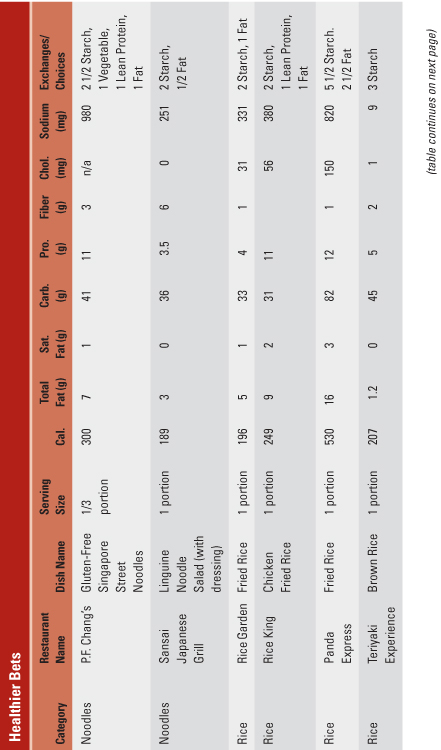

Chinese food ranks in the top three of Americans’ favorite ethnic cuisines. While Chinatowns in major cities are one place to find Chinese food, today it’s common to see Chinese restaurants in shopping malls and urban, suburban, and rural neighborhoods. Some of these restaurants have tables for eating in, as well as plenty of containers for takeout. Others offer only takeout. Many Chinese restaurants are single, family-owned establishments and reflect the foods typical in a specific region of China.

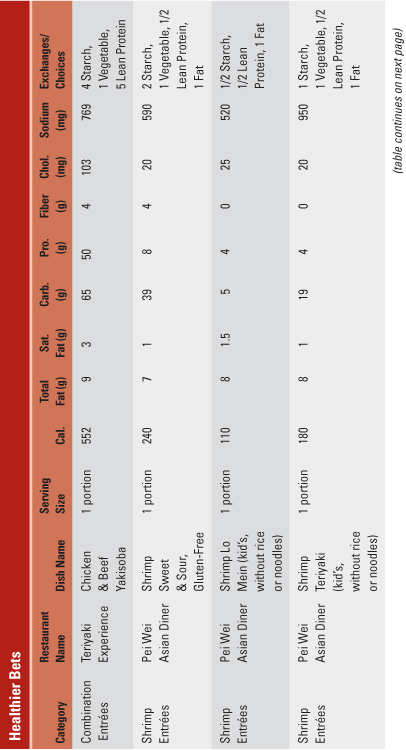

There are currently only a handful of national Chinese food chains. Typically, these chains offer a more Americanized version of Chinese food than independent restaurants. Panda Express, the largest national chain serving Chinese food, can be found in food courts, airports, casinos, and even in the food courts in the Pentagon, just outside of Washington, D.C.

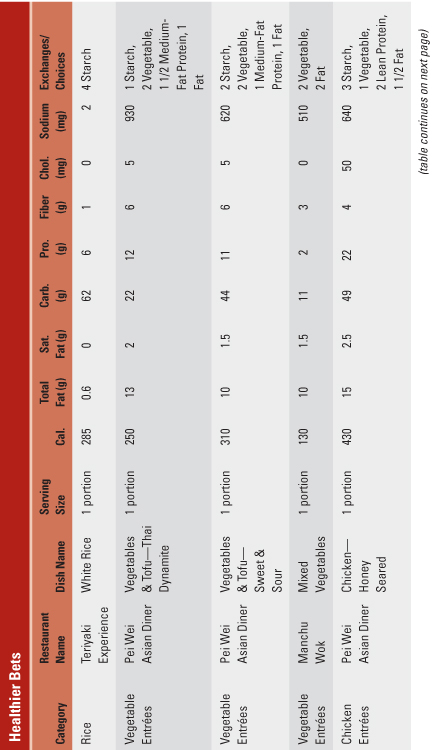

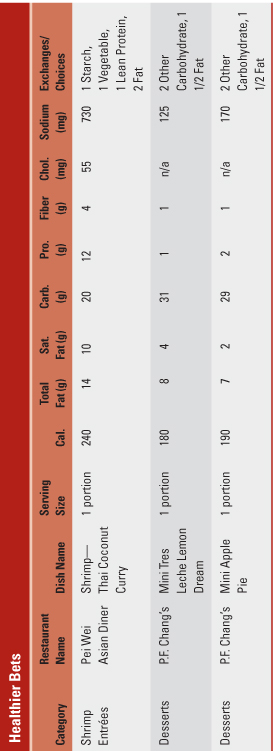

Today, due to the increasing popularity of other Asian cuisines, Panda Express has integrated a few Thai, Japanese, and Vietnamese dishes into their menu, so it’s no longer purely Chinese cuisine. Two other fast casual Chinese chains on the rise are Pei Wei Asian Diner, which offers dishes from a variety of Asian cuisines, and a relatively small Minneapolis-based chain called Leeann Chin. If you’re looking for upscale Chinese restaurants, P.F. Chang’s China Bistro (locations nationwide) and Big Bowl (locations in Chicago, Minneapolis, and Washington, D.C.) offer sit-down service and an array of Chinese and Thai dishes.

There’s also a crop of Mongolian barbeque restaurant chains, in which a waiter serves you but you make a trip (or unlimited trips) to a food bar to pick out your own ingredients, which are then stir-fried on a large grill by a chef. Despite the Mongolian name, this type of cooking is believed to have originated in Taiwan, China. Great Khan’s, Genghis Grill, BD’s Mongolian Grill, and Flat Top Grill are four of the chains that offer this type of cuisine.

Chinese dishes, such as stir-fry chicken, vegetables, and chop suey, also show up on many family and American-style restaurant menus, but you’ll find these dishes discussed in this chapter. Chapter 22 will give you a more in-depth look at Thai cuisine and Chapter 23 covers Japanese cuisine.

![]() On the Menu

On the Menu

Chinese foods, markets, and cooking styles were virtually unknown in America prior to the mid-1800s. Initially, when people from China came to the United States, it was common for them to settle in enclaves that became known as Chinatowns. Well-known Chinatowns were located bi-coastally—in Boston and New York and in Los Angeles and San Francisco. The streets of Chinatowns were (and still are) dotted with restaurants and bakeries where you can enjoy a sit-down meal or grab a quick order of pork buns.

Though Americans initially became accustomed to eating only Cantonese-style Chinese food, today Chinese restaurants serve cuisines from various regions of China, such as Szechuan, Hunan, and Peking (Beijing). Many times, dishes on a Chinese menu will be named for the particular region from which the cooking method originated. Examples are Peking duck, Szechuan spicy chicken, and Hunan crispy beef. Opinions vary as to whether China actually has three, four, or five regional cuisines, but in reality, if you consider all the subtle regional differences the food can reflect, there are many types of Chinese cuisine.

Interestingly, Chinese cuisine wears a halo of health because people think of Chinese food as heavy on vegetables and light on fat. This perception may be true when foods are prepared traditionally or in China, but it’s not true when most Chinese foods are prepared in America. The Americanized preparation methods often mean added fat, fried noodles with soup, fried appetizers, and battered and fried meats (shrimp, pork, chicken, beef) in dishes coated with sweet sauces. Keep this in mind when you order and try to eat more vegetable-dense and traditional dishes.

The fat content of many Chinese dishes is one of the main roadblocks to eating healthfully at Chinese restaurants. However, it’s easier to limit the amount of fat in dishes at Chinese restaurants than at family-style American restaurants. Special requests—which are easy to make because the food, at least in sit-down Chinese restaurants, is generally prepared to order—will help you limit the fatty ingredients, added oils, and high-sodium and thick, sugary sauces in your meal.

What types of fat are used in Chinese cooking? Traditionally, lard (pork fat) was used. Thank goodness healthier liquid oil is generally used today. Peanut oil is commonly used because of its high smoking point, not its health quotient, but it’s reasonably healthy too. Peanut oil gives a slightly nutty flavor to dishes. It is mainly a monounsaturated fat, which is thought to help lower bad blood cholesterol (LDL). Sesame oil is also used, but in smaller quantities. Sesame oil is a polyunsaturated fat, which also assists in lowering blood cholesterol. The oils used in Chinese cooking are generally healthy, but the problem is excess use.

The most common Chinese cooking method is stir-frying in a wok (a common bowl-shaped cooking vessel). A wok can also be used for other cooking methods, such as braising and steaming. Wok cooking can be quite healthy. A minimal amount of oil can be used, and foods are cooked only briefly, so they retain their much of their vitamins and minerals.

One other health villain is the high sodium content of Chinese food. Many dishes contain high-sodium soy sauces, light and dark, and monosodium glutamate (MSG). MSG is the sodium salt of the amino acid glutamic acid. It’s approved for use by the FDA and is used in foods as a flavor enhancer. It contains about one-third of the sodium in salt. Other sauces such as oyster, black bean, and hoisin (or plum sauce) also contain large amounts of sodium. For a frame of reference, 1 tablespoon of soy sauce has about 1,000 milligrams of sodium.

A few special requests can quickly decrease the sodium content of your meal. You can request that the kitchen use less soy sauce and no MSG in your dish. Many Chinese restaurants today note on their menu that no MSG is used. Do not try to eliminate soy sauce or sauces altogether because the end product simply will not be tasty. You don’t want that. There is a happy medium! Think about using hot oil, chile sauce, or hot mustard as low-sodium flavorings to add some zip to your food. All things considered, however, Chinese food might not be the optimal choice, at least on a frequent basis, if you need to keep your sodium intake in check.

Another important note: people with diabetes often find that Chinese food can wreak havoc on their blood glucose levels. That’s not a surprise. There are hidden grams of carbohydrate in Chinese foods, from the sugar in marinades for meats to the cornstarch that’s used to thicken dishes in the wok. Then there are high-sugar sauces, such as the sauce used in sweet-and-sour dishes, hoisin sauce, and the duck sauce on the table. Limit your use of heavy, potentially sugar-dense sauces. Request that the chef leave sugar and cornstarch out of your dishes if possible. (However, you may be told that these ingredients are already premixed into marinades or sauces.)

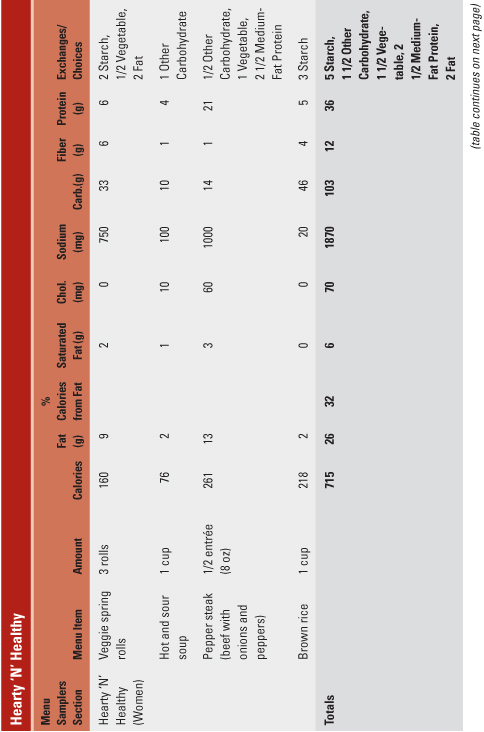

One of the biggest perks of eating Chinese food is that the common way of ordering and eating is family style, and sharing is ideal for people practicing portion control. Don’t feel compelled to order one dish per person. Order fewer dishes than the number of people at the table and get ready to share. Order protein-focused dishes and complement them with vegetable-focused dishes. This balance can help you meet your healthy eating goals.

Another plus is that vegetables are abundant in Chinese cooking. Be sure to look at the descriptions of menu items and cast your eyes on the vegetarian listings. You are familiar with many of the vegetables used in Chinese cuisine: broccoli, cabbage, carrots, mushrooms, snow peas, water chestnuts, bamboo shoots, and onions. Others vegetables on the menu may be less familiar, such as bok choy, napa cabbage, wood ears, and lily buds. For descriptions of these ingredients, see Menu Lingo at the end of this chapter. Load up on vegetables at Chinese restaurants, and try some unfamiliar veggies if you’re feeling adventurous.

Chopsticks are the eating utensils of choice in Chinese restaurants, though forks and spoons are available if you are not adept with chopsticks. However, lack of aptitude with chopsticks might be a blessing in disguise. A lack of dexterity can slow your pace of eating. So go ahead, be daring and use chopsticks, but put your napkin squarely on your lap to catch the misfires.

![]() The Menu Profile

The Menu Profile

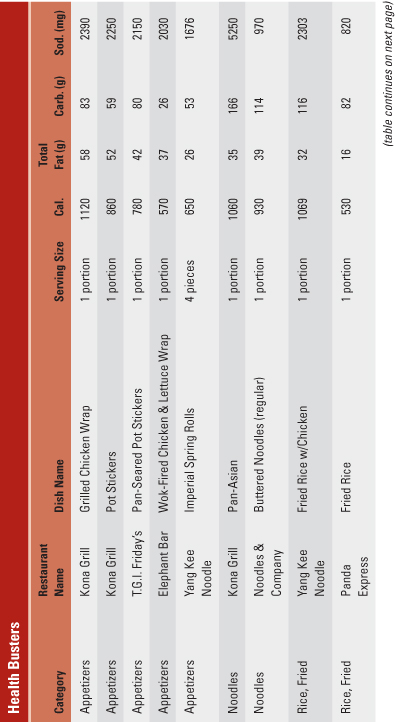

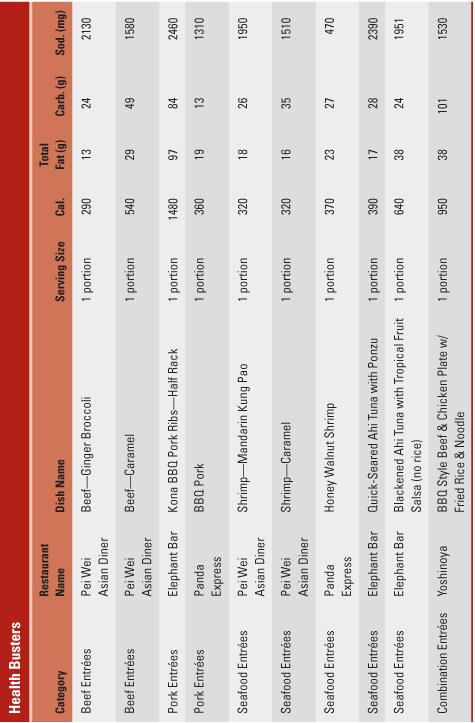

Appetizers

Decisions, decisions—it’s appetizer time. Many Chinese appetizers are simply off-limits to those who follow a healthy eating plan because they are fried or high in fat. The appetizers to avoid include fried noodles, fried shrimp, wontons, chicken wings, spareribs, and egg rolls, to name just a few. Some healthier appetizer options are spring rolls (fresh, not fried), steamed Peking raviolis (preferably vegetable or shrimp rather than pork), roasted pork strips, and barbecued or teriyaki beef or chicken (if sodium is not a big concern).

Soups

Think about skipping high-fat appetizers and filling up, instead, on a bowl of low-calorie broth-based soup, especially if your dining partners are indulging in high-fat appetizers. Notice that no creamy soups are served in Chinese restaurants. Hot-and-sour, sizzling rice, egg drop, or wonton soup are all healthy soups unless you’re watching your sodium intake. Like most soups, the soups you’ll find in Chinese restaurants are loaded with sodium. Hot-and-sour soup is likely the highest in sodium, and egg drop or wonton soup the lowest. Soup can take the edge off your appetite, fill you up, and help you decrease the total amount of food you eat over the course of the meal.

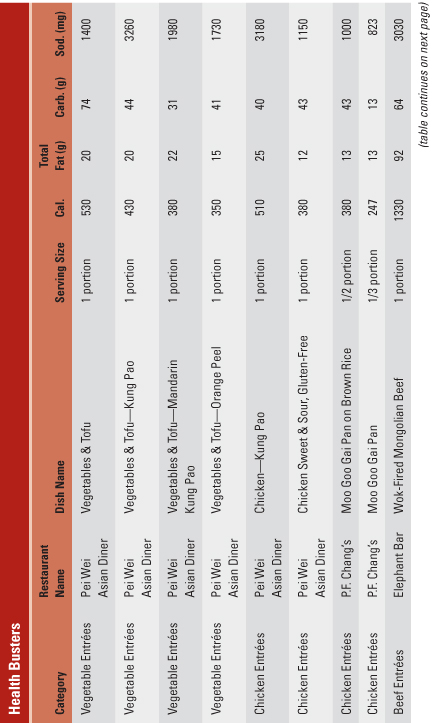

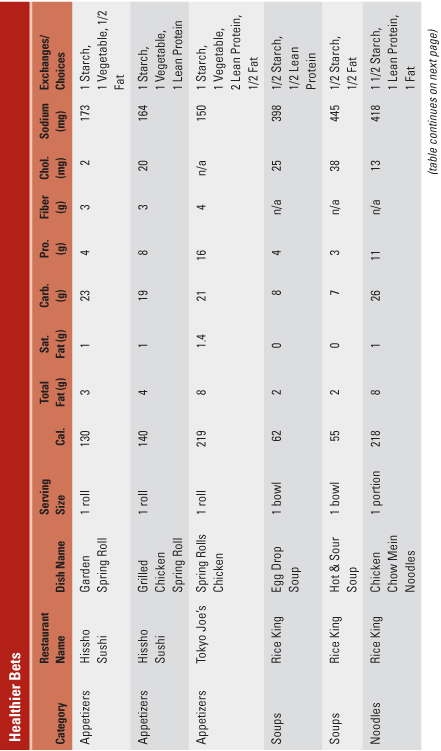

Entrées

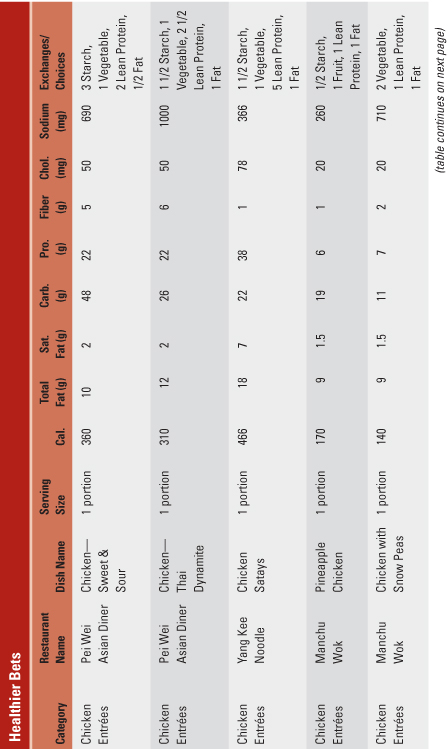

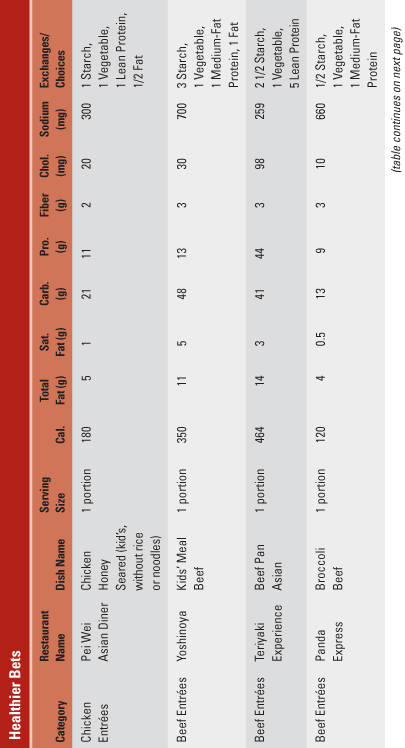

You’ll likely have a wide array of choices when it comes to the source of protein in your entrée, including beef, pork, chicken, duck, seafood, and tofu (bean curd). Beef, pork, and duck are typically higher in fat and calories than chicken, seafood, and tofu. But of course, preparation method matters. Just because an entrée contains a lean source of protein—or at least one that was lean before it was surrounded by batter and hit the deep-fryer—doesn’t mean the final dish will be healthy. Three popular chicken dishes, Kung Pao chicken, honey chicken, and General Tso’s chicken are often high in calories and fat, as the chicken is usually deep-fried. But don’t be shy about asking to have your protein sautéed instead of fried.

Likewise, shrimp, prawns, scallops, calamari (squid), and whole or pieces of finfish are common on Chinese menus. But read the menu descriptions with care. Much seafood is also battered and fried before it reaches your table.

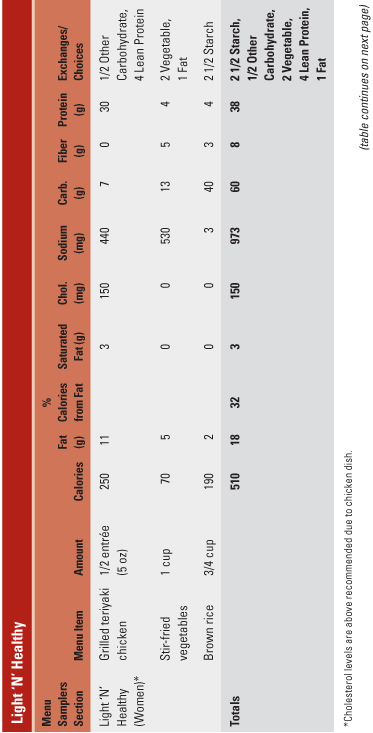

At Pei Wei Asian Diner, most entrées can be prepared in two ways: the traditional way (cooked in oil) or what they call “stock velveted," a method in which the source of protein in the dish is cooked (steamed) in seasoned water. This restaurant provides nutrition information for both the traditionally prepared and stock velveted (steamed) versions of each entrée, when applicable. To give you an idea of the difference that this small change in preparation method makes, it usually reduces the dish’s fat grams by half or more. If possible, try to get your dishes stock velveted in the Chinese restaurants you frequent to reduce fat grams and calories. Thanks, Pei Wei Asian Diner! Maybe other restaurants will follow suit.

In addition to the cooking method, you’ll want to pay close attention to the sauces used in or on the dishes you order. Sauces like sweet-and-sour, duck, and plum are thick, sugar-dense sauces that contain extra carbohydrate and should be used minimally. The same goes for menu items that are honey battered; they offer a double whammy of sugar and fat.

Always peruse the menu and look for dishes with lots of vegetables. You might find the words “assorted vegetables" or “broccoli and water chestnuts." If it’s not obvious, ask if the dish has vegetables and what types of vegetables are used. You can always request that extra vegetables be added to your dish. Another strategy is to complement a protein-focused dish with a vegetarian one. Try spicy green beans, spinach and garlic, or the vegetarian delight. However, make sure none of the items in the dish, such as the tofu, are deep-fried prior to being served. If an item is usually fried, ask for the item to be prepared in a different way. Skip Szechuan eggplant, which is loaded with fat.

At Mongolian barbeque–style restaurants, the biggest perk is that you have full control over your meal. As you assemble your dish, fill your bowl with plenty of vegetables. You’ll be surprised at how much they shrink down when cooked. Use your discretion when you ladle on the sauces. Flavored waters and spices are often available and are a healthful way to add flavor to your meal without adding sugar or lots of sodium. Your biggest red flag at this type of restaurant is the promise of unlimited trips to the food bar. Fill up on vegetables and lean sources of protein to help curb the temptation to keep returning. Then just fold your hands in your lap when you know you’ve had all you should eat.

Rice and Noodles

On to the starches: rice and noodles. Both are always available in Chinese restaurants in different forms. Some are healthy, some are not. Obviously, steamed brown rice is ideal, but it’s not available in many Chinese restaurants. Steamed white rice is more common. It’s steamed with no added salt or fats. Fried rice is white rice stir-fried (which adds oil) with soy sauce that turns it brown and adds sodium. If you order fried rice, stick with the vegetable variety and avoid the fat and protein added by pork or other meats. Similar advice holds true for lo mein and pan-fried noodles. Order these dishes with vegetables rather than high-fat proteins. The basic noodle is healthy, though it has very little fiber or whole grains, but the health quotient goes downhill as chefs add oils and high-sodium sauces. It’s easy to eat a lot of carbohydrate from rice and noodles, so eat only a small amount of these dishes.

Dessert

Dessert in Chinese restaurants is usually low key. Often, you don’t even order it. Pineapple, orange sections, or lychee nuts simply appear at the table with one fortune cookie for each diner. Desserts on the menu sometimes include ice cream or fried bananas. You are best off skipping menu desserts. And you’ll leave the table a bit healthier, and maybe wiser, if you read your fortune but leave the cookie.

![]() Nutrition Snapshot

Nutrition Snapshot

![]() Green-Flag Words

Green-Flag Words

Ingredients:

• Assorted vegetables (broccoli, mushrooms, onions, carrots, cabbage, bok choy, water chestnuts, bamboo shoots, lily buds, wood ears, bean sprouts)

• Bean curd (tofu)—sautéed, not fried

• Broth (for both-based soups)

• Chicken, roast pork

• Chile sauce

• Chinese hot mustard

• Chinese spices

• Fish, shrimp, scallops, squid

• Garlic

• Ginger

• Hot oil

• Pineapple

• Soy sauce (high in sodium)

• Tomatoes

Cooking Methods/Menu Descriptions:

• Brown sauce, oyster sauce, black bean sauce (these can be high in hidden sugars and sodium)

• Chop suey

• Chow mein

• Hot and spicy tomato sauce

• Light wine sauce

• Lobster sauce

• Moo shi (or moo shu)

• Served on sizzling platter

• Simmered or braised

• Slippery white sauce or velvet sauce

• Steamed

• Stir-fried with vegetables

![]() Red-Flag Words

Red-Flag Words

Ingredients:

• Cashews or peanuts

• Chinese noodles

• Duck with skin (typically served with skin)

• Hoisin sauce, plum sauce, sweet (duck) sauce (these can be high in hidden sugars and sodium)

• Water chestnut flour

Cooking Methods/Menu Descriptions:

• Battered or breaded and fried

• Crispy

• Fried, deep-fried, deep-fried until crispy

• General Tso’s

• Honey sauce, honey battered

• Kung Pao

• Orange peel or orange flavored (chicken, beef, etc.; all are deep-fried)

• Served in bird’s nest (which is fried)

• Spare ribs

• Sweet-and-sour

• Whole fish (usually fried)

At the Table:

• Chinese noodles

![]() Healthy Eating Tips and Tactics

Healthy Eating Tips and Tactics

• To keep sodium low, don’t dip appetizers in sweet (carbohydrate-containing) or soy-based (sodium-containing) sauces or limit their use. Hot Chinese mustard might be a flavorful option.

• Choose steamed white or brown rice rather than fried rice. Brown rice is healthiest when available.

• You’ll be better able to control your order if you choose a sit-down Chinese restaurant, where you can easily custom order, rather than one in a food court or an all-you-can-eat Chinese buffet.

• Rely on hot mustard sauce or hot chile sauce to add zing to your meal with minimal additional sodium, sugar, and fat.

• If you eat family style, order fewer dishes than the number of people at the table. This controls portions from the start. And make at least one of the dishes you order vegetables only.

• Use chopsticks. They will slow down your eating, particularly if you haven’t mastered using them yet.

![]() Get It Your Way

Get It Your Way

• Ask to have extra vegetables added to a dish to make it more healthful and filling. You might have to pay a bit more.

• Dishes are made to order in sit-down Chinese restaurants, so feel free to ask that one item be left out or others be added in.

• You may want to order a sauce on the side and use the dipping technique to limit the amount of sauce you eat. This may help decrease both your sodium and sugar intake. However, make sure that you don’t sacrifice flavor and taste so much that you’ll feel deprived.

• Request that no MSG or cornstarch be used in your dish, to limit sodium and carbohydrate, respectively.

• Ask what type of oil is used for stir-frying. If lard or another type of saturated fat is used, request that peanut oil or some type of vegetable oil be used instead.

• Request that the protein source in your dish be sautéed rather than breaded and deep-fried.

![]() Tips and Tactics for Gluten-Free Eating

Tips and Tactics for Gluten-Free Eating

• Most soy sauce is made from wheat, which means that gluten-free diners should avoid it, and it is included in many typical sauces served in Chinese restaurants. Ask about thickeners, marinades, and seasoning ingredients, as they typically will contain soy sauce.

• Noodles, crispy chow mein noodles, lo mein, egg roll and wonton wrappers, and other deep-fried foods typically contain wheat unless otherwise noted. Fortune cookies are made from wheat.

• Try plain steamed or stir-fried meats, poultry, fish, or seafood dishes with vegetables that are prepared without soy sauce in a clean wok.

• Order plain rice or rice noodles (make sure they are labeled gluten-free) or brown rice if they have it. Bring your own gluten-free soy sauce to the restaurant.

• Ingredients such as rice wine, rice vinegar (wheat may be added to some Asian black rice vinegars), dried mushrooms, cornstarch, garlic, ginger root, spring onions, oyster sauce (if it contains soy, it’s most likely not gluten-free), rice, sesame oil, chile paste, and tofu (plain is gluten-free, but fried may not be) are gluten-free.

![]() Tips and Tactics to Help Kids Eat Healthy

Tips and Tactics to Help Kids Eat Healthy

• Avoid ordering off the kids’ menu if there is one. The kids’ menu often has items that are high in fat, such as fried rice or deep-fried honey chicken. Instead, go family style and share one or two dishes that have been steamed or lightly stir-fried in a wok, rather than deep-fried. Remember, you’re having a healthier meal and serving up lifelong healthier restaurant eating skills at the same time.

• Order brown rice rather than white rice. If your child is new to brown rice, consider ordering a side of white rice and a side of brown rice. Combine them to gradually introduce your child to the taste of brown rice.

• Rather than fried rice, consider a side of steamed vegetables, which you can dice at the table and add to steamed rice if you’d like.

![]() What’s Your Solution?

What’s Your Solution?

You and your friends decide to visit Chinatown to celebrate a friend’s recent promotion at work. Your friend chooses a traditional Chinese restaurant, which has a menu that is written in both in English and Chinese. Yet, language is still a barrier between you and your server.

What can you do to ensure the healthfulness of your meal, determine your insulin dose, and maintain your blood glucose control, even though the language barrier will make it difficult for you to inquire about the details of dishes or make substitutions?

a) Request hot and sour soup as your appetizer if your friends are splitting high-fat appetizers.

b) If the group is ordering family style, be the one to suggest at least one vegetarian selection.

c) Convince your friends to order family style, then use your eyes and taste buds to help guide you on which dishes will fit within your strategy.

d) Ask your server to bring a few takeout containers along with your entrées.

See the end of the chapter for answers.

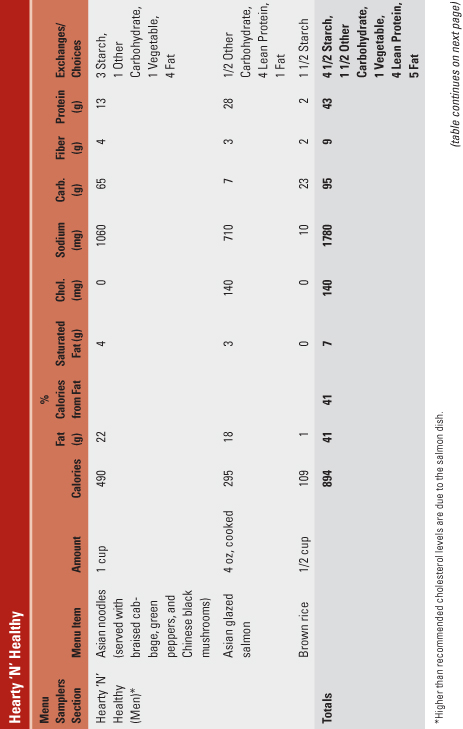

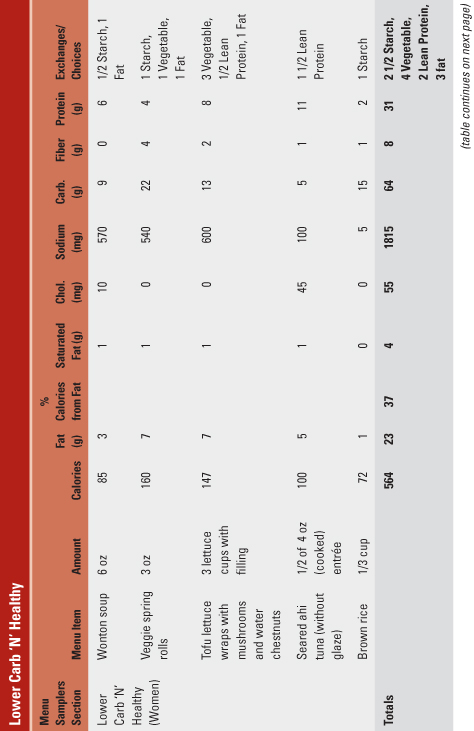

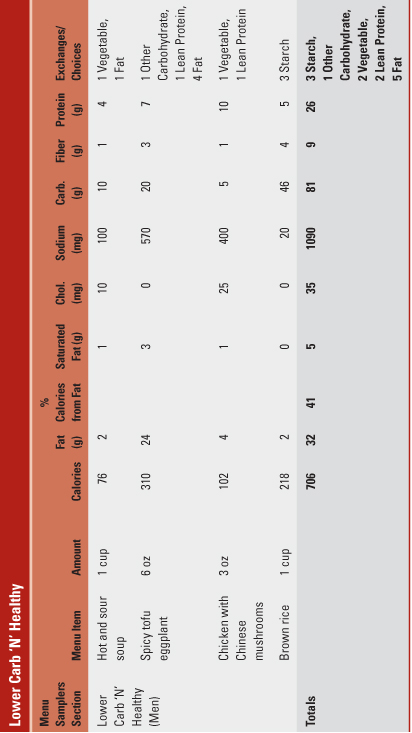

![]() Menu Samplers

Menu Samplers

Menu Lingo

• Bean curd: is made from soybeans and formed into cubes. It is known as “tofu" to Americans. You’ll see it used in soups and other dishes. Be careful to request that it not be fried because it is often fried in entrées.

• Black bean sauce: a thick, brown sauce made of fermented soybeans, salt, and wheat flour. It is frequently used in Cantonese cooking.

• Bok choy: looks like a cross between celery and cabbage. It is also known as Chinese chard.

• Five-spice powder: a reddish-brown powder that combines star anise, fennel, cinnamon, cloves, and Szechuan pepper. It is often used in Szechuan dishes.

• Hoisin sauce: a thick, sweet-and-spicy sauce, also called plum sauce, made from soybeans, sugar, garlic, chilies, and vinegar. Served with moo shu dishes.

• Lily buds: dried, golden-colored buds with a light, flowery flavor. They are also called lotus buds and tiger lily buds and are often used in entrées and soups.

• Lychees, or lychee nuts: a crimson-colored fruit with translucent flesh around a brown seed. They closely resemble white grapes.

• Monosodium glutamate (MSG): a white powder used in small amounts to bring out and enhance the flavors of ingredients. (Note: MSG doesn’t contain gluten.) It contains sodium, but not as much as salt.

• Napa cabbage: also referred to as Chinese cabbage, it has thick-ribbed stalks and crinkled leaves.

• Oyster sauce: a rich, thick sauce made of oysters, their cooking liquid, and soy sauce (which may contain gluten). It is frequently used in Cantonese dishes.

• Plum sauce: an amber-colored, thick sauce made from plums, apricots, hot peppers, vinegar, and sugar; it has a spicy sweet-and-sour flavor.

• Sesame oil: oil extracted from sesame seeds. It has a strong sesame flavor and is used as seasoning for soups, seafood, and other dishes.

• Soy sauce: either light or dark, is used in lieu of salt in virtually all Chinese dishes.

• Sweet-and-sour sauce: a thick sauce made from sugar, vinegar, and soy sauce (which may contain gluten). Meat, chicken, or shrimp served in this sauce usually have been dipped in batter and fried.

• Wood ear: a variety of tree lichen, which is brown and resembles a wrinkled ear; it is soaked before use. Found in soups and some vegetable dishes.

![]() What’s Your Solution? Answers

What’s Your Solution? Answers

a) Ordering soup at a Chinese restaurant is always a smart choice. The soups are generally low in calories and can help take the edge off your appetite.

b) Requesting a vegetarian entrée, or even a vegetable-based side dish, can help balance out all the sources of protein in the dishes on the table.

c) Sharing dishes family style is one of the best strategies you can take. Not only will this help with portion control, but, given the language barrier, it will give you the opportunity to gauge the healthfulness of the dishes based on appearance and a small taste. Then you can decide what you want to put on your plate.

d) Smart move! It’s easy to overeat when there is a lot of food on the table, especially when you’re enjoying leisurely conversation with friends. Boxing up some of the food from the start will help keep you (and your friends) from overeating.