The match flickered out.

But not before the commotion had drawn the attention of their waiter. They could hear him running toward their table.

“Can I help you with something?”

“Yeah, where’s my mother?” Cass demanded. “And what about everybody else—?”

The waiter said he had no more idea where Cass’s mother was than they did. He was certain she wasn’t in the bathroom; he had just finished cleaning it. As for the other customers being gone, that was no mystery; they’d finished dinner and gone home, naturally.

“I’m sure your mother is fine—she probably needed some air. Although if a customer can’t be bothered to ask for help, we really can’t be held responsible… Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’ll just go get the check…”

He scurried out without waiting for a response.

“The check? How are we going to pay if your mom doesn’t come back?” asked Max-Ernest, distressed. “Do you think they’ll make us wash dishes?”

“Forget the check—we have to find her!” Cass stood up, reaching into her backpack. “Come on—”

Quickly, she struck another match, and with this one lit a candle.

From what they could see, the restaurant looked much like any other. With the distinction that there were no windows. Nor were there any pictures on the walls. Nor any color or decoration whatsoever. It could almost have been the dining hall in a prison.

“How did they clean up so fast?”

Yo-Yoji gestured toward the tables spread out around the room. They were immaculate. Place settings gleamed. Folded napkins stood at attention. It looked as though the restaurant were just about to open. You’d never guess that minutes ago it had been full of diners.

In contrast, their own table was covered with food and spilled drinks.

Cass’s face turned angry in the candlelight. “I know where my mom is—the kitchen!”

She pointed to the double doors at the far end of the room.

“I’ll bet she went to talk to Hugo. She’s so in love, she couldn’t wait to tell him how good dinner was…”

The double doors turned out to be double-double; that is, behind them was another pair of double doors.

As soon as Cass pushed through this second pair of doors, they were blinded by light. Compared to the darkness of the dining room, the kitchen seemed as bright as a hospital.

As their eyes adjusted our three friends turned pale:

A man in a chef’s coat held a cleaver high in the air.

As they watched, he brought it down and chopped—

a carrot.

The three kids exhaled in relief.

“Who’s there?” he asked spinning around, knife in hand.

It wasn’t Hugo; it was his sous-chef. * But evidently, he too was blind.

“We’re customers,” said Cass. “Have you seen my mom? I mean—did anybody else come in here?”

The sous-chef shook his head sternly. “No. And this room is strictly off limits,” he growled.

“What about Hugo? Where is he?” Cass persisted.

“Gone for the night. As you should be.” He chopped another carrot for emphasis.

Yo-Yoji silently motioned to his friends: Let’s get out of here.

“Why do you think the kitchen is so lit up if all the chefs are blind?” whispered Max-Ernest as they headed back into the dining room.

“Beats me—the whole place is creepy,” said Yo-Yoji.

Cass didn’t say anything—just hurried forward holding the candle in front of her.

They found the entry room deserted. Even the scent bouquets were gone.

“Do you think she left with him?” asked Yo-Yoji. “Would your mom do that?”

“I dunno,” said Cass, growing increasingly distressed. “It’s so weird.”

The waiter came out of the hallway looking harried.

“Cassandra? Is that you?”

“Yeah, we’re right here. Did you find my mom?”

“I just spoke to Señor Hugo. He said not to worry about the bill—it’s on the house. And he left you this—”

The waiter held out an envelope, which Cass anxiously accepted.

“Good-bye, we have to close up now,” he said, ushering them toward the front door. “I hope you enjoyed your dinner.”

The blind waiter bowed and walked quickly back in the direction of the main dining room.

As soon as they got outside, Cass tore open the envelope. There was a handwritten note inside.

“What does it say?” asked Max-Ernest.

“Is it from your mom?” asked Yo-Yoji.

“Not really,” said Cass after a moment, shoving the note in her pocket. “I mean, yeah, it’s from her, but she says the dark was making her too nervous and she went home.”

“Really? Without saying good-bye?” asked Max-Ernest, surprised. “How are we supposed to get back?”

“Uh, bus. She said to take the bus.…”

Max-Ernest looked at his friend. “Why are you acting so weird?”

“I just… realized I don’t have any bus money,” Cass stammered.

“Well, I do. So we’re cool,” said Yo-Yoji. “But you sure everything’s OK?”

“Totally,” said Cass, forcing a smile. “Why wouldn’t it be?”

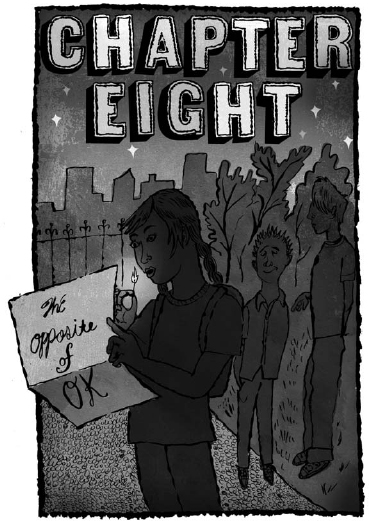

But it wasn’t OK. It was the opposite of OK.

Although Cass didn’t share the note in her pocket with her friends, I will share it with you here. I believe it’s too late now for it to make any difference. The penmanship, I think you’ll agree, is remarkably neat for somebody who couldn’t see:

Cassandra—

If you value your mother’s life, bring me the Tuning Fork in two days’ time. Tell no one—not even those two boys with you. If I learn that you have shared this note with anyone, the deal is off and you will never see your mother again.

H.