A cultivated man of middle age recounts the story of his coup de foudre. It all starts when, travelling abroad, he takes a room as a lodger. The moment he sees the daughter of the house, he is lost. She is very young, but her charms instantly enslave him. Heedless of her tender age, he becomes intimate with her. In the end she dies, and the narrator – marked by her for ever – remains alone. The name of the girl supplies the title of the story: ‘Lolita.’ It is the ninth of the fifteen tales in the collection The Accursed Gioconda, and it appeared forty years before its famous homonym.10

On reading it today and comparing it with the novel which fortunately was not burnt, a slight feeling of unreality and déjàvu comes over us – as if we had entered one of the labyrinthine stories of Borges. The core of the tale depicts a journey to Spain. The anonymous first-person narrator sets off from South Germany, after bidding farewell to a pair of elderly brothers who own a tavern that he frequents. For reasons that remain unclear, they react strangely to the announcement of his trip. The narrator travels through Paris and Madrid to Alicante, where he takes lodgings in a pension by the sea. He plans no more than a quiet holiday. But then, after a brief delay, comes that first fatal glance, which cannot but remind us of the later Lolita. There the first-person narrator, Humbert Humbert, makes a journey with the intention of finding a quiet place to work near a lake – surrogate of an Ur-scene by sea. In the little town of Ramsdale he calls on the landlady, Charlotte Haze, whom he finds as unattractive as her residence. Inwardly resolved to leave, he follows Mrs Haze as she conducts him through it:

I was still walking behind Mrs. Haze through the dining room when, beyond it, there came a sudden burst of greenery – ‘the piazza’, sang out my leader, and then, without the least warning, a blue sea-wave swelled under my heart and, from a mat in a pool of sun, half-naked, kneeling, turning about on her knees, there was my Riviera love peering at me over dark glasses.

It was the same child – the same frail, honey-hued shoulders, the same silky supple back, the same chestnut head of hair.11

This one glance is enough, and Humbert Humbert stays. So too for Lichberg’s first-person narrator, just as the beauty of his young girl also has a dark underside in a mystery of the past:

‘The friendly, talkative landlord gave me a room with a wonderful view of the sea, and nothing stood in the way of my enjoying some weeks of undisturbed beauty.

‘Until, on the second day, I saw Lolita, Severo’s daughter.

‘By our northern standards she was terribly young, with veiled southern eyes and hair of an unusual reddish gold. Her body was boyishly slim and supple, and her voice full and dark. But there was something more than her beauty that attracted me – there was a strange mystery about her that often troubled me on those moonlit nights.’

Like Humbert, our narrator is immediately bewitched, and abandons any thought of departure. His Lolita too, like Dolores Haze later, is subject to violent changes of mood. Does she want something from him or not; is she hiding secrets in her child’s breast? As in the case of the agreeably surprised Humbert Humbert, it is eventually Lolita who seduces the narrator, not the other way round. The author does not say so outright (we are still in the Kaiserreich), but his ellipses and circumlocutions leave the reader in little doubt of the amorous realities:

‘There were days when Lolita’s big shy eyes regarded me with an unspoken question, and there were evenings when I saw her burst into sudden uncontrollable sobs.

‘I had ceased to think of travelling on. I was entranced by the South – and Lolita. Golden hot days and silvery melancholy nights.

‘And then came the evening of unforgettable reality and dreamlike magic as Lolita sat on my balcony and sang softly, as she often did. But this time she came to me with halting steps on the landing, the guitar discarded precipitously on the floor. And while her eyes sought out the image of the flickering moon in the water, like a pleading child she flung her trembling little arms around my neck, leant her head on my chest, and began sobbing. There were tears in her eyes, but her sweet mouth was laughing. The miracle had happened. “You are so strong,” she whispered.

‘Days and nights came and went …’

That is both as inexplicit, and as unambiguous, as befits the period. The days and nights devoted by a lover to the sweet mouth of a lovely nymphet became sexually indecent only with Nabokov, who at first thought of publishing his manuscript anonymously, and later only just escaped the Old Bailey. The correspondence of core plot, narrative perspective, choice of name and title is none the less striking. Unfortunately, as Van Veen remarks in Ada, there is no logical law that would tell us when a given number of coincidences ceases to be accidental.12 In its absence, it is not easy to answer – but, of course, even more difficult to dismiss – the unavoidable question: can Vladimir Nabokov, the author of an imperishable Lolita, the proud black swan of modern fiction, have known of the ugly duckling that was its precursor? Could he have been affected by it?

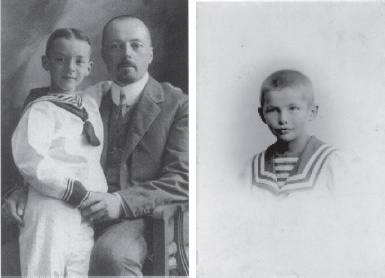

The path of the author, at any rate, he could easily have crossed. Heinz von Lichberg lived in the southwest of Berlin, as did Nabokov. As a child, Nabokov had often stopped in Berlin when his family was en route to France. A year after the family fled from Russia, in 1919, his parents and siblings moved to the Grunewald district of the city, where Vladimir visited them during his vacations from Trinity College, Cambridge, where he read Slavic and Romance languages. In March 1922 his father, a prominent liberal politician and publicist, was assassinated in the Berlin Philharmonic Theatre by a Russian monarchist. That summer Vladimir moved from England to Berlin, and – he least of anyone would have expected this – stayed there until 1937. In these fifteen Berlin years he got to know Véra Slonim, and married her; became the father of a son; and, under the pen name Sirin, became the outstanding Russian writer of the younger generation. There he wrote no fewer than eight Russian novels, and had almost finished the ninth and greatest, The Gift, when he began The Real Life of Sebastian Knight and, with it, his conquest of American literature.

None of which yet tells us whether Sirin–Nabokov could even have read the German ‘Lolita’. The question, like so many others among Nabokovians, is disputed. So far as his knowledge of matters German went, Nabokov always remained reticent, if not in denial. He let it be understood that, cocooning himself in the Russian exile community for fear of losing his mother tongue, he scarcely spoke any German, and read no German books. His German translator and editor, Dieter E. Zimmer, holds this repeated assertion to be ‘objectively somewhat exaggerated, but subjectively the simple truth’.13 Perhaps subjectively it was true, but objectively somewhat over- (or under-) stated. Nabokov indeed never mastered German – which he had learnt at school14 – anything like as well as English or French. But he was not lying when he asserted ‘a fair knowledge of German’ in his application for a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1947.15 Nor was it an untruth when he wrote to Princeton University Press in 1975 that he read German, but couldn’t write in it.16 Nabokov’s antipathy towards the Germans as a people – which later grew into real detestation17 – did not prevent his ‘fair knowledge’ of their language extending to their letters. Not only was he familiar with the German Romantics and classics.18 He treasured Hofmannsthal, honoured Kafka, whose translation into English he improved, and despised Thomas Mann (whom he studied with the aid of a dictionary). Of Freud, he remarked that one should read him in the original, which we must therefore presume he had done.19 The awful first German translation of Bend Sinister made him write to the publisher that it would cost him more time and labour to iron out all its howlers than a new translation would involve.20 As translator himself, he brought various poems by Heine and the ‘dedication’ from Goethe’s Faust into Russian. His opinion of contemporary German literature was low, but plainly not just based on prejudice. In The Gift (which also alludes to Simplicissimus, where Lichberg had once published poems) he mentions works by Emil Ludwig and the two Zweigs disparagingly, and in one of his stories he took a little sideswipe at Leonhard Frank’s novel Bruder und Schwester – after, we must hope, having read it.21

Someone who knew of Leonhard Frank’s incest novel could in principle also have run across a Lolita story by Heinz von Lichberg. Not as a novelist, but as a feuilletonist and travelling reporter for the Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger, Lichberg was permanently present during the fifteen years that Nabokov lived in the city. Assuming, then, that by one of those coincidences in which life is richer than any novel should be, the Gioconda book fell into his hands: what could have prompted him to leaf through it? A false gleam in its title, perhaps. Lichberg’s collection of tales appears to be about Leonardo’s Mona Lisa. That could have caught the eye of Nabokov, who was an admirer of Da Vinci. In 1940 Nabokov invoked the shining figure of Leonardo as an example of true human greatness, placing him, as the antithesis of Hitler, on the most glorious of all pedestals.22 Perhaps in his late twenties or early thirties Nabokov, who might have been interested in the spectacular theft of the Gioconda from the Louvre in 1911, picked up a book that promised to reveal her secrets. Lichberg’s title story was not in fact about Leonardo’s Gioconda, but an indifferent figure of the same name. This was something, however, that could be learnt only after opening the book. If one did so, the eye might have been caught by the silhouette of a very young girl – assuming that the theme had a certain allure.