The OB West staff proposed that Heeresgruppe G be assigned a supporting role in the Ardennes offensive, consisting of a strike towards Metz, but both Hitler and Rundstedt quickly dismissed this idea as preposterous given the army group’s meager resources. In November 1944, Heeresgruppe G was informed that a major offensive in the west would take place sometime in the immediate future, but was not informed of the date, location, or other details. On December 15, the Heeresgruppe G headquarters opened sealed orders that explained that the offensive would take place in the Ardennes the following day, but few details were provided. Berlin expected that the Ardennes offensive would create a lull in Alsace and so under such circumstances, Heeresgruppe G should plan and conduct a local offensive to further relieve pressure from the Ardennes offensive. The date and objective of the offensive were left up to the local command, but the plan had to be approved by Hitler.

When the Seventh US Army front went dormant on December 19/20, this gave Heeresgruppe G the cue to begin an offensive. The first step was to pull back the 21. Panzer-Division and 25. Panzergrenadier-Division for refitting, since they would be needed as the army group’s mobile reserve. Two potential operations were considered. The first option was an attack out of the “Orscholz switch” area southwest of Trier against the overextended remainder of Patton’s Third Army, XX Corps. This operation was on the northern fringe of the army group’s forces and would require extensive regrouping of forces, which would be vulnerable to US air power, so this plan was rejected. The second option was a strike through the Low Vosges to recapture the Saverne Gap with the objective of re-establishing contact with AOK 19 in the Colmar Pocket. On December 23, Berlin approved the Saverne option. The only major reinforcement offered for the attack was 6. SS-Gebirgsdivision “Nord,” which was being transferred from Finland and which was expected to arrive between Christmas and New Year; the bulk of the forces for the offensive would have to come from those already available since all theater reserves were committed to the Ardennes fighting. There was also a promise that Himmler’s Heeresgruppe Oberrhein would stage its own attack against the Alsace bridgehead, although the Heeresgruppe G staff was not convinced that AOK 19 had the forces necessary to conduct any sort of offensive action in view of the desperate situation in the Colmar Pocket.

The Festung Kommandant Oberrhein constructed several defensive lines in Alsace starting in September 1944 with two lines in the Vosges Mountains and several shorter lines on the Rhine Plain. The Germans absorbed some of the older French defenses into their own defense lines around Colmar, such as this machine-gun pillbox. (NARA)

The plan was refined during the final week of December before receiving Hitler’s final approval. The three potential avenues of attack were to the west of the Low Vosges along the Saar River, through the Low Vosges south of Bitche, or to the east of the Vosges on the Alsatian plains via Wissembourg. The western avenue was the best for rapid movement since the road network would support mechanized forces and the Saar River could serve as a defensive shield. On the other hand, this was the center of gravity for the US XV Corps and the open terrain would make the attack vulnerable to US air attack if the weather was favorable. The center approach offered good assembly areas for German infantry, and Heeresgruppe G still held the concentration of Maginot Line forts around Bitche. In addition, the forested and mountainous terrain would mask the German attack and make US air attack difficult. On the other hand, the mountainous terrain of the Low Vosges had poor roads and could not easily support Panzer forces in bad winter weather. The eastern avenue had a good road network and relatively weak American forces. On the other hand, on this front the terrain was well suited to defense, the US Army controlled several Maginot forts in the area and had extensively mined the sector, and the layout of the rivers and the presence of the Hagenau forest presented significant terrain obstructions. As a result of these considerations, Heeresgruppe G selected the center route through the Low Vosges from Bitche and this was approved by Blaskowitz and Rundstedt on December 24; it received the codename Nordwind (north wind) at this time.

Hitler’s attitudes towards the plan were more critical, based on the lessons of the recent Ardennes offensive. The initial infantry penetrations had gone badly and the premature commitment of Panzers (especially in the 6. Panzerarmee sector) had led to heavy tank losses and a stalled attack. As a result, Hitler doubted that the Heeresgruppe G plan would succeed and in particular he was skeptical that the infantry would do well in the forested mountains in winter conditions, so he favored the western avenue in more open terrain. In the end, a compromise was reached with Rundstedt and Blaskowitz. The western approach, labeled “Sturmgruppe 1,” became an area of advance together with the center approach, now dubbed “Sturmgruppe 2.” Hitler was also insistent that neither Panzer division be committed, not even parts of the divisions, until a breakthrough had been made. In view of the terrain, he directed that the remaining armor support, consisting of about 90 assault guns and tank destroyers, be provided to the 17. SS-Panzergrenadier-Division which would form the core of the western thrust. Hitler selected the night of December 31 to January 1 for the attack on the presumption that New Year’s Eve would be celebrated behind American lines. A planned diversionary attack from the Orscholz switch against Patton’s XX Corps was limited to a divisional feint because of a lack of forces.

After the Ardennes failure, Hitler had become convinced that massive offensives at army group level were no longer feasible in the west, and that a better option would be to stage smaller, sequential offensives at field army or corps level, and to exploit any of these when they showed promise. As a result, he made it clear to Rundstedt and Blaskowitz that Nordwind was only the first stage of a sequence of Alsace attacks. There would be further attacks by Himmler’s Oberrhein command, and a follow-up offensive codenamed Zahnarzt (dentist) would take place when Nordwind was complete.

The Heeresgruppe G staff was not pleased with the changes, though they were prudent enough not to complain directly to Hitler or to the recently arrived Blaskowitz, who had been present when the final decisions were made. Their main concern was that Hitler’s version of the plan had two centers of gravity, which would disperse the force of the effort and was against doctrine. The forces available were hardly capable of a single main thrust, and removing armored support from the center thrust would further weaken its chances.

The plan presumed that surprise would be absolutely essential to the success of the operation, so strict security measures were established. Access to details of the plan was restricted to corps and divisional commanders as well as their staffs and some selected officers; no information was to be passed by radio or telephone, only through written communications. No major troop movements were permitted until the night of December 29/30 for fear of disclosing the plans, providing only a day to mass the forces. Reconnaissance missions were prohibited except for normal patrol activities. No preliminary artillery bombardment was allowed, as experience of the Ardennes fighting showed that the artillery preparation had simply alerted forward US units without causing significant casualties.

Heeresgruppe G hoped to activate a supporting operation by Himmler’s neighboring Oberrhein command, but since AOK 19 had been taken from their control in early December, they had no power to coordinate such plans. Hitler’s version of the Nordwind plan also included a supporting Heeresgruppe Oberrhein operation. The objective of this attack was to establish bridgeheads on either side of Strasbourg as a preliminary step to recapturing the city. There have been hints that Himmler deliberately interfered with attempts to coordinate the attacks as part of an effort to disentangle the two efforts so that his command could take the credit when Strasbourg was recaptured. In the event, the plan to start the Heeresgruppe Oberrhein attack 48 hours after Nordwind was changed on December 27 when a specific date was dropped in favor of initiating the attack after Heeresgruppe G committed its Panzer exploitation force.

On December 19, Eisenhower held a meeting at Verdun with all senior US commanders to plan a response to the Ardennes offensive. Patton offered to shift one corps immediately to relieve Bastogne, followed by a second within a few days’ time. After Eisenhower concurred, Devers was instructed that the 6th Army Group would have to halt all offensive operations and that Patch’s Seventh Army would have to cover part of Patton’s former front line. During follow-up discussions on December 26, Eisenhower told Devers that he wanted him to pull VI Corps back from the Rhine and to straighten out his extended line by withdrawing to the Vosges Mountains. Devers pointed out that both his staff and Patch’s headquarters did not expect the main German attack to come against VI Corps due to the nature of the terrain and the Maginot forts, but instead against XV Corps along the Saar River. Devers left with the impression that there was no urgency to the withdrawal and he instructed Patch to plan three phased withdrawals of VI Corps in the event of a heavy attack, but only if an attack developed. Whilst SHAEF continued to press for a withdrawal, Devers and Patch were not willing to give up defensible positions simply because of SHAEF’s skittish assessment of the threat after the Ardennes intelligence fiasco. This argument would eventually come to a head, but only after the Wehrmacht launched Nordwind.

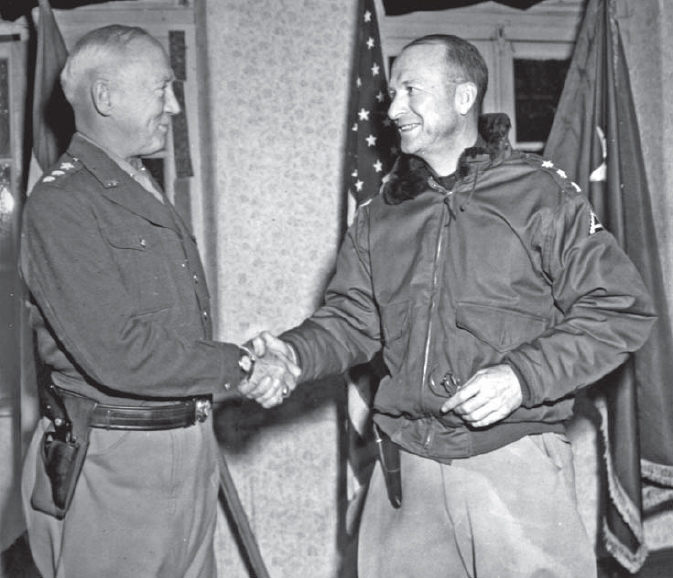

Patch’s Seventh US Army was frequently called upon to support Patton’s Third Army to the north. When Third Army was sent to relieve Bastogne in late December 1944, Patch was instructed to take over Patton’s sector. This is Patton and Patch at Seventh Army headquarters in Sarrebourg on December 4, 1944. (NARA)

Although there have long been stories that the Allies learned of Operation Nordwind by Ultra signals intelligence, official histories of the intelligence effort have categorically denied that any such messages were intercepted. As mentioned above, the Wehrmacht had strict instructions that no messages related to Nordwind were to be passed by radio, so any intelligence gathered by signals intercepts would have simply been inferences made from traffic patterns. Around Christmas, the Seventh Army G-2 officer, Colonel William Quinn, concluded from suspicious German activity that an attack was likely. For example, aerial photo reconnaissance in the Bitche area around Christmas had shown that the Germans had prepared forward artillery positions that were not yet occupied, and patrols sent to collect prisoners for interrogation were running into unusually strong German forces. Although Ultra did not provide any specific evidence of the attack, the shifting order of battle also suggested an attack was imminent. Quinn briefed Patch about his suspicions, and when Quinn suggested the attack would come on New Year’s Eve, Patch asked why. Quinn replied: “German stupidity: they know we are New Year’s Eve addicts and will all be drunk and this will be the finest time for a penetration.” Patch agreed with the assessment and convinced Devers of the threat.

Patch and the Seventh Army staff was convinced that the most dangerous avenue of a German attack, and the most likely, was the western approach down the Saar River. The Germans had already attempted to use this avenue in mid-December when they had launched a spoiling attack with Panzer-Lehr-Division. Although they recognized that a more direct thrust through the Low Vosges was a possibility, the Seventh Army viewed the terrain as far less trafficable, especially since the onset of hard winter weather in late December. They were not at all convinced that a major attack would be launched along the Alsatian plains around Lauterbourg, as US troops held chunks of the Maginot Line and had established significant defenses in the sector already.

Their superiors at SHAEF were insistent that Seventh Army divert adequate reserves to handle the anticipated assault. Devers gave this task to the 12th Armored Division and the 36th Division. In addition, the French 2e Division Blindée (which had garrisoned Strasbourg) was brought nearer to the Low Vosges as a potential counterattack force. On New Year’s Eve, Patch met his two corps commanders and warned them to expect an attack within 24 hours; all holiday festivities would be postponed. On the afternoon of December 31, aerial reconnaissance reported that German troop movements had started all along the front. But as snow clouds gathered, further reconnaissance was curtailed and there was no precise information on the focus of the German actions.