John – lead

vocals, acoustic guitar, possibly lead guitar

Paul – harmony and backing vocals, bass

George – harmony and backing vocals, lead guitar

Ringo – drums

‘Nowhere Man’, like ‘In My Life’, was a song that came from out of the blue. In this case, John had been trying to write a song for the new album for several hours, when he gave up in frustration. As soon as he stopped trying, inspiration came. “Then I thought of myself as Nowhere Man – sitting in his nowhere land.” At which point the song “came out in one gulp”.

Compared with the previous four or five years, 1965 was relatively quiet for the Beatles. Until work began on Rubber Soul, the group’s main projects had been to produce the film and album of Help!, and two fortnight-long tours of Europe and America. There were also a number of other smaller engagements, such as press interviews over their MBEs, and the publication of John’s second book, A Spaniard In The Works, but over the course of the year they had had over four months’ free time. For John, this was the beginning of the period captured by Maureen Cleave’s piece ‘How does a Beatle live? John Lennon lives like this’. This was the more-popular-than-Jesus article of the following spring that caused so much trouble on their American tour. “Their existence is secluded and curiously timeless. ‘What day is it?’ John Lennon asks with interest when you ring up with news from outside … He can sleep almost indefinitely, is probably the laziest person in England.” An impression of the hours whiled away at Kenwood, the 27-room mock-Tudor home that had been home to the Lennons since July 1964, can be gained from ‘Nowhere Man’, John’s first song of social, rather than inter-personal relevance. He’s sitting in his mansion, impotently making plans, not knowing where he’s going. “There’s something else I’m going to do, something I must do – only I don’t know what it is,” he told Maureen Cleave.

Ray Coleman, in an interview with John at Weybridge around this time, also commented on John’s morose attitude. “His restlessness was evident as he took me up to the music room where, amid countless tapes, recorders, amplifiers, and a mess of paper, he was strumming his guitar and writing a song which turned out later as ‘Nowhere Man’.”

The structure and arrangement of ‘Nowhere Man’ initially disguise the aim of the song. At first it seems to anticipate Paul’s ‘The Fool On The Hill’, mocking someone who doesn’t know his own mind, who has to wait to be told what to think. As with Paul’s song, a closer look reveals another truth. It becomes clear that in ‘Nowhere Man’ John is targeting himself – as Paul points out, “He treated it as a third-person song, but he was clever enough to say, ‘Isn’t he a bit like you and me?’ ‘Me’ being the final word.” Although the protagonist recognises his potential – “the world is at your command” – he is bound by his own hopeless captivity, and is unable to act to realise his full ability. Unlike the Fool, this man is harmless (“As blind as he can be”), but bigoted (“Just sees what he wants to see”). The repeated “The world is at your command” even offers some ‘Hey Jude’ go-out-and-get-her type encouragement, but you cannot help feeling that whereas Jude may succeed, Nowhere Man will not.

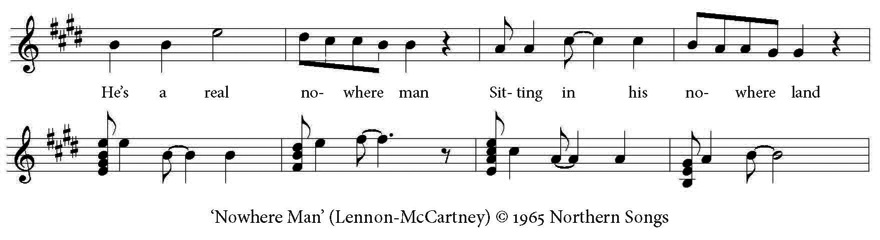

The song begins with tight a cappella three-part block harmonies, an introduction for an up-tempo song that had not been used before, although would be tried again with ‘Paperback Writer’.

After four bars the instruments tumble in, led by the acoustic guitar. The verse is based on what Wilfrid Mellers calls the “hymnbook diatonicism” of E–B–A–E (I–V–IV–I), but with the resolution coming through F#m7–Am (ii7–iv) on “Making all his nowhere plans …”, an interesting minor third interval.

The middle eight revolves around G#m–A (iii–IV), but resolving with F#m7 (held for the two bars of “The world is at your command”) and B7 (ii7–V7) the last time around.

The guitar fills within the verses, played by George on his Fender Stratocaster (with a maple neck and rosewood fret-board, no less) are arresting, but restrained. For example, for the first fill, after the second line, he plays an ascending Bm/E chord, then moves down against the direction to leave us back where we started, waiting for someone to lend us a hand. The fine solo in the middle eight provides a mirror image of the verse, rising when the melody goes down and vice versa, held within the harmonic structure.

The guitar is heavily compressed with an immense amount of treble, so that it rings out throughout the song, although this is most prominent during the solo. As Paul told Mark Lewisohn –

“I remember we wanted very treble-y guitars, which they are, they’re among the most treble-y guitars I’ve ever heard on record. The engineer said ‘All right, I’ll put full treble on it’ and we said ‘That’s not enough’ and he said ‘But that’s all I’ve got, I’ve only got one pot and that’s it!’ and we replied ‘Well, put that through another lot of faders and put full treble up on that. And if that’s not enough we’ll go through another lot of faders and …’”

The brightness is accentuated by one of the microphones teetering on the brink of feedback, noticeable after the first “what you’re missing” (although this was later cleaned up, for the Yellow Submarine Songtrack CD, for example). Because of the exaggerated brilliance, the deft harmonic “ping” at the end of the middle eight is expected and a nice touch to round off the solo.

It’s likely that two guitars are at play here, and either John and George are duetting, or George is double-tracked and then internally mixed onto a single track of the tape.

The backing vocals provide a link with the previous song, in their “ah, la-la-la” simplicity, but here they try to add to the sentiment of the song, rather than accentuate its dragging nature. The dreamer, constantly hustled and prodded with the vocals, weaving bass and inspired guitar would be addressed again by John in the future – from ‘I’m Only Sleeping’, through ‘Imagine’ and ‘#9 Dream’ to ‘Watching The Wheels’.

The group had made a first attempt at recording the song on 21 October, but John had realised that some extra work was needed. He evidently set about this immediately as they completed it the following day.

‘Nowhere Man’ was held off the American version of Rubber Soul and released as a single, backed with ‘What Goes On’, but only reached number three in March 1966. It also appeared on “Yesterday” … And Today, released the following June.

The song was also used in the film Yellow Submarine, in which the Dick Emery-voiced character of Jeremy Boob, despite being in the original Lee Minoff script, seems to have been introduced merely in order for ‘Nowhere Man’ to be sung to him.