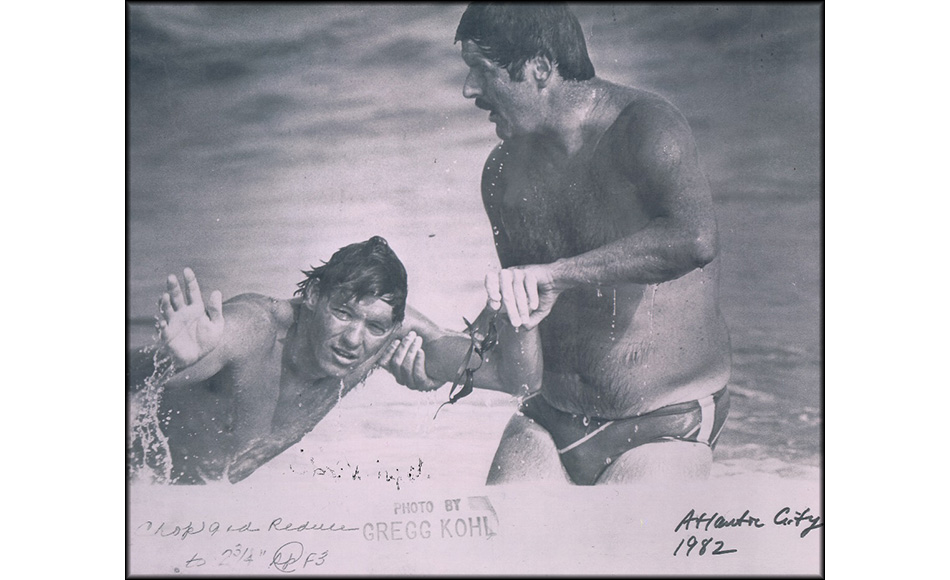

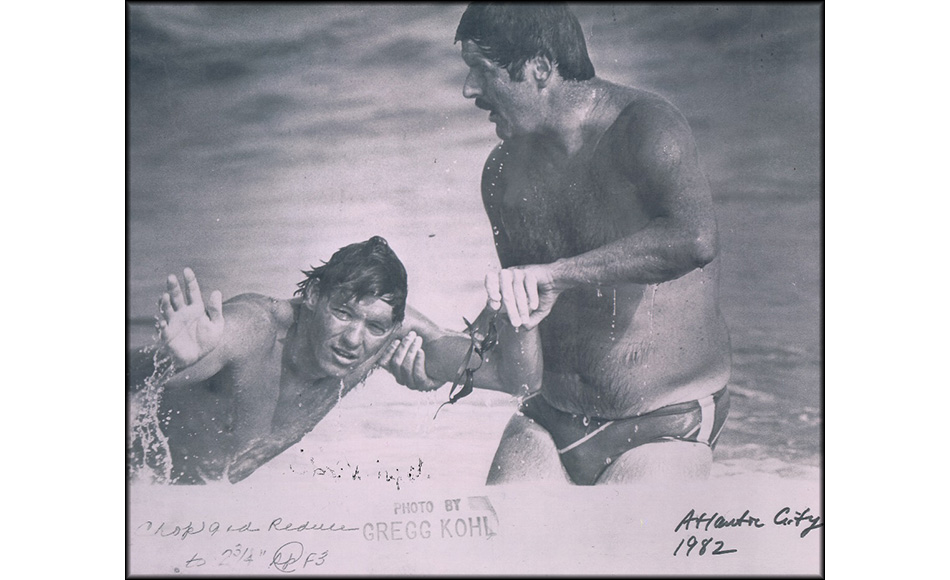

Sam Freas: my coach, lifeguard, and inspiration at the finish of the brutal 1982 race

Photo credit: The Press of Atlantic City and Gregg Kohl

“Or let us also boast in our sufferings, knowing that suffering produces endurance, and endurance produces character, and character produces hope, and hope does not disappoint us, because God’s love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit that has been given to us”

ROMANS 5:3–5, NEW REVISED STANDARD VERSION.

Being able to swim marathon races after ten years in the sport, and to be able to continue to pursue my passions after so many years, was such a great blessing in my life, and also a nice surprise. Most swimmers my age had all stopped competing after the 1980 Olympic boycott, or the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games. Still swimming extremely well in my eleventh summer after college graduation was a wonderful gift that I didn’t take for granted. My summer “job” wasn’t a job at all for me; to put away my business suit and tie and don a swimsuit, cap, and goggles for races around the world, and see old friends and make new ones, was an annual highlight of life.

After receiving prize money in my first professional marathon swimming race in 1980, the rules of USA swimming and the United States Olympic Committee prohibited me from competing as an amateur athlete. After the 1988 Olympics, this rule changed and there was no longer a distinction between amateurs and professionals in swimming and most other Olympic sports.

The 1991 FINA World Aquatics Championships were going to be held in Perth, Australia, and for the first time there was going to be an open water swimming event, a 25-kilometer race. I was excited to be able to try to represent USA Swimming again. Since 1980, I had represented the USA around the world but always as “Paul Asmuth,” an individual and not part of an “official” USA team.

The professional marathon swimming races had been my focus for the past ten summers. This season all of my training was geared toward the 25-kilometer (15½ miles) United States Swimming Open Water National Championships and the Open Water World Championship Swimming Trials in Seal Beach, California, which was held on July 21, 1990. The top two men and women in the race would travel to Perth and compete against the best open water swimmers in the world, and I wanted to be one of them.

Most of the marathon swimming races that I had competed in over the last ten years were more than 20 miles, and as this swim was shorter, I was still confident in my abilities. Although at this point in my marathon swimming career and almost thirty-three years old, I was no longer considered a medal contender, and knew that I would need to train very well to reach my goal.

In the spring I was contacted by a young reporter I knew, Ken McAlpine, who had written a couple of feature stories about me for different publications. He had pitched my story of trying to make the world championship team to Sports Illustrated and was hired for the job. Ken and I spent a lot of time together talking over the next couple of months, and he was always a pleasure to visit with. It was exciting to think that my story could end up in SI.

To help prepare for the summer of racing, I traveled to the Olympic Training Center (OTC) in Colorado Springs, Colorado, and joined Coach Mark Schubert who was the head coach of the University of Texas at Austin women’s swimming team. Mark and I had known each other since 1976, when I first moved to California to train with the Mission Viejo Nadadores, and I looked forward to training with one of the world’s best distance coaches again.

The OTC opened in 1979 and is a converted Air Force base. At this time the dorms were just like sleeping in barracks. Bunk beds, bathrooms down the hall, and definitely not luxury. Thankfully, the cafeteria meals were excellent and geared toward offering a lot of healthy foods to athletes who needed thousands of daily calories. The United States Olympic Committee picked Colorado Springs as an Olympic training venue partially due to the benefits of training at altitude. The training center is at an altitude of approximately 6,000 feet.

Altitude training primarily helps athletes who are competing in mid to longer distance events that are more aerobic versus anaerobic in nature. Anaerobic athletic events are short sprints or have immediate exertion, like weight lifting or throwing the shot put. These quick bursts of energy require more oxygen to the muscles than the amount of oxygen that is available within the body’s cardiovascular system, creating oxygen deficiency.

Aerobic exercise requires energy over a sustained period of time and the body uses glycogen stored in the liver and muscles along with fats as fuel. Physical exertion over 3 to 4 minutes in time are aerobic activities that use the body’s stored energy as well as cardiovascular circulation to transmit oxygen and other nutrients to allow the muscle fibers to keep firing. Oxygen is transmitted to the muscles via red blood cells. Because of the lower oxygen levels at high altitude, the human body acclimates over time and produces more red blood cells to accommodate for normal oxygen levels in our system. When an athlete returns to sea level for a competition, the increased number of red blood cells carry more oxygen during the event, which can increase performance. This is why Mark’s team and many other Olympic-caliber athletes come to the OTC for training camps.

Until your body has time to acclimate, training at altitude is much harder than sea level, and the adjustment takes some time. Typically, training camps last two to three weeks for the athlete to receive the full physiological benefits of high-altitude training. I would be there for eighteen days of training, and the first week was really rough.

At this time, there was no pool at the OTC and we traveled by bus to either a nearby outdoor 50-meter pool or to the United States Air Force Academy (USAFA) just north of Colorado Springs. The USAFA is located on a beautiful campus of 18,500 acres on the east side of the Rocky Mountains. Training at 6,000 feet in Colorado Springs was hard enough, and at the USAFA we looked at a huge sign on the pool wall that we could read when turning our head to breathe: “The air is rare at 7,258 feet.” Yes, it is. Training 1,200 feet higher than Colorado Springs was very challenging, and I “gasped” my way through the first week of workouts.

Our ten workouts a week were typically 7,000 to 9,000 meters, and we swam over 70,000 meters each week. Very tough training, and recovery at my age was not as quick as when I was twenty-three; I was sore, tired, and probably a little cranky, too. By the end of training camp I had dramatically improved my conditioning, and knew that I was getting close to being ready for the challenging marathon swimming season. I will always be grateful to Mark for allowing me to train with his team, and the Texas women swimmers, for making room for me in the pool lane and treating me like a teammate.

The day after arriving home I swam in a 2-mile open water race in Lake Berryessa, California. I will never forget the endurance and speed I had during the race from the benefits of altitude training, which made me feel like I couldn’t swim fast enough to get out of breath. Almost like a flying fish skimming over the tops of the waves. Wow, I wished that I could feel this way all of the time.

Two weeks later I was in Italy for the 20-mile Capri to Naples marathon race. I knew that I would swim well. The prior year I contracted a stomach flu the night before the race, was sick throughout the swim, and finished a disappointing seventh place. Having won the race three previous times, I was very disappointed and anxious to get back to winning again, if possible.

The first few hours after the start went really well. I felt great swimming in the front, then in the second half of the race I ran out of energy and finished third, which was disheartening given the shape I was in from my training. I felt that I may not have rested enough, and could just have been a bit tired from intercontinental travel. With marathon swims being so long, being physically off just a little bit can add up to a lot of time over the day; 30 seconds slower per mile is a 10-minute loss over 20 miles. Time to go home for the final push before the world championship trials.

Back in California I really felt powerful during my Mission Viejo pool training, and Corona Del Mar ocean swims, and knew that I was ready for a good race. I met with a young man, assigned to me by the race organizers, who would guide me during the race from his kayak. We had never met before, but I was impressed with his local knowledge of the Seal Beach waters and his kayak experience. We practiced once together before the race and found a nice rhythm for our feeding schedule.

The race started out well and I was able to take the lead, along with Chad Hundeby, from Irvine, California, a Southern Methodist University NCAA All-American distance swimmer and renowned distance pool trainer who had won previous USA Swimming long distance national championships. I felt really good and we set a fairly fast pace. Water temperature was in the low 70s and sea conditions were typical, with some choppy waves; nothing unusual for me.

After about 2 hours of swimming I began to feel fatigued, similar to how I had felt in Italy, and couldn’t hold the pace any longer. As I slowed over the next 3 hours, Chad pulled away from me, and then another swimmer, Jay Wilkerson from Florida State University, passed me. It was a very disappointing day, finishing third in 5 hours and 18 minutes. What a letdown, knowing that my preparations had gone so well, and not being able to understand why my body was not responding like other years. Am I getting too old for this? I thought.

After more than 50 marathon swims, I had never felt this way during competitions. There would be no trip to the world championships, and no Sports Illustrated article for me. I flew to Quebec City three days later for the 32-kilometer La Traversee du Lac St. Jean the next weekend. I was exhausted and now had no idea what to expect in the cold waters of Lac St. Jean.

When racing week to week in marathon swimming, there is very little to do between swims except recover from the previous race. Increasing training to a level that causes additional muscle fatigue, or slows recovery from the previous race, is a mistake. I knew to train very little and rest. Each day I swam for about 30 minutes in preparation for the race on Sunday.

Lac St. Jean is always one of the toughest marathon swimming races due to the distance, cold temperatures, and rough waters. The crossing had been changed from the prior year’s 64-kilometer (40 miles) double lake crossing to an extended one-way crossing of 40 kilometers (25 miles). Historically the distance has been 32 kilometers (21 miles), with the exception of the double crossing years.

The entire race was a slog for me and I never felt good, like swimming through the mud. I felt very flat and tired, finishing in 10 hours and 1 minute, a distant fifth place—over 40 minutes behind the winner Diego Degano, a new and very talented young stud from Argentina. Finishing fifth was tough enough, but finishing behind athletes I normally beat was humbling and frustrating.

After returning home, my three-year-old daughter Kendall helped put life back into perspective with her hugs and kisses, and letting me know that “It’s okay, Daddy, letting the other boys win sometimes is nice.”

Knowing something wasn’t quite right with my body, I decided to see the doctor for blood work, hoping to find answers for why I was feeling so fatigued, and swimming poorly for the last few weeks after great training the months before. I had the final race of the summer in Atlantic City, and after seeing my blood-work results, the doctor told me not to go. He said that I was recovering from a viral infection and needed rest. At least I now knew that my physical fatigue was not psychologically related, and helped to explain my poor performances.

There really wasn’t anything for me to do but maintain my fitness level, and see if I began to feel any better before Atlantic City, only three weeks after Lac St. Jean. I dropped my training down to about 30,000 meters each week, with only two longer swims in Lake Ilsanjo, a week apart.

I decided to swim in the last race and see how it would go. After arriving in Atlantic City, I met with my coach, Carl Smallwood, who had been in my boat the previous four years, to say that it had been a tough summer. I shared with Carl that I was in great shape, but that there had been a setback, and that I was there to swim the best I could.

After arriving on Wednesday for the Sunday race I was still fatigued and needed rest. Each day I would swim with Carl at the Margate Beach for 15 to 30 minutes, enough to loosen up, and then rest all day on the couch, watching movies. Carl and his wife Gerri took great care of me during the week, making sure that I got as much rest as I could. Not having won the race in 1988 or 1989, there was little prerace pressure from the media and I could relax. No one expected I would do much after my summer’s results so far. I wasn’t sure, either.

Based on when high and low tides were going to be on race day, we knew that the currents going out at the race start, coming back into the back bay in Longport, and finishing the race were going to be very difficult for all of the swimmers and rowers. The conditions were shaping up to possibly be the toughest ever. Exactly what I didn’t need this year.

Carl and I spent time scouting out the critical inlet locations in Atlantic City and Longport before the race so we would know exactly where I would swim in each location against the currents; this knowledge would be critical. Making a small mistake while swimming against water moving at 2 miles per hour or more in the opposite direction can quickly balloon into a problem that changes the outcome of a race. Not to mention push me into something that could hurt my body. Over the years, I had learned not to take chances when swimming against current.

The race was full of great swimmers, including the prior year’s winner David Alleva (a University of Virginia NCAA All-American), Rob Schmidt (a University of California at Berkeley NCAA All-American and a relatively newcomer to the racing circuit), and Diego Degano from Argentina. All of them had won big-time races in the past and were about ten years younger than me. Rob spent the summer working for the Atlantic City Beach Patrol and had the most time to prepare for the battle in race-like conditions. James Kegley was also in the competiton; he had started racing the same year as me, a wily veteran, and always a threat.

On race morning, Carl’s son, Carl Jr., a Margate Beach Patrol lifeguard, was helping to row the lifeguard dory today, along with Wayne Coleman, a Ventnor City lifeguard who went on to play in the NFL. These young bucks with chiseled and tanned muscles were experienced oarsmen, just what we would need today. Coach Carl, who was the captain of the Margate Beach Patrol, was also good on the oars. Today was going to be a grueling marathon row as well, and a great team in the boat can make a huge difference.

The World Championship Ocean Marathon Swim as the race was now known (I always liked the original “Around the Island Swim” name) started in the back bay at Harrah’s Marina Hotel Casino, across from Historic Gardner’s Basin, where the start was for many years. Today it was interesting for me. I was more nervous about not knowing how I was going to feel during the race, versus nervousness about the competition. Especially knowing that the currents were going to make for a very long and punishing day. I felt no pressure from the competitors or the media; no one expected me to challenge this new, young generation of athletes.

It was so interesting to compare the competitors at this year’s start to those in my first race in Atlantic City a decade earlier. Today the athletes were strong, trim, and fast. Ten years ago there was a combination of body types; even Claudio Plit, who was three years older than me and still racing, had lost 20 pounds and dramatically improved his speed. This year, everyone had shaved down their body for maximum performance; in 1980, I was the only one. The athletes had rapidly evolved for the sport in a short span of time.

When the starter’s pistol went off there were twenty-three primed competitors trying to swim around Absecon Island in 9 hours or more, and we all took off in a rush to get behind our lifeguard dories to draft. We all knew that the sooner we could get to our boats and start drafting, the faster we would go, and the straighter we would swim following our craft.

As we exited the marina and turned right toward the ocean, the currents were already pushing against us as we headed out to sea. The ocean water was cool, in the low 70s, and swells pitched the small boats and made staying behind them to draft much harder. I always love the scene of the tightly bunched boats, oars rhythmically moving, flags of each swimmer’s country waving, and swimmers splashing water into the air as we headed out to sea. Never knowing when would be my last year racing, I took in the beauty of the moment and prayed. Thank you, Lord, for giving me another season. Certainly not what I had hoped for, but I was forever grateful to be able to embrace my passion for swimming.

Rob Schmidt took out the first part of the race very fast, and as we approached the open ocean the current was so strong we had to leave our boats and swim right next to the rock jetty. Waves pushed us into theboulders, and barnacles growing on the craggy rocks scratched and cut our skin. We were only 30 minutes into the race and already getting beat up by the sea; she would be cruel to us today.

Making slow headway as we worked our way against the current reminded me of the first race my mom came to see in 1982. She never liked the sport but wanted to show her support; she flew up from Florida to watch her first marathon swim. It was the beginning of my third season. To create a more dramatic start and finish, the race organizers decided that the race would start on the beach and the athletes would have to run and swim through the surf, swim around the island, navigate our way back through the breaking waves, and finish on the beach. What a disaster.

The currents punished us at the end of the race as we tried to make our way back out into the ocean; we were actually swimming in place at times. My mom had followed me all day, from the start, to the Longport Jetty, to each bridge we swam under, and now, after almost 9 hours, was on the rock jetty we had to get around to finish. Everyone was struggling and getting beat up against the rocks by the waves and current. As I breathed to the right I saw my mom standing on the jetty, cheering, “Go, Paul. Go, Paul.” And I kept swimming. Then after many more minutes of effort I would look to the right and there was my mom, standing on the same rock, cheering; “Go, Paul. Go, Paul.” It was like a terrible déjà vu experience, only real. I wasn’t moving. “Go, Paul. Go, Paul,” she would cheer standing in place. How wonderful to have her support, and what a nightmare to be experiencing the torture of the moment. She had to be shocked and scared for me; I know I was. It was one of the hardest races I had ever completed, and my coach at that year’s race, Sam Freas, had to help carry me out of the water.

Sam Freas: my coach, lifeguard, and inspiration at the finish of the brutal 1982 race

Photo credit: The Press of Atlantic City and Gregg Kohl

At the end of the Atlantic City rock jetty we all took a right turn and headed south toward Longport. There were now many casinos to look at along the Atlantic City Boardwalk, rising high and modern. Much had changed in this city, and it was very different than the old family-oriented boardwalk, or even from my first year here in 1980, when there were only three casinos. The large buildings seemed like forever to reach, and slow to pass, as we swam by at about three miles per hour.

Rob continued to push the pace and I let him go, wanting to conserve my energy and still not knowing how I was going to hold up later in the day. The Ventnor Pier is a little more than the halfway point of the 7-mile ocean leg of the swim, and Rob was 3 minutes ahead by this point. I was feeling pretty good and just kept relaxing into my stroke, focusing on the keel of the boat and drafting as efficiently as I could. A three-minute lead at this pace was more than 200 meters, and I knew that this was significant.

Carl was giving me updates on the dry erase board, and we were working well together again. Just after Ventnor, Carl informed me that we were slowly closing the gap on Schmidt—175 meters, then 150 meters. I kept my same pace, encouraged that the gap was shrinking. I also knew that distances can be deceiving when swimming in current. Rob may have been slowed by currents we had yet to encounter as we approached the Longport inlet, where the tide was already ebbing and the swiftly moving water was ripping out to sea.

Drafting behind lifeguard dory

Photo credit: The Press of Atlantic City

Maintaining my same pace, the gap continued to close, and now I was only 50 meters behind as we swam closer and closer to Longport. The Longport rock jetty was packed with fans waving American flags and cheering us on. As we approached the shore Rob’s boat stayed a little farther away from the rocks than Carl and I had planned. Rounding the jetty, I was now only 10 meters back and gaining quickly as Rob’s boat was farther out in stronger currents.

Just like we had envisioned and practiced, I turned in toward the inlet beach, swimming in water less than two feet deep. My hands were pulling through the sand as the waves were breaking around me. The water was too shallow for the boat. Carl and crew stayed out of the surf zone in deeper water, straining with all of their strength to move against the current. Schmidt’s crew may have thought I was still with my boat, as they stayed out in the much stronger current, and by the time I turned into the back bay, I was now in the lead by 45 seconds.

Rounding the final rock jetty into the back bay, it felt like I was fighting against a water cannon (had someone left a fire hydrant open?). I knew that the time to swim faster was now, as Rob struggled with the same obstacle I had just come through and hopefully I could put some distance on him. With Carl banging the boat transom—“bam, bam, bam, bam!”—encouraging me to push the pace NOW, I concentrated on drafting and swimming as fast as I could. Stroke, stroke, breathe, stroke, stroke, breathe… Rob gathered himself after Longport and came charging after me, swimming very well.

I pushed the pace through the back bay communities of Longport, Margate, Ventnor, and Atlantic City, and my lead slowly grew. After swimming for almost 7 hours, my arms, legs, and back ached with pain, but I was happy to have my normal swimming energy back, unlike the prior three races (I guess being a couch potato for a week can be good sometimes). As we weaved our way through the small canal, I was encouraged to keep going by the thousands of fans on the jetties, bridges, and in backyards.

The back bay waters were warm and calm, and by focusing and pushing as hard as I could by the time we reached the Albany Avenue Bridge with about 6 miles to go, our lead over Schmidt had grown to 4 minutes. Under normal conditions we would swim this distance in about 2 hours, but today we knew the hardest part of the course was still before us. No lead was safe in these conditions.

By the time we reached the Absecon Boulevard Bridge, the tide had turned and was now flooding into the back bay with a new force. I hugged the grassy shoreline and swam in water as shallow as possible, with my hands raking through the mucky bottom. The heat from decomposing mud was radiating into the water and the sulphur smell of rotting grass filled my lungs. Hard to get into the zone in this hot and smelly soup; not so nice around here.

We pushed on. To try to stay out of the cruel currents, I swam alone next to the shore. The water is too shallow for the boat. Rob is still just behind us and mimicking our tactics.

In the middle of nowhere, along the grassy shore, miles from any homes, there suddenly stood two steadfast fans who were always in this same spot, year after year, and I quickly waved to thank them (no time to dillydally). They had a sign that they waved back and forth: “Go, Paul Asmuth.” I will always remember and appreciate the long walk they took to cheer me on in this remote area, with horseflies buzzing everywhere. A very special sacrifice for me, and great encouragement.

Paul, Logan, and very special fans who stood at the same spot in each one of my Atlantic City races, their encouraging cheers and signs helped me more than they will ever know. Bless you!

As we approach Harrah’s Resort, there are piers and docked boats that extend out into the water. I’m barely moving forward, and upon reaching the docks, I realize that the water is rushing so fast that I cannot make it through. I yell to Carl, “I can’t swim against the current. I will have to pull myself around.” Carl quickly gets permission from the race director, Jack Garrity, and I begin pulling myself around the first dock, hand over hand, from pier to pier.

Suddenly my lead over Rob is less than 2 minutes, as his boat is able to watch what I was doing and not waste time figuring out the solutions. There was a 60-foot-long catamaran along the outside dock and we decided I would need to swim underneath the boat by myself, between the two big hulls, which was frightening. I slowly inched my way forward underneath the large craft, fighting against the rushing water, with nothing to hold on to if needed.

Just before the Brigantine Boulevard Bridge, there was a final dock filled with boats that I needed to make my way around, and the only way I could move forward was hand over hand along the dock or boat transoms. Now I was scared. This was no longer just about swimming, this was surviving. One slip and I might be sucked under the dock or boat. Rob was only 50 meters back and way too close.

As I tried to swim around the final dock the water pushed me under and toward a piling. I braced myself against the slimy and barnacled post, and pushed off to try to move forward. Carl yelled, “Don’t do that or you will be disqualified!”

I yelled back, “I either push off or drown!”

Carl replied, “Okay, I guess pushing off is the thing to do.”

I kept going.

I used every ounce of energy that I had left, and was able to get free from the last dock and swim behind the boat again. We all strained against the torrent of water trying to push us backwards to get under the bridge, and swim the final 500 meters into the marina finish line. The current was relentless, and I continued to strain along with my rowing crew. Swimming in these conditions took us an hour to go only 1 mile. I was bruised and beaten from the rocks and barnacles that had scraped me during the race.

Stroke by stroke and foot by foot, we slowly crawled our way away from the bridge and into the marina, finishing in 9 hours and 54 minutes. Happy tears of gratefulness filled my goggles as I reached up to shake Carl’s hand, and thank Carl Jr. and Wayne for the amazing job that they did.

Coach Carl Smallwood and Paul after 9 hours and 54 minutes of marathon swim racing

Photo credit: The Press of Atlantic City

Other than swimming the 40 miles of Lac St. Jean, it was the hardest swim of my life and the slowest winning time since 1964, more than 2 hours slower than my first win in 1980. Rob finished 2 minutes later, Degano 22 minutes after him, and Kegley another 9 minutes back. The prior year’s winner, David Alleeva, was fifth in 10 hours, 42 minutes. The conditions were so tough this day that only six swimmers finished the race.

Carl, Carl Jr., and Wayne were as exhausted as I was, and we all knew that today was special. Very special for me after such a tough summer of swimming, and extraordinary for them to be part of an amazing marathon, in the water and boat. This was my eighth and final victory in Atlantic City. Maybe the challenging currents this year were fitting. The water rushing past can be so much like our lives. After eleven seasons in the sport, time was rushing by for me, just like the water.

Watching the video of the live television coverage later was fascinating for me. To see the challenges that we had endured, and the end result, made the journey of the summer even more of a blessing. The summer didn’t go the way I had hoped, and yet God had brought me through the storms and blessed me with another season of competitions, travel, and friendships. I was a grateful young man.