CHAPTER 3 RELIGIOUS INDIA

‘[The caste hierarchy is] an ascending scale of hatred and a descending scale of contempt.’

Dr Bimrao Ambedkar

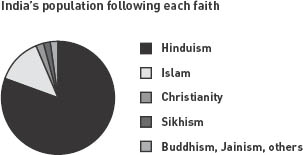

AT THE HEART of Hindu religion, the religion of four out of five Indians, is the concept of dharma. This, very simply put, is one’s duty in life, and one achieves it, essentially, by performing actions (karma). Unlike Christians, though, who all follow the same moral code, the Hindu’s dharma is a many layered word. Indeed, it could be defined more as a way of life than just an obligation to do the right thing. Your dharma changes as you go through different stages of your life, and it varies from person to person. What is one person’s dharma is not another’s – and what is one group’s dharma is not another’s. It is this group dharma that underpins the Hindu caste system and, since 85 per cent of Indians are Hindu, ensures the caste system dominates Indian life.

Source: The First Report on Religion: Census of India, 2001

One of the world’s oldest religions, Hinduism dates back at least three thousand years to the time of the Aryans who began to people India during the second millennium BCE. It has no founder, prophet or single creed like other major religions but encompasses a vast panoply of gods and goddesses, cults and practices – some universally known, some adopted by just a handful of villages. Indeed, Hindu is both a prescriptive religion and an extraordinarily adaptable one, constantly absorbing new deities and philosophies, so that the practice of the religion varies in a way that would be impossible in Christianity.

* Females per 1000 males

The Vedas

Much of the religion’s law, however, comes from four sacred texts known as the Vedas, written between 1000 BCE and 500 CE. One of the central tenets is the idea of reincarnation. The life to which you are reborn depends on how well you performed your karma. According to the Upanishads, the appendix to the Vedas, you could be reborn ‘as a worm, or as a butterfly, or as a fish, or as a lion … or as a person, or some other being in this or that condition’. To be reborn in a better form, you must live according to your dharma. If you don’t, you’re sure to slip down the levels of life. If you do live well, however, you gradually ascend the ladder so far that you achieve moksha – a perfect state of knowledge and happiness in which you are liberated from the cycles of rebirth and merge with Brahman, who/which can be seen as the One God, or as a kind of universal consciousness. The Upanishads describe Brahman as

That from which beings are born,

that by which, when born, they live,

that into which, when dying, they enter.

Sacrifice is central to dharma – not just gifts to the gods, but metaphorical sacrifices of the baser aspects of your individual nature. By sacrificing that damaging individuality, you help your soul to merge with Brahman. It is not surprising then that Hindus place strong emphasis on community or caste loyalty – and it is not surprising that they tend to accept their lot in life, since to challenge it would be to abandon their dharma and guarantee that their next life would be worse.

HINDU GODS

Hindus are not mean when it comes to including different gods and goddesses. Indeed, it is often said that there are 330,000 of them in their pantheon. This bewildering variety doesn’t mean that Hindus believe that gods and goddesses are almost as numerous as people. They actually believe in the Brahman, the one god, and all these myriad deities are essentially different forms of Brahman. But the variety allows Hindus to make their relationship with the gods far more personalised and intimate than is ever dreamed of in Christianity and Islam. There is a well-known story about gopis, the beautiful maidens of the land of Krishna. When a philosopher went on about how elevated it was to think of Brahman and the higher truths, one gopi said. ‘It’s all very well to know Brahman, but can the ultimate reality put its arms around you?’

The three oldest and greatest of the Hindu gods, Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva, create a perfectly balanced triangle of creation, preservation and destruction. Brahma is the creator who set the universe in motion. He is usually shown with four heads, each reciting one of the Vedas. Vishnu is the preserver and arrives on earth as an avatar (incarnation) whenever humankind needs help. He traditionally appears riding the mythical bird, the Garuda, dressed in dark blue, and with four arms pointing out the four points of the compass. Shiva is the destroyer, who often appears covered with writhing snakes and smeared with ashes, dancing the tandava, the dance of destruction. But Shiva’s destruction is necessary and positive; it cleanses the world of impurities.

Each of these three gods has consort goddesses. Brahma’s consort is Sarasvati, the goddess of learning. Vishnu has Bhudevi, the earth goddess, and Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth, prosperity and fertility. Shiva has a range of consorts, who each embody the female principle or shakti, including Parvati who appears as Uma the golden goddess, angry ten-armed Durga and the bloodthirsty Kali, sometimes called the goddess of death. Shiva and Parvati had two sons including the jolly, wise and thoughtful elephant-headed god Ganesh.

Rama is one of the various avatars of Vishnu. He became the hero of the Vedic epic the Ramayana in which he conquers the world’s most powerful demon, the ten-headed Ravana, who has kidnapped Lakshmi’s avatar Sita. In this epic, Hanuman the monkey god helps rescue Sita. Among the many other Hindu gods are Agni the god of fire (who gave a name to India’s first nuclear missile), Varuna the god of rain and Yama the god of death.

PROFILE: SRI SRI RAVI SHANKAR

In 2006, an Indian spiritual leader called Sri Sri Ravi Shankar was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by US congressman Joseph Crowley, who described and the work of his Bangalore-based Art of Living Foundation as ‘an example of communal conflict resolution, nourishment of the soul and infinite possibilities of the human spirit which typifies the Nobel Peace Prize’. He didn’t win, but his role in trying to negotiate a settlement between opposing sides in Sri Lanka has been acknowledged.

Sri Sri Ravi Shankar is the most famous of a new breed of spiritual leaders in India who are appealing particularly to the young. In his book In Spite of the Gods, Edward Luce describes Shankar in person as looking like ‘Jesus Christ in a shampoo advert’ with his long flowing locks and beard and his white robes. Some liken him to the Christian TV evangelists of the USA with his media-savvy approach. But Shankar’s mild personal manner couldn’t be more different. He says he is not an evangelist at all: ‘Why do people want to convert to other religions? … We should protect the cultural diversity of the planet and not try to change it.’ Shankar’s message has clearly struck a chord with those of various castes who are making a new life in India’s boom industries and find they have little accord with traditional caste-dominated Hindu religion. His calm vision seems the perfect antidote to the stress and confusion of high-tech, consumer living. It is this, more than the RSS’s ‘muscular’ monolithic Hindu-power that seems more akin with young India, at least in the cities. Not surprisingly, perhaps, Shankar’s Art of Living Foundation in southern India has attracted generous funding from the software companies in nearby Bangalore, enabling it to build a striking modern meditation centre, adorned by 1,008 beautifully carved marble lotus petals, and rooms full of LCD lights. Generous support has also allowed the foundation to spread the message and offer humanitarian programmes in more than 140 countries, including war zones such as Iraq.

Dividing society

It is this whole concept of group duty and dharma that lies behind India’s caste system. The idea of reincarnation and dharma led to the idea that people are born into a particular class because of how they lived their previous life. Each class has its own dharma, and those who faithfully live their class dharma hope to be reborn in a higher class. The system emerged from the natural division of labour in Aryan society, into priests, rulers and warriors, farmers and merchants, servants and labourers, and these divisions have become codified over the centuries into castes. Hindus visualised society as a body, in which each of the classes had its place – with the upper classes in the head and the lower classes at the foot.

A hymn in the Rig Veda, the most ancient of the Vedic texts, describes how the caste system was created by the gods from the first man:

What did his mouth become? What his arms?

What are his legs called? What his feet?

His mouth became the priests;

his arms became the warrior-prince;

his legs the common mad who plies his trade.

The lowly serf was born from his feet.

HINDU TEMPLES

The first Hindu temples were built out of wood, and none survive, but in the times of the Gupta emperors (320–650 CE), they began to build hundreds out of stone and a few of these are still standing, including the stunning Deogarh temple in northern India. One of the most impressive is the stone pyramid temple to the sun god Surya at Konarak near Orissa. Konarak, amazingly, lay buried under sand for centuries until it was rediscovered in the 1920s. It’s famous for its astonishing erotic carvings illustrating the Kama Sutra – Hinduism has never had the same problems combining the carnal with spiritual that western religions have! But the great centre of Hindu religion is Varanasi on the banks of the Ganga, where millions of Hindus bathe from the stone steps or Ghats every year. It is thought that any Hindu who dies in Varanasi achieves instant moksha, which is why so many come here in their last days.

When a new temple is to be built, the priest first draws up a mandala, a pattern that encapsulates the cosmos and provides a guide to the placement of all the rooms. Unlike Christian churches and Muslim mosques, there is no one large central hall, but there is a small inner sanctum. This is the egg from which all life starts and is the dwelling place of the god, marked by a spire or vimana. Water plays a crucial role in Hindu religion, providing purification, so most temples are built near lakes or rivers, or are equipped with a large bath in which the Hindu dips to clean him or herself before worship.

Varnas and jatis

The Vedas gave four main castes or ‘varnas’. At the summit were the Brahmins, the priests and teachers, the only caste permitted to read and write. Next were the Kshatriyas, the warrior class whose dharma was to be the world’s rulers. Below that were the Vaishyas, the farmers and merchants, whose dharma was to look after society’s material needs. The lowest caste was the Sudras, the servants, labourers and craft-workers who performed society’s menial tasks.

Within the four varnas, there are nearly three thousand subgroups called jatis. Just which jati you belonged to depended on who your parents were and what their occupations were. A Sudra might be born into a blacksmith’s jati. His father and grandparents would have been blacksmiths, and the chances are that he would become a blacksmith too. However, even if he never touched an anvil in his life, he would stay in the blacksmith’s jati all his life, and so would his children. Your jati not only determines your career, but the area you live in and even the food you eat. Typically, Hindus, marry within their own jati – those marrying outside risk being ostracised, or worse, though this is changing.

KUMBH MELA

Every three years or so, Hindus gather for a giant festival called a kumbh mela at Prayag (Allahabad), Haridwar, Ujjain and Nashik. The word kumbh means ‘urn’ and the mela means ‘festival’, and the festivals celebrate one of the great Hindu creation myths. After the creation of the world, the gods created gifts that frothed up from the primeval ocean. The most valuable was an urn that contained a nectar that made anyone who drank it immortal. According to the story, the urn was stolen by demons, but Vishnu snatched it back and flew away disguised as a rook, chased by the demons. In his flight, Vishnu either rested in four places, or let fall four drops from the urn in these places, now the site of the kumbh melas.

The greatest of the festivals is the gigantic one at Prayag (Allahabad) – the Maha (Great) Khumb Mela – which happens every twelve years. The 2001 Maha Khumb Mela was the largest religious gathering the world has ever seen with, some say, seventy million people coming together for this extraordinary event. Imagine the entire population of the UK descending on Hyde Park in London and will you have some idea of the scale of the event. All the kumbh melas must take place at river confluences, and the one at Prayag is no exception. For the Maha Kumbh Mela, a gigantic campsite must be set up on the flats between the Yamuna and Ganges Rivers in little more than a month or so after the monsoon has ended and the waters have subsided. It is an amazing operation involving the sinking of scores of wells for drinking water, laying hundreds of miles of pipes, building a dozen or so pontoon bridges across the Ganga, putting down mile upon mile of steel plates to provide roads, and much, much more. The conditions can sometimes be, to say the least, challenging. Yet all these vast millions of people come together for the great day of the festival, with very few problems of crime or even illness. At the 2003 Kumbh Mela at Nashik, 39 pilgrims were crushed to death when a crowd began to move too quickly but this was a rare tragic event.

The ‘polluters’

Beyond all the varnas and jati, beyond the acceptable rungs of society were the unmentionables – the ‘untouchables’ outcast so far that they were not even given a name, and only mentioned in the Vedas as a source of pollution. Because they were thought to be polluting, it was believed that no other caste should have any contact with them, and should never eat food prepared by them. Their lot in society was to perform the tasks no one else would, from cleaning up ‘night-soil’ (human excrement) to tanning leather from the hides of cows that had died naturally.

To westerners, this whole system seems like fuel for revolution, but historians have shown that it was always much more flexible than the texts imply. The status of each jati was constantly shifting, and individuals could often move between jati. Nevertheless, the caste system did inspire resentment, and many Hindus converted to Christianity or Islam or Buddhism to escape it. As early as the twelfth century, Islam led the way for a series of breakaway anti-caste movements known as bhakti, which stressed the equality of all before God. Interestingly, though, these groups were gradually reabsorbed by Hinduism, which time and time again proves itself remarkably malleable despite its apparent rigidity.

The survival of caste

Nevertheless, the lasting power of the Hindu caste system to shape the Indian way of life has been nothing short of astonishing. In no other society have such well-defined social groupings persisted for so long – pretty much three thousand years – nor survived so well the coming of the modern age. Many Indians expected the coming of democracy to finally erode the barriers. After all, universal suffrage made every voter equal. Yet in some ways, caste seems to be more entrenched than ever as the decline of the Congress party’s domination of politics over the last fifteen years has allowed countless scores of entirely caste-based parties and vote banks to emerge.

Yet there have been changes – especially in the cities, where the close mixing of people has enforced changes. Necessity and the opportunities provided by economic development have meant people are beginning to seek and get jobs outside their traditional caste base – and of course there are many new jobs that just don’t fit into the traditional mould. IT work in particular mixes people from different castes in a way that would have been unimaginable just thirty years ago. Even caste intermarriages are on the rise. And there is one element of the caste system that really has begun to shift – the position of the untouchables, the caste that is not a caste.

The downtrodden

For a start, they are no longer called untouchables, a term which is thought offensive. They are now mostly called Dalits. Mahatma Gandhi called them the ‘harijan’, the children of god, in an attempt to raise their status, but this is now thought of as rather patronising. The word Dalit, which means ‘the oppressed’ or ‘the downtrodden’, was coined by Dr Bimrao Ambedkar and was made popular in the 1970s by the acitivist group the Dalit Panthers who styled themselves on the American Black Panthers.

Although little known outside India, Ambedkar was, with Nehru and Gandhi, one of the three architects of Indian independence, and it was he, more than anyone, who was responsible for the Indian constitution. Remarkably, he was a Dalit himself, and it was his determination that the coming of democracy would end the oppression of Dalits. He even engineered a clause in the constitution called the Reservation System – a forerunner of positive discrimination – that ensured a certain number of jobs in government and places at colleges were given to Dalits.

MAHARASHTRA RIOTS

Intercaste violence is a common occurrence in India, but the horrific murder of four members of Bhotmange family on 29 September 2005 struck a nerve. The Bhotmanges were Dalits, but they were not a typical Dalit family. They were Mahars, who have always been a more successful Dalit caste. Dr Ambedkar was a Mahar and the Mahars have made particular progress in recent years. The Bhotmanges, though poor, were doing especially well. The 17-year-old Priyanka Bhotmange had graduated from high school at the top of her class and had a bright future ahead of her. Such aspirations clearly angered the Kunbi caste, still poor but a proper caste, not Dalit. Worse still, Mrs Surekha Bhotmange and Priyanka had dared to identify in court those responsible for beating up a relative who had been campaigning to protect their land. On the evening after the court case, an angry mob, who may or may not have been Kunbis, descended on the Bhotmanges’ hut. They stripped Surekha, Priyanka and her two sons and ordered the sons to rape their sister and mother. When they refused to do this, the family was whipped towards the village square. There the boys were hacked to death with axes and the women gang-raped, killed and dumped in a canal.

As the local police tried to cover the affair up, Dalit youth began to start a protest campaign to get justice. The state police started to move against activists to quell the campaign. Then on 28 November, a statue of Ambedkar was beheaded in the city of Kanpur in Uttar Pradesh. Although Kanpur is far away from Maharashtra in the north, the incident provided the spark that started a conflagration down south. Over the next two days, Dalit riots began to erupt all across Maharashtra, most dramatically in Mumbai, where hundreds of buses were pelted with stones and a group of Dalit youths stopped the elite Deccan Queen train, a symbol of upper-caste luxury, asked the passengers to get out then set alight to it.

The Indian government was worried. This was the first time Dalit youth had ever really taken to the streets in protest like this and it was likened by some to the riots of poor immigrant youth in France in 2005. Sonia Gandhi immediately stepped in and met Mr Bhotmange who had been out in the fields when the mob reached his family and assured him that his family’s killers would be brought to justice. Meanwhile, Kanpur police arrested a Dalit youth who admitted to damaging the statue when drunk. Some Dalits in Kanpur alleged that the youth had been framed and started protesting in the streets of Kanpur. The riots eventually died down, but some people wonder if this rebellion of Dalit youth is a significant new development.

Reserved jobs

About 8 per cent of the seats in national and state parliaments are reserved for what are called ‘Scheduled Caste and Tribal’ candidates. Half of all government jobs are now reserved for three disadvantaged or so-called ‘Backward’ classes – the Dalits, the Adivasis (tribal people), and ‘other Backward classes’ such as the Yadav caste – altogether numbering some four hundred million. These reserved jobs are given not through competition, but simply handed out by caste leaders or sold to the highest bidder.

Nevertheless, the Reservation System has slowly but quietly made a real difference to the way India’s two hundred million-odd Dalits interact with the rest of Indian society. Gradually, other castes have got more and more used to interacting with ‘untouchables’ on a day-to-day basis and many Dalits have used the opportunities to scale the career ladder. India has even had a Dalit president, K.R. Narayanan, elected in July 2002, largely by upper-caste Hindus. But the Reservation System still arouses bitter resentment among some of the higher castes on the one side, and Dalits who do not believe it should be restricted to Hindu Dalits on the other.

Patronage power

Many people now argue that the very success of the scheme is proving an obstacle to the further progress of India’s poor. Getting more reserved jobs in government is now the only real aim of many of India’s low-caste parties, and their politicians get elected or booted out depending on their success in delivering patronage in terms of reserved jobs. Lalu Prasad Yadav, one of the leading Yadav politicians, brought in masses of Yadav votes to help Manmohan Singh’s election victory in 2004. In return he was given the Ministry of Railways – which looks after a massive workforce of 1.5 million people and can offer job patronage on a truly gargantuan scale. Naturally, Lalu is deeply opposed to any rationalisation or redeployment of the labour force – and even more hostile to the idea of privatisation. Indeed, he is campaigning for an extension of the reserved jobs system to private companies. It is this power of patronage that has often ensured that Dalits have tended to vote not for politicians who offer a genuine hope of improving the lot of India’s disadvantaged but for those who promise the best patronage. In fact, proof that you have voted for a particular politician who gets elected actually helps you get a job.

Today, Dr Ambedkar is still held in great reverence by a great many Dalits, but his dream that democracy would bring down the caste system and lift Dalits up to equality with the rest of Indian society has not been delivered. Unlike countries such as the UK, where extension of the vote to all has delivered improvements right across the board, the Dalits seem to have become entrenched, in some ways, in the same intercaste, internecine struggles that characterise all the higher castes. Democracy has created great opportunities for some Dalits, but it has left others way behind. But there are signs that this may be changing, as more and more Dalits begin to move into the towns, make careers and discover more flexible ways of living.

PROFILE: LALU PRASAD YADAV

‘Whenever anyone writes about Bihar, they talk about law and order problems, or they talk about caste violence. That is because we have an upper-caste media in India. Even foreigners are fooled by these things.’

So says Lalu Prasad Yadav, one of India’s most colourful politicians. Lalu is the dominant force in Bihar, India’s poorest, most lawless state. Bihar is the crime and extortion centre of India, with an average of six people a day – typically high-caste schoolchildren – kidnapped and held to ransom. Most people believe that Bihar’s politicians are all too deeply involved in these crime rings. With a real shortage of business sponsorship, politicians simply call in the local mafia don and drum up funding through extortion. A full fifth of the candidates in the 2004 election in Bihar were up on criminal charges, including murder and kidnap – and probably many more had criminal connections. Candidates are only barred from standing if they’ve actually been convicted.

For most of Bihar’s history since Independence, it was in the hands of an upper-caste mafia, and the state was lumbered with some of the worst poverty and social conditions in India. When Lalu Prasad Yadav came to power in 1991, he gave the poor people of Bihar hope. He was, like them, from a so-called ‘Backward’ class, a Yadav son of a poor cattle herder, raised in a mud hut. And he was dynamic, outspoken and witty. The disadvantaged – the Yadavs, the Muslims and the Dalits – got behind his banner of social justice and gave him a landslide victory. As chief minister for Bihar, he proved a popular figure, delighting everyone with his common touch, famed for striding through the streets and clearing traffic with his loud-hailer, and bringing cows into his official residence.

But nothing seemed to change much when Lalu was in power, and it turned out that he was tarred with as big a crime brush as anyone. His cabinet included gangsters wanted for murder and kidnap, and in 1997 Lalu himself was thrown in prison for embezzling billions of rupees of state money. The country was shocked, since Lalu had appeared a champion of social justice. That didn’t stop the irrepressible Lalu, though. He simply ruled from prison by installing his illiterate wife Rabri Devi as chief minister instead. She became nicknamed ‘Rubbery Devi’ because, it was said, she simply rubber-stamped her husband’s decisions from prison.

Lalu emerged from jail after a short spell and simply resumed where he had left off, running (or failing to run) Bihar for another eight years in the same rumbustious way, brushing aside awkward questions from journalists about kidnapped children with a smile and a wag of the finger. Finally, in 2005, a new champion of the Backward castes, Nitish Kumar, saw Lalu voted out of office, with a pledge to do something at last for Bihar. But Kumar, if anything, is said to have more criminal connections than Lalu, and Bihar’s condition has not improved notably since 2005. Lalu still has tremendous support amongst India’s 54 million Yadavs, especially in Bihar, and few doubt he will make a comeback there. In the mean time, though, he has ample compensation in his place in Manmohan Singh’s cabinet as railways minister in the national goverment, striding around in his traditional head cloth and rustic clothes – combined, of course, with spotless white shoes.

Southern progress

Interestingly, while caste divisions are rampant in the heavily populated, but still largely rural north of India, they have softened in the south, in urbanised Tamil Nadu. Tellingly, perhaps, affirmative action in terms of reserved jobs has gone on much longer and gone much deeper here than anywhere else. The reserved job system started in Tamil Nadu way back in the 1920s, long even before Independence, and now almost 70 per cent of government jobs are reserved for the ‘Backward’ sector. As a result, Dalits and higher castes have been working alongside each other here for so long that is barely an issue, and it is perhaps no surprise that Tamil Nadu is better at caring for its disadvantaged than any other Indian state – and it proved remarkably efficient at getting help even to the poorest people hit by the devastating 2004 tsunami.

Nevertheless, despite these changes, most people live their whole lives within the confines of their caste. They live in the same neighbourhoods, marry people from the same caste and vote for a member of the same caste at every election. Often, apparently opposing castes may unite politically to form alliances, but it is usually out of mutual and narrow self-interest – and if the alliance doesn’t deliver, it will be swiftly ditched.

‘SANSKRITISATION’

In England, people might say the working classes are becoming gentrified. In India, democracy and improved economic conditions are bringing ‘Sanskritisation’ to the lower castes. The word Sanskrit of course, refers to the classical language that only the Brahmins could speak and write. Sanskritisation describes the trend for lower castes to adopt upper-caste habits and lifestyles – worshipping the same gods, going to the same festivals, wearing the same clothes, decorating their houses in the same way and so on. In the past, it was easy to tell a Hindu’s caste from the way he dressed or the look of his home. Now, in cities in particular, it is becoming harder and harder to tell. Only in their voting habits do the lower castes stick firmly to their castes, in order to help them on their way up the ladder.

Islam

Hindu fundamentalists argue vociferously that Islam is a foreign religion implanted in Indian soil, and has no place in India. But Islam came to India almost as early as Christianity came to Britain, and Muslims and Hindus have been living alongside each other here for more than a thousand years. Muslims in India are as Indian as Hindus. They speak the same language, eat much the same food, watch the same TV and share the same cities and villages. Although there are some areas of India that have higher concentrations of Muslims than others, Muslims are spread throughout the country, living side by side with Hindus. Only in Jammu and Kashmir are they in a majority, although they make up a significant proportion of the population in Assam, West Bengal, Kerala and Uttar Pradesh. In other words, they coexist with Hindus pretty much all over India.

Muslims are a minority, but it is a substantial minority. In fact there are 120 million Muslims in India – more than in any other country in the world apart from Indonesia, more even than Pakistan. That they are a part of India as much as Hindus was clear to Nehru from the start, despite Partition, which drove many Muslims to Pakistan. ‘We have a Muslim minority who are so large in numbers that they cannot, even if they want to, go anywhere else. They have got to live in India,’ Nehru wrote to state heads in 1947.

Muslim v Hindu

Tensions between Hindus and Muslims have flared in recent years and incidents such as the destruction of the mosque at Ayodhya and the Gujarat riots of 2002 (see here) have burned all too hotly into public consciousness. Hindu supremacist organisations such as the RSS and parties such as Shiv Sena have touted a vehemently anti-Muslim line. The BJP even achieved their place in the sun in government largely on the back of their anti-Muslim credentials. Yet, interestingly, when it came to the crunch, Indians – Hindu and Muslim – seem to have stepped back somewhat from the brink of confrontation. The Gujarat riots may have been both its peak and its nadir, as support for the extremist parties wavers.

Interestingly, a study in the 1990s of Hindu–Muslim riots showed that they were actually quite rare, except in two Gujarati hotspots – Ahmedabad and Vadodara. Even in the most violence-prone states, riots tend to be confined to just a few extra-volatile centres. Indeed, most Indian Muslims and Hindus get on with their lives together far more peaceably than the blazing headlines and the dreadful history of Partition might suggest.

The Muslim vote

One reason for this may actually be the democratic process. Muslims are large enough in number to have a significant impact on the make-up of government, both at the regional and national level. And politicians know this. To get into power and stay there, they simply cannot afford to ignore the Muslims. Some people expressed surprise when BJP Prime Minister Vajpayee extended a conciliatory hand to Muslims but he was simply being pragmatic.

In Uttar Pradesh, which sends more members to parliament than any other state, one in six voters is Muslim, and their vote has a signficant impact on the range of parties sent to Delhi. Across the country as a whole, Muslims have a major impact on the outcome of the election in 125 constituencies – more than a quarter of the entire Lok Sabha. They may be a minority, but the Muslims are a minority not so much smaller than the Dalits, who are beginning to have a major impact on politics through the ballot box. It is not just the handful of Muslim members of parliament that rely on the Muslim vote, but also many of the major parties. While this is so, there is perhaps a natural brake on the extremities of Hindu fundamentalism taking root.

In his book Being Indian, Pavan Varma points out how Hindus and Muslims often have too many common interests to allow tensions to get too much out of hand. In Lucknow, Hindu traders rely on skilled Muslim workers to supply them with chikan/zardozi embroidery. In Sitapur, Hindus and Muslims work together in the carpet industry. And in Varanasi, Muslims weave the famous Banarasi saris, while Hindus finance the business. During the Gujarat riots, apparently, Hindu and Muslim business leaders took out adverts in the press asking for calm and saying, ‘Gujarat is and will continue to remain business friendly.’

Nevertheless, the Muslim outlook on life is very different from that of the Hindus. In contrast to the vast panoply of gods worshipped by Hindus, Muslims believe in just one, Allah, and they condemn the worship of the idols that are such an integral part of Hindu religion. And of course, they have their own different festivals, and their own dietary restrictions, which, of course, don’t extend to beef, providing it is slaughtered correctly.

Islam’s coming

Islam began in Mecca in the seventh century CE where a young spice merchant called Muhammad began to worry about the consequences of the pursuit of wealth. Retiring to a cave on Mount Hira outside the city to contemplate, Muhammad was assailed by a fiery vision that gave him the final and definitive revelation of God’s will, which he wrote down as the Koran. Coming down from the mountain, Muhammad began to preach his message to abandon the quest for profit and accept Allah, the one god. Muhammad’s message spread like wildfire amongst the poor and downtrodden across the Arab world and, within twenty years, Islam was not just a major religion but a conquering army, which spread through the Middle East, northern Africa and into India with tremendous force.

Very early in its history, Islam was torn apart by a major schism. Muhammad died in 632 leaving no heir – and Muslims were soon bitterly divided over who should be the religion’s leader or caliph – the Arab elite or Muhammad’s son-in-law Ali. Ali stood back from the fray for a while, and the Arab elite provided the caliph. But as the caliph began to enjoy the fruits of conquest rather too much, resentment among the poor exploded and Ali was propelled into the caliphate. Five years later, Ali was assassinated and the Arab elite retook the caliphate to proclaim their rule over the entire Muslim world.

Ever since, there has been an irreconcilable split between the supporters of the Arab caliphate, the Sunni, who see themselves as the true believers carrying the word of Muhammad, and the supporters of Ali, the Shia Ali (brothers of Ali) who reject all the caliphs as usurpers of the prophet’s legacy.

Today, Sunnis are very much in the majority. About 20 million of India’s 145 million Muslims are Shia, while most of the rest are Sunni, though many Sunni follow the mystic path of Sufism, rather than the more zealous Sunni tradition of the Arabs. In India, Shia and Sunni do not seem to be bitterly divided as they are in Iraq, and work together, for instance, on the All India Muslim Personal Law Board (AIMPLB), which, under the Indian constitution, is allowed to devise separate laws for Muslims on matters such as marriage, divorce and inheritance. In the last few years, Shias have begun to complain that their views are not taken into account by the AIMPLB, but this is a legitimate dispute, not a bloody battle.

Islam reaches India

Just how Islam came to India is the subject of bitter dispute. Hindu nationalists support the view, common even among many non-partisan historians, that it arrived by conquest. Muslim armies came to India, it is said, and made converts in a systematic jihad. According to historian Sir Jadunath Sarkar, ‘Every device short of massacre in cold blood was resorted to in order to convert the heathens’. There is no doubt that there were many bloody and violent Muslim raids, such as that of Mahmud of Ghazni, who stormed through northern India looting temples. Muslim Turks invaded in the twelfth century and set themselves up as sultans in Delhi. But other historians point out that Islam made many converts peacefully in India well before the raiders arrived, as Muslim shipbuilders settled on the south coast in the seventh century, for instance. What the historians say matters, of course, to those Hindus who think Islam is an aggressive interloper, and to those who think it is an old and genuine part of the Indian religious fabric.

Sikhs

Sikhism is India’s youngest religion. It originated in the sixteenth century with the first of a series of ten gurus, Guru Nanak (1469–1539) who drew elements from both Hinduism and Islam to create a religion that, like Buddhism, centred on meditation rather than ritual. Nanak preached, like Hindus, that by following their dharma, devotees could free themselves from the endless cycle of rebirth and achieve moksha, union with God. But he believed moksha did not have to wait for an afterlife and ascension of the caste ladder. It was achievable in this life, by every man and woman, no matter what their caste is. No wonder, then, that for many Hindus at the bottom of the pile, Sikhism offered a promise that at least gave them some nearer hope.

Under the Moghul emperors, though, Sikhs were often persecuted and, in 1699, Gobind Singh, the tenth guru, forged them into an armed community that he called the Khalsa, whose calling was to fight oppression, have faith in one god and protect the faith with steel. Their identity was to be defined by the five Ks: kesh (uncut hair), kangha (comb), kirpan (sword), kara (steel wristband) and kachcha (shorts). Instead of caste names, men would be called Singh (‘lion’) and wear the turban; women would be called Kaur (‘lioness’).

Their martial tradition and the demands of some Sikhs, often backed by violent campaigns, for an independent Sikh state in the Punjab called Khalistan, has earned Sikhs the reputation as being dangerous. Things came to a head in the 1980s, as a wild young Sikh leader called Sant Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, at first encouraged by Indira Gandhi to divide Sikhs, launched a terrorist campaign to achieve the realisation of an independent Khalistan. The problem was that he made his base in the Sikhs’ holiest shrine, the great Golden Temple at Amritsar. When the Indian army stormed the temple in June 1984, many lives were lost and the temple was badly damaged. Bhindranwale was killed in the attack and promptly hailed a martyr. Four months later, Indira Gandhi was killed by two of her Sikh bodyguards as she took the morning air in her Delhi garden. In the violence against Sikhs that followed, many government politicians not only turned a blind eye but actually encouraged the violence, and it has taken more than two decades for the wounds to heal. Now, with a Sikh as prime minister in the shape of Manmohan Singh, it seems the worst is over.

Buddhism

Buddhism is one of the few ancient world religions that began with a recognized historical figure, and he lived in India in the sixth century BCE. After his death around 483 BCE, the Buddha was cremated and his ashes distributed to eight stupas (memorial shrines). In the 1960s, Indian graduate student archaeologist Sooryakant Narasinh Chowdhary discovered one of these resting places. In a remote area of western Indiaat Sanchi, Chowdhary found two ancient mounds and he and his team dug in to find the remains of an ancient Buddhist shrine. At the centre was a round stone box containing a tiny gold bottle full of ashes. An inscription confirmed the identity, saying ‘This is the abode of the relics of Dashabala [Buddha]’.

So there is no doubting the reality of this most Indian of religious leaders. The Buddha, which means the ‘Enlightened One’, was an Indian prince called Siddartha Guatama, and he lived in Lumbini, near the border with Nepal. All his life he stayed in India, and it was Indian people who spread his ideas to China and rest of Asia where he is now far more revered than in India.

Strangely, Hindu-pride organisations treat this most Indian religion as a foreign implant. Only two major communities now practise Buddhism in India, namely Dalits and also Tibetans in exile, particularly in Himachal Pradesh, where the Dalai Lama lives. The Dalit group of Buddhists, sometimes called neo-Buddhists, was inspired by Bimrao Ambedkar in the 1950s, when the great Dalit politician turned on his deathbed to a religion that does not recognise caste. ‘No one is an outcaste by birth,’ said the Buddha, ‘nor is anyone a Brahmin by birth.’ Many Dalits, especially among the Mahars of Maharashtra, followed Dr Ambedkar’s example and became Buddhists.

The eightfold path to enlightment

Legend has it that the Buddha began his path to enlightenment when he was 29 and already had a 13-year-old son. The story goes that his chariot driver took him out of the palace for the first time, and there he saw a very sick old man and a corpse. Stunned, he realised he had to leave the palace and find out why such suffering should ever happen. After travelling around India for six years and finding no answers despite listening to every teacher he could find, he sat down under a bodhi tree in Bodhgaya (Bihar) and began to meditate long and quietly. It was during this meditation that he was finally enlightened and realised that all living things are linked together in a chain of cause and effect – and that problems arise when we think of ourselves as separate, so that we are unable to live harmoniously. For the next 45 years until he died, Buddha spent his time teaching what he had found – and in particular that all unhappiness was caused by desire, which could be eliminated by following his eightfold path:

Right understanding (seeing the world as it really is)

Right intentions (kindness and understanding)

Right speech (avoiding lies and gossip)

Right action (not harming living things, not stealing, not indulging in wrong sexual relationships, alcohol or drugs)

Right livelihood (earning a living in a fair and honest way without harming others)

Right effort (knowing what you can do and using just the right amount of effort)

Right mindfulness (being alert to what is going on around you and within you)

Right concentration (applying your mind fully to meditation and everything you do).

If you follow this path correctly, Buddha believed, you would achieve a state of enlightenment and endless bliss called nirvana.

Interestingly, Buddhism may have emerged as a protest movement against Hindu orthodoxies, but Hindus, in their flexible way, simply claimed Buddha as their own, as one of the incarnations of Vishnu. Even though Asoka, India’s greatest ruler in ancient times, became a Buddhist, the religion always failed to take hold in India in quite the same way as Hinduism and it was in other countries that it gained converts – until the Dalits of the last half century. Buddhism reached its peak in the fifth century CE, but from there on it has dwindled, leaving behind only a superb range of monuments to testify to its status of old.