No matter what language you speak, you will have different sounds and rhythms from a native speaker of American English. These Nationality Guides will give you a head start on what to listen for in American English from the perspective of your own native language. In order to specifically identify what you need to work on, this section can be used in conjunction with the diagnostic analysis. The analysis provides an objective rendering of the sounds and rhythms based on how you currently speak, as well as specific guidelines for how to standardize your English; call (800) 457-4255 for a private consultation.

•Intonation

•Liaisons

•Word endings

•Pronunciation

•Location in the mouth

•Particular difficulties

Each section will cover intonation, word connections, word endings, pronunciation, location of the language in the mouth, as well as particular difficulties to work through and solutions to common misperceptions.

Most adult students rely too heavily on spelling. It’s now your job to listen for pure sound and reconcile that to spelling—not the other way around. This is the same path that a native speaker follows.

As you become familiar with the major characteristics and tendencies in American English, you will start using that information in your everyday speech. One of the goals of the diagnostic analysis is to show you what you already know so you can use the information and skills in English as transfer skills, rather than newly learned skills. You will learn more readily, more quickly, and more pleasantly—and you will retain the information and use the accent with less resistance.

Read all the nationality guides—you never know when you’ll pick up something useful for yourself. Although each nationality is addressed individually, there are certain aspects of American English that are difficult for everyone, in this order:

1.Pitch changes and meaning shifts of intonation

2.Regressive vocalization with a final voiced consonant (bit/bid)

3.Liaisons

4.R & L

5.æ, ä, ә (including the æo in ow)

6.Tense & lax vowels (i/ē and ü/ū)

7.Th

8.B, V & W

Nouns generally indicate new information and are stressed.

Ideally, you would have learned intonation before you learned grammar, but since that didn’t happen, you can now incorporate the intonation into the grammar that you already know. When you first start listening for intonation, it sounds completely random. It shifts all around even when you use the same words. So, where should you start? In basic sentences with a noun-verb-noun pattern, the nouns are usually stressed. Why? Because nouns carry the new information. Naturally, contrast can alter this, but noun stress is the default. Listen to native speakers and you will hear that their pitch goes up on the noun most of the time.

You will, however, also hear verbs stressed. When? The verb is stressed when you replace a noun with a pronoun. Because nouns are new information and pronouns are old information—and we don’t stress old information—the intonation shifts over to the verb. Intonation is the most important part of your accent. Focus on this, and everything else will fall into place with it.

Pronouns indicate old information and are unstressed.

Intonation

There are several immediately evident characteristics of a Chinese accent. The most notable is the lack of speech music, or the musical intonation of English. This is a problem because, in the English language, intonation indicates meaning, new information, contrast, or emotion. Another aspect of speech music is phrasing, which tells if it is a statement, a question, a yes/no option, a list of items, or where the speaker is in the sentence (introductory phrase, end of the sentence, etc.). In Chinese, however, a change in tone indicates a different vocabulary word. (See also Chapter 1.)

Important Point

In English, a pitch change indicates the speaker’s intention. In Chinese, a pitch change indicates a different word.

In English, Chinese speakers have a tendency to increase the volume on stressed words but otherwise give equal value to each word. This atonal volume increase will sound aggressive, angry, or abrupt to a native speaker. When this is added to the tendency to lop off the end of each word, and almost no word connections at all, the result ranges from choppy to unintelligible.

In spite of this unpromising beginning, Chinese learners have a tremendous advantage. Here is an amazingly effective technique that radically changes how you sound. Given the highly developed tonal qualities of the Chinese language, you are truly a “pitch master.” In order for you to appreciate your strength in this area, try the four ma tones of Mandarin Chinese. (Cantonese is a little more difficult since it has eight to twelve tones and people aren’t as familiar with the differentiation.) These four tones sound identical to Americans—ma, ma, ma, ma.

The four “ma” tones of Mandarin Chinese

Take the first sentence in Exercise 1-11, It sounds like rain, and replace rain with ma1. Say It sounds like ma1. This will sound strangely flat, so then try It sounds like ma2. This isn’t it either, so go on to It sounds like ma3 and It sounds like ma4. One of the last two will sound pretty good, usually ma3. You may need to come up with a combination of ma3 and ma4, but once you have the idea of what to listen for, it’s really easy. When you have that part clear, put rain back in the sentence, keeping the tone:

It sounds like ma3.

It sounds like rain3.

If it sounds a little short (It sounds like ren), double the sound:

It sounds like

Chinese Intonation Summary

1.Say the four ma’s.

2.Write them out with the appropriate arrows.

3.Replace the stressed word in a sentence with each of the four ma’s.

4.Decide which one sounds best.

5.Put the stressed word back in the sentence, keeping the tone.

When this exercise is successful, go to the second sentence, It sounds like rain, and do the same thing:

It ma3 like rain.

It sounds3 like rain.

Then, contrast the two:

It sounds like rain3.

It sounds3 like rain.

From this point on, you only need to periodically listen for the appropriate ma, substituting it in for words or syllables. You don’t even need to use the rubber band since your tonal sophistication is so high.

Goal

To get you to use your excellent tone control in English.

The main point of this exercise is to get you listening for the tone shifts in English, which are very similar to the tone shifts in Chinese. The main difference is that Americans use them to indicate stress, whereas in Chinese they are fully different words when the tone changes.

A simple way to practice intonation is with the sound that American children use when they make a mistake—uh-oh. This quick note shift is completely typical of the pattern, and once you have mastered this double note, you can go on to more complex patterns. Because Chinese grammar is fairly similar to English grammar, you don’t have to worry too much about word order.

Liaisons

Chinese characters start with consonants and end with either a vowel or a nasalized consonant (n or ng).

All of the advantages that you have from intonation are more than counterbalanced by your lack of word connections. The reason for this is that Chinese characters (words or parts of words) start with consonants and end with either a vowel or a nasalized consonant, n or ng. There is no such thing as a final t, l, or b in Chinese. To use an example we’ve all heard of, Mao Tse Tung. This leads to several difficulties:

•No word endings

•No word connections

•No distinction between final voiced or unvoiced consonants.

It takes time and a great deal of concentration, but the lack of word endings and word connections can be remedied. Rather than force the issue of adding on sounds that will be uncomfortable for you, which will result in overpronunciation, go with your strengths—notice how in speech, but not spelling, Americans end their words with vowel sounds and start them with consonants, just as in Chinese! It’s really a question of rewriting the English script in your head that you read from when you speak. (See also Chapter 2.)

Liaisons or word connections will force the final syllable to be pronounced by pushing it over to the beginning of the next word, where Chinese speakers have no trouble—not even with L.

Goal

To get you to rewrite your English script and to speak with sound units rather than word units.

Written English |

Chinese Accent |

American (with Liaisons) |

Tell him |

teo him |

tellim |

Pull it out |

puw ih aw |

pü li dout |

Because you are now using a natural and comfortable technique, you will sound smooth and fluid when you speak, instead of that forced, exaggerated speech of people who are doing what they consider unnatural. It takes a lot of correction to get this process to sink in, but it’s well worth the effort. Periodically, when you speak, write down the exact sounds that you made, then write it in regular spelling, so you can see the Chinese accent and the effect it has on meaning (puw ih aw has no meaning in English). Then convert the written English to spoken American (pull it out changes to pü li dout) to help yourself rewrite your English script.

When you don’t use liaisons, you also lose the underlying hum that connects sentences together. This coassonance is like the highway and the words are the cars that carry the listener along.

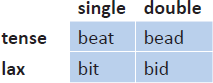

The last point of intonation is that Chinese speakers don’t differentiate between voiced and unvoiced final consonants—cap and cab sound exactly the same. For this, you will need to go back to the staircase. When a final consonant is voiced, the vowel is lengthened, or doubled. When a final consonant is unvoiced, the vowel is short, or single.

Additionally, the long a before an m is generally shortened to a short ε. This is why the words same and name are particularly difficult, usually being pronounced sem and nem. You have to add in the second half of the sound. You need nay + eem to get name. Doubled vowels are explained in chapter 1.

Pronunciation

The most noticeable nonstandard pronunciation is the lack of final L. This can be corrected by either liaisons, or by adding a tiny schwa after it (luh or lә) in order to position your tongue correctly. This is the same solution for n and ng. Like most other nationalities, Chinese learners need to work on th and r, but fortunately, there are no special problems here. The remaining major area is ā, ε, and æ, which sound the same. Mate, met, mat sound like met, met, met. The ε is the natural sound for the Chinese, so working from there, you need to concentrate on Chapters 1 and 3. In the word mate, you are hearing only the first half of the εi combination, so double the vowel with a clear eet sound at the end (even before an unvoiced final consonant). Otherwise, you will keep saying meh-eht or may-eht.

Goal

For you to hear the actual vowel and consonant sounds of English, rather than a Chinese perception of them.

It frequently helps to know exactly how something would look in your own language—and in Chinese, this entails characters. The characters on the left are the sounds needed for a Chinese person to say both the long i as in China and the long ā as in made or same. Read the character, and then put letters in front and in back of it so you are reading half alphabet, half character. An m in front and a d in back of the first character will let you read made. A ch in front and na in back of the second character will produce China. It’s odd, but it works. (See also Chapter 3.)

A word that ends in –ail is particularly difficult for Chinese speakers since it contains both the hard εi combination and a final L (Chapter 1). It usually sounds something like feh-o. You need to say fail as if it had three full syllables—fay-yә-lә. (See also Chapter 6.)

Another difficulty may be u, v, f, and w. The point to remember here is that u and w can both be considered vowels (i.e., they don’t touch anywhere in the mouth), whereas v and f are consonants (your upper teeth touch your lower lip). ū, as in too or use, should be no problem. Similar to ū, but with a little push of slightly rounded lips is w, as in what or white. The letters f and v have basically the same sound, but f is unvoiced and v is voiced. Your lower lip should come up a little to meet your top teeth. You are not biting down on the outside of your lip here; the sound is created using the inside of your lower lip. Leave your mouth in the same position and make the two sounds, both voiced and unvoiced. Practice words such as fairy, very, and wary. (See also Chapter 11.)

There is another small point that may affect people from southern mainland China who use l and n interchangeably. This can be corrected by working with l words and pinching the nose shut. If you are trying to say late and it comes out Nate, hold your nose closed and the air will be forced out through your mouth. (See also Chapter 6.)

æ |

The æ sound doesn’t exist in Chinese, so it usually comes out as ä or ε, so last sounds like lost or name sounds like nem. You need to work on Chapter 3, which drills this distinctively American vowel. (See also Chapters 3, 10, and 12.) |

ä |

Because of spelling, the ä sound can easily be misplaced. The ä sound exists in Chinese, but when you see an o, you might want to say ō, so hot sounds like hōht instead of häht. Remember, most of the time, the letter o is pronounced ah. This will give you a good reference point for whenever you want to say ä instead of ō: astronomy, cäll, läng, prägress, etc. (See also Chapters 3, 10, and 12.) |

o |

Conversely, you may pronounce the letter o as ä or ә when it should be an o, as in only, most, both. Make sure that the American o sounds like ou: ounly, moust, bouth. (See also Chapters 3, 10, and 12.) |

ә |

The schwa is typically overpronounced based on spelling. Work on Chapter 1, “American Intonation,” and Chapter 3, “Cat? Caught? Cut?.” If your intonation peaks are strong and clear enough, then your valleys will be sufficiently reduced as well. Concentrate on smoothing out and reducing the valleys and ignore spelling! (See also Chapters 3, 10, and 12.) |

ü |

The ü sound is generally overpronounced to ooh. Again, spelling is the culprit. Words such as smooth, choose, and too are spelled with two o’s and are pronounced with a long ū sound, but other words such as took and good are spelled with two o’s but are pronounced halfway between ih and uh; tük and güd. (See also Chapters 10 and 12.) |

i |

In most Chinese dictionaries, the distinction between i and ē is not made. The ē is generally indicated by i, which causes problems with final consonants, and the ih sound is overpronounced to eee. Practice these four sounds, remembering that tense vowels indicate that you tense your lips or tongue, while lax vowels mean that your lips and tongue are relaxed and the sound is produced in your throat. Unvoiced final consonants (t, s, k, p, ch, f) mean that the vowel is short and sharp; voiced final consonants (d, z, g, b, j, v) mean that the vowel is doubled. Work on Bit or Beat? Bid or Bead? in Chapter 18. (See also Chapter 12.) |

r |

Chinese speakers usually pronounce American r as ä at the end of a word (car sounds like kaaah) or almost a w in the beginning or middle (grow sounds like gwow). The tongue should be curled back more, and the r produced deep in the throat. (See also Chapter 5.) |

th |

If you pronounce th as t or d (depending if it’s voiced or unvoiced), then you should allow your tongue tip to move about a quarter of an inch forward, so the very tip is just barely between your teeth. Then, from this position you make a sound similar to t or d. (See also Chapter 8.) |

n |

Chinese will frequently interchange final n and ng. The solution is to add a little schwa at the end, just like you do with the el: men |

sh |

Some people pronounce the sh in a particularly Chinese-sounding way. It seems that the tongue is too curled back, which changes the sound. Make sure that the tongue is flat, the tongue tip is just at the ridge behind the top teeth, and that only a thin stream of air is allowed to escape. (See also Chapter 13.) |

t |

American English has a peculiar characteristic in that the t sound is, in many cases, pronounced as a d. (See also Chapter 4.) |

Final Consonants One of the defining characteristics of Chinese speech is that the final consonants are left off (hold sounds like ho). Whenever possible, make a liaison with the following word. For example, hold is difficult to say, so try hold on = hol dän. Pay particular attention to Chapter 2.

Location of the Language

Chinese, like American English, is located in the back of the throat. The major difference between the two languages is that English requires that the speaker use the tongue tip a great deal: l, th, and final t, d, n, l. Chapter 13, “The Ridge,” will help a great deal with this.

Intonation

Although Chinese and Japanese are both Asian languages and share enormously in their written characters, they are opposites in terms of intonation, word-endings, pronunciation, and liaisons. Whereas the Chinese stress every word and can sound aggressive, Japanese speakers give the impression of stressing no words and sounding timid. Both impressions are, of course, frequently entirely at odds with the actual meaning and intention of the words being spoken. Chinese speakers have the advantage of knowing that they have a tonal language, so it is simply a question of transferring this skill to English.

Japanese, on the other hand, almost always insist that the Japanese language “has no intonation.” Thus, Japanese speakers in English tend to have a picket fence intonation: | | | | | | | | | | . In reality, the Japanese language does express all kinds of information and emotion through intonation, but this is such a prevalent myth that you may need to examine your own beliefs on the matter. Most likely, you need to use the rubber band extensively in order to avoid volume increases rather than on changing the pitch. (See also Chapter 1.)

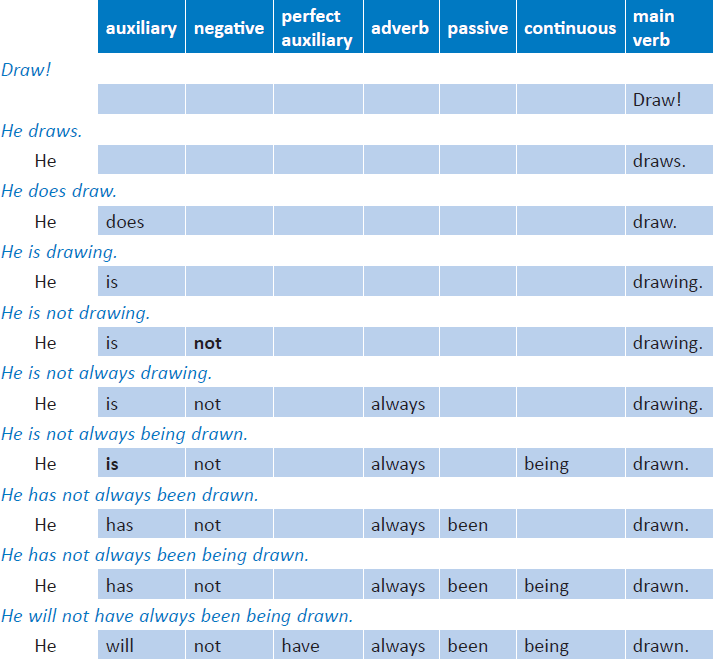

One of the major differences between English and Japanese is that there is a fixed word order in English—a verb grid—whereas in Japanese, you can move any word to the head of a sentence and add a topic particle (wa or ga). Following are increasingly complex verbs with adverbs and helping verbs. Notice that the positions are fixed and do not change with the additional words.

Liaisons

Whereas the Chinese drop word endings, Japanese totally overpronounce them. This is because in the katakana syllabary, there are the five vowels sounds, and then consonant-vowel combinations. In order to be successful with word connections, you need to think only of the final consonant in a word, and connect that to the next word in the sentence. For example, for What time is it? instead of Whato täimu izu ito? connect the two T’s and let the other consonants move over to connect with the vowels: w’täi mi zit? Start with the held t in Chapter 4 and use that concept for the rest of the final consonants. (See also Chapter 2.)

Written English |

The only way to get it is to practice all of the time. |

American accent |

Thee(y)only way dә geddidiz dә præctisällәv th’ time. |

Japanese accent |

Zä ondee weh tsu getto itto izu tsu pudäctees odu obu zä taimu. |

Pronunciation

æ |

The æ doesn’t exist in Japanese; it usually comes out as ä, so last sounds like lost. You need to raise the back of your tongue and drop your jaw to produce this sound. Work on Chapter 3, which drills this distinctively American vowel. (See also Chapters 3, 10, and 12.) |

ä |

The ä sound is misplaced. You have the ä sound, but when you see an o, you want to say o, so hot sounds like hohto instead of haht. Here’s one way to deal with it. Write the word stop in katakana—the four characters for su + to + hold + pu, so when you read it, it sounds like stohppu. Change the second character from to to tä: su + tä + hold + pu, it will sound like stop. This will give you a good reference point for whenever you want to say ä instead of o; impossible, call, long, problem, etc. (See also Chapters 3, 10, and 12.) |

o |

You may pronounce the letter o as ä or ә when it should be an o, as in only, most, both. Make sure that the American o sounds like ou: ounly, moust, bouth. This holds true for the diphthongs as well—oi sounds like ou-ee.

Another way to develop clear strong vowels instead of nonstandard hybrids is to understand the relation between the American English spelling system and the Japanese katakana sounds. For instance, if you’re having trouble with the word hot, say ha, hee, hoo, heh, hoh in Japanese, and then go back to the first one and convert it from ha to hot by adding the held t (Chapter 4). Say hot in Japanese, atsui, then add an h for hatsui and then drop the -sui part, which will leave hot. (See also Chapters 3, 10, and 12.) |

ә |

The schwa is typically overpronounced, based on spelling. Concentrate on smoothing out and reducing the valleys and ignore spelling! (See also Chapters 3, 10, and 12.) |

ü |

Distinguishing tense and lax vowels is difficult, and you’ll have to forget spelling for ū and ü. They both can be spelled with oo or ou, but the lax vowel ü should sound much closer to i or uh. If you say book with a tense vowel, it’ll sound like booque. It should be much closer to bick or buck. (See also Chapters 10 and 12.) |

i |

Similarly, you need to distinguish between e and i, as in beat and bit. Also, tone down the middle i in multisyllabic words; otherwise, similar sim’lr will sound like see-mee-lär. Most likely, you overpronounce the lax vowel i to eee, so that sit is mispronounced as seat. Reduce the lax i almost to a schwa; sit should sound like s’t. In most Japanese dictionaries, the distinction between i and ē is not made. Practice the four sounds—bit, beat, bid, bead—remembering that tense vowels indicate that you tense your lips or tongue, while lax vowels mean that your lips and tongue are relaxed and the sound is produced in your throat. Unvoiced final consonants (t, s, k, p, ch, f) mean that the vowel is short and sharp; voiced final consonants (d, z, g, b, j, v) mean that the vowel is doubled. Work on Bit or Beat? Bid or Bead? in Chapter 10. (See also Chapter 12.) |

The Japanese R = The American T

The Japanese r is a consonant. This means that it touches at some point in the mouth. Japanese speakers usually trill their r’s (tapping the ridge behind the top teeth), which makes it sound like a d to the American ear. The tongue should be curled back, and the r produced deep in the throat—not touching the top of the mouth. The Japanese pronunciation of r is usually just an ä at the end of a word (car sounds like caaah) or a flap in the beginning or middle (area sounds like eddy-ah).

L |

Japanese speakers often confuse the el with r or d, or drop the schwa, leaving the sound incomplete. (See also Chapter 6.) |

th |

The th sound is mispronounced s or z, depending if it is voiced or unvoiced. (See also Chapter 8.) |

v |

v is mispronounced either as a simple bee, or if you have been working on it, it may be a combination such as buwee. You need to differentiate between the four sounds of p/b/f/v. The plosives b/p pop out; the sibilants f/v slide out. b/v are voiced; f/p are unvoiced. b/v are the least related pair. The root of the problem is that you need a good, strong f first. To the American ear, the way the Japanese say Mount Fuji sounds like Mount Hooji. Push your bottom lip up with your finger so that it is outside your top teeth and make a sharp popping sound. (See also Chapter 11.) Practice these sounds: |

Once you have the f in place, simply allow your vocal cords to vibrate and you will then have a v.

|

whispered |

spoken |

popped |

P |

B |

hissed |

F |

V |

w |

The w is erroneously dropped before ü, so would is shortened to ood. Since you can say wa, wi, wo with no problem, use that as a starting point; go from waaaaa, weeeeeeee, woooooo to wüüüüü. It’s more a concept problem than a physical one. (See also Chapter 11.) |

n |

Japanese will frequently interchange final n and ng. Adding the little schwa at the end will clear this up by making the tongue position obvious, as in Chapter 6. (See also Chapter 17.) |

z |

z at the beginning of a word sounds like dz. (zoo sounds like dzoo). For some reason, this is a tough one. In the syllabary, you read ta, chi, tsu, teh, toh for unvoiced and da, ji, dzu, de, do for voiced. Try going from unvoiced sssssue to zzzzzzzoo, and don’t pop that d in at the last second. (See also Chapter 9.) |

si |

The si combination is mispronounced as shi, so six comes out as shicks, and I don’t even want to say what city sounds like! Again, this is a syllabary problem. You read the s row as sa, shi, su, seh, soh. You just need to realize that since you already know how to make a hissing s sound, you are capable of making it before the i sound. (See also Chapter 10.) |

Location of the Language

Japanese is more forward in the mouth than American English and there is much less lip movement.

Intonation

Spanish-speaking people (bearing in mind that there are 22 Spanish-speaking countries) tend to have strong intonation, but it’s usually toward the end of a phrase or sentence. It is very clear sometimes in Spanish that a person is taking an entire phrase pattern and imposing it on the English words. This can create a subtle shift in meaning, one that the speaker is completely unaware of. For example,

Spanish |

English with a Spanish Pattern |

Standard English Pattern |

Quiero comer álgo. |

I want to eat sόmething. |

I want to éat something. |

This is a normal stress pattern in Spanish, but it indicates in English that either you are willing to settle for less than usual or you are contrasting it with the possibility of nothing.

Spanish has five pure vowels sounds—ah, ee, ooh, eh, oh—and Spanish speakers consider it a point of pride that words are clearly pronounced the way they are written. The lack of the concept of schwa or other reduced vowels may make you overpronounce heavily in English. You’ll notice that I said the concept of schwa—I think that every language has a schwa, whether it officially recognizes it or not. The schwa is just a neutral vowel sound in an unstressed word, and at some point in quick speech in any language, vowels are going to be neutralized. (See also Chapter 1.)

Liaisons

In Spanish, there are strong liaisons—el hombre sounds like eh lombre—but you’ll probably need to rewrite a couple of sentences in order to get away from word-by-word pronunciation. Because consonant clusters in Spanish start with an epsilon sound (español for Spanish, estudiante for student), this habit carries over into English. Rewriting expressions to accommodate the difference will help enormously. (See also Chapter 2.)

With Epsilon |

Rewritten |

With Epsilon |

Rewritten |

I estudy |

ice tudy |

excellent espeech |

excellence peech |

in espanish |

ince panish |

my especialty |

mice pecialty |

their eschool |

theirss cool |

her espelling |

herss pelling |

Word Endings

In Spanish, words end in a vowel (o or a), or the consonants n, s, r, l, d. Some people switch n and ng (I käng hear you) for either I can hear you or / can’t hear you. Another consequence is that final consonants can get dropped in English, as in short (shor) or friend (fren). (See also Chapters 4 and 16.)

Pronunciation

With most Spanish speakers, the s is almost always unvoiced, r is trilled, l is too short and lacks a schwa, d sounds like a voiced th, and b and v are interchangeable. Spanish speakers also substitute the ä sound whenever the letter a appears, most often for œ, ä, and ә. Bear in mind that there are six different pronunciations for the letter a as in Chapter 3. Knowing these simple facts will help you isolate and work through your difficulties. (See also Chapter 1.)

The Spanish S = The American S, But . . .

In Spanish, an s always sounds like an s. (In some countries, it may be slightly voiced before a voiced consonant such as in mismo.) In English, a final –s sounds like z when it follows a voiced consonant or a vowel (raise raz, runs rәnz). The most common verbs in English end in the z sound—is, was, does, has, etc. Double the preceding vowel and allow your vocal cords to vibrate. (See also Chapter 9.)

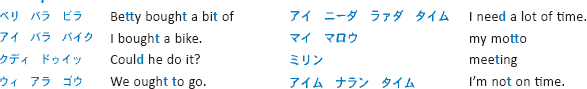

The Spanish R = The American T

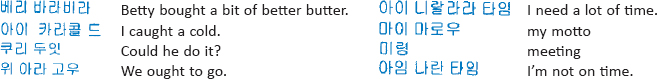

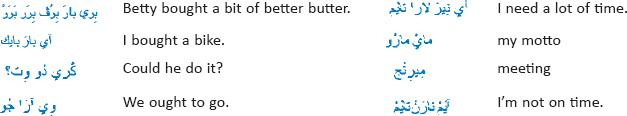

Beri bara bira |

Betty bought a bit of |

ai nira lara taim |

I need a lot of time. |

¡Ai Caracól! |

I caught a cold. |

mai marou |

my motto |

Curi du it? |

Could he do it? |

mirin |

meeting |

ui ara gou |

We ought to go. |

aim naran taim |

I’m not on time. |

In Spanish, r is a consonant. This means that it touches at some point in the mouth. Spanish speakers usually roll their r’s (touching the ridge behind the top teeth), which makes it sound like a d to the American ear. The tongue should be curled back, and the r produced deep in the throat—not touching the top of the mouth. The Spanish pronunciation of r is usually the written vowel and a flap r at the end of a word (feeler is pronounced like feelehd) or a flap in the beginning or middle (throw sounds like tdoh). In English, the pronunciation of r doesn’t change if it’s spelled r or rr. (See also Chapter 5.)

The -ed Ending

You may have found yourself wondering how to pronounce asked or hoped; if you came up with as-ked or hoped, you made a logical and common mistake. There are three ways to pronounce the -ed ending in English, depending what the previous letter is. If it’s voiced, -ed sounds like d: played pleid. If it’s unvoiced, -ed sounds like t: laughed læft. If the word ends in t or d, -ed sounds like әd: patted pædәd. (See also Chapter 4.)

The Final T

The t at the end of a word should not be heavily aspirated. Let your tongue go to the t position, and then just stop. It should sound like hät, not hä, or häch, or häts. (See also Chapter 4.)

The Spanish D = The American Th (voiced)

The Spanish d in the middle and final positions is a fricative d (cada and sed). If you are having trouble with the English th, substitute in a Spanish d. First, contrast cara and cada in Spanish, and then note the similarities between cara and caught a, and cada and father. (See also Chapters 1 and 8.)

cada |

father |

beid |

bathe |

The Spanish of Spain Z or C = The American Th (unvoiced)

The letters z and c in most Spanish-speaking countries sound like s in English (not in Andalusia, however). The z and c from Spain, on the other hand, are equivalent to the American unvoiced th. When you want to say both in English, say bouz with an accent from Spain. (See also Chapters 1 and 8.)

bouz |

both |

gracias |

grathias |

uiz |

with |

The Spanish I = The American Y (not J)

In most Spanish-speaking countries, the y and ll sounds are equivalent to the American y, as in yes or in liaisons such as the(y)other one. Jes, I jelled at jou jesterday can be heard in some countries such as Argentina for Yes, I yelled at you yesterday.

hielo |

yellow (not jello) |

ies |

yes |

iu |

you |

The Doubled Spanish A Sound = The American O, AL, or AW Spelling

Because of spelling, the ä sound can easily be misplaced. The ä sound exists in Spanish, but it is represented with the letter a. When you see the letter o, you pronounce it o, so hot sounds like hoht instead of haht. Remember, most of the time, the letter o is pronounced ah. You can take a sound that already exists in Spanish, such as jaat (whether it means anything or not) and say it with your native accent—jaat with a Spanish accent more or less equals hot in English. This will give you a good reference point for ä instead of o: astronomy, call, long, progress, etc. Focus on Chapter 3, differentiating æ, ä, ә.

jaat |

hot |

caal |

call |

saa |

saw |

The Spanish O = The American OU

You may pronounce the letter o as ä or ә when it really should be an o, as in only, most, both. Make sure that the American o sounds like ou, ounly, moust, bouth. This holds true for the diphthongs as well—oi sounds like ou-ee.

ounli |

only |

joup |

hope |

nout |

note |

æ |

The æ sound doesn’t exist in Spanish, so it usually comes out as ä, so last sounds like lost. You need to work on Chapter 3, which drills this distinctively American vowel. (See also Chapters 10 and 12.) |

ә |

The schwa is typically overpronounced, based on spelling. Work on Chapter 1, “The American Sound” and Chapter 3, “Cat? Caught? Cut?.” If your intonation peaks are strong and clear enough, then your valleys will be sufficiently reduced as well. Concentrate on smoothing out and reducing the valleys and ignore spelling! (See also Chapters 10 and 12.) |

ü |

The ü sound is generally overpronounced to ooh. Again, spelling is the culprit. Words such as smooth, choose, and too are spelled with two o’s and are pronounced with a long ū sound, but other words, such as took and good, are spelled with two o’s but are pronounced halfway between ih and uh; tük and güd. (See also Chapters 10 and 12.) |

i |

Spanish speakers overpronounce the lax vowel i to eee, so sit comes out as seat. In most Spanish dictionaries, the distinction between i and ē is not made. Practice the four sounds—bit, beat, bid, bead—remembering that tense vowels indicate that you tense your lips or tongue, while lax vowels mean that your lips and tongue are relaxed and the sound is produced in your throat. Unvoiced final consonants (t, s, k, p, ch, f) mean that the vowel is short and sharp; voiced final consonants (d, z, g, b, j, v) mean that the vowel is doubled. Work on Bit or Beat? Bid or Bead? in Chapter 10. Reduce the soft i to a schwa; sit should sound like s’t. (See also Chapter 12.) |

|

single |

double |

tense |

beat |

bead |

lax |

bit |

bid |

|

Also, watch out for cognates such as similar, pronounced see-mee-lär in Spanish, and si•m’•lr in American English. Many of them appear in the Middle “I” List. |

l |

The Spanish l lacks a schwa, leaving the sound short and incomplete to the American ear. Contrast similar words in the two languages and notice the differences. (See also Chapter 6.) |

|

|

|

|

v |

A Spanish speaker usually pronounces v and b the same (I have trouble with my bowels instead of I have trouble with my vowels). You need to differentiate between the four sounds of p/b/f/v. The plosives b/p pop out; the sibilants f/v slide out. b/v are voiced; f/p are unvoiced, b/v are the least related pair. Push your bottom lip up with your finger so that it is outside your top teeth and make a sharp popping sound. (See also Chapter 11.) Practice these sounds:

|

Once you have the f in place, simply allow your vocal cords to vibrate and you will then have a v.

|

whispered |

spoken |

popped |

P |

B |

hissed |

F |

V |

n |

The final n is often mispronounced ng—meng rather than men. Put a tiny schwa at the end to finish off the n, menә or thingә, as explained in Chapter 6. (See also Chapter 17.) |

w |

The w sound in Spanish can sound like a gw (I gwould do it). You need to practice g in the throat, rounding your lips for w. You can also substitute in a Spanish ū, as in will uil. (See also Chapter 11.) |

h |

The Spanish h is silent, as in hombre, but Spanish speakers often use a stronger fricative than Americans would. The American h is equivalent to the Spanish j, but the air coming out shouldn’t pass through a constricted throat—it’s like you’re steaming a mirror—hat, he, his, her, whole, hen, etc. In some Spanish-speaking countries, the j is fricative and in others it is not. Also, there are many words in which the h is completely silent, as in hour, honest, herb, as well as in liaisons with object pronouns such as her and him (tell her sounds like teller). (See also Chapter 17.) |

ch |

In order to make the ch sound different from the sh, put a t in front of the Ch. Practice the difference between wash wäsh / watch watch, or sharp sharp / charm chärm. (See also Chapter 13.) |

p |

The American p is more strongly plosive than its Spanish counterpart. Put your hand in front of your mouth—you should feel a strong burst of air. Practice with Peter picked a peck of pickled peppers. (See also Chapter 11.) |

j |

In order to make a clear j sound, put a d in front of the j. Practice George djordj. (See also Chapter 13.) |

sh |

There was a woman from Spain who used to say, “Es imposible que se le quite el acento a uno,” pronouncing it, “Esh imposhible que se le quite el athento a uno.” In her particular accent, s sounded like sh, which would transfer quite well to standard American English. What it also means is that many people claim it is impossible to change the accent, but, as we all know, that is not the case. |

Location of the Language

Spanish is very far forward with much stronger use of the lips.

Intonation

Of the many and varied Indian dialects (Hindi, Telugu, Punjabi, etc.), there is a common intonation transfer to English—sort of a curly, rolling cadence that flows along with little relation to meaning. It is difficult to get the average Indian learner to change pitch. Not that people are unwilling to try or difficult to deal with; on the contrary, in my experience of working with people from India, I find them incredibly pleasant and agreeable. This is part of the problem, however. People agree in concept, in principle, in theory, in every aspect of the matter, yet when they say the sentence, the pitch remains unchanged.

I think that what happens is that, in standard American English, we raise the pitch on the beat, while Indians drop their pitch on the beat. Also, the typical Indian voice is much higher pitched than Americans are accustomed to hearing. In particular, you should work on the voice quality exercise in Chapter 1.

Of the three options (volume, length, pitch), you can raise the volume easily, but it doesn’t sound very good. Since volume is truly the least desirable and the most offensive to the listener, and since pitch has to be worked on over time, lengthening the stressed word is a good stopgap measure. Repeating the letter of a stressed word will help a lot toward changing a rolling odabah odabah odabah intonation to something resembling peaks and valleys.

The oooonly way to geeeeeeedidiz to prœœœœœœœœœktis all of the time.

One thing that works for pitch is to work on the little sound that children make when they make a mistake: “uh-oh!” The first sound is on a distinctly higher level than the second one. Because it’s a nonsense syllable, it’s easier to work with as you’re focusing on pure pitch change and not a real word.

Since so much emotion is conveyed through intonation, it’s vital to work with the various tone shifts in Chapter 1.

It’s necessary to focus on placing the intonation on the correct words (nouns, compound nouns, descriptive phases, etc.), as well as contrasting, negating, listing, questioning, and exclaiming.

Intonation is also important in numbers, which are typically difficult for Indian speakers. There are both intonation and pronunciation differences between 13 and 30. The number 13 should sound like thr-teen, while 30 sounds like thr-dee; 14 is for-teen, and 40 is for-dee. (See also Chapter 1.)

Liaisons

Liaisons shouldn’t be much of a problem for you once the pattern is pointed out and reinforced. (See also Chapter 2.)

Pronunciation

One way to have an accent is to leave out sounds that should be there, but the other way is to put in sounds that don’t exist in that language. Indians bring a rich variety of voiced consonants to English that contribute to the heavy, rolling effect.

t |

For the initial t alone, there are eight varieties, ranging from plosive to almost swallowed. In American English, t at the top of a staircase is a sharp t, and t in the middle is a soft d. Indians tend to reverse this, using the popping British t in the middle position (water) and a t-like sound in the beginning. (I need two sounds like I need doo.) The solution is to substitute your th—it will sound almost perfect (I need thoo sounds just like I need two). Another way is to separate the t from the rest of the word and whisper it. T + aim = time. Bit by bit, you can bring the whispered, sharply popped t closer to the body of the word. A third way is to imagine that it is actually ts, so you are saying tsäim, which will come out sounding like time. (See also Chapter 4.)

The final t is typically too plosive and should be held just at the position before the air is expelled. |

p |

This is similar to the initial t, in that you probably voice the unvoiced p so it sounds like a b. Start with the m, progress to the b, and finally whisper the p sound. (See also Chapter 11.)

|

æ |

The æ sound usually sounds like ä. You might refer to the last class, but it will sound like the lost closs. You should raise the back of your tongue and make a noise similar to that of a lamb. (See also Chapters 3, 10, and 12.) |

ä |

Because of spelling, the ä sound can easily be misplaced. The ä sound exists in the Indian languages, but is represented with the letter a. When you see the letter o, you pronounce it o, so John sounds like Joan instead of Jahn. Remember, most of the time, the letter o is pronounced ah. You can take a sound that already exists in your language, such as tak (whether it means anything or not) and say it with your native accent—tak with an Indian accent more or less equals talk in English. This will give you a good reference point for whenever you want to say ä instead of o; astronomy, call, long, progress, etc. Focus on Chapter 3, differentiating œ, ä, ә. (See also Chapters 3, 10, and 12.) haathotcaalcallsaasaw |

o |

You may pronounce the letter o as ä or ә when it really should be an ö, as in only, most, both. Make sure that the American o sounds like ou, ounly, moust, bouth. This holds true for the diphthongs as well—oi should sould like ou-ee. (See also Chapters 3, 10, and 12.) ounlionlyhouphopenoutnote |

r |

Indians tend to have a British r, which means that it is either a flap at the beginning or middle of a word or it is reduced to ä at the end of a word. You need to understand that the American r is not a consonant (i.e., it doesn’t touch at any two points in the mouth)—it is much closer to a vowel in that the tongue curls back to shape the air flow. (See also Chapter 5.) |

th |

The American th, both voiced and unvoiced, usually sounds like a d when said by an Indian speaker; thank you sounds like dank you. Also you must distinguish between a voiced and an unvoiced th. The voiced ones are the extremely common, everyday sounds—the, this, that, these, those, them, they, there, then; unvoiced are less common words—thing, third, Thursday, thank, thought. (See also Chapter 8.) |

|

Indians usually reverse v/w: These were reversed > Dese ver rewersed. It should be a simple thing to simply reverse them back, but for some reason, it’s more problematic than that. Try substituting in the other word in actual sentences. (See also Chapter 11.) He vent to the store.He closed the went. I’ll be back in a vile.It was a while attack. |

v |

Think of the w, a “double u,” or even as a “single u”; so in place of the w in want, you’d pronounce it oo-änt. There can be NO contact between the teeth and the lips for w, as this will turn it into a consonant. Feel the f/v consonants, and then put oo in place of the w (oo-ile for while). Conversely, you can substitute ferry for very so that it won’t come out as wary. Because of the proximity of the consonants, f and v are frequently interchanged in English (belief/believe, wolf/wolves). Consequently, It was ferry difficult is easier to understand than It was wary difficult. Practice Exercise 11-1 to distinguish among p/b, f/v, and w.

|

L |

The L is too heavy, too drawn out, and is missing the schwa component. (See also Chapter 6.) |

Location of the Language

Far forward and uttered through rounded lips.

Intonation

Russian intonation seems to start at a midpoint and then cascade down. The consequence is that it sounds very downbeat. You definitely need to add a lilt to your speech—more peaks, as there’re already plenty of valleys. To the Russian ear, English can have a harsh, almost metallic sound due to the perception of nasal vibrations in some vowels. This gives a clarity to American speech that allows it to be heard over a distance. When Russian speakers try to imitate that “loudness” and clarity, without the American speech music, instead of the intended pronunciation, it can sound aggressive. On the other hand, when Russians do not try to speak “loud and clear,” it can end up sounding vaguely depressed. (See also Chapter 1.)

Liaisons

Word connections should be easy since you have the same fluid word/sound boundaries as in American English. The phrase dosvedänyә sounds like dos vedanya, whereas you know it as do svedanya. It won’t be difficult to run your words together once you realize it’s the same process in English. (See also Chapter 2.)

Pronunciation

Although you have ten vowels in Russian, there are quite a few other vowels out there waiting for you.

æ |

The æ sound doesn’t exist in Russian, so last is demoted to the lax ε, lest. In the same way, Russian speakers reduce actually to ekchually, or matter to metter. Drop your jaw and raise the back of your tongue to make a noise like a goat: æ! Work on Chapter 3, which drills this distinctively American vowel. (See also Chapters 10 and 12.) |

ä |

The ä sound exists in Russian, but is represented with the letter a. Bear in mind that there are six different pronunciations of the letter a. Because of spelling, the ä sound can easily be misplaced. When you see the letter o, you pronounce it o, so job sounds like jobe instead of jääb. Remember, most of the time, the letter o is pronounced ah. Take a sound that already exists in Russian, such as baab (whether it means anything or not) and say it with your native accent; baab with a Russian accent more or less equals Bob in English. This will give you a good reference point for whenever you want to say ä instead of o: biology, call, long, problem, etc. Focus on Chapter 8, differentiating œ, ä, ә. (See also Chapters 10 and 12.) |

o |

Conversely, you may pronounce the letter o as ä or ә when it really should be an ō, as in only, most, both (which are exceptions to the spelling rules). Make sure that the American o sounds like ou, ounly, moust, bouth. This holds true for the diphthongs as well—oi should sound like ou-ee. (See also Chapters 3, 10, and 12.)

|

ә |

The schwa is often overpronounced to ä, which is why you might sound a little like Count Dracula when he says, I vänt to säck your bläd instead of I wänt to sәk your blәd. Don’t drop your jaw for the neutral schwa sound; it’s like the final syllable of spasiba sp’sibә, not sp’sibä. Similarly, in English, the schwa in an unstressed syllable is completely neutral; famous is not fay-moos, but rather fay-m’s. (See also Chapters 3, 10, and 12.) |

ü |

Distinguishing tense and lax vowels is difficult, and you’ll have to forget spelling for u and ü. They both can be spelled with oo or ou, but the lax vowel ü should sound much closer to i or uh. If you say book and could with a tense vowel, it’ll sound like booque and cooled. It should be much closer to bick or buck. (See also Chapters 10 and 12.) |

i |

Similarly, you need to distinguish between ee and ih, as in beat and bit (Chapter 12), as his big sister is mispronounced as heez beeg seester or with the extra y, hyiz byig systr. Frequently, Russian speakers transpose these two sounds, so while the lax vowel in his big sister is overpronounced to heez beeg seester, the tense vowel in She sees Lisa, is relaxed to shi siz lissa. Also, tone down the middle i in the multisyllabic words; otherwise, similar sim’lr will sound like see-mee-lär. (See also Chapter 10.) |

-y |

Russian speakers often mispronounce the final -y as a short -i, so that very funny sounds like verә funnә. Extend the final sound out with three e’s: vereee funneee. (See also Chapter 12.) |

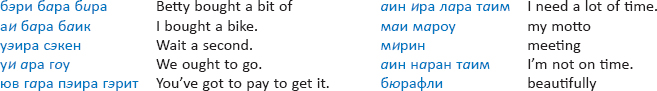

The Russian R = The American T

The Cyrillic r is a consonant. This means that it touches at some point in the mouth. Russian speakers usually roll their r’s (touching the ridge behind the top teeth), which makes it sound like a d to the American ear. The American r is not really a consonant anymore—the tongue should be curled back, and the r produced deep in the throat—not touching the top of the mouth. The Russian pronunciation of r is usually the written vowel and a flap r at the end of a word (feeler sounds like feelehd) or a flap in the beginning or middle (throw sounds like tdoh). (See also Chapter 4.)

|

Another major point with the American r is that sometimes the preceding vowel is pronounced, and sometimes it isn’t. When you say wire, there’s a clear vowel plus the r—wy•r; however, with first, there is simply no preceding vowel. Iťs frst, not feerst (Exercises 5-2 and 5-3). |

t |

At the beginning of a word, the American t needs to be more plosive—you should feel that you are “spitting air.” At the end of the word, it is held back and not aspirated (See also Chapter 4.) |

eh |

One of the most noticeable characteristics of a Russian accent is the little y that is slipped in with the eh sound. This makes a sentence such as Kevin has held a cat sound like Kyevin hyes hyeld a kyet. This is because you are using the back of the tongue to “push” the vowel sound out of the throat. In English, you need to just allow the air to pop through directly after the consonant, between the back of the tongue and the soft palate: k•æ, not k•yæ. (See also Chapters 10 and 12.) |

h |

Another strong characteristic of Russian speech is a heavily fricative h. Rather than closing the back of the throat, let the air flow unimpeded between the soft palate and the back of your tongue. Be sure to keep your tongue flat so you don’t push out the little y mentioned above. Often, you can simply drop the h to avoid the whole problem. For I have to, instead of I hhyef to, change it to I y’v to. (See also Chapter 17.) |

V |

The v is often left unvoiced, so the common word of sounds like oaf. Allow your vocal cords to vibrate. (See also Chapter 11.) |

sh |

There are two sh sounds in Russian, ш and щ. The second one is closer to the American sh, as in щиуз for shoes, not шуз. (See also Chapter 13.) |

th |

You may find yourself replacing the voiced and unvoiced th sounds with t/d or s/z, saying dä ting or zä sing instead of the thing. This means that your tongue tip is about a half inch too far back on the alveolar ridge (the bumps behind the teeth). Press your tongue against the back of the teeth and try to say dat. Because of the tongue position, it will sound like that. (See also Chapter 8.) |

-ing |

Often the -ing ending is not pronounced as a single ng sound, but rather as n and g, or just n. There are three nasals, m (lips), n (tongue tip and alveolar ridge), and ng (soft palate and the back of the tongue). It is not a hard consonant like g, but rather a soft nasal. (See also Chapter 16.) |

Intonation

The French are, shall we say, a linguistically proud people. More than working on accent or pronunciation, you need to “believe” first. There is an inordinate amount of psychological resistance here, but the good thing is that, in my experience, you are very outspoken about it. Unlike the Japanese, who will just keep quiet, or Indians, who agree with everything with sometimes no discernible change in their speech patterns, my French students have quite clearly pointed out how difficult, ridiculous, and unnatural American English is. If the American pattern is a stairstep, the Gallic pattern is a fillip at the end of each phrase. (See also Chapter 1.)

Hello, my name is Pierre. I live in Paris. Allo, my name is Pierre. I live in Paree. I ride the subway.

Liaisons

The French either invented liaisons or raised them to an art form. You may not realize, though, that the rules that bind your phrases together also do so in English. Just remember, in French, it is spelled ce qu’ils disent, but you’ve heard it pronounced colloquially a thousand times, skidiz! (See also Chapter 2.)

Pronunciation

th |

In French, the th is usually mispronounced s or f, as in sree or free for three. (See also Chapters 1 and 8.) |

r |

The French r is in the same location as the American one, but it is more like a consonant. For the French r, the back of the tongue rasps against the soft palate, but for the American r, the throat balloons out, like a bullfrog. (See also Chapter 5.) |

æ |

The æ sound doesn’t exist in French, so it usually comes out as ä or ε; consequently, class sounds like class, and cat sounds like ket. The in- prefix, however, sounds like a nasalized æ. Say in in French and then denasalize it to æd. Work on Chapter 3, which drills this distinctively American vowel. (See also Chapters 3, 10, and 12.) |

ә |

The schwa is typically overpronounced, based on spelling. Work on Chapter 1 for the rhythm patterns that form this sound and Chapter 3 for its actual pronunciation. If your intonation peaks are strong and clear enough, then your valleys will be sufficiently reduced as well. Concentrate on smoothing out and reducing the valleys and ignore spelling! (See also Chapters 10 and 12.) |

ü |

The ü sound is generally overpronounced to ooh, which leads to could being mispronounced as cooled. Again, spelling is the culprit. Words such as smooth, choose, and too are spelled with two o’s and are pronounced with a long ū sound, but other words such as look and took are spelled with two o’s but are pronounced halfway between ih and uh; lük and tük. Leuc and queuc with a French accent are very close. (See also Chapters 10 and 12.) |

|

French speakers overpronounce the lax vowel i to eee, so sit comes out like seat. Reduce the soft i to a schwa; sit should sound like s’t. In most French dictionaries, the distinction between i and ē is not made. Practice the four sounds—bit, beat, bid, bead—remembering that tense vowels indicate that you tense your lips or tongue, while lax vowels mean that your lips and tongue are relaxed, and the sound is produced in your throat. Unvoiced final consonants (t, s, k, p, ch, f) mean that the vowel is short and sharp; voiced final consonants (d, z, g, b, j, v) mean that the vowel is doubled. Work on Bit or Beat? Bid or Bead? in Chapter 10.

Also, watch out for cognates such as typique/typical, pronounced tee•peek in French and tí•p’•kl in American English. Many of them appear in the Middle “I” List in Chapter 10. (See also Chapter 12.) |

ä |

Because of spelling, the ä sound can easily be misplaced. The ä sound exists in French, but is represented with the letter a. When you see the letter o, you pronounce it o, so lot sounds like loht instead of laht. Remember, most of the time the letter o is pronounced ah. You can take a sound that already exists in French, such as laat (whether it means anything or not) and say it with your native accent—laat with a French accent more or less equals lot in English. This will give you a good reference point for whenever you want to say ä instead of o; astronomy, call, long, progress, etc. Focus on Chapter 3, differentiating æ, ä, ә. (See also Chapters 10 and 12.)

|

o |

On the other hand, you may pronounce the letter o as ä or ә when it really should be an o, as in only, most, both. Make sure that the American o sounds like ou, ounly, moust, bouth. This holds true for the diphthongs as well—oi sounds like o-u-ee. (See also Chapters 3, 10, and 12.)

|

h |

French people have the most fascinating floating h. Part of the confusion comes from the hache aspiré, which is totally different from the American aitch. Allow a small breath of air to escape with each aitch. (See also Chapter 17.) |

in– |

The nasal combinations in– and –en are often pronounced like œñ and äñ, so interesting intr’ sting sounds like æñteresting, and enjoy εnjoy and attention әtεnshәn sound like äñjoy and ätäñseeõn. (See also Chapters 1, 10, and 12.) |

Location in the Mouth

Very far forward, with extensive use of the lips.

Intonation

Germans have what Americans consider a stiff, rather choppy accent. The great similarity between the two languages lies in the two-word phrases, where a hόt dog is food and a hot dόg is an overheated chihuahua. In German, a thimble is called a fingerhut, literally a finger hat, and a red hat would be a rote hut, with the same intonation and meaning shift as in English. (See also Chapter 1.)

Liaisons

German word connections are also quite similar to American ones. Consider how In einem Augenblick actually is pronounced ineine maugenblick. The same rules apply in both languages. (See also Chapter 2.)

Pronunciation

j |

A salient characteristic of German is the unvoicing of j, so you might say I am Cherman instead of I am German. Work with the other voiced pairs (p/b, s/z, k/g) and then go on to ch/j while working with J words such as just, Jeff, German, enjoy, age, etc. (See also Chapter 13.) |

w |

Another difference is the transposing of v and w. When you say Volkswagen, it most likely comes out Folksvagen. It works to rewrite the word as Wolksvagen, which then will come out as we say: Volkswagen. A German student was saying that she was a wisiting scholar, which didn’t make much sense—say wisiding with a German accent—it’ll sound like visiting in American English. (See also Chapter 11.) |

th |

In German, the th is usually pronounced t or d. (See also Chapters 4 and 8.) |

r |

The German r is in the same location as the American one, but it is more like a consonant. For the German r, the back of the tongue rasps against the soft palate, but for the American r, the throat balloons out, like a bullfrog. (See also Chapter 5.) |

æ |

The æ sound doesn’t exist in German, so it usually comes out as ä or ε, so class sounds like class. You need to work on Chapter 12, which drills this distinctively American vowel. (See also Chapters 3, 10, and 12.) |

ә |

The schwa is typically overpronounced, based on spelling. Work on Chapter 1 for the rhythm patterns that form this sound, and for its actual pronunciation. If your intonation peaks are strong and clear enough, then your valleys will be sufficiently reduced as well. Concentrate on smoothing out and reducing the valleys and ignore spelling! (See also Chapters 3, 10, and 12.) |

ü |

The ü sound is generally overpronounced to ooh, which leads to could being mispronounced as cooled. Again, spelling is the culprit. Words such as smooth, choose, and too are spelled with two o’s and are pronounced with a long u sound, but other words such as look and took are spelled with two o’s but are pronounced halfway between ih and uh: lük and tük. (See also Chapters 10 and 12.) |

i |

German speakers overpronounce the lax vowel i to eee, so sit comes out like seat. Reduce the soft i to a schwa; sit should sound like s’t. In most German dictionaries, the distinction between i and ē is not made. Practice the four sounds—bit, beat, bid, bead—remembering that tense vowels indicate that you tense your lips or tongue, while lax vowels mean that your lips and tongue are relaxed, and the sound is produced in your throat. Unvoiced final consonants (t, s, k, p, ch, f) mean that the vowel is short and sharp; voiced final consonants (d, z, g, b, j, v) mean that the vowel is doubled. Work on Bit or Beat? Bid or Bead? in Chapter 10.

Also, watch out for words such as chemical/Chemikalie, pronounced ke•mi•kä•lee•eh in German and kεmәkәl in American English. Many of them appear in the Middle “I” List in Chapter 10. |

ä |

Because of spelling, the ä sound can easily be misplaced. The ä sound exists in German, but is represented with the letter a. When you see the letter o, you pronounce it o, so lot sounds like loht instead of laht. Remember, most of the time, the letter o is pronounced ah. You can take a sound that already exists in German, such as laat (whether it means anything or not) and say it with your native accent—laat with a German accent more or less equals lot in American English. This will give you a good reference point for whenever you want to say ä instead of o; astronomy, call, long, progress, etc. Focus on Chapter 12, differentiating æ, ä, ә. (See also Chapters 12, 18, and 20.) haathotcoalcallsaasaw |

o |

German speakers tend to use the British o, which sounds like εo rather than the American ou. Make sure that the American o, in only, most, both, sounds like ou: ounly, moust, bouth. This holds true for the diphthongs as well—oi sounds like o-u-ee. (See also Chapters 12, 18, and 20.) ounlionlylounloannoutnote |

Intonation

While English is a stress-timed language, Korean is a syllable-timed language. Korean is more similar to Japanese than Chinese in that the pitch range of Korean is also narrow, almost flat, and not rhythmical. Many Korean speakers tend to stress the wrong word or syllable, which changes the meaning in English (They’ll sell fish and They’re selfish.) Korean speakers tend to add a vowel to the final consonant after a long vowel: b/v (babe/beibu and wave/weibu), k/g (make/meiku and pig/pigu), and d (made/meidu.) Koreans also insert a vowel after sh/ch/j (wash/washy, church/churchy, bridge/brijy), and into consonant clusters (bread/bureadu). It is also a common problem to devoice final voiced consonants, so that dog can be mispronounced as either dogu or dock. All this adversely influences the rhythm patterns of spoken English. The different regional intonation patterns for Korean interrogatives also affect how questions come across in English. In standard Korean, the intonation goes up for both yes/no questions and wh questions (who?, what?, where?, when?, why?); in the Kyungsang dialect, it drops for both; and in the Julia dialect, it drops and goes up for both. In American English, the intonation goes up for yes/no and drops down for wh questions. (See also Chapter 4.)

Word Connections

Unlike Japanese or Chinese, word connections are common in Korean. The seven final consonants (m, n, ng, l, p, t, k) slide over when the following word begins with a vowel. Although a t between two vowels in American English should be voiced (latter/ladder sound the same), a frequent mistake Korean speakers make is to also voice k or p between two vowels, so back up, check up, and weekend are mispronounced as bagup, chegup, and weegend; and cap is sounds like cab is. Another liaison problem occurs with a plosive consonant (p/b, t/d, k/g) just before a nasal (m, n, ng)—Koreans often nasalize the final consonant, so that pick me up and pop music sound like ping me up and pom music. (See also Chapter 11.)

Pronunciation

l/r |

At the beginning of a word or in a consonant cluster, l and r are confused, with both being pronounced like the American d, which can be written with the letter t (glass or grass sound like either gurasu or gudasu, and light or right sound like raitu or daitu). The final r is usually dropped (car/kaa). (See also Chapters 15 and 16.) |

f |

The English f does not exist in Korean, so people tend to substitute a p. This leads to words such as difficult sounding like typical to the American ear. When a Korean speaker says a word from the F column, it’s likely to be heard by Americans as being from the P column. (See also Chapter 19.)

|

æ |

The exact æ sound doesn’t exist in Korean; it’s close to ε, so bat sounds like bet. You need to raise the back of your tongue and drop your jaw to produce this sound. Work on Chapter 3, which drills this distinctively American vowel. (See also Chapters 12, 18, and 20.) |

ä |

The ä sound is misplaced. You have the ä sound when you laugh hahaha |

o |

You may pronounce the letter o as ä or ә when it really should be an ō, as in only, most, both. Make sure that the American o sounds like ou: ounly, moust, bouth. This holds true for the diphthongs as well—oi sounds like o-u-ee. (See also Chapters 12, 18, and 20.)

|

ә |

The schwa is typically overpronounced, based on spelling. Concentrate on smoothing out and reducing the valleys and ignore spelling! (See also Chapters 12, 18, and 20.) |

ü |

Distinguishing tense and lax vowels is difficult, and you’ll have to forget spelling for u and ü. They both can be spelled with oo or ou, but the lax vowel ü should sound much closer to i or uh. If you say book with a tense vowel, it’ll sound like booque. It should be much closer to bick or buck. (See also Chapters 18 and 20.) |

i |

Similarly, you need to distinguish between e and i, as in beat and bit. Tone down the middle i in multisyllabic words, as in Chapter 18, otherwise, beautiful byoo•d’•fl will sound like byoo-tee-fool. Most likely, you overpronounce the lax vowel i to eee, so sit is overpronounced to seat. Reduce the soft i to a schwa; sit should sound like s’t. In most Korean dictionaries, the distinction between i and ē is not made. Practice the four sounds—bit, beat, bid, bead—remembering that tense vowels indicate that you tense your lips or tongue, while lax vowels mean that your lips and tongue are relaxed and the sound is produced in your throat. Unvoiced final consonants (t, s, k, p, ch, f) mean that the vowel is short and sharp; voiced final consonants (d, z, g, b, j, v) mean that the vowel is doubled. Work on Bit or Beat? Bid or Bead? in Chapter 18. (See also Chapter 20.)

|

The Korean R = The American T

The Korean r is a consonant. This means that it touches at some point in the mouth. Korean speakers usually trill their r’s (tapping the ridge behind the top teeth), which makes it sound like a d to the American ear. The tongue should be curled back, and the r produced deep in the throat—not touching the top of the mouth. The Korean pronunciation of r is usually just an ä at the end of a word (car sounds like caaah) or a flap in the beginning or middle (area sounds like eddy-ah). (See also Chapter 14.)

Though there are several dialects in Arabic, from the Levantine dialect of Jordan, Palestine, Lebanon, and Syria to the dialect specific to the Gulf States, as well as the regional differences in Iraq, Egypt, and Libya, there remains a common accent thread in Arabic speakers. Especially noticable in those who have had little prior exposure to English or other Western languages, the accent is typified by a leaden intonation and the lack of several key consonants and vowels. (See also Chapters 3 and 4.)

Intonation

The overall intonation can be perceived as leaden, as it’s rather heavy and non-musical. Syllable stress is also an issue as non-standard syllables are stressed, such as in subséquent and dévelopment. When the Arabic speaker is unaware of the rules of American intonation, there is a tendency to simply guess where intonation goes. As a result, intonation pretty much lands on every other word, greatly confusing the American listener. (See Chapter 4.)

Liaisons

This is a category that causes confusion for Arabic speakers, resulting in comprehension and pronunciation problems. Because Americans tend to connect all their words, many Arabic speakers are not sure where one word ends and the next begins. Relying on the phonetic transcriptions of phrases and sentences teaches the Arabic speaker the construction of American liaisons. Also, simple rules like T + Y = CH is tremendously helpful with high-frequency phrases such as “Got you,” pronounced “Gotcha.” (See also Chapter 11.)

Pronunciation

There is no ambiguity in pronouncing words in Arabic, and because of that, there’s a very strong tendency to carry this purely phonetic concept over to the wilds of English where -ough can be pronounced cough, through, enough, though, and thought. Phonetics are the problem; phonetics are the solution. Because the concept of phonetics is so strong in the Arabic psyche, reliance on the phonetic transcription will be very useful.

Word Endings

Arabic speakers overstress the final consonant. At times it can be surprising to an American listener, as it sounds overly emphatic or emotional. The idea of an “unvoiced” final consonant is new to Arabic speakers. Listening carefully to the exercises dealing with unvoiced final consonants, recording yourself, and repeating, will address this issue. Liaisons will assist with word endings.

The Arabic R

The Arabic R is a single trill of the tongue tip on the alveolar ridge, which ends up sounding like a D or a middle T to the American ear. The final R also tends to pick up the preceding vowel, so her sounds like hair, verb like vairb, were like where. To the American ear, the initial R is like five Ds fluttered in a row. Making sure that the tongue has no contact with the rest of the mouth is the start of the process for the American R.

The Arabic T

All Ts are popped, regardless of the position in the word. The T at the beginning of a word doesn’t typically have the necessary puff of air, and a tssh sound should be added.

Conversely, middle Ts should be changed to D, as in authority (authoridy), or dropped completely as in twenty or identity (twenny and idenadee).

In particular, the word To should be changed to duh, as in day to day (day da day) or like to mention (like duh mention). The final T should be held in for risk of sounding tense or annoyed. The held T before N is also usually popped, and should be held, instead, as in important, written, forgotten.

Although there are two TH sounds in Arabic, this often ends up sounding like a D. The tongue tip needs to be about a half inch more forward, either against the back of the teeth or on the biting edge, but definitely not on the ridge.

Middle I

Arabic speakers tend to overpronounce this sound, and instead should reduce it to a schwa.

V

The V sound doesn’t exist in Arabic, and is often replaced with an F.

P

The P sound doesn’t exist in Arabic, and is often replaced with a B, resulting in brivate, broblem, beeble. A joke making the rounds is “Officer, may I blease bark here?” “Sure, you can bark anywhere!”

F |

V |

B |

F |

V |

B |

fat |

vat |

bat |

ferry |

very |

berry |

face |

vase |

base |

effort |

ever |

Ebber |

fear |

veer |

beer |

foul |

vowel |

bowel |

G

The G is an interesting and important sound in Arabic, as it’s the one dealing with the problematic spelling of Ghaddafi, Khaddafi, Qhaddafi. Given that Arabic is considered a gutteral language, this is a very noticeable sound. Especially the soft G, which is hardened, so bring it sounds like bring git.

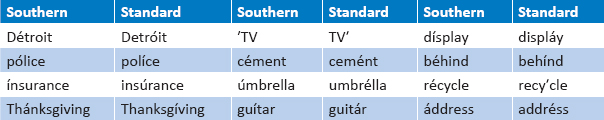

Granted, the American South, the land of the lilting drawl, encompasses a lot of geography, and to the denizens there are very clear regional distinctions. We are not going to address that here, but rather give some general guidelines on standardizing the accent. Clearly, the predominant characteristic is the duration of the vowels. Clipped Yankee vowel durations can sound snippy, rude, or cold to a southerner, so there may be a little psychological resistance to shortening them up. To a northerner, these shortened vowels sound completely neutral.

Intonation

Word stress can be different from standard speech, with emphasis on the first syllable. (See also Chapter 4.)

Word Endings

A classic southernism is the dropped g of ing. This can be changed in two ways. The standard way is to bring up the back of the tongue until it meets the soft palate. The other way is the Californian -een, so running sounds like runneen. Practice with Mr. Manning was being confusing as he was running, jumping, and singing. (See also Chapter 11.)

The final D is dropped in understand: unnerstan’, friend: fren’, and so on. In terms of vowel duration, the vowels are often lengthened with a lilt, but with final voiced consonants, the last consonant is devoiced, so that job sounds more like jop, and and did like dit.

The -ed Ending

When there is a voiced consonant followed by -ed, you need vocalize the D. Otherwise, it can sound like a T, such as The deer was killt as it crossed the tracks. (See also Chapter 14.)

Pronunciation

Consonants are similar to standard American, but vowels tend to be doubled or even tripled. If you just change the long I from ah to äi, round off the final R and don’t add an extra syllable after the æ sound, you’ll make a major change in how you sound. (See also Chapter 3.)

The Southern R

The Southern R (or lack thereof) is most noticeable at the end of a word, where it sounds more like a schwa than an R, as Put the paypuh upstayuhz. Use a growly RRRR to finish off these words, so it sounds like Put the paperrrr upstairrrrrs. Make sure that sure doesn’t sound like shore. Don’t let hair and there become hayuh and they-uh. Practice with Therrrrre arrrre fourrrrr shorrrrrrt hairrrrrs overrrrr therrrrrre. Yes, you’ll sound a little like a pirate.

You’ll also want to make a clear distinction between card (cärd) / cord (kord), far (fär) / for (for), farm (färm) / form (form). (See also Chapter 15.)

æ |

Resist adding an extra syllable to cat (cayut), can (cayan), pan (payan). Make sure that can’t doesn’t sound like cain’t and the æo in about doesn’t come out as abat. Practice: Jack sat back, drank from his glass, and laughed about how it sounded . . . (See also Chapters 12, 18, and 20.) |

Long i |

This is a classic sound associated with the South, where My eye sounds like Mah aahh. What’s going on is that the first half of the äi sound is elongated and the second half gets dropped off. Practice these sentences: I’m tired. I’d like a nice slice of lime pie. (See also Chapters 12, 18, and 20.) |

ü |

The ü sound can either be elongated from book to buuhk, or turned into an ih sound, a good cook sounds like a gid kick. (See also Chapters 18 and 20.) Practice with this sentence: I took a good look at the cook book. A Northerner was driving through the South and heard advertisements on the radio, and was surprised that someone was selling an automobile and four guitars. Listening further, he realized of course, that it was a car with four good tires. |

ih |

The ih sound can go in three directions. Words like pin are often pronounced pen, again / agin, get / git. Also, ih can sound like æ, thing / thang and drink / drank. For this, try saying it theeng and dreenk. Third, it can also turn into a lilting E sound, with Bill sounding like Beel. Practice this sentence: Bill filled his thin pen again. (See also Chapters 18 and 20.) |

ε |

Resist adding an extra syllable to bed (beyed), pet (peyet), next (nayext). Practice with this sentence: Jeb gets to help the next pet. (See also Chapters 12, 18, and 20.) |

o |

Try not rounding and extending the ah sound so much, so dog doesn’t sound like dawg, nor talk like tawk. Practice this sentence: Bob talked about John’s dog all along the walk with Tom. This should all have the same ah sound in every word: Bahb tahkt about Jahnz dahg ahl alahng the wahk with Tahm. Think of a ventriloquist’s dummy, where your jaw just clacks up and down. (See also Chapters 12, 18, and 20.) |

ee |

Make sure that the ee sound doesn’t relax into the ih, so I feel good doesn’t sound like I fill good. (See also Chapter 20.) |

ә |

As you saw in the R section, this neutral vowel is commonly used to replace -er and -or. Practice saying favrrr (favor) instead of favuh, and rathrrrr (rather) instead of rathuh. Practice sentence: Her cars were over there. (See also Chapters 12, 18, and 20.) |

oi |

This should be two full vowels. The southern boy almost sounds like boa. Practice with Joy’s boy toy foiled the royal oil ploy. (See also Chapter 20.) |

Z |

The Z sound (spelled with an S) turns to a D before N. That dudn’t make sense. It just idn’t right. It’s a good bidness, innit? That wadn’t what happened. Practice putting in buzzy Zs: He duzzzzen know, duzzzzy? It wazzzzen any good, wuzzzzzzit? (See also Chapter 17.) |

L |

Make sure to pronounce the L in help and values so that it doesn’t sound like Hep yoursef, and va-yoos. |

Vocabulary

Modal stacking is particular to the South. I used to could do it. You might could send them an email. You might should tell her about it. Leave either one of them off.

Y’all can be changed to you guys, everyone, everybody or just plain you. (Make sure to say everybody, not ever’body).

Fixing to is more readily recognizable as getting ready to.

Done can be omitted in I done told you about it! or I done had lunch.

Make sure to change doin’ good to doing well.

Intonation