Introduction

Shuttles in the rocking loom of history,

the dark ships move, the dark ships move,

their bright ironical names

like jests of kindness on a murderer’s mouth;

plough through thrashing glister toward

fata morgana’s lucent melting shore,

weave toward New World littorals that are

mirage and myth and actual shore.

Voyage through death,

Voyage whose chartings are unlove.

—Robert Hayden, “Middle Passage”

Toward a new humanism. . . .

Understanding among men. . . .

Our colored brothers. . . .

Mankind, I believe in you. . . .

—Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks

I might as well begin with the truth. In 1971, bundled onto a bus, my satchel stuffed with pencils, paper, and the flushed hopes of neighbors and kin, I traveled beside my sister to one of the newly desegregated schools of North Carolina’s Mecklenburg County. Shielded by childhood oblivion from the polite vulgarity and polished hostility that greeted us as we left the nondescript, working-class black enclave of Beatties Ford Park to etch our ever so light traces onto the history of a reluctant America, we entered into the drama of desegregation buffeted by hopes that the promise of liberal humanism that rang so triumphantly in American public discourse might indeed come soon, and very soon, to apply to all the country’s citizens. In the 1970 Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education ruling, the Supreme Court offered a tentative, and explicitly temporary, response to the cynicism that surrounded the interpretation and (non)enforcement of the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision. The fact that in all its foundations and practices the United States is a profoundly segregated society had become so apparent as to make it clear that no institution in the nation is immune to the charge of either white supremacy or mediocrity. Thus, the breathless self-congratulation of liberal America notwithstanding, the United States effectively remained as racially segregated in 1970 as it had been in 1954. Until the Swann decision, Mecklenburg County’s residential patterns proved more than enough to maintain the system of dual education (whites in county schools; blacks in city schools) that had existed since the founding of the Charlotte city schools system in the latter part of the nineteenth century. The decision was crafted to address this frankly vulgar reality by mandating a complex system of busing to achieve racial integration, sending tens of thousands of students rushing each morning to local stops where they boarded garishly yellow metal tubes of hope and modernity, striving in their uncomfortable, stiff-backed seats to achieve what their forebears could not.

In the process, Charlotte gained notoriety as one of the most advanced locations in the New South, the “city that made desegregation work.” Riding those buses, coveting hoarded resources, we crisscrossed routes marking the resilience of a striving black working class struggling against the no-nonsense will to maintain white privilege and distinction: Beatties Ford Park to Long Creek; Hidden Valley to Newell to Northeast to Albemarle Road; Hampshire Hills to Garinger. Becoming accustomed to watching friendly, good-natured, and ostensibly liberal white people turn and run at the approach of black children overburdened with slide rules and history books, we learned early and well not only how little truth lay behind the oft-repeated rhetorics of fairness and color blindness, but also that the modes of our education had been developed precisely to squelch awareness of the forms of violent repression being directed squarely in our direction. Entering in 1983 as a scholarship student into the University of North Carolina and eventually making my way to New Haven for postgraduate studies, I was reminded each step of the way of my luck and exceptionality, told to be proud and rejoice as I left graduate school in 1994, energized and expectant, if more than a bit apprehensive, with a newly minted Ph.D. shining warmly in my pocket.

The uncomfortable truth, however, the inconvenient reality that fuels the sense of irritation stretching through these pages, is that the story that I have just narrated is not the typically American tale of triumph over adversity, but instead a much less elegant, infinitely more pessimistic account of cynicism, hypocrisy, and disappointment. During the years of my university education, Charlotte’s economy boomed, drawing impressive numbers of individuals from the Northeast and Midwest, who came to what they understood as a prosperous, sun-drenched southern city in which the most vulgar aspects of segregation had long been defeated. Imagining themselves as somehow exempt from any responsibility for the antique certainties of the so-called Old South, they chafed at the busing system that had been put into place by the Swann decision. In 1999, facing a challenge by a white parent whose daughter was denied a position in a magnet school because of her race, Judge Robert D. Potter of the U.S. District Court for the Western District of North Carolina ended mandatory court-ordered busing. The predictably disastrous results came almost immediately. Charlotte entered as fully as any American city into the laughing duplicity of post-racial white supremacy. Only six years after Judge Potter’s ruling, Wake County Superior Court Judge Howard Manning accused the Charlotte-Mecklenburg school system of “academic genocide,” pointing to the systematic herding of low-income students into cash-strapped, underperforming schools, citing four city high schools as particularly noxious examples of the city and county’s failing public school students: Waddell, West Charlotte, West Mecklenburg, and Garinger (from which I had graduated in 1983).1

Hearing all this, you will perhaps have some sympathy for why I have so little patience for the reiteration of casual rhetorics of liberal humanism. Though the philosophical foundations of the profession to which I claim an awkward allegiance are built upon notions of logic, clarity, and fairness that presumably will eventually prove the lie of the most vulgar forms of racialism, I have never seen anything even remotely approaching a proper actualization of this ideal. According to the U.S. Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics, as of 2011, 79 percent of full-time instructional staff in U.S. colleges and universities were white, 6 percent were black, 4 percent were Hispanic, 9 percent were Asian/Pacific Islander, and less than 1 percent were American Indian/Alaska Native. Among those individuals holding professorial titles, 84 percent were white, 4 percent were black, 3 percent were Hispanic, 8 percent were Asian/Pacific Islander, and again less than 1 percent were American Indian/Alaska Native.2 Or to state the matter even more harshly, at the current rate of increase, it will take African Americans more than a century for their representation in the professoriate to reach parity with their numbers in the general population.

The idea that allegiance to Enlightenment ideals passed to us from the founders will inevitably result in the realization of a just and race-blind democracy has proven across multiple generations to be either a sloppy fiction or a bold lie. This notion, the almost religious certainty that the ravages of slavery, colonialism, and white supremacy notwithstanding, the basic philosophical, critical, and pedagogical structures that define what we euphemistically name humanism must eventually result in the full articulation of a common good, is itself established on profoundly unstable institutional and ideological conventions that privilege an essentially scholastic intellectualism, one in which it is perfectly acceptable to ignore the hostility to Africans and their descendants that is often quite bluntly stated in the works of Kant, Hume, Jefferson, Hegel, and Heidegger, not to mention their many students and interlocutors. Indeed, it is still the rare scholar who seeks to gauge the quality of humanist debate by direct reference to the lived realities of the communities that sponsor and support his work. Is he smart? Is she thorough? That it is so easy to answer these questions without taking into account the vigor, the genius, and the unremitting struggle of the colonized and the enslaved begs the question of whether progressive intellectuals should continue to sign off on notions of (e)quality and liberalism that effectively rob large swaths of the human population of their resources without bothering even to note the seriousness of the crime.

I will admit, then, that much of what paces and structures this work are equal measures of displeasure and distrust. Attempt to place the words humanism, humanities, human sciences, universalism, cosmopolitanism, liberalism, and black into the same sentence, and you are likely to find that the only concept strong enough to bind them is “failure.” By noting my displeasure, I mean not only to remark my abandonment of forms of intellectualism that avoid questions of utility and historical urgency, but also to name the fact that in the midst of radical structural and demographic change, the philosophical and critical systems that support humanistic inquiry in both the United States and Europe are woefully inadequate. Thus the apparatus of distrust that I name and willfully exploit in these pages is built upon the simple suggestion that “humanism,” the noble study of “Man,” has a quite intelligible history, one based in a set of material realities that are not distinct from the histories of slavery and colonization that set sturdy-limbed southern children boarding buses and chasing hope though pleasant streets bordered by loblolly pines. The blunt question that one must ask is whether the cynical manner in which those hopes have been—and are—systematically blocked and mocked is indeed a proper representation of the reality of humanism and its most significant institutional articulations. Judge Potter’s anti-busing decision was, after all, an affirmation of the “universalist” and “color-blind” ideals that presumably stand at the heart of the Enlightenment traditions that are so staunchly reiterated in dominant pedagogical structures.

It is here that the work I have undertaken diverges from that of a scholar like Cary Wolfe, who along with the feminist scholar of science and technology Donna Haraway has become a central figure in the articulation of what one might think of as the “post-humanist agenda.” In his capacious 2010 study, What Is Posthumanism?, Wolfe rightly points to the fact that in the Western philosophical traditions that he examines, one achieves “the human” by “transcending bonds of materiality and embodiment altogether.”3 The pluralist impulse that is presumably the driving force in liberal humanism is itself dependent upon a pointedly aloof stance to both the material and the corporeal. The ideological apparatuses that structure Western humanism allow us to celebrate uniqueness and diversity without radically altering remarkably resilient structures of exclusion. Speaking of the legal efforts to alleviate the suffering of animals and the marginalization of people with disabilities, Wolfe writes that

these pragmatic pursuits are formed to work within the purview of a liberal humanism in philosophy, politics, and law that is bound by a historically and ideologically specific set of coordinates that, because of that very boundedness, allow one to achieve certain pragmatic gains in the short run, but at the price of a radical foreshortening of a more ambitious and more profound ethical project: a new and more inclusive form of ethical pluralism that is our charge, now to frame. (Wolfe, What Is Posthumanism?, 137)

I am altogether in agreement with Wolfe’s arguments here. I am also equally convinced by his call for thorough—and potentially corrosive—examinations of the material, institutional, and disciplinary forms in which humanism is articulated, as well as his assertion that Disability Studies and Animal Studies have the ability to provide key models for moving the terms of post-humanist debate forward.

What troubles me about Wolfe’s work, however, what provokes that necessary divergence to which I have just alluded, is the fact that not only does he never consider the multiple ways that the intellectual protocols of slavery and colonization have structured increasingly complex and novel manipulations of discourses of human subjectivity, but also that he rushes to dismiss the accomplishments of those intellectual insurgencies that have attempted to do just this work. In defending his turn to Animal Studies, Wolfe remarks offhandedly that

the full force of animal studies—what makes it not just another flavor of “fill in the blank studies” on the model of media studies, film studies, women’s studies, ethnic studies, and so on—is that it fundamentally unsettles and reconfigures the question of the knowing subject and the disciplinary paradigms and procedures that take for granted its form and reproduce it. (xxix)

True to his word, Wolfe then spends the remainder of What Is Posthumanism? making a very convincing argument about the necessity of Animal Studies and to a lesser extent Disability Studies in the articulation of the post-humanist critical project, without ever stopping to demonstrate either concern for or anything more than the lightest and most two-dimensional familiarity with “fill in the blank studies.”

Where I lose contact with the guiding logic of Wolfe’s work is in my inability to understand how in the absence of any consideration of the protocols of race and gender in the articulation of humanism he might achieve the fundamental “unsettling” that he desires. Indeed, he has fallen victim to the very ideological boundedness about which he warns his readers. In his rush to avoid the pitfalls of disciplinary provincialism, he clumsily forgets his own call for a critical practice that deeply considers “the institutional forces it is interested in and the modes and protocols of knowledge by which those materials are disciplined” (106). Wolfe is tone-deaf about the analytical and political labor that has most consistently and doggedly resisted the worst ideological and structural expressions of Western humanism, particularly labor enacted under the rubrics of postcolonial and African Diaspora Studies. Understanding this helps us to make sense of Wolfe’s confusing silence regarding the remarkable achievements of generations of anti–white supremacist, anticolonialist thinkers, chief among them Frantz Fanon, who called for a radical restructuring of humanism nearly sixty years prior to the unveiling of Wolfe’s own essentially closed efforts.

My criticisms of Cary Wolfe are meant to illustrate a particularly sorry reality in the dominant structures of American and European intellectual life. Our complex rhetorics of pluralism take place in contexts—and institutions—that gain much of their social capital by actively repressing truly democratic forms of study and debate. “The black” can be imagined much more simply and comfortably than he can be addressed. This sad truth is one of the factors that fuels the disappointment and distrust about which I spoke earlier. I can easily understand and sympathize, then, with the frustration of a scholar like Frank Wilderson when he argues that the pluralist rhetorics that are the hallmarks of liberal humanism are poor substitutes for much-needed structural change in American and European intellectual life:

In sharp contrast to the late 1960s and early 1970s, we now live in a political, academic, and cinematic milieu which stresses “diversity,” “unity,” “civic participation,” “hybridity,” “access,” and “contribution.” The radical fringe of political discourse amounts to little more than a passionate dream of civic reform and social stability. The distance between protester and police has narrowed considerably.4

The sneering on display here is equal parts shocking, refreshing, provocative, and disappointing. Wilderson is right to call out the cynicism that accompanies so much of the rhetoric that he critiques. The essentially therapeutic modes with which conversations about pluralism and diversity take place in this country operate to forestall deeply needed structural change by assigning an almost metaphysical status to increasingly complex announcements of a never quite attainable beloved community in which the knottiest questions of resources and power are addressed through the deployment of murky rhetorics of mutual recognition and respect.

Strangely, however, Wilderson makes a very significant conceptual error, one remarkably similar to those made by Wolfe. For Wilderson, “the black” is a “paradigmatic impossibility in the Western Hemisphere, indeed the world.” The black is “the very antithesis of a Human subject” (Wilderson, Red, White, and Black, 9). In one manner Wilderson is almost correct. As I will discuss in some detail, the black operates in Western humanism as a nonsubject who gives meaning to the awkward and untenable concept of “Man.” The many articulations in “our” philosophical traditions that read Africans and their descendants as outside history (Hegel) or incapable of the finest procedures of human thought and affect (Jefferson) work to disavow the very possibility of black subjectivity. Moreover, as I have argued repeatedly, the racial liberalism of American and European institutional life, the tepid and slow diversification procedures announced so breathlessly in the grandest of our grand institutions, were never designed to effect anything approaching a broad-ranging reconsideration of the most basic of humanist ideologies and protocols.5

What confuses me about Wilderson’s thinking, however, what makes me wonder whether I have misunderstood his methods and motivations, is his willingness to reiterate—and rely upon—spectacularly rigid conceptions of human subjectivity. For Wilderson, Western humanism is the only game in town. His theoretical models allow no room for contradiction or slippage. He insists upon the most harsh and provocative nomenclature, suggesting that the labels “black” and “African American” should be understood as nothing more than drained examples of sentimentalism and sophistry. The White, the Slave, and the Savage (the Native American) are the only figures with enough conceptual heft to become visible within the philosophical graph that Wilderson produces. I would argue, however, that these essentially political and ethical arguments are marred by Wilderson’s unwillingness to pay attention to the complexity of American sociality, the uncanny messiness of American history. In his rush to produce a radical critique of rhetorics of pluralism, Wilderson has been duped by one of the masters’ most powerful lies. The Western philosophical traditions to which we have all been forced to pay obeisance represent not vessels of truth per se, but instead the quite specific discursive protocols and institutional procedures by which examination and discussion of human being has been delimited.

While scholars like Orlando Patterson and his many students have demonstrated the most salient ideological structures of slave (non)identity, the ways the slave’s natal alienation allows for the transmogrification of a fully socialized human individual into a thing, these ideological structures should never be taken to represent “the slave’s” essence.6 Generations of intellectuals—W. E. B. Du Bois, C. L. R. James, John Blassingame, Deborah Gray White, and many others—have demonstrated not only enslaved persons’ awareness of their presumed status as chattel but also and quite importantly their resistance to this status, their self-conscious articulation of counternarratives of human subjectivity in which enslaved and colonized persons might be understood as both historical actors and proper subjects of philosophy.7 I agree with Wilderson that part of what Black Studies must continue to do is to point out the white supremacist basis of much within the articulation of so-called humanism. Even more importantly, however, I am eager to examine the cultures of enslaved persons, colonized persons, and their descendants in order to begin a process of articulating forms of humanistic inquiry that move beyond the stale compromises and brittle ceremonies that typify so much in the current practice of the humanities and human sciences.

Here is where I stress the pressing need to imagine the beginnings of a post-humanist archival practice. I build upon the work of Wolfe, Wilderson, and the communities of scholars whom I take them to represent, by resisting at every turn the tyrannies of philosophy and sociology. I meet Wolfe’s refusal to engage Black Studies and Wilderson’s refusal of the very idea that “the black” can be studied by arguing that, though the conceits of humanism would have us believe that our ability to address human being must by necessity be a radically demarcated endeavor, the lived reality of black life demonstrates an unusually broad set of procedures that have challenged and critiqued not only white supremacy but also the smugness and certainty of the entire Western humanist apparatus.

In this way, my work is in conversation with that of Alexander Weheliye, who argues in Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human that contemporary discussions surrounding human being, particularly those by Michel Foucault, Giorgio Agamben, Achille Mbembe, and Orlando Patterson, have been too quick to dismiss or ignore “the existence of alternative modes of life alongside the violence, subjection, exploitation, and racialization that define the modern human.”8 He rejects the essentially academic and two-dimensional concepts of human subjectivity that he finds in these men’s work by turning to the self-consciously embodied critiques of black feminist theorists. Focusing on Hortense Spillers’s useful distinction between the body and the flesh, Weheliye claims that flesh, that “zero degree of social conceptualization,” that irreducibly human thing that cannot be properly corralled within the suffocating racialist and woman-hating strictures of Western humanism, might facilitate the excavation of “the social (after) life” of Agamben’s bare life and Patterson’s social death.9 The flesh marks the site at which “lines of flight, freedom dreams, practices of liberation, and possibilities for other worlds” might be made visible (Weheliye, Habeas Viscus, 2).

One runs, however, directly into the question of how. How might we begin to access the tantalizing political/ethical/theoretical possibilities that Weheliye names? My tentative answer is to call not simply for a return to “the archive,” but also for the invigoration of Critical Archive Studies; critical in the sense of operating to end the terror of white supremacy while also naming how the humanist split between Man and (not)man has been achieved and maintained. While I am certainly not hostile to the philosophical and critical methods advanced by Weheliye and Wolfe as they attempt to resist the erasure of the lived, embodied, fleshy reality of humans from the articulation of humanism, I nonetheless believe that the example of the interesting, provocative, but ultimately defeated work of a scholar like Frank Wilderson speaks to the need to look for methods of inquiry, ways of naming human being, that are not bounded by the very forms of philosophy and sociology from which black and female subjectivity are always already excluded. We have no choice but to develop critical methods established at precisely those many moments of illogic, indeed of wildness and bestiality, that one finds in humanist discourse. Or to return to the main rhetorical currents of this book, I will pay particular attention to those many instances where the specificities of “the flesh” are utilized to announce humanism’s dream of transcendence. I will look for not only the many (ancillary, farcical, grotesque) images of black subjects in so-called Western modernity, but also the abundant evidence (at least for the wide-awake reader) of black individuals’ having turned humanist discourse to their own purposes, having utilized the rhetorics of the flesh in order to access alternatives to the most vulgar of the humanist protocols.

* * *

In enacting these procedures, I turn to a remarkably rich, if largely unexamined, archive centered on many decades of intimate interaction between African American and Spanish intellectuals. My fascination with Spain and what I call the African American Spanish archive turns both on the central place of the Iberian Peninsula in the articulation of Western humanism and the impolite, joking, sarcastic, and mocking assumption by many African Americans and other people of color that scores of so-called white individuals (including Spaniards) have not properly established themselves on the right side of the (white) Man/(black) animal binary.

Following the lead of Michel Foucault and Cedric Robinson, I point to the centrality of the Iberian Peninsula in the development of what eventually came to be known as globalization and humanism. For his part, Robinson is particularly eloquent about the ways early modern notions of progress and cosmopolitanism were caught up with the production and reproduction of white and Christian identity.10 I rush to pair these observations with María DeGuzmán’s claims in her remarkable study, Spain’s Long Shadow: The Black Legend, Off-Whiteness, and Anglo-American Empire, that the clear evidence of Iberian cultural forms that predate our contemporary racialist conceits as well as the peninsula’s strategic position at the crossroads of Europe, Africa, and the Middle East have been used by American racialists to call into question the so-called racial purity of Spaniards.11 Swimming against the current, however, I would suggest that the “off-whiteness” that DeGuzmán names signaled for African American intellectuals a species of Spanish promise and possibility, an opening by which the vulgar fiction of white superiority might be mitigated through access to not yet properly defeated Spanish flesh. Thus speaking out of school, I would remind my readers of some naughty truths. Slavery and colonization produced the wealth that allowed for the development of capitalism and spawned the ideological protocols that produced ridiculously clumsy concepts of racial and ethnic difference. At the same time, however, they also produced any number of (un)bounded, (un)authorized counternarratives, in which the many contradictions of racialism and capitalism were made patently visible.

I take inspiration here from work of the Jamaican novelist, critic, and philosopher Sylvia Wynter, who, following Foucault and the anthropologist Jacob Pandian, suggests not only that the Man/human split is a relatively recent invention but also that the conceptual tear that it represents—white, Western, propertied, universal Man versus nonwhite, Eastern, property-less, local female animal—is itself a product of the post-1492 need to put key ideological, discursive, and aesthetic structures at the service of modes of capital accumulation that were at once vigorously acquisitive and none too sentimental about the vicious exploitation of fellow members of the species.12 Thus for Wynter, “the systemic revalorization of Black peoples can be fundamentally effected only by means of the no less systemic revalorization of the human being itself, outside the necessarily devalorizing terms of the biocentric descriptive statement of Man.” It is not enough simply to name yet again the ridiculousness of still quite vibrant discourses of race. Instead we are called to disrupt the basic conceits regarding the proper structures of our most precious modes of intellectual labor. The key work is not so much to deliver “manhood” to “the blacks” as it is to rescue all of us, Africans, Europeans, Americans, and Asians alike, from the stranglehold of a stunningly calcified understanding of human being in which we name and evaluate our aesthetic structures via metrics designed to remark just how far we have traveled along the great chain of being: from hairy beasts with their faces bent to the ground to denatured, no longer quite animal beings fretfully eager to distinguish ourselves from species kin in order to maintain fictions of a disembodied transcendence.

My critique of a critic like Cary Wolfe turns, then, on the fact that even as he rightly notes that humanism is flawed to the extent that it is built upon an indissoluble distinction between “Man” and animal, he nonetheless seems incapable of recognizing that this idea reaches its highest—and most bizarre—level of clarity at those many moments in which some human animals are understood to be more human than others. I want to be clear, however, that the archival work that I propose, the awkward pairing of Spanish and African American intellectualism that makes up the bulk of this study, is intended to help make plain both the functioning and the dis-functioning of these structures, the ways cultures of slavery, white supremacy, and empire work not only to normalize the social and ideological domination of Africans, Asians, and aboriginals, but also to provoke awareness among slaves and slavers alike of shared humanity, common subjectivity, and modern personhood released from the restraints of the local and the native. As Marcus Rediker and Stephanie Smallwood remind us, the enslaved necessarily established new ideologies of belonging and kinship, turning the “neutral” phrase “shipmate” into a mark of endearment and the slur “Igbo” (outsider, stranger) into a label of struggle and aspiration.13

I must remind you, however, that even as we joyously celebrate the victories of our enslaved ancestors, even as we take satisfied stock of how far we have come, we must studiously avoid the triumphalist narratives that are the hallmarks of humanist discourse. I can offer no stories of success and nobility, no salutary tales of the gallant victory of black will over the vulgarities of slavery and the slave trade. Following the lead of Sylvia Wynter, I will not rehash plots that return us to the very Cartesian division of mind and body by which the enslaved and the colonized have been so vigorously insulted. Instead I ask that we consider the idea that the process of extracting the new from the husk of the old was accomplished by both the mind and the flesh. I want to remain alert to the details of how (black human) bodies were not only abused by slavers but also utilized by the enslaved themselves as key sites of resistance and change. Struggling to remain sensitive to the ways the essentially provincial concept of (white, Western, propertied) Man has been established as universal precisely through the willful erasure of the profound violence that attended—and attends—the articulation of humanism, Wynter pushes her readers to understand that the story of Western humanism is not distinct from the story of capitalist/colonialist/white supremacist expansion. In my specific efforts to imagine a modern, future-oriented, and indeed post-humanist Black Studies, I must oppose the continued refutation of the animal in the human/animal binarism. I must attempt to rescue the flesh from the dream’s much-celebrated despotism; must ask what a project of black liberation not built on the “need” to prove that we are indeed men might entail.

Discussing Hegel’s Phenomenology of Mind, Frantz Fanon reminds us that “Man is human only to the extent to which he tries to impose his existence on another man in order to be recognized by him.”14 Amplifying this line of thought, Giorgio Agamben offers a succinctly stated diagnosis of the generative tension between the concept of “Man” and the (human) animal body that supports this concept:

Man exists historically only in this tension: he can be human only to the degree that he transcends and transforms the anthropophorous animal which supports him, and only because, through the action of negation, he is capable of mastering, and eventually, destroying his own animality (it is in this sense that Kojeve can write that “man is a fatal disease of the animal”).15

The strange neologism “anthropophorous” holds one’s attention in this passage. Agamben names the Man-bearing animal, a creature that though proximate to and intimate with Man should never be seen or hailed. To do so would risk revealing the obvious lie of a fundamental distinction between Man and Man bearer. It would disrupt the “action of negation,” the pursuit of mastery and destruction that Agamben suggests as a primary engine of modern society.

While I am convinced by Agamben’s arguments, I also find myself fretting about the targets and the modes of his address. Spectral figure of a profoundly flawed articulation of modernity or not, Man stands as the undisputed subject of these sentences. Man exists. He transcends and transforms; masters and destroys. It seems, in fact, that Man’s never-ending attempts to confront and destroy animality sponsor the flexibility, creativity, and vigor necessary for his ever-proliferating creative projects. In contrast, the anthropophorous animal does only one thing. It supports. Irritatingly, it consistently fails to perform the only other task that has ever been asked of it. It will not die. What Agamben misses here is an opportunity to reimagine this essentially Hegelian narrative of slave and master so as to allow for the possibility of a much more complex and productive relation between Man and anthropophorous animal. Even as he advances a self-consciously progressive philosophical and ethical project, he still cannot imagine a conception of history in which the anthropophorous animal, the slave, the flesh, might be recognized as an actor. Agamben is trapped within the very Man-made rhetorics and ideologies that he is attempting to disrupt. This is why I turn to what one might think of as an extra-philosophical archival project in my efforts to reconsider Black Studies’ relationship to humanism. That is to say, an intellectual tradition built upon the need to support the aspirations of a people thought to be hyper-embodied and bestial is defeated from the outset if it resists only the content and not the form of these slurs.

I beg your forbearance as I turn to a set of images that offer remarkable visual clues to the infinitely productive, always fraught ideological assemblies that draw together Atlantic slavery, white supremacy, capital accumulation, and nativity. The first, José de Ribera’s Maddalena Ventura, con su marido (1631), commonly referred to as La mujer barbuda (The Bearded Woman), is a large (49.6’ x 76.34’) painting of Maddalena Ventura, her husband, and her child, who became public phenomena in the early part of the seventeenth century after Maddalena, aged thirty-seven, began to grow a heavy beard, eventually attracting the attention of the Duque de Alcalá, who commissioned Ribera to paint the Abruzzo-born woman (see figure I.1).

I am wholly taken by both the painting’s confrontational iconicity and its sheer animality. Standing solidly at “dead” center, Maddalena, with her heavy beard, muscled hands, and most especially her ripe (erect?) breast, suggests exactly the masculinist fears of a dominant/dominating femininity that have cut such a decisive path through all discussions of (African) American society and culture. To borrow a phrase from Hortense Spillers, the image of Maddalena reveals a suppressed “law of the mother” that both supports and threatens modern structures of patriarchy (Spillers, “Mama’s Baby”). The point is reiterated by the spectral presence of Maddalena’s husband. Dressed in black, his face emaciated and drawn, his hands nearly hidden, he recedes in the face of his wife’s white-clad, gold-trimmed vibrancy. While Ribera clearly continues both the realism and the sobriety of Caravaggio, he also affects a decidedly forward-looking, inviting, and opulent mood within the painting. I first encountered the work hanging prominently in the Museo Nacional del Prado. It was a crowd favorite, eliciting a sort of bemused, titillated horror among the museum’s visitors. “Bruto!” the Italians complained. “¡Bárbaro!” the Spaniards countered. In either case, one was left with the sense that something fascinatingly ill-disciplined had taken place. I would argue, in fact, that the painting’s prominence in the Prado, smug symbol of Spain’s presumably stable and established traditions, was designed less to celebrate the genius of Ribera than to tame and domesticate La Mujer Barbuda’s radicalism, her hysteria.

Figure I.1. José de Ribera, Maddalena Ventura, con su marido (1631). Hospital de Tavera, Toledo (Spain). Fundación Casa Ducal de Medinaceli.

José de Ribera, known in Italian as Giuseppe de Ribera or Lo Spagnoletto (the little Spaniard), has imaged a sort of modern and secular transmogrification. Unlike those moments when, seated uncomfortably in a cathedral, one takes the blood of Christ between the lips and feels the texture of his flesh between the teeth, there is only the most vexed sense of antiquity in this painting. It may repeat some essential truth, but it does so mechanically. There is no attempt to revivify some elemental presence. Instead what Ribera notes is the creation of new forms of human subjectivity, the self-reproducing automaton, the automatic. The seed of the husband does not spring fully formed from the crucible of the wife. The steady advance of the modern belies the need for patriarchal interposition. As with the (modern) slave, antique narratives of descent and primogeniture must be reconstructed in order to establish the ideological ground on which all modern subjectivity rests. It is in this sense that I nominate the child that Maddalena holds in her arms as the most truly beastly figure in the familial tableau that Ribera creates. Wrapped in red, its greedy lips pursed and ready to take its mother’s overripe breast, the child stands decidedly apart from its father. The old man’s darkness disappears in the pink, light-framed visage of his offspring. Facing the infant is the carcass of what appears to be a quail, suggesting that the production of this child was done in the presence of destruction, the literal death of the natural, the disavowal of the flesh.

Again following the extremely useful clues provided by Cedric Robinson, I would remind you that the so-called Spanish Golden Age (siglo del oro), the period from the fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries that witnessed both Columbus’s “discovery” of the Americas and the phenomenally productive practices of Ribera, El Greco, Velázquez, Cervantes, and de Vega, hardly represented a moment of stability within “Spanish” culture. On the contrary, the very notion of a Golden Age was based on the diminution and suppression of cultural complexity, at least so far as it worked to celebrate the Reconquista that culminated with the expulsion of Prince Boabdil from Granada, the last of the Muslim strongholds on the Iberian Peninsula. Still, this was hardly a moment in which an emergent Spanish people might take pride in the achievement of economic, political, or cultural independence. Instead, as Robinson reminds us, much of the newfound Iberian confidence and prosperity was based upon the often heavy-handed interventions of Genoese traders. There is, in fact, an extremely strange and shockingly effective sleight of hand that has allowed a once living man, Cristoforo Colombo, to be simultaneously transformed into the Spanish national hero Cristóbal Colón and the father of Anglo-American colonization, Christopher Columbus (Robinson, Black Marxism, 106–9).16

Without belaboring the point, I would submit that what is so disturbing about Maddalena Ventura, con su marido is the fact that it so ably demonstrates what one might call a sense of cultural/ideological dislocation underwriting the productions of Golden Age intellectuals like Ribera. Though born in Valencia, Ribera spent his apprenticeship in Rome and Naples, then part of the Spanish empire, eventually becoming deeply enmeshed in Neapolitan cultural and intellectual life. Tellingly, the celebrated artist would never return to live in his Iberian birthplace. Instead he remained in Italy, courting the patronage of the Spanish elite. He established his career at precisely that place where artistic production intersected with the exigencies of capital accumulation and the newly developed philosophical/ideological structures (humanism) that attended it. Though much of the criticism of Maddalena Ventura turns on either explication of Ribera’s style or consideration of the work’s gender politics (including the possibility of Maddalena’s hormonal imbalance), I prefer to maintain my focus on the question of how Ribera narrates dynamic procedures of both re-spatialization and re-corporealization, procedures that included not only the Reconquista, but also the (dis)establishment of a complex of “fixed” ethnic and national boundaries.

I ask now that you focus your attention on the blessed/benighted face of America, the very child whom I take Maddalena to be holding in her arms, the child whom she shields from the dark, disapproving visage of her European husband. In particular, I would note the fact that the Spanish Golden Age was also the age of Spanish Empire, an empire whose greatest treasures were quite decidedly American. After the unification of the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon with the marriage of the Catholic monarchs Isabella and Ferdinand, the newly established community of “Spaniards” set about both to Christianize the peninsula and to build upon recently acquired—or at least recently modernized—abilities at conquest and annexation. Columbus’s adventures of 1492 led to Spain’s domination of much of the Caribbean and even more impressively the usurpation of huge swaths of the Inca and Aztec Empires of North, South, and Central America. The development of the modern Spanish nation absolutely depended on the extraction of value in the form of natural resources and human labor taken from its many colonies, particularly those of the Americas. The gold of the Golden Age was mined on the “uncharted,” “unspoiled” side of the Atlantic by communities of Africans, aboriginals, and mestizos, slaves and free persons alike, who produced for Spain the wealth and leisure necessary to create artists and intellectuals on the order of a Velázquez or a Goya.

What I argue against, however, is the deeply embedded assumption that enslaved and colonized people offered nothing other than labor. I chafe at the idea that “physical” labor, the act of tilling a field, digging a mine, or suckling a child, is in fact less creative, less cerebral, less imaginative than the labor of painting a portrait or writing a sonnet. When I make the claim that Americans, including African Americans, were central to the production of Spain, I mean to suggest something much more provocative than simply the known fact that colonizers and enslavers successfully monetized the labor of black and brown bodies. Instead, to say that “Africa and America produced Spain” disrupts the clumsy ways even contemporary scholars continue to narrate world economic, social, and cultural history such that progress always flows from a magical, always already developed Europe to an inevitably and irredeemably underdeveloped periphery. At the same time, however, I suggest that the cultural apparatuses that produced the fledgling Spanish nation were structured in rather precise relation to the complex interplay of race, caste, class, language, and gender that remain quite obvious in the so-called New World.

These realities become starkly apparent when one turns toward the gem of the Spanish New World colonies, “New Spain,” a location that more or less corresponds to present-day Mexico. Entering into the Spanish orbit at the beginning of the sixteenth century, New Spain not only became the largest and most prosperous of the Spanish colonies, but also one of the most ethnically and racially diverse. African slaves were key players in the creation of Spanish wealth, so much so that their presence, alongside that of the colony’s aboriginal subjects, both deeply fascinated and intensely troubled the “white” elites of the peninsula. The importance of blacks and browns to the articulation of an emergent “white” and “Spanish” identity necessitated the deployment of modes of normalization and control that would allow for the continuation of the thin fiction of a (white) European Spain while nonetheless continuing—and accelerating—the practices of cultural and economic dispersal that stood at the center of the empire’s rapid economic and cultural development.

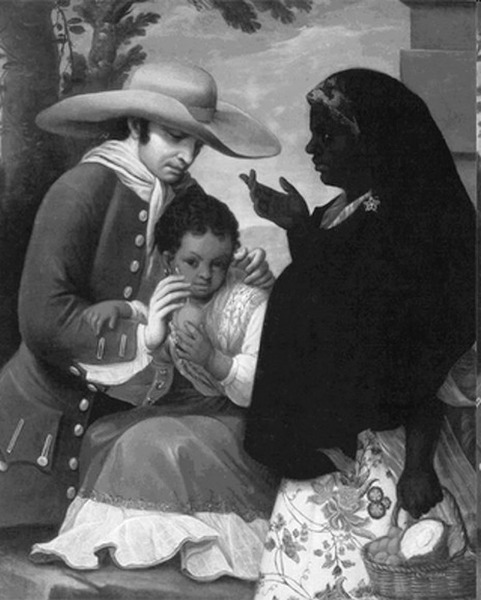

Among the most significant responses to this phenomenon were the hundreds of casta (caste) paintings that were produced in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century New Spain. Often extremely decorative and luxuriant, the paintings at once reproduced and extended the anxieties we saw on display in Ribera’s Maddalena Ventura, con su marido. The concern with production and reproduction is ever-present in the images. Father, mother, and child, light, dark, and mixed, are unendingly examined, giving voice to a developing/modernizing racialism (white and black produce mulatto; mestizo and Indian produce coyote; white and mulatto produce morisca) as well as the fascination with both the danger and vibrancy of Spanish colonialism.

Both a master of style and iconography and a self-conscious promoter of the interests of colonial artists, Miguel Cabrera (1695?–1768?) was easily one of the most accomplished of the casta artists in eighteenth-century New Spain.17 Cabrera assiduously struggled to rescript the distinction between colony and metropole, suggesting that the luxury, exuberance, and most especially the originality of New Spain were absolutely necessary for the production of an expansive and self-confident imperial culture. He evinced a surprisingly effective aesthetic naïveté, working throughout his career not to obscure but instead to make patently apparent the intimate connection between colonization and humanism. In a 1763 masterwork entitled De español y negra, mulata (From Spaniard and Black, Mulatta), Cabrera dresses the sobering frankness of racialist/colonialist ideology in a surprisingly sophisticated system of technical and iconographic practices (see figure I.2).

As with La mujer barbuda, the familial tableau is itself a study in the articulation of light and dark, life and death, birth and stillbirth. To the right of the painting a dark (African?) mother stands erect and aloof, maintaining contact with neither her “husband” nor her child. As she is dressed in a midnight-black shawl, her presumed racial distinction is made that much more obvious. She becomes, in fact, a sort of elemental personage, an ideograph. The flowered print of her skirt and the basket of ripe vegetables she carries in her left hand suggest an impersonal fecundity, an ability to give that is embedded less in her will than in her essence. With her right hand she gestures toward the downcast eyes of her child’s father. His handsome, immaculately drawn face and his large, light-colored hat rescue him from the emasculation and obscurity that we saw with Maddalena Ventura’s spouse, while shielding both himself and his child from the menacing threat of the mother’s imposing Africanity. At the same time, the hat’s large red ribbon reminds the viewer of both the blood that has been spilled in order to establish the luxuriant order of the painting and the revivification of masculine prerogative that the Spanish colonialist adventure in the Americas allows. The unchecked power of La mujer barbuda has been domesticated. The (American) child whom we find in the work of both Ribera and Cabrera leans heavily on the arm of her white father. Indeed, she is fashioned here as a delectable product, brightly dressed in red, white, blue, and gold. The tightly knotted severity of her mother’s hair has given way to an abundance of loose—or at least looser—curls. She will be both productive and reproductive. Though yet a girl, the fullness of a pubescent breast is suggested through the careful placement of what appears to be an orange held in her left hand, a gesture that rearticulates her African mother’s act of “freely” giving her fruits (child included) to the white colonialist. The primary action of the painting is the girl’s nonchalant offering of her bounty to her covetous father, his right ring finger almost on the verge of making contact with the plant’s ripe “nipple,” thereby reiterating his claim on his American crop.

I hope it is clear at this point that part of the reason that I have chosen to pair Spain and African America is that both cultural formations are easily recognized as sites of what one might think of as (cultural) promiscuity. I want, that is, to expand radically our understanding of the history of the protocols of race and space that underwrite—and determine—contemporary cultural studies. Stated in a more vulgar manner, the enslavement of millions of Africans produced a profoundly destabilizing cultural and linguistic leveling that reconstructed many distinct national and ethnic traditions as nothing more exotic than “the Black.” In the face of this reality, one can hardly criticize the many Africans and descendants of Africans who, when confronted by the panicked and shrill claim that Europeans and the descendants of Europeans somehow continue in their ancient specificities and stand above the hardscrabble facts of world history, counter that though Europe possesses a wealth of cultural diversity, it has been radically restructured by the racialist ideologies it worked so assiduously to create. I turn to Spain not only because it is patently obvious that the country’s claims to whiteness are so very thin, but also and more importantly because by attending to the history of Spanish (cultural) unification and expansion in relation to the history of Atlantic slavery and the development of a peculiar African American community, one imagines that we might eventually develop enough critical/ethical subtlety to free all of us from the unrelenting nightmares of racialism and white supremacy.

It is only recently that Spain and the Iberian Peninsula could easily be considered either European or white. Ever visible, Africa is less than ten miles away from the Spanish city of Tarifa. It is widely assumed, moreover, that the Iberians, the people who gave the peninsula its name, arrived from the “dark continent” around 1600 BC. They were followed later by “Asiatic” Phoenicians, hailing from present-day Lebanon, and Celts crossing the Pyrenees around 600 BC.18 What is certain is that Iberia developed specifically as a dynamic meeting point for traveling peoples coming from Africa, Asia, and Europe. Eventually Romans, “Germans,” Visigoths, and North African Arabs would cross either the Pyrenees or the Strait of Gibraltar in large numbers, adding to the cosmopolitan and multiethnic nature of the peninsula. Thus there has never been a singular Spanish people. Instead, nearly four thousand years of Iberian history has been marked by increasingly violent attempts to substitute abstract conceptions of white Western homogeneity and unity (Man) for the intense (human) complexity that the region and its various communities have always demonstrated.

Where this fact is most apparent is in the vexed relationship that Spaniards continue to have with the so-called Arab and Muslim world. By the eighth century AD, Arabs dominated much of the peninsula. Syrian-born Abd-al-Rahman I ruled most of Spain from his capital in present-day Córdoba until his death in 788, establishing close and mutually beneficial economic and cultural connections between Iberia, North Africa, and the Middle East (Pierson, History of Spain, 25–26). Moorish emirs subsequently used their considerable wealth and often massive armies to push relentlessly northward, eventually arriving as far as the city of Marseilles. All along the way, however, they were met by the hostile and resistant Christian kingdoms of Castile, Asturias, Aragon, Leon, Navarre, and Catalonia. Indeed, the centuries of war between the “Muslim” south and the “Christian” north provided much of the impetus for an often fragile and contentious process of unification as northern monarchs sought the aid of their Christian counterparts in their struggles against the Arabs. Not until January 2, 1492, were Ferdinand and Isabella able to drive Boabdil from Granada, where he sat enthroned among the handsome buildings and lush grounds of the breathtakingly beautiful Alhambra. Immediately thereafter, relentlessly thorough Isabella had the large community of practicing Jews expelled from Spain while allowing both Jewish—and eventually Muslim—converts, conversos and moriscos, to remain (Pierson, History of Spain, 51–52).

The story that is most well known—and obsessively repeated—about this grandest of the grand “Spanish” queens, however, is that in the very year that she presumably purged Spain of the last of its Muslims and Jews, she contracted with the Genoese adventurer Cristoforo Colombo to search for a direct ocean route to the Indian subcontinent, initiating the journey that resulted in the European “discovery” of the Americas. Under the leadership of Ferdinand and Isabella, Spaniards would become primary architects of what we now know as globalization, eventually colonizing not only much of the Americas, but also the Philippines and Guam. Of course the engine that drove this activity was Atlantic slavery. What most concerns me at this juncture, however, is the fact that though the conquests of Ferdinand and Isabella presumably solidified the peninsula’s Christian and “white” bona fides, they were nonetheless established on an unstable set of historical paradoxes that would have far-reaching implications for Spanish and Atlantic culture.

If one considers the major points of the brief history that I have just provided, it becomes possible to see a series of obvious cracks in the ideological structure of the Spanish national mythology. First, Ferdinand and Isabella were not the king and queen of Spain per se, but of Castile and Aragon, kingdoms that remained distinct until the couple’s marriage. Second, though the last of the “Moorish” kings was forced from the peninsula and into present-day Morocco, he nonetheless left behind scores of Muslims and Jews, those conversos and moriscos, whose conversions were so doubtful that the Inquisition was established—at least in part—in order to check the presumed prevarication and heresy that the royal couple suspected were constantly taking place in the very heart of the “Catholic” peninsula. Finally, while the discovery of America and the opening of trade with the Far East worked to establish Spain’s Golden Age, it also allowed for the constant movement of individuals, goods, and wealth onto, through, and out of the peninsula. Thus the apogee of Spanish wealth and culture was achieved at the very moment when the spatial, cultural, ethnic, and linguistic limits of the country seemed most porous and uncertain.

As Jeremy Lawrance has noted, after the sale of the first African slaves in Portugal in 1444, the Iberian Peninsula soon had one of the largest black populations in Europe, with an estimated 100,000 slaves living in what we now think of as Spain by the mid-sixteenth century. As early as the late fifteenth century, there were enough black freed persons in Seville, Barcelona, and Valencia to support confraternities.19 Moreover, by the time of the Seville census of 1565, blacks constituted more than 7 percent of the city’s population.20 The fact that in our contemporary discussions of Spain, particularly its unenviable location at the center of the global financial crisis that began in 2007 as well as the hysteria surrounding unwanted “foreign” migrants to Europe, there is so little consideration of the quite significant presence of Africans on the peninsula before and after 1492 is itself evidence of the remarkable structural—and ideological—work that was performed during the Reconquista. The expulsion of Muslims and Jews from the peninsula, the denial of the fleshy truth of the necessary/inevitable/enviable mixing of Christian, Muslim, Jew, African, and European, was never simply a martial exercise but also a largely successful attempt to erase knowledge of the long and extremely complex history of Spain’s intimate connection to Africa and Africans and to substitute a tinny conception of so-called white and European identity, an identity that would prove invaluable as Spaniards pursued the conquest and colonization of huge swaths of the planet.21

* * *

As will become increasingly obvious as you travel through Archives of Flesh, my efforts to bring together the variety of texts, contexts, and methods that structure this work are facilitated by a number of reasonably well considered guesses. One of the most clearly defined of these builds upon the fact that the United States became a self-consciously imperial power after divesting Spain of the last of its most significant colonies during the 1898 Spanish-American War. Moreover, even as Spanish culture was disrupted after the country’s quick defeat at the hands of the Americans, many Spanish intellectuals, including Federico García Lorca, believed that the changes the war brought might “rescue” the country from its “stifling” traditionalism. Meanwhile, African Americans took great pride in the fact that black soldiers played a decisive role in the conflict. More important still, African American intellectuals, especially Du Bois, Robeson, Hughes, Himes, Wright, and Larsen, recognized in Spain a country whose “awkward” relationship to Europe resembled their own relationships with America. Black intellectuals continued to remain deeply interested in Spain from 1898 through the Spanish Civil War and on through the years of the Franco regime. Robeson, Hughes, Larsen, Himes, and Wright traveled there. Himes, Wright, and Hughes wrote extensively about their experiences. Meanwhile, many other African American artists ranging from Romare Bearden and Miles Davis to Lynn Nottage and Bob Kaufman have utilized “Spanish themes” in their works. For Spaniards, African American culture represented both the promise and the danger of modernity. Lorca treated black life in Harlem with pronounced concern in his posthumously published collection Poeta en Nueva York (Poet in New York), largely a chronicle of his 1929–1930 visit to the United States and Cuba. Moreover, Picasso’s interest in African or “tribal” sculpture was filtered through a pan-Africanist sensibility that owes a great deal to African American intellectuals and intellectual practices.

Still, I hope not simply to retrace the demonstrably broad and deep connections between African Americans and Spaniards. This book is ultimately an effort to transgress and erase the imagined boundaries that continue to demarcate not only the African, the European, and the American, but more important still, the Man, the human, and the animal. I will attempt throughout to make sense of the continual reappearance of Spain in the African American intellectual archive by filtering my awareness of this reality through an understanding of the long struggle by black individuals and communities against the lack of full consideration of black life within humanism’s main precincts. I have less desire to name something like a “black Spain” than I do to use the African American consideration of Spain and the Hispanic as a powerful heuristic. In the hands of the intellectuals whom we will examine in this book, Spain becomes a particularly creative means by which to deliver us all from the choking hold of the racialist, anti-black conceits that structure so much of humanistic inquiry.

In the pages that follow, I will produce a theoretical, historical, and aesthetic treatment of the relation between space, race, ethnicity, humanity, and animality in the works of Langston Hughes, Richard Wright, Chester Himes, Federico García Lorca, Nella Larsen, Lynn Nottage, and Pablo Picasso. As I hope is obvious by now, I will attempt throughout to pay close attention to the ways that slavery, colonization, and military conflict have contributed to the aesthetic practices of American and Spanish intellectuals. Beginning with a treatment of the intimate interrelations between gender, aesthetics, and war making, particularly as these are demonstrated in the participation of African American troops in the Spanish-American War and the Spanish Civil War, I argue that even in the progressive archival practices that attend the memorialization of leftist militancy, we see a stunningly naïve reiteration of the necessity of the “little person,” the oppressed—and compressed—human form, within our most cherished procedures of history making and asetheticization. Working in a similar vein, I will strive in the next two chapters to demonstrate how Federico García Lorca and Langston Hughes continued to resist the leveling that is so much a part of the structure of modernity. In Hughes’s case, he plays with the matter of light and dark in order to imagine forms of human subjectivity that are not wholly structured by capitalism and white supremacy, in order, that is, to name a subjectivity in which the flesh is not always already rejected. In the process, he returns repeatedly to the figure of the prostitute. Indeed, Hughes utilizes images of women and girls selling sex in order to demonstrate the complex relation of mind to body that so vexes modern intellectuals. Similarly, Lorca’s fascination with so-called duende, or soul, and the low individuals whom he takes to most represent it (Gypsies, women, and homosexuals) grows out of an awareness that the structures and practices of modernity tend at once to extend and obscure individuality. Thus Lorca is truly equivocal when confronted with “two Spains,” one modern, the other traditional. He is both celebratory and fretful in the face of a comforting yet stifling Andalusian domesticity. At the same time, he both courts and rejects the freedom and seeming fungibility of the traveling gypsy and the urban homosexual.

I then examine Chester Himes’s and Richard Wright’s vexed relationships to Spain, narrating their attempts finally to rationalize Western humanism’s many contradictions as they make their peripatetic marches through the peninsula in search of the primitivism and paganism that they assume pervades the whole of Spanish life. In the process, they at once criticize and ratify the very processes of abstraction and compression that so much within the practice of Atlantic slavery was meant to enforce. Indeed, both Himes and Wright make bitter retreats from what they take to be a benighted Spain, treating the country as a sort of ugly, inconvenient memory, a scar capable of reminding the modern black intellectual of a dark, distant, and embarrassing past. Yet in both cases they attempt to extract some form of redemption from the country’s marginality, to discern on Spanish ground alternatives to the worst aspects of white supremacy and anti-human violence.

I end with a conclusion in which I read Pablo Picasso’s 1937 masterpiece Guernica and his fifty-eight-work 1957 series Las meninas (named in honor or Velázquez’s 1656 portrait of the Infanta Margarita Teresa) against contemporary American playwright Lynn Nottage’s tragicomic play of race, desire, and intrigue in the court of Louis XIV, also named Las Meninas. Paying careful attention to the economy of repetition that each artist deploys as they rearticulate—and de-articulate—codes of representation made plain by Velázquez, I use my examination of the multiple intertextualities binding Picasso and Nottage in order to argue that the necessary task of reconsidering the conceptual structures of Western humanism might easily devolve into metaphysics if we cannot integrate our understanding of radical disruptions in the history of philosophy with our awareness of similarly radical disruptions in politics and economics. Examining Nottage’s relentlessly historicist play alongside Picasso’s masterworks, we come to understand that the codes of modern representation cannot be broadly understood in the absence of sustained consideration of the effect of slavery and colonization on even and especially the most central, most celebrated locations in elite European and American culture.