John – lead

vocals, rhythm guitar

Paul – harmony vocals, bass, piano

George – harmony vocals, lead guitar

Ringo – drums, maracas

George Martin – harmonium

Providing a link between ‘Words Of Love’ and ‘All You Need Is Love’, ‘The Word’ is a rallying cry for the world, for peace and love and understanding. It is mainly John’s song.

“It sort of dawned on me that love was the answer, when I was younger, on the Rubber Soul album. My first expression of it was a song called ‘The Word’. The word is ‘love’, in the good and the bad books that I have read, whatever, wherever, the word is ‘love’. It seems like the underlying theme to the universe.”

At the time, Paul strayed dangerously close to pre-empting the following year’s “bigger than Jesus” furore by pointing out that it could be a song for the Salvation Army – “the word is ‘love’, but it could be ‘Jesus’. (It isn’t, mind you, but it could be.)” Certainly the song takes an evangelical approach at every turn (“I’m here to show everybody the light”), it becomes almost surreal as Paul goes on to say “‘Give the word a chance to say / That the word is just the way’ – then the organ comes in, just like the Sally Army.”

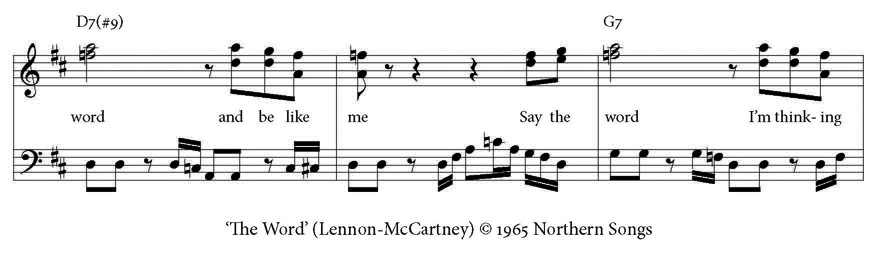

However, the song is less anthemic than, for example, ‘All You Need Is Love’, being edgier, with a less melodic refrain and a rather more forced message. The bridge is a short four bars set against the twelve-bar blues structure of the verse, each time unbalancing the listener, and making it hard to become immersed in the song. And one of the most notable aspects of the track is that, for a song about peace, love and harmony, there is an awful lot of dissonance. In the D7#9 chord, F natural and F# clash for four bars at a time throughout the song, notably when “word” or “love” are mentioned. In many ways the effect is more provocative than harmonious.

That being said, the song has fine touches, from the maracas linking the song to the previous track, to the soaring harmonies on the final verse.

The Beatles recorded ‘The Word’ on 10 November, before starting the second remake of Paul’s ‘I’m Looking Through You’. With the deadline for completing the album in sight, there was no question of remaking ‘The Word’, which was completed on the third take, with bass, vocal, harmonium and maraca overdubs. The stereo mix makes clear the difference between three sets of vocals – John’s lead, the doubling up on the lead and harmony vocals of the choruses, and the high harmonies from the final verse and coda.

As Paul recorded the basic track playing the piano, his bass contribution was recorded as an overdub. A week earlier he had played guitar on the basic track of ‘Michelle’, and so had also overdubbed his bass part. But the guitar was fundamental to the arrangement of ‘Michelle’ – with ‘The Word’, given a choice between playing bass or piano on the rhythm track, he would normally have gone for the bass.

So this would seem to be the first time he consciously decided to wait before recording his bass part. Listening to his bass line, we can perhaps get an idea of his reasoning – during the third chorus, Paul’s bass executes a small but telling flourish.

This subtle, sliding arpeggio of D7 (which also appears in a less arching form in the coda) is an early instance of Paul breaking away from a regular bass line and gives a sign of the crossover taking place between Paul-as-composer and Paul-as-bass player. We have the beginnings of Paul’s considered and original approach to presenting the bass, an approach that would soon flourish into an essential element of the Beatles’ harmonic development, paving the way for the process of recording the lyrical bass lines of Sgt Pepper and Abbey Road.

But all that was still to come – the day after recording ‘The Word’, George Martin headed for Abbey Road’s “Experimental Room” 65 – located just behind Studio One where new equipment was tested and where a mixing desk had recently been installed – and made mono and stereo mixes of the track. He rejected the stereo version in favour of a second mix made the following week. However, the first stereo mix seems to have been used by Capitol for the American Rubber Soul. On that version, the second set of vocals is mixed on the right, with the third vocals, bass and maracas on the left, the reverse of the Parlophone release. The stereo Capitol mix is also unique in having John’s solo vocal double-tracked – all other versions are single-tracked. Although the double-tracking is perfectly acceptable, it may have been felt too ragged for British ears. More likely, of course, is that the failure to mix out one of the double-tracked vocals was an oversight.

In Many Years From Now, Paul tells how, after writing the song, they didn’t produce the usual written sheet of lyrics but, inspired by a joint they had just smoked, created a “psychedelic illuminated manuscript” using what appears to be either watercolours or felt tip pens, featuring multicoloured trees. At the time, avant-garde composer John Cage, a friend of Yoko Ono, was working on a collection for the Foundation for Contemporary Performance Arts to demonstrate the immense variety of ways of notating music. He asked over 250 composers to contribute to the collection, and John gave him the psychedelic manuscript of ‘The Word’. The following year, he and Paul donated lyrics, presented rather more prosaically, of another six songs that appear on Revolver – these were, ‘Eleanor Rigby’, ‘Good Day Sunshine’, ‘And Your Bird Can Sing’ (under the title ‘You Don’t Get Me’) and ‘Yellow Submarine’ written with pen on paper, and ‘For No One’ (as ‘Why Did It Die’) and ‘I’m Only Sleeping’ written on the backs of envelopes. A selection from Cage’s collection was published in 1969 under the title Notations, and all 463 manuscripts used were later donated to the Northwestern University Music Library in Illinois.