In the woods, there lived an owl.

He was a quiet owl, one who liked to keep to himself. He considered himself lucky to be living in a fairly untrammeled patch of the forest, and he rarely had much fuss with his neighbors. He slept through the days, typically, in a cozy nest he’d built in the hollow of a very old tree, which had snapped in half during a storm some twelve years prior. The hollow made a very nice home for an owl who was getting on in years.

He had relatives who were living in other, more populated areas of the Wood, and they were forever bothering him to come and join them; that somehow, in his advanced age, he could benefit from the help of others. To him, this suggestion implied that he was unable to look out for himself, and he took umbrage at this. Deep, deep umbrage. It only made him more content in his daily and nightly habits, his everyday activities, here in this farthest frontier of the woods in his quiet and cozy hollow-of-a-tree.

Every day, he slept away the sunlit hours and woke himself at dusk. Every night, he busily tidied his hollow-of-a-tree and then set out for his breakfast, which happened at night, as it does for most owls. However, rather than expending an awful lot of energy, flying around and searching the forest floor for food, this owl simply climbed out of his nest and made his way, slowly, some three feet down the edge of one of the tree’s surviving limbs and sat there for the remaining hours of the evening, watching the ground. Occasionally a small rodent would run across his field of vision and he would unfurl his large, weatherworn wings and soar down and grab it for lunch or dinner, depending on what time of night it was. But mostly he just sat there, staring at the ground.

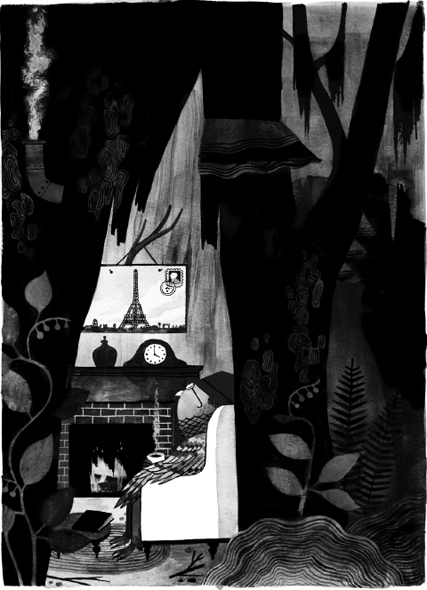

When the first glints of sunrise awoke the early morning birds and the waxy leaves of the salal vines glowed in the light, the owl would yawn and make his way the few feet to his nest in the hollow-of-a-tree and happily brew himself some hot chocolate and cozy up with a book in a small chair by the fireplace and doze off.

Life went on like this for the old owl, fairly uninterrupted, until one day, while he was holding his vigil on the tree limb, casually scanning the darkened underbrush for rodents, as he did every night, a slight tremor alerted him to someone or something that had joined him on the branch.

He looked over to see that it was a squirrel.

“Go away,” said the owl.

“What’re you looking at?” asked the squirrel.

“Nothing,” said the owl, not wanting to engage the newcomer in conversation. He enjoyed his privacy, his solitude. He wished the squirrel would respect that.

The squirrel cocked his head. “Nothing? Like, nothing?”

“Nothing,” said the owl. “Now leave me alone.”

The squirrel remained, transfixed, as the owl was, on the ground below.

“You’re still here,” said the owl, after a time. Which the squirrel was.

“How do you do it?” asked the squirrel.

“Do what?”

“Just sit here, staring at the ground. Don’t you get bored?”

“For your information, I am hunting,” said the owl. “I am hunting for small, furry creatures that I might eat. Technically, you fit that description.”

“Is that a threat?”

“I’d just prefer to be left alone, is all,” said the owl with a deep sigh.

“I get it,” said the squirrel.

They sat in silence for a moment, while the owl continued to search the ground. He didn’t like confrontation or conflict, this owl, and so he chose to simply pretend that the squirrel wasn’t there. He would make good on his threat and eat the squirrel, except that the owl didn’t particularly like the taste of squirrels—and, what’s more, they were a little too big for him. Maybe in his younger days, but now, he found he preferred the ease of hunting mice and voles and the like.

“Question,” said the squirrel.

“What?” asked the owl, annoyed. Perhaps if he engaged the squirrel briefly, he could satisfy the animal’s curiosity and he would then leave the owl in peace.

“Don’t you think there’s, you know, more to life? I mean, more than just sitting here on this limb and waiting for some food to come walking along.”

“What do you mean?” asked the owl, now having a hard time pretending the squirrel wasn’t there.

“You know, seems an awful waste of one’s time on this stretch of earth, just satisfying the urgings of the old tummy without a thought given to the bigger questions of the day.”

The owl thought about this for a second, before replying, “Seems okay to me.”

And then: “Seems like a very good life, actually.”

The squirrel shook his head. “But there’s, like, a whole world out there! Filled with mystery and awe and sorrow and happiness. And all you’re doing, night in and night out, is sitting on this old branch and watching for a mouse to come along.” The squirrel held out his paws, palms up, and shook them. “Don’t you just, you know, long for more?”

“Guess I hadn’t thought about it that much,” was the owl’s reply. “Now if you wouldn’t mind, I don’t want to—”

“Hold up,” said the squirrel. “Can I show you something?”

“No,” said the owl.

“Oh, c’mon,” the squirrel chided. “It’ll just take a sec.”

The owl glanced ruefully at his branch-mate and gave no answer, which the squirrel took to be an emphatic yes. He held up a single digit of his paw before leaping from the branch and disappearing into the canopy of trees.

Hmm, thought the owl. That was easy. He returned his attention to the ground below, a dark blanket of ferns and vines, hoping for the promise of a lunchtime meal. He sat there for a time and only occasionally did his thoughts go to the squirrel and his strange question about the nature of the owl’s simple and, he had to admit, fairly contented, way of life. Why should he long for more? Wasn’t everything he needed right here? Wasn’t there a kind of solace in the repetitions of his life, how every evening and every day were, more or less, exactly the same, barring whatever minute interruptions he might have to suffer on very rare occasions—like, say, a squirrel distracting him from his nightly surveillance? Oddly enough, the more he pondered these questions, the more he began to see holes in his timeless logic. Maybe the squirrel was onto something. . . .

Before he had a chance to delve deeper in his own meditations, the branch shook and the squirrel reappeared at the owl’s side. “Hi,” said the squirrel.

“Hi,” said the owl.

The squirrel was carrying something. He held it up and showed it to the owl; it was a large postcard, human-sized, and on it was a photograph of a very strange and elaborate structure. The structure seemed to be made of sticks, or sticklike objects, and it stood on four stick-made legs. The sticks made a kind of lattice as the four legs met each other at the midsection, and from there a pinnacle-like tower sprouted upward, skyward, to reach a fixed point at the very top, which seemed to end in a spired arrowhead-like design. What’s more, there seemed to be a viewing deck at the top of the structure; small figures, ant-size relative to the structure they were standing on, milled about on the observation deck.

“What is it?” asked the owl.

“That’s the thing,” said the squirrel. “I don’t know. But look at it. Look at that thing. I have no idea how big it is, or how many squirrels it took to build it, or even where it is. This picture just literally fell out of the sky one day while I was busily collecting sunflower seeds. Like you, I spent my days as if I were adhered to a track, like I was trying, busily, to simply re-create the exact events of the day before: forever collecting seeds and nuts, forever skittishly running up and down tree trunks, forever making this kind of weird squeaking noise with my front teeth.” Just then, he made the noise. It surprised the owl, whose attention was firmly engaged with the picture the squirrel was holding. “See?”

“Mm-hmm,” said the owl.

“But boom. This picture floats down from the sky and I look at it and suddenly—wow—my worldview, like, instantaneously doubles. Or triples! And suddenly my rote daily exercise of sustenance and survival seems awfully puny in the face of such, like, flourishes of creative spirit. You know? Simultaneously, I experienced this very true understanding—this epiphany—of the oh-so-trivial nature of life, and yet, despite the trivialities, a life that is so full, so chock-full, of an almost infinite promise. You see?”

The owl was dizzied by the squirrel’s monologue. “I guess so,” was all he could say.

“It’s okay,” said the squirrel. “I was where you were, once. I was in the dark. My eyes were closed to the possibilities.” He flipped the postcard in his fingers, away from the owl, and gave it a long glance. He then handed it to the owl.

“Here,” he said. “I want you to have it.”

The owl gulped. “Don’t you want it?”

“It did me some good. Time for me to pay it forward.”

“Okay,” said the owl, taking the postcard in his talon. And then: “What are you going to do now?”

“I’m off to have some adventures,” responded the squirrel. “I’m off to see the world.”

And with that, the squirrel gave the owl a puckish wink and a little salute. He then tiptoed off the end of the branch and nimbly dove into the surrounding dark.

The owl sat for a time on the branch, alternately looking at that same patch of forest floor he had for years upon years, and looking at the postcard picture the squirrel had given him. The thing—the tower—on the postcard was truly a work of dizzying beauty. The night passed like this, with the owl in deep contemplation. Finally, a hint of sun broke through the low branches of the Douglas fir saplings, and the forest awoke to the morning. The owl walked back into his nest in the hollow-of-a-tree, and he proceeded to do his morning ritual: He made himself a cup of cocoa and he climbed into his cozy chair with his book—but not before he had taken the postcard and attached it to a little twig that had ingrown just above the fireplace. And there he continued to look at the strange structure until he drifted off to sleep.

When he awoke, he knew what he had to do.

That night, rather than standing on the branch, as he had for so many nights prior, he instead began flying around the neighboring trees, retrieving branches and twigs in his talons. Once he’d amassed a nice pile at the base of his broken tree, he began to select the straightest and the strongest of these branches.

He then began to build.

Using the picture as a rough template, the owl, in the dark of night, began assembling the tower’s four legs. They each collapsed a few times, that first night, before he was finally able to get one to stand firmly. From that, he guessed that the little maple branches he’d salvaged were best for the job, and once he’d built a strong enough foundation, he fortified the legs by weaving dogwood twigs through the branches, which also managed to fabricate the latticed look of the tower he was modeling. Before he knew it, the sun was rising and the songbirds were chirping, and he settled back in his hollow-of-a-tree for the night, staring at the tower on the postcard until he drifted off to sleep.

And so his life continued, for some time, night in and night out, as he collected scavenged forest debris and used it as building blocks for a scale model of the incredible edifice on the postcard he carried with him wherever he went, a structure that the owl believed to be a testament to the dynamic thinking and ambition of organic life. The squirrel had mentioned that he believed it was his fellow species that had built the original; the owl now suspected that his own, Strix varia, had been responsible for this particular feat. He was intent on re-creating it.

It happened, after many months had passed, that the owl finally came close to finishing his laborious endeavor. The neighboring forest floor had been largely picked over in his pursuit, and he found he often had to go farther afield to source the right building materials; some miles off, he’d found a green pinecone, perfectly conical in shape, that would serve perfectly as the final piece, the pinnacle of the tower’s top. That night he intended to set it.

And set it he did, in a moment that seized his little owl heart and gave him such an electricity that he could barely keep his talons from quivering as he laid the pinecone at the apex of the latticed tower. Seeing it affixed, the owl flew back to his perch on the branch on the broken tree and looked down on his creation with pride.

Just then, the owl heard a noise. It was a kind of rumbling noise, coming from somewhere distant, and it seemed to unsettle the forest in its growlings. The greenery rustled and the birds whistled in alarm; within seconds, it rolled into the small clearing below the owl’s hollow-of-a-tree: a kind of bulbous wave, echoing out from some far-off point, in the vegetation itself. He saw it coming several yards away, creating a weird roll to the landscape, but could barely dive down to his creation before the wave had come upon him.

It bucked the wooden tower and caused it to sway, dangerously, in the wake. The pinecone, so recently affixed, began to topple from its perch and the owl swooped down, in a panic, to catch it. But no sooner had he saved the cone from falling than the rest of the structure began to tremble and snap. Seized with terror that his beloved creation was about to come tumbling down, the owl desperately flew about the tower, bracing all the struts and supports that were threatening to break apart. Seconds passed like hours. Time seemed to still to a stop. Finally, the owl, his one talon braced on one of the legs of the tower, his other talon somehow extended to the midsection, felt the structure settle back into place, and he breathed a long and very exasperated sigh.

Two men, one fairly dragging the other along, suddenly entered the clearing and, their eyes trained behind them, ran headlong into the owl’s creation and knocked it, every maple branch and every twig of dogwood, to the ground in a splintering crash.

The owl fell backward, devastated.

The two men seemed to not even have reckoned what damage they’d done, as they were gone from the clearing within the bat of a wing.

The forest floor lay littered with little scavenged sticks; a single pinecone rolled to a stop at the base of the owl’s broken tree. And then, some moments after, adding insult to injury, a group of kids came charging through the clearing and sent the piled remains of the tower cracking and spinning into the surrounding bracken.

The owl put his wing to his brow and sighed.

When the fog and smoke had cleared and the trees seemingly materialized on the horizon before them, as if conjured, Elsie immediately knew where the man was taking Carol. Inwardly, she knew that her path, and her sister’s, would eventually lead back into the Impassable Wilderness. She just hadn’t anticipated it quite happening like this. Once they’d come to the end of the barren, scrubby skirt of land that served as a sort of buffer between these two I.W.s, they knew what to do.

“Nico,” shouted Rachel. “Grab hands!”

“What?” called the saboteur, his breath labored from the pursuit.

“Just do it!” called Elsie from the front of the pack.

The group locked hands, with Nico in the center and Rachel taking up the rear. They recalled how they’d left the Periphery, so many months ago; they could only hope that the enchantment remained.

They heard a shout from behind them; jerking her head around, Elsie saw that the sound had erupted from an enraged mob of stevedores, some two dozen in number, that were steaming toward them at full speed. The burning remnants of Titan Tower smoldered behind them.

“Quick!” yelled Elsie. Mindful to keep a tight grip on the hand of the soul behind her—who happened to be Oz—Elsie led the troupe beyond the veil of trees and into the forest. The rumble and yell of the stevedores grew louder; they were getting closer.

Rachel, being the last in the line, glanced back at their pursuers just as they crossed over; the hulking shapes of the stevedores seemed to blur and shimmy in the dim light until they disappeared completely. Perhaps she saw a single maroon beanie fall to the ground behind her, or perhaps it was just a trick of the light.

The woods surrounded them. The trees seemed, in a way, to swallow them whole.

A rustle from ahead, a strangled shout, alerted them to Roger and Carol’s trail; they pressed on, stepping through the knee-deep vegetation. Once they were certain they’d crossed far enough, they unlocked hands. Nico retrieved a flashlight from his knapsack and stepped up to the front of the pack. He and Elsie, together, led the team forward, ever watchful of the ground at their feet and of the path of disturbed undergrowth that the two men ahead of them left in their wake.

“Carol!” shouted Elsie when they’d taken a wrong turn.

A holler came from their right; it was immediately choked off.

“This way!” shouted Nico.

The forest crowded around them, hampering their every step. The dark spaces in between the trees loomed menacingly, and Elsie thought she heard strange rattlings in the underbrush. She kept her eye trained on the bouncing ray of Nico’s flashlight as if it were a rope and she was dangling from a cliff. She feared that were she to leave the safety of the light’s bare glow, she would be lost forever in a wood that felt more inhospitable and more threatening with every step they took.

A light danced off the branches ahead of them, giving away Roger and Carol’s location; they were making their way up a steep slope some ten yards distant. The children and Nico had no sooner seen the two men, however, than the light disappeared and the two were gone again, deep into the bushes. They followed the path, scrambling up the hill and through a dense clutch of ivy vines. They tore through a small clearing, their feet trundling over what looked to be a massive stockpile of sticks and branches scattered about the forest floor; Elsie looked down at this in horror, briefly, wondering at the sort of obsessed animal that would make such a bizarre collection as this. They’d already gone farther, she guessed, than she’d ever ventured before into the Impassable Wilderness.

They’d grown close enough now that they could hear the two men as they crashed their way through the trees; Nico stopped the rest of the Unadoptables with a wave of his hand as if to say, Listen.

They stopped. Silence. It was evident that the two men, Carol and Roger, had paused in their escape.

“Mr. Swindon!” shouted Elsie. This was the name Desdemona had used describing the man; she guessed it was the same gentleman who had initially demanded Carol be delivered to him, back when they’d had the standoff with the stevedores during the orphanage rebellion. It was a hunch, anyway.

“How did you . . . ,” came the shout in response. “Who are you?” It was the voice of a fatigued and very confused man.

“We want Carol back, that’s all!”

“Well, you can’t have him!” was the response. Then: the two men’s noisy retreat started up again.

The six Unadoptables and Nico continued their pursuit.

The forest here felt older, more ancient. The tree trunks they rounded were the heft of midsize automobiles, and the fern glades they stumbled through looked straight out of some computer-generated cut-scene from a dinosaur documentary. Elsie felt her attention being drawn in a million different directions. Her eyes were fixated on the way ahead, the bouncing glow of Nico’s flashlight and the sound of the two men’s shambolic running in the distance; her heart and her mind were constantly being drawn to the crowding forest, to the sounds that sparked in the night, strange and alive.

Nico screamed, once, suddenly.

“What is it?” shouted Rachel from behind.

“There’s creatures! In the woods!” he shouted frantically as they ran.

Elsie took her eyes off the way ahead and scanned the nearby bushes; she saw it too: A head appeared, a bulky torso. “Run!” she shouted. “Faster!” Spikes of fear shot through her limbs, and she charged forward.

Their pace quickened; still, they saw the figures in the trees, as if silently watching them, following them.

Just then, they heard a shout sound from the trees ahead: It was Carol and Roger, their voices united in a single, surprised exclamation. A great crash followed the sound quickly, and the trees ahead were seen to shake wildly.

Nico aimed the flashlight dead ahead, and they followed the two older men’s path through a thick stand of salmonberry stalks to arrive at a small and very empty clearing. The surrounding bushes seemed undisturbed; it seemed as if the two men had simply entered the clearing and disappeared completely. Nico shone his flashlight wildly in every direction, trying to puzzle out where the two men had vanished; the beam fell on a figure, his face darkened, between two tree trunks.

Ruthie and Oz yelled, simultaneously. Nico wheeled the flashlight to the other side of the clearing to reveal another looming, darkened figure, watching them silently from behind an ivy-covered stump.

“Who are you?” shouted Rachel. “What do you want?”

Elsie stepped forward, having seen another figure in the near dark. There was something vaguely strange about him, she decided. Before she was able to get a clear view, a small click sounded below her feet. She looked down, just in time to see the world erupt from beneath her toes and carry her skyward.

It had happened too quickly, really, for anyone to reckon exactly what had transpired. By their minds, the six Unadoptables and Nico, they had simply been standing in the middle of the clearing, seemingly surrounded by mysterious, silent watchers, when, the very next moment, they were dangling an easy thirty feet above the forest floor. All they’d heard was a wheezy creak, a snap of a branch, and they’d been conveyed thus, heavenward, dangling in the ether. A quick catalog of their situation revealed that they were in some sort of net, woven from very organic-looking material, a net that had bagged the six of them as if they were the evening’s groceries. What’s more: A survey of the surroundings alerted them to the presence of both Mr. Swindon and Carol, who were swinging in a similar webbed container, not ten feet away from them. Jumbled together like action figures in a pillowcase, the captured seven had been forcibly entwined, and Elsie felt Harry’s elbow locked around her fibula; the surprised face of her sister was dangling directly above her, and the girl’s long black hair was draping into Elsie’s mouth. They all groaned, as one, as they tried desperately to unlock themselves from one another, still in shock from their sudden change of circumstance. Elsie, her face pressed to the mesh of the net, looked down on the mysterious figures that had surrounded them, waiting for them to approach and claim their quarry.

A groaning could be heard from the opposite net. Martha cried out, “Carol! Are you okay?”

“I’m okay, dear heart,” came Carol’s voice. “Just a little bruised up is all.”

“Quiet, old man,” shouted Mr. Swindon.

“Why?” Carol was heard to say. “What are you going to do? Gnaw my arm off?”

From the looks of it, the net that had captured Carol and Roger Swindon had cinched very tightly, owing to the lesser cargo, and the two men were immobilized in an unwilling bear hug.

“What happened?” Elsie shouted.

“Was this your doing?” Nico yelled at the opposing net.

“Quiet!” shouted Roger, considerably perturbed. His plan had clearly gone very south, very quickly. He began to mumble to himself loudly; Elsie made out the words “Wigman” and “Bicycle Maiden” and “Wildwood,” interspersed with the sort of swear words one usually hears emanating from grumpy biker gangs.

“As soon as we get down from here,” threatened Nico, “we’re going to give you the what-for, so help me God.”

“We won’t be getting down,” said Roger. “Or at least we won’t be getting down alive. We’re in Wildwood now, kiddies. There’s no telling what baleful souls have captured us.” He laughed an ironic sort of laugh, one that sounded as if it had been steeped in sulfuric acid. “I’d chalk this up to brigands, but the Wildwood bandits are no more. Must be some other desperate, starved creatures. No doubt we’ll all be making some tribe of cannibals a decent meal come morning.”

Elsie shivered at this suggestion. She looked down at the figures surrounding them; she found it strange that they had not advanced or said anything. “Hello?” she called out. “Who are you?”

No answer came. Roger, with some difficulty, moved his head so he could see the ground below. He made a surprised exclamation, having just now seen the silent figures watching them writhe in their nets. “It can’t be!” he shouted. “I wiped you out! I saw to it myself!”

The figures in the darkened patches between the trees gave no response.

“Show yourselves!” shouted Nico, exasperated.

Finally, after some time had passed, the sound of crunching footsteps in the dark alerted them to someone—or something—drawing closer. They all ceased their mutterings and shiftings and trained their eyes into the muddled distance, trying to make out who their captors were. Elsie grasped the vines of the net and stared out, watching carefully, breathlessly, as a humanoid shape emerged from between two wide tree trunks, bathed in the dark. She blinked her eyes rapidly, willing them to grow accustomed to this blackness, lit only by a sliver of a moon (Nico’s flashlight having fallen during the capture; its batteries had spilled out into the blanket of vines on the ground), which cast the forest floor in a dim white sheen. A stand of ferns parted; the form walked through it slowly, a stalking creep, and Elsie’s heart rate began to quicken, her racing imagination set loose to envision whatever horrific creature it chose, bent on whatever terrible, wicked desire her mind could conjure. And suddenly, just as she’d dreamed up the worst possible fate for her and her friends—something that involved a large cast-iron pot, a fish paring knife, and, oddly enough, a kind of reptilian creature with a lightbulb for a head—the glow of the slim moon glinted against a pair of wire-rimmed eyeglasses perched on the figure’s nose, and Elsie let out a gasp.

“Curtis!” she shouted.