A real chef needs only one knife. It is his sword. It is his best friend. It is everything to him.”

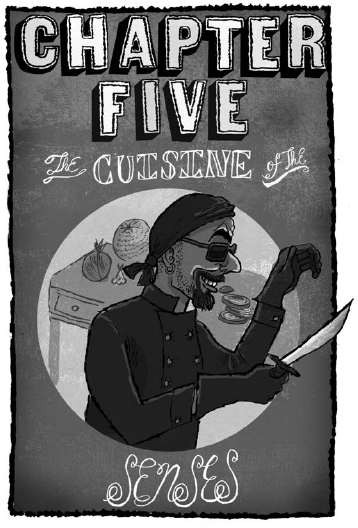

A man of the type often called dark and swarthy stood behind a stove holding a large knife in his gloved hand.

He wore a black chef’s coat and, covering his bald scalp, a black scarf decorated with skulls and crossbones. Adding to the pirate look: a hoop of gold in his left ear and a goatee ringing his mouth.

He also wore a pair of extremely dark sunglasses.

The glasses of a blind man.

He raised the knife higher so it gleamed in the light. “A real chef would as soon give up his knife as cut off his arm.”

Then he sliced his knife through the air if he were about to cut off his arm in demonstration.

It was, in fact, a demonstration kitchen—a class-room clad in stainless steel—and facing him, on the other side of the stove, sat an audience of twelve.

His students gasped. Then let out a collective sigh of relief when the knife landed point-down in a cutting board.

“Other knives, like these here—bread knife, paring knife, boning knife—” He pulled the knives off a magnetic rack one by one, as easily as if he could see them. “They’re for amateurs.”

He smiled slyly, the stove’s blue-flamed burners reflecting in his sunglasses. “Or for carnival tricks.”

Without warning, he tossed the three knives into the air and juggled for a good thirty seconds. The knives spun so fast they were a blur.

Until he let them drop in quick succession, chopping an array of vegetables so they splayed on the counter in perfect rainbow formation.

An astonishing show, even if he hadn’t been blind.

“Always keep your knives sharp. Contrary to popular belief, they’re much more dangerous when they’re dull.”

The class burst into applause. Slightly muted applause because, like the chef, they all wore rubber surgical gloves. (He insisted that everyone keep their hands covered in the kitchen.)

But there was one person whose applause was mute for the simple reason that she was not clapping.

Yes, it was Cass. The pointy-eared and very grim-faced girl in the front row.

Her mother had received the brochure for the cooking class not long after Cass first confronted her about the adoption. It boasted a picture of the chef in his sunglasses, posing like a movie star.

“Look, Cass—what a great way for us to spend some time together!”

“Why would we want to do that? We already live together,” Cass had pointed out.

“Cass…!”

“Well, why a cooking class?”

“How about so we can start having some home-cooked meals?”

“What’s the matter with Thai takeout? That’s what we used to always have.”

“Exactly! I want to fill the house with the smells of cooking. The smells of childhood. The smells you will remember your entire life,” her mother had answered.

But as far as Cass was concerned, her entire childhood had turned out to be a lie. She didn’t care how it smelled.

And now here she was having to sit in class with her mother when she should have been hunting for the Tuning Fork with Max-Ernest and Yo-Yoji.

“I can’t believe you like him. He’s such a showoff,” Cass whispered a few minutes later, when they were taking turns chopping zucchini.

“How could he be a showoff?—he’s blind. Anyway, he has a right to be. Señor Hugo is one of the greatest chefs in the world. He invented the Cuisine of the Senses,” said her mother reverently. “And so handsome, too,” she added.

As if on cue, Señor Hugo stepped up behind them. “Oh, I wouldn’t say invented. Maybe developed…”

He spoke with the lisping Spanish accent known as Catalan—the accent of his native city, Barcelona, or as the Catalans pronounce it, Barthelona.

“I’m sorry—may I…? I can tell by the noise you make that you’re not using the proper motion.” The blind chef put his hand over Cass’s mother’s, gently correcting her chopping technique.

She blushed. Cass rolled her eyes. Her mother’s crush was so obvious!

“All the senses are important to a chef—but luckily for me, sight is the least important,” continued Señor Hugo.

Finally, he let go of Cass’s mother’s hand. (A little too late, in Cass’s opinion.)

“I always wait to taste the food I cook,” he said to the room at large. “Take a curry. First I dip my finger in and feel the texture. Is it too powdery? too foamy? I listen to the sounds. That hiss means it’s not hot enough. That sizzle? Too hot. And at every stage I smell smell smell. Did you know that what we think of as taste is mostly scent? By itself the tongue only detects five flavors: sweet, sour, salt, bitter, and one other—have any of you heard of umami?”

“Yeah, it’s the taste of fat,” said Cass knowingly.

Señor Hugo nodded. “Yes, some people say that, although I prefer to call it savoriness or deliciousness.”

He turned to the room. “Only when a dish is finished do I dare taste it. And when I do, I feel as if at last I can see, as if I have gained a kind of second sight.… Even so, there are some things I can taste only in my head.”

“You mean, there are things you can’t cook?” asked Cass’s mother in surprise. “A master chef like you.”

“All artists strive to greater heights, do they not?” the chef responded. “Take chocolate, which is my passion…”

“Oh, it’s my passion, too!” said Cass’s mother.

Cass groaned inwardly.

“My life’s ambition is to make the ultimate bar of chocolate. The best, the purest, the darkest chocolate of all time. As close to one hundred percent cacao as possible.”

It figures he would make chocolate, thought Cass, imagining the pirate chef commanding a ship full of child slaves.

“I keep trying to find the right equipment—”

He gestured toward the wall behind the audience. Sitting on a long steel shelf were dozens of cooking devices: narrow siphons, bulbous whisks, tall Bunsen burners, double, triple, and even quadruple boilers. They looked like they belonged in a chemistry lab rather than in a kitchen.

“I can taste it in my mind. But I have not yet made my chocolate a reality.”

“Too bad you don’t have the Tuning Fork,” said Cass as snottily as she could.

Señor Hugo whipped his head around. “The what…?”

“The Tuning Fork. The mythical cooking instrument made by the Aztecs. Anybody who had it could make any taste he wanted. Since you’re such a great chef I just thought you would know what it was.”

“Go on. I’m very interested in culinary history,” said the chef, his attention fixed on Cass. She could almost have sworn he was staring at her.

“That’s it. That’s all I know about it…” She faltered, suddenly realizing the implications of what she’d just said.

Of what she’d just done.

“So how did you hear about this… Tuning Fork?” Señor Hugo persisted.

“I don’t know. Maybe at school…?” Her voice squeaked unconvincingly.

“You must go to a very interesting school,” said Señor Hugo.

According to Mr. Wallace, the Tuning Fork might not even exist. But that wasn’t the point.

Never talk about the Terces Society. Or anything to do with the Terces Society. It was the Society’s first rule. Almost its only rule.

“Since you’re such an expert in cuisine you must come to my restaurant as my guest!”

“Did you hear that, Cass? What an honor!” gushed her mother.

Their classmates nodded and clapped in envy.

“Señor Hugo’s restaurant is famous,” said one of the aspiring chefs. “Everybody eats in the dark—so you have to guess what your food is.”

“People wait months for a reservation,” said another. “It’s like getting the golden ticket!”

“But we can’t,” said Cass. “Remember, I’m supposed to work on that report with Max-Ernest and Yo-Yoji? The one about chocolate and child slavery? It’s due the first day of school.”

(The three kids had all told their parents the same thing; their first “homework” session was scheduled for Saturday.)

“Well, then, your friends should come, too. On Saturday, we will be featuring a multi-course chocolate tasting menu. It will be research. For your report… oh, and don’t forget your Tuning Fork!” joked Señor Hugo.

“Ha ha,” said Cass, not laughing.

She tried to cheer herself up. As much as she disliked Señor Hugo, what real harm could it do that he knew about the Tuning Fork?

After all, she reasoned, he was a chef, not an alchemist. There was no way he could know Dr. L or Ms. Mauvais. It wasn’t as if he were a member of the Midnight Sun.

But it was no use; she felt terrible.

At least the blind chef wouldn’t see the tears of guilt welling in her eyes.