The tongue tip touches the ridge, even at the end of a word.

This chapter discusses the sound of L (not to be confused with that of the American R, which was covered in the last chapter). We’ll approach this sound first by touching on the difficulties it presents to foreign speakers of English, and next by comparing L to the related sounds of T, D, and N. (See also Chapter 13, and for related sounds see Chapters 4 and 16.)

L AND FOREIGN SPEAKERS OF ENGLISH

The English L is usually no problem at the beginning or in the middle of a word. The native language of some people, however, causes them to make their English L much too short. At the end of a word, the L is especially noticeable if it is either missing (Chinese) or too short (Spanish). In addition, most people consider the L as a simple consonant. This can also cause a lot of trouble. Thus, two things are at work here: location of language sounds in the mouth and the complexity of the L sound.

Location of Language in the Mouth

The sounds of many Romance languages are generally located far forward in the mouth. My French teacher told me that if I couldn’t see my lips when I spoke French—it wasn’t French! Spanish is sometimes even called the smiling language. Chinese, on the other hand, is similar to American English in that it is mostly produced far back in the mouth. The principal difference is that English also requires clear use of the tongue’s tip, a large component of the sound of L.

The Compound Sound of L

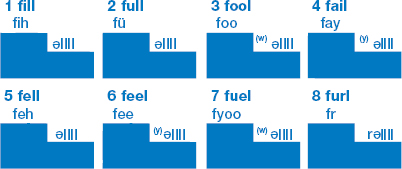

The L is not a simple consonant; it is a compound made up of a vowel and a consonant. Like the æ sound (discussed in Chapter 3), the sound of L is a combination of  and L. The

and L. The  , being a reduced vowel sound, is created in the throat, but the L part requires a clear movement of the tongue. First, the tip must touch behind the teeth. (This part is simple enough.) But then, the back of the tongue must drop down and back for the continuing schwa sound. Especially at the end of a word, Spanish-speaking people tend to leave out the schwa and shorten the L, and Chinese speakers usually leave it off entirely.

, being a reduced vowel sound, is created in the throat, but the L part requires a clear movement of the tongue. First, the tip must touch behind the teeth. (This part is simple enough.) But then, the back of the tongue must drop down and back for the continuing schwa sound. Especially at the end of a word, Spanish-speaking people tend to leave out the schwa and shorten the L, and Chinese speakers usually leave it off entirely.

One way to avoid the pronunciation difficulty of a final L, as in call, is to make a liaison when the next word begins with a vowel. For example, if you want to say I have to call on my friend, let the liaison do your work for you; say I have to kälän my friend.

L Compared with T, D, and N

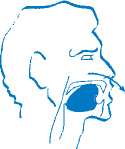

When you learn to pronounce the L correctly, you will feel its similarity with T, D, and N. Actually, the tongue is positioned in the same place in the mouth for all four sounds—behind the teeth. The difference is in how and where the air comes out. (See the drawings in Exercise 6-1.)

T AND D

The sound of both T and D is produced by allowing a puff of air to come out over the tip of the tongue.

N

The sound of N is nasal. The tongue completely blocks all air from leaving through the mouth, allowing it to come out only through the nose. You should be able to feel the edges of your tongue touching your teeth when you say nnn.

L

With L, the tip of the tongue is securely touching the roof of the mouth behind the teeth, but the sides of the tongue are dropped down and tensed. This is where L is different from N. With N, the tongue is relaxed and covers the entire area around the back of the teeth so that no air can come out. With L, the tongue is very tense, and the air comes out around its sides.

At the beginning, it’s helpful to exaggerate the position of the tongue. Look at yourself in the mirror as you stick out the tip of your tongue between your front teeth. With your tongue in this position, say el several times. Then, try saying it with your tongue behind your teeth. This sounds complicated, but it is easier to do than to describe. (You can practice this again later with Exercise 6-3.) Our first exercise, however, must focus on differentiating the sounds.

Exercise 6-1: Sounds Comparing L with T, D, and N |

For this exercise, concentrate on the different ways in which the air comes out of the mouth when producing each sound of L, T, D, and N. Look at the drawings included here to see the correct position of the tongue. Instructions for reading the groups of words listed in Exercise 6-2 are given after the words.

T/D Plosive

A puff of air comes out over the tip of the tongue. The tongue is somewhat tense.

N

Nasal

Air comes out through the nose.

The tongue is completely relaxed.

L

Lateral

Air flows around the sides of the tongue.

The tongue is very tense.

The lips are not rounded!

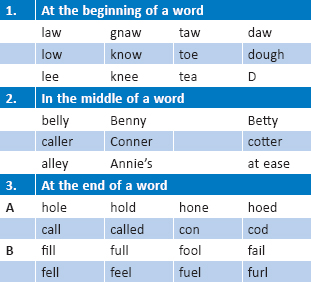

Exercise 6-2: Sounds Comparing L with T, D, and N |

Repeat after me, first down and then across.

Look at group 3, B. This exercise has three functions:

Look at group 3, B. This exercise has three functions:

1.Practice final els.

2.Review vowel sounds.

3.Review the same words with the staircase.

Note Notice that each word has a tiny schwa after the el. This is to encourage your tongue to be in the right position to give your words a “finished” sound. Exaggerate the final el and its otherwise inaudible schwa.

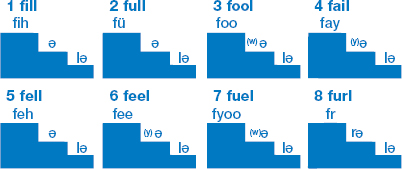

Repeat the last group of words.

Repeat the last group of words.

Once you are comfortable with your tongue in this position, let it just languish there while you continue vocalizing, which is what a native speaker does.

Repeat again: fillll, fullll, foollll, faillll, feellll, fuellll, furllll

Repeat again: fillll, fullll, foollll, faillll, feellll, fuellll, furllll

WHAT ARE ALL THOSE EXTRA SOUNDS I’M HEARING?

I hope that you’re asking a question like this about now. Putting all of those short little words on a staircase will reveal exactly how many extra sounds you have to put in to make it “sound right.” For example, if you were to pronounce fail as fāl, the sound is too abbreviated for the American ear—we need to hear the full fāy l

l .

.

Exercise 6-3: Final El with Schwa |

Repeat after me.

Exercise 6-4: Many Final Els |

This time, simply hold the L sound extra long. Repeat after me.

Exercise 6-5: Liaise the Ls |

As you work with the following exercise, here are two points you should keep in mind. When a word ends with an L sound, either (a) connect it to the next word if you can or (b) add a slight schwa for an exaggerated l sound. For example:

sound. For example:

(a) enjoyable as (b) possible |

enjoy pas |

Note Although (a) is really the way you want to say it, (b) is an interim measure to help you put your tongue in the right place. It would sound strange if you were to always add the slight schwa. Once you can feel where you want your tongue to be, hold it there while you continue to make the L sound. Here are three examples:

Call |

|

|

caw |

kä |

(incorrect) |

call |

cäl |

(understandable) |

call |

källl |

(correct) |

You can do the same thing to stop an N from becoming an NG.

Con |

|

|

cong |

käng |

(incorrect) |

con |

kän |

(understandable) |

con |

kännn |

(correct) |

Find and mark all the L sounds in the familiar paragraph below; the first one is marked for you. There are seventeen of them; five are silent.

Hello, my name is ________. I’m taking American Accent Training. There’s a lot to learn, but I hope to make it as enjoyable as possible. I should pick up on the American intonation pattern pretty easily, although the only way to get it is to practice all of the time. I use the up and down, or peaks and valleys, intonation more than I used to. I’ve been paying attention to pitch, too. It’s like walking down a staircase. I’ve been talking to a lot of Americans lately, and they tell me that I’m easier to understand. Anyway, I could go on and on, but the important thing is to listen well and sound good. Well, what do you think? Do I?

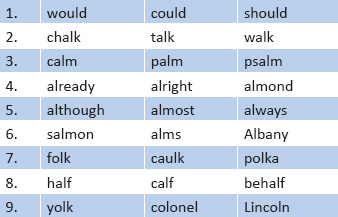

Exercise 6-7: Silent Ls |

Once you’ve found all the L sounds, the good news is that very often you don’t even have to pronounce them. Read the following list of words after me.

Before reading about Little Lola in the next exercise, I’m going to get off the specific subject of L for the moment to talk about learning in general. Frequently, when you have some difficult task to do, you either avoid it or do it with dread. I’d like you to take the opposite point of view. For this exercise, you’re going to completely focus on the thing that’s most difficult: leaving your tongue attached to the top of your mouth. And rather than saying, “Oh, here comes an L, I’d better do something with my tongue,” just leave your tongue attached all through the entire paragraph!

Remember our clenched-teeth reading of What Must the Sun Above Wonder About? (in Chapter 3)? Well, it’s time for us to make weird sounds again.

Exercise 6-8: Hold Your Tongue |

You and I are going to read with our tongues firmly held at the roofs of our mouths. If you want, hold a clean dime there with the tongue’s tip; the dime will let you know when you have dropped your tongue because it will fall out. (Do not use candy; it will hold itself there since wet candy is sticky.) If you prefer, you can read with your tongue between your teeth instead of the standard behind-the-teeth position, and use a small mirror. Remember that with this technique you can actually see your tongue disappear as you hear your L sounds drop off.

It’s going to sound ridiculous, of course, and nobody would ever intentionally sound like this, but no one will hear you practice. You don’t want to sound like this: lllllllllll. Force your tongue to make all the various vowels in spite of its position. Let’s go.

Leave a little for Lola!

Exercise 6-9: Little Lola |

Now that we’ve done this, instead of L being a hard letter to pronounce, it’s the easiest one because the tongue is stuck in that position. Practice the reading on your own, again, with your tongue stuck to the top of your mouth. Read the following paragraph after me with your tongue in the normal position. Use good, strong intonation. Follow my lead as I start dropping h’s here.

Little Lola felt left out in life. She told herself that luck controlled her and she truly believed that only by loyally following an exalted leader could she be delivered from her solitude. Unfortunately, she learned a little late that her life was her own to deal with. When she realized it, she was already eligible for Social Security and she had lent her lifelong earnings to a lowlife in Long Beach. She lay on her linoleum and slid along the floor in anguish. A little later, she leapt up and laughed. She no longer longed for a leader to tell her how to live her life. Little Lola was finally all well.

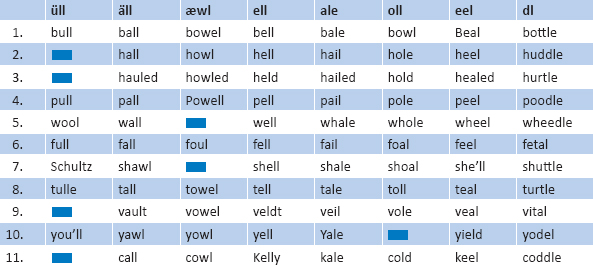

In our next paragraph about Thirty Little Turtles, we deal with another aspect of L, namely consonant clusters. When you have a dl combination, you need to apply what you learned about liaisons and the American T as well as the L.

Since the two sounds are located in a similar position in the mouth, you know that they are going to be connected, right? You also know that all of these middle Ts are going to be pronounced D, and that you’re going to leave the tongue stuck to the top of your mouth. That may leave you wondering: Where is the air to escape? The L sound is what determines that. For the D, you hold the air in, the same as for a final D; then for the L, you release it around the sides of the tongue. Let’s go through the steps before proceeding to our next exercise.

Exercise 6-10: Dull versus –dle |

Repeat after me.

laid |

Don’t pop the final D sound. |

ladle |

Segue gently from the D to the L, with a small schwa in-between. Leave your tongue touching behind the teeth and just drop the sides to let the air pass out. |

lay dull |

Here, your tongue can drop between the D and the L. |

To hear the difference between d l and d

l and d

l, contrast the sentences, Don’t lay dull tiles and Don’t ladle tiles.

l, contrast the sentences, Don’t lay dull tiles and Don’t ladle tiles.

Exercise 6-11: Final L Practice |

Repeat the following lists.

Exercise 6-12: Thirty Little Turtles in a Bottle of Bottled Water |

Repeat the following paragraph, focusing on the consonant + әl combinations. (This paragraph was quoted in The New York Times by Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist, Thomas Friedman.)

Thrdee Lidd l Terd

l Terd l Zin

l Zin Bädd

Bädd l

l Bädd

Bädd l Dwäder

l Dwäder

A bottle of bottled water held 30 little turtles. It didn’t matter that each turtle had to rattle a metal ladle in order to get a little bit of noodles, a total turtle delicacy. The problem was that there were many turtle battles for the less than oodles of noodles. The littlest turtles always lost, because every time they thought about grappling with the haggler turtles, their little turtle minds boggled and they only caught a little bit of noodles.

Exercise 6-13: Speed-reading |

We’ve already practiced strong intonation, so now we’ll just pick up the speed. First, I’m going to read our familiar paragraph as fast as I can. Subsequently, you’ll practice on your own, and then we’ll go over it together, sentence by sentence, to let you practice reading very fast, right after me. By then you will have more or less mastered the idea, so record yourself reading really fast and with very strong intonation. Listen back to see if you sound more fluent. Listen as I read.

Hello, my name is ________. I’m taking American Accent Training. There’s a lot to learn, but I hope to make it as enjoyable as possible. I should pick up on the American intonation pattern pretty easily, although the only way to get it is to practice all of the time. I use the up and down, or peaks and valleys, intonation more than I used to. I’ve been paying attention to pitch, too. It’s like walking down a staircase. I’ve been talking to a lot of Americans lately, and they tell me that I’m easier to understand. Anyway, I could go on and on, but the important thing is to listen well and sound good. Well, what do you think? Do I?

Practice speed-reading on your own five times.

Practice speed-reading on your own five times.

Repeat each sentence after me.

Repeat each sentence after me.

Record yourself speed-reading with strong intonation.

Record yourself speed-reading with strong intonation.

Exercise 6-14: Tandem Reading |

The last reading that I’d like you to do is one along with me. Up to now, I have read first and you have repeated in the pause that followed. Now, however, I would like you to read along at exactly the same time that I read so that we sound like one person reading. Read along with me.