In the summer of my sixth year a great expectation arose within me; something overwhelming was pending. I was up each morning at dawn, rushed to the top of Dorchester Hill, a treeless knoll of grass and boulders, to await the sun, my heart pounding. A kind of numinous expectancy loomed everywhere about and within me. A precise shift of brain function was afoot; my biological system was preparing to shift my awareness from the pre-logical operations of the child to the operational logic of later childhood, and an awesome new dimension of life was ready to unfold. Instead, I was put in school that fall. (There was no kindergarten in my day and we went straight into first grade if we turned seven with the first semester.) All year I sat at that desk, stunned, wondering at such a fate, thinking over and over: Something was supposed to happen, and it wasn’t this.

A similar sequence unfolded in my fourteenth year. A huge expectancy arose, more poignant and powerful than the earlier force. This was localized within my chest and what Thomas Wolfe spoke of as the “grape bursting in the throat.” Again I was engulfed in the momentous feeling that something universal and awesome was pending. Puberty had unfolded at the same time, of course, and I found on every hand that this explosive longing of the heart was attributed to sexuality. Sex certainly exploded at that time, too, but it was not at all the same as that affair of the heart. This grape bursting in the throat was far more persistent than the earlier expectancy at age seven, but, as it turned out, not as persistent as sexuality. By my early twenties whatever was supposed to have happened long since had not, the feeling of expectancy slowly waned, and I was left with a sense of loss and despondency that sexual exploration did nothing to abate. The issue within had not been misplaced libido.

Today I speak to some 15,000 people a year, giving workshops and lectures, and I find a universal, unsung lament that summarizes most people’s lives: “Something was supposed to happen but it didn’t.” We read the psychological studies concerning post-coital blues, depression following intercourse, and post-partum blues following childbirth, where as usual, something was supposed to happen but didn’t. There are no studies of the post-adolescent blues because this ailment is generally our permanent state and accepted as our natural human condition.

Ten years ago, through working on my book Magical Child, I found a portion, at least, of what was supposed to happen as a child but had not. I felt relief, as long years of searching seemed to move toward culmination; outrage, for I found that we were vastly more than the behavioristic ideologists had taught us to believe about ourselves; and a renewed sense of expectancy, as though new chapters lay in store for my own life. As I was finishing the work, I had an encounter with a spiritual teacher, which I later described in my book The Bond of Power, and underwent such a dramatic, shaking experience that I felt impelled to withdraw from the world of book-writing and lecturing; disappeared, in effect, and left no address. Something enormous had happened, more seemed pending, and my whole life centered on getting to the core of this event. After three years of this retreat and search, I fell fully into what I now call the post-biological stage of development, that which should have happened, or been initiated, in adolescence. A lifetime of bewildering questions began to be answered (though a new set arose) and I began to understand the self-pitying despondency of our early twenties, when we sense the gross shortchange of our lives and begin that incessant casting about to lay blame anywhere and everywhere. I understood why at about age twenty, even as I attempted to cover my sense of loss by knuckling down to play the game, get those degrees and credit cards, and take my place in the machine, such deep anger festered within me. Something was supposed to happen, and my sense of outrage was justifiable, for, as I found in my fifty-third year, what should have happened earlier is an astonishingly magnificent process.

Magical Child hinted at the great power inherent in our beings. What I have learned since the writing of that book is that such power is a post-biological affair; the development of these powers begins after we have completed our physical maturation. When I wrote Magical Child I knew nothing of a post-biological development; I tried in that book to squeeze everything into the biological period of development of those first fifteen years, which I now realize was a limitation of that book. Because there is a serious discontinuity between the logic of our biological lives and that of our post-biological development, I look for analogies, for metaphors to help bridge the gap. Many of our activities and ideas offer analogies to our own internal states, however, since anything we produce is in some way a reflection of us.

For instance, the wave-particle dilemma in physics is analogous to the difference between the biological and post-biological states of mind. Physicists say both wave and particle states of energy are needed to explain a phenomenon, yet the two—wave and particle—are mutually exclusive. You can observe one or the other but not both at the same time. Physicists speak of wave energy as non-localized; it has no time or space characteristics and so doesn’t exist in the same sense that physical matter exists. The particle, or physical matter, is localized energy; it has a location in time and space. Yet this localized, fixed energy is a restricted way of looking at the non-localized or unrestricted energy. Non-localized energy is an unrestricted field of possibility from which the particle of matter manifests. For the particle to manifest, the field’s open potential “collapses” to that single expression of the particle; and no field is then manifest. For the field to manifest, the particle must respond in its wave form, at which point it cannot exist in its localized way.

In the same way, biological development, of which we are quite aware, is the localized and restricted form of the creative energy of life. Localized energy is restricted or limited to a specific set of relational necessities. Post-biological development is the wave-form corollary of this, in that it leads us to a non-localized awareness, a state of awareness that is unrestricted and fluid, not subject to the rules of relational necessity. In physics this principle of complementarity rules out our viewing both states at the same time, and we must assume the states are mutually exclusive though mutually interdependent. This is a paradox, but paradox is the threshold of truth, for at paradox we must drop the logic applicable to one state and adapt to a new set of rules concerning the new state. Our failure today to meet our problem lies in our inability or unwillingness to shift logical sets. The logic of a particle world will not fit the logic of a wave-form state, and we can operate in only one logical set at a time, at least in our preliminary, biological stage. This is not the case, however, with the mature mind, for full maturation gives us the capacity to leap the logical gap of paradox, allows us access to the excluded middle of logic, allows us to enter into the play of dynamics between reality and possibility. (We find random and rather haphazard forms of this in paranormal phenomena, as, for instance, when we walk on beds of white-hot charcoal without injury or pain, a practice now spreading rapidly in the United States through what is called neurolinguistic programming.)

Our awareness can only unfold from a localized and restricted set of necessary relationships, but once established in this localized reality we can develop a non-localized, unrestricted operation. This is what I call post-biological development. Our first stage of development gives us our awareness of being physical creatures in physical bodies, and opens for us a wonderful physical world for exploration. But physical things are restricted and subject to necessary relationships. All matter decays, and such fragile and complex bits of matter as bodies and brains decay quickly and easily. So as soon as our physical systems are stabilized, a second form unfolds for development, through which we can move beyond this transient physical system. (Whether or not such a development takes place is another matter.) Non-localized reality is a continuum of possibility only; however, to enter into it we must construct a perceptual vehicle (Piaget would say a construction of knowledge) for that kind of awareness.

I cannot deny or eliminate from my discussion the esoteric nature of post-biological development, even though anything esoteric seems foreign to our culture. The complementarity of quantum mechanics is quite esoteric, even to many physicists (who turn their backs on it, preferring to stick with the good commonsense logic of particles). And since our Western culture drove all traces of post-biological development underground centuries ago, I have to risk credibility in discussing it. Post-biological development survived in the East, rather underground, too, perhaps, but in a strong, substantial way, in what is called yoga. The word means yoke or union, and the union is between local and non-local states (at least for now). To shift from locality to non-locality is to shift logic and perceptual sets. Our physical bodies are the perceptual set and logic of local reality. Nature devotes some fifteen years of each human life to establishing this system, and we take this extraordinary creative process for granted. At its completion she opens the developmental means to create a corresponding logical and perceptual set, or vehicle, for exploring non-local possibility. It is as simple, as logical as that.

Two short quotations may indicate the direction of this esoterica: one is from the East, given by Mircea Eliade in his book Yoga: Immortality and Freedom (N.Y.: Pantheon, 1958). The other is from the recently discovered Nag Hammid library, a set of codices concerning the sayings and actions of Jesus according to the very early Gnostic “followers of the Way.” (In a fierce struggle lasting some two centuries, the Gnostics were driven underground and largely destroyed by the bishops of the early Christian church. These Gnostic codices, some of which may be older than the oldest of the Gospels of the Christian New Testament, touch on the sublime among much that is ridiculous. A few pearls are buried in a field of—at times—unintelligible gibberish.)

Eliade quotes from Further Dialogues of the Buddha: “I have shown my disciples the way whereby they call into being out of this body of four elements another body of the mind’s creation, complete in all its limbs and members, and with transcendental faculties.” And in the Gnostic Gospel of Thomas we find: “. . . when you fashion an eye in place of an eye, and a hand in place of a hand, and a foot in place of a foot, and a likeness in place of a likeness, then you will enter the kingdom. . . .”

Nothing in our popular concept of yoga (the healthy, poised, and sexy body) or in Christianity suggests anything about a mental body we must create to enter the kingdom within. We had to create our physical bodies and their perceptual systems, however, as Piaget makes clear, so why should it be any different with a non-physical system? Non-local possibility has no reality except as we create a reality out of it; it has no existence until we give it existence by our attention and energy. To learn of an open-ended nature we must create an open-ended perceptual system. All developmental researchers agree that growth of intelligence is a movement from early concrete thinking to abstract thinking. They recognize that genuine abstract thought unfolds around adolescence, but they have no inkling, apparently, of the real dimensions of this non-localized, or abstract, realm.

Since post-biological movement is based squarely on the biological, nature has arranged that this second stage unfold at puberty, when we move into the final stage of physical growth and general biological orientation. A neat overlap is thus provided, since the only way into the non-localized state is through the conceptual patterns achieved in our biological development. This second stage of life is the real subject of this book, but since it is based on the first stage, I must, of necessity, outline the earlier, biological development to some extent. I have found that the first stage, the biological, unfolds correctly only when in the service of the second stage, only when it leads toward and prepares for the mature unfolding. A rule of development is that each stage, while perfect to itself, is fulfilled only as it is integrated into the next higher structure of knowing.

In the same way, life achieves its perfection when it fully prepares us for death. Near-death experience has recently been a topic for best-selling books, but the implications of the death-and-dying movement are misleading. There is a tendency to heave a sigh of relief and, thinking all is well, just wait for the ending that is also a beginning. The idea of a post-biological development thus becomes superfluous since all is well with no effort on our part. The truth we need lies in post-biological development and always has, but in this age of contrasts, the cosmology of the death-and-dying people, available to all, stands at a neat polarity with the equally popular but unavailable rigors and terrors of Carlos Castaneda’s taking of the kingdom by storm.

Meanwhile, we face a very real possibility of global extinction by our own hands. This threat, I think, throws the psyche of the globe into what might be thought of as a healthy crisis. It confronts us with an imminent death we would otherwise deny, which just might be the shock needed to wake us up. Scientific people, particularly the medicine men, have been covertly hinting at the ultimate magic for several decades now: the subtle suggestion that given enough money, prestige, fame, Nobels, and adulation, they just might not only extend our lives but even outwit death indefinitely or entirely. Even to entertain such a notion (and we have been actively seduced by it) is to lose the meaning of life, which brings on the necessity of the threat of mass death. For life and death are the perfect complementaries: mutually exclusive yet interdependent. Without death life loses meaning, for this earth is not a permanent home, by design or nature. It is our kindergarten.

Actually, the bomb offers nothing new at all, in one sense: None of us can—or has ever been able to—guarantee himself one extra heartbeat. The issue of the bomb simply presents to us culturally what we have tried to deny individually. Each stage of our development is meaningful and perfect only as it leads naturally into the next stage. The perfect pregnancy prepares for and leads to childbirth, the termination of pregnancy. Leaving the womb provides entry into a far less restricted world and the opening of a new development. The perfect life prepares for the termination of life. We leave our biological womb to move into non-biological realms. Everything that happens in the womb prepares the infant for the new life outside it, and everything in our lives, while complete and rich in itself, prepares us for life beyond it, or is supposed to. As preparation for birth can only take place in pregnancy, so preparation for the non-biological state must be made while in the biological.

I travel around the globe giving workshops on development some eight months of the year. (The other four I spend in Ganeshpuri, India, concentrating on my own post-biological development.) I am struck continually by an apathetic anxiety that has spread abroad, in parallel with an excited optimism in that segment of people involved in or following the explosive developments in brain research. The brain/mind has finally been sensed as the key to things, and people from all walks of life and every branch of science are getting into the act. Marilyn Ferguson, in her Brain/Mind Bulletin, reports that some 500,000 published research papers are now appearing yearly on the brain/mind issue. An effort of such magnitude, of course, produces varying results; and though the percentage of significant discovery might be small, it grows in keeping with the magnitude of the labor. Research strikes me as valid when it contributes to a functional, meaningful self-portrait. The human is not just the measure of the human; any and every view of the universe we make is anthropomorphic and autobiographical. The portrait of ourselves that is emerging from brain research is awesome, but one must keep collecting the bits and pieces and “look for the pattern which connects,” as Gregory Bateson urged. From the portrait I have found emerging, I am as optimistic about the survival and triumph of human society as I am pessimistic about the survival of a technological culture. For everything points toward something the yogis and sages of all ages have recognized: We are the vehicles of creation itself, the physical embodiment of the Creator. Though this expressive body seems at the point of death from self-inflicted wounds, we have within us a recovery capacity equal to our folly.

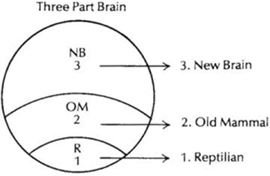

The following sketch of development is offered in this spirit of optimism and pessimism, in fair measure. We must all walk in a tightrope venture between ecstasy and terror—things can go either way. For me the balancing act involved takes place squarely within the frame of yoga, which admittedly tips the balance toward ecstasy without denying the terror. Yoga, which means yoke or union, is the path to the union of our human and divine natures. This is the only path to the truth of our being, the way out of our current impasse. It is what the post-biological plan is all about. Within this yogic frame of reference I find the “triune nature of brain” offered by Paul MacLean easily the most important item in current brain research. And I use the equally important theories of formative causation offered by biologist Rupert Sheldrake; physicist David Bohm’s holonomic movement; the general principle of complementarity given by physicists Minas Kafatos and Robert Nadeau; and, of course, the developmental stages outlined by Jean Piaget. All these contribute fresh vitality to our yogic “skeleton,” and, as good bones should, they support the work to follow without becoming obtrusive. That is, we should not notice their presence at all times, though at intervals we may need to lay them bare to make a point.

This book presents a cosmology, an outline of creativity that embraces our experience. We are the measure of ourselves and in taking our measurement we find that we have measured our universe and its creation. I think this gives us a functional outline of who we really are, and by functional I mean one that works toward our well-being. Our current behavioristic models have led us to death and despair since they have left out everything that truly makes us tick. They left out the juice, the meaning and purpose, and left us with knee-jerk reflexes. One example, fire-walking, calls the lie to this monstrous error of behaviorism. The model of ourselves that leads us to freedom is one that encompasses anything and everything within our experience, an open-ended yet structured model. Our self-portrait must have room for the precursory modes of intuitive, non-verbal awareness; must give a means for explaining such diversities as that 40,000-year heritage of the Australian Aborigine called Dream Time; the symbolic, make-believe world of my three-year-old; the ecstatic experience of the Kalahari ¡Kung, dancing about their fire and raising their Kundalini; Kekule’s Eureka! experience of a ring of snakes that translates to the language of chemistry as the benzene ring, the basis of all modern chemistry; and must make room for a workable notion of the relation between consciousness and reality.

Any outline of intelligence is meaningless and sterile unless it deals immediately with spirit, for spirit is the central nexus of human experience. Nor can spirit be added as an afterthought, like salt thrown in to flavor the stew, or a sweet postscript added for the spiritually inclined, like a politician throwing in a reference to The Lord with tremorous, pious voice. Spirit must be foremost in our considerations from the beginning if development is to be seen in its full scope, and if we are to avoid the common pitfall of a self-encapsulated intellectual trap. Spirit is the spine and skull of our developmental skeleton, and the spark of the intelligence behind it. Upon spirit all the various scientific ribs hang beautifully and make coordinated sense; without spirit we have fragmented nonsense.

Perhaps the scope of this work sounds a bit broad for a single volume, and I can hear complaints (similar to those made of my less ambitious Magical Child) that this book attempts too much. But I argue that all too often we attempt too little. Better an impossible task of splendid proportion than a sure but piddling one of no consequence. We learn from failures as well as successes.

Another problem is that words are not always the best tools for presenting these ideas. I continually search for metaphors, models, examples, and analogies that might help readers grasp rather intangible functions, and I have devised a number of sketches to display these models visually. Even though models and sketches always betray the functions they represent, they do give us visual footholds in otherwise slippery terrain.

Here, for instance, is a sketch of our triune brain system.

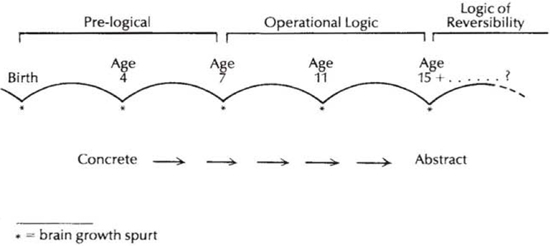

Can you think of anything more ridiculous than representing the most complex structure known in the universe through such a model? Yet we cannot grasp the meaningful functions of the brain if we are mired down in that incredible complexity. And here is a sketch of our first fifteen years of development, those critical biological years which give the foundation on which the post-biological rests.

Can this skinny little diagram in any way represent the richness of our experience as children and adolescents? Yet these are valid and valuable aids, signs by which we can thread our way through a maze of otherwise abstract descriptions.

Sketches and models can trip us. I recall a workshop in Sydney, Australia, the audience for which included a psychologist who began to fidget from the moment I introduced MacLean’s triune brain as my basic model of child development. Finally, the good man could contain himself no longer and blurted out: “But what about the fontanels?” Ah, the fontanels. Our psychologist had had a course in anatomy once and remembered the fontanels. (Fontanels are those points of the skull where the bones do not come together in the uterine infant. One major one, at the top of the head, remains after birth, the well-known soft spot where the blood can be seen pulsing beneath the skin. Thus the term fontanel—little fountain. Not actually a brain part, just a temporary condition; the lack of relevance to development made the psychologist’s distress all the more ludicrous.) I was going full steam down the developmental track, riding this engine of the triune brain, with its physical, emotional, and intellectual passenger cars, but where were those fontanels? Our good man missed the train, wasted his ticket, and floundered around back at the station, trapped in the baggage of his own information.

I am aware that my models betray the functions represented, that I don’t address the fontanels. But my models do help indicate those developmental functions in a concrete, tangible way that makes them available to our observation. So, arbitrary as they are, follow along with my oversimplifications; withhold those obvious qualifications that cry out to be acknowledged until you see where my over-simplified models lead. Time then for fontanels and all our qualifying pets (for all of us have our own repertoire of qualifications). Go along with the notion that age seven is the statistical line of demarcation between pre-logical and operational child, even though your own little genius displayed all this at age five. Myriad qualifications will arise, but within the framework that also develops, any number of qualifications can be made without loss of a functional overview that bestows meaning, order, and purpose.

Readers of Magical Child and my earlier Crack in the Cosmic Egg will find few research references or names in the text of this book. I draw on a wide spectrum of current research, and numerous footnotes refer the reader to my sources. But a constant academic name-dropping, which our consensus security seems to demand, clutters the reading and obscures the line of thought. So, again, I urge you to follow the string all the way through the maze here before you plunge off into the myriad byways. Remember that once we have awakened from a dream we are not required to go back into that dream to straighten out its mess. Once awakened within us, post-biological development invites us, in turn, to wake up. My bibliography and footnotes—in fact, all words entirely—may eventually pale to insignificance and become superfluous, once we glimpse, even briefly, the state beyond our current dream.