In the late nineteen-sixties, I was working in rented space on Nassau Street up a flight of stairs and over Nathan Kasrel, Optometrist. Across the street was the main library of Princeton University. Across the hall was the Swedish Massage. Operated by an Austrian couple who were nearing retirement and had been there for decades, it was a legitimate business. They massaged everything from college football players to arthritic ancients, and they didn’t give sex. This, however, was the era when massage became a sexual synonym, and most evenings—avoiding writing, looking down from my window on the passing scene—I would see men in business suits stop, hesitate, look around, and then move toward the glass door at the foot of the stairs. Eventually, the Austrians had to scrape the words “Swedish Massage” off the door, and replace them with a hanging sign they removed when they went home at night. Meanwhile, the men kept arriving at the top of the stairs, where neither door was marked. When they knocked on mine and I opened it, their faces fell dramatically as the busty Swede they expected turned into a short and bearded man.

In this context, I wrote three related pieces that became a book called Encounters with the Archdruid. To a bulletin board I had long since pinned a sheet of paper on which I had written, in large block letters, ABC/D. The letters represented the structure of a piece of writing, and when I put them on the wall I had no idea what the theme would be or who might be A or B or C, let alone the denominator D. They would be real people, certainly, and they would meet in real places, but everything else was initially abstract.

That is no way to start a writing project, let me tell you. You begin with a subject, gather material, and work your way to structure from there. You pile up volumes of notes and then figure out what you are going to do with them, not the other way around. In 1846, in Graham’s Magazine, Edgar Allan Poe published an essay called “The Philosophy of Composition,” in which he described the stages of thought through which he had conceived of and eventually written his poem “The Raven.” The idea began in the abstract. He wanted to write something tonally sombre, sad, mournful, and saturated with melancholia, he knew not what. He thought it should be repetitive and have a one-word refrain. He asked himself which vowel would best serve the purpose. He chose the long “o.” And what combining consonant, producibly doleful and lugubrious? He settled on “r.” Vowel, consonant, “o,” “r.” Lore. Core. Door. Lenore. Quoth the Raven, “Nevermore.” Actually, he said “nevermore” was the first such word that crossed his mind. How much cool truth there is in that essay is in the eye of the reader.

Nonetheless, I was doing something like it when I put ABC/D on the wall. For more than a decade, first at Time magazine and then at The New Yorker, I had been writing profiles—each, by definition, portraying an individual. At Time, I did countless sketches, long and short, of show-business people (Richard Burton, Sophia Loren, Barbra Streisand, et al.), and at The New Yorker even longer pieces, on an athlete, a headmaster, an art historian, an expert on wild food. After ten years of that, I was a little desperate to escalate, or at least get out of a groove that might turn into a rut.

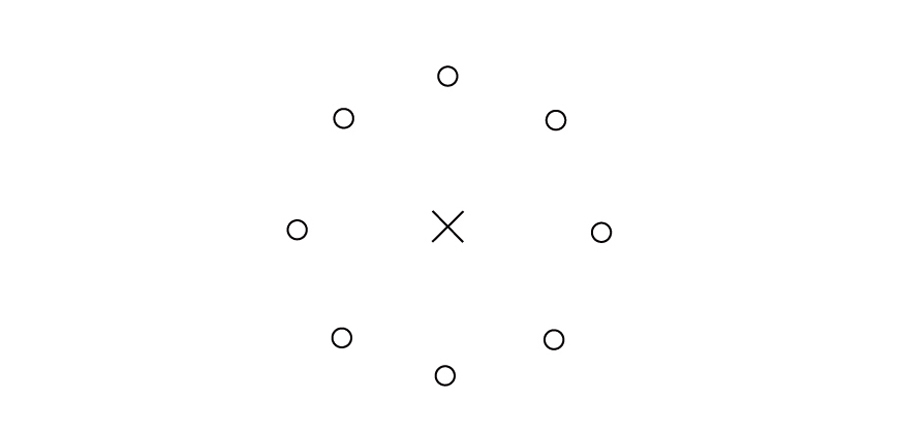

To prepare a profile of an individual, the reporting endeavor looks something like this:

The X is the person you are principally going to talk to, spend time with, observe, and write about. The O’s represent peripheral interviews with people who can shed light on the life and career of X—her friends, or his mother, old teachers, teammates, colleagues, employees, enemies, anybody at all, the more the better. Cumulatively, the O’s provide triangulation—a way of checking facts one against another, and of eliminating apocrypha. Writers like Mark Singer and Brock Brower have said that you know you’ve done enough peripheral interviewing when you meet yourself coming the other way.

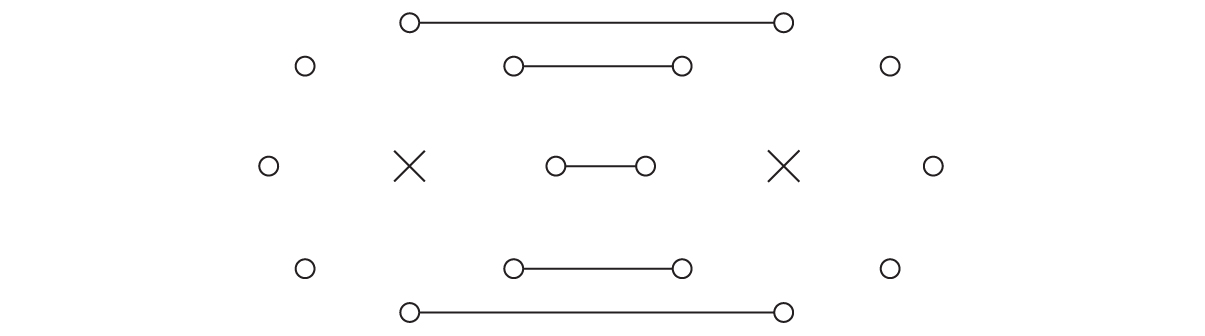

So, after those ten years and feeling squeezed in the form, I thought about doing a double profile, through a process like this:

In the resonance between the two sides, added dimension might develop. Maybe I would twice meet myself coming the other way. Or four times. Who could tell what might happen? In any case, one plus one should add up to more than two.

Then who? What two people? I thought of various combinations: an actor and a director, a pitcher and a manager, a dancer and a choreographer, a celebrated architect and a highly successful bullheaded client, 1 + 1 = 2.6. One day while I was still undecided, I happened to watch on CBS a men’s semifinal in the first United States Open Tennis Championships. Two Americans—one of them twenty-five years old, the other twenty-four—were playing each other. One was white, the other black. One had grown up beside a playground in inner-city Richmond, the other on Wimbledon Road in Cleveland’s wealthiest suburb. On their level are so few tennis players—and the places they compete are so organized nationally—that these two would have known each other since they were eleven years old. For something like three weeks, I kept thinking about that combination and its possibilities, and then decided to attempt a double portrait, letting the match itself contain and structure the story. I would not be able to do that without a copy of the CBS tape. In those days, tapes were not archived. They saw repeated use. The copying would have to be done as something called a kinescope—a sixteen-millimeter film shot from a television monitor. I asked William Shawn, The New Yorker’s editor, if he would pay for the kinescope. “Very well,” he said, sighing. “Go ahead.” I called CBS. A guy there said, “You haven’t called a minute too soon. That tape is scheduled to be erased this afternoon.”

Called “Levels of the Game,” the double profile worked out, and my aspirations went into a vaulting mode. If two made sense, why not four people in one complex piece of writing? That was when I put the block letters on the bulletin board. A, B, and C would be separate from one another, and each would interact with D, yes, but who were these people? As things would eventuate, the two projects I am describing—1 + 1 = 2.6 and ABC/D—would be the only ones I would ever do that began as abstract expressions in search of subject matter. Quoth the raven, “Nevermore.” Meanwhile, there was still no theme for the quadripartite profile. What to write about?

As I have noted in (among other places) the introduction to a book of excerpts called Outcroppings, a general question about any choice of subject is, Why choose that one over all other concurrent possibilities? Why does someone whose interest is to write about real people and real places choose certain people, certain places? For nonfiction projects, ideas are everywhere. They just go by in a ceaseless stream. Since you may take a month, or ten months, or several years to turn one idea into a piece of writing, what governs the choice? I once made a list of all the pieces I had written in maybe twenty or thirty years, and then put a check mark beside each one whose subject related to things I had been interested in before I went to college. I checked off more than ninety per cent.

My father was a medical doctor who dealt with the injuries of Princeton University athletes. He also travelled the world as the chief physician of several United States Olympic teams. When I was very young, he spent summers as the physician at a boys’ camp in Vermont. It was called Keewaydin and was a classroom of the woods. It specialized in canoe trips and taught ecology in our modern sense when the word was still connoting the root-and-shoot relations of communal plants. Aged six to twenty, I grew up there, ending as a leader of those trips. I played basketball and tennis there, and on my high-school teams at home, with absolutely no idea that I was building the shells of future pieces of writing. I dreamed all year of the trips in the wild, not imagining, of course, that they would eventually lead to the Brooks Range, to the Yukon-Tanana suspect terrain, to the shiplike ridges of Nevada and the Laramide mountains of Wyoming, or that they would lead to the rapids of the Grand Canyon in the company of C over D.

The environmental movement was in its early stages in the nineteen-sixties, and I decided that it would be the subject of ABC/D, pitting an environmentalist against three natural enemies. Easier said than arranged. I still had no inkling who these people might be. In fact, if their names had somehow magically appeared before me I would not have recognized any of them. For help, I went to Washington, where my friend John Kauffmann, with whom I had once taught school, worked for the National Park Service as a planner. Components of the park system that have resulted from his studies are, among others, Cape Cod National Seashore and Gates of the Arctic National Park. With several of his colleagues and friends, we developed lists of possibilities, first for D. We were looking for people in the category of the late Aldo Leopold, “the father of wildlife ecology,” whose A Sand County Almanac had sold two million copies; but he would have been too reasonable, as were other leading environmentalists of the day, with a bristly exception. David Brower, executive director of the Sierra Club, was described by Kauffmann and company as a feisty take-no-prisoners unilateral thinker with tossing white hair like a Pentateuchal prophet. He had a phone number in area code 415. I called him up. Several days later, he called back to say that he would do it. Meanwhile, A, B, and C—the three natural enemies—were easier to identify than to choose, and, seeking no input whatever from Brower, we made a list of seventeen. Several months later, it had been reduced to three, and among them was Floyd Dominy, the United States Commissioner of Reclamation. He built very big Western dams, and he was a very tough Western guy. As a young county agent in Wyoming, he had helped ranchers through drought after drought, and he deeply believed in the impoundment of water. In congressional hearings, he had fought Dave Brower over potential dam sites from Arizona to Alaska, and now and again Brower had defeated him. Dominy looked upon Brower as a “selfish preservationist.” In an early interview at Dominy’s office in the Department of the Interior, he said to me, “Dave Brower hates my guts. Why? Because I’ve got guts.” As that conversation would play out in the eventual piece, Dominy went on to say,

“I can’t talk to Brower, because he’s so God-damned ridiculous. I can’t even reason with the man. I once debated with him in Chicago, and he was shaking with fear. Once, after a hearing on the Hill, I accused him of garbling facts, and he said, ‘Anything is fair in love and war.’ For Christ’s sake. After another hearing one time, I told him he didn’t know what he was talking about, and said I wished I could show him. I wished he would come with me to the Grand Canyon someday, and he said, ‘Well, save some of it, and maybe I will.’ I had a steer out on my farm in the Shenandoah reminded me of Dave Brower. Two years running, we couldn’t get him into the truck to go to market. He was an independent bastard that nobody could corral. That son of a bitch got into that truck, busted that chute, and away he went. So I just fattened him up and butchered him right there on the farm. I shot him right in the head and butchered him myself. That’s the only way I could get rid of the bastard.”

“Commissioner,” I said, “if Dave Brower gets into a rubber raft going down the Colorado River, will you get in it, too?”

“Hell, yes,” he said. “Hell, yes.”

C plus D, then—that was the general idea of Encounters with the Archdruid. With A and B (Charles Park, a mining geologist, and Charles Fraser, a resort developer), the four profiles in three parts worked out about as well as 1 + 1 had done. So, at risk of getting into an exponential pathology, I began to think of a sequence of six profiles in which a seventh party would appear in a minor way in the first, appear again in greater dimension in the second, grow further in the third, and further in the fourth, fifth, and sixth, always in subordinate ratio to the principal figure in each piece until becoming the central figure in a seventh and final profile. However, I backed away from this chimerical construction, just as I once backed away from Mr. Shawn after he asked me to stop by his office and suggested that I look into what it costs to run hospitals in New York from the first Band-Aid to the last bedpan. In Tina Brown’s first year as editor of The New Yorker, she suggested that I shelve the piece I was working on, and write about murder in the Strait of Malacca. I demurred. Those were the only two times in half a century that The New Yorker has offered me an assignment.

Readers are not shy with suggestions, and the suggestions are often good but also closer to the passions of the reader than to this writer’s. A sailor named Andy Chase wrote to me from the deck of a tanker, describing the grave decline of the U.S. Merchant Marine and detailing its present and historical importance. Yawn. Then he said he felt sure that I couldn’t give a rat’s ass for the fate of the Merchant Marine, but if I were to come out on the ocean with merchant mariners I would meet outspoken characters I would love to sketch. When he was ashore, I visited him at his home, in Maine, and found myself scribbling notes all day. Before long, he and I were visiting union halls in New York, Charleston, and Savannah, looking for a ship. After Looking for a Ship was published, a letter came from a truck driver, another complete stranger, who owned his own chemical tanker. He said, “If you can go out on the ocean with those people, you should come out on the road with us.” I wrote back, “Tell me what you do.” On a legal pad, while his tank was getting an interior wash, he wrote seven pages saying where he went with what. I corresponded with him for five years but didn’t actually meet him until a day came when I got into his truck in Georgia. He said, right off, “Now, this may not work out. If it doesn’t, I completely understand. Just tell me, and I’ll drop you off at an airport anywhere on my route.” I got out of his truck in Tacoma. In a lifetime of good suggestions arriving in the mail from ordinary readers, those are the only two I ever acted on.

Ideas are where you find them, and John Kauffmann, meanwhile, was feeding them to me as if he were making foie gras. John grew up in summers in northern New Hampshire in canoes, and we had so many common interests that ultimately about twenty per cent of my books would owe themselves in whole or in some part to his ideas—Encounters with the Archdruid, The Survival of the Bark Canoe, and Coming into the Country, among others. Even more so, however, new pieces can shoot up from other pieces, pursuing connections that run through the ground like rhizomes. Set one of these progressions in motion, and it will skein out in surprising ways, finally ending in some unexpected place.

In 1969, the year I spent with David Brower, he left his redwood house in Berkeley one day to fly upstate to Eureka and attend the dedication of Lady Bird Johnson Grove, in Redwood National Park. He took me with him. In the shadowy, columnar woods, we hiked in on a newly constructed driveway paved with redwood chips. Now and again, a slow black limousine overtook and passed us. Secret Service men in black suits walked beside the limos. At regular intervals along the way, red telephones stood up surreally above the ferns—landline desk telephones of the three-pound push-button vintage, unsheltered, each resting on a square redwood board supported by a redwood stake. While most attendees walked into the grove, the President of the United States and the immediate-past President of the United States and a future President of the United States and Senator George Murphy and Billy Graham and Lady Bird and Pat and Nancy rolled through in the limos on the chips. The ceremony took place on a redwood platform, elevating the presidents to a level unimpressive in the landscape. California’s Governor Reagan spoke pleasant words of welcome and kept to himself his established opinion that if you’ve seen one redwood you’ve seen them all. Richard Nixon had much to say, much of which was lost on Lyndon Johnson, seated nodding on the platform and before long so sound asleep that his mouth fell open wider than a golf ball.

Afterward, at the airport in Eureka, Brower introduced me to George Hartzog, director of the National Park Service, who happened to be standing behind us in a long line of people waiting for a flight to San Francisco. At the moment, he told Brower, he was particularly interested in the Buffalo River in Arkansas, because he wanted to get hold of it before the Corps of Engineers did, or before developers did, or before the state mucked it up. He wanted the Buffalo to become the nation’s first National River. He said he had little time for fishing now, except in streams near the capital, but he thought he would try to spend a few days on the Buffalo and look the river over. Brower had about as much interest in fishing as he had in impounding water. I, though, surprised myself (because I am shy to the point of dread) by blurting out to George Hartzog, “Would you take me with you?”

He did. And he agreed to be the subject of a New Yorker profile. And he brought his friend Tony Buford along on the river. The Buffalo, alas, was swollen four feet above its normal level, and the fishing was poor, bringing out in the two friends a polarity of reaction. Buford was a self-educated Missouri lawyer who had become the general counsel of Anheuser-Busch and raised quarter horses on his farm, in the southeastern part of the state. Hartzog, a licensed preacher who grew up in poverty in Smoaks, South Carolina, had also studied law on his own, and had passed the South Carolina bar. He and Buford had become friends when Hartzog was the chief Park Service ranger stationed in St. Louis to initiate the construction of the Gateway to the West—the Eero Saarinen arch. Hartzog, in effect, was the on-site representative of the client, and if you go there today and wish to ride to the top you will buy your ticket in the George B. Hartzog Visitor Center.

It was Hartzog who took a set of plans that had been lying dormant for fifteen years and built the great arch of St. Louis. Those who know the story of the arch say that had it not been for Hartzog there would be no arch. Hartzog the Ranger is a hero in St. Louis, but at this moment he is not a hero to Tony Buford. “God damn it, George, this river is a mess. There is no point fishing this God-damned river, George. The fishing is no good.”

Hartzog looks at Buford for a long moment, and the expression on his face indicates affectionate pity. He says, “Tony, fishing is always good.” The essential difference between these friends is that Buford is an aggressive fisherman and Hartzog is a passive fisherman. Spread before Buford on the bow deck of his johnboat is an open, three-tiered tackle box that resembles the keyboard of a large theatre organ.

Buford filled a lot of his fishless time talking about the All-American Futurity, an annual race for two-year-old quarter horses in Ruidoso, New Mexico, toward which he aimed his efforts as a breeder. Its purse was nearly double the combined purses of the Kentucky Derby, the Preakness, and the Belmont Stakes, and was assembled in a kind of chain letter among quarter-horse breeders, involving the early registration of more than a thousand one-year-olds and incremental payments due every couple of months, like property taxes, and rising even faster. “You should come out to New Mexico and write about it,” Buford said to me, and soon said it again. I didn’t know a horse from a zebra, but before long he said it again, and—in campsites as on the river—again. “You should come out to New Mexico and write about the All-American.”

None of Buford’s horses showed adequate promise for the next All-American, and he scratched out and stayed home while I went to Ruidoso with my wife, Yolanda Whitman. She had grown up on horses in Connecticut, and pretty much knew what was going on when we went to the barns each day for two weeks, arriving sometimes before dawn. Quickly, we gravitated to Bill H. Smith, of Pea Ridge, Arkansas, who was there to take on the super-rich “Texas-buckled sons of bitches” from Oklahoma, California, and the aforementioned state. Those words did not belong to Bill H. Smith but to Dean Turpitt, the official starter, who played himself in the movie. His role in real life was huge. Quarter horses are much faster than Thoroughbreds, and a third of a minute after he opened the gate their quarter-mile races were over. A quarter horse had been clocked at fifty-five miles an hour, the world record for racehorses of any kind. From trial heats a week beforehand, in which every horse was timed no matter where it finished, the ten fastest horses at Ruidoso moved on to the final. Smith had a horse named Calcutta Deck, who made it to the final. In the last days and hours before the race, I was torn by conflicting emotions. Strongly, I wanted Deck to win for Bill H. Smith. Even more strongly, I wanted Deck to lose, because in doing so he would provide a better story. As I went to the rail to watch the race, I was literally split dizzy.

* * *

As it happened, there was one more stop in the cul-de-sac of this Levels–Archdruid–Ruidoso progression. Now and again through the years, people had called about film rights for my nonfiction stories, typically in the dead of night when some independent producer three time zones west had just finished reading The New Yorker. The calls had ceased to excite. I decided early that nothing comes of them. For the producer, the next stop would be a bank or a studio and he or she was never heard from again. The closest I had come was when a producer of both movies and television series optioned Levels of the Game. We met in New York, and he said he was going to rent the tennis stadium at Forest Hills and fill it up with extras. He filled it up with nothing, and even failed to meet his payment for the option.

After “Ruidoso” appeared in The New Yorker, there was a call from the producer Ray Stark, and this time (but nevermore) something came of it. Stark’s Rastar Productions actually made a movie, titled Casey’s Shadow, that starred actors celebrated at the time, Alexis Smith and Walter Matthau. Because I imagined that the film would not resemble the piece I had written, I asked that my name not appear in the credits. When Casey’s Shadow came to the Prince Theater on U.S. 1 outside Princeton, Yolanda and I took our kids to see it. Between us, we had eight kids, most of whom were along. I settled into my seat and watched, and settled even farther, as I generally do, and by the end of the movie I was so slumped down I was all but flat on my back. With structural fidelity, the piece was telling the story I had written, changing little: Matthau came from quarter-horse country in Louisiana instead of Arkansas. For some reason, I had in my pocket an unusual number of coins, a whole lot of coins, and in the course of the movie the coins leaked out and fell in darkness to the floor. As the movie ended and the credits began to roll, I turned my back to the screen, got down on my hands and knees, and felt around for the coins. Suddenly, there was an outburst of applause from my children. Evidently, the credits had said “This picture is based upon … ‘Ruidoso’ by John McPhee” while I was on the floor groping under the seat for nickels, dimes, and pennies.