woven, un-dyed wool textiles have been identified in one burial, the remnants of a shroud or the deceased’s clothing. Overall, the necropolis is quite similar to other late Roman or early Byzantine cemeteries in central Anatolia, such as Dorylaion, Yalıncak (near Ankara) and Pessinus (Darga 1993, 484–5; Tezcan 1964, 18; Devreker 2003, 56). Such cemeteries with their comparative uniformity in construction and orientation appear to signify that that a major, widespread transition in burial practices had taken place across the region by late Antiquity, one that perhaps should be credited to the arrival and widespread practice of Christianity.

Table 9.4. Gordion. CC necropolis grave and burial types, with associated objects (A. Goldman).

Fig. 9.11. Gordion. Plan of NW Zone cemetery on the Citadel Mound (E. B. Reed; revised by A. Goldman).

Patterns of burial in the necropoleis at Gordion

Among the 147 burials in the three Roman cemeteries discussed above, it is possible to identify certain distinct patterns of burial construction and funerary practice.

First, in terms of grave orientation, a stark difference can be noted between the earlier cemeteries (SLT, CC) and the latest necropolis (NWZ) at Gordion. Graves of the former adopt a predominantly north/south orientation – with slight shifting in alignment to the north-east and north-west (perhaps due to seasonal factors) – while the latter burials clearly and dramatically shift to an east/west orientation, with heads placed to the west. The proximity of the Roman highway does not appear to have been a factor, since that road runs on a north-east/south-west path through the Common Cemetery (Fig. 9.9). Within the SLT and CC necropoleis, it is worth noting not only that the north/south orientation is prevalent between these non-contiguous burial grounds, but that it was also maintained as an established local practice over the course of several centuries, until late Antiquity and the comprehensive adoption of a more uniform burial practice. As in many ancient cemeteries, one does encounter a minority of graves placed in an atypical fashion (e.g. CCG-42, LTG-21) or isolated geographically from the others, as ‘outliers’ (Morris 1992, 179–80). The pair of busta from SLT Area B appear to fall into these categories, and as such they might represent an importation of a mortuary practice from the Roman West, possibly by the troops brought to garrison the 1st-century auxiliary base. Although practice of cremation in Anatolia represents a poorly understood phenomenon, it is now recognized as widespread in Asia Minor (Ahrens 2014; Spanu 2000, 174) and has been explicitly documented at several sites, including 60 examples unearthed in the ‘Acropolis’ cemetery at Pessinus, where the ritual continued in use from the Hellenistic period until c. 300 AD. However, while a variety of cremation types are represented in that necropolis (e.g. simple deposition pits containing cremated remains, cremation graves lined with mud brick, busta), none appear to match those unearthed at Gordion, with the combination of bustum and intact cinerarium (Devreker 2003, 40–3). As a result, it is suggested here on the basis of variation in shape, contents, and orientation that these busta might represent non-indigenous burial practices and forms, perhaps an import from areas in the Roman West where cremation was widely practised, such as Moesia and south-eastern Pannonia in the Danubian region (Oţa 2007; Leleković 2012). In any case, the cemeteries at Gordion show a high level of internal uniformity in regard to orientation.

Second, if one excludes the late Roman graves of the NWZ cemetery, it appears to be the norm at Gordion to have multiple construction types mixed together in close proximity. While clusters of a single burial type can be identified in a few areas (e.g. brick sarcophagi in SLT Area A, stepped graves in the MS Trench), no single category is exclusively dominant in any section of the SLT and CC cemeteries. One constant among them, however, is the generous spacing between the graves, always placed at least a metre apart, occasionally disturbing pre-Roman but never Roman burials. Some type of marking system must have been employed, but aside from a few small piles of stones, all evidence for grave markers is largely lost. However, since only two Roman stelae (both with Latin inscriptions) have ever been recovered from Gordion or its vicinity, the use of more elaborate stone markers at the site does not appear to have been likely (Roller and Goldman 2002; Goldman 2010). This absence contrasts sharply with the numerous funerary inscriptions recorded at Pessinus, suggesting that that urban phenomenon did not translate to the rural landscape, even at a site of moderate prosperity located along one of the region’s major transportation routes.

Third, in regard to burial practice, inhumation clearly predominates, although the SLT Area B busta indicate that cremation was also practised to a limited extent. Given the absence of cremation in the Common Cemetery, where burials on the whole appear to post-date the early Roman settlement phases, it seems reasonable to conclude that cremation rites at Gordion are contemporaneous with and limited to inhabitants of the 2:1–3 settlement. The decline of cremation in favour of inhumation in the later Imperial period is well documented across the Empire, and the burials at Gordion appears to match pattern (Pearce 2010, 82). Among the inhumations, skeletal position is always extended and supine, with lower arms bent and placed across the stomach or abdomen. Single interment appears to have been the customary practice; examples of multiple burials are rare at Roman Gordion, and with one exception (CCG-33, the chamber tomb), they never exceed more than two individuals per grave. Only six of the graves contain more than one body. In nearly all of such cases we have an older female with an infant or neonate, and in the case of the two examples from the SLT cemetery – a young adult and neonate (LTG-3) and a young adult and infant (LTG-10) – the association between bodies would seem mostly likely to be that of mother and child. Secondary interments and multiple burials thus appear to have been quite rare at Gordion.

Finally, some patterns are observable in terms of burial offerings, placement of which normally occurred alongside the head or feet of the deceased on the body, with objects of personal adornment (e.g. rings, earrings) positioned on the body itself. Offerings tend to be utilitarian objects of relatively low quality, and many of the graves contained either no object or only the remnants of the hobnailed boots. Since relatively few offerings aside from personal jewellery or articles of adornment were recovered from any of the cemeteries, from inside or outside the graves, any prevalent customs or rituals associated with burial practice are not evident from our data. The low level of offerings is not surprising, as the deposition of grave goods across the Empire in general was on the decline by the 3rd century (Pearce 2010, 82). Even so, it is notable that the burial of infants and children was conducted with some care, and nearly all contained an object of some sort, such as a glass unguentarium, perhaps reflecting emotional attachment and feelings of loss on the part of the parent(s) or guardian(s).

In sum, it is possible to detect some general patterns among burial practices at rural Roman Gordion between the 1st and 4th centuries AD: burial objects and furniture are relatively simple and minimal, multiple interments are rare, the combination of multiple grave forms in a single necropolis appears to be common (with the exception of late Roman graves), and the graves are oriented and spaced with some care, although apparently lacking in permanent markers of any kind.

Recent fieldwork on Galatian necropoleis

While the analysis offered above is helpful in identifying local patterns of burial practice at Gordion, it must be recognized that various contextual factors could easily have affected the character of the sample in question, rendering it inappropriate or invalid for identifying and studying rural non-elite burial in the region. Among such factors are the site’s function as a military base, the origin(s) of the local garrison, and the proximity of the highway. Differentiating between soldiers and civilians among the deceased is extremely difficult, since no weapons have been found in association with the graves and the 22 pairs of caligae were recovered from graves of men, women and children, indicating that they were worn across the population. In addition, attempts to trace ethnic identity among auxiliary forces on the basis of funerary finds are equally as problematic, as I. Haynes (2013, 135–42) has recently pointed out. Explicit identification of origo through funerary epitaphs like that of the Pannonian Tritus is quite unusual in Galatia, and the expense of ordering, conveying and erecting such a permanent monument must have been substantial, well beyond the means of the average Galatian townsperson or villager. Sadly, Tritus’ tombstone was not found in situ, so that we cannot determine what type of burial was practised by the heir (Mersua) of this Pannonian soldier of the cohors VII Breucorum, a unit known to have been stationed in Germania Superior, Pannonia, and Moesia Superior prior to its arrival at Gordion, most likely during the later years of Trajan’s Parthian War (Goldman 2010, 138–9). Whether such soldiers represent the agency behind the influx of fashionable ‘Roman’ construction types, such as the tegulae burials (or imitations thereof), remains uncertain and at present unknowable. As noted previously, pre-Roman burials have yet to be studied for Galatia, with the result that isolating the mechanisms by which ‘Roman’ types of burial spread across the rural landscape is presently a challenging, if not impossible task.

Given the site’s military function and the periodic influx of garrison troops (at least during the settlement’s early years), it is thus quite reasonable to ask whether we can even consider the Gordion cemeteries as practical candidates for identifying non-elite burial patterns in central Turkey. A case can be made that the primary unit at Gordion, the cohors I Augusta Cyrenaica, which was stationed in Galatia by the early 2nd century and into the 3rd century, might well have adapted to local funerary customs during their long-term assignment. They were certainly recruiting local Galatians into their ranks; funerary epitaphs from Ankara record men recruited from cities in southern Galatia, Iconium and Savatra (Bennett 2009, 113–17). Clearly the solution to assessing the representative character of Gordion’s Roman burials depends upon engaging a larger body of material, an inquiry that has now become possible owing to a growing body of comparative data produced at sites in central Turkey. The primary focus of mortuary archaeology in the region remains urban necropoleis, like those at Pessinus and now the small city of Juliopolis, where a team from the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara has excavated nearly 450 graves since 2009 (Krsmanovic and Anderson 2012; Arslan et al. 2012; Cinemre 2014b).

However, a series of recently published rescue excavations at a scattering of rural Galatian sites is slowly expanding our dataset, as are site descriptions and inventories of objects now available online at www.envanter.gov.tr, a development which greatly facilitates access to the material and preliminary dating of the finds and their contexts. While the quality of recording continues to be inconsistent, as is often the case with rescue work, it is possible now to assess some of the patterns observed at Gordion and to determine their legitimacy as a possible model on a broader, regional scale. A short summary of excavation background, burial construction types, grave orientation, skeletal position, offerings and topographic placement will be presented below for four recently published cemeteries which lie in or on Galatia’s territorial boundaries: Boyalik necropolis, in the Gölbaşi district of Ankara province, with 32 burials excavated in 2008–9; Bahçeçik necropolis, in the Haymana district of Ankara province, with 16 burials excavated in 2009–10; the necropolis at Dadastana, which just west of the Ankara province (on the border of Bithynia), with 25 burials from 2009; and the Neolithic site of Çatalhöyük, with 79 ‘late’ burials excavated between 2003 and 2008 in the 4040 Area.

Boyalık (Gölbaşi district)

In 2007 and 2008, a team from the Ankara Museum investigated a Roman-period necropolis at the village of Boyalık, in the Gölbaşi district due south of Ankara. Situated upon a small hill (Kartalkaya Tepe) to the immediate north-west of the village, the cemetery was originally brought to light in 2002 during construction work on a water tank and had subsequently suffered from looting. In a series of six contiguous trenches (A-1 to A-6), the excavators unearthed a total of 32 inhumation and cremation burials, 18 (M1-18) in 2007 and the remaining 14 (M19-32) in 2008. While a complete analysis of the cemetery and its funerary finds has yet to appear, two preliminary annual reports were issued which contain a descriptive summary of the burials and objects as well as an assortment of plans and photographs. The contents of those reports (Denizli, Kaya, and Çetin 2008; Çetin and Kaya 2010) are discussed below. In addition, an inventory of the recovered objects, including their measurements and photographs, has now been made available to scholars online. Even so, significant problems remain when attempting to analyze this sample of burials, including its relatively small size, the number of disturbed contexts (c. 20%), the widespread scattering of objects from ancient and modern looting activities, and the removal of all grave markers (many of which were observed in reused contexts in the village). From a broader perspective, we also lack evidence for the cemetery’s associated settlement (now probably below the modern village) as well as an estimate of its original extent.

Despite these contextual problems and the incomplete state of the cemetery’s publication, it is evident from the two preliminary reports that general patterns of burial practice, grave construction and offering types observable in the Boyalık necropolis parallel in many ways those observed within the SLT and CC necropoleis at Gordion. Both cremations and inhumations are present at Boyalık, with evidence for the two practices found in close proximity to each other (as they are in SLT Area B). While cremation represents a larger percentage of the excavated graves (nine of 32, 28%) at Boyalık than at Gordion, inhumation continues to predominate in both samples. Although the preliminary reports only contain scant information about the skeletons themselves, single interments appear to be the rule, as at Gordion. Among the inhumations, one observes a similar mixture of construction types, with a predominance of simple pit graves (= Gordion Type 1) and a seemingly random assortment from other familiar categories mixed in, including a stepped grave (= Gordion Type 2), five mud-brick-lined graves (= Gordion Type 3), and a tile grave (= Gordion Type 5). Notably, several of the cremations proved to be similar in form and function with the bustum (LTG-13) in SLT Area B at Gordion (= Gordion Type 7), with a combination of cineraria placed along the edges of pits with burnt orange sides. This discovery raises the possibility that the cremations in the SLT cemetery, previously posited as a military import to Gordion, might well represent a local (Galatian) rather than a migratory burial practice. Finally, although the sample is small in size, the largely modest burial offerings obtained from the Boyalık cemetery are virtually identical in terms of materials, quality and frequency to the finds from Gordion’s Common Cemetery. These include glass and ceramic unguentaria, bronze rings with carved semi-precious stones, small gold loop earrings, glass and stone beads, and bone spindles and hairpins. Also present are ceramic jugs and small amphora of the type found at Gordion, along with nearly a dozen shallow bowls and dishes. Familiar categories of offerings that are missing at Gordion, specifically coins and lamps, are also absent at Boyalık. On the basis of such offerings, the Boyalık burials seem to be contemporary with the graves of the Common Cemetery and thus burial activity is likely to span from the 1st to 3rd centuries AD.

Yet some important differences between the graves at Boyalık and Gordion are apparent as well. Greater deviation is evident in the shape of the cremation pit, which varies from amorphous (M2) to round (M1) and rectangular (M28). In addition, there are several cremations clustered in a single trench (A6), within which only cineraria – reused urns or pithoi – are present (e.g. M21, M22, M24). In terms of grave orientation at Boyalık, adjacent areas of the cemetery display quite different patterns of orientation. For example, contiguous Trenches A3 and A4 contain mostly inhumations which follow a north/south orientation, with a single outlier (M10) on an east/west axis. Just north of these, however, in adjacent Trench A5, the six inhumations excavated between 2007 and 2008 are oriented either due east/west or north-east/south-west. In addition, many of the graves are placed in close proximity to each other, abutting or even cutting into each other to a minor degree. They display a far less ordered arrangement of interment than one finds at Gordion, resulting in a much more haphazard layout of burial at Boyalık. One might expect greater uniformity, as a brief mention in the 2007 preliminary report notes the presence and reuse of funerary stelae in various contexts in and around the village (Denizli, Kaya, and Çetin 2008, 139). Since these monuments appear in secondary contexts, it is impossible to say whether they originated from this necropolis or another in the vicinity. While no description of these stelae has been published, their mere presence does raise the issue as to whether Galatia’s rural residents did in fact have the resources to purchase and erect permanent monuments, as opposed to the non-permanent or rudimentary markers that appear to have been in use at Gordion.

Bahçecik (Haymana district)

In the Haymana district to the south-east of Gölbaşi, on a high ridge near the small town of Bahçecik (c. 55 km south-west of Gordion), illegal excavations led to a 2009 investigation of a late Roman and early Byzantine extramural cemetery. According to the preliminary report on the rescue project (Arslan, Ateşoğulları, and Şahin 2011), a series of five non-contiguous trenches (A–E) were placed along the crest of the ridge over an area of c. 20×80 m, and a total of 16 burials were uncovered (two of which had been robbed). While the quantity of excavated burials here is much smaller here than at Boyalık, they represent an extremely consistent sample that parallels closely the signature of the cist graves (= Gordion Type 8) found in the North-West Zone Cemetery. As at Gordion, all of the graves were identical in construction – lined with stone blocks on the edges and topped with flat slabs – and placed on a strict east/west axis. Skeletons were placed in an identical posture as well, laid out in a dorsal position, with heads to the west and arms bent and placed across the abdomen. In addition, as at Gordion the graves were found to contain very few offerings, which consisted entirely of jewellery items such as glass beads, bronze pendent earrings and bracelets of glass and bronze. The excavators have tentatively dated the objects to the early Byzantine period (c. 5th–7th century AD), which would make this necropolis roughly contemporary with that of the North-West Zone on the Citadel Mound. Again, we have only a small sample here, but it is one which possesses a profile that provides more evidence for a substantial late Antique transformation in burial practice in the region of Gordion.

Islamalan, ancient Dadastana (Nallıhan district)

The village of Islamalan lies just east of the border between the Bolu and Ankara provinces and along the ancient provincial boundary of Bithynia and Galatia (c. 20 km west of Nallıhan and c. 95 km north-west of Gordion). The site was known in antiquity as Dadastana, a town which was chiefly famous for the visit of the Emperor Jovian in 364 AD and his subsequent death there, either of poisoned mushrooms or carbon monoxide poisoning from noxious charcoal fumes (Ammianus Marcellinus 25.10.12–3). A four-week rescue excavation in 2009 unearthed portions of a Roman and early Byzantine necropolis in a sloped, now forested area near the village. Eight trenches (T. I–VIII) were opened and a total of 25 inhumation burials, most in poor shape, were unearthed. No plan of the necropolis and its trenches were published in the brief preliminary report (Arslan, Ceminre and Erdoğan 2011), so that it is difficult to draw more than general conclusions about patterns of spacing. Published photographs of various trenches, however, do suggest ordered spacing in at least some areas that is not unlike that within the Gordion cemeteries. All of the graves discussed in the report were aligned on an east/west axis, and the skeletons (where preserved) were placed in a uniform posture, laid out in a supine and extended position with the head to the west and arms crossed over the abdomen. The majority of these burials consisted of simple pit graves (= Gordion Type 1), but once again we find a mix of construction types, with several examples of coffin burials (with wood fragments and nails), tegula burials (with actual tiles), and stone-lined cist graves (= Gordion Types 4, 5 and 8). Photographs and descriptions of the burial offerings indicate that the finds are of a similar type and quality as those excavated from the Gordion cemeteries and settlement (e.g. small amphorae, glass bracelets, bronze earrings, red-slipped skyphoi). Again, lamps and coins are not seemingly present, although here we find one class of object not at Gordion, specifically small bronze pendant crosses. Although the excavators offer no specific dates for the cemetery, the ceramics and other offerings suggest that burial activity took place between the 2nd and 6th centuries, with the result that at least a portion of these graves are contemporary with those of the Common Cemetery and North-West Zone cemetery.

Çatalhöyük, near Konya

The largest sample of non-elite burials in central Turkey to reach publication in recent years belongs to the Neolithic site of Çatalhöyük, where over 200 ‘late’ burials have been excavated across the site. Data on the graves from the East and West Mounds has until recently been scattered throughout various publications, at a site where multiple teams are in operation and various outlets for publication have been used. Many of the graves have been discussed upon their discovery within the project’s annual reports, such as those unearthed from the Team Poznan (TP) Area since 2001 (Kwiatkowski 2009, for summary). Formal publication of these ‘late’ burials has proceeded more slowly, although one small group from the BACH Area – six graves excavated in 1997–1998 by the Berkeley Team in the upper layers of Building 3 – were recently published as a larger sample, with a more detailed analysis of the accompanying skeletal remains and grave goods (Cottica, Hager and Boz 2012). The complementary settlement(s) for these graves remains unidentified, but does not appear to have been located on either the East or West Mounds.

While a comprehensive study of the burials from the East and West Mounds has yet to appear, the recent publication by S. Moore and M. Jackson (2014) of 79 graves excavated within the 4040 Area of the East Mound between 2002 and 2008 now allows for a wider discussion of the necropolis, its organization and contents. While this large sample of ‘post-Chalcolithic’ burials is located at some distance from the Galatian heartland and Gordion itself (c. 225 km), nevertheless the site still lies within the former boundaries of Roman Galatia and the sample, from a non-urban settlement, is viable for comparison. As such, Çatalhöyük’s ‘late cemetery’ represents a tremendous resource for investigating rural burial in central Anatolia. Significantly, although such ‘late’ burials are of peripheral interest to the Neolithic experts at the site, they have been meticulously excavated and methodically recorded by the various separate teams working on the East Mound. It is worth noting that while similar ‘late’ burials have been recorded at many Bronze Age and earlier sites in Anatolia (see below), few have been accorded the level of recognition or treatment that they have recently received at Çatalhöyük.

Moore and Jackson (2014, 606–13 and fig. 32.2) have currently grouped the 79 graves into four categories (Groups 1 to 4) on the basis of construction type, spatial location, body position and the presence of offerings. These four categories must be understood as provisional, since excavation of the site’s ‘post-Chalcolithic’ burials has continued since 2008 and a larger sample will eventually become available for analysis. Group 1, clustered in the northern section of the necropolis, is composed of 28 rectilinear-cut graves lined with a variety of materials (wood, mud brick, tile). These graves, aligned in an east/west fashion, are considered the earliest of the burials. Fourteen contained burial offerings, personal effects that are almost identical in form and material to those found in the cemeteries at Gordion. These include ceramics (e.g. a cosmetic saucer, unguentaria), glass vessels (e.g. flasks, candlestick unguentaria), a bronze mirror, earrings of gold and bronze, bone spindles, stone beads, iron shoe hobnails, etc. Like the SLT and CC graves at Gordion, only a handful of graves held more than one or two objects. A single, badly corroded coin has been tentatively dated from the mid- to late 2nd century, while carbon dating from one grave (F. 1553) yielded a similar range, of the 1st century to the 3rd century. The six graves excavated in the BACH Area just to the north, which observe a similar orientation, display similar construction techniques and contain similar offerings, also appear to belong to this group of Roman Imperial burials. In comparison, Group 2 is composed of 33 sub-rectilinear graves clustered to the south that contained no offerings or personal objects but with some of the deceased placed in coffins and shrouds. These graves also observe an east/west alignment, although with some at a slightly more south-east/north-west angle. Like several of the Group 1 burials, several of those in Group 2 incorporated tiles or tile fragments in their construction, including one (F. 1476) which may have been used as a grave marker. These burials have been tentatively assigned to the early Byzantine period, on the basis of a single radiocarbon tested skeleton, dating c. 330–410 AD. Group 3 has an entirely different profile: clustered in the south-western part of the necropolis, these 10 graves – all single inhumations, lying on their right sides to face south, perhaps shrouded – are composed of very narrow cuts, either pit graves or lined with mud brick. On the basis of skeletal positioning, the excavators have suggested that these burials are Islamic, facing south towards Mecca. This group might well be linked to graves located to the south-west, in the TP Area, where radiocarbon dating has indicated burial activity spanning the mid-12th to 17th centuries. The 63 graves of the TP Area recorded by the end of 2014, however, differ somewhat in construction, using a ‘niche grave’ design which features an upper rectangular chamber and a second, lower niche chamber within which the body is placed (Kwiatkowski 2009; Filipowicz, Harabasz and Hordecki 2014). Finally, Moore and Jackson’s Group 4 consists of eight outliers or burials in very poor condition, about which little can be said.