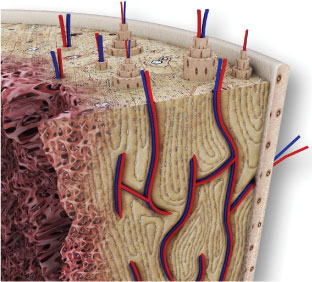

Bone is the dynamic living tissue that forms the body’s structural framework. Bone mass is composed of organic and inorganic materials, including calcium salts and connective tissue, as well as cells and blood vessels within a calcium matrix. This combination gives bone a tensile strength near that of steel, yet it maintains a modicum of elasticity. By aligning the direction of the force of gravity along the major axis of the bones, we can access this strength in Yoga postures.

Regular practice of Yoga is beneficial for your bones because healthy stresses are applied in a variety of unusual directions. This strengthens bones, which remodel in response to stress by depositing layers of calcium into the bone matrix. Like a physiological yin/yang, lack of healthy stress on bones weakens them.

Bones are also the body’s reservoir for calcium, critical in a variety of physiological functions, including muscle contraction. The concentration of calcium in the body is tightly regulated through a complex interplay between the skeletal, endocrine, and excretory systems. This involves feedback loops between the parathyroid gland, the kidneys, the intestines, the skin, the liver, and the bones.

living bone

Bone mass decreases in osteoporosis. This age-related decrease is associated with the loss of estrogen in post-menopausal women. Studies have demonstrated that resistance exercise maintains bone mass. Accordingly, it is reasonable to conclude that the various healthy stresses that Yoga practice applies across the bones may aid in preventing osteoporosis.

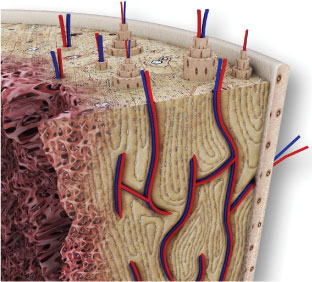

The bones of the skeleton link together at the joints and act as levers for the muscles that cross the joints. Consciously contracting and relaxing these skeletal muscles moves the body into the various Yoga postures.

vertebral body

ilium

femur

calcaneus

Virabhadrasana II

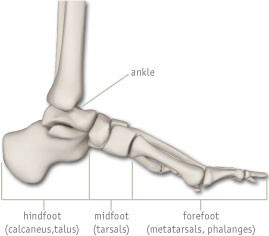

The form or shape of a bone reflects its function. Long bones provide leverage, flat bones provide protection and a place for broad muscles to attach, and short bones provide for weight bearing functions.

Yoga accesses each bone’s particular potential, using the long bones to leverage the body deeper into postures, the flat bones (and their accompanying core muscles) for stability, and the short vertebral bodies to bear weight. Examples of these bones are illustrated here.

The Sanskrit word for a Yoga pose is Asana. Sanskrit scholars variously translate this word to mean “a comfortable or effortless position.” Yoga postures approach effortlessness when we align the long axis of the bones with the direction of gravity. This decreases the muscular force needed to maintain our postures.

For example, in Uttanasana, the force of gravity aligns with the long axis of the femur and tibia bones. Similarly, in Siddhasana the force of gravity aligns with the long axis of the spine.

Use muscular force to bring the bones into a position where they carry the load. Once these positions are attained, muscular force is no longer necessary (or is greatly decreased).

Uttanasana

Siddhasana

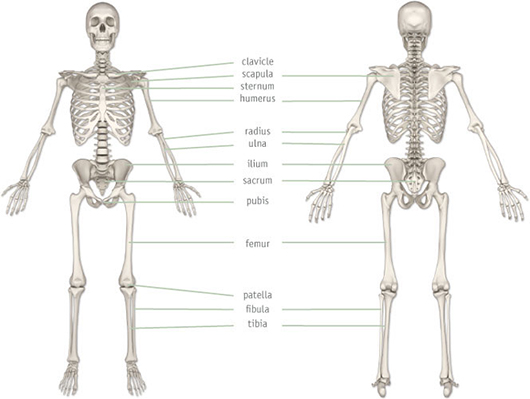

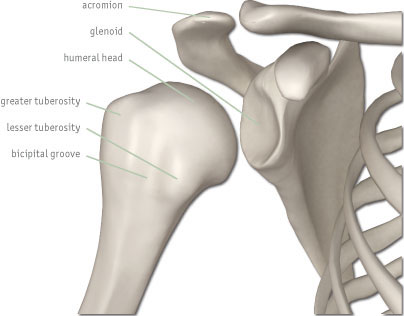

The hips and shoulders are ball and socket joints. Their form reflects their function, in that the deep socket (acetabulum) of the hip is designed to support weight, while the shallow socket (glenoid) of the shoulder is designed to provide maximum range of motion for the arms. Yoga postures balance mobility and stability by increasing the range of motion of the hips and stabilizing the shoulder.

hip

shoulder

axial skeleton

appendicular skeleton

The axial skeleton consists of the spinal column, cranium (skull), and rib cage. The spinal column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, which is the central energy channel, or Sushumna Nadi. It is the axis around which the poses of Yoga revolve. The appendicular skeleton connects us with the world: the lower extremities form our connection to the earth, and the upper extremities, in association with our senses, connect us with each other.

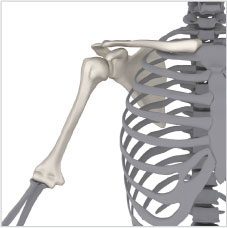

The shoulder girdle is the yoke that connects the upper extremities to the axial skeleton. It is the seat of the brachial plexus, a collection of nerves that, in association with the heart, forms the basis for the fourth and fifth Chakras. The shoulder girdle is comprised of the following structures:

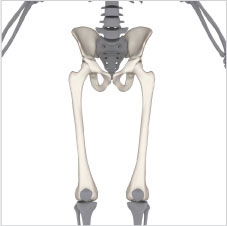

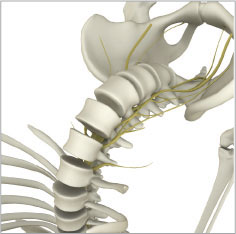

The pelvic girdle is the yoke that connects the lower extremities to the axial skeleton. It is the seat of the sacral plexus, a collection of nerves that forms the basis for the first and second Chakras. The pelvic girdle is comprised of the following structures:

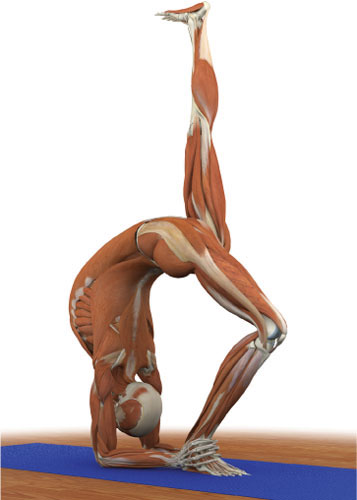

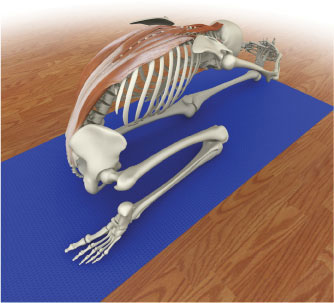

Eka Pada Viparita Dandasana demonstrates connecting the upper and lower appendicular skeletons to create movement in the axial skeleton. Note the inset image demonstrating the stimulation of spinal nerves in this back bend.

nerve roots in a back bend

Eka Pada Viparita Dandasana

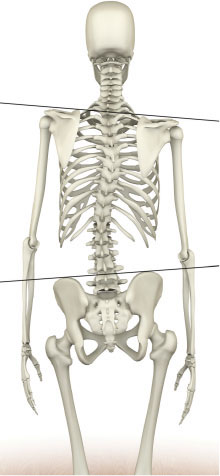

We determine the spinal curves by viewing them from the side. Kyphosis is a convex curve and lordosis is a concave curve.

This illustration demonstrates the four normal curves in the spine:

1) cervical lordosis

2) thoracic kyphosis

3) lumbar lordosis

4) sacral kyphosis

Tadasana

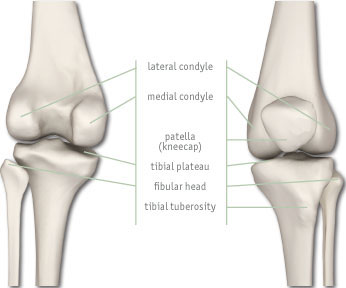

Scoliosis is a lateral deviation and rotational deformity of the spine. The most common form of scoliosis is called “idiopathic,” meaning without an identifiable cause. Other forms include congenital and neuromuscular scoliosis. Studies have suggested that idiopathic scoliosis is related to hormonal factors, including the level of melatonin produced. This form of scoliosis also has a hereditary component.

When the magnitude of the scoliotic curve progresses beyond 20 degrees, there is a risk of continued progression after skeletal maturity. Very large scoliotic curves can impact respiration by restricting the ribcage.

Scoliosis also affects the pelvic and shoulder girdles, as illustrated here. For example, tilting the pelvic girdle creates a perception of limb length discrepancy (one leg shorter than the other). Similarly, one arm may appear shorter than the other.

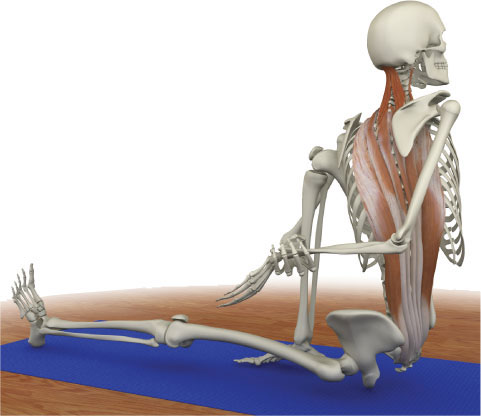

Scoliosis affects the bone, cartilage, and muscles of the spine. Muscles on the convex side of a curve become chronically shortened when compared with those on the concave side. Yoga postures aid to counteract this process by stretching the shortened muscles.

scoliosis

Marichyasana

These images of a twist, back bend, and forward bend demonstrate how Yoga postures contract and stretch the back muscles. This lengthens chronically shortened muscles on the concave side of the scoliotic curve while strengthening them on the convex side. This assists in balancing perceived discrepancies in limb length and may also improve nerve conduction.

Salabhasana

Trianga Mukhaikapada Paschimottanasana