CHAPTER 7 METRO INDIA

‘It’s all changed. Suddenly India’s a candy store. It’s about wanting to own, to possess, to be in the newspapers, show off and be recognised.’

Simi Garewal, Rendezvous, Indian chat-show

IN MAY 2007, Indian newspapers were full of the news that one of the world’s tallest buildings is to be built in Mumbai. Is it the headquarters of one of the financial institutions that are now homing in on the city? Is it a centre highlighting the success of Mumbai’s IT boom? Or simply a communications tower? No, actually it is a private home – a 60-storey private luxury palace built for Reliance billionaire Mukesh Ambani, his wife and his three children. Ambani’s gleaming edifice will be draped with hanging gardens, and have its own theatre, health club and helipad, not to mention every kind of luxury silly money can buy. As property prices soar in Mumbai, Ambani’s apartment has been valued for resale at a billion dollars before a pile has even been driven.

Some say that Indian cities are at last learning to flaunt their new-found wealth, after long hiding it under a bushel – and Ambani’s tower is an apt demonstration of Mumbaikers’ (Mumbai people) success. Others describe it as symptomatic of the ‘new vulgarity’ that is sweeping India, as new wealth brings massive spending power to India’s lucky few. ‘It will not go down well with the public,’ said Mumbai newspaper columnist Praful Bidwai, ‘and there is a growing tide of anger about such absurd spending.’

India gets rich

The truth is that India’s boom is making (dollar) millionaires at an astonishing rate. More than ten thousand Indians are making it into the magic wealth bracket each year. And the super-rich are now very rich indeed, with five Indians alone worth nearly twenty-five billion dollars between them in 2003 – richer than the five richest people in Britain, which includes people such as Roman Abramovich. And beyond the megabucks, there are millions of other ordinary Indians doing very well out of India’s swelling economy.

The result is that a new arrival in India’s big cities cannot miss the outward signs of the consumer boom and a thirst for conspicuous consumption that can take even westerners by surprise. Malls are mushrooming in city after city. Shiny shops flash their top-of-the-range western products. Billboards proclaim the joys of luxury goods such as BMWs, Armani and Gucci. Television is punctuated by adverts for the latest products. Big cars and electronic goods are selling in huge numbers, drawing all the big western brands to India like flies. Everywhere, it seems, spending is king. And like all booming consumer societies, India is seeing soaring property prices as people compete for swanky apartments in town and grand villas in the hills.

What is surprising to those who see India as a rather spiritual, rather anti-materialist country – the natural heirs of the frugal Mahatma Gandhi – is that Indians are chasing wealth and consumer possessions with a zealous avidity. As Gurcharan Das, author of India Unbound, says, ‘Money, like sex, is out of the closet. Everybody wants to be rich, and live rich.’

Mumbai mania

Although some of the wealth has rippled out, it is the big cities that are the focus of this new money society – and nowhere more so than Mumbai. Mumbai was always the heart of Indian dynamism and growth, and the arrival of Bollywood made it the focus of Indian imagination, too. But in the last decade or so, it has become the epitome of the Indian boom. The city is buzzing. People flock here from not just all over India but all over the world. Its population has mushroomed from under 6 million in the 1970s to a staggering 21 million now, making it the world’s fifth largest city, if you include the whole conurbation. By the time you read this, maybe only Tokyo will be larger. By 2010, Mumbai will probably be home to well over 27 million people.

India’s leading industrial firms, such as Tata, Reliance and Birla, are all based here. So too are the nation’s main financial firms and institutions. The vast textile industries that first gave Mumbai its wealth and its power have long been in decline. Instead, the city now gets its energy and buzz from outsourcing and call centres, IT, entertainment and media – in other words, those very activities that propelled India from being a backward economy to a booming service stage economy, with no steps in between.

Mumbai murmurs

In a surreptitious way, Mumbai is in touch with the whole world in a way that few other world cities are. Every minute of the day, Mumbai’s call centres are answering thousands of calls that come in from ordinary households across America and Europe ringing to enquire about everything from their utility bills to how to order a cheque book. Every minute of the day, more and more routine tasks are being performed for the rest of the world by ‘outsourced’ Mumbai businesses. People in one Californian city find out what goes on at their local council meeting, for instance, from a website that is run from Mumbai, where reporters minute the meetings remotely by camera. Every minute of the day, another western company uses Mumbai’s IT workers to get them the best from their software.

There’s no doubt that Mumbai is a city on the move. Back in the 1960s, the port and textiles kept it going financially, while gangsters and Bollywood provided the image. In those edgy days, the city’s mafia dons ruled the roost, making their money from smuggling gold and electronic goods, as well as the more obvious narcotics and arms. And Bollywood film directors and actors cosied up to the mafia dons for funding since the law restricted funding from more legitimate sources. But all that began to change in the 1990s, as the freeing of trade restrictions robbed the mafia of their monopoly on electronics. Why run on the dark side, when you can make an even bigger killing legitimately by going into the IT business?

The new Mumbai

The Mumbai mafia is still there, of course, though diminished in influence, but these days it is more likely to be involved in land scams than smuggling, as Mumbai’s soaring property prices compete with its tight controls on the property market. The city is in the midst of a construction boom, and Mumbai’s skyline has changed radically as shopping malls, hotels and office complexes rise above the streets. So far the skyscraper has made little appearance here, but most people think Mukesh Ambani’s towering edifice will just be the first of many. The island of Mumbai is very small and crowded and building land is at a premium, so it makes sense to build upwards. In the mean time, however, land and property prices are rocketing as everyone tries to get in on the action

Bollywood is still there, too, bigger than ever, with massive audiences worldwide and stars capturing fees that would make even some Hollywood A-listers gasp. But the lifting of restrictions means funding now comes largely from mainstream sources. Interestingly, though, the IT and outsourcing boom that has underpinned Mumbai’s recent growth may not be its engine for the future. Many in Mumbai see the city’s future in London – that is they see Mumbai as a powerhouse of global finance and ‘knowledge processing’.

Mumbai is well down the world financial list at the moment, but an Indian government report issued in June 2007 highlighted just how much Indian firms such as Tata pay for international financial services. It’s 13 billion US dollars now, but within the next eight years could be up to 70 billion – and nearly all that money is going abroad, to London, New York, Singapore and Hong Kong. The report argued that with that kind of money involved it really made sense to develop Mumbai as an international finance centre. Mumbai has already got its computerised trading floor, the Bombay Stock Exchange. Who knows if it might not have its own big bang soon, providing some of India’s arcane financial laws are clarified?

BOLLYWOOD

Few things have brought the modern India into western view quite as vibrantly as Bollywood films. The name was invented as a joke – a conflation of Bombay where the films are made and Hollywood, and it has stuck – even in India where Bombay is now called Mumbai. Film is much, much bigger in India than it is anywhere else in the world. Many, many Indians don’t have access to television, but most are in walking distance of a cinema, and prices are comparatively cheap. That makes for an audience of up to a billion – numbers that Hollywood can’t even dream of.

To cater for this vast audience, Bollywood has developed a remarkable production line for churning out film after film – near enough a thousand every year, which makes Hollywood look sedentary. Visiting a Bollywood film set, you might think everything is chaos, as people run to and fro arguing and shouting, and nothing seems to be ready. In fact, this chaos disguises a remarkably efficient business that churns out films on schedules and budgets the average Hollywood director would blanch at.

One reason Bollywood is able to do this is because films have become formularised. Filmmakers know what audiences want and they deliver. Of course, films of all kinds are made by all kinds of directors in India, just as they are all over the world, but the classic Bollywood film is designed to appeal to audiences all over India. They are made in Hindi, so there are no language barriers, and they carefully tread a line between appealing to religious ideals and avoiding offending any of the audience.

The classic Bollywood film thrives on what is sometimes called the masala format – which basically means throwing in a little of something for everyone – romance, comedy, violence, drama, music and dance. Almost every film has its song and dance sequences, and these have become Bollywood’s most distinctive feature. The dance breaks are often nothing to do with the plot, and the reasons for going into them are frequently tenuous in the extreme. But they are almost invariably dynamic and sexy, and shot in exotic locations. In the older films, they were shot in lush forests and by waterfalls, and the dance moves were strongly traditional Indian. Now they tend to be far more urban. Often a Mumbai street will be closed down while a Bollywood dance sequence is shot. Recently sequences have been shot in glamorous foreign locations where Indians on the up might go, such as Manhattan or even London’s Docklands. The dancing and music has become far more modern and risqué, with hip-hop, R’n’B and other western dance music blended into the more familiar Indian styles. Most Bollywood actors are dancers, as they have to be to cope with these scenes. Even Amitabh Bachchan, Bollywood’s most famous star, has to perform his own dance sequences well into his 60s. But very few of them are singers, and the songs are invariably done by a professional ‘filmi’ singer singing in sync with the actor’s lip movements, which can sometimes look weird to western eyes unused to it.

It is not just the inclusion of dance numbers that is formularised. So too, often, are plots. There aren’t many Bollywood films that don’t feature a young, dispossessed man fighting against all the odds and winning, thwarted in the path of true love by many obstacles – but ultimately getting the girl, and the approval of both his and her parents. Family bonding and betrayal are common themes, and almost every film has its dream sequence and its wild festival sequence, complete with comic characters.

Sex scenes, of course, simply do not occur. Even kissing on screen is strictly taboo. That doesn’t mean the films are not erotic. The heroine invariably dances in a highly suggestive manner at some moment in the film and there is frequently a wet sari scene. But physical contact between the lovers is strictly off limits.

All the same, as the world outside becomes more and more aware of Bollywood, and audiences grow in both in both the UK and USA, with more ‘sophisticated’ tastes, so Bollywood films are trying to cater for more of a ‘crossover’ market. Films are becoming a little racier and modern. Settings are becoming more cosmopolitan. And plots frequently feature a returning emigrant or NRI (Non-Resident Indian) who is clearly really in touch with the contemporary world. Budgets too are getting bigger, and production values have been going up to meet the demands of the new audience. Yet there are those who say that as Bollywood gains new audiences abroad, it is losing some of its less sophisticated fan base at home.

It is hard to overestimate just what a big role Bollywood plays in people’s lives in India. Bollywood stars such as Aamir Khan and Preity Zinta have the kind of following that is beyond even some of the biggest Hollywood stars. Indians are fascinated in their lives, and gossip. Recently the hottest-selling book in India has been Shobhaa De’s Bollywood Nights. De is often referred to as Bollywood’s Jackie Collins, and her book features the sultry actress Aasha Rani and her exploits in the film business. The picture it paints of Bollywood is far racier than one might expect from the saccharine films, with its themes of power, greed and lust. But De insists that this is what Bollywood is like. ‘It is the underbelly that defines what Bollywood actually is but rarely wants to acknowledge about itself.’ It makes sense, since in the early days, filmmakers had to get their funding from the Mumbai mafia, because more conventional sources of finances were closed to them. Although most films now are funded from legitimate sources, Bollywood is probably far from pure. Either way, De’s readers seem to be loving it.

MUMBAI’S DABBAWALLAHS

Every morning without fail, a remarkable barefoot army of five thousand goes into action in Mumbai. These are the dabbawallahs. Dabba is the Hindi word for ‘box’ and the dabbawallah’s task is to deliver a home-cooked lunch in a drum-shaped aluminium lunchbox to Mumbai workers. The lunch really is home cooked, cooked by each worker’s wife in a time-honoured tradition dating back to the time of the Raj, when many Mumbai kars (locals) couldn’t stand the food served up by British companies. It sounds quaint, but it is an extraordinarily efficient business. Every day the dabbawallahs pick up their round of boxes from the homes at precisely the same time and head off into town on the train or bicycle with the boxes balanced on their heads. Two hundred thousand meals get delivered on time to the right person each day every day, come drought or monsoon.

Mumbai’s underbelly

Cheek by jowl with Mumbai’s IT glitz and Bollywood glamour, its shopping malls and finance halls, you will find the darker side of the city. Mumbai has always been a city of extreme contrasts, with a massive gap between the haves and the have-nots. In the days of the Raj, the British would swan about in their faux-Anglaise, tree-lined streets with their great Victorian piles while the Indian urchins would only venture in occasionally from shanty town Mumbai. Now the British quarters are a backwater, and rich and poor Indians live side by side in the heart of the city. The proximity is extreme and the contrasts are dramatic. Luxury apartments rise quite literally from amid the most squalid shanty towns imaginable. Mumbai moguls must step over workers whose only bed is the pavement as they descend from their BMWs. Poor little boys and girls work in some of the world’s worst sweatshops for eighteen hours a day, in dangerous conditions for peanuts, while just a street away the city’s IT whizz kids tap away in gleaming air-conditioned offices earning them the kind of money that makes them ‘crorepatis’ (Mumbai’s super-rich with a fortune of over Rs 1 crore, or 10 million rupees) by the time they are 30.

Accommodation is at such a premium that Mumbai’s masses of poor migrants simply cannot find anywhere to live, let alone anywhere affordable. This is a city in which not just thousands, but hundreds of thousands sleep rough every night, on pavements, in doorways, behind crates, in ditches, in drainage pipes – and there countless feral children. Those who find a home in Mumbai’s vast shanty towns, with their open sewers and rat-infested lanes, consider themselves lucky. Up to a million are believed to live in the squalid slum of Dharavi in an area half the size of New York’s Central Park and over Mumbai as a whole, some ten million people live in slums that can only be described as atrocious.

AMBY VALLEY

Out in the Sahyadri hills east of Mumbai is one of the most extraordinary projects that India’s boom culture has yet produced. Here under construction is Amby Valley. Amby Valley is the ultimate gated development for the super-rich – not just an apartment block or a street, but a complete city carved out of the rocks and scrub of the Deccan hills. The man behind Amby Valley is Subrata Roy, whose Sahara Parivar group has put him in the realm of India’s mega-rich. He describes it as a ‘dream city’. It is certainly surreal. The complex is completely surrounded by a high fence and patrolled constantly by armed guards and dogs, like some strange prison camp in which the prisoners are on the outside. Inside the fence, apart from the multi-million dollar homes, are four artificial lakes, an international-standard golf course, an airstrip, a lagoon with an artificial beach and umpteen upmarket restaurants. To come are an English-style public school, a 1,500-bed state-of-the-art hospital, shopping centres and an ‘economic zone’, which would allow Amby Valley residents to avoid any contact with the outside world whatsoever. The perfectly manicured lawns, the litter-free streets and the smooth roads are more akin to Stepford than India. The only problem so far is that there are not many inhabitants. An advertising campaign, which featured sporting stars such as Anna Kournikova, has so far attracted India’s mega-rich to buy just a few hundred of the 7,000 plots on offer by 2012. So it is possible that Sahara Lake City, as it is also called, will be genuinely deserted.

Selling the slums

The people who live in Munbai’s slums have been gradually hauling themselves up by their bootstraps. They may be desperately poor, and crime, disease and deprivation may infest their crowded shanties like the mosquitoes that once swarmed in the malarial swamps on which they were built, but many shanty dwellers work hard, and have made improvements. Many of the people who live in the shanties are the skilled leather and textile workers on whom the city’s industry depends. Some slums now actually have an electricity supply of sorts. Some even have running water, albeit for one hour a day. A survey of Dharavi in 2002 revealed that 85 per cent of households have a TV, 75 per cent have a pressure cooker, 56 per cent a gas stove and 21 per cent a telephone. This sounds better than it is of course – because a household may contain dozens of people, and many people in Dharavi don’t even live in households. But the improvements are there.

Ironically, though, these very improvements are beginning to create a problem for areas like Dharavi. As life in them gets a little better, so they become more attractive to those with money. Astonishingly, even Dharavi has got sucked into Mumbai’s property boom. A 21-square-metre apartment that could be brought in Dharavi for US$1,500 at the turn of the twenty-first century now goes for US$11,000 – way beyond the purse of any new migrant who is forced further out to the squalid slums now growing at the city’s edge.

The poor may be squeezed out even further as the inner-city slums improve. Dharavi is right in the heart of the city and is being eyed up as prime real estate by developers. In May 2007, the state authorities announced a plan to bulldoze Dharavi away entirely in a US$2.3 billion improvement project by a private developer. The developer will get land for housing and commercial development and in return must provide free new housing for Dharavi’s displaced poor. Mumbai’s biggest slum swept away and its people given wonderful new homes for free? It sounds too good to be true – and it probably is. As some outraged activists have pointed that the whole plan is based on the government’s official estimate that there are just 57,000 families living in Dharavi. But of course, because of its nature, most of Dharavi’s inhabitants are not recorded officially. Five to ten times as many people probably live here and all will be made homeless if the bulldozers move in.

PROFILE: MUKESH AMBANI

‘I think that our fundamental belief is that, for us, growth is a way of life and we have to grow at all times.’

As big businessmen go in India, Mukesh Ambani is pretty much the biggest. He talks big and thinks big, and if some of his plans come to fruition then he’ll prove to have acted big, too.

Born in 1957, Ambani is one of the two sons of the patriarch of India’s biggest company Reliance. He got a chemical engineering degree in Mumbai then went to do an MBA at Stanford Business School in the USA – until his father called him back to knock Reliance’s textile and petrochemical business into shape. At once, he began to think big (too big, some said at the time). But Ambani got huge and successful plants under way – not the least of which was the giant oil refinery at Jamnagar, which turned India into a net energy exporter for the first time when it came online in 2000. When his father Dhiurubhai died in 2002, a bitter dispute with his younger brother Anil became a tabloid sensation. Nonetheless, he achieved the first of his big dreams for India in 2003 when his Infocomm telecom company cut the price of a phone call down to a penny a minute in India.

Now Ambani is on a roll and his schemes are nothing if not ambitious. For starters, he’s masterminding an US$11 billion project to build in just four years two satellite cities outside Mumbai and Delhi, each with a population of five million. But this is one of his smaller projects. His grand scheme is to do nothing less than revolutionise the whole of India’s retail and farming sector. On the farm side, he plans to create 1,600 farm-supply hubs across the country to provide farmers with technical know-how, low-cost credit, seeds, fertiliser and fuel – and also to buy their produce. He is in the process of training tens of thousands of workers to build good prefab warehouses, good roads and set up good transportation systems to ensure the food gets to the next part of his scheme – the supermarkets.

In a country where 96 per cent of shops are small family affairs, Ambani plans to become the ‘Wal-Mart in India’ as he calls it – incorporating the latest logistics technology. Only rather than bulldoze the smaller shops out of the way he is hoping to incorporate them into the chain. A trial partnership with the small Sahakari Bhandar chain in Mumbai has proved a huge success, and Ambani now plans to build big superstores on the margins of small cities before moving on to the megacities. So confident is he that this combined assault on farming and retail will work, he not only predicts it will bring India an extra US$20 billion in agricultural exports annually but that he can beat Wal-Mart at their own game in India. Time will see if he is right.

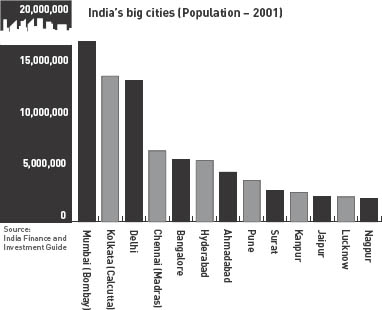

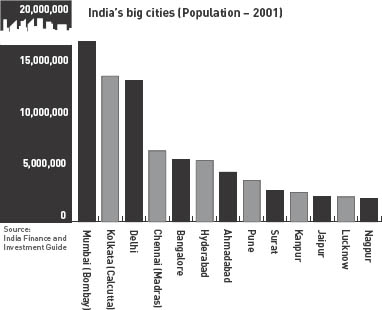

Delhi bread

Although it is Mumbai that has attracted the world’s attention, India’s three other big cities – Delhi, Kolkata and Chennai – have been expanding tremendously, too. Delhi and its surrounding area has a population that is touching 21 million, putting it only just behind Mumbai as the world’s sixth biggest megacity. Kolkata, too, is in the top eighteen, and Chennai is not that far behind.

Delhi’s population is growing by 5 per cent a year as migrants flock here from all over the Ganga plain. There are not the same space restrictions as there are in Mumbai, and the city is sprawling far and fast out over the plain, like a great dusty coloured rash. In just a few years, the expressway has become the focus of a whole string of mushrooming dormitory towns. In the last few years, Delhi has become even more of a magnet for foreign investment than Mumbai. One reason is that it is physically closer to the heart of one of the world’s biggest and fastest growing consumer markets. It is no coincidence that consumer-goods manufacturers are at the forefront of new businesses, outdone only by the retail sector, which is growing explosively here. Both Wal-Mart and Tesco are starting their Indian operations in Delhi. A second reason for Delhi’s growing attraction is that there is more space here than in Mumbai. A third, and perhaps crucial, reason is that Delhi is getting its act together with infrastructure. Delhi city is lucky to have a good government – in stark contrast to Mumbai and many other Indian cities.

Staggering forward

Delhi’s mayor since 1998, Sheila Dikshit has acknowledged that the two big problems that stand in the way of progress in any big Indian city are poor infrastructure and official corruption – which of course go hand in glove. And she seems to be doing more than most to tackle them. In his book In Spite of the Gods, Edward Luce describes beautifully the dilemma faced by any politician trying to improve infrastructure. When she tried to change Delhi’s water-supply system, which employs a vast and unnecessary labour force yet singally fails to deliver water to most of the city’s population, she found herself in a real quagmire. When she put up the price a little to try and extend the supply, she was accused of trying to fleece the poor – even though all Delhi’s public water goes to the middle class, and the slums get none. But she has persevered, and scored some notable successes.

The most spectacular of these, of course, is Delhi’s brand new Metro. By the time it is completed, it will be one of the world’s biggest underground networks, with 225 stations and lines stretching out into every corner of the city. No longer will Delhiites have to spend hours struggling through the city’s traffic. Even the poor will be able to hop on the Metro and cross the city in a brief journey. Work started on the Metro in 2004 and by mid-2007 almost one hundred stations were built. Funding for the project comes from a partnership of private Japanese and German money with Delhi government money, and Dikshit has done her best to ensure government are as little involved as possible, allowing the project to stay remarkably free of the corrupt inefficiency that dogs so many Indian public projects.

That said, Delhi remains a vast, dirty city, packed with vast and atrocious slums as well as new shopping malls, and the improvements, though important, are still small. All the same, a quality of life report by the consulting firm Mercer in 2007 ranked Delhi as India’s best city in terms of standard of living, though admittedly the competition wasn’t that stiff.

Hot Delhi

Delhi has always been seen as the strait-laced sister of racy, dynamic, splashy Mumbai, always just a little behind the times. Awash with history, yes, with its domes and minarets and elegant Mughal relics; brimming with traditional colour, too, with its cacophony of street sellers and profusion of local food. But the country’s capital has always seemed, well, just a little past it compared with the vibrancy of Mumbai. Yet there is a sense that Delhi is now beginning to shed some of its conservative image. Young people with money are beginning to make an impact. Bars and restaurants with London and New York inspired interiors are opening. Smart clubs pump away RnB late into the night. And all over the city bright young things are yabbering away on their mobiles or sipping cappuccinos in Baristas (India’s answer to Starbucks). But of course, the cows are still there in the streets as they always have been; and old men smoke beedis as they always have done. Maybe it’s a sign of the times, though, that street children meet tourists at the station to offer them a quick package tour of their haunts. Now even destitution can be turned into a money-making venture.

Beyond the big four

Although the focus of attention has very much been on India’s big four cities of Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata and Chennai, plus the IT tigers Bangalore and Hyderabad, India’s smaller cities have been swelling, too. Between the 1991 and 2001 censuses, the number of Indian cities that were home to more than a million people shot up by almost half to 35. Medium-sized cities such as Pune, Nashik and Kanpur are all growing rapidly. The real powerhouse, though, is Surat.

Tucked high up the west coast in Gujarat, Surat was once the main port on this side of India, until it was completely eclipsed by Mumbai. Now, though, it is undergoing something of a renaissance. The Rough Guide to India dismisses Surat as ‘of real interest only to colonial history buffs’. But if not offering much to tourists, it offers a great deal to migrants who are flocking here in their thousands. Surat is not a high-tech boom town, but a genuine industrial focus, and offers jobs to ordinary Indians in a way that neither Bangalore nor Hyderabad can. Indeed, Surat was ranked the No. 1 city in India in which to earn, invest and live. As a result, it is growing faster than any other Indian city, swelling from 2.8 million inhabitants in 2001 to 4.9 million in 2006. Indeed, according to the City Mayors network, Surat will be the fourth fastest growing urban area in the whole world between 2006 and 2020, by which time it will be up among the ranks of the megacities.

LIFTING THE SECOND TIER

Aware of the huge pressure on the big four cities, the Indian government has launched a deliberate plan to upgrade 62 second-tier cities and get them to provide alternative growth centres. Some US$29 billion is to be spent between 2007 and 2014 on upgrading the infrastructure and environment of these second graders in the hope that this will be enough to get their economies moving. In a phone interview with the New York Times, Montek Singh Ahluwalia, the Indian government’s chief economic planner said, ‘One hundred million people are moving to the cities in the next ten years, and it’s important that these hundred million are absorbed into second-tier cities instead of showing up in Delhi or Mumbai.’ First on the list is Nagpur. Already the government has set aside US$280 million for the city to be spent upgrading roads, creating parks and expanding and updating the airport to international status. An eco-friendly mass transit system is on its way and so too are economic zones to attract business with good water, electricity and fibre-optic cables. It is an ambitious scheme, but there is a good chance that the second-tier cities might provide the key to India’s future economic growth.

Heavy industries like Reliance petrochemicals and Essar steel are based in Surat, but the big job-spinners are textiles and diamonds. Surat is the synthetic fibre centre of India, turning out 40 per cent of all India’s humanmade fibres on over six hundred thousand power looms spread across the city. And if it is India’s synthetics capital, Surat is capital of the entire world when it comes to diamonds. Surat’s diamond business is huge. Anything between 70 and 90 per cent of all the world’s diamonds are cut and polished here. There are over half a million people working in the diamond industry alone in Surat, and their jobs, by Indian standards, are quite well paid. The only problem for men who come to work here, find a good job and end up staying is the desperate shortage of women. Surat is a man’s world, and looks like staying that way for a while.