“Eat,” the Elder Caliph repeated. “And be free.”

More people had arrived; the line had grown so long that it snaked away from the Blighted Tree like a long, rippling ribbon. Prue recognized more faces in the crowd: the Spokes who had carried the rickshaw when she’d first arrived, the girl who’d given her flowers when she first stepped into the Mansion. They all stood quietly and obediently, one behind the other, waiting for their time to be fed the strange substance by the hooded Caliph. The ever-present HUM continued unabated in Prue’s mind, and her vision swam as she teetered by the tree and tried valiantly to reconstitute her thoughts. The Elder Caliph, Elgen, had taken the spoon of Spongiform from the acolyte and was holding it some few inches from Prue’s lips.

“Esben,” murmured Prue. “I need to get to Esben.”

“Esben is safe,” said Elgen. “He’s in good hands.”

This seemed to shake Prue from her swoon. “He’s hidden. You don’t know where he is.”

The man was growing impatient. The fungi quivered on the proffered spoon; it was a glowing brownish green. “As we speak, your friend Esben is being fetched and brought here. Soon he will be united with his old compatriot, Carol, and the reconstruction of the mechanical boy will commence. We’ve achieved your directive, Prue. We’ve done it together.”

“No!” shouted Prue, deeply shaken. “That’s not how it was supposed to happen!” The HUM grew louder; a shimmering rainbowlike aura had overtaken the margins of her vision. She wasn’t sure what was happening; she was feeling the world giving way.

“It’s all foretold, Prue. It was all written, long before you arrived. See: Even now, your friend the badger is here for the fungal communion.”

Sure enough: There was Neil, shipped to the front of the line, preparing to receive his dose of Spongiform.

“We are the eyes and ears of this forest, Prue. No action goes unnoticed. Surely you didn’t think we wouldn’t follow you, wouldn’t want to find out where you were keeping your ursine treasure.”

Prue stared wildly at the badger; he seemed oblivious to her presence, so great was his desire to receive the substance being fed him. “This can’t be happening. This isn’t happening. I must be dreaming. This isn’t real.” The words came flowing from Prue’s mouth; she couldn’t shake the HUM, the incessant ticking from the surrounding acolytes. The ticking grew louder as she felt two figures come up behind her and hold her shoulders, hard.

The Elder Caliph persisted, “Your life, one way or another, is forfeit, Prue. Your mission is finished. Your sentence had already been written; think of this as a commutation of that sentence. In exchange for a lifelong devotion to the birthing of the One Tree. Yes: The Mansion has already turned against you. They did the moment you started speaking that hogwash about reviving the ‘true heir.’ Do you think for a moment that they wouldn’t want to defend their positions? Do you think for a moment that your black magic interests wouldn’t strike fear in their hearts? Feed on the Blight and save yourself from a fate worse than death.” Elgen held the spoon to her mouth. She could feel the cold moistness of the Spongiform touching her upper lip. “Come now, Prue. Just eat it.”

PLEASE, thought Prue, and she felt the grass below her feet spring to life. It wrapped around the feet of the Elder Caliph, and he choked back a shout of surprise. He merely needed to look down at his ankles for the grass to release its hold, though; new tendrils sprouted below Prue’s feet, and suddenly she realized that it was her feet, instead, that were now tied to the ground.

“Foolish,” said Elgen. “You have no power here.”

He nodded to one of the acolytes at her side, and she felt fingers curling around her neck, under her jawbone. She felt her mouth forced open. The ticking emanating from her captor was jarring in its volume. She strained to see his face; it was covered in a silver mask.

“Who are you?” she managed. His grip tightened; her mouth was opened wide now. The fungi made its way into her opened lips; she felt the cold of the spoon on her tongue.

Elgen answered for her: “They are the voice of the Wood, Prue. The sons and daughters of the forest. The midwives of the new world. And now you will join them.”

Prue let her body go slack; her jaw slid open to receive the Spongiform.

She felt the hands at her jaw loosen their pressure. The bodies at either side of her seemed to relax, assured of their subject’s surrender.

And that was when she acted.

The weird fungus had barely touched her tongue, an acrid, bitter flavor spreading out through her taste buds, when she spat it out with all the power she could muster. It exploded into little pieces and spackled the gold mirrored mask of the Elder Caliph before her. Simultaneously she jabbed her elbow as hard as she could into the stomach of the acolyte to her left and felt his body crumple at the waist. Pivoting to her right, she faced her second captor and, despite a prevailing instinct to not hit anybody, let alone someone wearing a mask that looked decidedly hard, she seized her right hand into a taut fist and slammed it into the acolyte’s masked face.

The mask, seemingly made of crystal, shattered.

The face beneath was revealed.

“Brendan?” she managed, completely shocked. The red beard, the quiet eyes, the tribal tattoo on his forehead. It was all there.

Whatever energy, whatever momentum she’d collected in her adrenaline-fueled surprise attack on the Caliphs of the Synod was gone in that moment. She was floored by shock and despair. Her hand, aching from the strike, fell to her side. The HUM was everywhere. She stared into the Bandit King’s eyes in disbelief, trying to find her old friend somewhere in there. His eyes were still, almost lifeless. The ticking seemed to grow from his eye sockets, from his nostrils, and it soon became the only thing she could hear.

Until another voice spoke. “Your chance has come and gone.” It was Elgen. He spoke now to a mob of acolytes who’d arrived at the scene of the scuffle. “Get her on a ship,” he said, wiping the bits of Spongiform from his mask. “Let her rot on the Crag.”

Prue, in despair, let her body surrender completely, and she was pushed rudely away from the congregation at the Blighted Tree. Every possible iteration of the previous year’s events was flowing through her mind as the HUM receded and she stumbled in the captivity of the two acolytes down the sloping hill toward a line of trees. She found herself numbly mumbling to herself, saying things like, “Brendan. Here. The Synod. How could this?” She looked up at her captors: the masked acolytes. “Who are you?” she asked. They did not answer.

The illumination of the line of torches in the meadow had faded away; a group of men holding lanterns met the group of Caliphs and their prisoner at the tree line at the far side of the meadow. The men seemed shocked to see it was Prue.

“This is the one? The one for the Crag?” asked a bearded man in a dark mackintosh.

The acolyte at her side said nothing; she was pushed forward into the arms of the group of men. They held her fast, each one looking at the others in confusion. Prue shook herself from her reverie and said to them, “This is a terrible mistake. The Synod, they’re poisoning people. All the acolytes, they’ve been drugged!”

The men looked back and forth between Prue and the acolytes, drawn between two resisting forces. In the end, the more powerful won out.

“Bind her wrists, men,” said the bearded man. “Get her down to the ship.” His tone was sorrowful, surrendering.

“NO!” shouted Prue wildly. Tears were now streaming down her face. “I need to get to Esben!”

“Shhh, Maiden,” said the man at her right arm. “Don’t make it worse for yourself.”

They marched her into the trees, down a well-worn and rutted path. A thick cord had been tied quickly around her wrists, and the tough material bit into her skin. The men smelled of sweat and pitch; Prue noticed they each wore the same little black stocking cap, the same weathered mackintosh; the thick, waxed material of the coats reached down to their knees. They seemed to be fully bearded, to a man. “Where are you taking me?” asked Prue, when she’d gathered her senses.

“I’m very sorry it’s turned out like this, Maiden,” said one of the men. “But it’s for the good of all.”

“What ship? What ship are you taking me to?”

“The Jolly Crescent, Maiden,” said another man. “She’s in dock now. Won’t be long. Best to just be quiet. Don’t put up a fuss.”

Prue frowned and watched the road ahead of her; with her hands shackled behind her, she could feel her shoulders smarting in their sockets. She tried to relax, to focus on something other than the pain her rope manacles were causing her. She looked to the vegetation surrounding the path and began to speak.

WHIP, she thought.

A branch above their heads bowed a little, but soon shot back into place. That ever-present ticking noise, the one coming from the acolytes, had suddenly risen in a crescendo, and she looked behind her to see that they were being closely followed by a group of hooded, masked Caliphs. She tried again: willing her thoughts to the surrounding woods in hopes that some assistance might be given, the way that she had briefly ensnared the shape-shifting Darla Thennis when they had faced off in the refuse heap. Still, nothing. She was being blocked somehow.

She tried another angle: “You know they’re cutting peoples’ heads off for stuff like this. I mean, I’m the Bicycle Maiden. I’m the face of the revolution.”

This got no response. The men’s faces were steely and quiet.

“Aren’t you afraid? I could raise an army! I could have all of you, each one, up against the wall in the bat of an eyelash.” The color was rising in her face, she could feel it. She was speaking from some deeply recessed well; she was channeling all her anger into her voice.

“Times have changed,” said one of the men dolefully. “It’s the Synod, now, that everyone is looking to.”

She jerked her head over her shoulder, looking at the several Caliphs who were following them down the rocky path. “You!” she shouted. “Who are you? Are you bandits? Are you Wildwood bandits?” She focused on them, hearing the ticking noise, trying to deduce some kind of language or syntax from the sound. The Caliphs did not respond. Their mirrored face masks glinted in the low light.

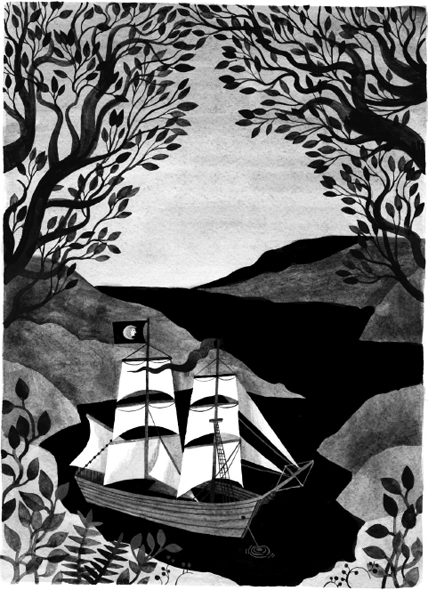

They walked for many hours, following a maze of paths that led down a steep hillside and through the thick of the trees. After a time, a light could be seen glimmering through the woods: Prue saw that it was the city lights of Portland, of the Outside. They were nearing the Periphery, the edge of the Wood. The path they were following snaked along the steep bank of a rushing creek that, some many yards down the hill, opened up into a watery inlet, surrounded by a thick weft of trees. In this inlet was anchored a very large and very old-looking sailing ship, its bevy of massive sails sitting dormant in the still air.

It looked to Prue like the ship had been swept ashore from some long-gone century, something that would be more at home battling Nelson’s tall ships at Trafalgar than sitting dockside in a quaint, twenty-first-century Pacific Northwest river inlet. A moon-woman, half flaxen-haired lady and half crescent moon, was the ship’s figurehead, and the shutters and eaves of the vessel’s many windows were painted bright blue. The ship’s central mast reached easily as high as the closest Douglas fir tree, and a veritable spider’s web of ropes and rigging stretched down from its spire to the dark decks below.

Several fellow mariners came rushing up from the dock when they saw Prue and her captors approach. “What’s going on?” shouted one. “Who’s this?”

“Our instructions,” said one of the men holding Prue, “are to bring this one to the Crag.”

Soon, a crowd of seamen had gathered to greet the newcomers. “Ain’t that the Bicycle Maiden?” said one.

“Aye, ’tis,” confirmed one of the men at Prue’s side. “She’s been indicted.”

Before any of the men had a chance to speak their disbelief, they saw the hooded Caliphs appear from behind the group. It was all the proof they needed that the sentence was lawful. They cowed, visibly, under the presence of the masked men. A man with a blond, wiry beard and a black visored cap came forward. The other men seemed to step aside in deference to him, and he spoke with an uncompromising authority: “This is the one?”

One of the Caliphs nodded solemnly.

“Very well,” said the man. “Let’s get her onboard.” He looked at Prue and said, “I’m very sorry this has to be the way, miss. I’ll try to make your passage as comfortable as I can, given the circumstances. My name is Captain Shtiva. The Jolly Crescent is my ship. Long live the revolution.” He paused and glanced at the Synod members present. “And long live the spirit of the Blighted Tree.”

“Where are you taking me?” asked Prue. She still wasn’t entirely clear what was happening to her. “What have I done?”

The man, Captain Shtiva, frowned. “You are an enemy of the state. I have written authority from the Interim Governor-Regent-elect to carry you to your permanent incarceration on the Crag.” He held up a long and wide envelope, its seal freshly broken. “In the event of your not capitulating to the demands of the Synod.”

“Enemy of the state?” gasped Prue breathlessly. “I’m the hero of the state! They’re poisoning the people—they’re feeding them that stuff—on the tree! It’s changing them! I saw the Bandit King—the Wildwood Bandit King—behind one of those masks! I think there may be more bandits among them! Something very terrible is happening, Captain. I need to stop it. Please, let me go! I have orders from the Council Tree. I have to rebuild the prince. I have to find the makers to reanimate the half-dead prince!” The words now were flowing from her mouth in jerky rivulets. She could feel the spittle flying from her lips.

The captain watched her with a look of abject pity on his face. Her entreaties seemed to make no dent in his resoluteness; if anything, her every word seemed to erode whatever pity he had stored up. He seemed to look at her as if she were speaking a foreign language. “Get her onboard,” he said finally. “There’s a berth for her in the lower hold. Make sure she’s locked up tight.”

The men began to hustle Prue away when the captain turned and said, “But keep her safe. I don’t want any harm done in the process. I will not have my hands bloodied further. Is that clear?”

The men murmured their understanding; Prue was led down the path to the bottom of the bank, where a worn dock spread out from the ground into the placid waters of the inlet. The sailors holding her tied hands sniffed at the air; one said, “No mist. How we gonna get to sea?”

“Let the captain manage that,” another said. “Let’s get this one belowdecks.”

Lanterns, hanging from the stout wooden pilings along the dockside, lit the way as Prue was led toward the awaiting ship. She could see the winking lights of the Industrial Wastes just beyond the shade of the trees that marked the boundary between the Wood and the Outside; she assumed the Periphery, that magic ribbon that served as the protective shield around the so-called Impassable Wilderness, was somewhere in her vision, invisible.

The ship swayed as they stepped onto the deck; a crowd of like-dressed sailors stood, mopping the boards, coiling rope, shouldering wooden crates. Prue was escorted toward an opening in the floor; arriving there, she was instructed to climb down a stepladder. A smell of stale beer and moldy cheese attacked her senses as she arrived at the rough wood floor of the belowdecks. Down a crowded passageway she was led to a door made of iron bars, which opened onto a small, closetlike hold. A cot and a tin pail were the room’s only furnishings. A porthole above the cot, its glass pane hatch-marked with iron bands, looked out onto the dark harbor.

Something cold was pressed to her wrists; her bonds fell away and her hands were freed. She rubbed at the sore, reddened welts the ropes had left. Her captors seemed unconcerned that she would attempt any kind of escape.

“Make yerself at home,” one said. “It’s a long journey.”

“Where are we going?” asked Prue. To her recollection, there wasn’t any kind of inland sea in the Wood; if her direction sense was not failing her, they would be plying the waters of the Willamette River.

“To th’ Crag,” said the other.

“What’s that?” When she sensed they were not about to tell her, she tried on her best twelve-year-old-girl pleading voice: “Don’t I have, like, a right to know?”

The two sailors looked at each other uncertainly before one said, “I’ll tell you as much, seein’ as how you’re the Bicycle Maiden. I don’t cotton to what they’re doin’ to you here, but I’m just under orders, right? You’ve been sentenced to the Crag. It’s a rock out in the ocean. It’s a hard, barren place. There ain’t no escapin’ it.” He looked saddened by this description. “I expect you’ll live out yer days there, miss.”

Prue gasped. “What?”

The man shrugged. “Orders, miss.”

“For the good of the revolution,” said the other.

The door was closed in her face, and Prue felt her knees buckle out from under her; she caught herself on the lip of the cot and sat down heavily, her head in her hands, and began to cry. Loud, heaving sobs. They seemed to bucket up from the deepest wells of her gut.

Voices could be heard through the locked door. “Shame, what they’re doing,” said one sailor to another. “A shame.”

“Well, we ain’t going anywhere till we got a mist.”

“It’ll come. Calling for it tonight.”

“Believe it when I see it. C’mon.”

Footsteps trundled up the stepladder; the hatch slammed noisily down behind them. Prue was alone in the hold of the ship. She looked over her shoulder at the dark porthole. Standing on the thin mattress, she peered out the dirty window to watch the lantern light reflected against the water of the placid inlet.

Time passed, slowly.

Far off, the stars were beginning to be blotted out by an approaching fog. Prue turned her face away from the gray window and stared at her small prison cell. She thought about what she’d done, what had transpired to this point; she thought about the great mess she’d caused. She wondered, as people often do when faced with the very real consideration that all their plans have failed miserably, how it could be possible that she could go so wrong. Why had the tree picked her? Why had she received this communication? Certainly, there were people more qualified for the job of wrangling two missing machinists from exile to re-create a robotic boy prince in the wake of a popular revolution and an aggressive religious takeover.

The hatch on the above-decks opened, and a figure moved silently down the ladder. Prue looked over to see that it was one of the Caliphs, the silver-masked Mystics, come to hold vigil.

“Hi,” said Prue.

The Caliph didn’t respond. Instead he sat down on a chest directly across from the barred door of her cell. Straightening his shoulders, he set his hands calmly on his robed knees and stared straight ahead, his mask glinting in the low candlelight. The ticking noise sounded in Prue’s ears, like a winding clock.

“What’s your name?” tried Prue again. “Are you one of the Wildwood bandits? Jack? Eamon?”

Nothing.

“Right, vow of silence.” Prue crossed her arms and stared at her feet, at the tattered canvas of her Keds.

The ship bucked in the current of the river; the boards moaned under the pressure, and Prue could hear shouting from the sailors on deck. The hatch door opened suddenly and a voice called in: “Underway!”

The Caliph on the chest did not move; he only stared straight ahead.

The hatch door closed and Prue lay back on her cot, staring at the ceiling. The ticking was there, in her mind, sounding to her from some strange source inside the Caliph.

She waited. The night poured on, like a thick syrup. Somewhere, distantly, an explosion sounded.