Out the back door and under the big ash was a picnic table. At the end of summer, 1966, I lay down on it for nearly two weeks, staring up into branches and leaves, fighting fear and panic, because I had no idea where or how to begin a piece of writing for The New Yorker. This was three and a half years before the progression described in the previous chapter. I went inside for lunch, surely, and at night, of course, but otherwise remained, much of that time, flat on my back on the table. The subject was the Pine Barrens of southern New Jersey. I had spent about eight months driving down from Princeton day after day, or taking a sleeping bag and a small tent. I had done all the research I was going to do—had interviewed woodlanders, fire watchers, forest rangers, botanists, cranberry growers, blueberry pickers, keepers of a general store. I had read all the books I was going to read, and scientific papers, and a doctoral dissertation. I had assembled enough material to fill a silo, and now I had no idea what to do with it. The piece would ultimately consist of some five thousand sentences, but for those two weeks I couldn’t write even one. If I was blocked by fear, I was also stymied by inexperience. I had never tried to put so many different components—characters, description, dialogue, narrative, set pieces, humor, history, science, and so forth—into a single package.

It reminded me of Mort Sahl, the political comedian, about whom, six years earlier, I had written my first cover story at Time magazine. The scale was different. It was meant to be only five thousand words and a straightforward biographical sketch, appearing during the Kennedy-Nixon presidential campaigns, but the five thousand words seemed formidable to me then. With only a few days to listen to recordings, make notes, digest files from Time correspondents, read morgue clippings, and skim through several books, I was soon sprawled on the floor at home, surrounded by drifts of undifferentiated paper, and near tears in a catatonic swivet. As hour followed hour toward an absolute writing deadline (a condition I’ve never had to deal with at The New Yorker), I was able to produce only one sentence: “The citizen has certain misgivings.” So did this citizen, and from all the material piled around me I could not imagine what scribbled note to take up next or—if I figured that out—where in the mess the note might be.

In my first three years at Princeton High School, in the late nineteen-forties, my English teacher was Olive McKee, whose self-chosen ratio of writing assignments to reading assignments seems extraordinary in retrospect and certainly differed from the syllabus of the guy who taught us in senior year. Mrs. McKee made us do three pieces of writing a week. Not every single week. Some weeks had Thanksgiving in them. But we wrote three pieces a week most weeks for three years. We could write anything we wanted to, but each composition had to be accompanied by a structural outline, which she told us to do first. It could be anything from Roman numerals I, II, III to a looping doodle with guiding arrows and stick figures. The idea was to build some form of blueprint before working it out in sentences and paragraphs. Mrs. McKee liked theatrics (she was also the school’s drama coach), and she had us read our pieces in class to the other kids. She made no attempt to stop anybody from booing, hissing, or wadding paper and throwing it at the reader, all of which the kids did. In this crucible, I learned to duck while reading. I loved Mrs. McKee, and I loved that class. So—a dozen years later, when Mort Sahl was overwhelming me, and I was wallowing in all those notes and files—I thought of her and the structure sheets, and despite the approaching deadline I spent half the night slowly sorting, making little stacks of thematically or chronologically associated notes, and arranging them in an order that seemed to hang well from that lead sentence: “The citizen has certain misgivings.” Then, as I do now, I settled on an ending before going back to the beginning. In this instance, I let the comedian himself have the last word: “‘My considered opinion of Nixon versus Kennedy is that neither can win.’”

The picnic-table crisis came along toward the end of my second year as a New Yorker staff writer (a euphemistic term that means unsalaried freelance close to the magazine). In some twenty months, I had submitted half a dozen pieces, short and long, and the editor, William Shawn, had bought them all. You would think that by then I would have developed some confidence in writing a new story, but I hadn’t, and never would. To lack confidence at the outset seems rational to me. It doesn’t matter that something you’ve done before worked out well. Your last piece is never going to write your next one for you. Square 1 does not become Square 2, just Square 1 squared and cubed. At last it occurred to me that Fred Brown, a seventy-nine-year-old Pine Barrens native, who lived in a shanty in the heart of the forest, had had some connection or other to at least three-quarters of those Pine Barrens topics whose miscellaneity was giving me writer’s block. I could introduce him as I first encountered him when I crossed his floorless vestibule—“Come in. Come in. Come on the hell in”—and then describe our many wanderings around the woods together, each theme coming up as something touched upon it. After what turned out to be about thirty thousand words, the rest could take care of itself. Obvious as it had not seemed, this organizing principle gave me a sense of a nearly complete structure, and I got off the table.

Structure has preoccupied me in every project I have undertaken since, and, like Mrs. McKee, I have hammered it at Princeton writing students across decades of teaching: “You can build a strong, sound, and artful structure. You can build a structure in such a way that it causes people to want to keep turning pages. A compelling structure in nonfiction can have an attracting effect analogous to a story line in fiction.” Et cetera. Et cetera. And so forth, and so on.

The approach to structure in factual writing is like returning from a grocery store with materials you intend to cook for dinner. You set them out on the kitchen counter, and what’s there is what you deal with, and all you deal with. If something is red and globular, you don’t call it a tomato if it’s a bell pepper. To some extent, the structure of a composition dictates itself, and to some extent it does not. Where you have a free hand, you can make interesting choices—for example, when I was confronted with the even more complicated set of notes resulting from twelve months of varied travels with the four principal participants in Encounters with the Archdruid. The simplified, conceptual structure ABC/D now needed filling in. There would be three sections narrating three journeys: A, in the North Cascades with Charles Park, the mining geologist; B, on a Georgia island with Charles Fraser, the resort developer; C, on the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon with Floyd Dominy, builder of huge dams. D—David Brower, the high priest of the Sierra Club—would be in all three parts. Biographical descriptions of the others would of course belong in the relevant sections, but in the stories of the three journeys the details of Brower’s life could go anywhere. When I was through studying, separating, defining, and coding the whole body of notes, I had thirty-six three-by-five cards, each with two or three code words representing a component of the story. All I had to do was put them in order. What order? An essential part of my office furniture in those years was a standard sheet of plywood—four by eight feet—on two sawhorses. I strewed the cards face-up on the plywood. The anchored segments would be easy to arrange, but the free-floating ones would make the piece. I didn’t stare at those cards for two weeks, but I kept an eye on them all afternoon. Finally, I found myself looking back and forth between two cards. One said “Alpinist.” The other said “Upset Rapid.” “Alpinist” could go anywhere. “Upset Rapid” had to be where it belonged in the journey on the river. I put the two cards side by side, “Upset Rapid” to the left. Gradually, the thirty-four other cards assembled around them until what had been strewn all over the plywood was now in neat rows. Nothing in that arrangement changed across the many months of writing.

The Colorado River in the Grand Canyon had several rapids defined on our river maps as “cannot be run without risk of life,” Upset Rapid among them. We were in a neoprene raft with a guide named Jerry Sanderson, and by rule he had to stop and study the heavier rapids before proceeding down them. For several days, Brower and Dominy had been engaged in verbal artillery over Dominy’s wish to build high dams in the middle of the Grand Canyon. They fought all day and half the night, while I scribbled notes. Now,

We all got off the raft and walked to the edge of the rapid with Sanderson.… The problem was elemental. On the near right was an enormous hole, fifteen feet deep and many yards wide, into which poured a scaled-down Canadian Niagara—tons upon tons of water per second. On the far left, just beyond the hole, a very large boulder was fixed in the white torrent.…

“What are you going to do about this one, Jerry?”

Sanderson spoke slowly and in a voice louder than usual, trying to pitch his words above the roar of the water. “You have to try to take ten per cent of the hole. If you take any more of the hole, you go in it, and if you take any less you hit the rock.”

“What’s at the bottom of the hole, Jerry?”

“A rubber raft,” someone said.

Sanderson smiled.

“What happened two years ago, Jerry?”

“Well, the man went through in a neoprene pontoon boat, and it was cut in half by the rock. His life jacket got tangled in a boat line and he drowned.…”

We got back on the raft and moved out into the river. The raft turned slowly and began to move toward the rapid. “Hey,” Dominy said. “Where’s Dave? Hey! We left behind one of our party. We’re separated now. Isn’t he going to ride?” Brower had stayed on shore. We were now forty feet out. “Well, I swear, I swear, I swear,” Dominy continued, slowly. “He isn’t coming with us.” The Upset Rapid drew us in.

With a deep shudder, we dropped into a percentage of the hole—God only knows if it was ten—and the raft folded almost in two.

As we emerged on the far side, Dominy was still talking about “the great outdoorsman” who was “standing safely on dry land wearing a God-damned life jacket.” Abandoning my supposedly detached role in all this, I urged Dominy not to say anything when Dave, having walked around the rapid, rejoined us. Dominy said, “Christ, I wouldn’t think of it. I wouldn’t dream of it. What did he do during the war?” Brower was waiting for us when we touched the riverbank in quiet water.

Dominy said, “Dave, why didn’t you ride through the rapid?”

Brower said, “Because I’m chicken.”

That was the end of “Upset Rapid,” and it was followed in the printed story by a half-inch or so of white space. After the white space, this:

A Climber’s Guide to the High Sierra (Sierra Club, 1954) lists thirty-three peaks in the Sierra Nevada that were first ascended by David Brower. “Arrowhead. First ascent September 5, 1937, by David R. Brower and Richard M. Leonard.… Glacier Point. First ascent May 28, 1939, by Raffi Bedayn, David R. Brower, and Richard M. Leonard.…”

The new section went on to describe Brower as a rope-and-piton climber of the first order, who had clung by his fingernails to dizzying rock faces and granite crags. The white space that separated the Upset Rapid and the alpinist said things that I would much prefer to leave to the white space to say—violin phraseology about courage and lack of courage and how they can exist side by side in the human breast. In the juxtaposition of those two cards lay what made this phase of the writing process the most interesting to me, the most absorbing and exciting. Those two weeks on the picnic table notwithstanding, it has also always been the briefest. After putting the two cards together, and then constructing around them the rest of the book, all I had to do was write it, and that took more than a year.

* * *

Developing a structure is seldom that simple. Almost always there is considerable tension between chronology and theme, and chronology traditionally wins. The narrative wants to move from point to point through time, while topics that have arisen now and again across someone’s life cry out to be collected. They want to draw themselves together in a single body, in the way that salt does underground. But chronology usually dominates. On tablets in Babylonia, most pieces were written that way, and nearly all pieces are written that way now. After ten years of it at Time and The New Yorker, I felt both rutted and frustrated by always knuckling under to the sweep of chronology, and I longed for a thematically dominated structure.

In 1967, after spending a few weeks interviewing the art historian Thomas P. F. Hoving, who had recently been made director of the Metropolitan Museum, I found in going over my notes that his birth-to-present chronology was particularly unaccommodating to various themes. For example, he knew a whole lot about art forgery. As a teen-ager in New York, he came upon “Utrillos,” a “Boudin,” and a “Renoir” in a shop in the East Fifties, and sensed that they were fakes. Eight or ten years later, as a graduate student, he sensed wrong and was stung in Vienna by an art dealer selling “hot” canvases from “Budapest” during the Hungarian Revolution. Actually, they were forgeries turned out the previous day in Vienna. In later and wiser years, he could not help admiring Han van Meegeren, who created an entire fake early period for Vermeer. In the same manner, he admired Alfredo Fioravanti, who fooled the world with his Etruscan warriors, which were lined up in the Met’s Greek and Roman galleries until they were discovered to be forgeries. Most of all, he came to appreciate the wit of a talented crook who copied a silver censer and then put his tool marks on the original. At one point, Hoving studied the use of scientific instruments that help detect forgery. He even practiced forgery so he could learn to recognize it. All this having to do with the theme of forgery was scattered all over the chronology of his life. So what was I going to do to cover the theme of art and forgery? How was I going to handle, in this material, the many other examples of chronology versus theme? Same as always, chronology foremost? I threw up my hands and reversed direction. Specifically, I remembered a Sunday morning, when the museum was “dark” and I had walked with Hoving through its twilighted spaces, and we had lingered in a small room that contained perhaps two dozen portraits. A piece of writing about a single person could be presented as any number of discrete portraits, each distinct from the others and thematic in character, leaving the chronology of the subject’s life to look after itself.

Hoving had been, to put it mildly, an unpromising youth. For example, after slugging a teacher he had been expelled from Exeter. As a freshman at Princeton, his highest accomplishment was “flagrant neglect.” How did Peck’s rusticated youth ever become an art historian and the director of one of the world’s greatest museums? The structure’s two converging arms were designed to ask and answer that question. They meet in a section that consists of just two very long paragraphs. Paragraph 1 relates to the personal arm, Paragraph 2 relates to the professional arm, and Paragraph 2 answers the question. Or was meant to.

* * *

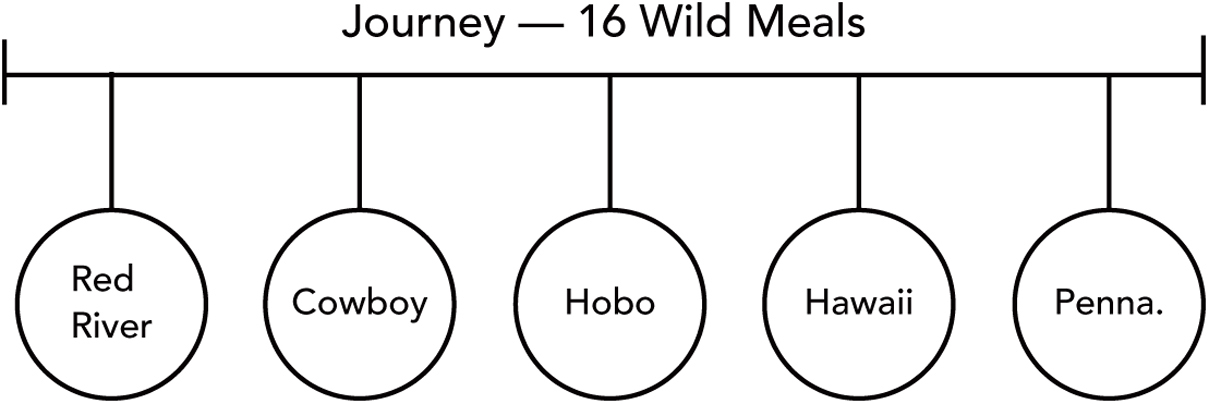

Other pieces from that era were variously chronological, none more so than this one, where the clock runs left to right in both the main time line and the set pieces hanging from it:

Written in 1968 and called “A Forager,” it was a profile of the wild-food expert Euell Gibbons, told against the background of a canoe-and-backpacking journey on the Susquehanna River and the Appalachian Trail.

* * *

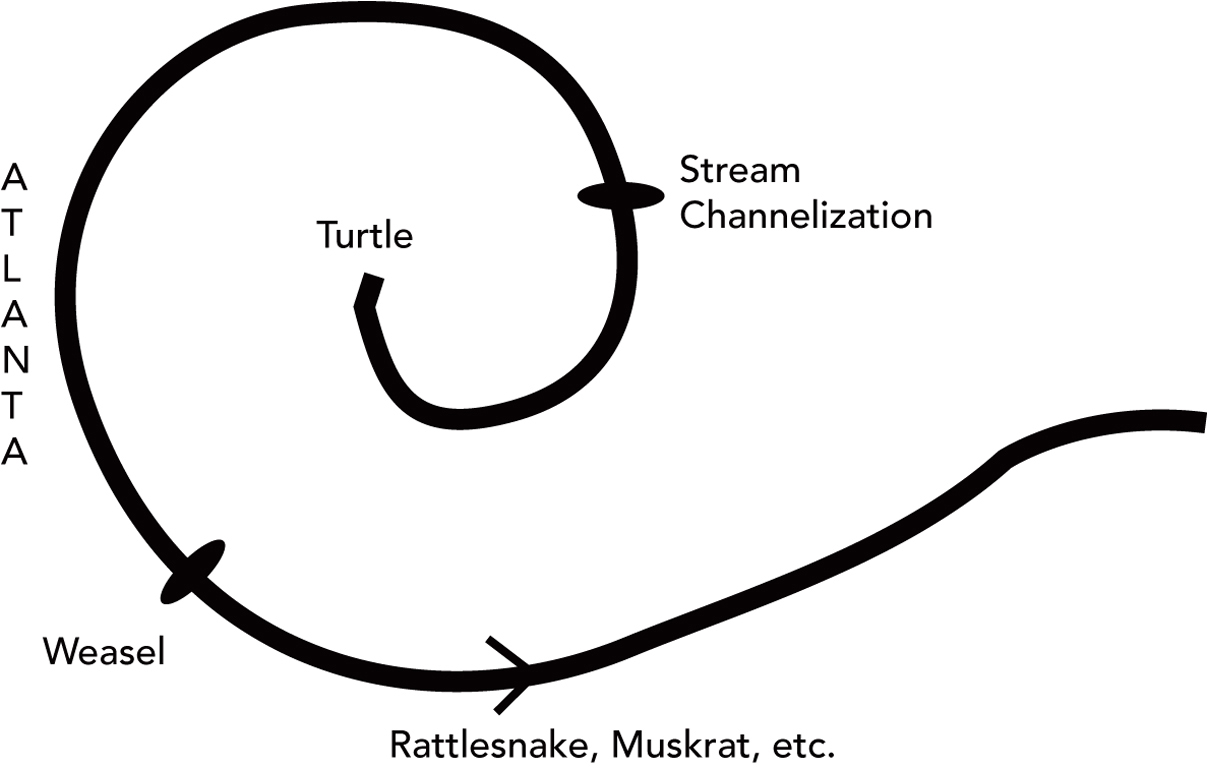

“Travels in Georgia” (1973) described an episodic journey of eleven hundred miles in the state, and the story would work best, I thought, if I started not on Day 1 but with a later scene involving a policeman and a snapping turtle:

So the piece flashed back to its beginnings and then ran forward and eventually past the turtle and on through the remaining occurrences. As a nonfiction writer, you could not change the facts of the chronology, but with verb tenses and other forms of clear guidance to the reader you were free to do a flashback if you thought one made sense in presenting the story.

* * *

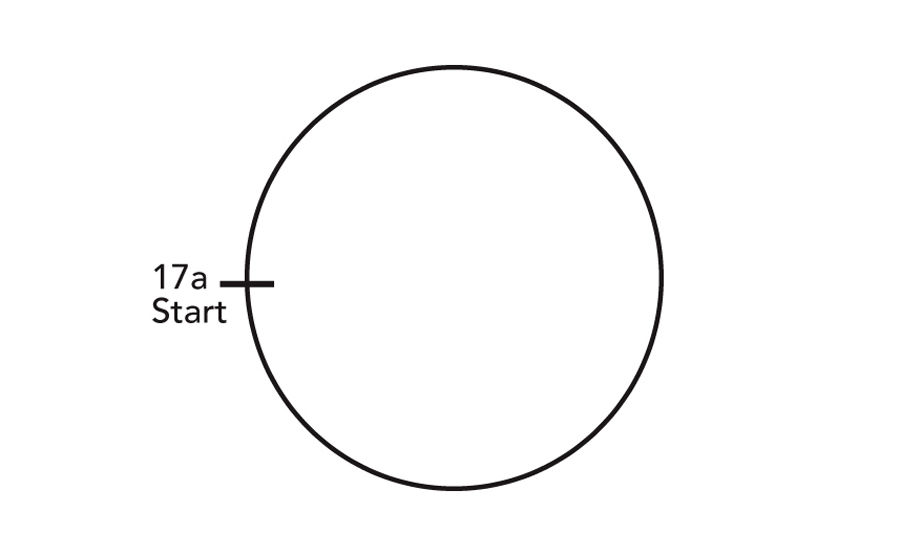

Here, in greater detail, is one more example from the nineteen-seventies, when I spent three years going back and forth to Alaska, summer and winter, on trips of as little as one month and as much as four. Three compositions resulted, each with its own structure. They were published in book form in 1977 as Coming into the Country. The first part—“The Encircled River”—described a canoe-and-kayak journey in Arctic Alaska, and I would like to go through its structure one component at a time. First this:

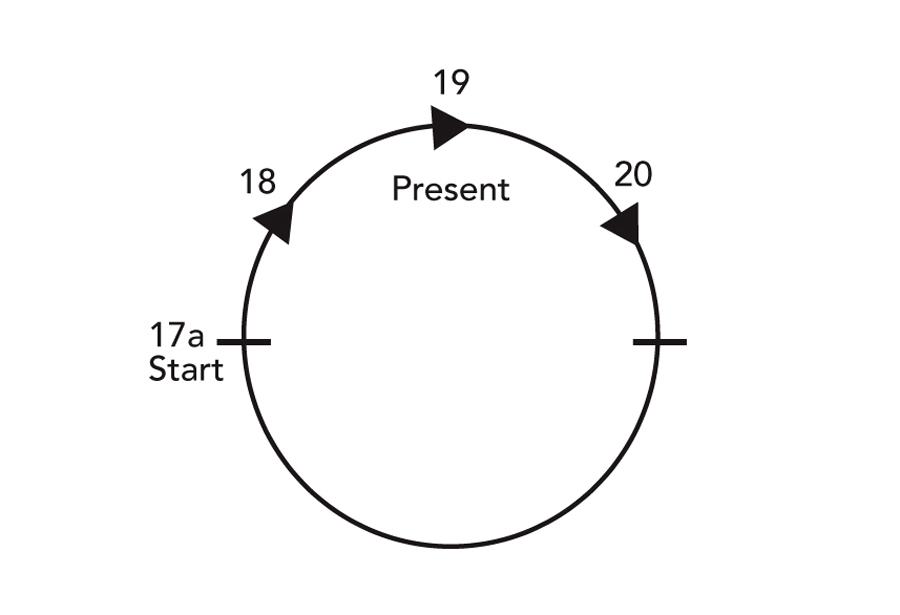

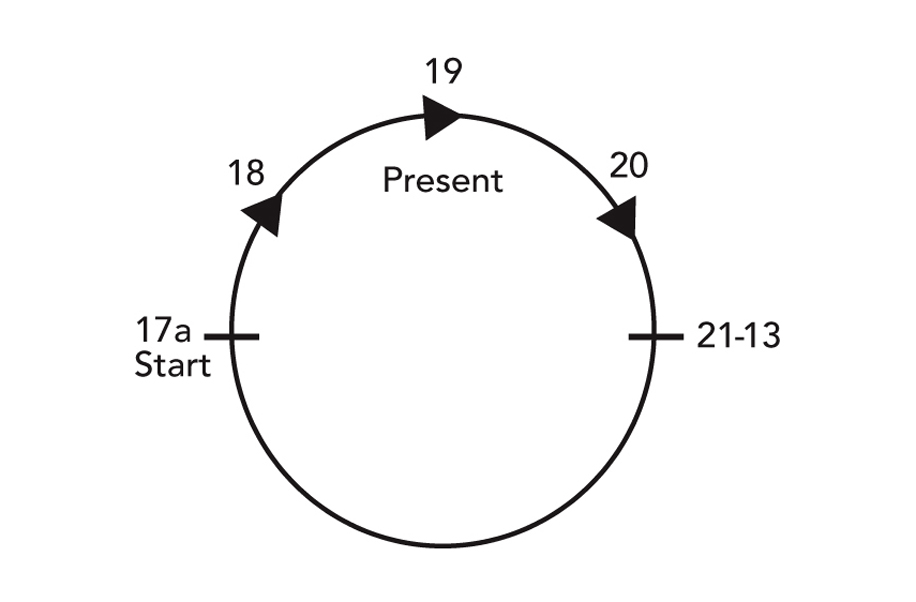

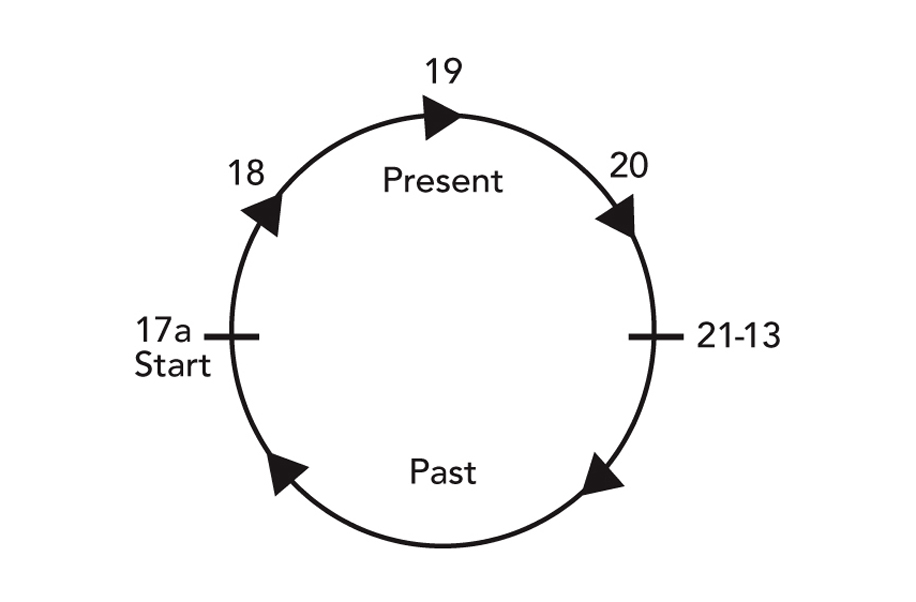

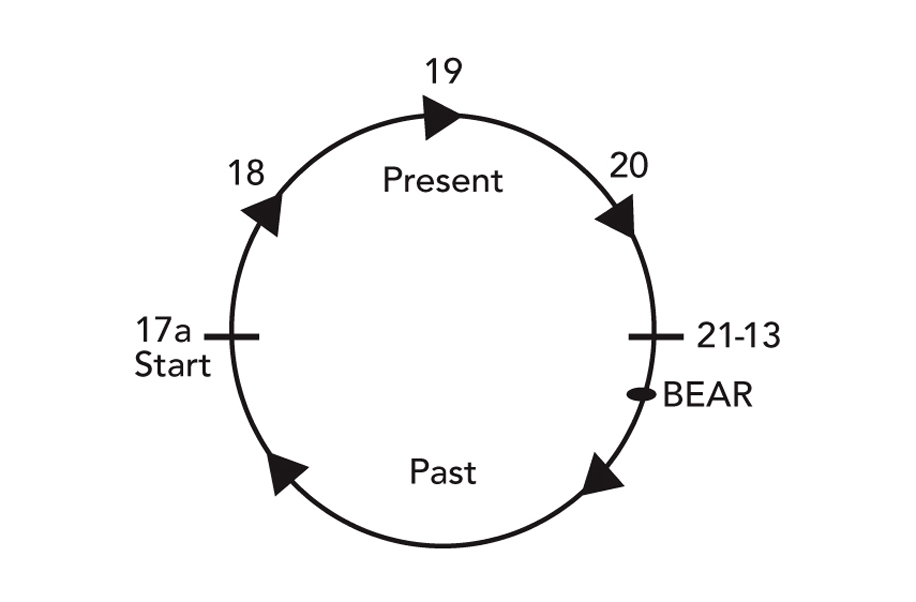

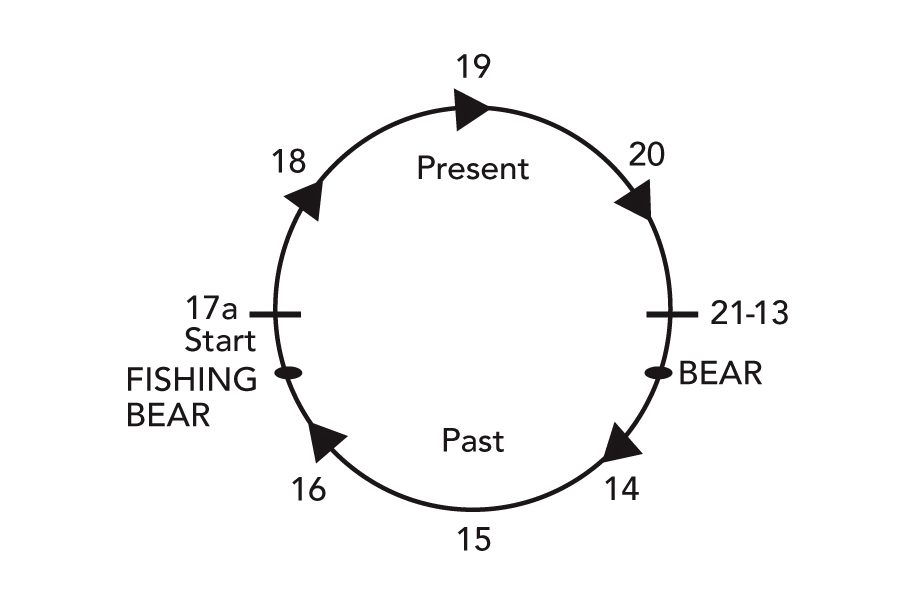

17a 18 19 20 21-13 14 15 16 17b

The numbers are calendar days. In northwest Alaska, that’s how many days it takes to paddle from the Brooks Range divide to Kiana.

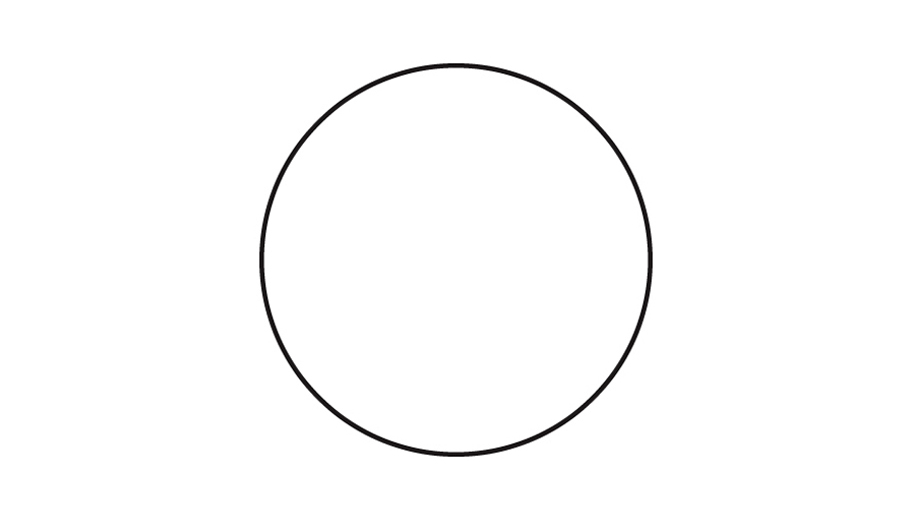

What impresses someone most of all about the Arctic world are its cycles. Meteorological cycles, biological cycles. Pendular swings in the populations of salmon, sheefish, caribou, lynx, snowshoe hare. Cycles unaffected by people. The wilderness operating in its own way. Seasonal cycles, annual cycles, cycles of five, ten, fifty, a hundred years. Cycles of the present and the past. This would obviously be an essential theme for a piece of writing about such terrain. We are dealing with a journey in a certain piece of time, and the piece of time can be something more than just a string of numbers. Possibly we can bend it and bring it upon itself, possibly find a structure—a structure that makes sense and is not just clever—that looks like this:

And start here, for good reason, on the fifth day of the journey, not the first.

There’s no throat clearing. You are right in the middle of things, and you choose the present tense for its immediacy.

You introduce the river and the five people on it with you and the arguments and themes of the piece, while you move the boats downstream. Suddenly the trip ends. What’s this? Well, the story doesn’t end, because the end of the trip is followed by a flashback.

Unlike most flashbacks, however, this one is going to stay back. It will almost complete the cycle, and that moment will be the end. The piece of writing has itself been a cycle—told in the present tense and then in the past.

On the first day of the journey, after being helicoptered with the boats to a point near the headwaters of the river, we all went off exploring on foot. Three of us made a fourteen-mile hike around a small mountain. After ten miles or so,

We passed first through stands of fireweed, and then over ground that was wine-red with the leaves of bearberries. There were curlewberries, too, which put a deep-purple stain on the hand. We kicked at some wolf scat, old as winter. It was woolly and white and filled with the hair of a snowshoe hare. Nearby was a rich inventory of caribou pellets and, in increasing quantity as we moved downhill, blueberries—an outspreading acreage of blueberries. Fedeler stopped walking. He touched my arm. He had in an instant become even more alert than he usually was, and obviously apprehensive. His gaze followed straight on down our intended course. What he saw there I saw now. It appeared to me to be a hill of fur. “Big boar grizzly,” Fedeler said in a near-whisper. The bear was about a hundred steps away, in the blueberries, grazing. The head was down, the hump high. The immensity of muscle seemed to vibrate slowly—to expand and contract, with the grazing. Not berries alone but whole bushes were going into the bear. He was big for a barren-ground grizzly. The brown bears of Arctic Alaska (or grizzlies; they are no longer thought to be different) do not grow to the size they will reach on more ample diets elsewhere. The barren-ground grizzly will rarely grow larger than six hundred pounds. “What if he got too close?” I said. Fedeler said, “We’d be in real trouble.” “You can’t outrun them,” Hession said. A grizzly, no slower than a racing horse, is about half again as fast as the fastest human being. Watching the great mound of weight in the blueberries, with a fifty-five-inch waist and a neck more than thirty inches around, I had difficulty imagining that he could move with such speed, but I believed it, and was without impulse to test the proposition.

That particular encounter occurred close to the start of the nine-day river trip. That bear would be, to say the least, a difficult act to follow. One dividend of this structure is that the grizzly encounter occurs about three-fifths of the way along, a natural place for a high moment in any dramatic structure.

And it also occurs just where and when it happened on the trip. You’re a nonfiction writer. You can’t move that bear around like a king’s pawn or a queen’s bishop. But you can, to an important and effective extent, arrange a structure that is completely faithful to fact.

On down the river we go.

All through the composition, the text in various ways reveals its absorption with the cyclic theme. An example near the beginning:

In the sixteenth century, the streams of eastern America ran clear (except in flood), but after people began taking the vegetation off the soil mantle and then leaving their fields fallow when crops were not there, rain carried the soil into the streams. The process continues, and when one looks at such streams today, in their seasonal varieties of chocolate, their distant past is—even to the imagination—completely lost. For this Alaskan river, on the other hand, the sixteenth century has not yet ended, nor the fifteenth, nor the fifth. The river flows, as it has since immemorial time, in balance with itself. The river and every rill that feeds it are in an unmodified natural state—opaque in flood, ordinarily clear, with levels that change within a closed cycle of the year and of the years. The river cycle is only one of many hundreds of cycles—biological, meteorological—that coincide and blend here in the absence of intruding artifice. Past to present, present reflecting past, the cycles compose this segment of the earth. It is not static, so it cannot be styled “pristine,” except in the special sense that while human beings have hunted, fished, and gathered wild food in this valley in small groups for centuries, they have not yet begun to change it.

And another, toward the end:

What had struck me most in the isolation of this wilderness was an abiding sense of paradox. In its raw, convincing emphasis on the irrelevance of the visitor, it was forcefully, importantly repellent. It was no less strongly attractive—with a beauty of nowhere else, composed in turning circles. If the wild land was indifferent, it gave a sense of difference. If at moments it was frightening, requiring an effort to put down the conflagrationary imagination, it also augmented the touch of life. This was not a dare with nature. This was nature.

And finally, at the end, just before the loop would close, we come upon another bear.

He was young, possibly four years old, and not much over four hundred pounds. He crossed the river. He studied the salmon in the riffle. He did not see, hear, or smell us. Our three boats were close together, and down the light current on the flat water we drifted toward the fishing bear.

He picked up a salmon, roughly ten pounds of fish, and, holding it with one paw, he began to whirl it around his head. Apparently, he was not hungry, and this was a form of play. He played sling-the-salmon. With his claws embedded near the tail, he whirled the salmon and then tossed it high, end over end. As it fell, he scooped it up and slung it around his head again, lariat salmon, and again he tossed it into the air. He caught it and heaved it high once more. The fish flopped to the ground. The bear turned away, bored. He began to move upstream by the edge of the river. Behind his big head his hump projected. His brown fur rippled like a field under wind. He kept coming. The breeze was behind him. He had not yet seen us. He was romping along at an easy walk. As he came closer to us, we drifted slowly toward him. The single Klepper, with John Kauffmann in it, moved up against a snagged stick and broke it off. The snap was light, but enough to stop the bear. Instantly, he was motionless and alert, remaining on his four feet and straining his eyes to see. We drifted on toward him. At last, we arrived in his focus. If we were looking at something we had rarely seen before, God help him so was he.

He seems to fit at the end, to provide a final scene, and the structure makes it work that way—although the encounter occurred in the exact middle of the trip.

Readers are not supposed to notice the structure. It is meant to be about as visible as someone’s bones. And I hope this structure illustrates what I take to be a basic criterion for all structures: they should not be imposed upon the material. They should arise from within it. That perfect circle was a help to me, but it could be a liability for anyone trying to impose such a thing on just any set of facts. A structure is not a cookie cutter. Certain Baroque poets, among others, wrote shaped verse, in which lines were composed so that the typography resembled the topic—blossoms, birds, butterflies. That also is not what I mean by structure. A piece of writing has to start somewhere, go somewhere, and sit down when it gets there. You do that by building what you hope is an unarguable structure. Beginning, middle, end. Aristotle, Page 1.

* * *

Each of those structures, from the nineteen-sixties and nineteen-seventies, was worked out after copying with a typewriter all notes from notebooks and transcribing the contents of microcassettes. I used an Underwood 5, which had once been a state-of-the-art office typewriter but by 1970 had been outclassed by the I.B.M. Selectric. With the cassettes, I used a Sanyo TRC5200 Memo-Scriber, which was activated with foot pedals, like a sewing machine or a pump organ. The note-typing could take many weeks, but it collected everything in one legible place, and it ran all the raw material in some concentration through the mind.

The notes from one to the next frequently had little in common. They jumped from topic to topic, and only in places were sequentially narrative. So I always rolled the platen and left blank space after each item to accommodate the scissors that were fundamental to my advanced methodology. After reading and rereading the typed notes and then developing the structure and then coding the notes accordingly in the margins and then photocopying the whole of it, I would go at the copied set with the scissors, cutting each sheet into slivers of varying size. If the structure had, say, thirty parts, the slivers would end up in thirty piles that would be put into thirty manila folders. One after another, in the course of writing, I would spill out the sets of slivers, arrange them ladderlike on a card table, and refer to them as I manipulated the Underwood. If this sounds mechanical, its effect was absolutely the reverse. If the contents of the seventh folder were before me, the contents of twenty-nine other folders were out of sight. Every organizational aspect was behind me. The procedure eliminated nearly all distraction and concentrated just the material I had to deal with in a given day or week. It painted me into a corner, yes, but in doing so it freed me to write.

Cumbersome aspects there may have been, but the scissors, the slivers, the manila folders, the three-by-five cards, and the Underwood 5 were my principal tools until 1984, a year in which I was writing about a schoolteacher in Wyoming and quoting frequently from a journal she began in 1905. Into several late drafts of that piece, I laboriously typed and retyped those journal entries—another adventure in tedium. Two friends in Princeton—Will Howarth, a professor of English, and Richard Preston, one of his newly minted Ph.D.s—had been waxing evangelical for months on end about their magical computers, which were then pretty much a novelty. Preston put me in touch with Howard J. Strauss, in Princeton’s Office of Information Technology. Howard had worked for NASA in Houston on the Apollo program and was now in Princeton guiding the innumerate. For a couple of decades, his contribution to my use of the computer in teaching, researching, and writing would be so extensive that—as I once wrote—if he were ever to leave Princeton I would pack up and follow him, even to Australia. When I met him in 1984, the first thing he said to me was “Tell me what you do.”

He listened to the whole process from pocket notebooks to coded slices of paper, then mentioned a text editor called Kedit, citing its exceptional capabilities in sorting. Kedit (pronounced “kay-edit”), a product of the Mansfield Software Group, is the only text editor I have ever used. I have never used a word processor. Kedit did not paginate, italicize, approve of spelling, or screw around with headers, wysiwygs, thesauruses, dictionaries, footnotes, or Sanskrit fonts. Instead, Howard wrote programs to run with Kedit in imitation of the way I had gone about things for two and a half decades.

He wrote Structur. He wrote Alpha. He wrote mini-macros galore. Structur lacked an “e” because in those days in the Kedit directory eight letters was the maximum he could use in naming a file. In one form or another, some of these things have come along since, but this was 1984 and the future stopped there. Howard, who died in 2005, was the polar opposite of Bill Gates—in outlook as well as income. Howard thought the computer should be adapted to the individual and not the other way around. One size fits one. The programs he wrote for me were molded like clay to my requirements—an appealing approach to anything called an editor.

Structur exploded my notes. It read the codes by which each note was given a destination or destinations (including the dustbin). It created and named as many new Kedit files as there were codes, and, of course, it preserved intact the original set. In my first I.B.M. computer, Structur took about four minutes to sift and separate fifty thousand words. My first computer cost five thousand dollars. I called it a five-thousand-dollar pair of scissors.

I wrote my way sequentially from Kedit file to Kedit file from the beginning to the end of the piece. Some of those files created by Structur could be quite long. So each one in turn needed sorting on its own, and sometimes fell into largish parts that needed even more sorting. In such phases, Structur would have been counterproductive. It would have multiplied the number of named files, choked the directory, and sent the writer back to the picnic table, and perhaps under it. So Howard wrote Alpha. Alpha implodes the notes it works on. It doesn’t create anything new. It reads codes and then churns a file internally, organizing it in segments in the order in which they are meant to contribute to the writing.

Alpha is the principal, workhorse program I run with Kedit. Used again and again on an ever-concentrating quantity of notes, it works like nesting utensils. It sorts the whole business at the outset, and then, as I go along, it sorts chapter material and subchapter material, and it not infrequently arranges the components of a single paragraph. It has completely served many pieces on its own. When I run it now, the action is instantaneous in a way that I—born in 1931—find breathtaking. It’s like a light switch. I click on “Run Alpha,” and in zero seconds a window appears that says, for example,

Alpha has completed 14 codes and 1301 paragraph segments were processed. 7246 lines were read and 7914 lines were written to the sorted file.

One line is 11.7 words.

Kedit’s All command helps me find all the times I use any word or phrase in a given piece, and tells me how many lines separate each use from the next. It’s sort of like a leaf blower. Mercilessly, it will go after fad words like “hone,” “pivot,” “proactive,” “icon,” “iconic,” “issues,” “awesome,” “aura,” “arguably,” and expressions like “reach out,” “went viral,” and “take it to the next level.” It suggests how much of “but” is too much “but.” But its principal targets are the legions of perfectly acceptable words that should not appear more than once in a piece of writing—“legions,” in the numerical sense, among them, and words like “expunges,” “circumvallate,” “horripilation,” “disjunct,” “defunct,” “amalgamate,” “ameliorate,” “defecate,” and a few thousand others. Of those that show up more than once, All expunges all.

When Keditw came along—Kedit for Windows—Howard rewrote everything, and the task was not a short one. In 2007, two years after he died, a long e-mail appeared in my in-box addressed to everyone on the “KEDIT for Windows Announcement list”—Subject: “News About Kedit.” It included this paragraph:

The last major release of KEDIT, KEDIT for Windows 1.5, came out in 1996, and we are no longer actively working on major “new feature” releases of the program. Sales have gradually slowed down over the years, and it now makes sense to gradually wind down.

It was signed “Mansfield Software Group, Storrs CT.”

This is when I began to get a true sense of the tensile strength and long dimension of the limb I was out on. I replied on the same day, asking the company how much time—after half a million words in twenty-three years—I could hope to continue using Kedit. In the back-and-forth that followed, there was much useful information, and this concluding remark:

If you run into any problems with KEDIT or with those macros in the future, let me know. You will definitely get my personal attention, if only because I’ll be the only one left at my company!

It was signed “Kevin Kearney.”

Driving to Boston one time, I stopped in at Storrs, home of the University of Connecticut, to meet him and show him some of the things Howard Strauss had done. In this Xanadu of basketball, I found Kearney and his wife, Sara, close to the campus in a totally kempt small red house previously occupied by a UConn basketball coach. From my perspective, they looked young enough and trim enough to be shooting hoops themselves, and that to me was especially reassuring. He was wearing running shoes, a Metropolitan Museum T-shirt. He had an alert look and manner; short, graying dark hair; a clear gaze, no hint of guile—an appealing, trusting guy.

Before long, Sara went off to an appointment, leaving us at the dining table with our laptops open like steamed clams. I was awestruck to learn that he had bought his first personal computer only two years before I had, and I was bemused to contemplate the utterly disparate vectors that had carried us to the point of sale—me out of a dark cave of pure ignorance and Kearney off a mainframe computer.

He grew up in New Haven and in nearby Madison, he told me, and at UConn majored in math, but he developed an even greater interest in computer science. In those pre-PC days, people shared time on the university’s mainframe—a system that was, in its way, ancestral cloud computing. Per student computer terminal, the university paid a hundred and fifty dollars a month, all caps. If the university wanted a terminal to do lowercase as well, the cost was thirty dollars higher. There were a lot of people then who thought computers were too expensive to do word processing.

The first UConn thesis ever written on a computer was done on the mainframe by a pharmacy major in 1976, when Kearney was a year past his own graduation and working in the university’s computer center (where he met Sara, from Maryland, an alumna of American University, and also a computer programmer). He still did not own a personal computer and could not afford a five-thousand-dollar pair of anything. Apple II had been on the market since 1977 but did not interest him. It was “too much of a toy”—its display was only forty characters wide. The displays on I.B.M. PCs were eighty characters wide. His father helped him buy one. Five thousand dollars in 1982 translates to nearly thirteen thousand dollars at this writing.

On the mainframe, everyone from undergraduates to programmers used an evolving variety of text editors, most notably Xedit, which was written at I.B.M. by Xavier de Lamberterie and made available in 1980. Kevin Kearney was so interested in Xedit that he bought forty manuals out of his own pocket and offered them to students and faculty. Then, after the new I.B.M. PCs appeared, and he had bought his first one, an idea he addressed was how to achieve mainframe power in a PC editor. “Xedit was in a different language that only worked on mainframes,” he told me. “Xedit was in mainframe assembler language, almost like machine language.” What was needed was a text editor that mainframe programmers could use on their PCs at home. As companies bought PCs for their employees—as insurance programmers, for example, went home to PCs at night—the need increased. So Kearney, aged twenty-eight, cloned Xedit to accomplish that purpose. Moreover, he said, “you could do some nifty additional things that didn’t exist on the mainframe. On the mainframe you couldn’t scroll. You couldn’t word-wrap to a new line.”

Writing the initial version of Kedit took him about four months, in late 1982. Like a newborn bear cub, it amounted to the first one per cent of what it would eventually become. “There are two kinds of editors,” Kearney continued. “One sees things as characters; Kedit sees it as a bunch of lines. It’s more primitive, in a sense, like keypunches. Each line is like one card.” He said he started with “some things from Xedit plus suggestions from others,” and his goal was “convenient text editing.” After a pause, he added, “I’d rather have Kedit be a good text editor than a bad word processor.” He asked me to take care not to create an impression that he invented much of anything. “What I did was package in a useful way a number of ideas. I.B.M. seemed happy enough with the cloning. There was no hint that they objected.”

Not remotely in the way, certainly, that Steve Jobs would object, in 1983, to what he characterized as Bill Gates’s theft of Apple’s mouse-driven Graphical User Interface. In an interface-to-interface encounter—described by Andy Hertzfeld, a Macintosh system designer who was present—Jobs shouted at Gates:

“You’re ripping us off! I trusted you, and now you’re stealing from us!” But Bill Gates just stood there coolly, looking Steve directly in the eye, before starting to speak in his squeaky voice. “Well, Steve, I think there’s more than one way of looking at it. I think it’s more like we both had this rich neighbor named Xerox and I broke into his house to steal the TV set and found out that you had already stolen it.”

Kevin Kearney—who, like Jobs and Gates and the prevailing demography of the digital world, was still under thirty—began putting Kedit ads in computer magazines, where ads were not expensive. Orders came in. “Mansfield Software Group” was headquartered in his apartment. He went to the campus bookstore, bought three-ring binders, and photocopied his instructions, thus making the original Kedit manual, which he sent to his customers with Kedit diskettes. At a conference in Boston in March, 1984, Kevin and Sara met Howard Strauss. Showing him Kedit, they were quickly taken aback. Howard waxed animatedly critical. Still set in his own mainframe mentality, he said, for example, “There’s no prefix area!” The prefix I.B.M. programmers were used to consisted of five equal-signs at the beginning of each line (=====). For technical reasons, they were useful in editing commands on mainframe terminals. But Kevin and Sara talked with Howard about much more, and he offered useful suggestions. A month or so later, Strauss telephoned Kearney for more talk, and the upshot was that Princeton bought Kedit’s first site license.

At the time, the Mansfield Software Group had a roster of one—one full-time entrepreneur. In the following year, the company moved into office space above a liquor store that was a kind of inholding on the UConn campus. For a decade or so across the late eighties and early nineties, it flourished, and the number of employees increased to as many as twelve. In 1987, a letter arrived from Barbara Tolejano, of Morgan Products Ltd., in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, who said that she had received in the mail her Kedit diskettes and manual, and had thrown “box, packing material, binder into outdoor trash container” because of “overwhelming garlic odor.” Mansfield’s expanding personnel liked garlicky sandwiches. The diskettes stank, too.

A version of Kedit called Kedit/Semitic was developed at Princeton in the nineteen-eighties. Its cursor popped up at the far right, and it wrote its way leftward in Hebrew and Arabic. I asked Kevin Kearney how many users, nationally and globally, Kedit has now. “Fewer than there used to be” is as close as he would come to telling me, but he said he still gets about ten e-mails a week asking for support.

“Are they essentially all from programmers, or are there other users in the e-gnorant zone like me?”

“Yes.”

Kedit did not catch on in a large way at Princeton. I used to know other Kedit users—a historian of science, a Jefferson scholar. Aware of this common software, we nodded conspiratorially. Today on the campus, the number of people using Kedit is roughly one. Not long ago, I asked Jay Barnes, an information technologist at Princeton, if he thought I was enfolded in a digital time warp. “Right; yes,” he said. “But you found it and it works, and you haven’t switched it because of fashion.” Or, as Tracy Kidder wrote in 1981, in The Soul of a New Machine, “Software that works is precious. Users don’t idly discard it.”

Kevin Kearney, who says he is “semi-retired,” hopes not “to see a bunch of orders showing up,” and he asked me to make clear that Kedit was “very much a thing of its time,” and its time is not today. I guess I’m living evidence of that.

* * *

When I would thank Howard Strauss for the programs he wrote and amplified and updated, he always said, “Oh, it was no trouble; there was nothing to it; it was all simple.”

For many years in my writing class, I drew structures on a blackboard with chalk. In the late nineteen-nineties, I fell off my bicycle, massively tore a rotator cuff, underwent surgery, spent months in physical therapy, and had to give up the chalk for alternative technologies. I was sixty-eight. Briefly, I worked things out with acetates and overhead projection. Enduringly, I was once again helped beyond measure by Howard Strauss.

With PowerPoint, he modernized my drawings of the structures of pieces written before I bought my first computer; and in 2005, during the last months of his life, he was still taking my rough sketches and turning them into structural presentations, some of them complicated and assisted by the use of color. Students in class would say things like “Wow, those PowerPoints are really good. How did you do that?” To which I responded, as I still do, “Oh, it was no trouble; there was nothing to it; it was all simple; Howard Strauss did it.”

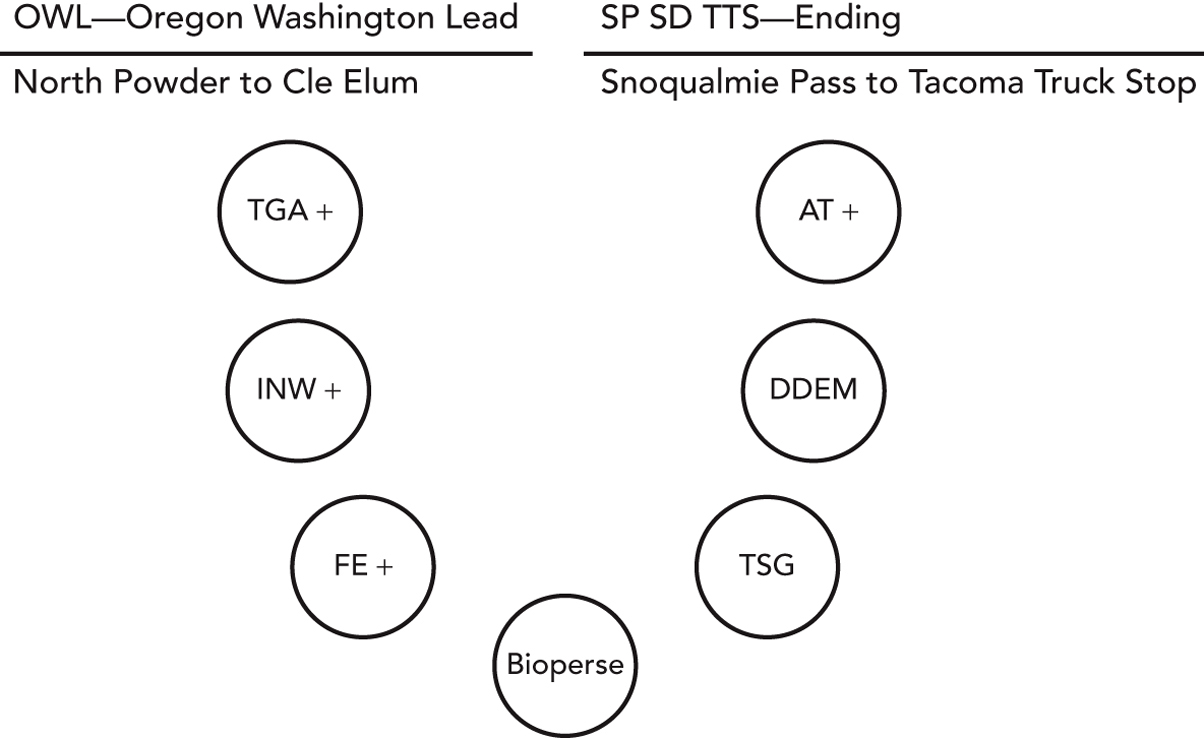

Showing in class the structural diagrams of “The Encircled River,” I used to recite, more or less, “It’s the story of a journey, and hence it represents a form of chronological structure, following that journey as it was made through space and time. There are structural alternatives, but for the story of a journey they can be unpromising and confusing when compared with a structure that is chronologically controlled.” Et cetera, et cetera, in an annual mantra about what I thought to be axiomatic: journeys demand chronological structures. That was before 2002, when I went from a truck stop in Georgia to a product delivery elsewhere in Georgia to an interior wash in South Carolina to a hazmat manufacturer in North Carolina and then across the country to the State of Washington in the sixty-five-foot chemical tanker owned and driven by a guy named Don Ainsworth.

Think about it. Think how it appeared to the writer when it was still a mass of notes. The story goes from the East Coast to the West Coast of the United States. Has any other writer ever done that? Has any other writer ever not done that? Even I had done something like it in discussing North American geology in Annals of the Former World. You don’t need to remember much past Meriwether Lewis, George R. Stewart, John Steinbeck, Bernard DeVoto, Wallace Stegner, and William Least Heat-Moon in order to discern a beaten path. If you are starting a westbound piece in, say, Savannah, can you get past Biloxi without caffeinating the prose? If Baltimore—who is going to care if you get through Cumberland Gap? New York? The Hackensack River. If you start in Boston, turn around. In a structural sense, I turned around—once again reversing a prejudice. In telling this story, the chronology of the trip would not only be awkward but would also be a liability.

Ainsworth and I started in Bankhead, Georgia, where I met him, after our five years of correspondence. When I got out of his truck in Tacoma, I had ridden three thousand one hundred and ninety miles with him.

Just the fact of those three thousand one hundred and ninety miles, if mentioned in the past tense early in the piece, might open the way to a thematic structure. The lead should be somewhere on the road in the West. The reader would see the span of the journey, the general itinerary. Thematic details could coalesce in varying categories and from all over the map in the form of set pieces on truck stops, fuel economy, driver demographics, Ainsworth’s idiosyncrasies, and other topics. Where to start?

In the State of Wyoming are four thousand square miles called the Great Divide Basin, where the Continental Divide itself divides, like separating strands of old rope, surrounding a vast landscape that does not drain to the Atlantic or the Pacific. We went right through it in the chemical tanker, and I thought it might be an oddly interesting place in which to begin.

The lead would be chronological (rolling westward), and after the random collection of themes the final segment would pick up where the first one left off and roll on through the last miles to the destination. Thus two chronological drawstrings—one at the beginning of the piece, the other at the end—would pull tight the sackful of themes.

Good idea, but I scrapped the Great Divide Basin. It was too far east. There was too much stuff from Idaho, Oregon, and so forth that ought best to be in the thematic groupings. So, to tell of this trip from coast to coast—after establishing my own credentials with a personal preamble in the New Jersey bad-driver clinic—I started in eastern Oregon with Deadman Pass and Cabbage Hill and Ainsworth saluting a girl in a bikini.

From Atlanta and Charlotte to North Powder, Oregon, this was the first time that Ainsworth had so much as tapped his air horn. In the three thousand one hundred and ninety miles I rode with him he used it four times.

Of the seven thematic sections that followed, each, in concept, would be much like the section I coded TSG.

If there is one indispensable theme about the big behemoth trucks, it is the nature and description of truck stops generally. The principal truck stops described in the piece (and dotted here) would be in places like Kingdom City, Missouri; Bankhead, Georgia; Oak Grove, Kentucky; and Little America, Wyoming.

Explosives are carried in liquid form in tankers. The more prudent truck stops have designated “safe havens”—Class 1 parking spaces situated, if not in the next county, at least, as Ainsworth put it, “a little away from the rest of the folks who may not want to be there when the thing lights off.”

…

I think it can be said, generally, that truckers are big, amiable, soft-spoken, obese guys. The bellies they carry are in the conversation with hot-air balloons. There are drivers who keep bicycles on their trucks, but they are about as common as owner-operators of stainless-steel chemical tankers.

In recapitulation, the structure of the story was this:

* * *

Often, after you have reviewed your notes many times and thought through your material, it is difficult to frame much of a structure until you write a lead. You wade around in your notes, getting nowhere. You don’t see a pattern. You don’t know what to do. So stop everything. Stop looking at the notes. Hunt through your mind for a good beginning. Then write it. Write a lead. If the whole piece is not to be a long one, you may plunge right on and out the other side and have a finished draft before you know it; but if the piece is to have some combination of substance, complexity, and structural juxtaposition that pays dividends, you might begin with that acceptable and workable lead and then be able to sit back with the lead in hand and think about where you are going and how you plan to get there. Writing a successful lead, in other words, can illuminate the structure problem for you and cause you to see the piece whole—to see it conceptually, in various parts, to which you then assign your materials. You find your lead, you build your structure, you are now free to write.

Some of these thoughts on leads, taken from my seminar notes, were printed several years ago in the Word Craft column of The Wall Street Journal. In slightly altered form, I’m including them here. I would go so far as to suggest that you should always write your lead (redoing it and polishing it until you are satisfied that it will serve) before you go at the big pile of raw material and sort it into a structure.

O.K. then, what is a lead? For one thing, the lead is the hardest part of a story to write. And it is not impossible to write a very bad one. Here is an egregiously bad one from an article on chronic sleeplessness. It began: “Insomnia is the triumph of mind over mattress.” Why is that bad? It’s not bad at all if you want to be a slapstick comedian—if humor, at that stratum, is your purpose. If you are serious about the subject, you might seem to be indicating at the outset that you don’t have confidence in your material so you are trying to make up for it by waxing cute.

I have often heard writers say that if you have written your lead you have in a sense written half of your story. Finding a good lead can require that much time, anyway—through trial and error. You can start almost anywhere. Several possibilities will occur to you. Which one are you going to choose? It is easier to say what not to choose. A lead should not be cheap, flashy, meretricious, blaring. After a tremendous fanfare of verbal trumpets, a mouse comes out of a hole blinking.

Blind leads—wherein you withhold the name of the person you are writing about and reveal it after a paragraph or two—range from slightly cheap to very cheap. Don’t be concerned if you have written blind leads. I’ve written my share of blind leads, I can tell you. There’s nothing inherently wrong with them. They’re so obvious, though. You should ration such indulgences through time. A blind lead is like a magician pulling a rabbit out of a hat, but the ears were sticking up from the get-go. Be conscious of the risk—of what is often wrong with such things—and then go ahead and try them. In this or that piece of mine, I have felt that a blind lead was by far the best choice. But not very often.

All leads—of every variety—should be sound. They should never promise what does not follow. You read an exciting action lead about a car chase up a narrow street. Then the article turns out to be a financial analysis of debt structures in private universities. You’ve been had. The lead—like the title—should be a flashlight that shines down into the story. A lead is a promise. It promises that the piece of writing is going to be like this. If it is not going to be so, don’t use the lead. Some leads are much longer than others. I am not talking just about first sentences. I am talking about an integral beginning that sets a scene and implies the dimensions of the story. That might be a few words, a few hundred words. And it might be two thousand words, setting the scene for a story fifty times as long. A lead is good not because it dances, fires cannons, or whistles like a train but because it is absolute to what follows.

Another way to prime the pump is to write by hand. Keep a legal pad, or something like one, and when you are stuck dead at any time—blocked to paralysis by an inability to set one word upon another—get away from the computer, lie down somewhere with pencil and pad, and think it over. This can do wonders at any point in a piece and is especially helpful when you have written nothing at all. Sooner or later something comes to you. Without getting up, you roll over and scribble on the pad. Go on scribbling as long as the words develop. Then get up and copy what you have written into your computer file.

What counts is a finished piece, and how you get there is idiosyncratic. Alternating between handwriting and computer typing almost always moves me along, but that doesn’t mean it will work for you. It just might. I knew an editor who had a lot of contempt for nearly all writers and did his own writing with a quill pen. No one approaches this topic in quite the way that Anne Tyler does, just as no one without a photocopying machine could come near Saint Maybe, The Accidental Tourist, Breathing Lessons, or Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant. “I have all kinds of superstitions about writing,” she told the Authors Guild Bulletin. “When I’m working on a book, I write five days a week, but never on weekends or any legal holidays; I use a Parker 75 fountain pen with a nib marked 62 which, to my horror, I’ve discovered they no longer make, and black ink and unlined white paper; and I rewrite each draft in longhand all over again even though I’ll have typed the earlier drafts into the computer, because to me writing feels like a kind of handicraft. It feels as if I’m knitting a novel.”

In 1987, Wendell Berry wrote an essay called “Why I Am Not Going to Buy a Computer.” He explained: “As a farmer, I do almost all of my work with horses. As a writer, I work with a pencil or a pen and a piece of paper.… I would hate to think that my work as a writer could not be done without a direct dependence on strip-mined coal.… For the same reason, it matters to me that my writing is done in the daytime, without electric light.”

Teaching Son of the Morning Star one year, I was full of admiration for the way Evan S. Connell would briefly mention something, amplify it slightly fifteen pages later, and add to it twenty pages after that, gradually teasing up enough curiosity to call for a full-scale set piece. This especially applied to the war chief Gall, who spoke a few arresting words in his first appearance, more words that were even more interesting in his second cameo, and so on through a couple of hundred pages. This is nonfiction and these were researched quotations. Your interest in and curiosity about Chief Gall and his heroic intelligence gradually builds to a point where you are ready to choke the author for not telling you more. At that point, Evan S. Connell rolls out a fine and detailed biographical portrait of the great Hunkpapa Lakota.

I wanted to cite in class each mention of Gall from Page 1 to the portrait. Son of the Morning Star has a very brief, very bad index. So I wrote to Evan Connell, whom I had never met, asking him to save me lots of time and do me the great favor of searching the text in his computer for all mentions of Gall, a task that surely would not take more than a few moments. Computer? he wrote back. Computer? His technology had not risen past his portable Olivetti.

That was at the end of the twentieth century. In 2011, Lilith Wood, a former student of mine, wrote to tell me that she was writing a book about her native Alaska and had challenged her computer with a typewriter—“a 1970-something Remington Premier, bought online from a shop in Portland called Blue Moon Camera and Machine.” She went on to say, “The process was very personalized, and included phone conversations with the shop’s owner. On the Web site they asked ‘Are you ready to have a lasting relationship with a machine?’ I really enjoy that there’s no on/off switch. Oh, and it has just been so pleasurable to type on it. I put on music and really get going. I use it at a standing desk, and I really have to punch those keys.”

* * *

In 2003, I was hoping to find a way to ride on a river towboat as part of a series of pieces on freight transportation. I had reason not to be optimistic. Corporations prepare for journalists with bug spray. They are generally less approachable than, say, the F.B.I., and, if at all agreeable, take even more precautions. I had been rebuffed flatly by various companies and jilted by some that at first said yes. Vice-presidents said yes. CEOs heard about it and said no.

Vice-president: But Adolf, this guy is fangless. He’s not Seymour Hersh. He’s not Upton Sinclair.

Adolf: I don’t care who he is. He’s a journalist, and no matter what they write no journalist is ever going to do our company any kind of good.

Against that background, and some days after writing a letter of request, I called Memco Barge Line, in St. Louis, and asked for Don Huffman. He said, “What day would you like to go?”

It was as if I were talking to Southwest Airlines. Tows are moving about the country all the time. When and where would I like to get on one? I flew to St. Louis, and went up to Grafton, where the Billy Joe Boling came along after a while and picked me off the riverbank with a powered skiff.

The river was the Illinois—barge route from the Mississippi to the outskirts of Chicago. At Grafton, in southern Illinois, the Billy Joe Boling collected its fifteen barges from larger tows in the Mississippi, wired them taut as an integral vessel, and went up the Illinois until constricting dimensions of the river forced another exchange, with a smaller towboat, and the Billy Joe Boling took a new rig of fifteen barges downstream. This endless yo-yo was not exactly a journey in the Amundsen sense. There was no vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an end. If ever there was a journey piece in which a chronological structure was pointless, this was it. In fact, a chronological structure would be misleading. Things happened, that’s all—anywhere and everywhere. And they happened in themes, each of which could have its own title at the head of a section, chronology ignored.

The over-all title was “Tight-Assed River.” There were eight sections. One section’s title was “Calling Traffic.”

The arrows coincide with places where things happened, such as Creve Coeur Landing, Kickapoo Bend. But they are not consecutive in the story.

When I told my friend Andy Chase that I was coming out here, he said, “The way they handle those boats—gad! They go outrageous places with them. The ship handling is phenomenal.” The fact notwithstanding that Andy is a licensed master of ships of any gross tons upon oceans, he said he would envy me being here. This tow is not altogether like an oceangoing ship. We are a lot longer than the Titanic, yes, but we are a good deal lighter. We weigh only thirty thousand tons. Yet that is surely enough to make our slow motion massive, momentous, tectonic. Fighting the current with full left rudder and full left flanking rudder in the eighty-degree turn at Creve Coeur Landing, Kickapoo Bend, Tom Armstrong says, “I’m trying to get it pointed up before it puts me on the bank. There’s no room for maneuvering. You can’t win for losing. You just don’t turn that fast. You just don’t stop that fast. Sometimes we don’t make our turns. We have to back up. The Illinois River’s such a tight-assed river.”

…

Trains run under centralized systems. These people are self-organized, talking back and forth on VHF, planning hold-ups and advances, and signing off with the names of their vessels: “Billy Joe Boling southbound, heading into Anderson Lake country. Billy Joe Boling, southbound.”

This is known as “calling traffic.”

…

Tom calls to another captain, “You’d better give them a shout down there before you get committed.” In other words, before you proceed you need to know that the river is open to—and including—your next manageable hold-up spot. St. Louis to Chicago, Chicago to St. Louis, this is like jumping from lily pad to lily pad.

…

When two moving tows, in adequate water, are passing, the captains say to each other, “See you on the 1,” or “See you on the 2.” Passing on the 1 always means that both boats would turn to starboard to avoid collision. Two boats, meeting and passing on the 1, will go by each other port to port. Therefore, passing on the 1 in opposite directions is different from passing on the 1 when overtaking. Passing on the 1 when overtaking is to go by the other boat’s starboard side. The stand-on vessel, nearly always a vessel heading upstream, maintains everything as is. The action vessel maneuvers. If you are learning this on the job, you may by now be up a street in Peoria.

* * *

Another mantra, which I still write in chalk on the blackboard, is “A Thousand Details Add Up to One Impression.” It’s actually a quote from Cary Grant. Its implication is that few (if any) details are individually essential, while the details collectively are absolutely essential.

What to include, what to leave out. Those thoughts are with you from the start. While scribbling your notes in the field, you obviously leave out a great deal of what you’re looking at. Writing is selection, and the selection starts right there at Square 1. When I am making notes, I throw in a whole lot of things indiscriminately, much more than I’ll ever use, but even so I am selecting. Later, in the writing itself, things get down to the narrowed choices. It’s an utterly subjective situation. I include what interests me and exclude what doesn’t interest me. That may be a crude tool but it’s the only one I have. Broadly speaking, the word “interests” in this context has subdivisions of appeal, among them the ways in which the choices help to set the scene, the ways in which the choices suggest some undercurrent about the people or places being described, and, not least, the sheer sound of the words that bring forth the detail. It is of course possible to choose too much costume jewelry and diminish the description, the fact notwithstanding that, by definition in nonfiction writing, all the chosen items were of course observed.

If art is where you find it, you can find it in a remark by Cary Grant and you can find it in the strategy of Earl Blaik, the first college football coach to hire Vince Lombardi. Blaik coached at the U.S. Military Academy in an era when Army teams were undefeated. He amassed data from films (as everyone, of course, does now), and in those days films were made of actual film called celluloid. After being exposed, it had to be processed in a lab. West Point is fifty-five miles up the Hudson. The nearest lab was in Brooklyn. David Maraniss tells this story in When Pride Still Mattered: A Life of Vince Lombardi (Simon & Schuster, 1999, p. 107). Blaik sent the apprenticed Lombardi to Brooklyn to deliver Army football films and wait for them to be developed. Then, each week, his orders were to hurry back to West Point but only after stopping in Manhattan at the Waldorf-Astoria Towers and showing the football games to General Douglas MacArthur. The movies provided only a small percentage of the data Blaik routinely collected before preparing to face the next enemy. Maraniss:

Blaik’s signature talent was using all this data to create something clean and simple. He had what Lombardi called “the great knack” of knowing what offensive plan to use against what defense and then “discarding the immaterial and going with the strength.” All the detailed preparations resulted not in a mass of confusing statistics and plans, but in the opposite, paring away the extraneous, reducing and refining until all that was left was what was needed for that game against that team. It was a lesson Lombardi never forgot.…

Possibly I could have used some coaching when I structured Looking for a Ship. But it wouldn’t have altered the result:

This was the weirdest ever, and in no way could serve as even a faint suggestion of what an ideal structure should be—that is, simple, straightforward, invisible. Despite its cuneiform appearance, though, it functioned in a generally hidden manner, but letters from readers did show up: “What happened after the ending?” “Did the ship ever make it to port?” “What happened to the stowaways?” And so forth. The fact that all such questions were answered in the text is not flattering to the attention attracted by the text.

In the beginning as well as the ending, I wanted to have my cake and eat it too. I wanted the story of the voyage to begin in total darkness on the ship’s bridge at 4 a.m. in the southeast Pacific Ocean off Valparaiso, and to be given the immediacy of the present tense. As dawn began, the light would gradually reveal the appearance of the people who were talking. I also wanted to make clear at the outset the fact that my presence on that particular ship was the result of an essentially anonymous and absolutely random turn of union-hall chance, and to do that I needed to describe where I had travelled with a Second Mate who was looking for a ship. In a late part of the voyage—northbound, about a hundred miles offshore and approaching the Gulf of Panama—the ship went dead in the water. It wallowed in the swells. Two black balls were soon hoisted on the halyards of the uppermost mast—the universal statement “Not Under Command.” This being a book whose deepest theme was the fading out and approaching doom of the U.S. Merchant Marine, I looked upon the engines’ failure as a gift. I wanted the story to end with the ship lightly creaking, under the black balls, dead in the water.

This was 1988 and the structure was under total chronological control. It would be if I were writing it now. It began and ended with flashbacks. The cinematic present-tense lead on the dark bridge in Chilean waters was preceded by a past-tense account of how we came to be on that ship. To cover the points and events that came after the failure of the engines—the discovery of the stowaways in Balboa, dodging a tropical storm in the Caribbean, the discovery in Port Newark of a crack in the hull, visiting the captain at his home in Jacksonville and others of the crew in various cities—I had to think up ways to fix a block of time in the future.

Six years earlier, I was walking around in the Alps with a four-man patrol of Swiss soldiers. We had been together three weeks and were plenty compatible. Straying off-limits, not for the first time, we went into a restaurant called Restaurant. Military exercises were going on involving mortars and artillery up and down the Rhone Valley, above which the cantilevered Restaurant was fourteen hundred feet high. The soldiers had a two-way radio with which to receive orders, be given information, or report intelligence to the command post. They stirred their fondue with its antenna. They sent coded messages to the command post: “A PEASANT IN OBERWALD HAS SEEN FOUR ARMORED CARS COMING OUT OF ST. NIKLAUS AND HEADING FOR THE VALLEY.” More fondue, then this: “TWO COMPANIES OF ENEMY MOTORIZED FUSILIERS HAVE REACHED RARON. ABOUT FIFTEEN ARMORED VEHICLES HAVE BEEN DESTROYED.” And later this: “AN ATOMIC BOMB OF PETITE SIZE HAS BEEN DROPPED ON SIERRE. OUR BARRICADES AT VISP STILL HOLD. THE BRIDGES OF GRENGIOLS ARE SECURE. WE ARE IN CONTACT WITH THE ENEMY.”

Setting down a pencil and returning to the fondue, I said to myself, “There is my ending.” Like the failed engines on the ocean, the petite A-bomb was a gift to structure. Ending pieces is difficult, and usable endings are difficult to come by. It’s nice when they just appear in appropriate places and times.

After the tow rig ran aground, the river pilot Mel Adams said, “When you write all this down, my name is Tom Armstrong.”

I always know where I intend to end before I have much begun to write. William Shawn once told me that my pieces were a little strange because they seemed to have three or four endings. That surely is a result of preoccupation with structure. In any case, it may have led to an experience I have sometimes had in the struggle for satisfaction at the end. Look back upstream. If you have come to your planned ending and it doesn’t seem to be working, run your eye up the page and the page before that. You may see that your best ending is somewhere in there, that you were finished before you thought you were.

People often ask how I know when I’m done—not just when I’ve come to the end, but in all the drafts and revisions and substitutions of one word for another how do I know there is no more to do? When am I done? I just know. I’m lucky that way. What I know is that I can’t do any better; someone else might do better, but that’s all I can do; so I call it done.