Introduction: Through Bright Glass

When you half lose yourself in a work of art, what happens to the half left behind? The critical vocabulary to describe that sensation is lacking, but it is a familiar feeling, nonetheless. When most carried away, audiences of even the most compelling artwork remain somewhat aware of their actual situation. Ideas about this kind of semi-detachment play a crucial and generally unrecognized role in shaping a wide range of nineteenth- and twentieth-century fiction. In such works, the crux of an aesthetic experience is imagined, or depicted, or understood as residing neither in complete absorption in an artwork nor in critical detachment from it, but in the odd fact of both states existing simultaneously.

In George Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss, for instance, the first chapter moves suddenly from an account of the young Maggie Tulliver at play to a description of the “really benumbed” arms of the narrator who has been watching her:

It is time the little playfellow went in, I think; and there is a very bright fire to tempt her: the red light shines out under the deepening gray of the sky. It is time, too, for me to leave off resting my arms on the cold stone of this bridge. . . .

Ah, my arms are really benumbed. I have been pressing my elbows on the arms of my chair, and dreaming that I was standing on the bridge in front of Dorlcote Mill, as it looked one February afternoon many years ago. 1

Eliot’s doubled elbow-rest (bridge and chair-arm both) offers a way to think about the reading of the novel itself: not only am I here reading, I am also there watching. The narrator turns into a simulacrum of the reader, whose dream-like entry into Maggie’s world is bodied forth in the narrator’s ellipsis-marked discovery that his or her arms have been pressing onto bridge and armchair simultaneously. That dual experience of being both at home in one’s own study and at the same time immersed in an invented world is intimately linked to Eliot’s sense that novels themselves may become testing grounds for universal laws of ethics and of sociability. Novels help Eliot to explore how little you grasp of the other minds at work around you and to chart some of the ways in which their own wavering, flickering attention misunderstands you in just the same degree that you misunderstand them.

Take another example, a moment at the end of Henry James’s The Ambassadors. A minor character, Marie Gostrey, proposes to our hero Lambert Strether—only he is too busy thinking about the proposal’s impossibility, and how he will refuse her, to notice that she continues to talk to him. James brings his cognitive glitch to the reader’s attention with a wry aside about Strether’s serene thoughts on how well his refusal will be received: “That indeed might be, but meanwhile she was going on.” That sense of the ongoing—we might call it the novel’s version of “parallel processing”—puts into view the discrepancy between one’s actual position and one’s conceptual location. The Jamesian novel becomes a seismograph of the divergence between experience and event, showing where the mind goes when it wanders.

James’s little joke about Marie “going on” while Strether mentally sketches out her future responses is a register of the novel’s capacity to register twists and turns of experience that James himself calls “disguised and repaired losses” and “insidious recoveries.”2 A novel (or a painting or a film) that generates in its audience the sensation of semi-detachment is in some ways replicating and holding up for examination an experience familiar to the real world. Late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century readers are so interested in the ways that a novel’s free indirect discourse half-enters into a character’s mind because of their interest in how well or how poorly they are able to predict and understand the actions and the thoughts of other human beings in everyday social settings—human beings who are, each and every one, partially absorbed in their social situation and partially detached from it.

One April morning, biking over the Mass Pike listening to my iPod—traffic noise in one ear, the Carter family in the other—I suddenly saw that moment in James as a fact of life, not art. Holding two things in my head at once—“Cabin in the Pines” and the pile of broken glass I’d have to dodge at the end of the footbridge—suddenly struck me less as a quirk of the Jamesian narrator and more as a record of something that had been happening to me all my life, but only happening in the most evanescent unsatisfactory way: happening, then immediately vanishing again because I lacked the vocabulary to make sense of it, to give it a name and attributes. The title of Sherry Turkle’s jeremiad about overly virtual lives—Alone Together—began to strike me less as an indictment of our present social condition than a description of our perennial residence in a state of mental quasi-abstraction. I biked straight off that bridge and into the library. Sometimes it seems I haven’t left since.

MINDS SOMEWHERE QUITE ANOTHER

It is, I mean, perfectly possible for a sensitized person, be he poet or prose writer, to have the sense, when he is in one room, that he is in another, or when he is speaking to one person he may be so haunted by the memory or desire for another person that he may be absent-minded or distraught. . . . Indeed, I suppose that Impressionism exists to render those queer effects of real life that are like so many views seen through bright glass—through glass so bright that whilst you perceive through it a landscape or backyard, you are aware that, on its surface, it reflects a face of a person behind you. For the whole of life is really like that: we are almost always in one place with our minds somewhere quite another.

Ford Madox Ford, “On Impressionism”

In recent years, the concept of virtuality has emerged as one important way to think about the interplay between actuality and aesthetic mimesis.3 Semi-Detached’s distinctive approach to the concepts of the actual and the virtual results in part from its attention to what we might call artisanal questions—on what it means for writers (and other artists) to take note of and reflect on the partial nature of such experiences of aesthetic dislocation as practical problems related to getting their work done. Semi-detachment, as a concept, helps shed light on how writers understood what it meant for readers to experience the world of a book as if it were real, while nonetheless remaining aware of the distance between such invention and one’s tangible physical surroundings.

I came to Ford’s essay very late in the writing of this book: How many hours, or even minutes, did it take him to jot down the telling image (“real life . . . seen through bright glass”) I’d spent almost a decade not coming up with? So many of the examples I’d been setting aside for further thought—Buster Keaton’s double take when he realizes that his beloved has overheard his practice proposal of marriage; my own discovery that my computer was burning my thighs while my on-screen avatar roamed some virtual world—were imperfect approximations of that doubled “impression” Ford so elegantly sketches. Ford presumably proposes a half-reflective, half-transmissive piece of glass as an apt metaphor for impressionism because that bright glass creates an unsettling double exposure, leaving the gazer uncertain which view has priority.

Ford’s image offered me a new way to think about those elbows in Eliot, the ones that rested simultaneously on a cold, stone bridge and a warm armchair. It also offered traction on other examples: Robert Lowell’s account in “For the Union Dead” of pressing himself (in memory) against the long-gone glass of the South Boston aquarium and also (in the present day) against the construction fence that has replaced it. I liked the way that in Ford’s account it was not the mind that split in two, but something that came between mind and world. That piece of bright glass—refractive or translucent or reflective—conjures up a world in which a coherent consciousness has to make a choice about its relationship to the world it finds around itself. Do I wake or sleep? becomes a different kind of puzzle: What kind of wakefulness is this? That is, what sort of waking dream or dreamy wakefulness can leave me looking out at a world that itself splits, offering me a view ahead of myself but also, simultaneously, a view over my shoulder into the house behind me, mirrored there on the bright glass? If the brave new world of movie cameras was likely on Ford’s mind as he wrote, so too was Plato’s cave.

That double vision aligns Ford’s piece in some ways with the more famous account of impressionism that Conrad offers up in the preface to The Nigger of the Narcissus: “the motions of a labourer in a distant field,” whose actions and object become momentarily legible, before “we forgive, go on our way—and forget.”4 But Ford’s image of the doubled glass also contains a second notion: the odd feeling that in looking through the glass into an invented world, you are also looking back into reflections that may be coming from right behind you. Implicitly, then, gazing into a made-up realm also means entering your own world, your own life, in a different way (that could be your very own reflection you see on the glass). An 1869 poem by Swinburne offers a subtly torqued account of experiences that lie neither in the world out there, nor in the mind that takes in that world: “Deep in the gleaming glass / She sees all past things pass.”5 This deep glass allows the viewing subject to inhabit a space of reflection and inward contemplation at once within and without our actual world. Conscious awareness itself may be something that takes place not so much inside one’s mind as within that gleaming glass.6

Different academic disciplines have over the years variously approached the problem raised by such “deep glass” moments. It would be hard to think of a scholarly field that does not require some paradigm to account for unexpected sorts of cultural or cognitive recombination that take place in a way that fails to fit neatly into an established order of knowledge. The English psychoanalytical theorist Donald Winnicott sketched out a “third area,” a realm of play neither precisely part of the everyday world nor entirely removed from it; the renowned medievalist Johan Huizinga’s Homo Ludens anatomizes the realm of “serious play” in which ludic rule-following rehearses the right life; anthropologist Victor Turner theorized a notion of threshold or “liminal ” moments of cultural transition; Roland Barthes created a suggestive category of “the neutral” that also points toward similarly suspended zones. The possibility of such problematic overlaps even informs recent developments in the history of science, as for example in Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison’s compelling account of the nineteenth-century rise of “objectivity” as a crucial scientific desideratum. Their influential Objectivity (2007) charted the rise of an aesthetic “willed willfulness” that in reaction makes the arts home to an explicitly antiscientific subjectivism. That analysis implicitly opened up for investigation a turbulent in-between zone, a range of situations neither entirely aesthetic nor entirely scientific, in which objectivity and subjectivity collide and collaborate.

James’s anatomy of the way the mind wanders, decides things, then returns to actuality with a jolt (“that might be, but meanwhile she was going on”) suggested that a closer look at narrative arts might help make sense of the various “third areas” social scientists have diagrammed. Over the centuries, ideas about semi-detachment have been emerging, developing, waning, and waxing in the practice of those who rely on the concept most: novelists, painters, designers, and filmmakers. So I focus my attention on artists who throughout their working lives were pressed by the constraints and possibilities of their respective media to explore the curious aesthetic states not accounted for in sociological, philosophical, and anthropological approaches to the space between absorption and distraction.

The first fruits of this project were a pair of articles about how semi-detachment was imagined in twentieth-century America. One started by remarking on the ways that Edmund Wilson and others of his milieu started to think about suburbia as a semi-detached space, and ended with the Ang Lee’s vision of chilly Nixon-era Connecticut in The Ice Storm. The other made the case for thinking of social life as inherently semi-detached, in part by exploring how David Riesman’s mid-twentieth-century denunciation of “other-directed” sociability in The Lonely Crowd had given way fifty years later to Robert Putnam’s celebrated attack on atomized America in Bowling Alone.7 In its final form, though, Semi-Detached focuses on the ways novelists, painters, and filmmakers between 1815 and 1930 understand and make use of the state of dual awareness that an artwork produces: to share and not to share a world with an artwork’s fictive beings. On the one hand (for reasons I explore in some detail in the conclusion), this project aims to make sense of artworks as they work their way through time, affecting different audiences in different ways, and appealing to (or appalling) present audiences for reasons that have everything to do with present-day situations. On the other hand, I have striven to take a serious look at how artists (novelists, painters, filmmakers) understood the constraints and the possibilities that aesthetic semi-detachment afforded: if you want to understand bricks, ask a brickmaker. Chapter 5, on the experimental novel, looks at James’s dictation notes for his late novels, which attest to his evolving ideas about the relationship between a novelist’s voice and the reader’s experience. In chapter 7, Conrad’s acute diagnosis of his friend H. G. Wells’s scientific romances helps me frame an argument about Wells’s use of the legacy of the realist novel to open up a brave new world of speculative fiction.

A colleague recently proposed thinking about semi-detachment as a new aesthetic technology. Although semi-detachment is a concept, rather than a set of tools, the “brickmaker” principle does shed some light on the impulse to see this as a story about emerging technologies: technological advances can be shaped by the demands of aesthetic forms; in turn, new technical possibilities (“affordances”) can shift ideas about the capacities of art.8 Buster Keaton used trick shots, sight gags, and unforeseen properties of the newfangled “story film” in ways that were shaped by how he imagined his audience’s semi-detached reaction to his storytelling. In order to know what to invent next, it helps to know what you are trying to convey to your audience: a principle that applies as much to the rise of free indirect discourse in the early nineteenth century as to modernist experiments (in prose or on film) a century later.

HOW HISTORICAL?

The project began with a twenty-first-century “eureka” moment on a scruffy overpass. Unsurprising, then, that its early days involved slightly feverish attempts to link Victorian ideas about reverie directly to iPhones, Facebook addiction, and virtual reality thought-experiments of the Neuromancer variety. In the years that followed, my approach grew more synchronic, asking what early nineteen-century Scottish writers James Hogg and John Galt thought about the rise of the short story, what effect Eliot’s experiments with satirical verisimilitude in Theophrastus Such might have had on Henry James or even H. G. Wells. In fact, one virtue of focusing on the end of the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth has been to clarify the historical antecedents for the current upheaval in thinking about states of partial absorption.

So how historicist does this book aim to be? Is Semi-Detached anatomizing a durable mental state and the artworks that record its nature; or is this a systematic register of formal techniques, committed Quentin Skinner–style to strictly delimited, historically contingent registers of possible meaning?9 Much more the latter than the former—though I explain in the conclusion why that is a harder question to answer than it initially appears. Semi-Detached aims to map the range of “actor categories” that help explain the choices, even the compositional strategies of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century writers and other narrative artists—the logic that makes those artists deliberately turn to certain forms, techniques, and storytelling strategies that generate, or that represent, the state of semi-detachment. It tracks an unfolding conversation, sometimes explicitly marked, between Victorian and early modernist artists who understood their work as somehow tapping into, amplifying, or giving shape to a suspended duality of experience: the kind of duality Eliot depicts with elbows on bridge and armchair both, that James captures with his dialogue of the deaf between Marie Gostrey and Ralph Strether, that Ford Madox Ford describes by way of his double-layered glass, and that H. G. Wells approaches by way of “extra-dimensional worlds” at the very edge of tangibility and plausibility.

My presumption throughout has been that tracing semi-detachment as it materializes in past and present aesthetic forms does not prevent making contextual distinctions and exclusions. In Jane Austen’s Persuasion, for example, Wentworth writes Anne a note while he is listening to her talking with Harville about woman’s constancy in hopeless love. Is this a moment of involuted semi-detachment like that experienced by the Mill on the Floss narrator, whose arms rest on a stone bridge and his chair simultaneously? No. The crux in Eliot is not so much that a character is shown multitasking, but that the novel reflects on what it feels like to be partially drawn into a represented or imagined world while partially remaining at home in one’s own actual surroundings. The logic of selection turns on that question of how explicitly and overtly problems of doubled consciousness come to the fore. Austen notes the bifurcation—Wentworth is writing and listening both—but it does not lead her to the kind of speculation about here-and-thereness that becomes an overt topic of concern in novels like Mill on the Floss.

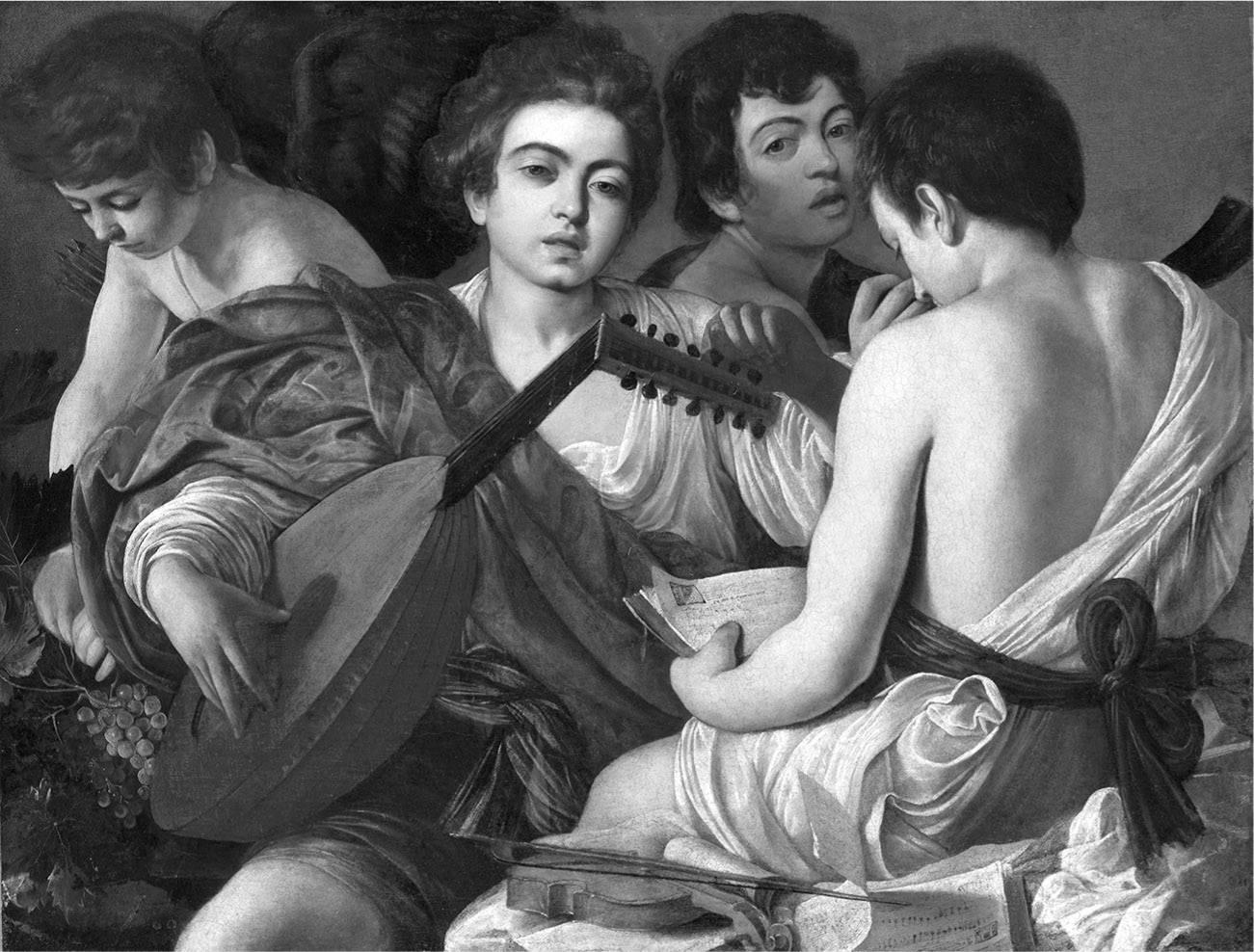

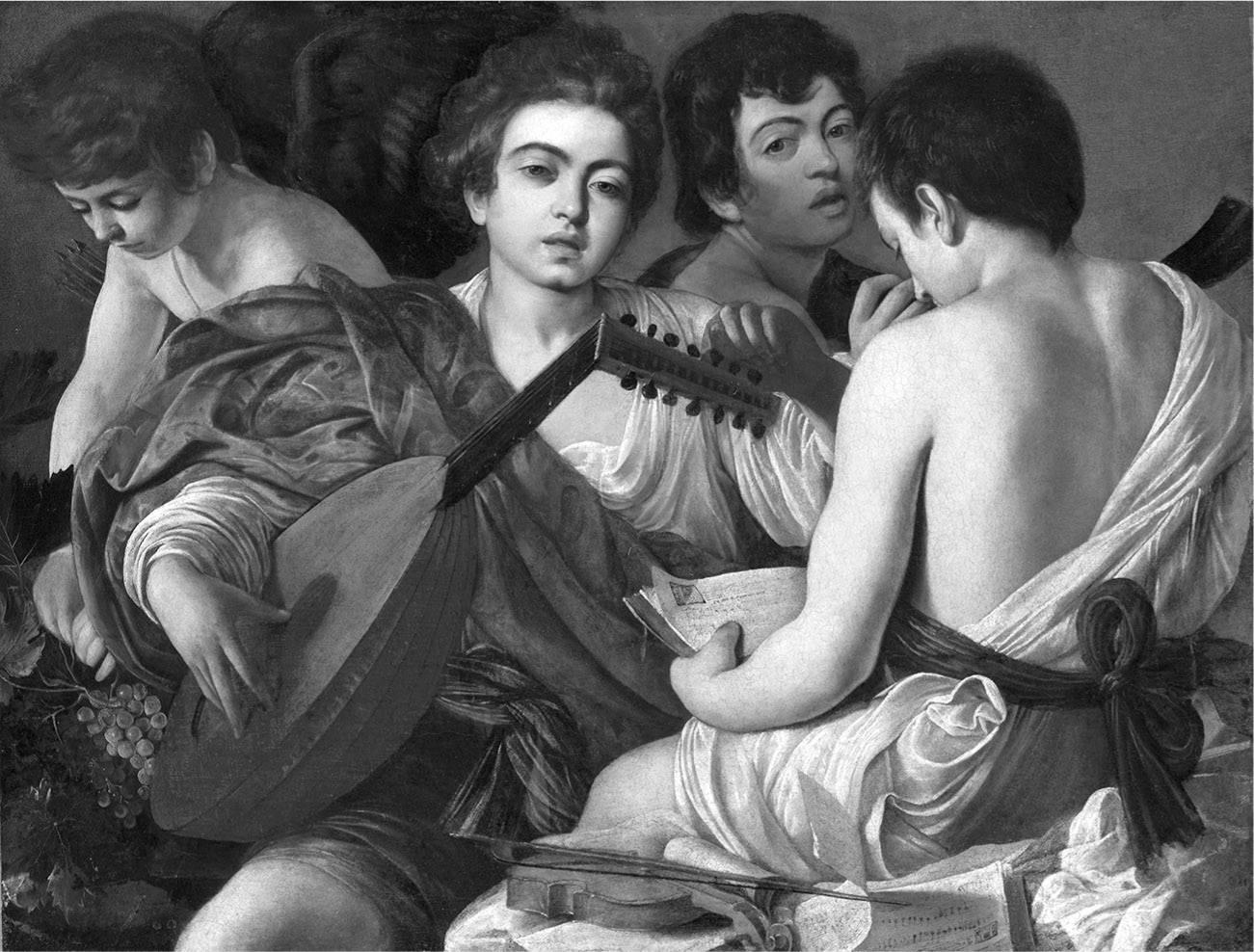

Still, historically minded genealogy should not become a sterile exercise in conjuring up a definitive past-as-it-must-have-been. Scott invented Dr. Jonas Dryasdust so readers could laugh at pedantic antiquarianism and academics might heed the warning: go thou and do otherwise. Presented only as a slideshow of a century’s worth of potentially semi-detached aesthetic moments, the chapters that follow would be of little help in constructing a general sense of the concept and its wider implications. Even the most dogged historicism should aim to shed light on a concept’s relevance outside a single era. The first time I saw Caravaggio’s 1595 The Musicians, I was struck by how its central figure seems to be gazing directly out at the viewer—but also blindly tuning, listening to the unheard music of his mandolin (Fig. 0.1).

What good would my genealogy be if it left no space for such disturbances and anomalies, for speculation about semi-detachment in Shakespeare’s reverie-laden Winter’s Tale, or in Le Roman de la Rose, or Virgil’s Eclogues? Not to mention the games with partial absorption that Cervantes’s Don Quixote plays: Quixote the dreamer seeing giants, and Sancho Panza by his side seeing windmills, with the result that readers are gifted with a kind of second sight and can see both at once.

FIGURE 0.1. Caravaggio, The Musicians (c. 1595, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). Courtesy of Bridgeman Images.

HOW LITERARY?

That kind of untimely meditation ultimately made it easier for me to think about looking farther afield for a general explanation of the doubling of experience, the two-in-one sensation, betokened by those Mill on the Floss elbows. The experience of semi-detachment is neither categorically nor exclusively a fictional one, and its attempts to think through its implications are not confined to a single genre, form, or medium. David Summers’s recent notion of the “double distance” produced by paintings, for instance, offers one fascinating way into the problem of semi-detachment. By his account, paintings implicitly instruct their viewers to respond to them both as material objects in actual space and as representations of a virtual world. The doubleness of the painting (it occupies actual space and creates virtual space) thus becomes an indispensable part of the conceptual encounter that viewers will have with it. Summers’s argument helped me to understand why I found the sightless gaze of Caravaggio’s musician so compelling. I saw him at the painting’s center, at once soliciting my gaze and gazing past me, as it were, staring at the (invisible and inaudible) music his fingers made. But I also saw something that could never, by definition, meet my gaze: pigments arranged on canvas by a long-dead painter. In short, I felt like that narrator from Mill on the Floss, thinking that my elbows were one place, only to give myself a shake and discover that I and my elbows were actually in another room altogether. Nothing but paint on canvas all along. And yet that gaze, and those tuning fingers, call into being a moment of intense intimacy. The moment Caravaggio’s musician acknowledges he is on one side of the pictorial divide and we are on the other is also the moment that heightens our sense of what kind of intimacy could exist between us.

Semi-Detached aims to imitate Caravaggio: to slow things down, to offer a complex account of what might otherwise be categorized in a way that captured only one side of an innately double experience.10 Thinking about the twin effects of Caravaggio’s painting helped me appreciate that Summers’s notion of “double distance” aligns with the Kantian notion of the aesthetic as a site where reflection and reception necessarily converge (which is at issue as well in John Stuart Mill’s conception of mediated involvement with his correspondents, readers, and collaborators). All three Visual Interludes benefited from the realization that it was not only novel readers who experienced an artwork’s capacity to make actuality partially recede. The doubleness that artworks produce in their deliberately imperfect virtuality was central to my exploration of Pre-Raphaelite struggles in a photographic age, to paint a not-always-objective “truth to life,” as well as to my account of William Morris’s efforts to turn his Kelmscott books into not-quite-self-contained little universes; central as well to making sense of Buster Keaton’s semipermeable film-world, which somehow seems simultaneously to exist up on a screen and in the viewer’s actual experience.

“Double Visions: Pre-Raphaelite Objectivity and its Pitfalls” moves into the mid-nineteenth century, examining a range of mid-Victorian paintings that explicitly or implicitly take semi-detached states of attention as their subject. The chapter explores what it means to be drawn into a painting’s world, and yet also to remain apart from that world—to be critically detached and immersed simultaneously. It begins with controversial Pre-Raphaelite paintings of the 1850s, which angered Dickens and others by insisting on changing the rules by which their realism was established. Such paintings, John Everett Millais’s 1850 Christ in the House of His Parents prominent among them, locate their putative actuality at one special moment in time—yet also openly acknowledge and reflect upon their dislocation from that time, the painting’s role as an artificial moment. The way that paintings by Millais and by Lawrence Alma-Tadema explore that tension sheds light on a problem that runs through nineteenth-century narrative art, as well.

“This New-Old Industry: William Morris’s Kelmscott Press” begins on November 15, 1888, when William Morris went to a “lantern lecture” by the skilled typographer Emery Walker, who screened a series of brilliantly colored photographs of books from the early days of movable type. Understanding why Morris was inspired that night to found the Kelmscott Press requires grasping what we might call Morris’s emergent residualism. Morris’s aesthetic practice in the 1890s, especially at the Kelmscott Press, bespeaks his commitment to creating innovative aesthetic experiments by recapturing long-lost artisanal practices that in their own day had been innovations that looked backward for inspiration. Recent work by Isobel Armstrong, Leah Price, and Elizabeth Miller on what might be called Victorian “materiality in theory” offers insight into the relationship between those glowing lantern slides of letter-forms and the solidly ink-and-paper books Morris brought into being. Those new accounts of how materiality was theorized in the nineteenth century also shed light on the tension woven into Morris’s work between what he called the “epical” and the “ornamental” aspects of a printed book.

Finally, “The Great Stone Face: Buster Keaton, Semi-Detached” traces the rapid emergence in the 1920s of semi-detachment in a new medium: building on theatrical, fictional, and painterly antecedents but strikingly original. Postmodern critical accounts highlight Keaton’s Borgesian games with film—and who could forget the moment in Sherlock Jr. in which Buster leaps out of a darkened movie theater into the film he is watching, taking on a new persona in the process? Yet such accounts underestimate the persistent complexity of the ways that Keaton’s characters essentially move in and out of touch with the world around them, attending and disattending to its actuality. Like Henry James’s notion of “disguised and repaired losses” and “insidious recoveries,” Keaton’s way of locating himself within “worlds not realized” offers his audience members insight into the yawning differences between what they initially grasp of the world around them and what may actually be going on just beyond their attention’s edge—unperceived but nonetheless real.

Visual Interludes and post-Kantian struggles with aesthetic judgment notwithstanding, the weighting of the chapters that follow signals the centrality of the genre of the novel and the formal possibilities afforded by fiction. However, proportional page weighting does not tell the whole story. The capacities of various visual media—from Pre-Raphaelite painting to silent film—to narrate is a key element in explaining how their audiences remain at once absorbed and critically detached. Conversely, works of fiction have a spatial as well as a temporal dimension, and that doubleness is decodable; indeed, it is part of the story that novels themselves tell about their own formal status.

The crucial overlaps come into sharp focus only when the elective affinities between the novel and the experience of semi-detachment are mapped. For that, two recent accounts of realism in fiction prove exceptionally helpful: Catherine Gallagher’s idea of novels arising in the eighteenth century as “believable stories that do not solicit belief”11 and Franco Moretti’s proposal that we think of the realist novel as ineluctably constituted out of sequences of episodes.

BELIEVABLE AND INVENTED

Catherine Gallagher’s influential work, from Nobody’s Story to a recent summative piece on “The Rise of Fictionality,” stresses the importance of eighteenth-century market conditions (a worldview shaped by “disbelief, speculation, and credit”) in shaping novels into “believable stories that do not solicit belief.”12 Gallagher proposes that “readers attach themselves to characters because of, not despite their fictionality. . . . Consequently we cannot be dissuaded from identifying with them by reminders of their nonexistence.”13 Another way to put Gallagher’s claim is to say that the very thing that makes the experience of characters especially congruent to us as readers—that we can overhear or learn of their thoughts, especially via free indirect discourse—is also what makes clear their dissimilarity from us. With believability their benchmark and inventedness their given, novels do two seemingly discordant things simultaneously. On the one hand, they allow for a form of imaginative escape, a release into the pleasures of an invented world—the travails of a fictional character require no direct action on the reader’s part. On the other, they trigger experiential attentiveness to the way the world is.

Readers of realist novels principally respond to fictional characters in their innately doubled roles as simultaneously plausible inhabitants of a world just like ours, and as thoroughly airy products of mere textuality. Compare this account of fictionality’s dual nature to Michael Saler’s recent As If, which makes the case that we should understand realist fiction as an imperfect way station on the path toward fully immersive art.14 Saler argues that full-on dream worlds—modern-day virtual gaming worlds and in series like Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings—achieve the fondest hopes of past fictional realism: Sherlock Holmes ushered his readers into an era of “disenchanted enchantment” or of “animistic reason,” so that the late nineteenth and early twentieth century became a golden age for the plausible invented universes that Tolkien labeled “secondary worlds.”15 If Saler reads fiction as an attenuated version of fully immersive fantasy (“subcreation”), Gallagher makes clear the benefits that accrue to novels precisely from the doubleness of fictionality. Semi-detachment marks just that doubleness.

What looks like a contradiction between the novel’s commitment to capturing social reality and its interest in the experience of psychological depth is actually productive complementarity. 16 Like characters, we have inward thoughts and experiences that do not directly appear in the world outside us; unlike us, they do not truly have such thoughts because they are characters and not persons. Think of Jane Eyre, reading for life in a window seat, screened from and yet connected to a cold world beyond the glass: she is also cousin Jane, aware that at any moment the red curtain will be thrown back and her book turned into another weapon in a daily domestic war. The Jane who contemplates the glories of the world of Roman history opened up in the talk (and inside the glowing temples) of Helen Burns and Miss Temple is also the Jane blissfully aware of what it is like to be well-fed and ensconced within the only “temple” to be found in profane Lowood. In the world Brontë envisions, books can as readily turn into a missile to strike her readers as they can serve as an escape hatch to another world.17

Semi-Detached spends considerable time tracing the implications of Gallagher’s model of cognitive suspension and fictionality. “Experiments in Semi-Detachment” charts ways that realist novelists—Dickens, Eliot, and James especially—modify formal techniques such as free indirect discourse in an effort to make sense of the way that consciousness, in life as in fiction, can be located in more than one place simultaneously. The flickering, moving center of consciousness charts novelists’ efforts to understand that fraught and ironic capacity to see one’s life from one’s own perspective and also from outside. Henry James, for example, aims to render an unstable equipoise between—to borrow terms Lukacs uses to distinguish between realism’s interest in narrating subjective interiority and naturalism’s attachment to the “mere facts” of the world—the world as event and as experience. James sees the novel’s distinctive capacity in its movement between what he calls “dramatic” (event-oriented) and “representational” (experience-oriented) prose.

“H. G. Wells, Realist of the Fantastic” follows the same line of thought, arguing that Wells’s decade of experiments with the genre of “scientific romance” signals a fin-de-siècle turn away from many of the normative assumptions of Victorian realism; he does so by examining curious cases in which characters undergo extreme experiences, while simultaneously remaining anchored enough in the actual world that their stories can somehow be recovered and transmitted. Conrad’s label for Wells—“O Realist of the Fantastic”—is a useful reminder that Wells profited from the elaborate unfolding of new formal capacities in late Victorian realist fiction. Wells’s experiments in double exposure speak not to a broken world, but to a glitch in how that world enters into consciousness. Between the wars, a range of writers from Dunsany to Kipling to Forster to Stella Benson—practitioners of what Adorno disparages as “moderate modernism”—produce speculative fiction made possible by those formally simple but conceptually innovative stories of Wells.

By the same token, “Overtones and Empty Rooms: Willa Cather’s Layers” sets out to track Cather’s idiosyncratic movement away from antecedents ranging from Norris’s naturalism to James’s novels of consciousness toward a “moderate modernist” form of semi-detachment. Her fiction between O Pioneers! (1913) and The Professor’s House (1927) turns away from the possibilities explored by Lawrence, Hemingway, Woolf, Proust, Joyce, Faulkner, and Fitzgerald, seeking instead moments of aesthetic translucence, the overlay of one image, or one sound, on top of another. Such moments of overlay (or overtone) encapsulate the problem, as well as the promise, involved in turning one’s readers simultaneously into participants and critical witnesses to one’s story. Cather’s distinctive form of modernism hinges on the way that she postulates a dichotomy between the world of aesthetic dreaming and the world of hard facts—then asserts fiction’s capacity to inhabit both simultaneously.

EPISODES AS (AND AGAINST) PLOT

Gallagher’s account of fictionality elucidates one key component of the experience of semi-detachment: readers’ knowing embrace of artifice as if it were real. Her account highlights the ways in which fictionality implicitly works to separate the experience of reading fiction from the experience of actuality: of life lived inside the real world rather than in the pages of a book. Yet the link between Gallagher’s concept of fictionality and the experience of semi-detachment does not foreclose ties with other critical accounts of the realist novel, among them Franco Moretti’s argument about the “episodic” nature of fiction. The “episodic” is by Moretti’s account both that which interrupts the flow of important events inside the European nineteenth-century realist novel—and also as, mirabile dictu, the actual substance out of which those events are constituted: “Small things become significant, without ceasing to be small; they become narrative, without ceasing to be everyday.”18 Moretti sees the novel representing actual life, that is, by capturing the way that any such life is built out of a series of single events or scenes. Taken each on their own, such episodes are trivial. When a character or a narrator looks back seeking order, however, those little pieces of almost-nothing can be sequenced together—strategically or arbitrarily excised, or newly arranged and ordered in the retelling—to add up to something much larger. 19

The capacity to go back into the past to resurrect old occurrences and recognize their new significance in light of the present may not seem at first blush much like the capacity to feel oneself at home within a fictional world and actuality simultaneously. But—as modernist novels influenced by Henri Bergson’s ideas about involuntary recall explored in exquisite detail—the discovery that one’s past accompanies one in the present may manifest itself as the experience of living inside two worlds at once. For a novel to be made up of episodes, aggregated actions that may or may not matter in the grand scheme (or that matter at one point and then cease to matter) has the odd effect of creating an immanent semi-detachment. Because every event in one’s life is important not only as it occurs but also as it is retrospectively called up and made part of a series or pattern of events, the very fact of one’s present experiences is itself shot through with a sense of absent events: the facts of the past or of the future that will make this event sequentially significant.

Novels, then, are constituted out of episodes agglomerated into a plot that nonetheless retains its contingent relationship to those disaggregated episodes. This opens the door for readers to understand their own relationship to their actual past similarly. Saler’s notion of fiction as normatively aspiring to create a “secondary world” (a self-contained fantasy space apart) misses just such inklings, which are woven into Gallagher’s account of fictionality’s cognitive complexity. The looseness in the relationship between any given episode and the overall plot of a novel is a crucial form of semi-detachment.20 Just as the impressions that Ford describes seeing in a half-darkened glass are double, so too do episodes, in this laminated account of the dialectic between past and present, loom into view as bygone events that are brought back into a kind of significant pastness by events of the present. Fiction’s episodic nature—which allows the narrative partially to pull away from present surroundings to recollect the past—allows it to be mimetic of the real-world experience of discovering oneself overcome by what’s bygone. Bulstrode’s hidden nefarious past in Middlemarch, a past that will destroy him once known, is only revealed by actions occurring in the novel’s present. Revealed, it becomes part of the novel’s present—but as something long gone, present and absent both, evident in its very evanescence.

“Pertinent Fiction: Short Stories into Novels” relates crucial developments in nineteenth-century British fiction—the decline of the romantic tale, the rise of the short story, and the short story’s subsequent shadow-life within realist novels—to changing ideas about semi-detachment. The relationship between the “real”—circumstantially vivid, experientially centered and particularized—and the “true”—the timeless, incontrovertible, and generalizable—changed markedly in both short- and long-form fiction in ways that have everything to do with new ways of thinking about readers’ absorption, or partial absorption, into a fictive world. The chapter tracks the hybrid and disruptive form that tales and stories took in romantic-era writers such as James Hogg, as well as the rise of the sketch and the short story (exemplified by John Galt’s late work) in 1830s Britain. When short stories are absorbed into the “baggy” long-form Victorian realist novel, what might seem like narrative detours, digressions, or pure interpolations are instead made pertinent to the novel’s characters.

The uneasy relationship between episode and whole—and analogously between the local and the universal—plays a similarly important role in “Virtual Provinces, Actually.” That chapter asks how novelists from Gaskell to Trollope to Margaret Oliphant think about provincial subjects as existing both on the margins of a society centered elsewhere, and also as necessarily centered in the delimited sphere of their own experience: thus, a life that is simultaneously peripheral and central. At the heart of the provincial novel lies not a triumph of the local over the cosmopolitan (Little-Englandism), but a fascinating version of magnum in parvo, whereby provincial life is desirable for its capacity to locate its inhabitants at once in a trivial (but chartable) Nowheresville and in a universal (but strangely ephemeral) everywhere. Margaret Oliphant’s searching accounts of irritation and envy as provincial vices, in such undervalued works as The Rector’s Family and The Perpetual Curate, chart that Nowheresville’s boundaries.

BETWEEN WORLDS: THE ADVANTAGES OF FUZZINESS

There are organizational disadvantages to a book about an idea with as many edges as semi-detachment: genre boundaries, historical periodization, and even disciplinary logic all potentially militate against any cohesion. Describing this project as aligned with Gallagher on believability or with Moretti on the episodic is not the same as claiming for it a thoroughgoing historicism, or a consistent commitment to mapping decade-by-decade change. Moreover, the book concludes by reflecting on the inevitable influence of present conditions on any scholarly account of the past, this one very much included. Yet the aim is unitary: to examine across genres, decades, and disciplines a single phenomenon, albeit one with fuzzy borders. My hope is not so much to dispel as to examine that fuzziness, to explain (rather than explaining away) semi-detachment as a phenomenon that artists reflect upon and represent in their works, and as something audiences experience at the moment of aesthetic encounter.21

In “Apparitional Criticism,” I conclude by turning the lens of semi-detachment on the scholarly undertaking itself. Historically informed scholarship strives to avoid, on the one hand, antiquarianism (the past as a world viewed with precision and certainty through a telescope) and, on the other, pure presentism (conceiving of the past as always knowable only on the present’s terms). However, a problem that already preoccupied writers like Scott and Browning persists today: what is the relationship between our own conception of the past as past and what that past must actually have been like as a present? My own effort at “reading like the dead” (detailed in the conclusion) helped me understand both the pitfalls and the promises of any backward leap. Semi-detachment proves a vital concept in making sense of the gulf, neither imaginary nor impassable, that yawns between ourselves and what has gone before.

In The Four-Dimensional Human, Laurence Scott reports on the humiliation of being caught texting in a bar while pretending to listen to his tablemates. He repents “my puncturing of our sociability, the bleeding away of presence.” Yet he also discovers the pleasures of “shimmering between two places, living simultaneously in a 3d world of tablecloths and elbows, and also in another dimension, a lively unrealizable kind of nowhere, which couldn’t adequately be thought about in the regular terms of width, depth and breadth.”22 Scott ends his book with a call for “refreshing two-mindedness . . . a spacious habit where the unknown parts of ourselves and others are allowed to shimmer in their uncertainty, a humane, unmappable multi-dimensionality.”23

This book makes the case that unmappable multi-dimensionality has been available for quite some time. In the 1890s, the “slow print” movement of the day was declaring the high-speed printing press a force every bit as terrifyingly revolutionary as the iPhone seems today; and H. G. Wells was not the only writer to conjure up worlds of n-plus-one (or n-minus-one) dimensions in which everyday rules went out the window. John Stuart Mill’s agonized correspondence with Carlyle about his failure at face-to-face intimacy compared to the bliss he finds in print; George Eliot’s account of the way that Dorothea’s mind wanders away as she contemplates insect parliaments: when have we not been semi-detached? iPhones may electronically amplify our ways of being, but “shimmering in uncertainty,” or “entering a lively unrealizable nowhere”? Eliot’s been there, Buster Keaton’s done that.

As a kid, I was fascinated by a forest glade, filled with shallow pools, that appeared midway through C. S. Lewis’s The Magician’s Nephew. It kept me up at night not by its other-worldliness, but by what you might call its quasi-worldiness: it was “the wood between the worlds.” The book’s protagonists, Diggory and Polly, appear there when they touch his evil uncle’s magic rings; when they master the wood’s secret, they can reach Narnia. What enthralled and terrified me was Polly and Diggory’s dazed, stumbling progression from shallow pool to shallow pool—especially the fact that they almost forgot to mark the one from which they had emerged, the one and only way back home to their own world.

The fascination of that wood between the worlds may seem to have a name that comes straight from Coleridge’s idea of the “suspension of disbelief”: absorption. Not quite. In The Magician’s Nephew, Diggory’s uncle thinks of the yellow ring as what takes you out of the actual world and the green ring as what brings you back. But the children understand a crucial distinction: a yellow ring actually takes you to the wood between the worlds, while a green ring sends you back out into any of the myriad available worlds. The wood’s appeal to me (or its terror) lay in the idea of a between space, where both reality and fantasy were held temporarily in abeyance.

We should not underestimate the halfway-thereness that aesthetic experiences allow us to approach, explore, and comprehend. Even in a world of play-anywhere online gaming and “continuous partial attention,” a world in which tirades about cyber-dependency compete with the allure of augmented reality, entering imaginatively into virtual worlds remains a complex undertaking with both payoffs and pitfalls that have to do with far more than leveling up, or tuning out. What I loved as a child was not losing myself; it was being at once lost and found. I went out and back in again, treating every world like a shallow pool: reality included. This is a book about such in-and-out experiences—and what difference they should make to our ideas about aesthetics.